Difference between revisions of "Russian Provisional Government" - New World Encyclopedia

m (Protected "Russian Provisional Government": Completed ([Edit=Allow only administrators] (indefinite) [Move=Allow only administrators] (indefinite))) |

|||

| (182 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Copyedited}} |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | }} | ||

{{History of Russia}} | {{History of Russia}} | ||

| + | {{Julian calendar}} | ||

| + | The '''Russian Provisional Government''' ({{lang-rus|Временное правительство России|Vremennoye pravitel'stvo Rossii}}) was established immediately following the abdication of [[Nicholas II]]. The intention of the provisional government was the organization of elections to a [[Russian Constituent Assembly]] who would be tasked with writing a new constitution and deciding a new form of government. The Provisional Government was initially composed of the liberal [[Constitutional Democratic Party|Kadet]] coalition led by [[Georgy Lvov|Prince Georgy Lvov]], based on their position within the last Duma. As 1917 drug on and elections kept getting delayed, soldiers and workers in Petersburg became more radicalized. The Kadet led government was replaced by the [[socialism|Socialist]] coalition led by [[Alexander Kerensky]]. The provisional government lasted approximately eight months. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | For most of the life of the Provisional Government, the status of the monarchy remained unresolved. Its status was finally clarified on September 1 [September 14, N.S.], when the [[Russian Republic]] was proclaimed, in a decree signed by Kerensky as Minister-President and Zarudny as Minister of Justice. The republic lasted a scant two months before it was overthrown by the [[Bolsheviks]] in the [[Russian Revolution of 1917|October Revolution]]. | ||

[[File:Kolchak-Kerensky-may1917.jpg|thumb|Alexander Kolchak meeting Kerensky in May 1917]] | [[File:Kolchak-Kerensky-may1917.jpg|thumb|Alexander Kolchak meeting Kerensky in May 1917]] | ||

| − | + | ==Background== | |

| − | + | After the [[1905 Russian Revolution]], Tsar Nicholas was forced into a power-sharing arrangement. A new constitution was passed in 1906, a legislative body, the Duma, was created and a Prime Minister appointed. Nicholas regretted the reforms almost as soon as they were enacted, and they did not serve to modernize Russian society and the economy. The authority of the Tsar's government, already weakened by its participation in [[World War I]], began disintegrating on November 1, 1916. | |

| − | + | Alexander Kerensky, a leader of the Social Revolutionary Party (SRs) and [[Pavel Milyukov]], founder and leader of the Constitutional Democratic Party (Kadets) attacked Prime Minister [[Boris Stürmer]]'s government in the Duma. After the government collapsed Stürmer was succeeded by [[Alexander Trepov]] and then [[Nikolai Golitsyn]], but both were Prime Ministers for only a few weeks. By February, conditions had worsened to the point that the government was ready to collapse. | |

| − | == | + | ===February Revolution=== |

| − | The | + | The main events of the [[February Revolution]] took place in and near Petrograd (present-day [[Saint Petersburg]]), the then-capital of Russia, where long-standing discontent with the monarchy erupted into mass protests against food rationing on February 23 [[Old Style and New Style dates|Old Style]] (8 March [[Old Style and New Style dates|New Style]]). Disaffected soldiers from the city's garrison joined [[Food riot|bread rioters]], primarily [[Women in the Russian Revolution|women]] in bread lines, and industrial strikers on the streets. As more and more troops deserted, and with loyal troops away at the [[Eastern Front (World War I)|Front]], the city fell into chaos. |

| − | + | Revolutionary activity lasted about eight days, involving mass demonstrations and violent armed clashes with police and [[Gendarmerie|gendarmes]], the last loyal forces of the Russian monarchy. On February 27 O.S. (March 12 N.S.) mutinous Russian Army forces sided with the revolutionaries. Three days later Tsar [[Nicholas II of Russia|Nicholas II]] [[abdication|abdicated]], ending [[House of Romanov|Romanov]] dynastic rule and the [[Russian Empire]]. A Russian Provisional Government under Prince [[Georgy Lvov]] replaced the [[Council of Ministers of Russia]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | After Nicholas abdicated, Milyukov announced the committee's decision to offer the Regency to his brother, [[Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich of Russia|Grand Duke Michael]], as the next Tsar.<ref>Harold Whitmore Williams, ''The Spirit of the Russian Revolution/ (v. 9)'' (New Haven, CO: Yale University Library, 2010, (original 1919), ISBN 978-1454633624), 3.</ref> Grand Duke Michael, realizing that there was little support for continuing the autocracy,<ref>Michael Lynch, ''Reaction and Revolution: Russia 1894-1924'', 3rd ed., (London, UK: Hodder Murray, 2005, ISBN 0340885890), 79.</ref> deferred to the election of a [[Russian Constituent Assembly]] to decide the form of the next government. The Provisional Government was designed to set up elections to the Assembly while maintaining essential government services. | |

| − | + | ==Formation== | |

| − | | | + | The Provisional Government was formed in [[Petrograd]] in 1917 by the [[Provisional Committee of the State Duma]]. The [[State Duma (Russian Empire)|State Duma]] was the lower chamber in the Russian parliament established after the [[1905 Russian Revolution|Revolution of 1905]]. It was led first in the new post-Tsarist era by [[Prince Georgy Lvov]] (1861{{endash}}1925) and later by [[Alexander Kerensky]] (1881{{endash}}1970). It replaced the Imperial institution of the [[Council of Ministers of Russia]]. |

| − | |||

| − | |- | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | After the 1917 February Revolution and Tsar Nicholas II's abdication, the Provisional Government's members primarily consisted of former [[State Duma (Russian Empire)|State Duma]] members under [[Nicholas II of Russia|Nicholas II]]'s reign. Its members were mainly members of the [[Constitutional Democratic Party]] (known as the Kadets party), as the Kadets were the only formal political party functioning in the Provisional Government at its conception. The Kadet Party (see [[Constitutional Democratic Party]]), composed mostly of liberal intellectuals, formed the greatest opposition to the tsarist regime leading up to the February Revolution. The Kadets transformed from an opposition force into a role of established leadership, as the former opposition party held most of the power in the new Provisional Government. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Although ideological and political ideas differed wildly throughout the Kadet party's leadership and members, most were moderate democrats. The Kadets and the Provisional Government alike pushed for new policies including the release of political prisoners, a decree of freedom of press, cessation of the [[Okhrana]] (secret police), abolition of the death penalty, and rights for minorities. The Provisional Government and the Kadets also wanted Russia to continue to be involved in [[World War I]], much to the dismay of the Soviets. | |

| − | Public announcement of the formation of the Provisional Government | + | ===Announcement=== |

| − | </ref> The announcement | + | Public announcement of the formation of the Provisional Government was published in ''[[Izvestia]]'' the day after its formation.<ref>Michael Duffy, [http://www.firstworldwar.com/source/firstprovgovt.htm "Announcement of the First Provisional Government, 3 March 1917,"] ''FirstWorldWar.com'', December 29, 2002. Retrieved April 27, 2022.</ref> |

| + | The announcement called for sweeping changes that included: | ||

* Full and immediate amnesty on all issues political and religious, including: terrorist acts, military uprisings, and agrarian crimes etc. | * Full and immediate amnesty on all issues political and religious, including: terrorist acts, military uprisings, and agrarian crimes etc. | ||

* Freedom of word, press, unions, assemblies, and strikes with spread of political freedoms to military servicemen within the restrictions allowed by military-technical conditions. | * Freedom of word, press, unions, assemblies, and strikes with spread of political freedoms to military servicemen within the restrictions allowed by military-technical conditions. | ||

| Line 106: | Line 34: | ||

* Replacement of the police with a public [[militsiya]] and its elected chairmanship subordinated to the local authorities. | * Replacement of the police with a public [[militsiya]] and its elected chairmanship subordinated to the local authorities. | ||

* Elections to the authorities of local self-government on basis of universal, direct, equal, and secret vote. | * Elections to the authorities of local self-government on basis of universal, direct, equal, and secret vote. | ||

| − | * Non-disarmament and non-withdrawal | + | * Non-disarmament and non-withdrawal from Petrograd of the military units participating in the revolution movement. |

