Shenandoah National Park

| Shenandoah National Park | |

|---|---|

| IUCN Category II (National Park) | |

| | |

| Location: | Virginia, USA |

| Nearest city: | Waynesboro |

| Area: | 199,017 acres (805 km²) |

| Established: | December 26, 1935 |

| Visitation: | 1,076,150 (in 2006) |

| Governing body: | National Park Service |

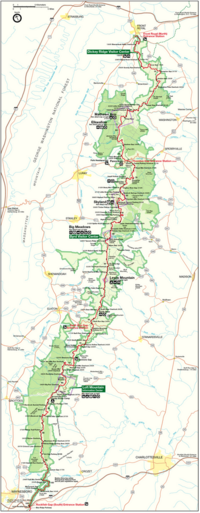

Shenandoah National Park is a beautiful historic national treasure that covers the crest of the Blue Ridge Mountains for more than 75 miles in the northern part of the U.S. state of Virginia. A preserve of 311 square miles (805 square km), this national park, known for its inspiring panoramic views, is long and narrow, with the broad Shenandoah River and valley on the west side, and the rolling hills of the Virginia Piedmont on the east. Almost 40 percent of the land area (79,579 acres/322 km²) has been designated as Wilderness and is protected as part of the National Wilderness Preservation System. The park attracts more than 2 million visitors a year and has 500 miles of hiking trails including 45 miles of the popular Appalachian Trail. The highest peak is Hawksbill Mountain at 4,051 feet (1,235 m). The name âShenandoahâ is a Native American word meaning âDaughter of the Stars.â

Geography

Authorized in 1926 and established in 1935, Shenandoah National Park is a preserve of 311 square miles (805 square km) in the northern Virginia Blue Ridge section of the Appalachian Mountains. The famous Skyline Drive, which runs north to south for the length of the park, is known for some of the most fantastic views in the eastern U.S. and is a common getâaway for an afternoon drive, especially in the autumn.

The park is divided into three sections; (northern) from Front Royal to Thornton Gap, (central) from Thornton Gap to Swift Run Gap, and (southern) from Swift Run Gap to Rockfish Gap. Each of these sections is divided by a highway. South of Rockfish Gap, Skyline Drive meets the Blue Ridge Parkway, which is part of the Appalachian Mountains and runs to the Smoky Mountain National Park.

Flora and Fauna

There are four distinct seasons in the park making it an exciting place to visit any time of the year. The area is best known for its rich red foliage that begins in September and peaks in mid- to late October. Spring brings an abundance of wildflowers in April, while the leaves on the trees come out in May.

On southwestern faces of some of the southernmost hillsides, pine predominates and there is the occasional prickly pear cactus, which grows naturally. In contrast, some of the northeastern aspects are most likely to have small but dense stands of moisture-loving hemlocks and mosses in abundance. Other commonly found plants include oak, hickory, chestnut, maple, tulip poplar, mountain laurel, milkweed, daisies, jack-in-the-pulpits, lady slipper orchids, rose azaleas, and many species of ferns.

The once predominant American Chestnut tree was effectively brought to extinction in the Park by a fungus known as the Chestnut blight during the 1930s â though the tree continues to grow in the park, it does not reach maturity and dies back before it can reproduce. Various species of oaks superseded the chestnuts and became the dominant tree species. Gypsy moth infestations beginning in the early 1990s began to erode the dominance of the oak forests as the moths would primarily consume their leaves. Though the moths are not as prevelant as they once were, they continue to affect the forest and have destroyed almost 10 percent of the oak groves.

- Mammals include Whitetailed deer, black bear, bobcat, raccoon, skunk, opossum, groundhog, gray fox, gray squirrel, and eastern cottontail rabbit. There are beliived to be mountain lions in remote areas of the park.

- Over 200 species of birds make their home in the park for at least part of the year. About 30 live in the park year-round, including barred owls, Carolina chickadees, Red-tailed Hawks, and wild turkeys. The Peregrine Falcon was reintroduced into the park in the mid 1990s and by the end of the twentieth century numerous nesting pairs had formed.

- Thirty-two species of fish have been documented in the park, including brook trout, longnose and blacknose dance, and the bluehead chub.

Seventy-four rare species and community types have been recorded in the park. According to the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation âThe significant number of natural heritage resources in Shenandoah National Park is testimony to its rich biodiversity. The parkâs large area, range of elevations, varied topography, and assemblage of substrates provide diverse conditions suitable for more rare species and significant natural communities than any other Mid-Atlantic Region national park unit.â A few of the rare species recorded are the Shenandoah Salamander, birds such as the Winter Wren and Blackburnian Warbler, and plants and trees such as Blue Flag Iris, Speckled Alder, and the Leathery Grape-Fern.

Climate

The climate of Shenandoah National Park is typical eastern mid-Atlantic woodland and only the highest points of the mountains show much change or alteration of typical flora and fauna species as might be found at sea level. The park has an average annual rainfall of 39 inches with thunderstorms that occur throughout the year. The winter snowfall is fairly modest with an average of 29 inches per year. Summer is the most popular time to visit the park with pleasant temperatures (Fahrenheit) averaging from the mid-40s to high 50s at night and low 70s to mid-80s during the day. It is usually 10 degrees warmer in the valley than in the mountain areas of the park.

Geology

Geologists believe the mountains that make up the Shenandoah National Park to be more than 1 billion years oldâsome of the most ancient in the world. Due to the forces of wind, water, frost, and ice for millions of years, the mountains have been worn away to a top elevation of 4,051 feet (1,235 m). These same forces continue to sculpt and define the breathtaking scenery of the Shenandoah National Park today. Visitors of the park can see the granite component of this ancient rock at Old Rag Mountain and Maryâs Rock Tunnel. Other rock types that can be seen in the park include basalts, made from lava flows, and sedimentary rocks such as sandstone, quartzite, and phyllite.

