Omri

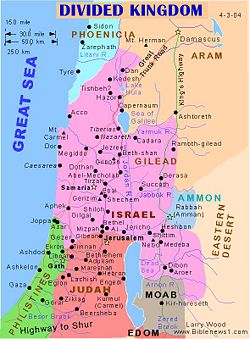

Omri (Hebrew עָמְרִי, short for עָמְרִיָּה—"The Lord is my life") was king of Israel c. 885–874 B.C.E. and the founder of the capital city of Samaria. He was the father of Israel's famous king Ahab and the grandfather of two other kings of Israel. In addition, Omri's granddaughter Athaliah reigned as queen of Judah for several years.

Omri took power during a period of political instability in the northern kingdom. His rule over Israel was secure enough that he could bequeath his kingdom to his son Ahab, thus beginning a new dynasty. Archaeologists consider the Omride dynasty to have been a major regional power, and some of the monumental building projects attributed to Solomon by the biblical writers have recently been dated to the period of Omri's rule. Omri is the first king of Israel or Judah to be mentioned in any historical record outside of the Bible.

The writers of the Books of Kings barely mention Omri's political and economic accomplishments, considering him an evil king who repeated the sin of the northern king Jeroboam I by refusing to acknowledge the Temple of Jerusalem as the only legitimate Israelite religious shrine. Both contemporary archeology and the modern state of Israel, however, evaluate him more positively. Some Israeli archaeologists (see Finkelstein 2001) believe that Omri and his descendants, rather than David or Solomon, "established the first fully developed monarchy in Israel."

Omri's being Athaliah's grandfather, though rarely mentioned as such, makes him one of the ancestors of Jesus Christ, according to New Testament tradition, and one of the ancestors of the Davidic Messiah in Judaism.

Omri in the Bible

Omri ended a period of political instability in the Kingdom of Israel following the death of its founder, Jeroboam I, who had led a successful revolt against King Solomon's son, Rehoboam, to establish an independent nation consisting of the ten northern Israelite tribes. Jeroboam's son, Asa, reigned only two years before being overthrown by Baasha, who proceeded to wipe out any surviving descendants of Jeroboam. Baasha pursued a policy of war against the southern Kingdom of Judah but had to abandon this effort due to military pressure from the Aramaean kingdom of Damascus. He was succeeded by his son Elah, who was overthrown after two years by one of his own officials, Zimri.

Omri had been the commander of the army under Elah. With Zimri claiming the kingship, Omri's troops proclaimed him as legitimate ruler. Omri and his forces then marched to the capital of Tirzah, where they trapped Zimri in the royal palace. The Bible reports that Zimri burned the palace down and died in the inferno rather than surrender (1 Kings 16:15–19). Although Zimri was eliminated after only seven days in power, "half of the people" supported a certain Tibni in opposition to Omri. Fighting between the two sides seems to have continued for several years until Omri was finally recognized as the undisputed king (1 Kings 16:21–23).

The Bible credits Omri with having built the city of Samaria as his capital in the seventh year of his reign (1 Kings 16:23–24). He faced military attacks from the kingdom of Syria (Damascus) and was forced for a time to allow Syrian merchants to open markets in the streets of Samaria (1 Kings 29:34). However, Omri soon gained the upper hand against Damascus, and the new city remained the capital of Israel as long as the nation survived, for more than 150 years. Samaria was strongly fortified and endured several sieges before its downfall.

Omri also strengthened his kingdom through alliances with his northern and southern neighbors against the threat of Damascus (Syria) and Assyria to the east. He facilitated a marriage between his son and heir, Ahab, and the Phoenician princess Jezebel, daughter of Ethbaal. Animosities were also ended with the southern Kingdom of Judah, and Ahab later arranged a marriage between his daughter, Athaliah, and King Jehoshaphat of Judah, with whom he contracted a military alliance.

