Yupik

| Yupik |

|---|

|

| Total population |

| 21,000 |

| Regions with significant populations |

| Languages |

| Yupik languages, English, Russian (in Siberia) |

| Religions |

| Christianity (mostly Russian Orthodox), Shamanism |

| Related ethnic groups |

| Inuit, Sirenik, Aleut |

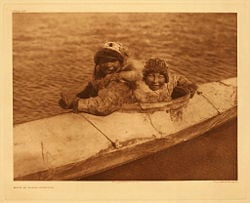

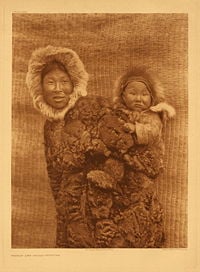

The Yupik or, in the Central Alaskan Yup'ik language, Yup'ik, are a group of indigenous or aboriginal peoples of western, southwestern, and southcentral Alaska and the Russian Far East. They include the Central Alaskan Yup'ik people of the Yukon-Kuskokwim delta, the Kuskokwim River, and coastal Bristol Bay in Alaska; the Alutiiq (or Suqpiaq) of the Alaska Peninsula and coastal and island areas of southcentral Alaska; and the Siberian Yupik of the Russian Far East and St. Lawrence Island in western Alaska. They are Eskimo and are related to the Inuit.

History

The common ancestors of Eskimos and Aleuts (as well as various Paleo-Siberian groups) are believed by archaeologists to have their origin in eastern Siberia and Asia, arriving in the Bering Sea area about 10,000 years ago.[1] By about 3,000 years ago the progenitors of the Yupiit had settled along the coastal areas of what would become western Alaska, with migrations up the coastal rivers—notably the Yukon and Kuskokwim—around 1400 C.E., eventually reaching as far upriver as Paimiut on the Yukon and Crow Village on the Kuskokwim.[2]

The environment of the Yup'ik, below the Arctic Circle, is different from that of the barren, icy plains of the northern Eskimos. They lived mostly in marshlands that were crossed by many waterways, which the Yup'ik used for travel and transporation.[3] Due to the more moderate climate, hunting and fishing could continue for most of the year.

The Yup'ik had contact with Russian explorers in the 1800s, later than the Northern peoples. Unlike the earlier explorers of the 1600s who regarded the Arctic Eskimos as savages, these later Russians regarded them more favorably, allowing them to continue their traditional way of life with a focus on the extended family, and speak their own language. The Russian Orthodox Church missionaries who brought Christianity lived among the Yup'ik in the late 1800s; the Yup'ik selected elements of Christian belief to integrate with their traditional beliefs.[3]

Central Alaskan Yup'ik

The Yup'ik people (also Central Alaskan Yup'ik, plural Yupiit), are an Eskimo people of western and southwestern Alaska ranging from southern Norton Sound southwards along the coast of the Bering Sea on the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta (including living on Nelson and Nunivak Islands) and along the northern coast of Bristol Bay as far east as Nushagak Bay and the northern Alaska Peninsula at Naknek River and Egegik Bay.

The Yupiit are the most numerous of the various Alaska Native groups and speak the Central Alaskan Yup'ik language.[4] The people of Nunivak Island, speakers of the Nunivak Island dialect of Central Alaskan Yup'ik, call themselves Cup'ig (plural Cup'it); the people of Hooper Bay and Chevak, speakers of the Hooper Bay-Chevak dialect, call themselves Cup'ik (plural Cup'it).

