Red Jacket

Red Jacket (known as Otetiani in his youth and Sagoyewatha after 1780) (c. 1750–January 20, 1830) was a Native American of the Seneca tribe's Wolf Clan. His English name came from the redcoat he wore as an ally of the British in the American Revolution. Red Jacket was known for his excellent memory, gift of oratory, and skill in dealing with the British and the Americans.

In 1786 Red Jacket urged the continuance of hostilities against the whites, but in later years attempted to make peace with the U.S. government. During the War of 1812 he supported the American cause, convincing his people to do so as well.

(IF USE - EDIT = A passionate advocate of the Indian way of life, he resisted the introduction of white customs, especially Christianity and the work of the missionaries. Late in his life the growth of Christianity among Native Americans and opposition to his policies resulted in his being deposed as chief, but he appealed to the government, defended himself before a tribal council, and was restored.)

He died on January 20, 1830, at the Seneca tribal village near Buffalo.

Red Jacket was also known for his oratory skill. His alternative name, Segoyewatha, roughly translates he keeps them awake. He is best known for his response to a New England missionary (a Mr. Cram) who had requested in 1805 to do mission work among the Senecas. Red Jacket's famous speech, as an apologist for the Native American religion, was called Red Jacket on Religion for the White Man and the Red.

Early years

The early years of Otetiani are a matter of tradition; some hold his birth to have been near the foot of Seneca Lake, while others award his birthplace as having been at, or near Canoga, on the banks of the Cayuga Lake. His birth year was around 1750.

He was born into the Wolf Clan of the Seneca tribe, a high ranking family. Members of the clan included Kiasutha, Handsome Lake, Cornplanter, and Governor Blacksnake, all who played principal roles in the relationship between the Seneca and the emerging U.S. nation. He lived most of his life in Seneca territory in the Genesee River Valley. Little else is known of his early years.

The Seneca

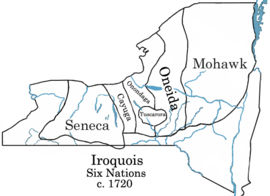

The Seneca were a part of the League of the Iroquois, which also included the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, and the Cayuga tribes. The League eventually welcomed the Tuscarora, and became commonly known as the "Six Nations."

The Iroquois were known as a formidable force, made so by the union of the tribes. By their united strength they were able to repel invasion, from any of the surrounding nations, and by the force of their arms and their prowess in war, gained control over an extent of territory much greater than that which they occupied.

The Seneca, the westernmost tribe, were the largest and most powerful of the League's tribes. They were divided into two areas, the Seneca Lake region and the Allegheny River region. Red Jacket was of the northern Seneca Lake group.

American Revolutionary War

Initially, both British and American officials discouraged the Iroquois from getting involved in the War of Independence, stating that the issues between the two were of no consequence to the Indians.[1] Eventually, though, the British openly appealed to the Iroquois to declare war against the Americans. In July 1777 an Iroquois League council with the British was held in Oswego. When urged to join the war on the British side, the League protested that they had committed to neutrality and could not without violating their promise, take up the hatchet. In response, they were assured that the "rebels" justly merited punishment. Having had a relationship of over 100 years with the British, a majority decision - with the exception of a large faction of Oneidas - was made to take up arms against the Americans.

Red Jacket did not approve. He declared plainly and unhesitatingly to those who had determined to engage in the war; "This quarrel does not belong to us, and it is test for us to take no part in it; we need not waste our blood to have it settled. If they fight us, we will fight them, but if they let us alone, we had better keep still."[2]

At the time Red Jacket was but 26 years old, and not yet a chief. His opinions held little weight, but he did not hesitate to give them. When the Seneca were requested to join the forces that were preparing to march under the command of Col. St. Leger upon Fort Stanwix, he cautioned against it. He was labeled a coward, and the warriors prepared for battle. The Senecas fell under the command of Thayendanegea (Joseph Brant), who went with a company of Tories led by Colonel Butler. The Seneca suffered heavy loss of life in that engagement.

Though often taunted as a coward, Red Jacket maintained his stance of negotiation over battle throughout the war. Yet it was in this war that Red Jacket received his English name. Distinguished for his fleetness on foot, his intelligence and energy, he attracted the attention of a British officer. Impressed with the young man's manners, energy, and the speedy execution of those errands with which he was entrusted, he received a gift of a beautifully embroidered red jacket. He proudly wore his jacket, and when it wore out, another was gifted to him. It became his trademark, and the British saw to it that he received a new one as needed.

