Pavel Milyukov

| Pavel Nikolayevich Milyukov | |

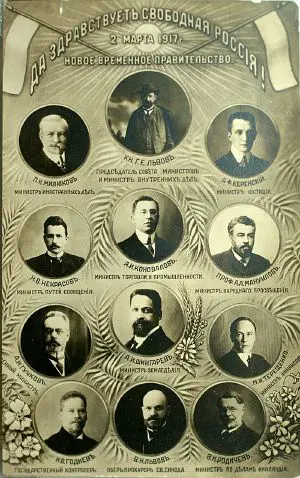

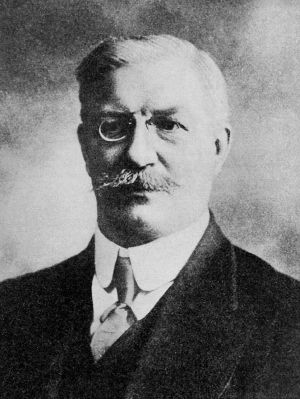

Milyukov in 1916 | |

Member of the Russian Constituent Assembly

| |

| In office November 25, 1917 – January 20, 1918[1] | |

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

|---|---|

| Succeeded by | Constituency abolished |

Minister of Foreign Affairs[2]

| |

| In office March 2 – May 20, 1917 | |

| Prime Minister | Georgy Lvov |

| Preceded by | Nikolai Pokrovsky (for Russian Empire) |

| Succeeded by | Mikhail Tereshchenko |

Member of the Russian State Duma

| |

| In office March–April 1906 – October 6, 1917 | |

| Born | January 27 1859 Moscow, Russian Empire |

| Died | March 31 1943 (aged 84) Aix-les-Bains, Savoie, France |

| Constituency | Petrograd Metropolis |

| Political party | Constitutional Democratic |

| Alma mater | Imperial Moscow University (1882) |

| Occupation | Politician, Author, Historian |

| Signature | |

Pavel Nikolayevich Milyukov is sometimes rendered in English as Paul Miliukov or Paul Milukoff.[3] (Russian: Па́вел Никола́евич Милюко́в, Russian pronunciation: [mʲɪlʲʊˈkof]; January 27 [O.S. January 15] 1859 – March 31 1943) was a Russian historian and liberal politician. Milyukov was the founder, leader, and the most prominent member of the Constitutional Democratic party (known as the Kadets). In the Russian Provisional Government, he served as Foreign Minister, working to prevent Russia's exit from the First World War.

Early life

Pavel was born in Moscow in the upper-class family of Nikolai Pavlovich Milyukov, a professor in architecture who taught at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. Milyukov was a member of the nobility, the House of Milukoff. Milyukov studied history and philology at Moscow University, where he was influenced by Herbert Spencer, Auguste Comte, and Karl Marx. His teachers were Vasily Klyuchevsky and Paul Vinogradoff. In the summer of 1877 he briefly took part in Russo-Turkish War as a military logistics officer, but returned to the university. He was expelled for taking part in student riots, and went to Italy, but was readmitted and allowed to take his degree. He specialized in the study of Russian history and in 1885 received the degree for work on the State Economics of Russia in the First Quarter of the 18th Century and the reforms of Peter the Great.

In 1890 he became a member of the Moscow Society of Russian History and Antiquities. He gave private lectures with great success at a training institute for girl teachers.[4] In 1895 he was appointed to the university. He later expanded these lectures in his book Outlines of Russian Culture (3 vols., 1896–1903, translated into several languages). He started an association for "home university reading," and, as its first president, edited the first volume of its program, which was widely read in Russian intellectual circles. As a student Milyukov was influenced by the liberal ideas of Konstantin Kavelin and Boris Chicherin. His liberal opinions brought him into conflict with the educational authorities, and he was dismissed in 1894 after one of the ever-recurrent university "riots." He was imprisoned for two years in Riazan as a political agitator, but contributed as an archaeologist.

