Pareto, Vilfredo

(copied from Wikipedia) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (43 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Economists]] |

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Sociologists]] |

| − | [[ | + | [[category:biography]] |

| − | [[ | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}} |

| + | {{epname|Pareto, Vilfredo}} | ||

| + | [[Image:Vilfredo Pareto.jpg|right|frame|Vilfredo Pareto.]] | ||

| − | {{ | + | '''Vilfredo Federico Damaso Pareto''', (July 15, 1848 – August 19, 1923) was an [[Italy|Italian]] [[economics|economist]], [[sociology|sociologist]], and [[philosophy|philosopher]]. Trained in [[engineering]], Pareto applied [[mathematics|mathematical]] tools to economic analyses. While he was not effective in promoting his findings during his lifetime, moving on to sociological theorizing, Pareto's work, particularly what was later referred to as the 80-20 principle—that 80 percent of the wealth belongs to 20 percent of the population—has been applied, and found useful, in numerous economic and management situations. Pareto's recognition that human society cannot be understood thoroughly through economic analyses alone, since human beings are not motivated by logic and [[reason]] alone but rather base decisions on [[emotion]]al factors inspired the development of the "behavioralist" school of economic thought. His sociological analyses, however, while intriguing, were unfortunately adopted by [[Benito Mussolini]] in his development of Italian [[fascism]], although Pareto himself supported neither fascism nor [[Marxism]]. |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | ==Biography== | ||

| + | '''Vilfredo Federico Damaso Pareto''' was born on July 15, 1848, in Paris, [[France]]. His father was an [[Italy|Italian]] [[civil engineering|civil engineer]] and his mother was French. | ||

| − | + | In 1870, he gained an [[engineering]] degree from what is now the Polytechnic University of Turin. His thesis was entitled ''The Fundamental Principles of Equilibrium in Solid Bodies''. His later interest in equilibrium analysis in [[economics]] and [[sociology]] can be traced back to this paper. | |

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | For some years after graduation, he worked as a civil engineer, first for the state-owned Italian Railway Company and later in private industry. In 1886, he became a lecturer on economics and management at the University of Florence. In 1893 he was appointed a professor in economics at the University of Lausanne in [[Switzerland]], where he remained for the rest of his life. He died in Lausanne on August 19, 1923. |

| − | == | + | |

| − | + | ==Work== | |

| + | Some [[economics|economists]] put the designation "sociologist" in inverted commas when applied to Pareto, because, while Pareto is often accorded this appellation, it would be truer to say that Pareto is a [[political economy|political economist]] and [[politics|political theorist]]. Nonetheless, his work has important consequences for [[sociology]] and sociologists. His works can be neatly divided into the two areas: [[Vilfredo Pareto#Political Economy|Political Economy]] and [[Vilfredo Pareto#Sociology|Sociology]]. | ||

| − | + | ===Political Economy=== | |

| − | + | Pareto strongly criticized [[Karl Marx]]’s main “doctrine.” In Pareto's view, the Marxist emphasis on the historical struggle between the unpropertied working class—the proletariat—and the [[property]]-owning [[capitalism|capitalist]] class is skewed and terribly misleading. History, he wrote, is indeed full of [[conflict]], but the proletariat-capitalist struggle is merely one of many and by no means the most historically important: | |

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote>''The class struggle, to which Marx has specially drawn attention... is not confined only to two classes: the proletariat and the capitalist; it occurs between an infinite number of groups with different interests, and above all between the elites contending for power.... The oppression of which the proletariat complains, or had cause to complain of, is as nothing in comparison with that which the women of the Australian aborigines suffer. Characteristics to a greater or lesser degree real—nationality, religion, race, language, etc.—may give rise to these groups. In our own day [i.e. 1902] the struggle of the Czechs and the Germans in Bohemia is more intense than that of the proletariat and the capitalists in England'' (Lyttelton, p. 86). </blockquote> | ||

| − | + | Pareto (and his Lausanne School) concentrated on analyzing the relationship between [[demand]] and consumer preferences, between production and the [[profit]]-maximizing behavior of firms. The differential [[calculus]] and Lagrangian multipliers, rather than simple linear systems of equations, were their tools of choice. He replaced all the grand themes of [[Leon Walras]] with a single new one of his own: the efficiency and social optimality of equilibrium. | |

| − | + | ====Pareto's Optimum==== | |

| + | Pareto optimality is a measure of efficiency. An outcome of a [[game theory|game]] is "Pareto optimal" if there is no other outcome that makes every player at least as well off and at least one player strictly better off. That is, a Pareto Optimal outcome cannot be improved upon without hurting at least one player. | ||

| − | + | Much of modern social policy and [[welfare economics]] uses such a formula. If we restate the above definition, it suggests that an optimum allocation of resources is not attained in any given society when it is still possible to make at least one individual better off in his or her own estimation, while keeping others as well off as before in their own estimation (Alexander 1994). | |

| − | + | ====Pareto’s Law and Principle==== | |

| − | + | Pareto did also some investigation of the distribution of income in different economies and concluded that regardless of the ideology the distribution of income is of the negative exponential family, to be illustrated by downward concave curve, i.e. such that rises up quickly from the origin—0-point on the intersection of the horizontal X-axis (where the sample elements: people, countries, etc. are arranged in decreasing order) and vertical Y-axis (where the cumulative percentage of the sample are charted)—to lose its rising-rate as it continues absorbing elements on the X-axis; eventually showing zero increase in the graph. | |

