Ramadan

Working on - Jennifer Tanabe April 2020

| Ramadan رَمَضَان | |

|---|---|

| |

| A crescent moon can be seen over palm trees at Manama, marking the beginning of the Islamic month of Ramadan in Bahrain. | |

| Also called | *Azerbaijani: Ramazan

|

| Observed by | Muslims |

| Type | Religious |

| Begins | At the last night of the month of Sha'ban[1] |

| Ends | At the last night of the month of Ramadan[1] |

| Date | Variable (follows the Islamic lunar calendar)[2] |

| Celebrations | Community iftars and Community prayers |

| Observances |

|

| Related to | Eid al-Fitr, Laylat al-Qadr |

Ramadan (also spelled Ramzan, Ramadhan, or Ramathan) is the ninth month of the Islamic calendar, observed by Muslims worldwide as a month of fasting (sawm), prayer, reflection and community. A commemoration of Muhammad's first revelation, the annual observance of Ramadan is regarded as one of the Five Pillars of Islam and lasts twenty-nine to thirty days, from one sighting of the crescent moon to the next.

Fasting from sunrise to sunset is fard (obligatory) for all adult Muslims in good health. Before the daily fast each day a predawn meal, referred to as suhur is eaten, and the fast is broken with a nightly feast called iftar.

The spiritual rewards (thawab) of fasting are believed to be multiplied during Ramadan. Accordingly, Muslims refrain not only from food and drink, but also tobacco products, sexual relations, and sinful behavior, devoting themselves instead to salat (prayer) and recitation of the Quran.

Etymology

The word Ramadan originally "the hot month," derives from the Arabic root R-M-Ḍ (ramida) (ر-م-ض) "be burnt, scorched." [3] According to numerous hadiths, Ramadan is one of the names of God in Islam (the 99 Names of Allah, Beautiful Names of Allah) and as such it is prohibited to say only "Ramadan" in reference to the calendar month, and that it is necessary to say the "month of Ramadan."

History

Ramadan is observed by Muslims worldwide as a commemoration of Muhammad's first revelation. The annual observance of sawm (fasting during Ramadan) is regarded as one of the Five Pillars of Islam and lasts twenty-nine to thirty days, from one sighting of the crescent moon to the next.[4][5]

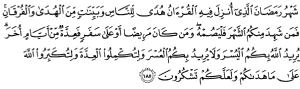

The month of Ramadan is that in which was revealed the Quran; a guidance for mankind, and clear proofs of the guidance, and the criterion (of right and wrong). And whosoever of you is present, let him fast the month, and whosoever of you is sick or on a journey, a number of other days. Allah desires for you ease; He desires not hardship for you; and that you should complete the period, and that you should magnify Allah for having guided you, and that perhaps you may be thankful.[Quran 2:185]

Muslims hold that all scripture was revealed during Ramadan, the scrolls of Abraham, Torah, Psalms, Gospel, and Quran having been handed down on the first, sixth, twelfth, thirteenth (in some sources, eighteenth) and twenty-fourth Ramadans, respectively.[6] Muhammad is said to have received his first quranic revelation on Laylat al-Qadr, one of five odd-numbered nights that fall during the last ten days of Ramadan.[7]

Important dates

The first and last dates of Ramadan are determined by the lunar Islamic calendar.[2]

Beginning

Because Hilāl, the crescent moon, typically occurs approximately one day after the new moon, the beginning of Ramadan can be estimated with some accuracy (see chart). The opening of Ramadan can be confirmed by direct visual observation of the crescent.[4]

Night of Power

Laylat al-Qadr (Night of Power) is considered the holiest night of the year.[8] It is, in Islamic belief, the night when the first verses of the Quran were revealed to the prophet Muhammad. According to many Muslim sources, this was one of the odd-numbered nights of the last ten days of Ramadan, traditionally believed to be the twenty-third night of Ramadan.[9] Since that time, Muslims have regarded the last ten nights of Ramadan as being especially blessed. The Night of Qadr comes with blessings and mercy of God in abundance, sins are forgiven, supplications are accepted, and that the annual decree is revealed to the angels, who carry it out according to God's plan.