* Under preservation of strict discipline in ranks and performing a military service - elimination of all restrictions for soldiers in the use of public rights granted to all other citizens. | * Under preservation of strict discipline in ranks and performing a military service - elimination of all restrictions for soldiers in the use of public rights granted to all other citizens. | ||

| Line 117: | Line 45: | ||

| cabinet_number = 9th | | cabinet_number = 9th | ||

| jurisdiction = [[Russian Republic|Russia]] | | jurisdiction = [[Russian Republic|Russia]] | ||

| − | | flag = | + | | flag = |

| − | |||

| incumbent = | | incumbent = | ||

| − | | image = First Provisional.jpg | + | | image = [[File:First Provisional.jpg|150px]] |

| date_formed = 2 March [15 March, N.S.] 1917 | | date_formed = 2 March [15 March, N.S.] 1917 | ||

| date_dissolved = July 1917 | | date_dissolved = July 1917 | ||

| Line 190: | Line 117: | ||

|[[Ober-Procurator]] of the [[Most Holy Synod]] || [[Vladimir Nikolaevich Lvov|Vladimir Lvov]]|| [[Progressist Party|Progressist]] || March 1917 | |[[Ober-Procurator]] of the [[Most Holy Synod]] || [[Vladimir Nikolaevich Lvov|Vladimir Lvov]]|| [[Progressist Party|Progressist]] || March 1917 | ||

|-Tsars disapproval of the [Nicholas signed tsar] (Russia) intermediate the Minister of justice (II) | |-Tsars disapproval of the [Nicholas signed tsar] (Russia) intermediate the Minister of justice (II) | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | === World recognition === | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! Country !! Date | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | {{flag|United States|1912}} | ||

| + | | 22 March 1917 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | {{flagcountry|United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland}} | ||

| + | | rowspan=3|24 March 1917 | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | {{flagcountry|France}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | {{flagcountry|Kingdom of Italy}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

==April Crisis== | ==April Crisis== | ||

| − | On April 18 (May 1, {{abbrlink|N.S.|New Style}}) 1917 Minister of Foreign Affairs [[Pavel Milyukov]] sent a note to the Allied governments, promising to continue the war to "its glorious conclusion." On April 20-21, 1917 massive demonstrations of workers and soldiers erupted against the continuation of war. Demonstrations demanded the resignation of Milyukov. They were soon met by the counter-demonstrations organized in his support. General [[Lavr Kornilov]], commander of the Petrograd military district, wished to suppress the | + | On April 18 (May 1, {{abbrlink|N.S.|New Style}}) 1917 Minister of Foreign Affairs [[Pavel Milyukov]] sent a note to the Allied governments, promising to continue the war to "its glorious conclusion." On April 20-21, 1917 massive demonstrations of workers and soldiers erupted against the continuation of war. Demonstrations demanded the resignation of Milyukov. They were soon met by the counter-demonstrations organized in his support. General [[Lavr Kornilov]], commander of the Petrograd military district, wished to suppress the disorder, but premier [[Georgy Lvov]] refused to resort to violence. |

The Provisional Government accepted the resignation of Foreign Minister Milyukov and War Minister Guchkov and made a proposal to the Petrograd Soviet to form a coalition government. As a result of negotiations, on April 22, 1917 an agreement was reached and six socialist ministers joined the cabinet. | The Provisional Government accepted the resignation of Foreign Minister Milyukov and War Minister Guchkov and made a proposal to the Petrograd Soviet to form a coalition government. As a result of negotiations, on April 22, 1917 an agreement was reached and six socialist ministers joined the cabinet. | ||

| − | During this period the Provisional Government largely reflected the will of the Soviet, which increasingly meant the will of the [[Bolshevik]]s. Socialist ministers, coming under fire from their left-wing Soviet associates, were compelled to pursue a | + | During this period the Provisional Government largely reflected the will of the Soviet, which increasingly meant the will of the [[Bolshevik]]s. Socialist ministers, coming under fire from their left-wing Soviet associates, were compelled to pursue a policy to appeal to both sides. The Provisional Government was unable to make decisive policy decisions due to political factionalism and a breakdown of state structures.<ref>Alan Kimball, [http://www.uoregon.edu/~kimball/sac.1917.1920.htm "Annotated chronology (notes),"] ''University of Oregon'', November 29, 2004. Retrieved April 27, 2022.Kimball.</ref> |

== Kerensky's June Offensive == | == Kerensky's June Offensive == | ||

| − | + | In the summer of 1917 the liberals persuaded the socialists that the Provisional Government needed to launch an offensive against Germany. Britain and France requested help to take the pressure off their forces in the West. Russia also sought to avoid national humiliation of a defeat in the war. The government agreed that a "successful military offensive" was required to unite the people and restore morale to the Russian army. [[Alexander Kerensky]], Minister for War, embarked on a "whirlwind tour" of the Russian forces at the fronts, giving passionate speeches, calling on troops to act heroically, stating "we revolutionaries, have the right to death." This worked for a time until Kerensky left and the effect on the troops waned.<ref>Anthony Cash, ''The Russian Revolution: A Collection of Contemporary Documents'' (Essex, England: The Book Service Ltd., 1967, ISBN 9781566960601), 62.</ref> | |

| − | In the summer of 1917 | ||

| − | The | + | The June Offensive, which started on June 16, lasted for just three days before falling apart. During the offensive, the rate of desertion was high and soldiers began to mutiny, with some even killing their commanding officers instead of fighting.<ref>Neil Faulkner, ''A People's History of the Russian Revolution'' (London, England: Pluto Press, 2017, ISBN 978-0745399041), 85–86.</ref> |

| − | + | The offensive resulted in the death of thousands of Russian soldiers and great loss of territory. This failed military offensive produced an immediate effect in Petrograd, a spontaneous armed uprising of soldiers and workers known as the [[July Days]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | The offensive resulted in the death of thousands of Russian soldiers and great loss of territory. This failed military offensive produced an immediate effect in Petrograd | ||

==July crisis and second coalition government== | ==July crisis and second coalition government== | ||

| Line 217: | Line 159: | ||

| flag_border = true | | flag_border = true | ||

| incumbent = | | incumbent = | ||

| − | | image = Второе коалиционное Временное правительство России.jpg | + | | image = [[File:Второе коалиционное Временное правительство России.jpg|300px]] |

| date_formed = July 1917 (see [[July Days]]) | | date_formed = July 1917 (see [[July Days]]) | ||

| date_dissolved = 1 September 1917 | | date_dissolved = 1 September 1917 | ||

| Line 243: | Line 185: | ||

On July 2 (July 15 [[Old Style and New Style dates|N.S.]]), in response to the government's compromises with Ukrainian nationalists, the [[Kadet]] members of the cabinet resigned, leaving Prince Lvov's government in disarray.<ref>S. A. Smith, ''Russia in Revolution: An Empire in Crisis, 1890 to 1928'' (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2017, ISBN 978-0198734826), 123.</ref> This prompted further urban demonstrations, as workers demanded "all power to the Soviets."<ref>Orlando Figes, ''A People's Tragedy: A History of the Russian Revolution'' (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 1996, ISBN 0224041622), 423, 431.</ref> | On July 2 (July 15 [[Old Style and New Style dates|N.S.]]), in response to the government's compromises with Ukrainian nationalists, the [[Kadet]] members of the cabinet resigned, leaving Prince Lvov's government in disarray.<ref>S. A. Smith, ''Russia in Revolution: An Empire in Crisis, 1890 to 1928'' (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2017, ISBN 978-0198734826), 123.</ref> This prompted further urban demonstrations, as workers demanded "all power to the Soviets."<ref>Orlando Figes, ''A People's Tragedy: A History of the Russian Revolution'' (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 1996, ISBN 0224041622), 423, 431.</ref> | ||

| − | On the morning of July 3 (July 16), the machine-gun regiment voted in favor of an armed demonstration. The demonstrators planned to march peacefully to the front of the [[Tauride Palace|Tauride palace]] and elect delegates to "present their demands to the Executive Committee of the Soviet." | + | On the morning of July 3 (July 16), the machine-gun regiment voted in favor of an armed demonstration. The demonstrators planned to march peacefully to the front of the [[Tauride Palace|Tauride palace]] and elect delegates to "present their demands to the Executive Committee of the Soviet." The following day, July 4 (July 17), around 20,000 armed sailors from the Kronstadt naval base arrived in [[Saint Petersburg|Petrograd]]. The mass of soldiers and workers then went to the Bolshevik Headquarters to find [[Vladimir Lenin|Lenin]], who addressed the crowd and promised them that, ultimately, all power would go to the Soviets. However, Lenin was rather reluctant about these developments. His speech was uncertain, barely lasting a minute. |