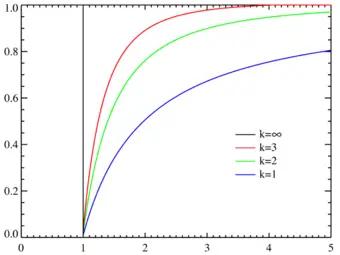

| − | = | + | Constant '''k''' (in the graph) defines various wealth-distribution environments of an investigated country. In an extreme, definitely non-existent, example for '''k = ∞''' (the black vertical line at point 1 on the X-axis in the graph) everybody in the society (country) has exactly the same “wealth.” |

| − | + | On the other side, the area between the red curve at '''k = 3''' and the green curve at '''k = 2''' is, according to Pareto’s claim, probably typical of most countries world-wide then and (surprisingly) even now. At the same time, the blue curve at '''k = 1''' should be the "ideal" of the current and, especially, the future socio-economic environment of the “extremely socially, and cognitively homogeneous society." | |

| − | + | [[Image:Pareto_distributionCDF.png|thumb|340px|Pareto cumulative distribution functions for various values of '''k'''.]] | |

| − | + | To get a feel for Pareto's Law, suppose that in Germany, Japan, Britain, or the USA you count up how many people—that figure goes on the X-axis of the graph, have, say, $10,000. Next, repeat the count for many other values of wealth '''W''' which is on the Y-axis of the graph, both large and small, and finally plot your result. | |

| − | + | You will find that there are only a few extremely rich people. '''Pareto's Law''' says, and it is revealed in the graph, that 20 percent of all the people, these around the point 0.8 (on the X-axis in the graph) own 80 percent of the wealth in all, the then, developed countries; and this has held true until today. Additionally, as the number of “middling-to-poor” people increases, the "wealth" increment gets smaller until the curve parallels the X-axis with no wealth increment at all. | |

| − | Pareto | + | |

| + | Thus, in ''Cours d'économie politique'' (1896, 1897), Pareto's main economic contribution was his exposition of the '''Pareto’s Law''' of income distribution. He argued that in all countries and times (and he studied several of them: [[Italy]], [[England]], [[Germany]], and the [[United States|U. S.]] in great detail), the distribution of income and wealth followed a regular [[logarithm]]ic pattern that can be captured by the formula (that shows the above described graphical quality): | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | '''log N = log A + k log x''', | |

| − | |||

| − | + | where N is the number of income earners who receive incomes higher than x, and A and k are constants. | |

| − | + | Over the years, “Pareto's Law” has proved remarkably resilient in empirical studies and, after his death, was captured and elevated to immortality by the famous '''80-20 Pareto Principle''', which was at the heart of the seventies quality revolution. It suggested, among others, that: | |

| − | + | *80 percent of the output resulted from 20 percent of the input, | |

| + | *80 percent of the consequences flowed from 20 percent of the causes, and | ||

| + | *80 percent of the results came from 20 percent of the effort. | ||

| − | + | ====Other concepts==== | |

| + | Another contribution of the ''Cours'' was Pareto's criticism of the marginal productivity theory of distribution, pointing out that it would fail in situations where there is imperfect [[competition]] or limited substitutability between factors. He repeated his criticisms in many future writings. | ||

| − | + | Pareto was also troubled with the concept of "utility." In its common usage, utility meant the well-being of the individual or society, but Pareto realized that when people make economic decisions, they are guided by what they think is desirable for them, whether or not that corresponds to their well-being. Thus, he introduced the term "ophelimity" to replace the worn-out "utility." | |

| − | Pareto | + | '''Preferences''' were what Pareto was trying to identify (Alexander 1994), noting that human beings are not, for the most part, motivated by [[logic]] and [[reason]] but rather by [[emotion|sentiment]]. This very notion inspired the “behavioralist school” in the U.S. in the 1960s and 1970s (e.g. [[Amos Tversky]], Zvi Grilliches, and [[Daniel Kahneman]] who won the [[Nobel Prize]] for [[Economics]] in 2002). |

