Stanley Milgram

Stanley Milgram (August 15, 1933 – December 20, 1984) was a social psychologist at Yale University, Harvard University and the City University of New York. While at Harvard, he conducted the small-world experiment (the source of the six degrees of separation concept), and while at Yale, he conducted the Milgram experiment on obedience to authority. He also introduced the concept of familiar strangers.

Although considered one of the most important psychologists of the 20th century, he never took a psychology course as an undergraduate at Queens College, New York, where he earned his Bachelor's degree in political science in 1954. He applied to a Ph.D. program in social psychology at Harvard University and was initially rejected due to lack of psychology background. He was accepted in 1954 after taking six courses in psychology, and graduated with the Ph.D. in 1960. Most likely because of his controversial Milgram Experiment, Milgram was denied tenure at Harvard after becoming an assistant professor there, but instead accepted an offer to become a tenured full professor at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York (Blass, 2004). Milgram had a number of significant influences, including psychologists Solomon Asch and Gordon Allport (Milgram, 1977). Milgram himself influenced other psychologists such as Alan C. Elms, who was his first graduate assistant on the obedience experiment.

In 1984, Milgram died of a heart attack at the age of 51 in the city of his birth, New York. He left behind a widow, Alexandra "Sasha" Milgram, and two children.

Familiar stranger

A familiar stranger is an individual who is recognized from regular activities, but with whom one does not interact. First identified by Stanley Milgram in the 1972 paper The Familiar Stranger: An Aspect of Urban Anonymity, it has become an increasingly popular concept in research about social networks.

Somebody who is seen daily on the train or at the gym, but with whom one does not otherwise communicate, is an example of a familiar stranger. Interestingly, if such individuals meet in an unfamiliar setting, for example while travelling, they are more likely to introduce themselves than would perfect strangers, since they have a background of shared experiences.

The 1972 paper was based on two independent research projects he conducted in 1971, one at CUNY and the other at a train station. Milgram published a second paper on the subject, Frozen World of the Familiar Stranger, in 1974. It appeared in the magazine Psychology Today.

UC Berkeley has adopted the concept as part of a research program titled Familiar Stranger Project at its Intel Research Laboratory.

Obedience to authority

The Milgram experiment was a seminal series of social psychology experiments conducted by Yale University psychologist Stanley Milgram, which measured the willingness of study participants to obey an authority figure who instructed them to perform acts that conflicted with their personal conscience. Milgram first described his research in 1963 in an article published in the Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology,[1] and later discussed his findings in greater depth in his 1974 book, Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View.[2]

The experiments began in July 1961, three months after the start of the trial of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem. Milgram devised the experiments to answer this question: "Could it be that Eichmann and his million accomplices in the Holocaust were just following orders? Could we call them all accomplices?"[3]

Milgram summarized the experiment in his 1974 article, "The Perils of Obedience," writing:

The legal and philosophic aspects of obedience are of enormous importance, but they say very little about how most people behave in concrete situations. I set up a simple experiment at Yale University to test how much pain an ordinary citizen would inflict on another person simply because he was ordered to by an experimental scientist. Stark authority was pitted against the subjects' [participants'] strongest moral imperatives against hurting others, and, with the subjects' [participants'] ears ringing with the screams of the victims, authority won more often than not. The extreme willingness of adults to go to almost any lengths on the command of an authority constitutes the chief finding of the study and the fact most urgently demanding explanation.

Ordinary people, simply doing their jobs, and without any particular hostility on their part, can become agents in a terrible destructive process. Moreover, even when the destructive effects of their work become patently clear, and they are asked to carry out actions incompatible with fundamental standards of morality, relatively few people have the resources needed to resist authority.[4]

The experiment

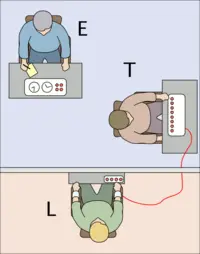

The role of the experimenter was played by a stern, impassive biology teacher dressed in a white technician's coat, and the victim (learner) was played by a 47 year old Irish-American accountant trained to act for the role. The participant and the learner (supposedly another volunteer, but in reality a confederate of the experimenter) were told by the experimenter that they would be participating in an experiment helping his study of memory and learning in different situations.[1]

Two slips of paper were then presented to the participant and to the actor. The participant was led to believe that one of the slips said "learner" and the other said "teacher," and that he and the actor had been given the slips randomly. In fact, both slips said "teacher," but the actor claimed to have the slip that read "learner," thus guaranteeing that the participant would always be the "teacher." At this point, the "teacher" and "learner" were separated into different rooms where they could communicate but not see each other. In one version of the experiment, the confederate was sure to mention to the participant that he had a heart condition.[1]

