Prose

Prose is a form of written or spoken language that follows the natural flow of speech, uses a language's ordinary grammatical structures, or follows the conventions of formal academic writing. It differs from most traditional poetry, where the form consists of verse (writing in lines) based on rhythmic meter or rhyme. The word "prose" first appears in English in the 14th century. It is derived from the Old French prose, which in turn originates in the Latin expression prosa oratio (literally, straightforward or direct speech).[1] Works of philosophy, history, economics, etc., journalism, and most fiction (an exception is the verse novel), are examples of works written in prose. Developments in twentieth century literature, including free verse, concrete poetry, and prose poetry, have led to the idea of poetry and prose as two ends on a spectrum rather than firmly distinct from each other. The British poet T. S. Eliot noted, whereas "the distinction between verse and prose is clear, the distinction between poetry and prose is obscure."[2]

History

| History of literature by region or country | |||||||

| General topics | |||||||

| |||||||

| Middle Eastern | |||||||

* Ancient

| |||||||

| European | |||||||

| |||||||

| North and South American | |||||||

| |||||||

| Oceanian | |||||||

* Australian

| |||||||

| Asian | |||||||

| |||||||

| African | |||||||

| |||||||

| Related topics | |||||||

* History of science fiction

| |||||||

| {{#invoke:portal-inline|main}} | |||||||

Chinese Prose

Early Chinese prose was deeply influenced by the great philosophical writings of the Hundred Schools of Thought (770–221 B.C.E.). The works of Mo Zi (墨子), Mencius (孟子) and Zhuang Zi (莊子) contain well-reasoned, carefully developed discourses that reveal much stronger organization and style than their predecessors. Mo Zi's polemic prose was built on solid and effective methodological reasoning. Mencius contributed elegant diction and, like Zhuang Zi, relied on comparisons, anecdotes, and allegories. By the 3rd century B.C.E., these writers had developed a simple, concise and economical prose style that served as a model of literary form for over 2,000 years. They were written in Classical Chinese, the language spoken during the Spring and Autumn period.

During the Tang period, the ornate, artificial style of prose developed in previous periods was replaced by a simple, direct, and forceful prose based on examples from the Hundred Schools (see above) and from the Han period, the period in which the great historical works of Sima Tan and Sima Qian were published. This neoclassical style dominated prose writing for the next 800 years. It was exemplified in the work of Han Yu 韓愈 (768–824), a master essayist and strong advocate of a return to Confucian orthodoxy; Han Yu was later listed as one of the "Eight Great Prose Masters of the Tang and Song".

The Song dynasty saw the rise in popularity of "travel record literature" (youji wenxue). Travel literature combined both diary and narrative prose formats, it was practiced by such seasoned travelers as Fan Chengda (1126–1193) and Xu Xiake (1587–1641) and can be seen in the example of Su Shi's Record of Stone Bell Mountain.

After the 14th century, vernacular fiction became popular, at least outside of court circles. Vernacular fiction covered a broader range of subject matter and was longer and more loosely structured than literary fiction. One of the masterpieces of Chinese vernacular fiction is the 18th-century domestic novel Dream of the Red Chamber (紅樓夢).

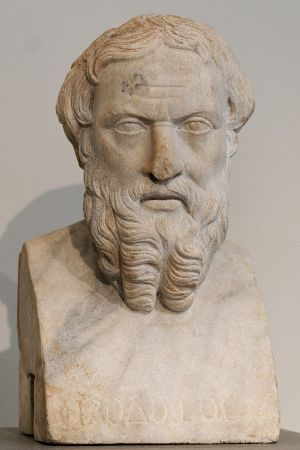

Ancient Greek prose

Greece's classical age produced two of the pioneers of history: Herodotus and Thucydides. Herodotus is commonly called the father of history, and his "History" contains the first truly literary use of prose in Western literature.

Very little has survived of prose fiction from the Hellenistic Era. The Milesiaka by Aristides of Miletos was probably written during the second century B.C.E. The Milesiaka itself has not survived to the present day in its complete form, but various references to it have survived. The book established a whole new genre of so-called "Milesian tales," of which The Golden Ass by the later Roman writer Apuleius is a prime example.[3][4]

The ancient Greek novels Chaereas and Callirhoe[5] by Chariton and Metiochus and Parthenope[6][7] were probably both written during the late first century B.C.E. or early first century AD, during the latter part of the Hellenistic Era. The discovery of several fragments of Lollianos's Phoenician Tale reveal the existence of a genre of ancient Greek picaresque novel.[8]

