Mid-Autumn Festival

| Mid-Autumn Festival | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mid-Autumn Festival decorations in Beijing | |

| Official name | 中秋節 (Zhōngqiū Jié in China, Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia; "Tiong Chiu Jiet" in Hokkien-speaking areas, Jūng-chāu Jit in Hong Kong and Macau) Tết Trung Thu (Vietnam) Chuseok 추석/秋夕 (Korea) Tsukimi 月見 (Japan) |

| Observed by | China, Taiwan, Korea, Japan, Singapore, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, Philippines, Cambodia, Thailand |

| Significance | Celebrates the end of the autumn harvest |

| Date | 15th day of the 8th lunar month |

| Observances | Consumption of mooncakes Consumption of cassia wine |

| Related to | Chuseok (in Korea), Tsukimi (in Japan), Uposatha of Ashvini/Krittika (similar festivals that generally occur on the same day in Cambodia, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand) |

The Mid-Autumn Festival is a harvest festival celebrated notably by the Chinese and Vietnamese people. It relates to Chuseok (in Korea) and Tsukimi (in Japan). The festival is held on the 15th day of the 8th month of the lunar calendar with a full moon at night, corresponding to mid September to early October of the Gregorian calendar.

Mooncakes, a rich pastry typically filled with sweet-bean or lotus-seed paste, are traditionally eaten during the festival.

Names

The Mid-Autumn Festival is also known by other names, such as:

- Moon Festival or Harvest Moon Festival, because of the celebration's association with the full moon on this night, as well as the traditions of moon worship and moon viewing.

- Zhōngqiū Jié (中秋节), is the official name in Mandarin.

- Jūng-chāu Jit (中秋節), official name in Cantonese.

- Reunion Festival, in earlier times, a woman in China took this occasion to visit her parents before returning to celebrate with her husband and his parents.[1]

- Tết Trung Thu, official name in Vietnamese.

- Children's Festival, in Vietnam, because of the emphasis on the celebration of children.[2]

- Chuseok (추석/秋夕; Autumn Eve), Korean variant of the Mid-Autumn Festival celebrated on the same day in the lunar calendar.

- Tsukimi (月見; Moon-Viewing), Japanese variant of the Mid-Autumn Festival celebrated on the same day in the lunar calendar.

- Lantern Festival, a term sometimes used in Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia, which is not to be confused with the Lantern Festival in China that occurs on the 15th day of the first month of the Chinese calendar.

Meanings of the festival

The festival celebrates three fundamental concepts that are closely connected:

- Gathering, such as family and friends coming together, or harvesting crops for the festival. It is said the moon is the brightest and roundest on this day which means family reunion. Consequently, this is the main reason why the festival is thought to be important.

- Thanksgiving, to give thanks for the harvest, or for harmonious unions

- Praying (asking for conceptual or material satisfaction), such as for babies, a spouse, beauty, longevity, or for a good future

Traditions and myths surrounding the festival are formed around these concepts, although traditions have changed over time due to changes in technology, science, economy, culture, and religion.[3]

Origins and development

The Chinese have celebrated the harvest during the autumn full moon since the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 B.C.E.).[3] The term mid-autumn (中秋) first appeared in Rites of Zhou, a written collection of rituals of the Western Zhou dynasty (1046–771 B.C.E.).[4]

The celebration as a festival only started to gain popularity during the early Tang dynasty (618–907 C.E.).[4] One legend explains that Emperor Xuanzong of Tang started to hold formal celebrations in his palace after having explored the Moon-Palace.[3]

For the Baiyue peoples, the harvest time commemorated the dragon who brought rain for the crops.[5]

Empress Dowager Cixi (late nineteenth century) enjoyed celebrating the Mid-Autumn Festival so much that she would spend the period between the thirteenth and seventeenth day of the eighth month staging elaborate rituals.[6]

Moon worship

An important part of the festival celebration is moon worship. The ancient Chinese believed in rejuvenation being associated with the moon and water, and connected this concept to the menstruation of women, calling it "monthly water."[1] The Zhuang people, for example, have an ancient fable saying the sun and moon are a couple and the stars are their children, and when the moon is pregnant, it becomes round, and then becomes crescent after giving birth to a child. These beliefs made it popular among women to worship and give offerings to the moon on this evening.[1]