The "teacher" was given a 45-volt electric shock from the electro-shock generator as a sample of the shock that the "learner" would supposedly receive during the experiment. The "teacher" was then given a list of word pairs which he was to teach the learner. The teacher began by reading the list of word pairs to the learner. The teacher would then read the first word of each pair and read four possible answers. The learner would press a button to indicate his response. If the answer was incorrect, the teacher would administer a shock to the learner, with the voltage increasing for each wrong answer. If correct, the teacher would read the next word pair.[1]

The subjects believed that for each wrong answer, the learner was receiving actual shocks. In reality, there were no shocks. After the confederate was separated from the subject, the confederate set up a tape recorder integrated with the electro-shock generator, which played pre-recorded sounds for each shock level. After a number of voltage level increases, the actor started to bang on the wall that separated him from the subject. After several times banging on the wall and complaining about his heart condition, all responses by the learner would cease.[1]

At this point, many people indicated their desire to stop the experiment and check on the learner. Some test subjects paused at 135 volts and began to question the purpose of the experiment. Most continued after being assured that they would not be held responsible. A few subjects began to laugh nervously or exhibit other signs of extreme stress once they heard the screams of pain coming from the learner.[1]

If at any time the subject indicated his desire to halt the experiment, he was given a succession of verbal prods by the experimenter, in this order:[1]

- Please continue.

- The experiment requires that you continue.

- It is absolutely essential that you continue.

- You have no other choice, you must go on.

If the subject still wished to stop after all four successive verbal prods, the experiment was halted. Otherwise, it was halted after the subject had given the maximum 450-volt shock three times in succession. This experiment could be seen to raise some ethical issues as Stanley Milgram deceived his study's subjects, and put them under more pressure than many believe was necessary.

Results

Before conducting the experiment, Milgram polled fourteen Yale University senior-year psychology majors as to what they thought would be the results. All of the poll respondents believed that only a few (average 1.2%) would be prepared to inflict the maximum voltage. Milgram also informally polled his colleagues and found that they, too, believed very few subjects would progress beyond a very strong shock.[1]

In Milgram's first set of experiments, 65 percent (26 of 40)[1] of experiment participants administered the experiment's final 450-volt shock, though many were very uncomfortable doing so; at some point, every participant paused and questioned the experiment, some said they would refund the money they were paid for participating in the experiment. No participant steadfastly refused to administer shocks before the 300-volt level.[1]

Later, Prof. Milgram and other psychologists performed variations of the experiment throughout the world, with similar results[5] although unlike the Yale experiment, resistance to the experimenter was reported anecdotally elsewhere.[6] Moreover, Milgram later investigated the effect of the experiment's locale on obedience levels, (e.g. one experiment was held in a respectable university, the other in an unregistered, backstreet office in a bustling city; the greater the locale's respectability, the greater the obedience rate). Apart from confirming the original results, the variations have tested variables in the experimental setup.

Dr. Thomas Blass of the University of Maryland Baltimore County performed a meta-analysis on the results of repeated performances of the experiment. He found that the percentage of participants who are prepared to inflict fatal voltages remains remarkably constant, 61–66 percent, regardless of time or place.[7][8][verification needed]

There is a little-known coda to the Milgram Experiment, reported by Philip Zimbardo: None of the participants who refused to administer the final shocks insisted that the experiment itself be terminated, nor left the room to check the health of the victim without requesting permission to leave, per Milgram's notes and recollections, when Zimbardo asked him about that point.[citation needed]

Milgram created a documentary film titled Obedience showing the experiment and its results. He also produced a series of five social psychology films, some of which dealt with his experiments.[9]

The Milgram Experiment raised questions about the ethics of scientific experimentation because of the extreme emotional stress suffered by the participants. In Milgram's defense, 84 percent of former participants surveyed later said they were "glad" or "very glad" to have participated, 15 percent chose neutral responses (92% of all former participants responding).[10] Many later wrote expressing thanks. Milgram repeatedly received offers of assistance and requests to join his staff from former participants. Six years later (at the height of the Vietnam War), one of the participants in the experiment sent correspondence to Milgram, explaining why he was glad to have participated despite the stress:

While I was a subject in 1964, though I believed that I was hurting someone, I was totally unaware of why I was doing so. Few people ever realize when they are acting according to their own beliefs and when they are meekly submitting to authority . . . . To permit myself to be drafted with the understanding that I am submitting to authority's demand to do something very wrong would make me frightened of myself . . . . I am fully prepared to go to jail if I am not granted Conscientious Objector status. Indeed, it is the only course I could take to be faithful to what I believe. My only hope is that members of my board act equally according to their conscience . . . .