Eid

The holiday of Eid al-Fitr (Arabic:عيد الفطر), which marks the end of Ramadan and the beginning of Shawwal, the next lunar month, is declared after a crescent new moon has been sighted or after completion of thirty days of fasting if no sighting of the moon is possible. Also called the "Festival of Breaking the Fast," Eid al-Fitr celebrates of the return to a more natural disposition (fitra) of eating, drinking, and marital intimacy. It is forbidden to fast on the Day of Eid, and a specific prayer is nominated for this day.[10] As an obligatory act of charity, money is given to the poor and the needy before performing the Eid prayer. After the prayers, Muslims may visit their relatives, friends, and acquaintances or hold large communal celebrations in homes, community centers, or rented halls.

Religious practices

During the month of Ramadan the common practice is to fast from dawn to sunset.

Muslims also devote more time to prayer and acts of charity, striving to improve their self-discipline.

Fasting

Ramadan is a time of spiritual reflection, self-improvement, and heightened devotion and worship. Muslims are expected to put more effort into following the teachings of Islam. The fast (sawm) begins at dawn and ends at sunset. The act of fasting is said to redirect the heart away from worldly activities, its purpose being to cleanse the soul by freeing it from harmful impurities. Ramadan is an opportunity to practice self-discipline, self-control,[11] sacrifice, and empathy for those who are less fortunate, thus encouraging actions of generosity and compulsory charity (zakat).[12]

Exemptions to fasting include travel, menstruation, severe illness, pregnancy, and breastfeeding. Muslims with medical conditions are recommended not to fast, although those unable to fast due to travel of temporary sickness are obligated make up the missed days later.[13]

Suhoor

Each day before dawn, Muslims observe a pre-fast meal called the suhoor ("pre-dawn meal"). Sahur is regarded by Islamic traditions as a benefit of the blessings in that it allows the person fasting to avoid the crankiness or weakness caused by the fast. According to a hadith in Sahih al-Bukhari, Anas ibn Malik narrated, "The Prophet said, 'take sahur as there is a blessing in it.'"[14]

After the meal, and still before dawn, Muslims begin the first prayer of the day, Fajr.[15]

Iftar

At sunset, families break the fast with the iftar, traditionally opening the meal by eating dates to commemorate Muhammad's practice of breaking the fast with three dates.[16] They then adjourn for Maghrib, the fourth of the five required daily prayers, after which the main meal is served.[17]

Social gatherings, with the food many times served in buffet style, are frequent at iftar. Traditional dishes are often highlighted. Water is usually the beverage of choice, but juice and milk are also often available, as are soft drinks and caffeinated beverages.[18]

In the Middle East, iftar consists of water, juices, dates, salads, and appetizers; one or more main dishes; and rich desserts, with dessert considered the most important aspect of the meal.[19] Typical main dishes include lamb stewed with wheat berries, lamb kebabs with grilled vegetables, and roasted chicken served with chickpea-studded rice pilaf. Desserts may include luqaimat, baklava, or kunafeh.[20]

Over time, the practice of iftar has involved into banquets that may accommodate hundreds or even thousands of diners. The Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque in Abu Dhabi, the largest mosque in the UAE, feeds up to thirty thousand people every night.[21] Some twelve thousand people attend iftar every night at the Imam Reza shrine in Mashhad.[22]

Nightly prayers

Tarawih (Arabic: تراويح) are extra nightly prayers performed during the month of Ramadan. Contrary to popular belief, they are not compulsory.[23]

Recitation of the Quran

Muslims are encouraged to read the entire Quran, which comprises thirty juz' (sections), over the thirty days of Ramadan. Some Muslims incorporate a recitation of one juz' into each of the thirty tarawih sessions observed during the month.[24]

Charity

Zakāt, often translated as "the poor-rate", is the fixed percentage of income a believer is required to give to the poor; the practice is obligatory as one of the pillars of Islam. Muslims believe that good deeds are rewarded more handsomely during Ramadan than at any other time of the year; consequently, many[attribution needed] donate a larger portion—or even all—of their yearly zakāt during this month.[citation needed]

Cultural practices

In some Islamic countries, lights are strung up in public squares and across city streets,[25][26][27] a tradition believed to have originated during the Fatimid Caliphate, where the rule of Caliph al-Mu'izz li-Din Allah was acclaimed by people holding lanterns.[28]