The Roman Period

The Roman Period was the time when the majority of extant works of Greek prose fiction were composed. The ancient Greek novels Leucippe and Clitophon by Achilles Tatius[9][10] and Daphnis and Chloe by Longus[11] were both probably written during the early second century AD. Daphnis and Chloe, by far the most famous of the five surviving ancient Greek romance novels, is a nostalgic tale of two young lovers growing up in an idealized pastoral environment on the Greek island of Lesbos.[12] The Wonders Beyond Thule by Antonius Diogenes may have also been written during the early second century AD, although scholars are unsure of its exact date. The Wonders Beyond Thule has not survived in its complete form, but a very lengthy summary of it written by Photios I of Constantinople has survived.[13] The Ephesian Tale by Xenophon of Ephesus was probably written during the late second century AD.[11]

The satirist Lucian of Samosata lived during the late second century AD. Lucian's works were incredibly popular during antiquity. Over eighty different writings attributed to Lucian have survived to the present day.[14] Almost all of Lucian's works are written in the heavily Atticized dialect of ancient Greek language prevalent among the well-educated at the time. His book The Syrian Goddess, however, was written in a faux-Ionic dialect, deliberately imitating the dialect and style of Herodotus.[15][16] Lucian's most famous work is the novel A True Story, which some authors have described as the earliest surviving work of science fiction.[17][18] His dialogue The Lover of Lies contains several of the earliest known ghost stories[19] as well as the earliest known version of "The Sorcerer's Apprentice."[20] His letter The Passing of Peregrinus, a ruthless satire against Christians, contains one of the earliest pagan appraisals of early Christianity.[21]

The Aethiopica by Heliodorus of Emesa was probably written during the third century AD.[22] It tells the story of a young Ethiopian princess named Chariclea, who is estranged from her family and goes on many misadventures across the known world.[23] Of all the ancient Greek novels, the one that attained the greatest level of popularity was the Alexander Romance, a fictionalized account of the exploits of Alexander the Great written in the third century AD. Eighty versions of it have survived in twenty-four different languages, attesting that, during the Middle Ages, the novel was nearly as popular as the Bible.[24] Versions of the Alexander Romance were so commonplace in the fourteenth century that Geoffrey Chaucer wrote that "...every wight that hath discrecioun / Hath herd somwhat or al of [Alexander's] fortune."[24]

Latin literature

Early Latin literature

The prose of the period is best known through On Agriculture (160 B.C.E.) by Cato the Elder. Cato wrote the first Latin history of Rome and of other Italian cities.[25] He was the first Roman statesman to put his political speeches in writing as a means of influencing public opinion.

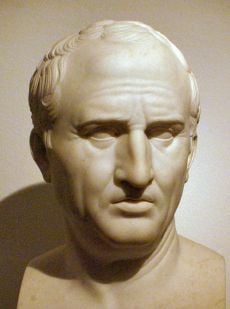

The Golden Age

Cicero has traditionally been considered the master of Latin prose.[26][27] The writing he produced from about 80 B.C.E. until his death in 43 B.C.E. exceeds that of any Latin author whose work survives in terms of quantity and variety of genre and subject matter, as well as possessing unsurpassed stylistic excellence. Cicero's many works can be divided into four groups: (1) letters, (2) rhetorical treatises, (3) philosophical works, and (4) orations. His letters provide detailed information about an important period in Roman history and offer a vivid picture of the public and private life among the Roman governing class. Cicero's works on oratory are our most valuable Latin sources for ancient theories on education and rhetoric. His philosophical works were the basis of moral philosophy during the Middle Ages. His speeches inspired many European political leaders and the founders of the United States.

During the Augustan Age that followed, Livy produced a history of the Roman people in 142 books. Only 35 survived, but they are a major source of information on Rome.[28]

From Latin to the modern vernacular

Latin was a major influence on the development of prose in many European countries. Especially important was the great Roman orator Cicero (106 – 43 B.C.E.).[29] It was the lingua franca among literate Europeans until quite recent times, and the great works of Descartes (1596 – 1650), Francis Bacon (1561 – 1626), and Baruch Spinoza (1632 – 1677) were published in Latin. Among the last important books written primarily in Latin prose were the works of Swedenborg (d. 1772), Linnaeus (d. 1778), Euler (d. 1783), Gauss (d. 1855), and Isaac Newton (d. 1727).

Elizabethan prose

Two of the most important Elizabethan prose writers were John Lyly (1553 or 1554 – 1606) and Thomas Nashe (November 1567 – c. 1601). Lyly is an English writer, poet, dramatist, playwright, and politician, best known for his books Euphues: The Anatomy of Wit (1578) and Euphues and His England (1580). Lyly's mannered literary style, originating in his first books, is known as euphuism. Lyly must also be considered and remembered as a primary influence on the plays of William Shakespeare, and in particular the romantic comedies. Lyly's play Love's Metamorphosis is a large influence on Love's Labour's Lost,[30] and Gallathea is a possible source for other plays.[31] After the lyrical Richard II, written almost entirely in verse, Shakespeare introduced prose comedy into the histories of the late 1590s, Henry IV, parts 1 and 2, and Henry V.