As of the 2000 U.S. Census, the Yupiit population in the United States numbered over 24,000,[5] of whom over 22,000 lived in Alaska, the vast majority in the seventy or so communities in the traditional Yup'ik territory of western and southwestern Alaska.[6]

Etymology of name

Yup'ik (plural Yupiit) comes from the Yup'ik word yuk meaning "person" plus the post-base -pik meaning "real" or "genuine." Thus, it means literally "real people."[2] The ethnographic literature sometimes refers to the Yup'ik people or their language as Yuk or Yuit. In the Hooper Bay-Chevak and Nunivak dialects of Yup'ik, both the language and the people are given the name Cup'ik.[4]

Alutiiq

The Alutiiq (plural: Alutiit), also called Pacific Yupik or Sugpiaq, are a southern coastal people of the Yupik peoples of Alaska. Their language is also called Alutiiq. They are not to be confused with the Aleuts, who live further to the southwest, including along the Aleutian Islands. Through a confusion among Russian explorers in the 1800s, these Yupik people were erroneously called "Alutiiq," meaning Aleut in Yupik. This term has remained in use to the present day.

They traditionally lived a coastal lifestyle, subsisting primarily on ocean resources such as salmon, halibut, and whale, as well as rich land resources such as berries and land mammals. Before European contact with Russian fur traders, the Alutiiq lived in semi-subterranean homes called barabaras.

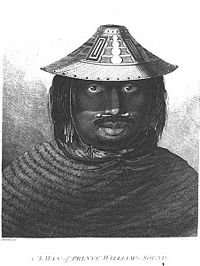

Chugach

Chugach (pronounced /ˈtʃuːgætʃ/) is the name of an Alaska Native culture and group of people in the region of the Kenai Peninsula and Prince William Sound. The Chugach people are an Alutiiq (Pacific Eskimo) people who speak the Chugach dialect of the Alutiiq language.

The Chugach people gave their name to Chugach National Forest, the Chugach Mountains, and Alaska's Chugach State Park, all located in or near the traditional range of the Chugach people in southcentral Alaska.

Siberian Yupik

Siberian Yupiks, or Yuits, are indigenous people who reside along the coast of the Chukchi Peninsula in the far northeast of the Russian Federation and on St. Lawrence Island in Alaska. They speak Central Siberian Yupik (also known as Yuit), a Yupik language of the Eskimo-Aleut family of languages.

They were also known as Siberian Eskimo or Yupiks. The name Yuit (Юит, plural: Юиты) was officially assigned to them in 1931, at the brief time of the campaign of support of indigenous cultures in the Soviet Union.

Languages

The five Yupik languages (related to Inuktitut) are still very widely spoken, with more than 75 percent of the Yupik/Yup'ik population fluent in the language.

The Alaskan and Siberian Yupik, like the Alaskan Inupiat, adopted the system of writing developed by Moravian missionaries during the 1760s in Greenland. The Alaskan Yupik and Inupiat are the only Northern indigenous peoples to have developed their own system of hieroglyphics, a system that died with its inventors.[7]

Culture

Lifestyle

Traditionally, Yup'ik families spent the spring and summer at fish camp, and then joined with others at village sites for the winter. Edible greens and berries grow profusely in the summer, and there are numerous birch and spruce trees also. In contrast to the Northern Eskimos who built igloos for shelter, the Yup'ik used trees and driftwood to build permanent winter homes, separate buildings for the men and the women.[3]

The men's communal house, the qasgiq, was the community center for ceremonies and festivals which included singing, dancing, and storytelling. The qasgiq was used mainly in the winter months, because people would travel in family groups following food sources throughout the spring, summer, and fall months. Aside from ceremonies and festivals, it was also where the men taught the young boys survival and hunting skills, as well as other life lessons. The young boys were also taught how to make tools and qayaqs (kayaks) during the winter months in the qasgiq.

The women's house, the ena, was traditionally right next door, and in some areas they were connected by a tunnel. Women taught the young girls how to sew, cook, and weave. Boys would live with their mothers until they were about five years old, then they would live in the qasgiq. Each winter, from anywhere between three to six weeks, the young boys and young girls would exchange, with the men teaching the girls survival and hunting skills and toolmaking and the women teaching the boys how to sew and cook.