Prerevolutionary career

When released from jail, Milyukov went to Bulgaria, and was appointed professor in the University of Sofia, where he lectured in Bulgarian in the philosophy of history. He was sent to Macedonia (or dismissed under Russian pressure), part of the Ottoman Empire. He worked there in an archaeological site. In 1899 he was allowed to return to St Petersburg. In 1901 he was arrested again for taking part in a commemoration of the populist writer Pyotr Lavrov. (The last volume of Outlines of Russian Culture was actually finished in jail, where he spent six months for his political speech.) In 1901, according to Milyukov, about 16,000 people were exiled from the capital. The following by-law, published in 1902 by the governor of Bessarabia is typical:

Forbidden are all gatherings, meetings, and assemblies on streets, market-places, and other public places, whatever aim they may have. All meetings in private houses for the aim of discussing the statutes of associations for which the permission of the government is necessary are permitted only with the knowledge and approval of the police, who have to give permission for each gathering separately, on an appointed day and in an appointed place.[5]

Activist

He contributed under a pseudonym to the clandestine journal Liberation, founded by Peter Berngardovich Struve, published in Stuttgart in 1902. The government retaliated again, giving him the choice of exile for three years or jail for six months. Milyukov chose the Kresty Prison.[6] After an interview with Vyacheslav von Plehve, whom he regarded as "the symbol of the Russia he hated", Milyukov was released.

In 1903 he delivered courses of lectures in the United States at summer sessions in University of Chicago and for the Lowell Institute lectures in Boston. He visited London and attended the Paris Conference 1904, organized by the Finnish dissident Konni Zilliacus. Milyukov returned to Russia during the Russian Revolution of 1905 which remained unresolved and presaged the conflicts of 1917.[7] He founded the Constitutional Democratic party, a party composed largely of professors, academics, lawyers, writers, journalists, teachers, doctors, officials, and liberal zemstvo men.[8][9]He remained the party leader throughout its existence. Other prominent party members included Peter Struve, future prime minister Prince Georgy Lvov, as well as symbolist poet Konstantin Balmont and composer Igor Stravinsky.

As a journalist for "Svobodny narod" ("Free People") and "Narodnaya swoboda" ("People's Freedom") or as a former political prisoner, Milyukov was not allowed to represent the Kadets in the first and second Duma. For Milyukov any agreement between liberalism and autocracy was impossible.[10] In 1906 the Duma was dissolved and its members moved to Vyborg in Finland. Milyukov drafted the Vyborg Manifesto, calling for political freedom, reforms, and passive resistance to the governmental policy. 120 Kadets signed along with members of other parties.

Dmitri Trepov suggested Ivan Goremykin ought to step down and promote a cabinet with only Kadets, which in his opinion would soon enter into a violent conflict with the Tsar and fail. He secretly met with Milyukov. Trepov opposed Pyotr Stolypin, who promoted a coalition cabinet.[11] The Kadets gave up the idea of founding a republic and promoting a constitutional monarchy. Georgy Lvov and Alexander Guchkov tried to convince the Tsar to accept liberals in the new government.

Milyukov was central in the founding of the Union of Unions in 1905, formed in the wake of Bloody Sunday. The Union of Unions attracted unions of railway workers, bookkeepers and other worker organizations to join and gave the intelligentsia (educated class) a connection with worker organizations.[12] It was an alliance of unions that remained active until the February Revolution, and was one of the precursor organizations to the Petrograd Soviet. He joined the board of the party Rech (newspaper). He was one of the few publicists in Russia, who had considerable knowledge of international politics. His articles on the Near East seem to be of considerable interest.[13]