| + | |||

| + | Violence escalated in the streets. The mob looted shops, houses, and attacked well-dressed civilians. Cossacks and [[Constitutional Democratic Party|Kadets]] stationed atop the buildings of [[Liteyny Avenue]] began to fire upon the crowds, causing the marchers to scatter in panic as dozens were killed. | ||

| + | |||

| + | At around 7 pm, soldiers and a group of workers from the Putilov iron plant broke into the palace and, brandishing their rifles, demanded full power to the Soviets. When Socialist Revolutionary Minister Chernov attempted to calm them down, he was taken outside as a hostage until [[Leon Trotsky|Trotsky]] appeared from the Soviet assembly and intervened with a speech praising the “Comrade Kronstadter’s, pride and glory of the Russian revolution.” | ||

| − | The | + | The Menshevik Chairman of the Soviet, Nikoloz (Karlo) Chkheidze, spoke to the demonstrators in an "imperious tone," calmly handing their leader a Soviet manifesto, and ordered them to return home or be condemned as traitors to the revolution; they quickly dispersed. |

| − | + | The Ministry of Justice released leaflets accusing the Bolsheviks of treason on the charge of inciting armed rebellion with German financial support, and published warrants for the arrest of the party's main leaders. Troops cleared the party's Headquarters in the Kshesinskaya Mansion. The mood in the capital turned anti-Bolshevik. Hundreds of Bolsheviks were arrested and known or suspected Bolsheviks were attacked in the streets by Black Hundred elements. | |

| − | + | Trotsky was captured a few days later and imprisoned, while Lenin fled to Finland. Lenin had refused to stand trial for "treason" as he argued that the state was in the hands of a "counter-revolutionary military dictatorship," which was already engaged in a civil war against the [[proletariat]]. Lenin believed that these events were “an episode in the civil war” and described how “all hopes for a peaceful development of the Russian revolution have vanished for good." While the Provisional Government survived the uprising, their pro-war position meant that moderate socialist government leaders lost their credibility among the soldiers and workers.<ref>Faulkner, 85-86.</ref> | |

| − | + | These developments presented the Provisional Government with a new crisis. Prince Lvov and the bourgeois ministers, belonging to the Constitutional Democratic Party resigned, and no cabinet could be formed until the end of the month. | |

| − | + | [[File:Governo provvisorio russo marzo 1917.jpg|thumb|500px|Russian Provisional Government in March 1917]] | |

| − | + | ==Radicalization and splintering== | |

| + | While the Provisional Government lacked enforcement ability, prominent members within the Government encouraged bottom-up rule. Politicians such as Prime Minister [[Georgy Lvov]] favored devolution of power to decentralized organizations. The Provisional Government did not desire the complete decentralization of power, but certain members advocated for more political participation by the masses in the form of grassroots mobilization. | ||

| − | + | The February Revolution was also accompanied by further politicization of the masses. The rise of local organizations, such as trade unions and rural institutions, and the devolution of power within Russian government gave rise to increasing radicalization over the course of 1917. | |

| − | + | Special interest groups also developed throughout 1917. The rise of special interest organizations gave people the means to mobilize and play a role in the democratic process. While groups such as trade unions formed to represent the needs of the working classes, professional organizations were also developed.<ref>Matthew Rendle, "The Officer Corps, Professionalism, And Democracy In The Russian Revolution," ''The Historical Journal'' 51(4), December 2008, 922.</ref> Professional organizations quickly developed a political side to represent member's interests. The political involvement of these groups represents a form of democratic participation as the government listened to such groups when formulating policy. Such interest groups played a negligible role in politics before February 1917 and after October 1917. | |

| − | The | + | While professional special interest groups were on the rise, so too were worker organizations, especially in the cities. Beyond the formation of trade unions, factory committees of workers rapidly developed on the plant level of industrial centers. The factory committees represented the most radical viewpoints of the time period. The Bolsheviks gained their popularity within these institutions. Nonetheless, these committees represented the most democratic element of 1917 Russia. However, this form of democracy differed from and went beyond the political democracy advocated by the liberal intellectual elites and moderate socialists of the Provisional Government. Workers established economic democracy, as employees gained managerial power and direct control over their workplace. Worker self-management became a common practice throughout industrial enterprises.<ref>Sheila Fitzpatrick, ''The Russian Revolution'' 4th. ed. (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2017, ISBN 978-0198806707), 54-55.</ref> As workers became more militant and gained more economic power, they supported the radical Bolshevik party and lifted the Bolsheviks into power in October 1917. |

| − | + | Many urban workers supported the socialist [[Menshevik]] Party while some, though a small minority in February, favored the more radical Bolshevik Party. The Mensheviks often supported the actions of the Provisional Government and believed that the existence of such a government was a necessary step to achieve [[Communism]]. The Bolsheviks violently opposed the Provisional Government and desired a more rapid transition to Communism. In the countryside, political ideology also shifted leftward, with many peasants supporting the Socialist Revolutionary Party (SRs). The SRs advocated a form of agrarian socialism and land policy that the peasantry overwhelmingly supported. For the most part, urban workers supported the Mensheviks and Bolsheviks (with greater numbers supporting the Bolsheviks as 1917 progressed), while the peasants supported the Socialist Revolutionaries. Over the course of 1917, the rapid development and popularity of these leftist parties turned moderate-liberal parties, such as the Kadets, into the more conservative party within both the Provisional Government and the Petrograd Soviet.<ref>Smith, 105–106.</ref> The Provisional Government was more conservative and faced tremendous opposition from the left. | |

| − | + | ==Alexander Kerensky== | |

| + | After the July Days, [[Alexander Kerensky]], a former member of the Fourth Duma and a chairmen of the Soviet Executive Committee, became the Prime Minister of the Provisional Government. He was brought into the Provisional Government as a way to gain support from left-wing parties and the Petrograd Soviet. When Kerensky became Prime Minister, he tried to work with the Soviets. Kerensky was a moderate socialist, who believed that cooperation with the Provisional Government was necessary. A new coalition cabinet, composed mostly of socialists, was formed days later. Kerensky was chosen for his close association with the Soviets, and thought to be in a strong position to lead.<ref>Cash, 62.</ref> | ||

Second coalition: | Second coalition: | ||

| Line 305: | Line 253: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | The problem of the Provisional Government was its inability to enforce and administer their legislative policies. The Provisional Government was unable to make decisive policy decisions due to political factionalism and a breakdown of state structures.<ref> Alan Kimball, [http://www.uoregon.edu/~kimball/sac.1917.1920.htm "Annotated chronology (notes),"] ''University of Oregon'', November 29, 2004. Retrieved April 27, 2022.</ref> Real enforcement power was in the hands of these local institutions and the Soviets. While the Provisional Government retained the formal authority to rule over Russia, the Petrograd Soviet maintained actual power. With its control over the army and the railroads, the Petrograd Soviet had the means to enforce policies.<ref>Rex A. Wade, ''The Russian Revolution, 1917'' (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0521602426), 67.</ref> Institutions that held power in rural areas were quick to implement national laws regarding the peasantry's use of idle land. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This weakness left the government open to strong challenges from both the right and the left. The Provisional Government's chief adversary on the left was the [[Petrograd Soviet]], a [[Communism|Communist]] committee then taking over and ruling Russia's most important port city, which tentatively cooperated with the government at first, but gradually gained control of the [[Imperial Russian Army|Imperial Army]], local factories, and the [[Russian Railway]].<ref>Alexander Kerensky, ''The Catastrophe— Kerensky's Own Story of the Russian Revolution'' (New York, NY: D. Appleton and Company, 1927, ISBN 0527491004, 126.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Unfortunately for Kerensky the result of his courting of the [[Petrograd Soviet]] only served to strengthen the position of the Soviet at the expense of the government. It ushered in a period of "dual power," "an institutional arrangement under which the Provisional Government enjoyed formal authority, but where the Soviet Executive Committee had real power."<ref>Smith, 106.</ref> This sentiment was echoed by Minister of War Alexander Guchkov: "We (the Provisional Government) do not have authority, but only the appearance of authority; the real power lies with the Soviet".<ref>Wade, 57.</ref> The Provisional Government feared the Soviets immense growing power, attempting to appease them as much as possible. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The period of competition for authority would last until late October 1917. The weakness of the Provisional Government is perhaps best reflected in the derisive nickname given to Kerensky: "persuader-in-chief."<ref>Nicholas Riasanovsky, ''A History of Russia'' (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 6th ed., 2000, ISBN 0195121791), 457.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Kornilov affair== | ||