| − | + | Pareto reasoned that the field of economics, especially in its modern form, had limited itself to a single aspect of human action: rational or logical action in pursuit of the acquisition of scarce resources. He turned to [[sociology]] when he became convinced that human affairs were largely guided by non-logical, non-rational actions, which were excluded from consideration by the economists. | |

| − | + | ===Sociology=== | |

| − | + | ''Trattato di sociologia generale'', published in 1916, was Pareto's great sociological masterpiece. He explained how human action can be neatly reduced to [[Vilfredo Pareto#Residues|residue]] and [[Vilfredo Pareto#Derivations|derivation]]: people act on the basis of non-logical sentiments (residues) and invent justifications for them afterwards (derivations). | |

| − | Pareto | + | ====Derivations==== |

| + | In Pareto's theory, what he calls '''derivations''' are the ostensibly logical justifications that people employ to rationalize their essentially non-logical, sentiment-driven actions. Pareto names four principle classes of derivations: | ||

| + | #Derivations of assertion; | ||

| + | #derivations of authority; | ||

| + | #derivations that are in agreement with common sentiments and principles; and | ||

| + | #derivations of verbal proof. | ||

| − | + | The first of these include statements of a dogmatic or aphoristic nature; for example, the saying, "honesty is the best policy." The second, authority, is an appeal to people or concepts held in high esteem by [[tradition]]. To cite the opinion of one of the American Founding Fathers on some topic of current interest is to draw from Class II derivations. The third deals with appeals to "universal judgement," the "will of the people," the "best interests of the majority," or similar sentiments. And, finally, the fourth relies on various verbal gymnastics, [[metaphor]]s, [[allegory|allegories]], and so forth. | |

| − | + | The derivation is, thus, just the content and form of the ideology itself. But the residues are the real underlying problem, the particular cause of the squabbles that leads to the "circulation of élites." The underlying residue, he thought, was the only proper object of sociological enquiry. | |

| − | + | ====Residues==== | |

| + | '''Residues''' are non-logical sentiments, rooted in the basic aspirations and drives of people. He identified six classes of residues, all of which are present but unevenly distributed across people—so the population is always a heterogeneous, differentiated mass of different psychological types. | ||

| − | + | The most important residues are Class I, the "instinct for combining" (innovation), and Class II, the "persistence of aggregates" (conservation). Class I types rule by guile, and are calculating, materialistic, and innovating. Class II types rule by force, and are more bureaucratic, idealistic, and conservative. Concerning these two residues, he wrote: "additionally, they are unalterable; man's political nature is not perfectible but remains a constant throughout history” (Pareto 1916). | |

| − | + | For society to function properly there must be a balance between these two types of individuals (Class I and II); the functional relationship between the two is complementary. To illustrate this point, Pareto offered the examples of [[Kaiser Wilhelm I]], his chancellor [[Otto von Bismarck]], and [[Prussia]]'s adversary [[Emperor Napoleon III]]. Wilhelm had an abundance of Class II residues, while Bismarck exemplified Class I. Separately, perhaps, neither would have accomplished much, but together they loomed gigantic in nineteenth-century [[Europe]]an history, each supplying what the other lacked. | |

| − | + | Pareto's theory of society claimed that there was a tendency to return to an equilibrium where a balanced amount of Class I and Class II people are present in the governing élite. People are always entering and leaving the élite, thereby tending to restore the natural balance. On occasion, when it becomes too lopsided, an élite will be replaced en masse by another. | |

| − | + | If there are too many Class I people in the governing élite, this means that violent, conservative Class II's are in the lower echelons, itching and capable of taking power when the Class I's finally brought about ruin by too much cunning and corruption (he regarded Napoleon III's France and the [[Italy|Italian]] "pluto-democratic" system as such an example). If the governing élite is composed mostly of Class II types, then it will fall into a [[bureaucracy|bureaucratic]], inefficient, and reactionary confusion, easy prey for calculating, upwardly-mobile Class I's (e.g. Tsarist [[Russia]]). | |

| − | + | At the social level, according to Pareto's sociological scheme, residues and derivations are mechanisms by which society maintains its equilibrium. Society is seen as a system: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>''a whole consisting of interdependent parts. The 'material points or molecules' of the system ... are individuals who are affected by social forces which are marked by constant or common properties… when imbalances arise, a reaction sets in whereby equilibrium is again achieved'' (Timasheff 1967). </blockquote> | |

| − | + | One of the most intriguing Pareto theories asserts that there are two types of élite within society: the governing élite and the non-governing élite. Moreover, the men who make up these élite strata are of two distinct mentalities, the "speculator" and the "rentier." The speculator is the progressive, filled with Class I residues, while the rentier is the conservative, Class II residue type. There is a natural propensity in healthy societies for the two types to alternate in power. | |

