Ahab

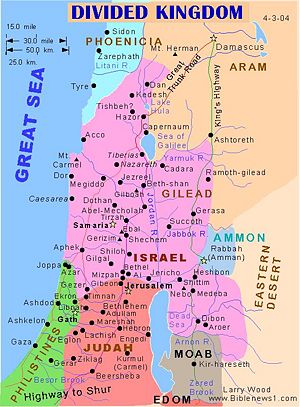

Ahab or Ach'av (×Öˇ×Ö°×Ö¸×, "Brother of the father") was an important king of Israel. The son and successor of King Omri, his reign is dated variously, with estimates ranging from 869-850 B.C.E. to 874-853 B.C.E.

Ahab was the first of the northern kings to establish a stable government. He solidified a period of peace with Judah and created a small empire by exacting tribute from the kingdom of Moab. He was a great builder, and apparently maintained the most significant force of charioteers in the entire region. His kingdom was prosperous, literate, and strong. He also forced trade concessions from the powerful Syrian king Ben-Hadad after defeating him in battle and contributed significantly to a coalition effort to resist the onslaught of the newly emergent Assyrian empire.

The biblical writers are harshly critical of Ahab for supporting Baal worship alongside of the worship of the Israelite God Yahweh, and for marrying the Phoenician princess Jezebel of Tyre. This alliance was apparently very successful financially, but brought the wrath of certain Israelite prophets, especially Elijah. Ahab's daughter, Athaliah, was married to King Jehoram of Judah and later ruled that nation for seven years as queen. The Bible portrays Ahab as one of the most evil of the kings of Israel.

Biblical account

Ahab's father, Omri established a powerful dynasty and made Israel into a major regional power. He built an impressive new capital, the strategically located town of Samaria in central Palestine, increasing his control of overland trade and providing good access to the Mediterranean. He ended a fratricidal war with the southern Kingdom of Judah and established a friendship with the Phoenician power of Tyre. Omri sealed this alliance by fatefully marrying Ahab, his heir, to the Tyrian princess Jezebel.

Ahab and Elijah

The biblical attitude toward Ahab focuses a good deal of its attention on the influence of his wife, Jezebel, both in his toleration of Baal worship and allowing her to persecute those of the Yahwist prophets who opposed the royal policies. Yet, the marriage of Ahab and Jezebel originally may have portended something very different to the psalmist who penned the following verses, thought by some scholars to be a hymn composed in honor Jezebel's arrival in Samaria to marry Ahab:

- Listen, O daughter, consider and give ear:

- Forget your people and your father's house...

- The Daughter of Tyre will come with a gift,

- men of wealth will seek your favor.

- All glorious is the princess within her chamber;

- her gown is interwoven with gold. (Psalm 45:10-13)

By the time recounted in 1 Kings 17-20, it is clear that Jezebel had forgotten neither her home nor her Phoenician religion. Instead, she has favored the worship of Baal Melqart, the patron deity of Tyre. As a result, Ahab is confronted by the prophet Elijah, who predicts that there will be no rain in Ahab's kingdom except by his prophetic word (Baal was thought by the Canaanites to be a god of rain and fertility).

A severe drought follows, and after three years, a desperate Ahab sends an expedition in search of pasture land for his horses, who face death from lack of water. His palace steward, Obadiah, encounters Elijah, and sets up a meeting between him and Ahab. Seeing Elijah as responsible for the lack of rain, Ahab declares: "Is that you, you troubler of Israel?" (1 Kings 18:17) Elijah, however, places the blame for the drought squarely on Ahab and Omri for "serving the Baals."

Elijah tells Ahab to invite the prophets of Baal and Ashera to meet him for a spiritual show-down on Mount Carmel. He alleges that the 450 prophets of Baal and four hundred prophets of Ashera have received state support due to Jezebel's influence, while many of the prophets of Yahweh have been killed or forced into hiding.