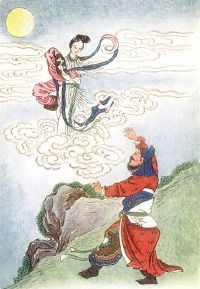

Offerings are also made to a more well-known lunar deity, Chang'e, known as the Moon Goddess of Immortality. The myths associated with Chang'e explain the origin of moon worship during this day:

In the ancient past, there was a hero named Hou Yi who was excellent at archery. His wife was Chang'e. One year, the ten suns rose in the sky together, causing great disaster to the people. Yi shot down nine of the suns and left only one to provide light. An immortal admired Yi and sent him the elixir of immortality. Yi did not want to leave Chang'e and be immortal without her, so he let Chang'e keep the elixir. However, Peng Meng, one of his apprentices, knew this secret. So, on the fifteenth of August in the lunar calendar, when Yi went hunting, Peng Meng broke into Yi's house and forced Chang'e to give the elixir to him. Chang'e refused to do so. Instead, she swallowed it and flew into the sky. Since she loved her husband and hoped to live nearby, she chose the moon for her residence. When Yi came back and learned what had happened, he felt so sad that he displayed the fruits and cakes Chang'e liked in the yard and gave sacrifices to his wife. People soon learned about these activities, and since they also were sympathetic to Chang'e they participated in these sacrifices with Yi.[7]

An alternate common version of the myth also relates to moon worship:

After the hero Houyi shot down nine of the ten suns, he was pronounced king by the thankful people. However, he soon became a conceited and tyrannical ruler. In order to live long without death, he asked for the elixir from Xiwangmu. But his wife, Chang'e, stole it on the fifteenth of August because she did not want the cruel king to live long and hurt more people. She took the magic potion to prevent her husband from becoming immortal. Houyi was so angry when discovered that Chang'e took the elixir, he shot at his wife as she flew toward the moon, though he missed. Chang'e fled to the moon and became the spirit of the moon. Houyi died soon because he was overcome with great anger. Thereafter, people offer a sacrifice to Chang'e on every lunar fifteenth of August to commemorate Chang'e's action.[7]

Contemporary celebration

The Mid-Autumn Festival is held on the 15th day of the eighth month in the Chinese calendar—essentially the night of a full moon—which falls near the Autumnal Equinox (on a day between September 8 and October 7 in the Gregorian calendar).

Traditionally the festival is a time to enjoy the successful reaping of rice and wheat with food offerings made in honor of the moon. Today, it is still an occasion for outdoor reunions among friends and relatives to eat mooncakes and watch the moon, a symbol of harmony and unity. During a year of a solar eclipse, it is typical for governmental offices, banks, and schools to close extra days in order to enjoy the extended celestial celebration an eclipse brings.[8] The festival is celebrated with many cultural or regional customs, among them:

- Burning incense in reverence to deities including Chang'e.

- Performance of dragon and lion dances, popular in southern China and Hong Kong.[9]

Lanterns

A notable part of celebrating the holiday is the carrying of brightly lit lanterns, lighting lanterns on towers, or floating sky lanterns. Another tradition involving lanterns is to write riddles on them and have other people try to guess the answers.[10]

It is difficult to discern the original purpose of lanterns in connection to the festival, but it is certain that lanterns were not used in conjunction with moon-worship prior to the Tang dynasty.[3] Traditionally, the lantern has been used to symbolize fertility, and functioned mainly as a toy and decoration. But today the lantern has come to symbolize the festival itself. In the old days, lanterns were made in the image of natural things, myths, and local cultures. Over time, a greater variety of lanterns could be found as local cultures became influenced by their neighbors.[3]

As China gradually evolved from an agrarian society to a mixed agrarian-commercial one, traditions from other festivals began to be transmitted into the Mid-Autumn Festival, such as the putting of lanterns on rivers to guide the spirits of the drowned as practiced during the Ghost Festival, which is observed a month before. Hong Kong fishermen during the Qing dynasty, for example, would put up lanterns on their boats for the Ghost Festival and keep the lanterns up until Mid-Autumn Festival.[3]