On the island of Java, many believers bathe in holy springs to prepare for fasting, a ritual known as Padusan.[29] The city of Semarang marks the beginning of Ramadan with the Dugderan carnival, which involves parading the Warak ngendog, a horse-dragon hybrid creature allegedly inspired by the Buraq.[30] In the Chinese-influenced capital city of Jakarta, firecrackers are widely used to celebrate Ramadan, although they are officially illegal.[31] Towards the end of Ramadan, most employees receive a one-month bonus known as Tunjangan Hari Raya.[32] Certain kinds of food are especially popular during Ramadan, such as large beef or buffalo in Aceh and snails in Central Java.[33] The iftar meal is announced every evening by striking the bedug, a giant drum, in the mosque.[34]

Common greetings during Ramadan include Ramadan mubarak and Ramadan kareem.[35]

During Ramadan in the Middle East, a mesaharati beats a drum across a neighbourhood to wake people up to eat the suhoor meal. Similarly in Southeast Asia, the kentongan slit drum is used for the same purpose.

|

Observance

Fasting from sunrise to sunset is fard (obligatory) for all adult Muslims who are not acutely or chronically ill, travelling, elderly, pregnant, breastfeeding, diabetic, or menstruating.[36] The predawn meal is referred to as suhur, and the nightly feast that breaks the fast is called iftar.[37][38] Although fatwas have been issued declaring that Muslims who live in regions with a midnight sun or polar night should follow the timetable of Mecca,[39] it is common practice to follow the timetable of the closest country in which night can be distinguished from day.[40][41][42]

The spiritual rewards (thawab) of fasting are believed to be multiplied during Ramadan.[43] Accordingly, Muslims refrain not only from food and drink, but also tobacco products, sexual relations, and sinful behavior,[44][45] devoting themselves instead to salat (prayer), recitation of the Quran,[46][47] and the performance of charitable deeds[citation needed] as they strive for purity and heightened awareness of God (taqwa).[citation needed]

According to a 2012 Pew Research Centre study, there was widespread Ramadan observance, with a median of 93 percent across the thirty-nine countries and territories studied.[48] Regions with high percentages of fasting among Muslims include Southeast Asia, South Asia, Middle East and North Africa, Horn of Africa and most of Sub-Saharan Africa.[48] Percentages are lower in Central Asia and Southeast Europe.[48]

Ramadan in polar regions

The length of the dawn to sunset time varies in different parts of the world according to summer or winter solstices of the Sun. Most Muslims fast for eleven to sixteen hours during Ramadan. However, in polar regions, the period between dawn and sunset may exceed twenty-two hours in summer. For example, in 2014, Muslims in Reykjavik, Iceland, and Trondheim, Norway, fasted almost twenty-two hours, while Muslims in Sydney, Australia, fasted for only about eleven hours. In areas characterized by continuous night or day, some Muslims follow the fasting schedule observed in the nearest city that experiences sunrise and sunset, while others follow Mecca time.[40][41][42]

Ramadan in Earth orbit

Muslim astronauts in space schedule religious practices around the time zone of their last location on Earth. For example, this means an astronaut from Malaysia launching from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida would center their fast according to sunrise and sunset in Eastern Standard Time. This includes times for daily prayers, as well as sunset and sunrise for Ramadan.[49][50]

Laws

In some Muslim countries, failing to observe the Ramadan fast is a crime.[51][52][53] The sale of alcohol is prohibited in Egypt.[54] In Kuwait, the penalty for eating, drinking or smoking during daytime is a fine of no more than one hundred Kuwaiti dinar or incarceration for no more than one month, or both.[55][56] In some United Arab Emirates jurisdictions, eating or drinking in public is considered a minor offence punishable by up to one hundred fifty hours of community service.[57] Courts in Saudi Arabia, described by The Economist as taking Ramadan "more seriously than anywhere else",[58] may impose harsher punishments, including flogging, imprisonment and, for non-Muslim foreigners who consume food or drink in public, deportation.[59][60] In Malaysia, breaking the fast prior to sundown may result in arrest by the religious police, while the sale of food, drink, or tobacco for immediate consumption can incur a fine of up to one thousand ringgit and six months' imprisonment, penalties that are doubled for repeat offenses.[61] Courts in Algeria have imposed fines and prison sentences for violations of Ramadan regulations.[62]