| + | {{main|Kornilov affair}} | ||

| + | When Kerensky became Prime Minister, he made Lavr Kornilov his commander-in-chief of the armed forces. In September 1917 General [[Lavr Kornilov]], the commander-in-chief of the Russian army, attempted a military [[coup d'état]] that became known as the [[Kornilov affair]] <ref>[https://project1917.com/ "1917 Free History,"] ''Yandex Publishing''. Retrieved April 26, 2022.</ref> (August old style). Due to the weakness of the government, there was talk among the elites of bolstering its power by including Kornilov as a military dictator on the side of Kerensky. The extent to which this deal had indeed been accepted by all parties is still unclear, however, when Kornilov's troops approached Petrograd, Kerensky branded them as counter-revolutionaries and demanded their arrest. Kerensky's denunciation had terrible consequences, as his move was seen in the army as a betrayal of Kornilov, making them finally disloyal to the Provisional Government. Kornilov's troops were arrested by the now armed Red Guard, further undermining the government in favor of the Soviet. In order to defend himself and Petrograd, Kerensky provided the Bolsheviks with arms as he had little support from the army. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==End of the Autocracy== | ||

| + | The status of the monarchy still remained unresolved. This was clarified on September 1 [September 14, N.S.], when the [[Russian Republic]] ({{lang|ru|Российская республика}}, ''{{transl|ru|Rossiyskaya respublika}}'') was proclaimed, in a decree signed by Kerensky as Minister-President and Zarudny as Minister of Justice. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Decree read as follows: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <Blockquote> The Coup of General Kornilov is suppressed. But the turmoil that he spread in the ranks of the army and in the country is great. Once again, a great danger threatens the fate of the country and its freedom. Considering it necessary to put an end to the uncertainty in the political system, and keeping in mind the unanimous and enthusiastic recognition of Republican ideas, which affected the Moscow State Conference, the Provisional Government announces that the state system of the Russian state is the republican system and proclaims the Russian Republic. Urgent need for immediate and decisive action to restore the shocked state system has prompted the Provisional Government to pass the power of government to five individuals from its staff, headed by the Prime Minister. The Provisional Government considers its main objective to be the restoration of public order and the fighting efficiency of the armed forces. Believing that only the concentration of all the surviving forces of the country can help the Motherland out of the difficulty in which it now finds itself, the Provisional Government will seek to expand its membership by attracting to its ranks all those who consider the eternal and general interests of the country more important than the short-term and particular needs of certain parties or classes. The Provisional Government has no doubt that it will succeed in this task in the days ahead.<ref>[http://www.prlib.ru/en-us/History/Pages/Item.aspx?itemid=1112 "The Russian Republic Proclaimed,"] ''prlib.ru''. Retrieved April 26, 2022.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

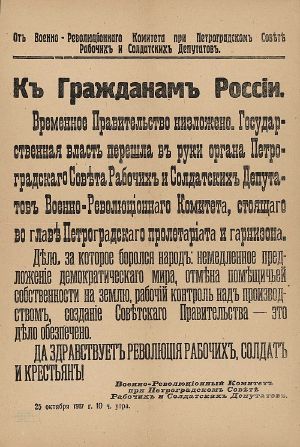

| + | [[File:Milrevkom proclamation.jpg|thumb|[[Milrevcom]] proclamation about the overthrowing of the Provisional Government]] | ||

| + | On September 12 [25, N.S] an All-Russian Democratic Conference was convened, and its presidium decided to create a Pre-Parliament and a [[Russian Constituent Assembly|Special Constituent Assembly]], which was to elaborate the future Constitution of Russia. This Constitutional Assembly was to be chaired by Professor N. I. Lazarev and the historian V. M. Gessen. The Provisional Government was expected to continue to administer Russia until the Constituent Assembly had determined the future form of government, but it would not be long lived. On September 16, 1917, the [[State Duma (Russian Empire)|Duma]] was dissolved by the newly created [[Directorate (Russia)|Directorate]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | From February on, the hope for a democratic Russia hinged on the election of a [[Russian Constituent Assembly|Constituent Assembly]]. Their intention was to create the freest and fairest elections possible, but the challenged that they faced during the course of the year, from their ongoing participation in World War I, to the struggles between the Soviet and the government, and finally the aborted coup attempt rendered the election a moot point. The following month, the Bolsheviks would deliver the final blow.<ref>Mark D. Steinberg, ''The Russian Revolution, 1905 - 1921'' (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2017, ISBN 9780199227624), 72.</ref> | ||

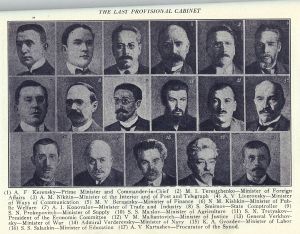

==Third coalition== | ==Third coalition== | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Infobox government cabinet|cabinet_name=Kerensky Second Government|cabinet_number=11th|jurisdiction=[[Russia]]|flag=Flag of Russia.svg|incumbent=|image=[[File:THIRD PROVISIONAL CABINET OF RUSSIA.jpg|300px]]|date_formed=14 September 1917|date_dissolved=7 November 1917|government_head=[[Alexander Kerensky]]|government_head_history=|state_head=[[Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich of Russia|Grand Duke Michael]] (conditionally)<br>[[Alexander Kerensky]] (de facto)|current_number=|former_members_number=|total_number=|political_party=[[Socialist-Revolutionaries]]|legislature_status=[[Coalition government|Coalition]]|opposition_cabinet=[[Petrograd Soviet|Executive Committee of Petrograd Soviet]]|opposition_party=[[Russian Social Democratic Labour Party|RSDLP]]|opposition_leader=[[Nikolay Chkheidze]] / [[Leon Trotsky]]|election=|last_election=|legislature_term=|budget=|incoming_formation=[[Russian Provisional Government#July crisis and second coalition government|Kerensky I]]|outgoing_formation=[[Lenin's First and Second Government|Lenin]]|previous=Alexander Kerensky|successor=[[Vladimir Lenin]]}} |

| − | [[File:THIRD PROVISIONAL CABINET OF RUSSIA.jpg| | + | |

| − | From 25 | + | From September 25 [October 8, N.S.] 1917. |

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 351: | Line 323: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==October Revolution== | ==October Revolution== | ||

{{Main|October Revolution|Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic}} | {{Main|October Revolution|Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic}} | ||

| − | On | + | |

| + | On October 24-26 [[Red Guards (Russia)|Red Guard]] forces under the leadership of Bolshevik commanders launched their final attack on the ineffectual Provisional Government. For the most part, the revolt in Petrograd was bloodless, with the [[Red Guards (Russia)|Red Guards]] led by the Bolsheviks taking over major government facilities with little opposition before finally launching an assault on the [[Winter Palace]] on the night of October 25. The assault led by [[Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko]] was launched at 9:45 p.m., signaled by a blank shot from the cruiser [[Russian cruiser Aurora|''Aurora'']]. The [[Winter Palace]] was guarded by [[Cossack]]s, [[Women's Batallion]], and [[cadet]]s (military students) corps. It was taken at about 2:00 a.m. | ||

| + | Most government offices were occupied and controlled by Bolshevik soldiers on the 25th; the last holdout of the Provisional Ministers, the Tsar's [[Winter Palace]] on the Neva River bank, was captured on the 26th. The insurrection was timed and organized by [[Leon Trotsky]] to hand state power to the Second All-Russian Congress of [[Soviets]] of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies which began on October 26. On October 26, 1917, the [[All-Russian Congress of Soviets]] met and handed power over to a [[Soviet Council of People's Commissars]] with Lenin as chairman, Trotsky as commissar of the [[Red Army]] and minister of foreign affairs, and Bolsheviks taking positions in what was to be the new government. | ||