In January 1908 Milyukov addressed "The Civic Forum" in Carnegie Hall on the issue of the Russian empire.[14] From the very beginning, the slogan and the idea of the empire ruled by Russians were very controversial. It was not clear what "Russians" meant. One of the outspoken critics of the notion, Pavel Milyukov, considered the "Russia for Russians" slogan to have been "a slogan of disunity... [and] not creative but destructive."[15] In 1909, Milyukov addressed the Russian State Duma on the issue of using Ukrainian in the court system, attacking Russian nationalist deputies: "You say "Russia for Russians," but whom do you mean by "Russian"? You should say "Russia only for the Great Russians," because that which you do not give to Muslims and Jews you also do not give your own nearest kin – Ukraine."[16]

Deputy

Milyukov was offered a position in Sergei Witte's first cabinet along with other members of the Kadets, but they were skeptical of its chances to succeed and refused it. In 1907 Milyukov was elected in the Third Duma. In 1912 he was reelected in the Fourth Duma. According to Milyukov, in May 1914 Rasputin had become an influential factor in Russian politics.[17] With the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, Milyukov swung to the right. He embraced a nationalist, patriotic policy of national defense, relying on social chauvinism. (He was best friends with Foreign Minister Sergei Sazonov.) Milyukov insisted his younger son (who subsequently died in battle) volunteer for the army. In August 1915 he formed the Progressive Bloc and became the leader. Milyukov was regarded as a staunch supporter of the conquest of Constantinople. In the nineties, Milyukov had thoroughly studied the Balkans, which made him the most competent authority on Balkan politics.[18] His opponents mockingly called him "Milyukov of the Dardanelles." In Summer 1916, at the request of Rodzianko, Protopopov led a delegation of Duma members (with Milyukov) to strengthen the ties with Russia's western allies in World War I, the (Entente powers).[19] In August he gave lectures in Oxford. On November 1, 1916, in a populist speech, he sharply criticized the Stürmer government for its inefficiency. He met professor Thomas Masaryk in London, and consulted with him about the present state of the Czechoslovak Legion in Russia at that time.[20]

"Stupidity or treason" speech

At Progressive Bloc meetings near the end of October, Progressives and left-Kadets argued that the revolutionary public mood could no longer be ignored and that the Duma should attack the entire tsarist system or lose whatever influence it had. Nationalists feared that a concerted stand against the government would jeopardize the existence of the Duma and further inflame the revolutionary feelings. Miliukov argued for and secured a tenuous adherence to a middle-ground tactic, attacking Boris Stürmer and forcing his replacement.

According to Stockdale, he had trouble gaining the support of his own party. At the October 22-24 Kadet fall conference, provincial delegates "lashed out at Miliukov with unaccustomed ferocity. His travels abroad had made him poorly informed about the public mood, they charged; the patience of the people was exhausted." He responded with a plea to keep their ultimate goal in mind:

It will be our task not to destroy the government, which would only aid anarchy, but to instill in it a completely different content, that is, to build a genuine constitutional order. That is why, in our struggle with the government, despite everything, we must retain a sense of proportion... To support anarchy in the name of the struggle with the government would be to risk all the political conquests we have made since 1905.[22]

The day before the opening of the Duma, the Progressist party pulled out of the bloc because they believed the situation called for more than a mere denunciation of Stürmer.

On November 1 (O.S.) the government under the pro-peace Boris Stürmer was attacked in the Imperial Duma, which had not met since February.[23] Alexander Kerensky spoke first, called the ministers "hired assassins" and "cowards" and said they were "guided by the contemptible Grishka [or Grigori] Rasputin!."[24] The acting president Rodzianko ordered him to leave for calling for the overthrow of the government in wartime.[24] Miliukov's speech was more than three times longer than Kerensky's, and delivered using much more moderate language.