| − | + | When, for example, speculators have devastated the government and outraged the bulk of their countrymen by their corruption and scandals, conservative forces will step to the fore and, in one way or another, replace them. This process is cyclical and more or less inevitable. | |

| − | Pareto | + | Towards the end, even Pareto acknowledged that [[humanitarianism]], [[liberalism]], [[socialism]], [[communism]], [[fascism]], and so forth, were all the same in the end. All ideologies were just "smokescreens" foisted by "leaders" who really only aspired to enjoy the privileges and powers of the governing élite (Alexander 1994). |

| − | + | ==Legacy== | |

| + | Pareto was not effective at promoting the significance of his work in [[economics]], and moved on to develop a series of rambling [[sociology|sociological]] theories. It is worth noting that ''Trattato di Sociologia Generale'' (or ''The Treatise on General Sociology'') first published in English under the title ''Mind and society'', its subsequent theories, and his lectures at the Lausanne University influenced young [[Benito Mussolini]], and thus the development of early [[Italy|Italian]] [[fascism]] (Mussolini 1925, p.14). | ||

| − | Pareto | + | To say that Pareto's economics had a much greater impact would be to ignore the fact that Pareto turned to sociology when he became convinced that human affairs were largely guided by non-logical, non-rational actions, which were excluded from consideration by the economists. For this reason, he attempted in his ''Treatise'' to understand the non-rational aspects of human behavior, omitting almost completely the rational aspects which he considered to be treated adequately in his economic writings. |

| − | " | + | During this “transformation,” Pareto stumbled on the idea that cardinal utility could be dispensed with. "Preferences" were the primitive datum, and utility a mere representation of preference-ordering. With this, Pareto not only inaugurated modern [[microeconomics]], but he also demolished the "unholy alliance" of economics and [[utilitarianism]]. In its stead, he introduced the notion of "Pareto optimality," the idea that a society is enjoying maximum ophelimity when no-one can be made better off without making someone else worse off. Thus, '''Pareto efficiency''', or '''Pareto optimality''', is an important notion in [[economics]], with broad applications in [[game theory]], [[engineering]], and the [[social sciences]] in general. Pareto managed to construct a proper school around himself at Lausanne, including G.B. Antonelli, Boninsegni, Amoroso, and other disciples. Outside this small group, his work also influenced W.E. Johnson, Eugen Slutsky, and Arthur Bowley. |

| − | + | However, Pareto's break-through came posthumously in the 1930s and 1940s, a period which can be called the "Paretian Revival." His "tastes-and-obstacles" approach to demand were resurrected by John Hicks and R.G.D. Allen (1934) and extended and popularized by [[John R. Hicks]] (1939), [[Maurice Allais]] (1943) and [[Paul Samuelson]] (1947). Pareto's work on [[welfare economics]] was resurrected by Harold Hotelling, Oskar Lange and the "New Welfare Economics" movement. | |

| − | Pareto' | + | For practical management, the '''20-80 Pareto principle''' has many important ramifications, including: |

| + | |||

| + | *A manager should focus on the 20 percent that matters. Of the things anybody does during the day, only 20 percent really matter. Those 20 percent produce 80 percent of the entity’s results. One should, therefore, identify and focus on those (relatively few) significant things. | ||

| + | *The principle can be seen as "good news," because re-engineering may need to be apply to only 20 percent of a product range. | ||

| + | *As 80 percent of the increase in wealth from long-term portfolios comes from 20 percent of the [[investment]]s, only the 20 percent have to be analyzed in detail. | ||

| − | + | ==Publications== | |

| − | Principii Fondamentali della Teorie dell' Elasticità | + | *Pareto, V. 1869. ''Principii Fondamentali della Teorie dell' Elasticità''. |

| − | + | *Pareto, V. 1891. "L'Italie économique" in ''Revue des deux mondes''. | |

| − | "L'Italie économique" | + | *Pareto, V. 1892. "Les nouvelles théories économiques" in ''Le monde économique''. |

| − | "Les nouvelles théories économiques" | + | *Pareto, V. 1896-1897. ''Cours d'économie politique professé à l'université de Lausanne''. 3 volumes. |

| − | + | *Pareto, V. 1897. ''The New Theories of Economics''. JPE. | |

| − | + | *Pareto, V. 1900. "Un' Applicazione di teorie sociologiche" in ''Rivista Italiana di Sociologia'' ''(The Rise and Fall of the Elites)''. | |

| − | + | *Pareto, V. 1953 (original 1900). "On the Economic Phenomenon," GdE. | |

| − | + | *Pareto, V. 1901. "Le nuove toerie economiche (con in appendice le equazioni dell' equilibrio dinamico)." GdE. | |

| − | + | *Pareto, V. 1903. "Anwendungen der Mathematik auf Nationalökonomie" in ''Encyklopödie der Mathematischen Wissenschaften''. | |

