Difference between revisions of "Ogre" - New World Encyclopedia

Nick Perez (talk | contribs) |

|||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

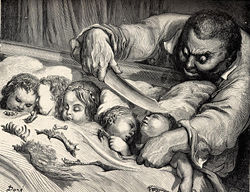

[[Image:Poucet10.jpg|thumb|250px|''The Ogre from [[Hop o' My Thumb]]'' illustrated by [[Gustave Doré]]]] | [[Image:Poucet10.jpg|thumb|250px|''The Ogre from [[Hop o' My Thumb]]'' illustrated by [[Gustave Doré]]]] | ||

| − | An '''ogre''' (feminine: ''ogress'') is a large and hideous [[humanoid]] [[monster]], often found in [[fairy | + | An '''ogre''' (feminine: ''ogress'') is a large and hideous [[humanoid]] [[monster]], a [[mythical creature]] often found in [[fairy tale]]s and [[folklore]]. While commonly depicted as an unintelligent and clumsy enemy, dangerous in that it feeds on its human victims, some authors choose to show them in a somewhat brighter light, saying they are both shy and reclusive. Today, variants of ogres can be found in modern [[fantasy]] sub-culture, such as in games and literature. |

==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| − | The word '''ogre''' is spelled the same in [[English language|English]] as it is in [[French language|French]], where it originates. It gained popularity | + | The word '''ogre''' is spelled the same in [[English language|English]] as it is in [[French language|French]], where it originates. The word ogre is quite possibly a derivative of the [[Italian language|Italian]] ''orgo'', which is a later function of ''orco'', which translates as "demon."<ref name=oed> (1971) ''Oxford English Dictionary'' ISBN 019861117X </ref> It probably ultimately derives from the [[Latin]] [[Orcus]], Roman god of the underworld.<ref>[http://www.answers.com/ogre Ogre] answers.com Retrieved July 11, 2007.</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | The idea of this type of [[mythical creature]] gained popularity with its use by French author [[Charles Perrault]] with his 1696 publication ''Tales of Mother Goose'', which laid foundations for a new literary genre, the [[fairy tale]], and whose best known tales include ''Le Chat botté'' (Puss in Boots) and ''Le Petit Poucet'' (Hop o' My Thumb) both of which feature ogres. In more modern times, the word is sometimes used as an adjective: ''Ogreish'' refers to anyone who possesses characters of an ogre and is often used in a negative context.<ref name=oed/> | ||

==Description== | ==Description== | ||

| − | Ogres are often characterized by their large, often disproportionate features: depending upon the culture, ogres can | + | Ogres are often characterized by their large, often disproportionate features: depending upon the culture, ogres can be several times the size of a human being, or only a few feet taller. They are usually solidly built, with rounded heads, a large stomach and abundant and hirsute hair and beard. Their skin is said to be rough and a dull [[earth]]-tone in [[Europe]], while in [[Asia]] their skin can sometimes be a vibrant red or orange. They often have large mouths full of prominent teeth, are distinguishable for their ugliness, and are accompanied by a horrific smell. |

==Origins== | ==Origins== | ||

| − | The idea of the ogre often overlaps with that of [[giant]]s and [[troll]]s, so it is conceivable that all three mythical | + | The idea of the ogre often overlaps with that of [[giant]]s and [[troll]]s, so it is conceivable that all three [[mythical creature]]s have similar origins. Some scientists, such as Spanish [[paleoanthropology|paleoanthropologist]] [[Juan Luis Arsuaga]], have theorized based on [[fossil]] evidence that [[Neanderthal]]s and [[Cro-Magnon]]s occupied the same area of [[Europe]] at the same time.<ref>"The Neanderthal's Necklace." Four Walls Eight Windows. 2002.</ref> The distinguished Swedish-speaking [[Finland|Finnish]] [[paleontology|paleontologist]] [[Björn Kurtén]] has entertained and expanded this theory to determine that trolls and ogres are a distant memory of an encounter with Neanderthals by our Cro-Magnon ancestors some 40,000 years ago during their migration into northern Europe.<ref>Alba, Stockholm. 1978. "Dance of The Tiger: An Ice Age Story" ("Den Svarta Tigern").</ref> As new fossil evidence comes to light in Asia, it is conceivable that Asian beliefs in ogres could also be contributed to a collectively shared memory of human ancestors. |