In his speech "Rasputin and Rasputuiza" he spoke of "treachery and betrayal, about the dark forces, fighting in favor of Germany."[25] He highlighted numerous governmental failures, including the case Sukhomlinov, concluding that Stürmer's policies placed in jeopardy the Triple Entente. After each accusation – many times without basis – he asked "Is this stupidity or is it treason?" and the listeners responded with either "stupidity!," or "treason!." (Milyukov stated that it did not matter "Choose any ... as the consequences are the same.") Stürmer walked out, followed by all his ministers.[26]

He began by outlining how public hope had been lost over the course of the war, saying: "We have lost faith that the government can lead us to victory." He mentioned the rumors of treason and then proceeded to discuss some of the allegations: that Stürmer had freed Suchomlinov, that there was a great deal of pro-German propaganda, that he had been told that the enemy had access to Russian state secrets in his visits to allied countries and that Stürmer's private secretary, Ivan Manuilov-Manasevich, had been arrested for taking German bribes but was released when he kicked back to Stürmer.

Milyukov was taken immediately by Sir George Buchanan to the British Embassy and lived there till the February Revolution;[27] (although according to Stockdale he went to the Crimea). It is not known what they discussed, but his speech was spread in flyers on the front and at the Hinterland. Stürmer and Protopopov asked in vain for the dissolution of the Duma.[28] Tsarina Alexandra suggested to her husband to expel Alexander Guchkov, Prince Lvov, Milyukov and Alexei Polivanov to Siberia.[29]

According to Melissa Kirschke Stockdale, it was a "volatile combination of revolutionary passions, escalating apprehension, and the near breakdown of unity in the moderate camp that provided the impetus for the most notorious address in the history of the Duma..." The speech was a milestone on the road to Rasputin's murder and the February Revolution. Stockdale also points out that Milyukov admitted to some reservations about his evidence in his memoirs, where he observed that his listeners resolutely answered "treason" "even in those aspects where I myself was not entirely sure."[30]

February Revolution

During the February Revolution Milyukov hoped to retain the constitutional monarchy in Russia. He became a member of the Provisional Committee of the State Duma on February 27, 1917. Milyukov wanted the monarchy retained, albeit with Alexei as Tsar and the Grand Duke Michael acting as Regent. When Michael awoke on March 2 (O.S.), he discovered that his brother had abdicated in his favor, but Nicholas had not informed him previously and a delegation from the Duma would come to visit him in a few hours. The meeting with Duma President Rodzianko, Prince Lvov, and other ministers, including Milyukov and Kerensky, lasted all morning. Since the masses would not tolerate a new Tsar and the Duma could not guarantee Michael's safety, Michael decided to decline the throne.[31] On March 6, 1917, David Lloyd George gave a cautious welcome to the suggestion of Milyukov that the toppled Tsar and his family could be given sanctuary in Britain, but Lloyd George would have preferred that they go to a neutral country.

Rodzianko succeeded in publishing an order for the immediate return of the soldiers to their barracks, subordinate to their officers.[32] To them, Rodzianko was totally unacceptable as prime minister and Prince Lvov, even less unpopular, became the leader of the new cabinet. In the first Provisional government Milyukov became Minister of Foreign Affairs, taking over the ministry from deputy minister Anatoly Neratov, who had held the office temporarily.

Milyukov sent the British an official request for revolutionary Leon Trotsky to be released from Amherst Internment Camp in Nova Scotia, after the British had boarded a steamer in Halifax harbor to arrest Trotsky and other "dangerous socialists" who were en route to Russia from New York. Upon receiving Milyukov's request the British freed Trotsky, who then continued his journey to Russia and became a key planner and leader of the Bolshevik Revolution that overthrew the provisional government.[33]

On April 20, 1917, the government sent a note to Britain and France (which became known as the Milyukov note) proclaiming that Russia would fulfill its obligation towards the Allies and wage the war as long as it was necessary. On the same day, thousands of armed workers and soldiers came out to demonstrate on the street of Petrograd. Many of them carried banners with slogans calling for the removal of the "ten bourgeois ministers," for an end to the war and for the appointment of a new revolutionary government.[34] The next day the Milyukov Note was condemned by the ministers. This resolved the immediate crisis.[35] On April 29, the minister of war Alexander Guchkov resigned, and Milyukov's resignation followed on May 2 or 4. Milyukov was offered a post as Secretary of Education, but refused. He stayed on as the Kadet leader and began to flirt with counter-revolutionary ideas.[36]