In Vietnam, children participate in parades in the dark under the full moon with lanterns of various forms, shapes, and colors. Traditionally, lanterns signify the wish for the sun's light and warmth to return after winter.[11] In addition to carrying lanterns, the children also don elaborate masks. Handcrafted shadow lanterns were an important part of Mid-Autumn displays since the twelfth-century Lý dynasty, often of historical figures from Vietnamese history.[5] Handcrafted lantern-making has declined in modern times due to the availability of mass-produced plastic lanterns, which often depict internationally recognized characters such as Pokémon's Pikachu, Disney characters, SpongeBob SquarePants, and Hello Kitty.

Mooncakes

Mooncakes, a rich pastry typically filled with sweet-bean or lotus-seed paste, are traditionally eaten during the festival.[12][13][14][15][16]

Making and sharing mooncakes is one of the hallmark traditions of this festival. In Chinese culture, a round shape symbolizes completeness and reunion. Thus, the sharing and eating of round mooncakes among family members during the week of the festival signifies the completeness and unity of families.[17] In some areas of China, there is a tradition of making mooncakes during the night of the Mid-Autumn Festival.[18] The senior person in that household would cut the mooncakes into pieces and distribute them to each family member, signifying family reunion.[18] In modern times, however, making mooncakes at home has given way to the more popular custom of giving mooncakes to family members, although the meaning of maintaining familial unity remains.[citation needed]

Although typical mooncakes can be around a few centimetres in diameter, imperial chefs have made some as large as 8 meters in diameter, with its surface pressed with designs of Chang'e, cassia trees, or the Moon-Palace.[8] One tradition is to pile 13 mooncakes on top of each other to mimic a pagoda, the number 13 being chosen to represent the 13 months in a full lunar year.[8] The spectacle of making very large mooncakes continues in modern China.[19]

According to Chinese folklore, a Turpan businessman offered cakes to Emperor Taizong of Tang in his victory against the Xiongnu on the fifteenth day of the eighth lunar month. Taizong took the round cakes and pointed to the moon with a smile, saying, "I'd like to invite the toad to enjoy the hú (胡) cake." After sharing the cakes with his ministers, the custom of eating these hú cakes spread throughout the country.[20] Eventually these became known as mooncakes. Although the legend explains the beginnings of mooncake-giving, its popularity and ties to the festival began during the Song dynasty (906–1279 C.E.).[3]

Another popular legend concerns the Han Chinese's uprising against the ruling Mongols at the end of the Yuan dynasty (1280–1368 C.E.), in which the Han Chinese used traditional mooncakes to conceal the message that they were to rebel on Mid-Autumn Day.[21] Because of strict controls upon Han Chinese families imposed by the Mongols in which only 1 out of every 10 households was allowed to own a knife guarded by a Mongolian guard, this coordinated message was important to gather as many available weapons as possible.

Other foods and food displays

Imperial dishes served on this occasion included nine-jointed lotus roots which symbolize peace, and watermelons cut in the shape of lotus petals which symbolize reunion.[8] Teacups were placed on stone tables in the garden, where the family would pour tea and chat, waiting for the moment when the full moon's reflection appeared in the center of their cups.[8] Owing to the timing of the plant's blossoms, cassia wine is the traditional choice for the "reunion wine" drunk on the occasion. Also, people will celebrate by eating cassia cakes and candy.[22][23][24]

Food offerings made to deities are placed on an altar set up in the courtyard, including apples, pears, peaches, grapes, pomegranates, melons, oranges, and pomelos.[25] One of the first decorations purchased for the celebration table is a clay statue of the Jade Rabbit. In Chinese folklore, the Jade Rabbit was an animal that lived on the moon and accompanied Chang'e. Offerings of soy beans and cockscomb flowers were made to the Jade Rabbit.[8]

Nowadays, in southern China, people will also eat some seasonal fruit that may differ in different district but carrying the same meaning of blessing.