The experiments provoked emotional criticism more about the experiment's implications than with experimental ethics. In the journal Jewish Currents, Joseph Dimow, a participant in the 1961 experiment at Yale University, wrote about his early withdrawal as a "teacher," suspicious "that the whole experiment was designed to see if ordinary Americans would obey immoral orders, as many Germans had done during the Nazi period".[11] Indeed, that was one of the explicitly-stated goals of the experiments. Quoting from the preface of Milgram's book, Obedience to Authority: "The question arises as to whether there is any connection between what we have studied in the laboratory and the forms of obedience we so deplored in the Nazi epoch."

In 1981, Tom Peters and Robert H. Waterman Jr wrote that The Milgram Experiment and the later Stanford prison experiment led by Zimbardo at Stanford University were frightening in their implications about the danger lurking in human nature's dark side.[12]

Interpretations

Professor Milgram elaborated two theories explaining his results:

- The first is the theory of conformism, based on Solomon Asch's work, describing the fundamental relationship between the group of reference and the individual person. A subject who has neither ability nor expertise to make decisions, especially in a crisis, will leave decision making to the group and its hierarchy. The group is the person's behavioral model.

- The second is the agentic state theory, wherein, per Milgram, the essence of obedience consists in the fact that a person comes to view himself as the instrument for carrying out another person's wishes, and he therefore no longer sees himself as responsible for his actions. Once this critical shift of viewpoint has occurred in the person, all of the essential features of obedience follow. [citation needed]

Variations

Milgram's variations

In Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View, Milgram describes nineteen variations of his experiment. Generally, when the victim's physical immediacy was increased, the participant's compliance decreased; when the authority's physical immediacy decreased, the participant's compliance decreased (Experiments 1–4). For example, in Experiment 2, where participants received telephonic instructions from the experimenter, compliance decreased to 21 percent; interestingly, some participants deceived the experimenter by pretending to continue the experiment. In the variation where the "learner's" physical immediacy was closest, wherein participants had to physically hold the "learner's" arm onto a shock plate, compliance decreased. Under that condition, 30 percent of participants completed the experiment.

In Experiment 8, women were the participants; previously, all participants had been men. Obedience did not significantly differ, though the women communicated experiencing higher levels of stress.

Experiment 10 took place in a modest office in Bridgeport, Connecticut, purporting to be the commercial entity "Research Associates of Bridgeport" without apparent connection to Yale University, to eliminate the university's prestige as a factor influencing the participants' behavior. In those conditions, obedience dropped to 47.5 percent.

Milgram also combined the power of authority with that of conformity. In those experiments, the participant was joined by one or two additional "teachers" (also actors, like the "learner"). The behavior of the participants' peers strongly affected the results. In Experiment 17, when two additional teachers refused to comply, only 4 of 40 participants continued in the experiment. In Experiment 18, the participant performed a subsidiary task (reading the questions via microphone or recording the learner's answers) with another "teacher" who complied fully. In that variation, only 3 of 40 defied the experimenter.[13]

Replications

Charles Sheridan and Richard King hypothesized that some of Milgram's subjects may have suspected that the victim was faking, so they repeated the experiment with a real victim: a puppy. They found that 20 out of the 26 participants complied to the end. The six who did not were all male; all 13 of the women obeyed to the end, although many were highly disturbed and some openly wept.[14]

Recent variations on Milgram's experiment suggest an interpretation requiring neither obedience nor authority, but suggest that participants suffer learned helplessness, where they feel powerless to control the outcome, and so abdicate their personal responsibility. In a recent experiment using a computer simulation in place of the learner receiving electrical shocks, the participants administering the shocks were aware that the learner was unreal, but still showed the same results.[15]

In the Primetime series Basic Instincts, the Milgram Experiment was repeated in 2006, with the same results with the men; the second experiment, with women, showed they were more likely to continue the experiment. A third experiment, with an additional teacher for peer pressure, showed peer pressure is less likely to stop a participant.[16]

Real life examples

From April 1995 until June 30 2004, there was a series of hoaxes, known as the strip search prank call scam, upon fast food workers in popular fast food chains in America in which a phone caller, claiming to be a police officer, persuaded authority figures to strip and sexually abuse workers. The perpetrator achieved a high level of success in persuading workers to perform acts which they would not have done under normal circumstances.[17] (The chief suspect, David R. Stewart, was found not guilty in the only case that has gone to trial so far.[18])

Media depictions

- The Human Behavior Experiments (2006) is a documentary by Alex Gibney about major experiments in social psychology, shown along with modern incidents highlighting the principles discussed. Along with Stanley Milgram's study in obedience, the documentary shows the 'diffusion of responsibility' study of John Darley and Bibb Latané and the Stanford Prison Experiment of Phillip Zimbardo. [19]

- Another documentary by Alex Gibney, Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room (2005), refers to the Milgram Experiment as the rationale for the actions of Enron's line-level employees. The film was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary.[20]

- The documentary Ghosts of Abu Ghraib, directed by Rory Kennedy, uses actual films clips from the Milgram Experiment.[21] The documentary won an Emmy for Outstanding Non-Fiction Special.[22]

- Obedience is a black-and-white film of the experiment, shot by Milgram himself. It is distributed by The Pennsylvania State University Media Services.