| − | Another explanation for the ogre myth is that the ogres represent the remains of the forefather-cult which was ubiquitous in [[Scandinavia]] until the introduction of [[Christianity]] in the tenth and eleventh centuries. In this cult the forefathers were worshiped in sacred groves, by altars, or by grave mounds. | + | Another explanation for the ogre myth is that the ogres represent the remains of the forefather-cult which was ubiquitous in [[Scandinavia]] until the introduction of [[Christianity]] in the tenth and eleventh centuries. In this cult the forefathers were worshiped in sacred groves, by altars, or by grave mounds. They believed that after death a person's spirit continued to live on, or near, the family farm. This particularly applied to the "founding-father" of the estate, over whose body a large ''haugr'', or burial mound, was constructed.<ref>[http://www.orkneyjar.com/folklore/hogboon/index.html The Hogboon - Orkney's Mound Dweller] Retrieved July 11, 2007.</ref> This revered ancestor's spirit remained "living" in his mound, a guardian over the property. This guardian was treated with an awed, if not fearful, respect. He resented the slightest liberty that might be taken on, or near, his resting place. Children playing nearby would cause great outbursts, hence the idea that they ate children. With the introduction of Christianity however, the religious elite sought to [[demon]]ize the [[paganism|pagan]] cult, and denounced the all worship or respect for such "mound-dwelling" spirits as evil. |

==Ogres in various cultures== | ==Ogres in various cultures== | ||

[[Image:Oni2WP.jpg|thumb|left|200px|A Japanese ''aka-oni'', or "red ogre," vanquishes demons at an [[onsen]] in [[Beppu, Oita|Beppu]]]] | [[Image:Oni2WP.jpg|thumb|left|200px|A Japanese ''aka-oni'', or "red ogre," vanquishes demons at an [[onsen]] in [[Beppu, Oita|Beppu]]]] | ||

| − | According to the [[folklore]] and [[mythology]] of the peoples of [[Northern Europe]], ogres live in the far corners of forests and mountains, sometimes even in castles. They are almost always incredibly large and stupid, being easily out-witted by humans. They are not always malicious | + | According to the [[folklore]] and [[mythology]] of the peoples of [[Northern Europe]], ogres live in the far corners of forests and mountains, sometimes even in castles. They are almost always incredibly large and stupid, being easily out-witted by humans. They are not always malicious; while there are stories of ogres that [[kidnap]] and eat children, terrorize villages, and even guard hordes of treasures or mystical secrets, they are sometimes considered merely shy and reclusive. |

Certain Asian cultures have stories with creatures resembling ogres. Many [[Japan]]ese fairy tales inspired by [[Japanese folklore and mythology|mythology]] and [[religion]] include the ''[[Oni (Japanese folklore)|oni]]'', a creature popularly associated with the ogre. ''[[Momotaro]]'' ("Peach Boy"), is one example, including the appearance of blue, red, and yellow oni with horns and iron clubs. | Certain Asian cultures have stories with creatures resembling ogres. Many [[Japan]]ese fairy tales inspired by [[Japanese folklore and mythology|mythology]] and [[religion]] include the ''[[Oni (Japanese folklore)|oni]]'', a creature popularly associated with the ogre. ''[[Momotaro]]'' ("Peach Boy"), is one example, including the appearance of blue, red, and yellow oni with horns and iron clubs. | ||

| Line 27: | Line 29: | ||

Ogres also appear in [[tribal society|tribal cultures]]. [[Pygmy]] mythology includes the tale of Negoogunogumbar, an ogre who devours children. Many Ogre-like creatures are also found in [[Indigenous peoples of the Americas|Native American]] tribal traditions and are usually in the form of man-eating giants. They are often linked to legends of [[bigfoot]]. | Ogres also appear in [[tribal society|tribal cultures]]. [[Pygmy]] mythology includes the tale of Negoogunogumbar, an ogre who devours children. Many Ogre-like creatures are also found in [[Indigenous peoples of the Americas|Native American]] tribal traditions and are usually in the form of man-eating giants. They are often linked to legends of [[bigfoot]]. | ||

| − | The idea of the ogre | + | The idea of the ogre may also be used metaphorically in contemporary culture, as a dictator who controls and exploits others, and thus devours them, or as a seducer devouring his or her victims. This type of usage is seen in the association of ogres with [[Nazism|Nazis]] made in [[Michael Tournier|Michel Tournier's]] 1970 novel ''Le Roi des Aulnes'' (''The Erl King'' or ''The Ogre''). |

==Pop Culture== | ==Pop Culture== | ||

[[Image:Lechatbotte4.jpg|thumb|250 px|"Puss in Boots" outwits the Ogre by Gustave Doré]] | [[Image:Lechatbotte4.jpg|thumb|250 px|"Puss in Boots" outwits the Ogre by Gustave Doré]] | ||

| − | Literature for children has | + | Literature for children has numerous tales mentioning ogres and [[kidnap]]ped [[princess]]es who were rescued by valiant knights and, sometimes, [[peasant]]s. In the classic tale, ''[[Puss in Boots]]'', a [[cat]] outwits a shape-changing ogre. |