Kornilov Affair

In the mass discontent following the July Days of 1917, primarily about Ukrainian autonomy, the Russian populace grew highly skeptical of the Provisional Government's abilities to alleviate the economic distress and social resentment among the lower classes. The word "provisional" did not command respect.[37] The crowd tired of war and hunger demanded a "peace without annexations or contributions." Milyukov described the situation in Russia in late July as, "Chaos in the army, chaos in foreign policy, chaos in industry and chaos in the nationalist questions." Lavr Kornilov, appointed commander-in-chief of the Russian army in July 1917, considered the Petrograd Soviet responsible for the breakdown in the military since the revolution, and believed that the Russian Provisional Government lacked the power and confidence to dissolve the Petrograd Soviet. Following several ambiguous correspondences between Kornilov and Alexander Kerensky, Kornilov commanded an assault on the Petrograd Soviet.

Because the Petrograd Soviet was able to quickly gather a powerful army of workers and soldiers in defense of the Revolution, Kornilov's coup was an abysmal failure and he was placed under arrest. The so-called Kornilov Affair resulted in significantly increased distrust among Russians towards the Provisional Government.

Exile

On October 26, 1917, the party's newspapers were shut down by the new Soviet Government. On November 25, 1917 Milyukov was elected in the Russian Constituent Assembly, the first truly free election in Russian history. It met for 13 hours but was then banned by the Bolsheviks. On November 28 the party was banned by the Soviets and went underground. Milyukov moved from Petrograd to the Don Host Oblast. There he became a member of the Don civil council. He advised Mikhail Alekseyev of the Volunteer Army. Milyukov and Peter Struve defended a Great Russia as firmly as the most reactionary monarchist.[38] In May 1918 he went to Kiev, where he negotiated with the German high command to act together against the Bolsheviks. For many members of the Kadet Party, this went too far: Milyukov was forced to resign the presidency of the KDP Central Committee.

Milyukov went to Turkey and from there to Western Europe, to gain support from the allies of the White movement in the Russian Civil War. In April 1921 he immigrated to France, where he remained active in politics and edited the Russian-language newspaper Poslednie novosti (Latest News) (1920–1940). In June 1921 he left the Constitutional Democrats, following a division in the party. Milyukov had called on exiles to abandon hopes in counterrevolution at home, and instead to place their hopes in the peasantry to rise up against the hated Bolshevik regime.[39] The debate between Milyukov and Vasily Maklakov began with Maklakov's criticism of the Constitutional Democratic Party. Could the revolutions of 1917 have been prevented if the Kadets had adopted a less radical stance, particularly in 1905-1906?[40] During a performance of the Berliner Philharmonie on March 28, 1922, his friend Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov, the father of the novelist Vladimir Nabokov, was killed while shielding Milyukov from attackers. In 1934, Milyukov was a witness at the Berne Trial.

Although he remained an opponent of the communist regime, Milyukov supported Stalin's "imperial" foreign policy.[41] On the Winter War he commented as follows: "I feel pity for the Finns, but I am for the Vyborg guberniya."[42] Already in 1933 he had stated in Prague that, in case of a war between Germany and the U.S.S.R., "the emigration must be unconditionally on the side of the Homeland." He supported the Soviet Union in its war effort against Nazi Germany and refused all Nazi rapprochements. He rejoiced at the Soviet victory in Stalingrad.

Milyukov died in 1943, in Aix-les-Bains, France. Sometime between 1945 and 1954 his body was reburied at Batignolles Cemetery, in the carré russe-orthodoxe (Russian Orthodox section), division 25, next to his wife, Anna Sergeievna.