Post-Revolutionary War years

1784 Treaty of Fort Stanwix

By the end of the War of Independence, Red Jacket had been named a Sachem of the Seneca. As a tribal leader, he took part in the October 1784 Treaty of Fort Stanwix (in present-day Rome, New York). The treaty was meant to serve as a peace treaty between the Iroquois and the Americans, in part to make up for the slighting of the Native Americans in the Treaty of Paris. Joseph Brant, the leading tribal chief at the beginning of negotiations, stated, "But we must observe to you, that we are sent in order to make peace, and that we are not authorized, to stipulate any particular cession of lands."[3] Brant had to leave early for a planned trip to England, and the council continued in his absence.

Cornplanter assumed the position of leading Indian representative in Brant's stead. The treaty was signed by he and Captain Aaron Hill. In this treaty the Iroquois Confederacy ceded all claims to the Ohio territory, a strip of land along the Niagara River, and all land west of mouth of Buffalo creek. Red Jacket strenuously resisted the treaty, regarding the proposed cession of lands as exorbitant and unjust, and summoned all the resources of his eloquence to defend his position. Resulting from his delivery of an impassioned plea for the Iroquois to refuse such conditions placed upon them, he became known as the peerless orator of his Nation.

Subsequently, the Six Nations council at Buffalo Creek refused to ratify the treaty, denying that their delegates had the power to give away such large tracts of land. The general Western Confederacy also disavowed the treaty because most of the Six Nations did not live in the Ohio territory. The Ohio Country natives, including the Shawnee, Mingo, Delaware, and several other tribes rejected the treaty.

Treaty of Canandaigua

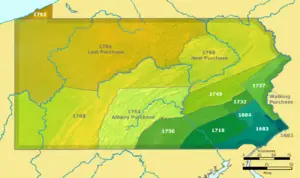

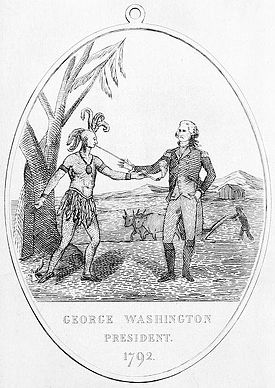

The Treaty of Canandaigua was signed at Canandaigua, New York on November 11, 1794. Red Jacket was a signatory along with Cornplanter and fifty other sachems and war chiefs representing the Grand Council of the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, and by Timothy Pickering, official agent of President George Washington. The treaty "affirmed peace and friendship" between the United States and the Six Nations, and affirmed Haudenosaunee land rights in the state of New York, and the boundaries established by the Phelps and Gorham Purchase of 1788.

Though Red Jacket regretted the loss of any more territory, he concluded it was better to lose a part, than to be deprived of all. And by throwing his influence decidedly in favor, he succeeded finally in quieting the minds of his people, and in persuading them to accede to the proposals made.

Red Jacket replaces Cornplanter

In 1797, Robert Morris - a British born American merchant known as the Financier of the Revolution because of his role in personally financing the American side in the Revolutionary War from 1781 to 1784 - purchased rights to some lands west of the Genesee River from the Senecas for $100,000 through the Treaty of Big Tree. Red Jacket attempted to prevent the sale, but unable to convince others, gave up his opposition. The sale was well "greased" by a great deal of liquor and bribes of trinkets to the Iroquois women. Morris, who had previously purchased the land from Massachusetts, subject to the Indian title, then sold it to the Holland Land Company, retaining only the Morris Reserve, an estate near present day Rochester New York. Soon after, the Seneca came to realize the weight of their decision. The broad lands - mountains, hills, and valleys - over which they had previously roamed freely were no longer theirs. While they remained within their sight, they could not be visited.

Cornplanter, the tribal leader who had supported the greatest sales of lands and signed them away on the tribe's behalf, fell out of favor. Red Jacket, who had almost always opposed the same treaties which Cornplanter promoted, began to garner the favored position among his people.

The long rivalry between Cornplanter and Red Jacket came to a head when the former, prompted by the religious leader Handsome Lake, accused Red Jacket of witchcraft. Such an accusation among the Seneca required a trial. Red Jacket conducted the trial in his own defense, and while the people were divided, he ultimately prevailed. Had he been unsuccessful in defending himself he might have faced the ultimate condemnation, death. The victory which Red Jacket thus achieved recoiled heavily on Cornplanter, and gave him a blow from which he never afterward fully recovered. He retired to land along the western bank of the Allegheny River which had been gifted to him by the Pennsylvania General Assembly in gratitude for his efforts of reconciliation.

Later years

In the early 1800s Red Jacket became a strong traditionalist and sought to return the Seneca to the old ways of life. He opposed the efforts of Americans to assimilate the Native peoples into the white culture through methods of education which were unnatural and even harmful to their way of life. He voiced strong opposition to Christian conversion. At the same time, he was caught in the middle between the new Seneca zealot, Handsome Lake, and both white and Indian Christians on the other side.