| − | The Bolsheviks then replaced the government with their own. The ''Little Council'' (or ''Underground Provisional Government'') met at the house of [[Sofia Panina]] briefly in an attempt to resist the Bolsheviks. However, this initiative ended on 28 | + | Kerensky escaped the Winter Palace raid and fled to [[Pskov]], where he rallied some loyal troops for an attempt to retake the capital. His troops managed to capture [[Tsarskoe Selo]] but were beaten the next day at [[Pulkovo Heights|Pulkovo]]. Kerensky spent the next few weeks in hiding before fleeing the country. He went into exile in [[France]] and eventually emigrated to the [[United States]]. |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | The Bolsheviks then replaced the government with their own. The ''Little Council'' (or ''Underground Provisional Government'') met at the house of [[Sofia Panina]] briefly in an attempt to resist the Bolsheviks. However, this initiative ended on November 28 with the arrest of Panina, [[Fyodor Kokoshkin (politician)|Fyodor Kokoshkin]], [[Andrei Ivanovich Shingarev]] and Prince [[Pavel Dolgorukov]].<ref>Adele Lindenmeyr, "The First Soviet Political Trial: Countess Sofia Panina before the Petrograd Revolutionary Tribunal," ''The Russian Review'' 60(4), October 2001, 505–525.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | </ref> | ||

| − | + | ==Legacy== | |

| + | The Provisional Government was a brief and largely unsuccessful attempt to create a democratic government in a country that had never experienced it. Russian historian W.E. Mosse argues that this time period represented "the only time in modern Russian history when the Russian people were able to play a significant part in the shaping of their destinies."<ref>W. E. Mosse, "Interlude: The Russian Provisional Government 1917," Soviet Studies 15 (1964), 414.</ref> Despite its short reign of power and implementation shortcomings, the Provisional Government passed important reforms, including independence of Church from state, the emphasis on rural self-governance, and the affirmation of fundamental civil rights (such as freedom of speech, press, and assembly). Other policies included the abolition of capital punishment and economic redistribution in the countryside. The Provisional Government also granted more freedoms to previously suppressed regions of the Russian Empire. Poland was granted independence and Lithuania and Ukraine became more autonomous.<ref> Mosse, 411-412.</ref> Foreign policy was the one area in which the Provisional Government was able to exercise its discretion to a greater extent. However, the continuation of an aggressive foreign policy, like the [[Kerensky Offensive]]), only increased opposition to the government. | ||

| − | [[Nicholas V. Riasanovsky|Riasanovsky]] argued that the Provisional Government made perhaps its "worst mistake" | + | In the end, the experiment ended in failure. [[Nicholas V. Riasanovsky|Riasanovsky]] argued that the Provisional Government made perhaps its "worst mistake" by not holding elections to the Constituent Assembly soon enough. They wasted time fine-tuning details of the election law, while Russia slipped further into anarchy and economic chaos. By the time the Assembly finally met, Riasanovsky noted, "the Bolsheviks had already gained control of Russia."<ref>Riasanovsky, 457-458.</ref> According to [[Harold Whitmore Williams]] the history of eight months during which Russia was ruled by the Provisional Government was the history of the steady and systematic disorganization of the army.<ref>Harold Whitmore Williams, 14 - 15.</ref> As government institutions collapsed and civil unrest grew, the Provisional Government proved incapable of meeting these challenges effectively. Their failures encouraged Lenin and the Bolsheviks to undertake their coup d'etat that ended the Russian experiment with democracy for over 70 years. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==Notes== |

| − | + | <references/> | |

| − | == | + | ==References== |

| − | + | * Cash, Anthony. ''The Russian Revolution: A Collection of Contemporary Documents''. Essex, England: The Book Service Ltd., 1967. ISBN 978-1566960601 | |

| + | * Faulkner, Neil. ''A People's History of the Russian Revolution''. London, England: Pluto Press, 2017. ISBN 978-0745399041 | ||

| + | * Figes, Orlando. ''A People's Tragedy: A History of the Russian Revolution''. New York, NY: Penguin Books, 1996. ISBN 0224041622 | ||

| + | * Fitzpatrick, Sheila. ''The Russian Revolution'' 4th. ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2017. ISBN 978-0198806707 | ||

| + | * Kerensky, Alexander. ''The Catastrophe— Kerensky's Own Story of the Russian Revolution''. New York, NY: D. Appleton and Company, 1927. ISBN 0527491004 | ||

| + | * Lynch, Michael. ''Reaction and Revolution: Russia 1894-1924'' (3rd ed.). London, UK: Hodder Murray, 2005. ISBN 0340885890 | ||

| + | * Rendle, Matthew. "The Officer Corps, Professionalism, And Democracy In The Russian Revolution," The Historical Journal 51(4), December 2008, 922. | ||

| + | * Riasanovsky, Nicholas. ''A History of Russia''. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 6th ed., 2000. ISBN 0195121791 | ||

| + | * Smith, S. A. ''Russia in Revolution: An Empire in Crisis, 1890 to 1928''. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2017. ISBN 978-0198734826 | ||

| + | * Steinberg, Mark D. ''The Russian Revolution, 1905 - 1921''. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2017. ISBN 9780199227624 | ||

| + | * Wade, Rex A. ''The Russian Revolution, 1917''. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0521602426 | ||

==Further reading== | ==Further reading== | ||

| − | * | + | * Abraham, Richard, ''Kerensky: First Love of the Revolution''. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1987, ISBN 0231061080 |

| − | * Acton, Edward, et al. eds. ''Critical companion to the Russian Revolution, 1914-1921'' | + | * Acton, Edward, et al. eds. ''Critical companion to the Russian Revolution, 1914-1921'' London, UK: Bloomsbury Academic, 2001, ISBN 978-0340763650. |

| − | * Hickey, Michael C. "The Provisional Government and Local Administration in Smolensk in 1917 | + | * Hickey, Michael C. "The Provisional Government and Local Administration in Smolensk in 1917," ''Journal of Modern Russian History and Historiography'' 9(1), 2016, 251–274. |

| − | * Lipatova, Nadezhda V. "On the Verge of the Collapse of Empire: Images of Alexander Kerensky and Mikhail Gorbachev." ''Europe-Asia Studies'' 65 | + | * Lipatova, Nadezhda V. "On the Verge of the Collapse of Empire: Images of Alexander Kerensky and Mikhail Gorbachev." ''Europe-Asia Studies'' 65(2), 2013, 264–289. |

| − | * Orlovsky, Daniel. "Corporatism or democracy: the Russian Provisional Government of 1917 | + | * Orlovsky, Daniel. "Corporatism or democracy: the Russian Provisional Government of 1917," ''The Soviet and Post-Soviet Review'' 24(1), 1997, 15–25. |

| − | * Thatcher, Ian D. "Post-Soviet Russian Historians and the Russian Provisional Government of 1917 | + | * Thatcher, Ian D. "Post-Soviet Russian Historians and the Russian Provisional Government of 1917," ''Slavonic & East European Review'' 93(2), 2015, 315–337. |

| − | * Thatcher, Ian D. "Historiography of the Russian Provisional Government 1917 in the USSR." ''Twentieth Century Communism'' | + | * Thatcher, Ian D. "Historiography of the Russian Provisional Government 1917 in the USSR." ''Twentieth Century Communism'' Issue 8, 2018, 108-132. |

| − | * Thatcher, Ian D. "Memoirs of the Russian Provisional Government 1917." ''Revolutionary Russia'' 27 | + | * Thatcher, Ian D. "Memoirs of the Russian Provisional Government 1917." ''Revolutionary Russia'' 27(1), 2014, 1-21. |

| − | * Thatcher, Ian D. "The ‘broad centrist’ political parties and the first provisional government, 3 March–5 May 1917." ''Revolutionary Russia'' 33 | + | * Thatcher, Ian D. "The ‘broad centrist’ political parties and the first provisional government, 3 March–5 May 1917." ''Revolutionary Russia'' 33(2) 2020, 197-220. |

| − | * Wade, Rex A. "The Revolution at One Hundred: Issues and Trends in the English Language Historiography of the Russian Revolution of 1917." ''Journal of Modern Russian History and Historiography'' 9 | + | * Wade, Rex A. "The Revolution at One Hundred: Issues and Trends in the English Language Historiography of the Russian Revolution of 1917." ''Journal of Modern Russian History and Historiography'' 9(1), 2016, 9-38. |

===Primary sources=== | ===Primary sources=== | ||

| − | * Browder, Robert P. and Alexander F. Kerensky | + | * Browder, Robert P. and Alexander F. Kerensky (eds.). ''The Russian Provisional Government 1917'' 3 vols. Stanford University Press, 1961. ISBN 0804700230 |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{credit|1076503447}} | {{credit|1076503447}} | ||

{{credit|1082010501}} | {{credit|1082010501}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[category: Political science]] | ||

| + | [[category: Politics]] | ||

| + | [[category: History]] | ||

| + | [[category: Government]] | ||

Latest revision as of 22:22, 29 May 2022

| History of Russia |

|---|

| East Slavs |

| Rus' Khaganate |

| Khazars |

| Kievan Rus' |

| Vladimir-Suzdal |

| Novgorod Republic |

| Volga Bulgaria |

| Mongol invasion |

| Golden Horde |

| Muscovy |

| Khanate of Kazan |

| Tsardom of Russia |

Russian Empire

|

Soviet Russia and the USSR

|

| Russian Federation |

The Russian Provisional Government (Russian: Временное правительство России, tr. Vremennoye pravitel'stvo Rossii) was established immediately following the abdication of Nicholas II. The intention of the provisional government was the organization of elections to a Russian Constituent Assembly who would be tasked with writing a new constitution and deciding a new form of government. The Provisional Government was initially composed of the liberal Kadet coalition led by Prince Georgy Lvov, based on their position within the last Duma. As 1917 drug on and elections kept getting delayed, soldiers and workers in Petersburg became more radicalized. The Kadet led government was replaced by the Socialist coalition led by Alexander Kerensky. The provisional government lasted approximately eight months.