Legacy

Milyukov and his contemporaries were confronted with monumental challenges, a disintegrating autocracy, revolutionary upheaval and world war. During the period between the Russian Revolution of 1905 and the February Revolution of 1917, he changed his view on the monarchy. His party, the Kadets were constitutional monarchists, but the monarchy disintegrated under its own weight of failure.[43]

Milyukov tried to hold the middle ground between the government and his liberal colleagues (as well as the more radical socialists), but the middle course only made him a target of both. Orlando Figes called Milyikov's Vyborg Manifesto "a typical example of the Kadets' militant posturing,"[44] while Richard Abraham, in his biography of Kerensky, argues that the withdrawal of the Progressists Party from the coalition with the Kadets in the Fourth Duma was essentially a vote of no confidence in Milyukov and that he grasped at the idea of accusing Stürmer in an effort to preserve his own influence.[45]

During the world war, Milyukov staunchly opposed popular demands for peace at any cost and firmly clung to Russia's wartime alliances. As the Britannica 2004 put it, "he was too inflexible to succeed in practical politics."

Works

- Russia and its crisis (Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press, 1905).

- Constitutional government for Russia an address delivered before the Civic Forum. (New York, NY: Civic Forum, January 14, 1908.

- "Past and present of Russian economics" in Russian realities & problems: Lectures delivered at Cambridge in August 1916, by Pavel Milyukov, Peter Struve, Harold Williams, Alexander Lappo-Danilevsky and Roman Dmowski (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge, University press, 1917).

- Bolshevism: an international danger: its doctrine and its practice through war and revolution (New York, NY: Charles Scriber's Sons, 1920).

- History of the Second Russian Revolution (1921)[46]

- Russia, to-day and to-morrow (New York, NY: The Macmillan Company, 1922).

Notes

- ↑ The Constituent Assembly was declared dissolved by the Bolshevik-Left SR Soviet government, rendering the end the term served.

- ↑ Foreign Minister of the Russian Provisional Government.

- ↑ "RUSSIA STRONGER WITH FREEDOM," New York Times, April 20, 1917. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ↑ "Милюков Павел Николаевич" www.rulex.ru. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ↑ Pavel N. Milyukov, Russia and its Crisis (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1905, ISBN 9780760768631), 150.

- ↑ Orlando Figes, A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891–1924 (New York, NY: Viking Adult, 1997, ISBN 978-0670859160), 204.

- ↑ Figes, 195.

- ↑ The zemstva were organs of local government that had been organized in conjunction with the emancipation of the serfs in 1861.

- ↑ 1905: The Liberation Union (Soyuz Osvobozhdeniya) merged with the Union of Zemstvo-Constitutionalists (Soyuz Zemstev-Konstitutsionistov) to form the liberal Constitutional Democratic Party (Konstitutsiono-Demokraticheskaya Partya), formally known as the Party of Popular Freedom (Partiya Narodnoy Svobody), led by Pavel Milyukov.

- ↑ A. W. Kröner, The Debate Between Miliukov and Maklakov on the Chances for Russian Liberalism (Amsterdam, NL: Ph.D. Thesis, 1998), 173.

- ↑ Charles Louis Seeger, Recollections Of A Foreign Minister (New York, NY: Doubleday Page & Company, 1921). Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- ↑ Figes, 181.

- ↑ Harold Whitmore Williams, Russia of the Russians (1915; Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing, 2008, ISBN 978-1437275971), 112.

- ↑ "Constitutional government for Russia; an address delivered before the Civic forum ...," New York City, January 14, 1908. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ↑ Melissa Kirschke Stockdale, Paul Miliukov and the quest for a liberal Russia, 1880–1918 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996, ISBN 0801432480), 189.

- ↑ Serhii Plokhy, Unmaking Imperial Russia: Mykhailo Hrushevsky and the Writing of Ukrainian History (Toronto, CN: University of Toronto Press, 2005, ISBN 0802039375), 462-463, n. 64.