In Vietnam, cakes and fruits are not only consumed, but elaborately prepared as food displays. For example, glutinous rice flour and rice paste are molded into familiar animals. Pomelo sections can be fashioned into unicorns, rabbits, or dogs.[5] Villagers of Xuân La, just north of Hanoi, produce tò he, figurines made from rice paste and colored with natural food dyes.[5] Into the early decades of the twentieth century of Vietnam, daughters of wealthy families would prepare elaborate centerpieces filled with treats for their younger siblings. Well-dressed visitors could visit to observe the daughter's handiwork as an indication of her capabilities as a wife in the future. Eventually the practice of arranging centerpieces became a tradition not just limited to wealthy families.[5]

Courtship and matchmaking

The Mid-Autumn moon has traditionally been a choice occasion to celebrate marriages. Girls would pray to moon deity Chang'e to help fulfill their romantic wishes.[6]

In some parts of China, dances are held for young men and women to find partners. For example, young women are encouraged to throw their handkerchiefs to the crowd, and the young man who catches and returns the handkerchief has a chance at romance.[9] In Daguang, in southwest Guizhou Province, young men and women of the Dong people would make an appointment at a certain place. The young women would arrive early to overhear remarks made about them by the young men. The young men would praise their lovers in front of their fellows, in which finally the listening women would walk out of the thicket. Pairs of lovers would go off to a quiet place to open their hearts to each other.[1]

Into the early decades of the twentieth century Vietnam, young men and women used the festival as a chance to meet future life companions. Groups would assemble in a courtyard and exchange verses of song while gazing at the moon. Those who performed poorly were sidelined until one young man and one young woman remained, after which they would win prizes as well as entertain matrimonial prospects.[5]

Games and activities

During the 1920s and 1930s, ethnographer Chao Wei-pang conducted research on traditional games among men, women and children on or around the Mid-Autumn day in the Guangdong Province. These games relate to flights of the soul, spirit possession, or fortunetelling.[8]

- One type of activity, "Ascent to Heaven" (Chinese: 上天堂 shàng tiāntáng) involves a young lady selected from a circle of women to "ascend" into the celestial realm. While being enveloped in the smoke of burning incense, she describes the beautiful sights and sounds she encounters.[8]

- Another activity, "Descent into the Garden" (Chinese: 落花园 luò huāyuán), played among younger girls, detailed each girl's visit to the heavenly gardens. According to legend, a flower tree represented her, and the number and color of the flowers indicated the sex and number of children she would have in her lifetime.[8]

- Men played a game called "Descent of the Eight Immortals" (jiangbaxian), where one of the Eight Immortals took possession of a player, who would then assume the role of a scholar or warrior.[8]

- Children would play a game called "Encircling the Toad" (guanxiamo), where the group would form a circle around a child chosen to be a Toad King and chanted a song that transformed the child into a toad. He would jump around like a toad until water was sprinkled on his head, in which he would then stop.[8]

Practices by region and cultures

Xiamen

A unique tradition is celebrated quite exclusively in the island city of Xiamen. On the festival, families and friends gather to play a gambling sort of game involving 6 dice. People take turns in rolling the dice in a ceramic bowl with the results determining what they win. The number 4 is mainly what determines how big the prize is.[26]

Hong Kong and Macau

In Hong Kong and Macau, the day after the Mid-Autumn Festival is a public holiday rather than the festival date itself (unless that date falls on a Sunday, then Monday is also a holiday), because many celebration events are held at night. There are a number of festive activities such as lighting lanterns, but mooncakes are the most important feature there. However, people don't usually buy mooncakes for themselves, but to give their relatives as presents. People start to exchange these presents well in advance of the festival. Hence, mooncakes are sold in elegant boxes for presentation purpose. Also, the price for these boxes are not considered cheap—a four-mooncake box of the lotus seeds paste with egg yolks variety, can generally cost US$40 or more.[27] However, as environmental protection has become a concern of the public in recent years, many mooncake manufacturers in Hong Kong have adopted practices to reduce packaging materials to practical limits.[28] The mooncake manufacturers also explore in the creation of new types of mooncakes, such as ice-cream mooncake and snow skin mooncake.