Some countries impose modified work schedules. In the UAE, employees may work no more than six hours per day and thirty-six hours per week. Qatar, Oman, Bahrain and Kuwait have similar laws.[63]

Employment during Ramadan

Muslims continue to work during Ramadan;[64][65] however, in some Islamic countries, such as Oman and Lebanon, working hours are shortened.[66][67] It is often recommended that working Muslims inform their employers if they are fasting, given the potential for the observance to impact performance at work.[68] The extent to which Ramadan observers are protected by religious accommodation varies by country. Policies putting them at a disadvantage compared to other employees have been met with discrimination claims in the United Kingdom and the United States.[69][70][71]

Health

Ramadan fasting is safe for healthy people, but those with medical conditions should seek medical advice if they encounter health problems before or during fasting.[72] The fasting period is usually associated with modest weight loss, but weight can return afterwards.[73]

The education departments of Berlin and the United Kingdom have tried to discourage students from fasting during Ramadan, as they claim that not eating or drinking can lead to concentration problems and bad grades.[74][75]

A review of the literature by an Iranian group suggested fasting during Ramadan might produce renal injury in patients with moderate (GFR <60 ml/min) or severe kidney disease but was not injurious to renal transplant patients with good function or most stone-forming patients.[76]

Ramadan fasting can be potentially hazardous for pregnant women as it is associated with risks of inducing labour and causing gestational diabetes, although it does not appear to affect the child's weight. It is permissible to not fast if it threatens the woman's or the child's lives.[77][78][79][80][81]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Malcolm Clark, Islam For Dummies (John Wiley & Sons, 2003, ISBN 978-0764555039).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 When does Ramadan begin in 2020? Al Jazeera, April 22, 2020. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ↑ Ramadan Etymology Online. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 AbdAllah-Muhammad Bukhari-Ibn-Ismail, Sahih Bukhari – Book 031 (The Book of Fasting), Hadith 124 Hadith Collection. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ↑ Abul-Hussain Muslim-Ibn-Habaj, Sahih Muslim – Book 006 (The Book of Fasting), Hadith 2378 Hadith Collection. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ↑ Rafig Y. Aliyev, Loud Thoughts on Religion (Trafford Publishing, 2013, ISBN 978-1490705217).

- ↑ Mahmood Bin Ahmad Ad-Dausaree, The Magnificence of Quran (Darussalam Publishers, 2015, ISBN 978-9960980119).

- ↑ Neal Robinson, Islam: A Concise Introduction (Georgetown University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0878402243).

- ↑ Bombay Tract and Book Society, Life of Mohammed (Wentworth Press, 2019, ISBN 978-0353880443).

- ↑ Deborah Heiligman, Holidays Around the World: Celebrate Ramadan and Eid al-Fitr with Praying, Fasting, and Charity (National Geographic Children's Books, 2006, ISBN 978-0792259268).

- ↑ Adam Yosef, Why Ramadan brings us together BBC, August 25, 2009. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- ↑ Thomas Erdbrink, Help for the Heavy at Ramadan Washington Post, September 28, 2008. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- ↑ Quran 2:184

- ↑ Bukhari: Book 3: Vol. 31: Hadith 146 (Fasting).

- ↑ Abul-Hussain Muslim-Ibn-Habaj, Sahih Muslim – Book 006 (The Book of Fasting), Hadith 2415 Hadith Collection. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ↑ John L. Esposito, The Oxford dictionary of Islam (Oxford University Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0195125597).

- ↑ Melissa Fletcher Stoeltje, Muslims fast and feast as Ramadan begins San Antonio Express-News, August 22, 2009. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ↑ Nour El-Zibdeh, [https://www.todaysdietitian.com/newarchives/072709p56.shtml Understanding Muslim Fasting Practices ' Today's Dietitian, 11(8) (August 2009): 56. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ↑ Darra Goldstein (ed.), The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets (Oxford University Press, 2015, ISBN 978-0199313396).