| − | + | *Pareto, V. 1906. ''Manual of Political Economy''. | |

| − | Cours d'économie politique professé à l'université de Lausanne | + | *Pareto, V. 1907. "L'économie et la sociologie au point de vue scientifique" in ''Rivista di Scienza''. |

| − | + | *Pareto, V. "Economie mathématique" in ''Encyclopedie des sciences mathematiques''. | |

| − | + | *Pareto, V. 1916. ''Trattato di Sociologia Generale'' ''(Treatise on General Sociology)''. | |

| − | "Un' Applicazione di teorie sociologiche" | ||

| − | "On the Economic Phenomenon" | ||

| − | "Le nuove toerie economiche (con in appendice le equazioni dell' equilibrio dinamico)" | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | "Anwendungen der Mathematik auf Nationalökonomie" | ||

| − | |||

| − | Manual of Political Economy , | ||

| − | "L'économie et la sociologie au point de vue scientifique" | ||

| − | "Economie mathématique" | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Trattato di Sociologia Generale | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==References == | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Alexander, J. 1994. "Pareto: Karl Marx of Fascism" in ''Journal of Historical Review''. 14/5, pp. 10-18. | |

| − | * | + | *Allais, Maurice. 1952 (original 1943). ''A La Recherche d'une discipline economique''. |

| − | * | + | *Hicks, John R. 1975 (original 1946). ''Value and Capital''. Clarendon Press, Oxford. ISBN 0198282699 |

| + | *Hicks, John, R. and R. G. D. Allen. 1934. "A Reconsideration of the Theory of Value." in ''Economica''. | ||

| + | *Lyttelton, A. 1973. ''Italian Fascisms: From Pareto to Gentile''. Cape. ISBN 0224008994 | ||

| + | *Mussolini, B. 1928. ''My Autobiography''. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. | ||

| + | *Samuelson, Paul. 1948. "Consumption Theory in Terms of Revealed Preferences" in ''Economica''. vol. 15. | ||

| + | *Timasheff, N. 1967. ''Sociological Theory: Its Nature and Growth''. Random House, New York. | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved May 3, 2023. | |

| − | * [http://www. | + | |

| − | + | *[http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/bios/Pareto.html Vilfredo Pareto (1848-1923)] ''The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics'' | |

| − | {{ | + | |

| + | |||

| + | {{Lausanne economists}} | ||

| + | {{Credits|Vilfredo_Pareto|60223845|Pareto_efficiency|59782040|Pareto_distribution|67113489|}} | ||

Latest revision as of 20:22, 3 May 2023

Vilfredo Federico Damaso Pareto, (July 15, 1848 – August 19, 1923) was an Italian economist, sociologist, and philosopher. Trained in engineering, Pareto applied mathematical tools to economic analyses. While he was not effective in promoting his findings during his lifetime, moving on to sociological theorizing, Pareto's work, particularly what was later referred to as the 80-20 principle—that 80 percent of the wealth belongs to 20 percent of the population—has been applied, and found useful, in numerous economic and management situations. Pareto's recognition that human society cannot be understood thoroughly through economic analyses alone, since human beings are not motivated by logic and reason alone but rather base decisions on emotional factors inspired the development of the "behavioralist" school of economic thought. His sociological analyses, however, while intriguing, were unfortunately adopted by Benito Mussolini in his development of Italian fascism, although Pareto himself supported neither fascism nor Marxism.

Biography

Vilfredo Federico Damaso Pareto was born on July 15, 1848, in Paris, France. His father was an Italian civil engineer and his mother was French.

In 1870, he gained an engineering degree from what is now the Polytechnic University of Turin. His thesis was entitled The Fundamental Principles of Equilibrium in Solid Bodies. His later interest in equilibrium analysis in economics and sociology can be traced back to this paper.

For some years after graduation, he worked as a civil engineer, first for the state-owned Italian Railway Company and later in private industry. In 1886, he became a lecturer on economics and management at the University of Florence. In 1893 he was appointed a professor in economics at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland, where he remained for the rest of his life. He died in Lausanne on August 19, 1923.

Work

Some economists put the designation "sociologist" in inverted commas when applied to Pareto, because, while Pareto is often accorded this appellation, it would be truer to say that Pareto is a political economist and political theorist. Nonetheless, his work has important consequences for sociology and sociologists. His works can be neatly divided into the two areas: Political Economy and Sociology.