The winter building of Siberian Yupik, called yaranga (mintigak in the language of Chaplino Eskimos (Ungazigmit)), was a round, dome-shaped building. Its framework was made of posts. In the middle of the twentieth century, following external influence, canvas was used for the covering the framework. The yaranga was surrounded by sod or planking at the lower part. There was another smaller building inside it, used for sleeping and living. Household works were done in the room surrounding this inner building, and also many household utensils were stored there.[8] At night and during winter storms the dogs were brought inside the outer part of the building.

Villages consisted of groups of as many as 300 persons, tied together by blood and marriage. Marriage could take place beyond members of the immediate village, but remained with the larger regional group, as the regional groups were often at war with each other.[3]

Spirituality

Shamanism

Many indigenous cultures had persons acting as mediators with the spirit world, contacting the various entities (spirits, souls, and mythological beings) that populate the universe of their belief system.[10] These were usually termed “shamans” in the literature, although the term as such was not necessarily used in the local language. For example, the Siberian Yupik called these mediators /aˈliɣnalʁi/, which is translated as "shaman" in both Russian and English literature.[11][12][13] Ungazigmit people (the largest of Siberian Yupik variants) had /aˈliɣnalʁi/s, who received presents for shamanizing, or healing. This payment had a special name, /aˈkiliːɕaq/, in their language.[14]

Unlike many Siberian traditions, in which spirits "force" individuals to become shamans, most Yup'ik shamans choose this path. Even when someone receives a "calling," that individual may refuse it.[15] The process of becoming a Yup'ik shaman usually involves difficult learning and initiation rites, sometimes including a vision quest. Some Yup'ik shamans are believed to have special qualifications: they may have been an animal during a previous period, and thus be able to use their valuable experience for the benefit of the community.[16]

The initiation process varies. It may include a specific kind of vision quest, such as among the Chugach. Chugach apprentice shamans were not forced to become shamans by the spirits, but instead deliberately visited lonely places and walked for many days as part of a vision quest that resulted in the visitation of a spirit. The apprentice passed out, and the spirit took him or her to another place (like the mountains or the depths of the sea). Whilst there, the spirit instructed the apprentice in their calling, such as teaching them the shaman’s song.[17]

The boundary between shaman and lay person was not always clearly demarcated. Non-shamans could also experience hallucinations,[18][19] and many reported memories of ghosts, animals in human form, or little people living in remote places.[20] The ability to have and command helping spirits was characteristic of shamans, but laic people (non-shamans) could also profit from spirit powers through the use of amulets. Some laic people had a greater capacity than others for close relationships with special beings of the belief system; these people were often apprentice shamans who failed to complete their learning process.[15]

Amulets

Amulets could be manifested in many forms, reflecting beliefs about the animal world. The orca, wolf, raven, spider, and whale were revered animals, as demonstrated in numerous folklore examples. For example, a spider saves the life of a girl.[21][22]

Amulets could be used to protect an individual person or the entire family. Thus, a head of raven hanging on the entrance of the house functioned as a family amulet[23]. Figures carved out of stone in the shape of walrus head or dog head were often worn as individual amulets.[24]

Concepts about the animal world around them

- Orca and wolf;

In the tales and beliefs of this people, wolf and orca are thought to be identical: orca can become a wolf or vice versa. In winter, they appear in the form of wolf, in summer, in the form of orca.[25][26][13][27] Orca was believed to help people in hunting on the sea—thus the boat represented the image of this animal, and the orca's wooden representation hang also from the hunter's belt.[13] Also small sacrifices could be given to orcas: tobacco was thrown into the sea for them, because they were thought to help the sea hunter in driving walrus.[28] It was believed that the orca was a help of the hunters even if it was in the guise of wolf: this wolf was thought to force the reindeer to allow itself to be killed by the hunters.[27]

- Whale

There were also hunting amulets, worn attached to something or worn directly, to bring success in the hunt.[29]

Siberian Yupiks stressed the importance of maintaining a good relationship with sea animals.[27] It is thought that during the hunt only those people who have been selected by the spirit of the sea could kill the whale. The hunter has to please the killed whale: it must be treated as a guest. Just like a polite host does not leave a recently arrived dear guest alone, thus similarly, the killed whale should not be left alone by the host (i.e. by the hunter who has killed it). Like a guest, it should not get hurt or feel sad. It must be entertained (e.g. by drum music, good foods).