- ↑ Faye and Yakir Levy, Ramadan's high note is often a dip Los Angeles Times, July 21, 2012. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ↑ Abu Dhabi's Grand Mosque feeds 30,000 during Ramadan Euro News, May 10, 2019. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ↑ Gisoo Misha Ahmadi, Iran's Mashhad hosts biggest "Iftar" in world Press TV, July 11, 2015. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- ↑ Tarawih Prayer a Nafl or Sunnah.

- ↑ Underst, Huda Huda is the author of "The Everything. How Do Muslims Celebrate Ramadan? (in en).

- ↑ Muslims begin fasting for Ramadan. ABC News (18 July 2012).

- ↑ Taryam Al Subaihi (29 July 2012). The spirit of Ramadan is here, but why is it still so dark?. The National.

- ↑ Cochran, Sylvia (8 August 2011). How to decorate for Ramadan. Yahoo-Shine.

- ↑ Harrison, Peter, "How did the Ramadan lantern become a symbol of the holy month?", Al Arabiya, 2016-06-09.

- ↑ "This Is How Indonesia Welcomes Ramadan", Jakarta Globe, 2019-05-04.

- ↑ Tradisi Dugderan di Kota Semarang (in id). Mata Sejarah.

- ↑ Sims, Calvin, "Jakarta Journal; It's Ramadan. School Is Out. Quick, the Earplugs!", The New York Times, 2000-12-19.

- ↑ Understanding the Religious Holiday Allowance THR in Indonesia (2018-12-06).

- ↑ Maryono, Agus, "On the hunt for delectable snacks", The Jakarta Post, 2014-07-07.

- ↑ Saifudeen, Yousuf, "Diverse traditions that welcome the holy month in Indonesia", Khaleej Times, 2016-06-12.

- ↑ Ramadan 2015: Facts, History, Dates, Greeting And Rules About The Muslim Fast {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}}, Huffington Post, 15 June 2015

- ↑ Fasting (Al Siyam) – الصيام – p. 18, el Bahay el Kholi, 1998

- ↑ Islam, Andrew Egan – 2002 – p. 24

- ↑ Dubai – p. 189, Andrea Schulte-Peevers – 2010

- ↑ Ramadan in the Farthest North.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 See article "How Long Muslims Fast For Ramadan Around The World" -Huffingtonpost.co /31 July 2014 and article "Fasting Hours of Ramadan 2014" -Onislam.net / 29 June 2014 and article "The true spirit of Ramadan" -Gulfnews.com /31 July 2014

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 See article by Imam Mohamad Jebara "The fasting of Ramadan is not meant to punish" https://ottawacitizen.com/opinion/columnists/jebara-the-fasting-of-ramadan-is-not-meant-to-punish {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}}

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Kassam, Ashifa (3 July 2016). Arctic Ramadan: fasting in land of midnight sun comes with a challenge. The Guardian.

- ↑ Bukhari-Ibn-Ismail, AbdAllah-Muhammad. Sahih Bukhari – Book 031 (The Book of Fasting), Hadith 125.. hadithcollection.com.

- ↑ (2010) Islam in America. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231147101.

- ↑ (2003) Islam Without Illusions: Its Past, Its Present, and Its Challenge for the Future. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0815607663.

- ↑ Abu Dawud-Ibn-Ash'ath-AsSijisstani, Sulayman. Sunan Abu-Dawud – (The Book of Prayer) – Detailed Injunctions about Ramadan, Hadith 1370. Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement of The University of Southern California.

- ↑ Bukhari-Ibn-Ismail, AbdAllah-Muhammad. Sahih Bukhari – Book 031 (The Book of Fasting), Hadith 199.. hadithcollection.com.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 Most Muslims say they fast during Ramadan (9 July 2013).

- ↑ A Guideline of Performing Ibadah at the International Space Station (ISS)

- ↑ Donadio, Rachel, "Interstellar Ramadan", The New York Times, 2007-12-09. (written in en-US)

- ↑ Ramadan 2019: 9 questions about the Muslim holy month you were too embarrassed to ask. Vox (6 June 2016).

- ↑ Breaking Pakistan's Ramadan Fasting Laws Has Serious Consequences. NPR.

- ↑ Not so fast! Ramadan laws in Arab countries make you think twice before digging in. Albawaba News.