Ahab facilitates Elijah's request. After Elijah's dramatic victory on Carmel, Ahab stands by as Elijah orders 450 of the prophets of Baal slain in the valley below. Elijah then prophesies that the rain will now return to Israel, which it promptly does, in accordance with his prayers (1 Kings 18). Jezebel, hearing Ahab's report of the events, threatens Elijah with death, and the prophet flees to the far south in Judah.

Victory over Ben-Hadad

The narrative now turns back to secular affairs. Ahab faces a severe threat from a powerful coalitionâthe Bible speaks of "32 kings"âof Syrian forces and their allies under Ben-Hadad. An unnamed prophet of Yahweh declares that God will give victory to Ahab. The Israelite army gains the upper hand as predicted, and Yahweh's prophet counsels Ahab to prepare for another battle the following spring. The two sides then muster near Aphek, where the forces of Israel again inflict heavy casualties on the Syrians and later breach the walls of Aphek when Ben-Hadad retreats there.

Ben-Hadad sues for peace, agreeing to return all of the cities taken from Israel under Omri's reign and also allowing Ahab favorable trading rights in Damascus. However, another prophet of Yahweh condemns Ahab for allowing Ben-Hadad to live, declaring Ahab himself will die as a result (1 Kings 20:42).

Naboth's Vineyard

Ahab gets into more trouble with the prophets over his plan to buy a vineyard from a man called Naboth the Jezreelite. Naboth refuses to sell, and Jezebel hatches a diabolical plan to obtain the land by framing Naboth as a traitor and blasphemer. The plan succeeds, and the innocent Naboth dies by stoning. Ahab then seizes the vineyard as his own. God immediately commands Elijah to return to the north to condemn Ahab for his wickedness. The prophet's channeled warning from Yahweh is dire:

- 'I will consume your descendants and cut off from Ahab every last male in Israelâslave or free'... And also concerning Jezebel the Lord says: 'Dogs will devour Jezebel by the wall of Jezreel.' (1 Kings 21:21-23)

Ahab repents with fasting and sackcloth, clearly humbled, and Yahweh changes his mind, deciding to exact vengeance not on Ahab himself, but upon his son.

Micaiah's prophecy

The little-known prophet Micaiah son of Imlah now makes his only biblical appearance, but it is a particularly intriguing one. Jehoshaphat, the king of Judah, comes to Ahab's capital of Samaria on a state visit. Ahab asks his support to retake the town of Ramoth Gilead from the Syrians. Jehoshaphat requests the counsel of Yahweh before agreeing, and one hundred prophets are enlisted to inquire of Him. "Yahweh will give it into the king's hand," they unanimously declare. Jehoshaphat, however, requests one more opinion, and Ahab sends for the cantankerous Micaiah, saying: "There is still one man through whom we can inquire of the Lord, but I hate him because he never prophesies anything good about me, but always bad."

Micaiah arrives and, surprisingly, confirms what the other prophets have said. However, pressed by Ahab, he changes his testimony, saying: "I saw all Israel scattered on the hills like sheep without a shepherd."

Micaiah then reports a vision explaining why the other prophets issued a false prognosis: Yahweh has intentionally sent a "lying spirit" among them, because He wants Ahab to attack the Syrians and be defeated (1 Kings 22:22).

The Battle of Ramoth Gilead

Jehoshaphat and Ahab decide to take the advice of the majority of the prophets and go out together to the battle. Ahab disguises himself as a common soldier, but Jehoshaphat dresses in royal splendor. By chance, Ahab is struck by an archer, despite his disguise. He withdraws from the battle and dies later from loss of blood. His burial takes place with honor in the capital, but the narrator informs us that dogs do lick up the royal blood as it is washed from his chariot. The story of Ahab concludes:

- As for the other events of Ahab's reign, including all he did, the palace he built and inlaid with ivory, and the cities he fortified, are they not written in the book of the annals of the kings of Israel? Ahab rested with his fathers. And Ahaziah his son succeeded him as king. (1 Kings 22:39-40)

Sadly those annals appear to be lost.