It was thought that the prey of the marine hunt could return to the sea and become a complete animal again. That is why they did not break the bones, only cut them at the joints.[30] On the next whale migration (whales migrate twice a year, in spring to the north and in the autumn back), the previously killed whale is sent off back to the sea in the course of a farewell ritual. If the killed whale was pleased to (during its being a guest for a half year), then it can be hoped that it will return later, too: thus, also the future whale hunts will succeed.[31][32]

Name-giving

The Yup'ik are unique among native peoples of the Americas in that children are named after the last person in the community to have died, whether that name be of a boy or girl. Among Siberian Yupik it was believed that the deceased person was affected and a certain rebirth was achieved. Even before the birth of the baby, careful investigations took place: dreams and events were analyzed. After the birth, the baby's physical traits were compared to those of the deceased person. The name was important: if the baby died, it was thought that he/she has not given the "right" name. In case of sickness, it was hoped that giving additional names could result in healing.[33]

Art

The Siberian Yupik on St. Lawrence Island live in the villages of Savoonga and Gambell, and are widely known for their skillful carvings of walrus ivory and whale bone, as well as the baleen of bowhead whales. These even include some “moving sculptures” with complicated pulleys animating scenes such as walrus hunting or traditional dances.

For the Yup'ik, masked dancing has long played an important role in ceremonies, traditionally performed inside the Gasgiq. Often used by shamans to facilitate communication between the worlds of human beings and others, the masks make visible the world of spirits. As they were generally discarded after use, numerous specimens were retrieved by traders and collectors, and many are now found in museums. Representing a wide variety of animals, particularly wolves, seals, and loons, as well as legendary creatures, such masks have inspired collectors and artists. But their spiritual power, breathing life into the stories of the performers, is in many cases only a memory recalled by elders from the days when these masks were their "way of making prayer."[34]

Yup'ik group dances are often with individuals staying stationary, with all the movement done with rhythmic upper body and arm movements accentuated with hand held dance fans very similar to Cherokee dance fans. The limited movement area by no means limits the expressiveness of the dances, which cover the whole range from graceful flowing, to energetically lively, to wryly humorous.

Contemporary lifestyle

Many families still harvest the traditional subsistence resources, especially salmon and seal.

The Alutiiq today live in coastal fishing communities, where they work in all aspects of the modern economy, while also maintaining the cultural value of subsistence.

Notable contemporary Alutiiq include painter and sculptor, Alvin Eli Amason, and Sven Haakanson, executive director of the Alutiiq Museum, and winner of a 2007 MacArthur Fellowship.[35]

Many of the Chugach people are shareholders of the Chugach Alaska Corporation, an Alaska Native regional corporation created under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971.

Notes

- ↑ Naske and Slotnick, 1987, p. 18.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Fienup-Riordan, 1993, p. 10.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Ann Fienup-Riordan, Eskimo Essays: Yup'ik Lives and How We See Them (Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0813515892)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Alaska Native Language Center. (2001-12-07). "Central Alaskan Yup'ik." University of Alaska Fairbanks. Retrieved on 2007-04-12.

- ↑ U.S. Census Bureau. (2004-06-30). "Table 1. American Indian and Alaska Native Alone and Alone or in Combination Population by Tribe for the United States: 2000." American Indian and Alaska Native Tribes for the United States, Regions, Divisions, and States (PHC-T-18). U.S. Census Bureau, Census 2000, special tabulation. Retrieved on 2007-04-12.

- ↑ U.S. Census Bureau. (2004-06-30). "Table 16. American Indian and Alaska Native Alone and Alone or in Combination Population by Tribe for Alaska: 2000." American Indian and Alaska Native Tribes for the United States, Regions, Divisions, and States (PHC-T-18). U.S. Census Bureau, Census 2000, special tabulation. Retrieved on 2007-04-12.