| − | Other [[fairy tale]]s | + | Other [[fairy tale]]s involving ogres include ''Motiratika'', ''Tritill, Litill, and the Birds'', ''Don Firriulieddu'', ''Snow-White-Fire-Red'', ''Shortshanks'', ''Thirteenth'', and ''Don Joseph Pear''. Ogres are also popular in [[fantasy fiction]], such as [[C.S. Lewis]]'s ''[[The Chronicles of Narnia]]''. Piers Anthony's ''[[Xantha]]'' series, the ''[[Spiderwick Chronicles]]'', [[Tamora Pierce]]'s ''[[The Tortall Universe]]'', and [[Ruth Manning-Sanders]]' ''[[A Book of Ogres and Trolls]]'' are just a few of the popular works of fiction that incorporate ogres in their stories. |

| − | Ogres appear in many popular [[fantasy]] [[role-playing]] and video games series such as ''[[Dungeons & Dragons]]'', ''[[RuneScape]]'', ''[[Final Fantasy]]'', ''[[Warhammer Fantasy]]'', ''[[Warcraft]]'', ''[[Magic: The Gathering]]'', ''[[The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion]]'', [[Ogre Battle]], and ''[[EverQuest]]''. | + | Ogres also appear in many popular [[fantasy]] [[role-playing]] and video games series such as ''[[Dungeons & Dragons]]'', ''[[RuneScape]]'', ''[[Final Fantasy]]'', ''[[Warhammer Fantasy]]'', ''[[Warcraft]]'', ''[[Magic: The Gathering]]'', ''[[The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion]]'', [[Ogre Battle]], and ''[[EverQuest]]''. |

==Footnotes== | ==Footnotes== | ||

| Line 42: | Line 44: | ||

==Resources== | ==Resources== | ||

* Rose, Carol. ''Giants, Monsters, & Dragons: An Encyclopedia of Folklore, Legend, and Myth''. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001. ISBN 0-393-32211-4 | * Rose, Carol. ''Giants, Monsters, & Dragons: An Encyclopedia of Folklore, Legend, and Myth''. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001. ISBN 0-393-32211-4 | ||

| − | * South, Malcom, ed. ''Mythical and Fabulous Creatures: A Source Book and Research Guide.'' Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1987. Reprint, New York: Peter Bedrick Books, 1988. | + | * South, Malcom, ed. ''Mythical and Fabulous Creatures: A Source Book and Research Guide.'' Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1987. Reprint, New York: Peter Bedrick Books, 1988. ISBN 0-87226-208-1 |

| − | * "Ogre." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2006. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 15 | + | * "Ogre." ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. 2006. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved May 15, 2006 <http://www.search.eb.com/eb/article-9125639> |

* [http://www.surlalunefairytales.com/authors/perrault.html SurLaLune Fairy Tale Pages: Fairy Tales of Charles Perrault] Retrieved July 5, 2007. | * [http://www.surlalunefairytales.com/authors/perrault.html SurLaLune Fairy Tale Pages: Fairy Tales of Charles Perrault] Retrieved July 5, 2007. | ||

{{Credits|Ogre|115041668|}} | {{Credits|Ogre|115041668|}} | ||

Revision as of 15:10, 11 July 2007

An ogre (feminine: ogress) is a large and hideous humanoid monster, a mythical creature often found in fairy tales and folklore. While commonly depicted as an unintelligent and clumsy enemy, dangerous in that it feeds on its human victims, some authors choose to show them in a somewhat brighter light, saying they are both shy and reclusive. Today, variants of ogres can be found in modern fantasy sub-culture, such as in games and literature.

Etymology

The word ogre is spelled the same in English as it is in French, where it originates. The word ogre is quite possibly a derivative of the Italian orgo, which is a later function of orco, which translates as "demon."[1] It probably ultimately derives from the Latin Orcus, Roman god of the underworld.[2]

The idea of this type of mythical creature gained popularity with its use by French author Charles Perrault with his 1696 publication Tales of Mother Goose, which laid foundations for a new literary genre, the fairy tale, and whose best known tales include Le Chat botté (Puss in Boots) and Le Petit Poucet (Hop o' My Thumb) both of which feature ogres. In more modern times, the word is sometimes used as an adjective: Ogreish refers to anyone who possesses characters of an ogre and is often used in a negative context.[1]

Description

Ogres are often characterized by their large, often disproportionate features: depending upon the culture, ogres can be several times the size of a human being, or only a few feet taller. They are usually solidly built, with rounded heads, a large stomach and abundant and hirsute hair and beard. Their skin is said to be rough and a dull earth-tone in Europe, while in Asia their skin can sometimes be a vibrant red or orange. They often have large mouths full of prominent teeth, are distinguishable for their ugliness, and are accompanied by a horrific smell.