For most of the life of the Provisional Government, the status of the monarchy remained unresolved. Its status was finally clarified on September 1 [September 14, N.S.], when the Russian Republic was proclaimed, in a decree signed by Kerensky as Minister-President and Zarudny as Minister of Justice. The republic lasted a scant two months before it was overthrown by the Bolsheviks in the October Revolution.

Background

After the 1905 Russian Revolution, Tsar Nicholas was forced into a power-sharing arrangement. A new constitution was passed in 1906, a legislative body, the Duma, was created and a Prime Minister appointed. Nicholas regretted the reforms almost as soon as they were enacted, and they did not serve to modernize Russian society and the economy. The authority of the Tsar's government, already weakened by its participation in World War I, began disintegrating on November 1, 1916.

Alexander Kerensky, a leader of the Social Revolutionary Party (SRs) and Pavel Milyukov, founder and leader of the Constitutional Democratic Party (Kadets) attacked Prime Minister Boris Stürmer's government in the Duma. After the government collapsed Stürmer was succeeded by Alexander Trepov and then Nikolai Golitsyn, but both were Prime Ministers for only a few weeks. By February, conditions had worsened to the point that the government was ready to collapse.

February Revolution

The main events of the February Revolution took place in and near Petrograd (present-day Saint Petersburg), the then-capital of Russia, where long-standing discontent with the monarchy erupted into mass protests against food rationing on February 23 Old Style (8 March New Style). Disaffected soldiers from the city's garrison joined bread rioters, primarily women in bread lines, and industrial strikers on the streets. As more and more troops deserted, and with loyal troops away at the Front, the city fell into chaos.

Revolutionary activity lasted about eight days, involving mass demonstrations and violent armed clashes with police and gendarmes, the last loyal forces of the Russian monarchy. On February 27 O.S. (March 12 N.S.) mutinous Russian Army forces sided with the revolutionaries. Three days later Tsar Nicholas II abdicated, ending Romanov dynastic rule and the Russian Empire. A Russian Provisional Government under Prince Georgy Lvov replaced the Council of Ministers of Russia.

After Nicholas abdicated, Milyukov announced the committee's decision to offer the Regency to his brother, Grand Duke Michael, as the next Tsar.[1] Grand Duke Michael, realizing that there was little support for continuing the autocracy,[2] deferred to the election of a Russian Constituent Assembly to decide the form of the next government. The Provisional Government was designed to set up elections to the Assembly while maintaining essential government services.

Formation

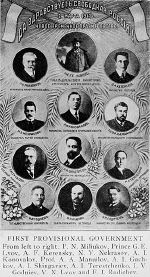

The Provisional Government was formed in Petrograd in 1917 by the Provisional Committee of the State Duma. The State Duma was the lower chamber in the Russian parliament established after the Revolution of 1905. It was led first in the new post-Tsarist era by Prince Georgy Lvov (1861–1925) and later by Alexander Kerensky (1881–1970). It replaced the Imperial institution of the Council of Ministers of Russia.

After the 1917 February Revolution and Tsar Nicholas II's abdication, the Provisional Government's members primarily consisted of former State Duma members under Nicholas II's reign. Its members were mainly members of the Constitutional Democratic Party (known as the Kadets party), as the Kadets were the only formal political party functioning in the Provisional Government at its conception. The Kadet Party (see Constitutional Democratic Party), composed mostly of liberal intellectuals, formed the greatest opposition to the tsarist regime leading up to the February Revolution. The Kadets transformed from an opposition force into a role of established leadership, as the former opposition party held most of the power in the new Provisional Government.

Although ideological and political ideas differed wildly throughout the Kadet party's leadership and members, most were moderate democrats. The Kadets and the Provisional Government alike pushed for new policies including the release of political prisoners, a decree of freedom of press, cessation of the Okhrana (secret police), abolition of the death penalty, and rights for minorities. The Provisional Government and the Kadets also wanted Russia to continue to be involved in World War I, much to the dismay of the Soviets.

Announcement

Public announcement of the formation of the Provisional Government was published in Izvestia the day after its formation.[3] The announcement called for sweeping changes that included:

- Full and immediate amnesty on all issues political and religious, including: terrorist acts, military uprisings, and agrarian crimes etc.

- Freedom of word, press, unions, assemblies, and strikes with spread of political freedoms to military servicemen within the restrictions allowed by military-technical conditions.

- Abolition of all hereditary, religious, and national class restrictions.

- Immediate preparations for the convocation on basis of universal, equal, secret, and direct vote for the Constituent Assembly which will determine the form of government and the constitution.

- Replacement of the police with a public militsiya and its elected chairmanship subordinated to the local authorities.

- Elections to the authorities of local self-government on basis of universal, direct, equal, and secret vote.

- Non-disarmament and non-withdrawal from Petrograd of the military units participating in the revolution movement.

- Under preservation of strict discipline in ranks and performing a military service - elimination of all restrictions for soldiers in the use of public rights granted to all other citizens.

It also said, "The provisional government feels obliged to add that it is not intended to take advantage of military circumstances for any delay in implementing the above reforms and measures."

Initial composition

| Russian Provisional Government | |

| |

| Date Formed | 2 March [15 March, N.S.] 1917 |

|---|---|

| Date Dissolved | July 1917 |

| People and organizations | |

| Head of State | Alexis II (unproclaimed) Michael II (conditionally) |

| Head of government | Georgy Lvov |

| Member party | Progressive Bloc |

| Status in Legislature | Coalition |

| Opposition Cabinet | Executive Committee of Petrograd Soviet |

| Opposition party | Socialist coalition |

| Opposition leader | Nikolay Chkheidze |

| History | |

| Incoming Formation | Golitsyn |

| Outgoing Formation | Kerensky I |

| Predecessor | Nikolay Golitsyn |

| Successor | Alexander Kerensky |

Initial composition of the Provisional Government:

| Post | Name | Party | Time of appointment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prime minister and Minister of the Interior | Georgy Lvov | March 1917 | |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | Pavel Milyukov | Kadet | March 1917 |

| Mikhail Tereshchenko | Non-Party | April 1917 | |

| Minister of War and Navy | Alexander Guchkov | Octobrist | March 1917 |

| Alexander Kerensky | Socialist-Revolutionary Party | April 1917 | |

| Minister of Transport | Nikolai Nekrasov | Kadet | March 1917 |

| Minister of Trade and Industry | Aleksandr Konovalov | Progressist | March 1917 |

| Minister of Justice | Alexander Kerensky | Socialist-Revolutionary Party | March 1917 |

| Pavel Pereverzev | Socialist-Revolutionary Party | April 1917 | |

| Minister of Finance | Mikhail Tereshchenko | Non-Party | March 1917 |

| Andrei Shingarev | Kadet | April 1917 | |

| Minister of Education | Andrei Manuilov | Kadet | March 1917 |

| Minister of Agriculture | Andrei Shingarev | Kadet | March 1917 |

| Victor Chernov | Socialist-Revolutionary Party | April 1917 | |

| Minister of Labour | Matvey Skobelev | Menshevik | April 1917 |

| Minister of Food | Alexey Peshekhonov | Popular Socialists (Russia) | April 1917 |

| Minister of Post and Telegraph | Irakli Tsereteli | Menshevik | April 1917 |

| Ober-Procurator of the Most Holy Synod | Vladimir Lvov | Progressist | March 1917 |

World recognition

| Country | Date |

|---|---|

| 22 March 1917 | |

| 24 March 1917 | |

April Crisis

On April 18 (May 1, N.S.) 1917 Minister of Foreign Affairs Pavel Milyukov sent a note to the Allied governments, promising to continue the war to "its glorious conclusion." On April 20-21, 1917 massive demonstrations of workers and soldiers erupted against the continuation of war. Demonstrations demanded the resignation of Milyukov. They were soon met by the counter-demonstrations organized in his support. General Lavr Kornilov, commander of the Petrograd military district, wished to suppress the disorder, but premier Georgy Lvov refused to resort to violence.