While he resisted the Americanization of the Native peoples, he nonetheless followed a policy of friendship toward the United States government. When the Shawnee prophet Tecumseh advocated inter-tribal alliance as a means to end the encroachment of the white settlers upon Native American lands, Red Jacket opposed his efforts.

He urged neutrality in the War of 1812 between Great Britain and the U.S. When the Seneca eventually joined the war on the American side, Red Jacket joined as well, engaging in several battles.

By the 1820s, many of the Seneca had converted to Christianity. Red Jacket's strong opposition to this religion, compounded by a problem with alcohol, prompted an effort to remove him from leadership. In September 1827 a council of 25 elders dissolved his chieftainship. He then traveled to Washington and sought the counsel of both the Secretary of War and the head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Following their advice, upon returning home he adopted a more peaceable attitude toward those of differing views. Soon a second meeting of the tribal council restored his leadership position.

It was in this decade also, that Red Jacket's wife became Christian. He left her in anger and despair, visiting from village to village for several months, before returning. Following his return, many noticed that he had mellowed with respect to the stand he had taken against Christianity. His wife's example, who was a woman of humble, consistent piety, exerted a salutary, and happy influence upon him. It led him to regard Christianity more favorably, and to reconsider the hostile position he had previously maintained. He talked of peace, and sought to bring about a reconciliation between the two parties. He convened a council with this intent, and made special preparations to attend. However, he took ill and did not attend. He stayed in his home with his wife and daughter, and after several days he died, surrounded by his family. The date was January 20, 1830.

Red Jacket had requested not to be mourned in the Native manner, as a funeral for a distinguished person was a pompous affair, continuing for ten days. Every night a fire was kindled at the grave, around which the mourners gather and wail. Instead, he requested a humble funeral in the manner of his wife's new religion. His requested, though, to be buried among his own people, so that if the dead rise as the minister taught he would be among his own people. "I wish to rise with my old comrades. I do not wish to rise among pale faces. I wish to be surrounded by red men."[2]

His funeral, a simple affair, was largely attended by his own race, and by the whites living in that vicinity. He was buried in the mission burying ground, among many of his race. In 1884, his remains, along with those of other Seneca tribal leaders, were reinterred in Forest Lawn Cemetery in Buffalo, where a memorial now stands.

Legacy

- A complex of dormitory buildings at the University at Buffalo is named after him.

- Red Jacket Dining Hall at SUNY Geneseo is named after him.

- The Red Jacket clipper ship that set the unbroken speed record from New York to Liverpool is named after him.[4]

- A public school system, Red Jacket Central, also is named in honor of Segoyewatha and serves the communities of Manchester and Shortsville in Ontario County, New York.

- A section of the Buffalo River in New York is named "Red Jacket Peninsula" in his honor. An informational plaque anointing the aforementioned, with a brief Red Jacket bio as well as other river history, is located along the eastern bank of the river (close to the mouth) at a New York State Department of Environmental Conservation access park, located at the southwestern end of Smith Street in Buffalo, New York.

- The community of Red Jacket in southern West Virginia was named for him, though he is not known to have had any personal connection to that region.[5]

- Red Jacket also has a memorial statue in Red Jacket Park in Penn Yan, New York. The statue was sculpted by Michael Soles.

Notes

- ↑ Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Chief Cornplanter Retrieved January 29, 2009.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 John Niles Hubbard. An account of Sa-Go-Ye-Wat-Ha: Red Jacket and his people, 1750-1830 Project Gutenberg. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ↑ Isabel Kelsay. 1984. Joseph Brant 1743-1807 Man of Two Worlds. (ISBN 0815601824) p 359.

- ↑ Isaacson. pp 260–261.

- ↑ Kenny. p 524.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Graymont, Barbara. 1972. The Iroquois in the American Revolution. A New York State study. [Syracuse, N.Y.]: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0815600836

- Kenny, Hamill. 1945. West Virginia place names, their origin and meaning, including the nomenclature of the streams and mountains. Piedmont, W. Va: Place name Press. OCLC 404442

- Koch, Robert G. 1992. Red Jacket: Seneca Orator Crooked Lake Review. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- Red Jacket. 1805. Red Jacket on Religion for the White Man and Red Bartleby Books Online. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- Isaacson, Dorris A., and Maine League of Historical Societies and Museums. 1970. Maine, a guide "down east.". American guide series. Rockland, Me: Courier-Gazette. OCLC 143588

- Wallace, Anthony F. C. 1972. The death and rebirth of the Seneca. Vintage books, 699. New York, NY: Random House. ISBN 039471699X

External links

All Links Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- An Account of Sa-Go-Ye-Wat-Ha, or Red Jacket, and His People, available for free via Project Gutenberg by John Niles Hubbard

- Red Jacket at Find A Grave

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.