Origins

The idea of the ogre often overlaps with that of giants and trolls, so it is conceivable that all three mythical creatures have similar origins. Some scientists, such as Spanish paleoanthropologist Juan Luis Arsuaga, have theorized based on fossil evidence that Neanderthals and Cro-Magnons occupied the same area of Europe at the same time.[3] The distinguished Swedish-speaking Finnish paleontologist Björn Kurtén has entertained and expanded this theory to determine that trolls and ogres are a distant memory of an encounter with Neanderthals by our Cro-Magnon ancestors some 40,000 years ago during their migration into northern Europe.[4] As new fossil evidence comes to light in Asia, it is conceivable that Asian beliefs in ogres could also be contributed to a collectively shared memory of human ancestors.

Another explanation for the ogre myth is that the ogres represent the remains of the forefather-cult which was ubiquitous in Scandinavia until the introduction of Christianity in the tenth and eleventh centuries. In this cult the forefathers were worshiped in sacred groves, by altars, or by grave mounds. They believed that after death a person's spirit continued to live on, or near, the family farm. This particularly applied to the "founding-father" of the estate, over whose body a large haugr, or burial mound, was constructed.[5] This revered ancestor's spirit remained "living" in his mound, a guardian over the property. This guardian was treated with an awed, if not fearful, respect. He resented the slightest liberty that might be taken on, or near, his resting place. Children playing nearby would cause great outbursts, hence the idea that they ate children. With the introduction of Christianity however, the religious elite sought to demonize the pagan cult, and denounced the all worship or respect for such "mound-dwelling" spirits as evil.

Ogres in various cultures

According to the folklore and mythology of the peoples of Northern Europe, ogres live in the far corners of forests and mountains, sometimes even in castles. They are almost always incredibly large and stupid, being easily out-witted by humans. They are not always malicious; while there are stories of ogres that kidnap and eat children, terrorize villages, and even guard hordes of treasures or mystical secrets, they are sometimes considered merely shy and reclusive.

Certain Asian cultures have stories with creatures resembling ogres. Many Japanese fairy tales inspired by mythology and religion include the oni, a creature popularly associated with the ogre. Momotaro ("Peach Boy"), is one example, including the appearance of blue, red, and yellow oni with horns and iron clubs.

Ogres also appear in tribal cultures. Pygmy mythology includes the tale of Negoogunogumbar, an ogre who devours children. Many Ogre-like creatures are also found in Native American tribal traditions and are usually in the form of man-eating giants. They are often linked to legends of bigfoot.

The idea of the ogre may also be used metaphorically in contemporary culture, as a dictator who controls and exploits others, and thus devours them, or as a seducer devouring his or her victims. This type of usage is seen in the association of ogres with Nazis made in Michel Tournier's 1970 novel Le Roi des Aulnes (The Erl King or The Ogre).

Pop Culture

Literature for children has numerous tales mentioning ogres and kidnapped princesses who were rescued by valiant knights and, sometimes, peasants. In the classic tale, Puss in Boots, a cat outwits a shape-changing ogre.

Other fairy tales involving ogres include Motiratika, Tritill, Litill, and the Birds, Don Firriulieddu, Snow-White-Fire-Red, Shortshanks, Thirteenth, and Don Joseph Pear. Ogres are also popular in fantasy fiction, such as C.S. Lewis's The Chronicles of Narnia. Piers Anthony's Xantha series, the Spiderwick Chronicles, Tamora Pierce's The Tortall Universe, and Ruth Manning-Sanders' A Book of Ogres and Trolls are just a few of the popular works of fiction that incorporate ogres in their stories.

Ogres also appear in many popular fantasy role-playing and video games series such as Dungeons & Dragons, RuneScape, Final Fantasy, Warhammer Fantasy, Warcraft, Magic: The Gathering, The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion, Ogre Battle, and EverQuest.

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 (1971) Oxford English Dictionary ISBN 019861117X

- ↑ Ogre answers.com Retrieved July 11, 2007.

- ↑ "The Neanderthal's Necklace." Four Walls Eight Windows. 2002.

- ↑ Alba, Stockholm. 1978. "Dance of The Tiger: An Ice Age Story" ("Den Svarta Tigern").

- ↑ The Hogboon - Orkney's Mound Dweller Retrieved July 11, 2007.

Resources

- Rose, Carol. Giants, Monsters, & Dragons: An Encyclopedia of Folklore, Legend, and Myth. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001. ISBN 0-393-32211-4

- South, Malcom, ed. Mythical and Fabulous Creatures: A Source Book and Research Guide. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1987. Reprint, New York: Peter Bedrick Books, 1988. ISBN 0-87226-208-1

- "Ogre." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2006. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved May 15, 2006 <http://www.search.eb.com/eb/article-9125639>

- SurLaLune Fairy Tale Pages: Fairy Tales of Charles Perrault Retrieved July 5, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.