There are also other traditions related to the Mid-Autumn Festival in Hong Kong. Neighbourhoods across Hong Kong set impressive lantern exhibitions with traditional stage shows, game stalls, palm readings, and many other festive activities. The grandest celebrations take place in Victoria Park (Hong Kong).[29] One of the brightest rituals is the Fire Dragon Dance dating back to the 19th century and recognised as a part of China's intangible cultural heritage.[30][31] The 200 foot-long fire dragon requires more than 300 people to operate, taking turns. The leader of the fire dragon dance would pray for peace, good fortune through blessings in Hakka. After the ritual ceremony, fire-dragon was thrown into the sea with lanterns and paper cards, which means the dragon would return to sea and take the misfortunes away.[31]

Before 1941, There were also some celebration of Mid-Autumn Festival held in small villages in Hong Kong. Sha Po would celebrate Mid Autumn Festival in every 15th day of the 8th lunar month.[32] People called Mid Autumn Festival as Kwong Sin Festival, they hold Pok San Ngau Tsai at Datong Pond in Sha Po. Pok San Ngau Tsai was a celebration event of Kwong Sin Festival, people would gather around to watch it. During the event, someone would play the percussions, Some villagers would then acted as possessed and called themselves as "Maoshan Masters". They burnt themselves with incense sticks and fought with real blades and spears.

Ethnic minorities in China

- Korean minorities living in Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture have a custom of welcoming the moon, where they put up a large conical house frame made of dry pine branches and call it a "moon house". The moonlight would shine inside for gazers to appreciate.[1]

- The Bouyei people call the occasion "Worshiping Moon Festival", where after praying to ancestors and dining together, they bring rice cakes to the doorway to worship the Moon Grandmother.[1]

- The Tu people practice a ceremony called "Beating the Moon", where they place a basin of clear water in the courtyard to reflect an image of the moon, and then beat the water surface with branches.[1]

- The Maonan people tie a bamboo near the table, on which a grapefruit is hung, with three lit incense sticks on it. This is called "Shooting the Moon."[1]

Vietnam

The Mid-Autumn festival is named "Tết Trung Thu" in Vietnamese. It is also known as Children's Festival because of the event's emphasis on children.[2] In olden times, the Vietnamese believed that children, being innocent and pure, had the closest connection to the sacred and natural world. Being close to children was seen as a way to connect with animist spirits and deities.[11]

In its most ancient form, the evening commemorated the dragon who brought rain for the crops.[5] Celebrants would observe the moon to divine the future of the people and harvests. Eventually the celebration came to symbolize a reverence for fertility, with prayers given for bountiful harvests, increase in livestock, and human babies. Over time, the prayers for children evolved into a celebration of children.[5] Confucian scholars continued the tradition of gazing at the moon, but to sip wine and improvise poetry and song.[5] By the early twentieth century in Hanoi, the festival had begun to assume its identity as a children's festival.[5]

Aside from the story of Chang'e (Vietnamese: Hằng Nga), there are two other popular folktales associated with the festival. The first describes the legend of Cuội, whose wife accidentally urinated on a sacred banyan tree. The tree began to float towards the moon, and Cuội, trying to pull it back down to earth, floated to the moon with it, leaving him stranded there. Every year, during the Mid-Autumn Festival, children light lanterns and participate in a procession to show Cuội the way back to Earth.[33] The other tale involves a carp who wanted to become a dragon, and as a result, worked hard throughout the year until he was able to transform himself into a dragon.[2]

One important event before and during the festival are lion dances. Dances are performed by both non-professional children's groups and trained professional groups. Lion dance groups perform on the streets, going to houses asking for permission to perform for them. If the host consents, the "lion" will come in and start dancing as a blessing of luck and fortune for the home. In return, the host gives lucky money to show their gratitude.[citation needed]

Philippines

In the Philippines, the Chinese Filipino community celebrate the evening and exchange mooncakes with fellow friends, families and neighbors.[34] A game of chance, originating from the island city of Xiamen in China,[26] known as Pua Tiong Chiu which means "mid-autumn gambling" in Philippine Hokkien (see 中秋博饼), or simply mid-autumn dice game, is also played by both Filipino-Chinese and Filipinos alike.[35]