- ↑ Otto Antrick, Rasputin und die politischen Hintergründe seiner Ermordung (Braunschweig, DE: E. Hunold, 1938), 37.

- ↑ Williams, 79.

- ↑ Maurice Paléologue, An Ambassador's Memoirs Vol. III, Chapter II, (gwpda.org, 1925). Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- ↑ Vratislav Preclík Masaryk a legie (Masaryk and legions), váz. kniha, 219 pages, first issue vydalo nakladatelství Paris Karviná, Žižkova 2379 (734 01 Karvina, Czech Republic) ve spolupráci s Masarykovým demokratickým hnutím (Masaryk Democratic Movement, Prague), 2019, ISBN 978-8087173473), 36–42, 111-112, 124–125, 128-129, 132, 140–148, 184–199.

- ↑ Figes, 287.

- ↑ Stockdale, 234.

- ↑ Pierre Gilliard, Thirteen Years at the Russian Court: the Last Years of the Romanov Tsar and His Family by an Eyewitness (LEONAUR, 2016, ISBN 978-1782825241).

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Robert Paul Browder and Aleksandr Fyodorovich Kerensky, The Russian Provisional Government, 1917: Documents (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1961, ISBN 978-0804700238). Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- ↑ P. N. Milyukov, "Артемий Ермаков. Глупость или измена?" Православие.Ru. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- ↑ Frank A. Golder, Documents of Russian History 1914–1917 (Read Books, 1927, ISBN 1443730297). Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- ↑ Thompson-George-Der-Zar-Rasputin-und-die-Juden. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ↑ Bernard Pares, The Fall of the Russian Monarchy. A Study of the Evidence (London, UK: Jonathan Cape. 1939), 392.

- ↑ Pares, 398.

- ↑ Stockdale, 234.

- ↑ Figes, 344-345.

- ↑ Leon Trotsky, History of the Russian Revolution (Haymarket Books, 2008, ISBN 978-1931859455). Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ↑ "Trotsky's tactical ruthlessness may have won the Bolsheviks Russia. But he almost missed the uprising in a Canadian jail," National Post, July 12, 2014.

- ↑ Figes, 381.

- ↑ Figes, 383.

- ↑ Figes, 443.

- ↑ Figes, 360.

- ↑ Figes, 571.

- ↑ Dinah Jansen, After October: Russian Liberalism as a "Work in Progress, 1919–1945" (Kingston, CN, Queen's University dissertation, 2015).

- ↑ Kröner, 2, 57, 95-100.

- ↑ Boris Borisovich Vail, Милюков и Сахаров in: Мыслящие миры российского либерализма: Павел Милюков (1859–1943). International Conference. Moscow, 23—25 September 2009, 12.

- ↑ Н. Вакар. Милюков в изгнанье // Новый журнал. 1943. Вып. 6. С. 377.

- ↑ Jacob Walkin, The Rise of Democracy in pre-revolutionary Russia (Goleta, CA, Praeger Publishers, 1962), 290.

- ↑ Figes, 221.

- ↑ Richard Abraham, Alexander Kerensky: The First Love of the Revolution (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1987, ISBN 978-0231902182), 113.

- ↑ Страница:Милюков П.Н. - История второй русской революции - 1921: Предисловiе Retrieved November 28, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Abraham, Richard. Alexander Kerensky: The First Love of the Revolution. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0231902182

- Antrick, Otto. Rasputin und die politischen Hintergründe seiner Ermordung. Braunschweig, DE: E. Hunold, 1938.