Political Economy

Pareto strongly criticized Karl Marx’s main “doctrine.” In Pareto's view, the Marxist emphasis on the historical struggle between the unpropertied working class—the proletariat—and the property-owning capitalist class is skewed and terribly misleading. History, he wrote, is indeed full of conflict, but the proletariat-capitalist struggle is merely one of many and by no means the most historically important:

The class struggle, to which Marx has specially drawn attention... is not confined only to two classes: the proletariat and the capitalist; it occurs between an infinite number of groups with different interests, and above all between the elites contending for power.... The oppression of which the proletariat complains, or had cause to complain of, is as nothing in comparison with that which the women of the Australian aborigines suffer. Characteristics to a greater or lesser degree real—nationality, religion, race, language, etc.—may give rise to these groups. In our own day [i.e. 1902] the struggle of the Czechs and the Germans in Bohemia is more intense than that of the proletariat and the capitalists in England (Lyttelton, p. 86).

Pareto (and his Lausanne School) concentrated on analyzing the relationship between demand and consumer preferences, between production and the profit-maximizing behavior of firms. The differential calculus and Lagrangian multipliers, rather than simple linear systems of equations, were their tools of choice. He replaced all the grand themes of Leon Walras with a single new one of his own: the efficiency and social optimality of equilibrium.

Pareto's Optimum

Pareto optimality is a measure of efficiency. An outcome of a game is "Pareto optimal" if there is no other outcome that makes every player at least as well off and at least one player strictly better off. That is, a Pareto Optimal outcome cannot be improved upon without hurting at least one player.

Much of modern social policy and welfare economics uses such a formula. If we restate the above definition, it suggests that an optimum allocation of resources is not attained in any given society when it is still possible to make at least one individual better off in his or her own estimation, while keeping others as well off as before in their own estimation (Alexander 1994).

Pareto’s Law and Principle

Pareto did also some investigation of the distribution of income in different economies and concluded that regardless of the ideology the distribution of income is of the negative exponential family, to be illustrated by downward concave curve, i.e. such that rises up quickly from the origin—0-point on the intersection of the horizontal X-axis (where the sample elements: people, countries, etc. are arranged in decreasing order) and vertical Y-axis (where the cumulative percentage of the sample are charted)—to lose its rising-rate as it continues absorbing elements on the X-axis; eventually showing zero increase in the graph.

Constant k (in the graph) defines various wealth-distribution environments of an investigated country. In an extreme, definitely non-existent, example for k = ∞ (the black vertical line at point 1 on the X-axis in the graph) everybody in the society (country) has exactly the same “wealth.”

On the other side, the area between the red curve at k = 3 and the green curve at k = 2 is, according to Pareto’s claim, probably typical of most countries world-wide then and (surprisingly) even now. At the same time, the blue curve at k = 1 should be the "ideal" of the current and, especially, the future socio-economic environment of the “extremely socially, and cognitively homogeneous society."

To get a feel for Pareto's Law, suppose that in Germany, Japan, Britain, or the USA you count up how many people—that figure goes on the X-axis of the graph, have, say, $10,000. Next, repeat the count for many other values of wealth W which is on the Y-axis of the graph, both large and small, and finally plot your result.

You will find that there are only a few extremely rich people. Pareto's Law says, and it is revealed in the graph, that 20 percent of all the people, these around the point 0.8 (on the X-axis in the graph) own 80 percent of the wealth in all, the then, developed countries; and this has held true until today. Additionally, as the number of “middling-to-poor” people increases, the "wealth" increment gets smaller until the curve parallels the X-axis with no wealth increment at all.

Thus, in Cours d'économie politique (1896, 1897), Pareto's main economic contribution was his exposition of the Pareto’s Law of income distribution. He argued that in all countries and times (and he studied several of them: Italy, England, Germany, and the U. S. in great detail), the distribution of income and wealth followed a regular logarithmic pattern that can be captured by the formula (that shows the above described graphical quality):

log N = log A + k log x,

where N is the number of income earners who receive incomes higher than x, and A and k are constants.

Over the years, “Pareto's Law” has proved remarkably resilient in empirical studies and, after his death, was captured and elevated to immortality by the famous 80-20 Pareto Principle, which was at the heart of the seventies quality revolution. It suggested, among others, that:

- 80 percent of the output resulted from 20 percent of the input,

- 80 percent of the consequences flowed from 20 percent of the causes, and

- 80 percent of the results came from 20 percent of the effort.

Other concepts

Another contribution of the Cours was Pareto's criticism of the marginal productivity theory of distribution, pointing out that it would fail in situations where there is imperfect competition or limited substitutability between factors. He repeated his criticisms in many future writings.

Pareto was also troubled with the concept of "utility." In its common usage, utility meant the well-being of the individual or society, but Pareto realized that when people make economic decisions, they are guided by what they think is desirable for them, whether or not that corresponds to their well-being. Thus, he introduced the term "ophelimity" to replace the worn-out "utility."

Preferences were what Pareto was trying to identify (Alexander 1994), noting that human beings are not, for the most part, motivated by logic and reason but rather by sentiment. This very notion inspired the “behavioralist school” in the U.S. in the 1960s and 1970s (e.g. Amos Tversky, Zvi Grilliches, and Daniel Kahneman who won the Nobel Prize for Economics in 2002).