- ↑ "The Inuktitut Language" in Project Naming, the identification of Inuit portrayed in photographic collections at Library and Archives Canada

- ↑ Рубцова 1954

- ↑ Ann Fienup-Riordan. Boundaries and Passages: Rule and Ritual in Yup'ik Eskimo Oral Tradition. (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994), 206.

- ↑ Mihály Hoppál, Sámánok Eurázsiában (Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 2005, ISBN 9630582953) 45–50.

- ↑ Рубцова 1954:203–19

- ↑ Menovščikov 1968:442

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Духовная культура (Spiritual culture), subsection of Support for Siberian Indigenous Peoples Rights (Поддержка прав коренных народов Сибири)—see the section on Eskimos

- ↑ Рубцова 1954:173

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Kleivan & Sonne 1985

- ↑ Rasmussen, Knud, ed. and coll. 1921 "The Soul that Lived in the Bodies of All Beasts," in Eskimo Folk-Tales, ed. and trans. W. Worster, with illustrations by native Eskimo artists, 100. London: Gyldendal.

- ↑ Daniel Merkur, Becoming Half Hidden: Shamanism and Initiation among the Inuit (Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1985, ISBN 91-22-00752-0), 125.

- ↑ Merkur 1985:41–42

- ↑ Gabus 1970:18,122

- ↑ Merkur 1985:41

- ↑ Menovščikov 1968:440–441

- ↑ Рубцова 1954, tale 13, sentences (173)–(235)

- ↑ Рубцова 1954:380

- ↑ Рубцова 1954:380,551–552

- ↑ Рубцова 1954:156 (see tale The orphan boy with his sister)

- ↑ Menovščikov 1968:439,441

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Edward J. Vajda Siberian Yupik (Eskimo) East Asian Studies Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "submit" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ (Russian) A radio interview with Russian scientists about Asian Eskimos

- ↑ Рубцова 1954:380

- ↑ Рубцова 1954:379

- ↑ Menovščikov 1968:439–440

- ↑ Рубцова 1954:218

- ↑ Burch & Forman 1988: 90

- ↑ Ann Fienup-Riordan, The Living Tradition of Yup'Ik Masks: Agayuliyararput : Our Way of Making Prayer (University of Washington Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0295975016)

- ↑ MacArthur Fellows 2007 The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Retrieved July 2, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Fienup-Riordan, Ann. Eskimo Essays: Yup'ik Lives and How We See Them. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0813515892

- Fienup-Riordan, Ann. Boundaries and Passages: Rule and Ritual in Yup'ik Eskimo Oral Tradition. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0806126463

- Fienup-Riordan, Ann. The Living Tradition of Yup'Ik Masks: Agayuliyararput : Our Way of Making Prayer. University of Washington Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0295975016

- Campbell, Lyle. American Indian languages: The historical linguistics of Native America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. ISBN 0195094271

- Mithun, Marianne. The languages of Native North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 0521232287

- de Reuse, Willem J. Siberian Yupik Eskimo: The language and its contacts with Chukchi. Studies in indigenous languages of the Americas. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1994. ISBN 0874803977

- Kleivan, Inge, and B. Sonne. Eskimos, Greenland and Canada (Iconography of Religions Section 8 - Arctic Peoples). Brill Academic Publishers, 1997. ISBN 9004071601

- Merkur, Daniel. Becoming Half Hidden: Shamanism and Initiation among the Inuit. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell, 1985. ISBN 9122007520

- Burch, Ernest S. (junior) and Werner Forman. The Eskimos. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1988. ISBN 0806121262

- Hoppál, Mihály. Sámánok Eurázsiában (in Hungarian). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 2005. ISBN 9630582953. (The title means "Shamans in Eurasia," the book is written in Hungarian, but it is also published in German, Estonian and Finnish).

- Menovščikov (Меновщиков), G. A. "Popular Conceptions, Religious Beliefs and Rites of the Asiatic Eskimos." In Popular beliefs and folklore tradition in Siberia edited by Vilmos Diószegi. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1968.