Nashe is considered the greatest of the English Elizabethan pamphleteers.[32] He was a playwright, poet, and satirist, who is best known for his novel The Unfortunate Traveller.[33]

Augustan era prose

Restoration era prose

Prose in the Restoration period is dominated by Christian religious writing, but the Restoration also saw the beginnings of two genres that would dominate later periods: fiction and journalism. Religious writing often strayed into political and economic writing; just as political and economic writing implied or directly addressed religion.

Ottoman Empire prose

Ottoman prose did not contain any examples of fiction; that is, there were no counterparts to, for instance, the European romance, short story, or novel (though analogous genres did, to some extent, exist in both the Turkish folk tradition and in Divan poetry). Roughly speaking, the prose of the Ottoman Empire can be divided along the lines of two broad periods: early Ottoman prose, written prior to the 19th century CE and exclusively nonfictional in nature; and later Ottoman prose, which extended from the mid-19th century Tanzimat period of reform to the final fall of the Ottoman Empire in 1922, and in which prose fiction was first introduced.

Qualities

Prose usually lacks the more formal metrical structure of the verses found in traditional poetry. It comprises full grammatical sentences (other than in stream of consciousness narrative), and paragraphs, while poetry usually involves a metrical or rhyming scheme. Some works of prose make use of rhythm and verbal music. Verse is normally more systematic or formulaic, while prose is closer to both ordinary, and conversational speech.

In Molière's play Le Bourgeois gentilhomme the character Monsieur Jourdain asked for something to be written in neither verse nor prose, to which a philosophy master replies: "there is no other way to express oneself than with prose or verse," for the simple reason that "everything that is not prose is verse, and everything that is not verse is prose."[34]

American novelist Truman Capote, in an interview, commented on prose style as follows:

<Blockquote<I believe a story can be wrecked by a faulty rhythm in a sentence— especially if it occurs toward the end—or a mistake in paragraphing, even punctuation. Henry James is the maestro of the semicolon. Hemingway is a first-rate paragrapher. From the point of view of ear, Virginia Woolf never wrote a bad sentence. I don't mean to imply that I successfully practice what I preach. I try, that's all.[35]

Types

Many types of prose exist, which include those used in works of nonfiction, prose poem,[36] alliterative prose and prose fiction.

- A prose poem – is a composition in prose that has some of the qualities of a poem.[37]

- Haikai prose – combines haiku and prose.

- Prosimetrum – is a poetic composition which exploits a combination of prose and verse (metrum);[38] in particular, it is a text composed in alternating segments of prose and verse.[39] It is widely found in Western and Eastern literature.[39]

- Purple prose – is prose that is so extravagant, ornate, or flowery as to break the flow and draw excessive attention to itself.[40]

Divisions

Prose is divided into two main divisions:

- Fiction

- Non fiction

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ prose (n.). Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ Eliot, T. S. Poetry & Prose: The Chapbook, Poetry Bookshop London, 1921.

- ↑ (1968) Lucius Madaurensis. Phoenix 22 (2): 143–157.

- ↑ (1960) The Golden Ass. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-20036-9.

- ↑ Edmund P. Cueva (Fall 1996). "Plutarch's Ariadne in Chariton's Chaereas and Callirhoe". American Journal of Philology. 117 (3): 473–484. Digital object identifier (DOI): 10.1353/ajp.1996.0045 .

- ↑ Cf. Thomas Hägg, 'The Oriental Reception of Greek Novels: A Survey with Some Preliminary Considerations', Symbolae Osloenses, 61 (1986), 99–131 (p. 106), Digital object identifier (DOI): 10.1080/00397678608590800 .

- ↑ Thomas Hägg and Bo Utas, The Virgin and Her Lover: Fragments of an Ancient Greek Novel and a Persian Epic Poem. Brill Studies in Middle Eastern Literatures, 30 (Leiden: Brill, 2003), p. 1.

- ↑ (1989) Collected Ancient Greek Novels. Berkeley: University of California Press, 809–810. ISBN 0-520-04306-5.