The Provisional Government accepted the resignation of Foreign Minister Milyukov and War Minister Guchkov and made a proposal to the Petrograd Soviet to form a coalition government. As a result of negotiations, on April 22, 1917 an agreement was reached and six socialist ministers joined the cabinet.

During this period the Provisional Government largely reflected the will of the Soviet, which increasingly meant the will of the Bolsheviks. Socialist ministers, coming under fire from their left-wing Soviet associates, were compelled to pursue a policy to appeal to both sides. The Provisional Government was unable to make decisive policy decisions due to political factionalism and a breakdown of state structures.[4]

Kerensky's June Offensive

In the summer of 1917 the liberals persuaded the socialists that the Provisional Government needed to launch an offensive against Germany. Britain and France requested help to take the pressure off their forces in the West. Russia also sought to avoid national humiliation of a defeat in the war. The government agreed that a "successful military offensive" was required to unite the people and restore morale to the Russian army. Alexander Kerensky, Minister for War, embarked on a "whirlwind tour" of the Russian forces at the fronts, giving passionate speeches, calling on troops to act heroically, stating "we revolutionaries, have the right to death." This worked for a time until Kerensky left and the effect on the troops waned.[5]

The June Offensive, which started on June 16, lasted for just three days before falling apart. During the offensive, the rate of desertion was high and soldiers began to mutiny, with some even killing their commanding officers instead of fighting.[6]

The offensive resulted in the death of thousands of Russian soldiers and great loss of territory. This failed military offensive produced an immediate effect in Petrograd, a spontaneous armed uprising of soldiers and workers known as the July Days.

July crisis and second coalition government

| Kerensky First Government | |

| |

| Date Formed | July 1917 (see July Days) |

|---|---|

| Date Dissolved | 1 September 1917 |

| People and organizations | |

| Head of State | Grand Duke Michael (conditionally) Alexander Kerensky (de facto) |

| Head of government | Alexander Kerensky |

| Member party | Socialist Revolutionary Party |

| Status in Legislature | Coalition |

| Opposition Cabinet | Executive Committee of Petrograd Soviet |

| Opposition party | RSDLP |

| Opposition leader | Chkheidze/Trotsky |

| History | |

| Incoming Formation | Lvov |

| Outgoing Formation | Kerensky II |

| Predecessor | Georgy Lvov |

| Successor | Alexander Kerensky |

On July 2 (July 15 N.S.), in response to the government's compromises with Ukrainian nationalists, the Kadet members of the cabinet resigned, leaving Prince Lvov's government in disarray.[7] This prompted further urban demonstrations, as workers demanded "all power to the Soviets."[8]

On the morning of July 3 (July 16), the machine-gun regiment voted in favor of an armed demonstration. The demonstrators planned to march peacefully to the front of the Tauride palace and elect delegates to "present their demands to the Executive Committee of the Soviet." The following day, July 4 (July 17), around 20,000 armed sailors from the Kronstadt naval base arrived in Petrograd. The mass of soldiers and workers then went to the Bolshevik Headquarters to find Lenin, who addressed the crowd and promised them that, ultimately, all power would go to the Soviets. However, Lenin was rather reluctant about these developments. His speech was uncertain, barely lasting a minute.

Violence escalated in the streets. The mob looted shops, houses, and attacked well-dressed civilians. Cossacks and Kadets stationed atop the buildings of Liteyny Avenue began to fire upon the crowds, causing the marchers to scatter in panic as dozens were killed.

At around 7 pm, soldiers and a group of workers from the Putilov iron plant broke into the palace and, brandishing their rifles, demanded full power to the Soviets. When Socialist Revolutionary Minister Chernov attempted to calm them down, he was taken outside as a hostage until Trotsky appeared from the Soviet assembly and intervened with a speech praising the “Comrade Kronstadter’s, pride and glory of the Russian revolution.”

The Menshevik Chairman of the Soviet, Nikoloz (Karlo) Chkheidze, spoke to the demonstrators in an "imperious tone," calmly handing their leader a Soviet manifesto, and ordered them to return home or be condemned as traitors to the revolution; they quickly dispersed.

The Ministry of Justice released leaflets accusing the Bolsheviks of treason on the charge of inciting armed rebellion with German financial support, and published warrants for the arrest of the party's main leaders. Troops cleared the party's Headquarters in the Kshesinskaya Mansion. The mood in the capital turned anti-Bolshevik. Hundreds of Bolsheviks were arrested and known or suspected Bolsheviks were attacked in the streets by Black Hundred elements.

Trotsky was captured a few days later and imprisoned, while Lenin fled to Finland. Lenin had refused to stand trial for "treason" as he argued that the state was in the hands of a "counter-revolutionary military dictatorship," which was already engaged in a civil war against the proletariat. Lenin believed that these events were “an episode in the civil war” and described how “all hopes for a peaceful development of the Russian revolution have vanished for good." While the Provisional Government survived the uprising, their pro-war position meant that moderate socialist government leaders lost their credibility among the soldiers and workers.[9]

These developments presented the Provisional Government with a new crisis. Prince Lvov and the bourgeois ministers, belonging to the Constitutional Democratic Party resigned, and no cabinet could be formed until the end of the month.

Radicalization and splintering

While the Provisional Government lacked enforcement ability, prominent members within the Government encouraged bottom-up rule. Politicians such as Prime Minister Georgy Lvov favored devolution of power to decentralized organizations. The Provisional Government did not desire the complete decentralization of power, but certain members advocated for more political participation by the masses in the form of grassroots mobilization.

The February Revolution was also accompanied by further politicization of the masses. The rise of local organizations, such as trade unions and rural institutions, and the devolution of power within Russian government gave rise to increasing radicalization over the course of 1917.

Special interest groups also developed throughout 1917. The rise of special interest organizations gave people the means to mobilize and play a role in the democratic process. While groups such as trade unions formed to represent the needs of the working classes, professional organizations were also developed.[10] Professional organizations quickly developed a political side to represent member's interests. The political involvement of these groups represents a form of democratic participation as the government listened to such groups when formulating policy. Such interest groups played a negligible role in politics before February 1917 and after October 1917.

While professional special interest groups were on the rise, so too were worker organizations, especially in the cities. Beyond the formation of trade unions, factory committees of workers rapidly developed on the plant level of industrial centers. The factory committees represented the most radical viewpoints of the time period. The Bolsheviks gained their popularity within these institutions. Nonetheless, these committees represented the most democratic element of 1917 Russia. However, this form of democracy differed from and went beyond the political democracy advocated by the liberal intellectual elites and moderate socialists of the Provisional Government. Workers established economic democracy, as employees gained managerial power and direct control over their workplace. Worker self-management became a common practice throughout industrial enterprises.[11] As workers became more militant and gained more economic power, they supported the radical Bolshevik party and lifted the Bolsheviks into power in October 1917.

Many urban workers supported the socialist Menshevik Party while some, though a small minority in February, favored the more radical Bolshevik Party. The Mensheviks often supported the actions of the Provisional Government and believed that the existence of such a government was a necessary step to achieve Communism. The Bolsheviks violently opposed the Provisional Government and desired a more rapid transition to Communism. In the countryside, political ideology also shifted leftward, with many peasants supporting the Socialist Revolutionary Party (SRs). The SRs advocated a form of agrarian socialism and land policy that the peasantry overwhelmingly supported. For the most part, urban workers supported the Mensheviks and Bolsheviks (with greater numbers supporting the Bolsheviks as 1917 progressed), while the peasants supported the Socialist Revolutionaries. Over the course of 1917, the rapid development and popularity of these leftist parties turned moderate-liberal parties, such as the Kadets, into the more conservative party within both the Provisional Government and the Petrograd Soviet.[12] The Provisional Government was more conservative and faced tremendous opposition from the left.