- Browder, Robert Paul, and Aleksandr Fyodorovich Kerensky. The Russian Provisional Government, 1917: Documents. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1961. ISBN 978-0804700238. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- Figes, Orlando. A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891–1924. New York, NY: Viking Adult, 1997. ISBN 978-0670859160

- Gilliard, Pierre. Thirteen Years at the Russian Court: the Last Years of the Romanov Tsar and His Family by an Eyewitness. LEONAUR, 2016. ISBN 978-1782825241

- Golder, Frank A. Documents of Russian History 1914–1917. Read Books, 1927. ISBN 1443730297. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- Jansen, Dinah. After October: Russian Liberalism as a "Work in Progress," 1919–1945. Kingston, CN, Queen's University dissertation, 2015.

- Kröner, A. W. The Debate Between Miliukov and Maklakov on the Chances for Russian Liberalism. Amsterdam, NL: Ph.D. Thesis, 1998.

- Milyukov, P. N. Russia and its crisis. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press, 1905.

- Pares, Bernard. The Fall of the Russian Monarchy. A Study of the Evidence. London, UK: Jonathan Cape. 1939.

- Paléologue, Maurice. An Ambassador's Memoirs Vol. III, Chapter II,. gwpda.org, 1925. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- Plokhy, Serhii. Unmaking Imperial Russia: Mykhailo Hrushevsky and the Writing of Ukrainian History. Toronto, CN: University of Toronto Press, 2005. ISBN 0802039375

- Seeger, Charles Louis. Recollections Of A Foreign Minister. New York, NY: Doubleday Page & Company, 1921. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- Stockdale, Melissa Kirschke. Paul Miliukov and the Quest for a Liberal Russia, 1880–1918. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1996. ISBN 0801432480

- Trotsky, Leon. History of the Russian Revolution. Haymarket Books, 2008. ISBN 978-1931859455. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- Walkin, Jacob. The Rise of Democracy in pre-revolutionary Russia. Goleta, CA, Praeger Publishers, 1962.

- Williams, Harold Whitmore. Russia of the Russians. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing, 2008 (original 1915). ISBN 978-1437275971

Further reading

- Aldanov, M. "Professor Milyukov on the Russian Revolution." Slavonic Review 6(16) (1927): 223–227.

- Breuillard, Sabine. "Russian Liberalism—Utopia or Realism? The Individual and the Citizen in the Political Thought of Milyukov." in Robert B Mcklean, ed. New Perspectives in Modern Russian History. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 1992. ISBN 978-1349222124, 99–116.

- Elkin, B. I. "Paul Milyukov (1859–1943)" Slavonic and East European Review 23(2) (1945): 137–141.

- Pearson, Raymond. "Milyukov and the Sixth Kadet Congress." Slavonic and East European Review 53(131) (1975): 210–229.

- Riha, Thomas. A Russian European: Paul Miliukov in Russian Politics. South Bend, IN: U of Notre Dame Press, 1969. ISBN 1121788599

- Thatcher, Ian D. "Post-Soviet Russian Historians and the Russian Provisional Government of 1917" Slavonic & East European Review 93(2) (2015): 315–337.

- Zeman, Zbyněk A. A diplomatic history of the First World War.. London, UK: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1971.

Other languages

- Thomas M. Bohn: Russische Geschichtswissenschaft von 1880 bis 1905. Pavel N. Miljukov und die Moskauer Schule. Böhlau, Köln u. a. 1998. ISBN 341212897X

- Бон, Т.М. Русская историческая наука /1880 г. – 1905 г./. Павел Николаевич Милюков и Московская школа. С.-Петербург 2005. ISBN 5901603052.

- Макушин А. В. Трибунский П. А. Павел Николаевич Милюков: труды и дни (1859–1904). — Рязань, 2001. — 439 с. — (Новейшая российская история. Исследования и документы. Том 1.). — ISBN 5944730013

External links

Link retrieved November 24, 2022.

- "An Open Letter to Professor P.N. Miliukov", an early critique of Miliukov's liberalism by Leon Trotsky

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: Nikolai Pokrovsky |

Foreign Minister of Russia 2 March – 1 May 1917 |

Succeeded by: Mikhail Tereshchenko |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.