- Atrocity (2005) is a film re-enactment of the Milgram Experiment.[23]

- UK conceptual artist Rod Dickinson recreated one condition of the Milgram obedience experiment as a performance art installation, The Milgram Re-enactment (2002).

- I comme Icare or I as in Icarus (1979), starring French film star Yves Montand is a French political thriller (about the Kennedy assassination) which contains a full and accurate reproduction of Milgram's experiment at a fictitious university meant to remind one of Yale University.

- The Tenth Level (1975) was a CBS television film about the experiment, featuring William Shatner, Ossie Davis, and John Travolta.[24][25]

- The TV show Law & Order: Special Victims Unit used the strip search prank call scam as well as discussion of Milgram's work as the premise for an episode (Season 9, Episode 17).

- Chip Kidd's 2008 novel The Learners features Milgram and his experiment as central to the plot.

In 1963, Milgram submitted the results of his Milgram experiments in the article "Behavioral study of Obedience." In the ensuing controversy that erupted, the APA held up his application for membership for a year because of questions about the ethics of his work, but then granted him full membership. Ten years later, in 1974, Milgram published Obedience to Authority and was awarded the annual social psychology award by the AAAS (mostly for his work over the social aspects of obedience). Inspired in part by the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann, his models were later also used to explain the 1968 My Lai massacre (including authority training in the military, depersonalizing the "enemy" through racial and cultural differences, etc.).

In 1976, CBS presented a made-for-television movie about obedience experiments: The Tenth Level with William Shatner as Stephen Hunter, a Milgram-like scientist. Milgram himself was a consultant for the film, though his personal life did not resemble that of the Shatner character. In this film, incidents were portrayed that never occurred in the followup to the real life experiment, including a subject's psychotic episode and the main character saying that he regretted the experiment. When asked about the film, Milgram told one of his graduate students, Sharon Presley, that he was not happy with the film and told her that he did not want his name to be used in the credits.

A French political thriller, titled I... comme Icare ("I"...as in Icarus), involves a key scene where Milgram's experiment on obedience to authority is explained and shown.

In Alan Moore's graphic novel, V for Vendetta, the character Dr. Delia Surridge discusses Milgram's experiment without directly naming Milgram, comparing it with the atrocities she herself had performed in the Larkhill Concentration camps.

In 1986, musician Peter Gabriel wrote a song called We do what we're told (Milgram's 37), referring to the number of fully obedient participants in Milgram's Experiment 18: A Peer Administers Shocks. In this one, 37 out of 40 participants administered the full range of shocks up to 450 volts, the highest obedience rate Milgram found in his whole series. In this variation, the actual subject did not pull the shock lever; instead he only conveyed information to the peer (a confederate) who pulled the lever. Thus, according to Milgram, the subject shifts responsibility to another person and does not blame himself for what happens. This resembles real-life incidents in which people see themselves as merely cogs in a wheel, just "doing their job," allowing them to avoid responsibility for the consequences of their actions.

The award-winning short film "Atrocity" (2005) re-enacts Milgram's obedience to authority experiment.

Small World Phenomenon

The small world experiment comprised several experiments conducted by Stanley Milgram examining the average path length for social networks of people in the United States. The research was groundbreaking in that it suggested that human society is a small world type network characterized by short path lengths. The experiments are often associated with the phrase "six degrees of separation," although Milgram did not use this term himself.

Guglielmo Marconi's conjectures based on his radio work in the early 20th century, which were articulated in his 1909 Nobel Prize address, may have inspired[citation needed] Hungarian author Frigyes Karinthy to write (among many things) a challenge to find another person through which he could not be connected to by at most five people.[26] This is perhaps the earliest reference to the concept of six degrees of separation, and the search for an answer to the small world problem.

Mathematician Manfred Kochen and political scientist Ithiel de Sola Pool wrote a mathematical manuscript, "Contacts and Influences," while working at the University of Paris in the early 1950s, during a time when Milgram visited and collaborated in their research. Their unpublished manuscript circulated among academics for over 20 years before publication in 1978. It formally articulated the mechanics of social networks, and explored the mathematical consequences of these (including the degree of connectedness). The manuscript left many significant questions about networks unresolved, and one of these was the number of degrees of separation in actual social networks.

Milgram took up the challenge on his return from Paris, leading to the experiments reported in "The Small World Problem" in the popular science journal Psychology Today, with a more rigorous version of the paper appearing in Sociometry two years later. The Psychology Today article generated enormous publicity for the experiments, which are well known today, long after much of the formative work has been forgotten.