Taiwan

In Taiwan, the Mid-Autumn Festival is a public holiday. Outdoor barbecues have become a popular affair for friends and family to gather and enjoy each other's company.[36] As of 2016, Taipei City designated 15 riverside parks to accommodate outdoor barbecues for the public.[37]

Similar traditions in other parts of Asia

Similar traditions are found in other parts of Asia and also revolve around the full moon. These festivals tend to occur on the same day or around the Mid-Autumn Festival.

South Asia

India

Onam is an annual Harvest festival in the state of Kerala in India.It falls on the 22nd nakshatra Thiruvonam in the Malayalam calendar month of Chingam, which in Gregorian calendar overlaps with August–September. According to legends, the festival is celebrated to commemorate King Mahabali, whose spirit is said to visit Kerala at the time of Onam.

Onam is a major annual event for Malayali people in and outside Kerala. It is a harvest festival, one of three major annual Hindu celebrations along with Vishu and Thiruvathira, and it is observed with numerous festivities. Onam celebrations include Vallam Kali (boat races), Pulikali (tiger dances), Pookkalam (flower Rangoli), Onathappan (worship), Onam Kali, Tug of War, Thumbi Thullal (women's dance), Kummattikali (mask dance), Onathallu (martial arts), Onavillu (music), Kazhchakkula (plantain offerings), Onapottan (costumes), Atthachamayam (folk songs and dance), and other celebrations.

Onam is the official state festival of Kerala with public holidays that start four days from Uthradom (Onam eve). Major festivities take place across 30 venues in Thiruvananthapuram, capital of Kerala. It is also celebrated by Malayali diaspora around the world. Though a Hindu festival, non-Hindu communities of Kerala participate in Onam celebrations considering it as a cultural festival.

Sharad Purnima is a harvest festival celebrated on the full moon day of the Hindu lunar month of Ashvin (September–October), marking the end of the monsoon season.

Sri Lanka

In Sri Lanka, a full moon day is known as Poya and each full moon day is a public holiday. Shops and businesses are closed on these days as people prepare for the full moon.[38] Exteriors of buildings are adorned with lanterns and people often make food and go to the temple to listen to sermons.[39] The Binara Full Moon Poya Day and Vap Full Moon Poya Day occur around the time of the Mid-Autumn Festival and like other Buddhist Asian countries, the festivals celebrate the ascendance and culmination of the Buddha's visit to heaven and for the latter, the acknowledgement of the cultivation season known as "Maha".[40][41][42]

East Asia

Japan

The Japanese moon viewing festival, o-tsukimi, is also held at this time. People picnic and drink sake under the full moon to celebrate the harvest.

Korea

Chuseok (추석; 秋夕; [tɕʰu.sʌk̚]), literally "Autumn eve", once known as hangawi (한가위; [han.ɡa.ɥi]; from archaic Korean for "the great middle (of autumn)"), is a major harvest festival and a three-day holiday in North Korea and South Korea celebrated on the 15th day of the 8th month of the lunar calendar on the full moon. As a celebration of the good harvest, Koreans visit their ancestral hometowns and share a feast of Korean traditional food such as songpyeon (송편) and rice wines such as sindoju and dongdongju.

Southeast Asia

Many festivals revolving around a full moon are also celebrated in Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Sri Lanka. Like the Mid-Autumn Festival, these festivals have Buddhist origins and revolve around the full moon however unlike their East Asian counterparts they occur several times a year to correspond with each full moon as opposed to one day each year. The festivals that occur in the lunar months of Ashvini and Kṛttikā generally occur during the Mid-Autumn Festival.[43][44]