Pareto reasoned that the field of economics, especially in its modern form, had limited itself to a single aspect of human action: rational or logical action in pursuit of the acquisition of scarce resources. He turned to sociology when he became convinced that human affairs were largely guided by non-logical, non-rational actions, which were excluded from consideration by the economists.

Sociology

Trattato di sociologia generale, published in 1916, was Pareto's great sociological masterpiece. He explained how human action can be neatly reduced to residue and derivation: people act on the basis of non-logical sentiments (residues) and invent justifications for them afterwards (derivations).

Derivations

In Pareto's theory, what he calls derivations are the ostensibly logical justifications that people employ to rationalize their essentially non-logical, sentiment-driven actions. Pareto names four principle classes of derivations:

- Derivations of assertion;

- derivations of authority;

- derivations that are in agreement with common sentiments and principles; and

- derivations of verbal proof.

The first of these include statements of a dogmatic or aphoristic nature; for example, the saying, "honesty is the best policy." The second, authority, is an appeal to people or concepts held in high esteem by tradition. To cite the opinion of one of the American Founding Fathers on some topic of current interest is to draw from Class II derivations. The third deals with appeals to "universal judgement," the "will of the people," the "best interests of the majority," or similar sentiments. And, finally, the fourth relies on various verbal gymnastics, metaphors, allegories, and so forth.

The derivation is, thus, just the content and form of the ideology itself. But the residues are the real underlying problem, the particular cause of the squabbles that leads to the "circulation of élites." The underlying residue, he thought, was the only proper object of sociological enquiry.

Residues

Residues are non-logical sentiments, rooted in the basic aspirations and drives of people. He identified six classes of residues, all of which are present but unevenly distributed across people—so the population is always a heterogeneous, differentiated mass of different psychological types.

The most important residues are Class I, the "instinct for combining" (innovation), and Class II, the "persistence of aggregates" (conservation). Class I types rule by guile, and are calculating, materialistic, and innovating. Class II types rule by force, and are more bureaucratic, idealistic, and conservative. Concerning these two residues, he wrote: "additionally, they are unalterable; man's political nature is not perfectible but remains a constant throughout history” (Pareto 1916).

For society to function properly there must be a balance between these two types of individuals (Class I and II); the functional relationship between the two is complementary. To illustrate this point, Pareto offered the examples of Kaiser Wilhelm I, his chancellor Otto von Bismarck, and Prussia's adversary Emperor Napoleon III. Wilhelm had an abundance of Class II residues, while Bismarck exemplified Class I. Separately, perhaps, neither would have accomplished much, but together they loomed gigantic in nineteenth-century European history, each supplying what the other lacked.

Pareto's theory of society claimed that there was a tendency to return to an equilibrium where a balanced amount of Class I and Class II people are present in the governing élite. People are always entering and leaving the élite, thereby tending to restore the natural balance. On occasion, when it becomes too lopsided, an élite will be replaced en masse by another.

If there are too many Class I people in the governing élite, this means that violent, conservative Class II's are in the lower echelons, itching and capable of taking power when the Class I's finally brought about ruin by too much cunning and corruption (he regarded Napoleon III's France and the Italian "pluto-democratic" system as such an example). If the governing élite is composed mostly of Class II types, then it will fall into a bureaucratic, inefficient, and reactionary confusion, easy prey for calculating, upwardly-mobile Class I's (e.g. Tsarist Russia).

At the social level, according to Pareto's sociological scheme, residues and derivations are mechanisms by which society maintains its equilibrium. Society is seen as a system:

a whole consisting of interdependent parts. The 'material points or molecules' of the system ... are individuals who are affected by social forces which are marked by constant or common properties… when imbalances arise, a reaction sets in whereby equilibrium is again achieved (Timasheff 1967).

One of the most intriguing Pareto theories asserts that there are two types of élite within society: the governing élite and the non-governing élite. Moreover, the men who make up these élite strata are of two distinct mentalities, the "speculator" and the "rentier." The speculator is the progressive, filled with Class I residues, while the rentier is the conservative, Class II residue type. There is a natural propensity in healthy societies for the two types to alternate in power.

When, for example, speculators have devastated the government and outraged the bulk of their countrymen by their corruption and scandals, conservative forces will step to the fore and, in one way or another, replace them. This process is cyclical and more or less inevitable.

Towards the end, even Pareto acknowledged that humanitarianism, liberalism, socialism, communism, fascism, and so forth, were all the same in the end. All ideologies were just "smokescreens" foisted by "leaders" who really only aspired to enjoy the privileges and powers of the governing élite (Alexander 1994).