Milgram's experiment was conceived in an era when a number of independent threads were converging on the idea that the world is becoming increasingly interconnected. Michael Gurevich had conducted seminal work in his empirical study of the structure of social networks in his MIT doctoral dissertation under de Sola Pool. Mathematician Manfred Kochen, an Austrian who had been involved in Statist urban design, extrapolated these empirical results in a mathematical manuscript, Contacts and Influences, concluding that, in an American-sized population without social structure, "it is practically certain that any two individuals can contact one another by means of at least two intermediaries. In a [socially] structured population it is less likely but still seems probable. And perhaps for the whole world's population, probably only one more bridging individual should be needed." They subsequently constructed Monte Carlo simulations based on Gurevich's data, which recognized that both weak and strong acquaintance links are needed to model social structure. The simulations, running on the primitive computers of 1973, were limited, but still were able to predict that a more realistic three degrees of separation existed across the U.S. population, a value that foreshadowed the findings of Milgrim.

Milgram revisited Gurevich's experiments in acquaintanceship networks when he conducted a highly publicized set of experiments beginning in 1967 at Harvard University. Milgram most famous work is a study of obedience and authority, which is widely known as the Milgram Experiment. Milgram's earlier association with de Solla Pool and Kochen was the likely source of his interest in the increasing interconnectedness among human beings. Gurevich's interviews served as a basis for his small world experiments.

Milgram sought to devise an experiment that could answer the small world problem. This was the same phenomenon articulated by the writer Frigyes Karinthy in the 1920s while documenting a widely circulated belief in Budapest that individuals were separated by six degrees of social contact. This observation, in turn, was loosely based on the seminal demographic work of the Statists who were so influential in the design of Eastern European cities during that period. Mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot, born in Lithuania and having traveled extensively in Eastern Europe, was aware of the Statist rules of thumb, and was also a colleague of de Solla Pool, Kochen and Milgram at the University of Paris during the early 1950s (Kochen brought Mandelbrot to work at the Institute for Advanced Study and later IBM in the U.S.). This circle of researchers was fascinated by the interconnectedness and "social capital" of social networks.

Milgram's study results showed that people in the United States seemed to be connected by approximately three friendship links, on average, without speculating on global linkages; he never actually used the phrase "six degrees of separation." Since the Psychology Today article gave the experiments wide publicity, Milgram, Kochen, and Karinthy all had been incorrectly attributed as the origin of the notion of "six degrees"; the most likely popularizer of the phrase "six degrees of separation" is John Guare, who attributed the value "six" to Marconi.

Milgram's experiment developed out of a desire to learn more about the probability that two randomly selected people would know each other.[27] This is one way of looking at the small world problem. An alternative view of the problem is to imagine the population as a social network and attempt to find the average path length between any two nodes. Milgram's experiment was designed to measure these path lengths by developing a procedure to count the number of ties between any two people.

Basic procedure

- Though the experiment went through several variations, Milgram typically chose individuals in the U.S. cities of Omaha, Nebraska and Wichita, Kansas to be the starting points and Boston, Massachusetts to be the end point of a chain of correspondence. These cities were selected because they represented a great distance in the United States, both socially and geographically.[26]

- Information packets were initially sent to randomly selected individuals in Omaha or Wichita. They included letters, which detailed the study's purpose, and basic information about a target contact person in Boston. It additionally contained a roster on which they could write their own name, as well as business reply cards that were pre-addressed to Harvard.

- Upon receiving the invitation to participate, the recipient was asked whether he or she personally knew the contact person described in the letter. If so, the person was to forward the letter directly to that person. For the purposes of this study, knowing someone "personally" is defined as knowing them on a first-name basis.

- In the more likely case that the person did not personally know the target, then the person was to think of a friend or relative they know personally that is more likely to know the target. They were then directed to sign their name on the roster and forward the packet to that person. A postcard was also mailed to the researchers at Harvard so that they could track the chain's progression toward the target.

- When and if the package eventually reached the contact person in Boston, the researchers could examine the roster to count the number of times it had been forwarded from person to person. Additionally, for packages that never reached the destination, the incoming postcards helped identify the break point in the chain.

Results

Shortly after the experiments began, letters would begin arriving to the targets and the researchers would receive postcards from the respondents. Sometimes the packet would arrive to the target in as few as one or two hops, while some chains were composed of as many as nine or ten links. However, a significant problem was that often people refused to pass the letter forward, and thus the chain never reached its destination. In one case, 232 of the 296 letters never reached the destination.[27]

However, 64 of the letters eventually did reach the target contact. Among these chains, the average path length fell around 5.5 or six. Hence, the researchers concluded that people in the United States are separated by about six people on average. And, although Milgram himself never used the phrase "six degrees of separation," these findings likely contributed to its widespread acceptance.[26]

In an experiment in which 160 letters were mailed out, 24 reached the target in his Sharon, Massachusetts home. Of those 24, 16 were given to the target person by the same person Milgram calls "Mr. Jacobs," a clothing merchant. Of those that reached him at his office, more than half came from two other men.[28]

The researchers used the postcards to qualitatively examine the types of chains that are created. Generally, the package quickly reached a close geographic proximity, but would circle the target almost randomly until it found the target's inner circle of friends.[27] This suggests that participants strongly favored geographic characteristics when choosing an appropriate next person in the chain.