Cambodia

In Cambodia, it is more commonly called "Full Moon Festival" by locals (as Cambodia does not have an Autumn season). Cambodians organize “the traditional festival of prostrating the moon". In that early morning, people start preparing sacrifices to worship the moon, including fresh flowers, cassava soup, flat rice, and sugar cane juice. At night, people put the sacrifices into a tray, place on a big mat, and sit at ease waiting for the moon. When the moon rises up over the top of a branch, everyone whole-heartedly worships the moon, implores blessings. After the ritual of worshipping the moon, the old take flat rice to put into the mouth of children until they are entirely full in order to spray for perfection, and good things. Many Cambodians celebrate this festival as it is believed that exchanging moon cake during this time is thought to bring luck and prosperity. Among Cambodians, this holiday is associated with Khmer beliefs of 'Sampeah Preah Ke' translated to "Praying to the Moon" and the Buddhist legend of the rabbit.[45][46]

Laos

In Laos, many festivals are held on the day of the full moon. The most popular festival known as the That Luang Festival is associated with Buddhist legend and is held at Pha That Luang temple in Vientiane. The festival often lasts for three to seven days. A procession occurs and many people visit the temple.[47]

Myanmar

In Myanmar, numerous festivals are held on the day of the full moon however Thadingyut Festival is the most popular one and occurs in the month of Thadingyut. It also occurs around the time of the Mid-Autumn Festival, depending on the lunar calendar. It is one of the biggest festivals in Myanmar after the New Year festival, Thingyan. It is a Buddhist festival and many people go to the temple to pay respect to the monks and offer food.[48] It is also a time for thanksgiving and paying homage to Buddhist monks, teachers, parents and elders.[49]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Xing Li, Festivals of China's Ethnic Minorities (China Intercontinental Press, 2006, ISBN 7508509994).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Jonathan H.X. Lee and Kathleen M. Nadeau (eds.), Encyclopedia of Asian American Folklore and Folklife (ABC-CLIO, 2011, ISBN 0313350663).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Kin Wai Michael Siu, Lanterns of the mid-Autumn Festival: A Reflection of Hong Kong Cultural Change The Journal of Popular Culture 33(2) (1999): 67–86. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Fercility, The Origins and History of China’s Mid-Autumn Festival China Highlights, September 24, 2019. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 Van Huy Nguyen and Laurel Kendall (eds.), Vietnam: Journeys of Body, Mind, and Spirit (University of California Press, 2003, ISBN 9780520238725).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Christian Roy, Traditional Festivals: A Multicultural Encyclopedia (ABC-CLIO, 2004, ISBN 1576070891).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Lihui Yang, Deming An, and Jessica Anderson Turner, Handbook of Chinese Mythology (Oxford University Press, 2008, ISBN 0195332636).

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 Carol Stepanchuk and Charles Choy Wong, Mooncakes and Hungry Ghosts: Festivals of China (China Books & Periodicals, 1992, ISBN 0835124819).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Mid-Autumn Festival and its traditions ChinaDaily, August 31, 2011. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ↑ Joanne Ma, This Mid-Autumn Festival, learn all about the ancient Chinese tradition of writing riddles on lanterns - and solve some yourself Young Post, September 24, 2018. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Barbara Cohen, Mid-Autumn Children's Festival Things Asian, October 1, 1995. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- ↑ "Mid-Autumn Festival in Other Asian Countries", www.travelchinaguide.com.

- ↑ "A Chinese Symbol of Reunion: Moon Cakes – China culture", kaleidoscope.cultural-china.com. (written in en)

- ↑ "Back to Basics: Baked Traditional Moon Cakes", August 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Mooncakes: China's Evolving Tradition", The Atlantic.

- ↑ Customs around the Mid-Autumn Festival (September 7, 2016).

- ↑ 中秋节传统习俗:吃月饼.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 中秋食品. Academy of Chinese Studies. Retrieved December 16, 2012.

- ↑ Yan, Alice, "Chinese city’s record 2.4-metre-wide Mid-Autumn Festival mooncake cut down to size for hungry fans", September 4, 2016. Retrieved December 25, 2017.

- ↑ Wei, Liming (2011-08-25). Chinese festivals, Updated, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521186599.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedyang - ↑ Li Zhengping. Chinese Wine, p. 101. Cambridge University Press (Cambridge), 2011. Accessed November 8, 2013.