Legacy

Pareto was not effective at promoting the significance of his work in economics, and moved on to develop a series of rambling sociological theories. It is worth noting that Trattato di Sociologia Generale (or The Treatise on General Sociology) first published in English under the title Mind and society, its subsequent theories, and his lectures at the Lausanne University influenced young Benito Mussolini, and thus the development of early Italian fascism (Mussolini 1925, p.14).

To say that Pareto's economics had a much greater impact would be to ignore the fact that Pareto turned to sociology when he became convinced that human affairs were largely guided by non-logical, non-rational actions, which were excluded from consideration by the economists. For this reason, he attempted in his Treatise to understand the non-rational aspects of human behavior, omitting almost completely the rational aspects which he considered to be treated adequately in his economic writings.

During this “transformation,” Pareto stumbled on the idea that cardinal utility could be dispensed with. "Preferences" were the primitive datum, and utility a mere representation of preference-ordering. With this, Pareto not only inaugurated modern microeconomics, but he also demolished the "unholy alliance" of economics and utilitarianism. In its stead, he introduced the notion of "Pareto optimality," the idea that a society is enjoying maximum ophelimity when no-one can be made better off without making someone else worse off. Thus, Pareto efficiency, or Pareto optimality, is an important notion in economics, with broad applications in game theory, engineering, and the social sciences in general. Pareto managed to construct a proper school around himself at Lausanne, including G.B. Antonelli, Boninsegni, Amoroso, and other disciples. Outside this small group, his work also influenced W.E. Johnson, Eugen Slutsky, and Arthur Bowley.

However, Pareto's break-through came posthumously in the 1930s and 1940s, a period which can be called the "Paretian Revival." His "tastes-and-obstacles" approach to demand were resurrected by John Hicks and R.G.D. Allen (1934) and extended and popularized by John R. Hicks (1939), Maurice Allais (1943) and Paul Samuelson (1947). Pareto's work on welfare economics was resurrected by Harold Hotelling, Oskar Lange and the "New Welfare Economics" movement.

For practical management, the 20-80 Pareto principle has many important ramifications, including:

- A manager should focus on the 20 percent that matters. Of the things anybody does during the day, only 20 percent really matter. Those 20 percent produce 80 percent of the entity’s results. One should, therefore, identify and focus on those (relatively few) significant things.

- The principle can be seen as "good news," because re-engineering may need to be apply to only 20 percent of a product range.

- As 80 percent of the increase in wealth from long-term portfolios comes from 20 percent of the investments, only the 20 percent have to be analyzed in detail.

Publications

- Pareto, V. 1869. Principii Fondamentali della Teorie dell' Elasticità.

- Pareto, V. 1891. "L'Italie économique" in Revue des deux mondes.

- Pareto, V. 1892. "Les nouvelles théories économiques" in Le monde économique.

- Pareto, V. 1896-1897. Cours d'économie politique professé à l'université de Lausanne. 3 volumes.

- Pareto, V. 1897. The New Theories of Economics. JPE.

- Pareto, V. 1900. "Un' Applicazione di teorie sociologiche" in Rivista Italiana di Sociologia (The Rise and Fall of the Elites).

- Pareto, V. 1953 (original 1900). "On the Economic Phenomenon," GdE.

- Pareto, V. 1901. "Le nuove toerie economiche (con in appendice le equazioni dell' equilibrio dinamico)." GdE.

- Pareto, V. 1903. "Anwendungen der Mathematik auf Nationalökonomie" in Encyklopödie der Mathematischen Wissenschaften.

- Pareto, V. 1906. Manual of Political Economy.

- Pareto, V. 1907. "L'économie et la sociologie au point de vue scientifique" in Rivista di Scienza.

- Pareto, V. "Economie mathématique" in Encyclopedie des sciences mathematiques.

- Pareto, V. 1916. Trattato di Sociologia Generale (Treatise on General Sociology).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alexander, J. 1994. "Pareto: Karl Marx of Fascism" in Journal of Historical Review. 14/5, pp. 10-18.

- Allais, Maurice. 1952 (original 1943). A La Recherche d'une discipline economique.

- Hicks, John R. 1975 (original 1946). Value and Capital. Clarendon Press, Oxford. ISBN 0198282699

- Hicks, John, R. and R. G. D. Allen. 1934. "A Reconsideration of the Theory of Value." in Economica.

- Lyttelton, A. 1973. Italian Fascisms: From Pareto to Gentile. Cape. ISBN 0224008994

- Mussolini, B. 1928. My Autobiography. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York.

- Samuelson, Paul. 1948. "Consumption Theory in Terms of Revealed Preferences" in Economica. vol. 15.

- Timasheff, N. 1967. Sociological Theory: Its Nature and Growth. Random House, New York.

External links

All links retrieved May 3, 2023.

- Vilfredo Pareto (1848-1923) The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.