- ↑ "Egypt's tourism minister 'confirms' alcohol prohibition on Islamic holidays beyond Ramadan {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}}," Al-Ahram, 22 July 2012.

- ↑ Press release by Kuwait Ministry Of Interior.

- ↑ "KD 100 fine, one month prison for public eating, drinking", Kuwait Times Newspaper, 21 August 2009.

- ↑ Salama, Samir, "New penalty for minor offences in UAE", Al Nisr Publishing LLC, 16 July 2009.

- ↑ "Ramadan in Saudi Arabia: Taking it to heart", The Economist, 11 June 2016.

- ↑ "Ramadan warning for expats in Saudi Arabia", 24 July 2012.

- ↑ Ramadan in numbers {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}}, 10 July 2013, The Guardian

- ↑ The Hard and Fast Rules of Ramadan (14 July 2015).

- ↑ Algerians jailed for breaking Ramadan fast. Al Arabiya News (7 October 2008).

- ↑ Employment Issues During Ramadan – The Gulf Region, DLA Piper Middle East.

- ↑ Ramadan 2019: Why is it so important for Muslims?.

- ↑ Gilfillan_1, Scott (2019-05-03). Supporting Muslim colleagues during Ramadan (in en).

- ↑ Ramadan working hours announced in Oman. Times of Oman (22 June 2014).

- ↑ Ramadan working hours announced for public and private sectors. Times of Oman (10 June 2015).

- ↑ The Working Muslim in Ramadan. Working Muslim (2011).

- ↑ Lewis Silkin (26 April 2016). Lewis Silkin – Ramadan – employment issues. lewissilkinemployment.com.

- ↑ Reasonable Accommodations for Ramadan? Lessons From 2 EEOC Cases. Free Enterprise.

- ↑ EEOC And Electrolux Reach Settlement in Religious Accommodation Charge Brought By Muslim Employees. eeoc.gov.

- ↑ (2010). Islamic fasting and health. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 56 (4): 273–282.

- ↑ (2014). Islamic fasting and weight loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Nutr 17 (2): 396–406.

- ↑ "Schools say Muslim students 'should break Ramadan fast' to avoid bad grades", The Telegraph. (written in en-GB)

- ↑ Prof. Dr. E. Jürgen Zöllner (Summer 2017). Education in Berlin: Islam and School. Senatsverwaltung für Bildung, Wissenschaft und Forschung.

- ↑ (August 2013) Ramadan fasting and patients with renal diseases: A mini review of the literature. J Res Med Sci 18 (8): 711–716.

- ↑ (25 October 2018) The effect of Ramadan fasting during pregnancy on perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis.. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 18 (1): 421.

- ↑ Islamic Studies Maldives

- ↑ (2019) "Chapter 22: Obesity, Polycystic Ovaries and Impaired Reproductive Outcome", Obesity. Elsevier, 289–298. DOI:10.1016/B978-0-12-416045-3.00022-4. ISBN 978-0-12-416045-3.

- ↑ (January 2006) The effect of maternal diet restriction on pregnancy outcome.. American Journal of Perinatology 23 (1): 21–24.

- ↑ (1 April 2014) Implications of Ramadan intermittent fasting on maternal and fetal health and nutritional status: A review. Mediterranean Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism 7 (2): 107–118.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ad-Dausaree, Mahmood Bin Ahmad. The Magnificence of Quran. Darussalam Publishers, 2015. ISBN 978-9960980119

- Aliyev, Rafig Y. Loud Thoughts on Religion: A Version of the System Study of Religion. Useful Lessons for Everybody. Trafford Publishing, 2013. ISBN 978-1490705217

- Bombay Tract and Book Society. Life of Mohammed. Wentworth Press, 2019. ISBN 978-0353880443)

- Clark, Malcolm. Islam For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons, 2003. ISBN 978-0764555039

- Esposito, John L. The Oxford dictionary of Islam. Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0195125597

- Heiligman, Deborah. Holidays Around the World: Celebrate Ramadan and Eid al-Fitr with Praying, Fasting, and Charity. National Geographic Children's Books, 2006. ISBN 978-0792259268

- Robinson, Neal. Islam: A Concise Introduction. Georgetown University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0878402243

External links

All links retrieved

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.