- ↑ The "early dating of P.Oxy 3836 holds, Achilles Tatius' novel must have been written 'nearer 120 than 150'" Albert Henrichs, Culture In Pieces: Essays on Ancient Texts in Honour of Peter Parsons, eds. Dirk Obbink, Richard Rutherford, Oxford University Press, 2011, p. 309, n. 29 Template:ISBN, 9780199292011

- ↑ "the use (albeit mid and erratic) of the Attic dialect suggest a date a little earlier [than mid-2nd century] in the same century." The Greek Novel: Oxford Bibliographies Online Research Guide Oxford University Press, 2010, p. 7 Template:ISBN, 9780199803033

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Longus; Xenophon of Ephesus (2009), Henderson, Jeffery, ed., Anthia and Habrocomes (translation), Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, pp. 69 & 127, Template:ISBN

- ↑ Richard Hunter (1996). "Longus, Daphnis and Chloe", in Gareth L. Schmeling: The Novel in the Ancient World. Brill, 361–86. ISBN 90-04-09630-2.

- ↑ J.R. Morgan. Lucian's True Histories and the Wonders Beyond Thule of Antonius Diogenes. The Classical Quarterly (New Series), 35, pp 475–490 Digital object identifier (DOI): 10.1017/S0009838800040313 .

- ↑ Moeser, Marion (Dec 15, 2002). The Anecdote in Mark, the Classical World and the Rabbis: A Study of Brief Stories in the Demonax, The Mishnah, and Mark 8:27–10:45. A&C Black. p. 88. Template:ISBN. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ Lightfoot, De Dea Syria (2003)

- ↑ Lucinda Dirven, "The Author of De Dea Syria and his Cultural Heritage", Numen 44.2 (May 1997), pp. 153–179.

- ↑ Greg Grewell: "Colonizing the Universe: Science Fictions Then, Now, and in the (Imagined) Future", Rocky Mountain Review of Language and Literature, Vol. 55, No. 2 (2001), pp. 25–47 (30f.)

- ↑ Fredericks, S.C.: "Lucian's True History as SF", Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 3, No. 1 (March 1976), pp. 49–60

- ↑ "The Doubter" by Lucian in Roger Lancelyn Green (1970) Thirteen Uncanny Tales. London, Dent: 14–21; and Finucane, pg 26.

- ↑ George Luck "Witches and Sorcerers in Classical Literature", p. 141, Witchcraft and Magic in Europe: Ancient Greece And Rome edited by Bengt Ankarloo and Stuart Clark Template:ISBN

- ↑ Robert E. Van Voorst, Jesus outside the New Testament, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2000.

- ↑ Holzberg, Niklas. The Ancient Novel. 1995. p. 78

- ↑ Bowersock, Glanwill W. The Aethiopica of Heliodorus and the Historia Augusta. In: Historiae Augustae Colloquia n.s. 2, Colloquium Genevense 1991. p. 43.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 (1989) Collected Ancient Greek Novels. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04306-5.

- ↑ Mehl, Andreas. Roman Historiography. Wiley-Blackwell, 2010. p 52. Web. 18 October 2011.

- ↑ Charles W. Eliot (2004). Letters of Marcus Tullius Cicero and Letters of Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus: Part 9 Harvard Classics. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 9780766182042.

- ↑ Nettleship, Henry; Haverfield, F. Lectures and Essays: Second Series. Cambridge University Press, 2010. p. 105. Web. 18 October 2011.

- ↑ Cary, Max; Haarhoff, Theodore Johannes. Life and thought in the Greek and Roman world. Taylor & Francis, 1985. p. 268. Web. 15 October 2011.

- ↑ "Literature", Encyclopaedia Britannica. online

- ↑ Kerrigan, J. ed. "Love's Labours Lost", New Penguin Shakespeare, Harmondsworth 1982, Template:ISBN;

- ↑ "John Lilly and Shakespeare", by C. C. Hense in the Jahrbuch der deutschen Shakesp. Gesellschaft, vols. vii and viii (1872, 1873).

- ↑ "'Faustus' and the Politics of Magic", 8 March 1990, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ "Sex and books: London's most erotic writers", Time Out, 28 February 2008.

- ↑ "Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme," |work=English translation accessible via Project Gutenberg

- ↑ Pati Hill, "Truman Capote, The Art of Fiction No. 17," The Paris Review (Spring-Summer 1957).

- ↑ Lehman, David (2008). Great American Prose Poems. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1439105115.

- ↑ Template:Cite dictionary

- ↑ Braund, Susanna. "Prosimetrum". In Cancil, Hubert, and Helmuth Schneider, eds. Brill's New Pauly. Brill Online, 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Brogan, T.V.F. "Prosimetrum". In Green et al., pp. 1115–1116.

- ↑ A Word a Day – purple prose.

Further reading

- Patterson, William Morrison, Rhythm of Prose, Columbia University Press, 1917.

- Kuiper, Kathleen (2011). Prose: Literary Terms and Concepts. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1615304943. 244 pages.

- Shklovsky, Viktor (1991). Theory of Prose. Dalkey Archive Press. ISBN 0916583643. 216 pages.

External links

{{#invoke:subject bar|main}}

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.