History

Around 8,000-9,000 years ago, the first traces of humans were recorded on the land that would become the park. Native Americans made their homes there for centuries, living the lifestyle of hunter-gatherers.

In the early 1700s, Europeans came to the area as hunters and trappers. By 1750, the first settlers moved into the lower hollows near springs and streams, and began cultivating the land for farming and grazing. Before long the mining of iron, copper, and manganese began.

The state of Virginia slowly began acquiring the land from landowners, according to eminent domain laws, in order to transfer it to the U.S. Governmentâwith the provision it would be designated a National Park. On May 22, 1926, President Coolidge signed into law a bill authorizing the creation of Shenandoah National Park. However, it wasnât until December 26, 1935, nearly 10 years later, that the federal government officially accepted title to the land and the park was fully established.

During that time, the Summer White House was established by President Hoover on the Rapidan River. The construction of Skyline Drive began and the Civilian Conservation Corps was established and began work in the park area.

In the creation of the park and Skyline Drive, over 500 families and entire communities were forced to relocate. However, the development of the park and the construction of Skyline Drive created badly needed jobs for many Virginians during the Great Depression. At that time, nearly 90 percent of the inhabitants worked the land for a living, many in the apple orchards in the valley and in areas near the eastern slopes. A 1930 drought destroyed the crops of many families in the area. The work to create the National Park and Skyline Drive began following this drought.

Since 1977, nearly half of the Green Springs National Historic Landmark District, a nearby area affiliated with Shenandoah National Park, has been protected by preservation easements held by the National Park Service.

Attractions

Waterfalls

|

The park is best known for Skyline Drive, a 105 mile (169 km) road that runs the entire length of the park along the ridge of the mountains connecting at the south end with the 469 mile (755 km) Blue Ridge Parkway. The drive is particularly popular in the autumn when the leaves are changing colors. Also in the park are 101 miles (162 km) of the Appalachian Trail. In total, there are over 500 miles (800 km) of trails within the park. Of the trails, one of the most popular is Old Rag Mountain, which offers a thrilling rock scramble and some of the most breathtaking views in Virginia. There is also horseback riding, camping, bicycling, and spectacular waterfalls. The Skyline Drive is designated as a National Scenic Byway.

Stony Man Trail

This is one of the most scenic trails in the Skyline drive. It ends at a cliff and offers a beautiful overlook.

Dark Hollow Falls Trail

Dark Hollow Falls is another scenic trail of Skyline Drive and ends in waterfalls. The trail is at the edge of a stream, which enhances the enjoyment. Birds, butterflies, deer, and occasionally black bear and timber rattlesnake may be seen on this hike, but have not been known to harm any visitors.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Away.com. Shenandoah National Park Retrieved November 20, 2007.

- Blackley, Pat, and Chuck Blackley. 2003. Shenandoah National Park impressions. Helena, MT: Farcounty Press. ISBN 1560372303 and ISBN 9781560372301

- Butcher, Russell D., and Lynn P. Whitaker. 1999. Guide to national parks. Northeast region. NPCA national park guide series. Guilford, Conn: Globe Pequot Press. ISBN 0762705728 and ISBN 9780762705726

- Manning, Russ, and Russ Manning. 2000. 75 hikes in Virginia's Shenandoah National Park. Seattle, WA: Mountaineers. ISBN 0898866359 and ISBN 9780898866353

- Radlauer, Ruth, Ed Radlauer, and Rolf Zillmer. 1982. Shenandoah National Park. Parks for people. Chicago: Childrens Press. ISBN 0516077449 and ISBN 9780516077444

- Shelton, Napier. 1975. The nature of Shenandoah: a naturalist's story of a mountain park. [Harpers Ferry, W. Va.]: Office of Publications, National Park Service, U.S. Dept. of the Interior.

- Uhler, John William. Seasons of Shenandoah National Park Page Makers, LLC.

External links

All links retrieved January 27, 2023.

| National parks of the United States | |

|---|---|

| Acadia ⢠American Samoa ⢠Arches ⢠Badlands ⢠Big Bend ⢠Biscayne ⢠Black Canyon of the Gunnison ⢠Bryce Canyon ⢠Canyonlands ⢠Capitol Reef ⢠Carlsbad Caverns ⢠Channel Islands ⢠Congaree ⢠Crater Lake ⢠Cuyahoga Valley ⢠Death Valley ⢠Denali ⢠Dry Tortugas ⢠Everglades ⢠Gates of the Arctic ⢠Glacier ⢠Glacier Bay ⢠Grand Canyon ⢠Grand Teton ⢠Great Basin ⢠Great Sand Dunes ⢠Great Smoky Mountains ⢠Guadalupe Mountains ⢠Haleakala ⢠Hawaii Volcanoes ⢠Hot Springs ⢠Isle Royale ⢠Joshua Tree ⢠Katmai ⢠Kenai Fjords ⢠Kings Canyon ⢠Kobuk Valley ⢠Lake Clark ⢠Lassen Volcanic ⢠Mammoth Cave ⢠Mesa Verde ⢠Mount Rainier ⢠North Cascades ⢠Olympic ⢠Petrified Forest ⢠Redwood ⢠Rocky Mountain ⢠Saguaro ⢠Sequoia ⢠Shenandoah ⢠Theodore Roosevelt ⢠Virgin Islands ⢠Voyageurs ⢠Wind Cave ⢠Wrangell-St. Elias ⢠Yellowstone ⢠Yosemite ⢠Zion List by: date established, state |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.