- ↑ Qiu Yaohong. Origins of Chinese Tea and Wine, p. 121. Asiapac Books (Singapore), 2004. Accessed November 7, 2013.

- ↑ Liu Junru. Chinese Food, p. 136. Cambridge Univ. Press (Cambridge), 2011. Accessed November 7, 2013.

- ↑ Tom, K.S. (1989). Echoes from old China: life, legends, and lore of the Middle Kingdom. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0824812850.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Xiamen rolls the dice, parties for Moon Festival.

- ↑ 10 must-order mooncakes for Mid-Autumn Festival 2017 (2017-08-09).

- ↑ Voluntary Agreement on Management of Mooncake Packaging. Environmental Protection Department of Hong Kong (March 18, 2013). Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- ↑ Mid-Autumn Festival. Hong Kong Tourism Board.

- ↑ Mid-Autumn Festival. rove.me.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Local Festivals: 8th Lunar Month. Retrieved 2019-03-05.

- ↑ https://www.hkmemory.hk/collections/oral_history/All_Items_OH/oha_104/highlight/index.html Hong Kong memory

- ↑ Wong, Bet Key. Tet Trung Thu. FamilyCulture.com. Archived from the original on June 23, 2012. Retrieved November 14, 2010.

- ↑ Jose Vidamor B. Yu, Inculturation of Filipino: Chinese Culture Mentality (Gregorian University Press, 2000, ISBN 8876528482).

- ↑ Ember, Carol R. (2004). Encyclopedia of diasporas : immigrant and refugee cultures around the world, [Online-Ausg.], Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-0306483219.

- ↑ Yeo, Joanna, "Traditional BBQ for Mid-Autumn Festival?", September 20, 2012. Retrieved November 10, 2012.

- ↑ "Mid-Autumn Festival: Officials list legal barbecue sites for festival", September 12, 2016. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- ↑ 冯明惠. How the world celebrates Mid-Autumn Festival. Chinadaily.com.cn.

- ↑ Mid-Autumn Festival Traditions. All China Women's Federation.

- ↑ Poya – Sri Lanka – Office Holidays.

- ↑ september calendar.

- ↑ Today is Vap Full Moon Poya Day.

- ↑ How the world celebrates Mid-Autumn Festival – Chinese News. chinesetimesschool.com.

- ↑ 上海百润投资控股集团股份有限公司.

- ↑ Asian Mid Autumn Festival. Blog's GoAsiaDayTrip (August 25, 2016).

- ↑ Moon Festival in Cambodia – An Unforgettable Experience.

- ↑ That Luang Festival – Event Carnival.

- ↑ Long, Douglas. Thadingyut: Festival of Lights.

- ↑ Myanmar Festivals 2016–2017.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Lee, Jonathan H.X., and Kathleen M. Nadeau (eds.). Encyclopedia of Asian American Folklore and Folklife. ABC-CLIO, 2011. ISBN 0313350663

- Li, Xing. Festivals of China's Ethnic Minorities. China Intercontinental Press, 2006. ISBN 7508509994

- Nguyen, Van Huy, and Laurel Kendall (eds.). Vietnam: Journeys of Body, Mind, and Spirit. University of California Press, 2003. ISBN 9780520238725

- Roy, Christian. Traditional Festivals: A Multicultural Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2004. ISBN 1576070891

- Stepanchuk, Carol, and Charles Choy Wong. Mooncakes and Hungry Ghosts: Festivals of China. China Books & Periodicals, 1992. ISBN 0835124819

- Yang, Lihui, Deming An, and Jessica Anderson Turner. Handbook of Chinese Mythology. Oxford University Press, 2008. ISBN 0195332636

- Yu, Jose Vidamor B. Inculturation of Filipino: Chinese Culture Mentality. Gregorian University Press, 2000. ISBN 8876528482

External links

All links retrieved

- San Francisco Chinatown Autumn Moon Festival

- Brief video about the history and traditions of Mid-Autumn Festival at YouTube

- More than just mooncakes: A guide to Mid-Autumn Festival

- Mid-Autumn Festival

- Mid-Autumn Festival: What is it and how is it celebrated?

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.