Critiques

There are a number of methodological critiques of the Milgram Experiment, which suggest that the average path length might actually be smaller or larger than Milgram expected. Four such critiques are summarized here:

- The "Six Degrees of Separation" Myth argues that Milgram's study suffers from selection and nonresponse bias due to the way participants were recruited and high non-completion rates. If one assumes a constant portion of non-response for each person in the chain, longer chains will be under-represented because it is more likely that they will encounter an unwilling participant. Hence, Milgram's experiment should under-estimate the true average path length.

- One of the key features of Milgram's methodology is that participants are asked to choose the person they know who is most likely to know the target individual. But in many cases, the participant may be unsure which of their friends is the most likely to know the target. Thus, since the participants of the Milgram experiment do not have a topological map of the social network, they might actually be sending the package further away from the target rather than sending it along the shortest path. This may create a slight bias and over-estimate the average number of ties needed for two random people.

- A description of heterogeneous social networks still remains an open question. Though much research was not done for a number of years, in 1998 Duncan Watts and Steven Strogatz published a breakthrough paper in the journal Nature. Mark Buchanan said, "Their paper touched off a storm of further work across many fields of science" (Nexus, p60, 2002). See Watts' book on the topic: Six Degrees: The Science of a Connected Age.

- It is impossible for the entire human population to be acquainted within six degrees of separation because of the existence of certain populations which have had no contact with people outside their own culture, such as the Sentinelese people of North Sentinel Island. However, according to the current estimates of Sentinelese population of 250, they represent only 0.000000038% of the population. It is still possible that more than 99% of the world's population are connected in this way; there would need to be 66,000,000 such isolated people to represent 1% of the population of the earth.

Influence

The social sciences

The Tipping Point by Malcolm Gladwell, based on articles originally published in The New Yorker,[29] elaborates the "funneling" concept. Gladwell argues that the six-degrees phenomenon is dependent on a few extraordinary people ("connectors") with large networks of contacts and friends: these hubs then mediate the connections between the vast majority of otherwise weakly-connected individuals.

Recent work in the effects of the small world phenomenon on disease transmission, however, have indicated that due to the strongly-connected nature of social networks as a whole, removing these hubs from a population usually has little effect on the average path length through the graph (Barrett et al., 2005).[citation needed]

Mathematicians and actors

Smaller communities, such as mathematicians and actors, have been found to be densely connected by chains of personal or professional associations. Mathematicians have created the Erdős number to describe their distance from Paul Erdős based on shared publications. A similar exercise has been carried out for the actor Kevin Bacon for actors who appeared in movies together — the latter effort informing the game "Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon." There is also the combined Erdős-Bacon number, for actor-mathematicians and mathematician-actors. Players of the popular Asian game Go describe their distance from the great player Honinbo Shusaku by counting their Shusaku number, which counts degrees of separation through the games the players have had.

Current research on the small world problem

The small world question is still a popular research topic today, with many experiments still being conducted. For instance, the Small World Project at Columbia University is currently conducting an email-based version of the same experiment, and has actually found average path lengths of about five on a worldwide scale. However, the critiques that apply to Milgram's experiment largely apply also to this current research.

Network models

In 1998, Duncan J. Watts and Steven H. Strogatz, both in the Department of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics at Cornell University, published the first network model on the small-world phenomenon. They showed that networks from both the natural and man-made world, such as the neural network of C. elegans and power grids, exhibit the small-world property. Watts and Strogatz showed that, beginning with a regular lattice, the addition of a small number of random links reduces the diameter — the longest direct path between any two vertices in the network — from being very long to being very short. The research was originally inspired by Watts' efforts to understand the synchronization of cricket chirps, which show a high degree of coordination over long ranges as though the insects are being guided by an invisible conductor. The mathematical model which Watts and Strogatz developed to explain this phenomenon has since been applied in a wide range of different areas. In Watts' words:[30]

- "I think I've been contacted by someone from just about every field outside of English literature. I've had letters from mathematicians, physicists, biochemists, neurophysiologists, epidemiologists, economists, sociologists; from people in marketing, information systems, civil engineering, and from a business enterprise that uses the concept of the small world for networking purposes on the Internet."