Omri alienated the biblical writers, however, by following Jeroboam's policy of promoting shrines other than the Temple of Jerusalem as officially sanctioned pilgrimage sites where citizens of his kingdom could offer tithes and sacrifices. For this, he was denounced as following in the "ways of Jeroboam son of Nebat and in his sin, which he had caused Israel to commit." (1 Kings 16:25)

The Omride dynasty

Like all of the northern kings, Omri left no record yet uncovered to tell his own version of events. However, he is the first king of either Israel or Judah who is mentioned by historical sources outside of the Bible.

Recent historians believe that the dynasty founded by Omri constitutes a new chapter in the history of the northern Kingdom of Israel. Omri ended almost 50 years of constant civil war over the throne. Under his reign, there was peace with the Kingdom of Judah to the south, while relations with neighboring Phoenicans to the north were bolstered by marriages negotiated between the two royal courts. This state of peace with two powerful neighbors enabled the Kingdom of Israel to expand its influence and even political control in Transjordan, and these factors combined brought economic prosperity to the kingdom.

Israeli archaeologist Israel Finkelstein (2001) refers to Omri's reign as "Israel's forgotten first kingdom." He notes that during the earlier reigns of David and Solomon, "political organization in the region had not yet reached the stage where extensive bureaucraces" had developed. This had changed by the time of the Omrides, however. Finkelstein and his colleagues have also done extensive work on large buildings formally attributed to Solomon, which he now dates as originating in Omri's days.

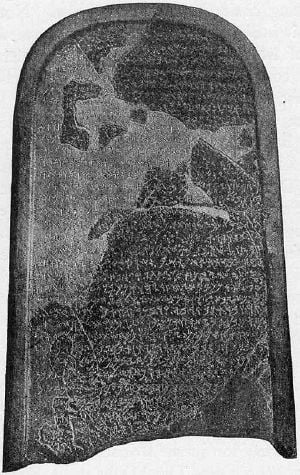

Omri is credited in the Mesha steele as having brought the territory of Moab under his dominion. The Moabite king Mesha admits:

Omri [was] king of Israel, and he oppressed Moab many days, for Chemosh was angry with His land. And his son succeeded him, and he too said, "I will humble Moab."

In the Tel Dan inscription, a Syrian king (probably Hazael) admits that "the kings of Israel entered my father's land," indicating that the Omride dynasty controlled territory in Syria, stretching south through Moab. A sizable army is also evidenced, as shown in the inscription of the Assyrian leader Shalmaneser III (858–824 B.C.E.) who refers to an opposing force of 2,000 chariots and 10,000 footsoldiers belonging to Omri's son, "Ahab the Israelite."

Assyrian sources referred to Israel as the "land of the house of Omri," or the "land of Omri" for nearly 150 years. Even Jehu, who ended the Omride dynasty, was mistakenly called "the son of Omri" by Shalmaneser II.

Archaeological evidence regarding the construction of palaces, stables, and store cities indicates that Israel under the Omrides had surpassed its southern neighbor. The site of Omri and Ahab's impressive palace at Samaria has been uncovered for more than a century. Moreover, recent investigations have reassigned the dates of several important structures formerly attributed to Solomon to the time of Omri and Ahab. Impressive fortifications, administrative centers, and other improvements at Megiddo and Hazor led Finklestein and others to conclude that "The Omrides, not Solomon, established the first fully developed monarchy in Israel."

Externally, Omri is thus increasingly recognized as a major Israelite king. However, it is also clear that he faced internal opposition from adversaries whose allies ultimately gave him and his descendants an infamous place in biblical history. Peace with Phoenicia, while increasing trade and stability, also resulted in the penetration of Phoenician religious traditions into the kingdom. This led to a violent struggle between the Yahweh-only party (as personified by the prophets Elijah and Elisha) and the aristocracy (as personified by Omri, Ahab, Jezebel, and their descendants).