The allusions to the statutes and works of Omri and Ahab in Micah 6:16 seem to point to legislative measures of these kings to which the prophet objected, perhaps guaranteeing the right of Canaanite religious worship alongside of Yahwism.

Legacy

Ahab's son Ahaziah of Israel died soon after his accession and was succeeded by his brother Joram. Joram vigorously prosecuted the war with Damascus, but internal opposition by the prophets of Yahweh grew stronger. The prophet Elisha went so far as to anoint the Syrian leader Hazael to punish Israel's toleration of Baal worship and instigated a coup d'ĂŠtat against Joram by the military leader Jehu. Joram and his mother, Jezebel, were soon put to death together with their entire extended family, just as Elijah had earlier predicted. A widespread slaughter of the priests of the Baal followed.

Probably during one of Ahab's meetings with Jehoshophat of Israel, a marriage pact was concluded resulting in Ahab and Jezebel's daughter Athaliah being married to Jehoram of Judah. Athaliah would eventually seize the throne in Jerusalem, where she ruled for seven years. She, too, would soon be assassinated for her support of Baal worship and was succeeded by her grandson, Jehoash. Thus, the line of Ahab ultimately converged with that of David, and became part of the lineage of the Messiah to come.

The Historical Ahab

Often overlooked in the Bible's story of Ahab is the fact that, by external standards, he was one of Israel's greatest kings. The material prosperity of Ahab's reign is comparable with that of Solomon a century before. However, this is overshadowed by the religious controversy which his marriage involved, coming just at the time when the "Yahweh-only" movement was getting its start among certain of the prophets.

Ahab's wife was firmly attached to the worship of Melkart (the Tyrian Baal). Ahab gave support to her religious tradition by building a temple in honor of Baal in his capital, Samaria. This roused the indignation of those among the Yahwist prophets who adamantly insisted that all worship of foreign deities be banned within Israel's borders. In this respect, it is noteworthy that Mount Carmel itself commanded the heights between Israel and Phoenicia. It was thus not only a battle to determine which god could actually produce rain, but which of the gods would control the strategic "high ground."

That Ahab himself recognized Yahweh is clear both from the biblical narrative and the names of Ahab's children (1 Kings 22:5). Ahab also received the support at least one "true" prophet, along with the many Yahwist court prophets who advised him at the meeting with Jehoshaphat. Clearly, not all of the prophets of Yahweh shared Elijah's disdain for the king.

Ahab's substantial accomplishments can be easily lost in the biblical narrative's agenda to portray him as a one who "did more evil in the eyes of the Lord than any of those before him" (1 Kings 17:30). During Ahab's reign, Moab, which had been conquered by his father, remained a tributary to Israel. Ahab also ended the previous enmity with Judah. Jehoshaphat, with whom he was allied by marriage, was also probably Ahab's vassal and clearly did his bidding at the battle of Ramoth Gilead. Relations with the rich trading cities of Phoenicia further benefited Ahab's reign. Only with Damascus is he said to have had strained relations, and there too, he proved victorious. His building projects, though described in the Bible only sketchily, were impressive, and archaeological evidence tends to support the hypothesis that Ahab may have been even a greater potentate than the Bible suggests.

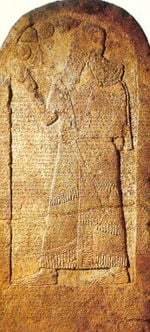

Unlike either David or Solomon, Ahab's kingdom was substantial enough to merit at least one mention in the extra-biblical recordâin the record of the Battle of Qarqar (853 B.C.E.). Shalmaneser III of Assyria memorialized the battle in an inscription in which he described his adversaries as a major confederation of princes under Hadadezer (Ben-Hadad) of Syria. "Ahab the Israelite" is named as one of Shalmaneser's enemies.[1] Ahab is described as contributing two thousand chariots and ten thousand soldiers to the campaign, giving him the region's largest chariot force and confirming the biblical mention of the importance Ahab placed on pastureland for his horses.