Generally, their model demonstrated the truth in Mark Granovetter's observation that it is "the strength of weak ties" that holds together a social network. Although the specific model has since been generalized by Jon Kleinberg, it remains a canonical case study in the field of complex networks. In network theory, the idea presented in the small-world network model has been explored quite extensively. Indeed, several classic results in random graph theory show that even networks with no real topological structure exhibit the small-world phenomenon, which mathematically is expressed as the diameter of the network growing with the logarithm of the number of nodes (rather than proportional to the number of nodes, as in the case for a lattice). This result similarly maps onto networks with a power-law degree distribution, such as scale-free networks.

In computer science, the small-world phenomenon (although it is not typically called that) is used in the development of secure peer-to-peer protocols, novel routing algorithms for the Internet and ad hoc wireless networks, and search algorithms for communication networks of all kinds.

Milgram's experiment in popular culture

Social networks pervade popular culture in the United States and elsewhere. In particular, the notion of six degrees has become part of the collective consciousness. Social networking websites such as Friendster, MySpace, XING, Orkut, Cyworld, Bebo, Facebook, and others have greatly increased the connectivity of the online space through the application of social networking concepts. The "Six Degrees" Facebook application[31] calculates the number of steps between any two members.

"Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon" is a popular game based upon the notion of six degrees of separation. The website The Oracle of Bacon[32] uses social network data available from the Internet Movie Database to determine the number of links between Kevin Bacon and any other celebrity. One academic variant of the game involves calculating an Erdos Number, a measure of one's closeness to the prolific mathematician, Paul Erdos.

The six degrees of separation concept originates from Milgram's "small world experiment" in 1967 that tracked chains of acquaintances in the United States. In the experiment, Milgram sent several packages to 160 random people living in Omaha, Nebraska, asking them to forward the package to a friend or acquiantance who they thought would bring the package closer to a set final individual, a stockbroker from Boston, Massachusetts.

The letter included this specific condition: "If you do not know the target person on a personal basis, do not try to contact him directly. Instead, mail this folder to a personal acquaintance who is more likely than you to know the target person."

Milgram discovered that the majority of the letters made it to the broker within 5 or 6 "steps."

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Stanley Milgram, "Behavioral Study of Obedience" Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 1963 Oct Vol 67(4) 371-378

- ↑ Stanley Milgram, (1974), Obedience to Authority; An Experimental View. Harpercollins (ISBN 006131983X).

- ↑ Milgram (1974). p. ?

- ↑ Milgram, Stanley. (1974), "The Perils of Obedience". Harper's Magazine. Abridged and adapted from Obedience to Authority.

- ↑ Milgram(1974)

- ↑ Melbourne(1972) A version of the experiment was conducted in the Psychology Department of La Trobe University by Dr Robert Montgomery. One 19-year old female student subject (KG), upon having the experiment explained to her, objected to participating. When asked to reconsider she swore at the experimenter and left the laboratory, despite believing that she had "failed" the project

- ↑ Blass, Thomas. "The Milgram paradigm after 35 years: Some things we now know about obedience to authority," Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 1999, 25, pp. 955-978.

- ↑ Blass, Thomas. (2002), "The Man Who Shocked the World," Psychology Today, 35:(2), Mar/Apr 2002.

- ↑ Milgram films. Accessed 4 October 2006.

- ↑ See Milgram (1974), p. 195

- ↑ Dimow, Joseph. "Resisting Authority: A Personal Account of the Milgram Obedience Experiments", Jewish Currents, January 2004.

- ↑ Peters, Thomas, J.,, Waterman, Robert. H., "In Search of Excellence," 1981. Cf. p.78 and onward.

- ↑ Milgram, old answers. Accessed 4 October 2006.

- ↑ Sheridan, C.L. and King, K.G. (1972) Obedience to authority with an authentic victim, Proceedings of the 80th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association 7: 165-6.

- ↑ Slater M, Antley A, Davison A, et al (2006). A virtual reprise of the Stanley Milgram obedience experiments. PLoS ONE 1: e39.

- ↑ The Science of Evil (HTML). Retrieved on 2007-01-04.

- ↑ Wolfson, Andrew. A hoax most cruel. The Courier-Journal. October 9, 2005.

- ↑ Jury finds Stewart not guilty in McDonald's hoax case. The Courier-Journal. October 31, 2006. [Link dead as of January 5th, 2008]

- ↑ The Human Behavior Experiments at IMDb.com. Accessed 4 October 2006.

- ↑ 78th Academy Awards - Nominees and Winners. Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences.

- ↑ "The documentary is framed by clips from Dr. Stanley Milgram’s infamous “obedience” studies in the 1960s, which showed how easily ordinary, law-abiding citizens could be persuaded to inflict pain on strangers with what they were led to believe were high-voltage electric shocks."Alessandra Stanley (2007-02-22). Abu Ghraib and Its Multiple Failures. New York Times.