- Menovshchikov (Меновщиков), Georgy. "Contemporary Studies of the Eskimo-Aleut Languages and Dialects: A Progress Report." In Arctic Languages: An Awakening edited by Dirmid R. F. Collis, 69–76. Vendôme: UNESCO, 1990. ISBN 9231026615

- Рубцова, Е. С. Материалы по языку и фольклору эскимосов (чаплинский диалект) (in Russian). Москва: Российская академия наук, 1954. Transliteration of author's name, and the rendering of title in English: Rubcova, E. S. Materials on the Language and Folklore of the Eskimos, Vol. I, Chaplino Dialect. Moscow: Russian Academy of Sciences.

- Krupnik, Igor, and Nikolay Vakhtin. 1997. "Indigenous Knowledge in Modern Culture: Siberian Yupik Ecological Legacy in Transition." Arctic Anthropology. 34, no. 1: 236.

- Crowell, Aron, Amy F. Steffian, and Gordon L. Pullar. Looking Both Ways Heritage and Identity of the Alutiiq People. Fairbanks, Alaska: University of Alaska Press, 2001. ISBN 1889963305

- Braund, Stephen R. & Associates. Effects of the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill on Alutiiq Culture and People. Anchorage, Alaska: Stephen R. Braund & Associates, 1993.

- Lee, Molly. 2006. "If It's Not a Tlingit Basket, Then What Is It?": Toward the Definition of an Alutiiq Twined Spruce Root Basket Type." Arctic Anthropology. 43(2): 164.

- Luehrmann, Sonja. Alutiiq Villages Under Russian and U.S. Rule. Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska Press, 2008. ISBN 9781602230101

- Mishler, Craig, and Rachel Mason. "Alutiiq Vikings: Kinship and Fishing in Old Harbor, Alaska." Human Organization : Journal of the Society for Applied Anthropology. 55(3) (1996): 263.

- Mulcahy, Joanne B. Birth & Rebirth on an Alaskan Island The Life of an Alutiiq Healer. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2001. ISBN 0820322539

- Partnow, Patricia H. Making History Alutiiq/Sugpiaq Life on the Alaska Peninsula. Fairbanks, Alaska: University of Alaska Press, 2001. ISBN 1889963380

- Simeonoff, Helen J., and Alphonse Pinart. Origins of the Sun and Moon Alutiiq Legend from Kodiak Island, Alaska, Collected by Alphonse Louis Pinart, March 20, 1872. Anchorage, Alaska (3212 West 30th Ave., Anchorage 99517-1660): H.J. Simeonoff, 1996.

External links

- Ethnologue report

- The Asiatic (Siberian) Eskimos

- Ludmila Ainana, Tatiana Achirgina-Arsiak, Tasian Tein. Yupik (Asiatic Eskimo). Alaska Native Collections.

- Endangered Languages in Northeast Siberia: Siberian Yupik and other Languages of Chukotka by Nikolai Vakhtin

Old photos:

- Поселок Унгазик (Чаплино) (in Russian). Музея антропологии и этнографии им. Петра Великого (Кунсткамера) Российской академии наук. Rendering in English: Ungazik settlement, Kunstkamera, Russian Academy of Sciences.

- Ungazik settlement. Kunstkamera, Russian Academy of Sciences. Enlarged versions of the above series, select with the navigation arrows or the form.

- Поселок Наукан (in Russian). Музея антропологии и этнографии им. Петра Великого (Кунсткамера) Российской академии наук. Rendering in English: Naukan settlement, Kunstkamera, Russian Academy of Sciences.

- Naukan settlement. Kunstkamera, Russian Academy of Sciences. Enlarged versions of the above series, select with the navigation arrows or the form.

- Chugach Alaska Corporation

- Chugach National Forest

- Ungazik (Chaplino) village Photo-Illustrative Collections of A. S. FORSHTEIN in the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (from the series "Siberia Viewed by Ethnographers. Beginning of XX century")

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.