Alexander Kerensky

After the July Days, Alexander Kerensky, a former member of the Fourth Duma and a chairmen of the Soviet Executive Committee, became the Prime Minister of the Provisional Government. He was brought into the Provisional Government as a way to gain support from left-wing parties and the Petrograd Soviet. When Kerensky became Prime Minister, he tried to work with the Soviets. Kerensky was a moderate socialist, who believed that cooperation with the Provisional Government was necessary. A new coalition cabinet, composed mostly of socialists, was formed days later. Kerensky was chosen for his close association with the Soviets, and thought to be in a strong position to lead.[13]

Second coalition:

| Post | Name | Party |

|---|---|---|

| Minister-President and Minister of War and Navy | Alexander Kerensky | Socialist-Revolutionary Party |

| Vice-president, Minister of Finance | Nikolai Nekrasov | Kadet |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | Mikhail Tereshchenko | Non-party |

| Minister of Internal Affairs | Nikolai Avksentiev | Socialist-Revolutionary Party |

| Minister of Transport | Piotr Yurenev | Kadet |

| Minister of the Interior | Irakli Tsereteli | Menshevik |

| Minister of Trade and Industry | Sergei Prokopovich | Non-party |

| Minister of Justice | Alexander Zarudny | Popular Socialists (Russia) |

| Minister of Education | Sergey Oldenburg | Kadet |

| Minister of Agriculture | Victor Chernov | Socialist-Revolutionary Party |

| Minister of Labour | Matvey Skobelev | Menshevik |

| Minister of Food | Alexey Peshekhonov | Popular Socialists (Russia) |

| Minister of Health Care | Ivan Efremov | Progressive Party (Russia) |

| Minister of Post and Telegraph | Alexey Nikitin | Menshevik |

| Ober-Procurator of the Most Holy Synod | Vladimir Lvov | Progressist |

The problem of the Provisional Government was its inability to enforce and administer their legislative policies. The Provisional Government was unable to make decisive policy decisions due to political factionalism and a breakdown of state structures.[14] Real enforcement power was in the hands of these local institutions and the Soviets. While the Provisional Government retained the formal authority to rule over Russia, the Petrograd Soviet maintained actual power. With its control over the army and the railroads, the Petrograd Soviet had the means to enforce policies.[15] Institutions that held power in rural areas were quick to implement national laws regarding the peasantry's use of idle land.

This weakness left the government open to strong challenges from both the right and the left. The Provisional Government's chief adversary on the left was the Petrograd Soviet, a Communist committee then taking over and ruling Russia's most important port city, which tentatively cooperated with the government at first, but gradually gained control of the Imperial Army, local factories, and the Russian Railway.[16]

Unfortunately for Kerensky the result of his courting of the Petrograd Soviet only served to strengthen the position of the Soviet at the expense of the government. It ushered in a period of "dual power," "an institutional arrangement under which the Provisional Government enjoyed formal authority, but where the Soviet Executive Committee had real power."[17] This sentiment was echoed by Minister of War Alexander Guchkov: "We (the Provisional Government) do not have authority, but only the appearance of authority; the real power lies with the Soviet".[18] The Provisional Government feared the Soviets immense growing power, attempting to appease them as much as possible.

The period of competition for authority would last until late October 1917. The weakness of the Provisional Government is perhaps best reflected in the derisive nickname given to Kerensky: "persuader-in-chief."[19]

Kornilov affair

When Kerensky became Prime Minister, he made Lavr Kornilov his commander-in-chief of the armed forces. In September 1917 General Lavr Kornilov, the commander-in-chief of the Russian army, attempted a military coup d'état that became known as the Kornilov affair [20] (August old style). Due to the weakness of the government, there was talk among the elites of bolstering its power by including Kornilov as a military dictator on the side of Kerensky. The extent to which this deal had indeed been accepted by all parties is still unclear, however, when Kornilov's troops approached Petrograd, Kerensky branded them as counter-revolutionaries and demanded their arrest. Kerensky's denunciation had terrible consequences, as his move was seen in the army as a betrayal of Kornilov, making them finally disloyal to the Provisional Government. Kornilov's troops were arrested by the now armed Red Guard, further undermining the government in favor of the Soviet. In order to defend himself and Petrograd, Kerensky provided the Bolsheviks with arms as he had little support from the army.

End of the Autocracy

The status of the monarchy still remained unresolved. This was clarified on September 1 [September 14, N.S.], when the Russian Republic (Российская республика, Rossiyskaya respublika) was proclaimed, in a decree signed by Kerensky as Minister-President and Zarudny as Minister of Justice.

The Decree read as follows:

The Coup of General Kornilov is suppressed. But the turmoil that he spread in the ranks of the army and in the country is great. Once again, a great danger threatens the fate of the country and its freedom. Considering it necessary to put an end to the uncertainty in the political system, and keeping in mind the unanimous and enthusiastic recognition of Republican ideas, which affected the Moscow State Conference, the Provisional Government announces that the state system of the Russian state is the republican system and proclaims the Russian Republic. Urgent need for immediate and decisive action to restore the shocked state system has prompted the Provisional Government to pass the power of government to five individuals from its staff, headed by the Prime Minister. The Provisional Government considers its main objective to be the restoration of public order and the fighting efficiency of the armed forces. Believing that only the concentration of all the surviving forces of the country can help the Motherland out of the difficulty in which it now finds itself, the Provisional Government will seek to expand its membership by attracting to its ranks all those who consider the eternal and general interests of the country more important than the short-term and particular needs of certain parties or classes. The Provisional Government has no doubt that it will succeed in this task in the days ahead.[21]

On September 12 [25, N.S] an All-Russian Democratic Conference was convened, and its presidium decided to create a Pre-Parliament and a Special Constituent Assembly, which was to elaborate the future Constitution of Russia. This Constitutional Assembly was to be chaired by Professor N. I. Lazarev and the historian V. M. Gessen. The Provisional Government was expected to continue to administer Russia until the Constituent Assembly had determined the future form of government, but it would not be long lived. On September 16, 1917, the Duma was dissolved by the newly created Directorate.

From February on, the hope for a democratic Russia hinged on the election of a Constituent Assembly. Their intention was to create the freest and fairest elections possible, but the challenged that they faced during the course of the year, from their ongoing participation in World War I, to the struggles between the Soviet and the government, and finally the aborted coup attempt rendered the election a moot point. The following month, the Bolsheviks would deliver the final blow.[22]

Third coalition

| Kerensky Second Government | |

| |

| Date Formed | 14 September 1917 |

|---|---|

| Date Dissolved | 7 November 1917 |

| People and organizations | |

| Head of State | Grand Duke Michael (conditionally) Alexander Kerensky (de facto) |

| Head of government | Alexander Kerensky |

| Member party | Socialist-Revolutionaries |

| Status in Legislature | Coalition |

| Opposition Cabinet | Executive Committee of Petrograd Soviet |

| Opposition party | RSDLP |

| Opposition leader | Nikolay Chkheidze / Leon Trotsky |

| History | |

| Incoming Formation | Kerensky I |

| Outgoing Formation | Lenin |

| Predecessor | Alexander Kerensky |

| Successor | Vladimir Lenin |

From September 25 [October 8, N.S.] 1917.

| Post | Name | Party |

|---|---|---|

| Minister-President | Alexander Kerensky | Socialist-Revolutionary Party |

| Vice-president, Minister of Trade and Industry | Aleksandr Konovalov | Kadets |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | Mikhail Tereshchenko | Non-party |

| Minister of Internal Affairs, Post and Telegraph | Alexei Nikitin | Menshevik |

| Minister of War | Alexander Verkhovsky | |

| Minister of Navy | Dmitry Verderevsky | – |

| Minister of Finance | Mikhail Bernatsky | |

| Minister of Justice | Pavel Malyantovitch | Menshevik |

| Minister of Transport | Alexander Liverovsky | Non-party |

| Minister of Education | Sergei Salazkin | Non-party |

| Minister of Agriculture | Semen Maslov | Socialist-Revolutionary Party |

| Minister of Labour | Kuzma Gvozdev | Menshevik |

| Minister of Food | Sergei Prokopovich | Non-party |

| Minister of Health Care | Nikolai Kishkin | Kadet |

| Minister of Post and Telegraph | Alexey Nikitin | Menshevik |

| Minister of Religion | Anton Kartashev | Kadet |

| Minister of Public Charities | Nikolai Kishkin | Kadet |

October Revolution