- ↑ http://www.emmys.org/awards/2007pt/crtvarts_wrap.php Retrieved 2007-09-16

- ↑ Atrocity.. Retrieved on 2007-03-20.

- ↑ Thomas Blass (March/April 2002). The Man who Shocked the World. Psychology Today.

- ↑ The Tenth Level at the Internet Movie Database. Accessed 4 October 2006.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Barabási, Albert-László. 2003. "Linked: How Everything is Connected to Everything Else and What It Means for Business, Science, and Everyday Life." New York: Plume.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Travers, Jeffrey & Stanley Milgram. 1969. "An Experimental Study of the Small World Problem." Sociometry, Vol. 32, No. 4, pp. 425-443.

- ↑ Gladwell, Malcolm. "The Law of the Few", The Tipping Point. Little Brown, 34-38.

- ↑ Six Degrees of Lois Weisberg

- ↑ From Muhammad Ali to Grandma Rose | Discover | Find Articles at BNET.com

- ↑ http://apps.facebook.com/six_degrees_app

- ↑ The Oracle of Bacon, a small world calculator on the network of film actors

Main publications

- Milgram, Stanley. "The Small World Problem." Psychology Today, May 1967. pp 60 - 67

- Milgram, S. (1974), Obedience to Authority; An Experimental View ISBN 0-06-131983-X

- Milgram, S. (1974), "The Perils of Obedience", Harper's Magazine

- Milgram, S. (1977), The individual in a social world: Essays and experiments / Stanley Milgram. ISBN 0-201-04382-3.

- Abridged and adapted from Obedience to Authority.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Blass, T. (2004). The Man Who Shocked the World: The Life and Legacy of Stanley Milgram. Basic Books. ISBN 0738203998

- Levine, Robert V. "Milgram's Progress", American Scientist, July-August, 2004. Book review of The Man Who Shocked the World

- Miller, Arthur G., (1986). The obedience experiments: A case study of controversy in social science. New York : Praeger.

- Parker, Ian, "Obedience" Granta, Issue 71, Autumn 2000. Includes an interview with one of Milgram's volunteers, and discusses modern interest in, and scepticism about, the experiment.

- Tarnow, Eugen, "Towards the Zero Accident Goal: Assisting the First Officer Monitor and Challenge Captain Errors". Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education and Research, 10(1).

- Wu, William, "Practical Psychology: Compliance: The Milgram Experiment."

External links

- stanleymilgram.com - site maintained by Dr Thomas Blass

- milgramreenactment.org - site documenting Milgram's Obedience to Authority experiment by UK artist Rod Dickinson

- Milgram Page - page documenting Milgram's Obedience to Authority experiment

- 'The Man Who Shocked the World' article in Psychology Today by Thomas Blass

- 'The Man Who Shocked the World' article in BMJ by Raj Persaud

- Pinter & Martin, Stanley Milgram's British publishers

- [1] - link to the short film "Atrocity," which re-enacts the Milgram Experiment

- Guide to the Stanley Milgram Papers, Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library

- Stanley Milgram Redux, TBIYTB - description of a recent iteration of Milgram's experiment at Yale University, published in "The Yale Hippolytic," Jan. 22, 2007.

- Behavioral Study of Obedience - Milgram's journal article describing the experiment in, Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 1963, Vol. 67, No. 4, 371-378

- Synthesis of book A faithful synthesis of "Obedience to Authority" – Stanley Milgram

- A personal account of a participant in the Milgram obedience experiments

- Summary and evaluation of the 1963 obedience experiment

- The Science of Evil from ABC News Primetime

- When Good People Do Evil - Article in the Yale Alumni Magazine by Philip Zimbardo on the 45th anniversary of the Milgram experiment.

- Stanley Milgram, Obedience to Authority (1974) Chapter 1 and Chapter 15

- The Electronic Small World Project (host not found)

- The Small World Experiment - 54 little boxes travelling the world

- Find Satoshi Experiment

- What the Milgram Papers in the Yale Archives Reveal About the Original Small World Study

- Planetary-Scale Views on an Instant-Messaging Network

- Mission of the world - Stuffed animals travelling the world on different missions

- Collective dynamics of small-world networks:

- Theory tested for specific groups:

- The Oracle of Bacon at Virginia

- The Oracle of Baseball

- The Erdős Number Project

- The Oracle of Music

- CoverTrek - linking bands and musicians via cover versions.

- Science Friday: Future of Hubble / Small World Networks

PDF - article published in Defense Acquisition University's journal Defense AT&L, proposes "small world / large tent" social networking model.

PDF - article published in Defense Acquisition University's journal Defense AT&L, proposes "small world / large tent" social networking model.- The Chess Oracle of Kasparov - the theory tested for chess players.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Stanley_Milgram history

- Milgram_experiment history

- Small_world_experiment history

- Familiar_stranger history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.