The animosity of the Yahweh-only group to the Omrides' support of Phoenician Baal worship led to the famous fight between the prophets of Baal and the prophet Elijah on Mount Carmel, after which Elijah ordered the slaughter of all 450 of his defeated opponents. His successor, Elisha, reportedly anointed Hazael to replace Ben Hadad III on the throne of Damascus and simultaneously appointed the military commander Jehu to usurp the throne from Ahab's descendants and slaughter his entire family, including Jezebel. Jehu's simultaneous assassination of Israel's ally, Ahaziah of Judah, paradoxically led to the Omride princess Athaliah, Ahaziah's mother, seizing the throne at Jerusalem and reigning there for seven years.

Meanwhile Assyria was beginning to expand westward from Mesopotamia. The Battle of Qarqar (853 B.C.E.) pitted Shalmaneser III of Assyria against a coalition of local kings, including Ahab. It was the first in a series of wars that would eventually lead to the destruction of the Kingdom of Israel in 722 B.C.E. and the reduction of the Kingdom of Judah to an Assyrian tributary state.

Legacy

Omri solidified the foundations of the northern Kingdom of Israel, which had begun to weaken in the decades following Jeroboam I's establishment of the northern federation as an independent nation. His creation of the new capital of Samaria was a lasting contribution to Israel's history. The city not only survived as the richest city in either Israel or Judah until Israel's destruction in 722 B.C.E., but was later rebuilt as the capital of the Samaritan Kingdom of Samaria and became a showcase city for Herod the Great in the late first century B.C.E. under the new name of Sebaste. Omri's dynasty made peace with both Judah and Phoenicia, and resisted military attacks by both the Syrian and Assyrian empires. It was not until the usurper Jehu, supported by the prophet Elisha, took the throne that Israel was reduced to being a vassal of the Assyrian power.

In biblical tradition, however, Omri is the founder of an evil dynasty; his close relations with Phoenicia resulted in a political marriage between his son Ahab and the Baal-worshiping princess Jezebel, who brought with her a religious tradition absolutely unacceptable from the standpoint of the Bible. It was her introduction of Baal worship, much more than Omri's own support of the national Yahwist shrines at Dan and Bethel, which brought the wrath of the prophets Elijah and Elisha on Omri's descendants.

While both the Bible and rabbinical tradition take a negative view toward Omri, the modern State of Israel, not to mention several prominent Israeli archaeologists, has recently re-evaluated his contribution to Israel's history. Academics now view him as the founder of the Hebrews' first true kingdom, viewing the governments of David and Solomon more as mere tribal federations whose accomplishments were glorified by later biblical writers. Modern Israel, meanwhile, tends to view Israelite warrior kings such as Omri rather positively, even when they are not seen as shining examples of biblical piety. Indeed, in present-day Israeli society, "Omri" is a fairly common male name. Omri Sharon, the elder son of former Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, is a well-known example. Omri Katz is an Israeli-American actor, born in Los Angeles to Israeli parents.

Omri's granddaughter Athaliah married Jehoram, king of Judah, and her grandson, Joash of Judah, survived to have royal sons of his own. This puts both Athaliah and Omri in the ancestral line of the Davidic Messiah in Jewish tradition and the lineage of Jesus Christ in Christian tradition.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Albright, William F. 1985. The Archaeology of Palestine. 2nd edition. Peter Smith Pub Inc. ISBN 0844600032

- Bright, John. 2000. A History of Israel. 4th edition. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0664220681

- Finkelstein, Israel. 2001. The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0684869128

- Finkelstein, Israel. 2006. David and Solomon: In Search of the Bible's Sacred Kings and the Roots of the Western Tradition. Free Press. ISBN 0743243625

- Galil, Gershon. 1996. The Chronology of the Kings of Israel and Judah. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 9004106111

- Keller, Werner. 1983. The Bible as History. 2nd Rev. edition. Bantam. ISBN 0553279432

- Miller, J. Maxwell, and Hayes, John H. 1986. A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 066421262X

- Thiele, Edwin R. 1994. The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings. Reprint edition. Kregel Academic and Professional. ISBN 082543825X

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.