Historians debate the relation of the Shalmaneser inscription to the biblical record. While Shalmaneser sees Ben-Hadad as the leader of a coalition to which Ahab owed allegiance, the Bible claims that Ahab had previously defeated Ben-Hadad and his 32 kings. The Bible also speaks of Ahab's remarkable victory over Ben-Hadad at Aphek (1 Kings 20). A treaty was made whereby Ben-hadad restored the cities which his father had taken from Ahab's father and Israelite merchants were allowed to set up their shops in Damascus.

In any case, the Bible also records that three years after the treaty with Ben-Hadad, war broke out again on the east of the Jordan River. Ahab, with Jehoshaphat of Judah, went to recover Ramoth-Gilead and was mortally wounded (1 Kings 22). He was succeeded by his sons (Ahaziah and Jehoram).

A great deal of archaeological research recently has provided new insights into Ahab's kingdom. Israel Finkelstein, who has supervised extensive digs at Samaria and Megiddo, believes that Omri and Ahab should be credited with much of the monumental building attributed in the Bible to Solomon, including not only palaces and walls, but also "Solomon's" famous stables.[2]

In Rabbinical literature

Certain of the rabbis list Ahab as one of the wicked kings of Israel and consider him to be so evil as to be excluded from the the possibility of future redemption (Sanh. 10:2). However, several rabbinical authorities recognize noble traits of character in Ahab (Sanh. 10:2b). For example, he is said to have generously supported Torah students out of the state treasury. For this, half of his sins were forgiven.

Since it was Jezebel that instigated most of Ahab's crimes, some ancient authorities consider him as having the status of a repentant sinner (Sanh. 104b; Num. R. 14). His fasts are described as lasting for a long time, and he is said to have prayed three times a day to God for forgiveness. Eventually, his prayer was accepted (Pirke R. El. 43). When the impressive number of 230 vassal kings rebelled against him, Ahab brought their sons to Samaria and Jerusalem as hostages, successfully turning them from idolaters into worshipers of Yahweh (Tanna debe Eliyahu, 1:9). Thus, in several of the lists of the wicked kings, Ahab's name has been replaced by that of Ahaz (Yer. Sanh. 10:28b; Tanna debe Eliyahu Rabba 9; Zutta 24).

Ahab's power is thought by the rabbis to have been immense. According to one ancient tradition (Meg. 11a), Ahab was the ruler of the whole world. Moreover, not only Ahab himself, but each of his 70 sons is said to have lived in an ivory palace.

Notes

- â Bryant G. Wood, Ahab the Israelite. Associates for Biblical Research, January 2, 2006. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- â Israel Finkelstein, A Great United Monarchy? Archaeological and Historical Perspectives Retrieved January 7, 2019.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ahab â Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- Albright, William F. The Archeology of Palestine. Magnolia, MA: Peter Smith Pub. Inc., 2nd edition, 1985. ISBN 0844600032

- Bright, John. A History of Israel. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 4th edition, 2000. ISBN 0664220681

- Finkelstein, Israel. David and Solomon: In Search of the Bible's Sacred Kings and the Roots of the Western Tradition. Free Press, 2006. ISBN 0743243625

- Galil, Gershon. The Chronology of the Kings of Israel and Judah. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 1996. ISBN 9004106111

- Grant, Michael. The History of Ancient Israel. New York: Scribner, 1984. ISBN 0684180812

- Keller, Werner. The Bible as History. New York: Bantam, 1983. ISBN 0553279432

- Miller, J. Maxwell. A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1986. ISBN 066421262X

| Preceded by: Omri |

King of Israel Albright: 869 B.C.E. â 850 B.C.E. Thiele: 874 B.C.E. â 853 B.C.E. Galil: 873 B.C.E. â 852 B.C.E. |

Succeeded by: Ahaziah |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.