Michael Faraday

|

Michael Faraday | |

|---|---|

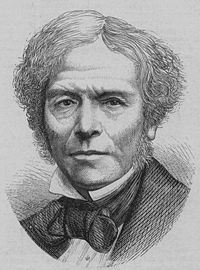

Michael Faraday from a photograph by John Watkins, British Library[1] | |

| Born |

September 22, 1791 |

| Died | August 25, 1867 |

| Residence | |

| Nationality | |

| Field | Physicist and Chemist |

| Institutions | Royal Institution |

| Academic advisor | Humphry Davy |

| Known for | Electromagnetic induction |

| Notable prizes | Royal Medal (1846) |

| Religious stance | Sandemanian |

| Note that Faraday did not have a tertiary education, however Humphry Davy is considered to be the equivalent of his doctoral advisor in terms of academic mentorship. | |

Michael Faraday, FRS (September 22, 1791 – August 25, 1867) was an English chemist and physicist (or natural philosopher, in the terminology of that time) who contributed significantly to the fields of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. He established that magnetism could affect rays of light and that there was an underlying relationship between the two phenomena.

Some historians of science refer to him as the best experimentalist in the history of science. It was largely due to his efforts that electricity became viable for use in technology. The SI unit of capacitance, the farad, is named after him, as is the Faraday constant, the charge on a mole of electrons (about 96,485 coulombs). Faraday's law of induction states that a magnetic field changing in time creates a proportional electromotive force.

He held the post of Fullerian Professor of Chemistry at the Royal Institution of Great Britain. Faraday was the first, and most famous, holder of this position to which he was appointed for life.

Career outline

Michael Faraday was born in Newington Butts, near present-day Elephant and Castle in South London, England. His family was extremely poor; his father, James Faraday, was a Yorkshire blacksmith who suffered ill-health throughout his life. After the most basic of school educations, Faraday had to educate himself. At fourteen he became apprenticed to a local bookbinder and book seller George Riebau and, during his seven-year apprenticeship, he read many books, including Isaac Watts' The Improvement of the Mind, the principles and suggestions contained therein he enthusiastically implemented. He developed an interest in science and specifically electricity. In particular, he was inspired by the book Conversations in Chemistry by Jane Marcet.

At the age of twenty, in 1812, at the end of his apprenticeship, Faraday attended lectures by the eminent English chemist and physicist Humphry Davy of the Royal Institution and Royal Society, and John Tatum, founder of the City Philosophical Society. Many tickets for these lectures were given to Faraday by William Dance (one of the founders of the Royal Philharmonic Society). Afterwards, Faraday sent Davy a three hundred page book based on notes taken during the lectures. Davy's reply was immediate, kind and favorable. When Davy damaged his eyesight in an accident with nitrogen trichloride, he decided to employ Faraday as a secretary. When John Payne, one of the Royal Institution's assistants, was sacked, the now Sir Humphry Davy was asked to find a replacement. He appointed Faraday as Chemical Assistant at the Royal Institution on 1 March 1813.

In the class-based English society of the time, Faraday was not considered a gentleman. When Davy went on a long tour to the continent in 1813-5, his valet did not wish to go. Faraday was going as Davy's scientific assistant, and was asked to act as Davy's valet until a replacement could be found in Paris. Davy failed to find a replacement, and Faraday was forced to fill the role of valet as well as assistant throughout the trip. Davy's wife, Jane Apreece, refused to treat Faraday as an equal (making him travel outside the coach, eat with the servants, etc.) and generally made Faraday so miserable that he contemplated returning to England alone and giving up science altogether. The trip did, however, give him access to the European scientific elite and a host of stimulating ideas.

His sponsor and mentor was John 'Mad Jack' Fuller, who created the Fullerian Professorship of Chemistry at the Royal Institution.

Faraday was a devout Christian and a member of the small Sandemanian denomination, an offshoot of the Church of Scotland. He later served two terms as an elder in the group's church.

Faraday married Sarah Barnard (1800-1879) on June 2, 1821, although they would never have children. They met through attending the Sandemanian church.

He was elected a member of the Royal Society in 1824, appointed director of the laboratory in 1825; and in 1833 he was appointed Fullerian professor of chemistry in the institution for life, without the obligation to deliver lectures.

Scientific achievements

Chemistry

Faraday's earliest chemical work was as an assistant to Davy. He made a special study of chlorine, and discovered two new chlorides of carbon. He also made the first rough experiments on the diffusion of gases, a phenomenon first pointed out by John Dalton, the physical importance of which was more fully brought to light by Thomas Graham and Joseph Loschmidt. He succeeded in liquefying several gases; he investigated the alloys of steel, and produced several new kinds of glass intended for optical purposes. A specimen of one of these heavy glasses afterwards became historically important as the substance in which Faraday detected the rotation of the plane of polarisation of light when the glass was placed in a magnetic field, and also as the substance which was first repelled by the poles of the magnet. He also endeavoured, with some success, to make the general methods of chemistry, as distinguished from its results, the subject of special study and of popular exposition.

He invented an early form of what was to become the Bunsen burner, which is used almost universally in science laboratories as a convenient source of heat.[4]

Faraday worked extensively in the field of chemistry, discovering chemical substances such as benzene (which he called bicarburet of hydrogen), inventing the system of oxidation numbers, and liquefying gases such as chlorine. He prepared the first clathrate hydrate. Faraday also discovered the laws of electrolysis and popularized terminology such as anode, cathode, electrode, and ion, terms largely created by William Whewell. For these accomplishments, many modern chemists regard Faraday as one of the finest experimental scientists in history.

Electricity

His greatest work was with electricity. The first experiment which he recorded was the construction of a voltaic pile with seven halfpence pieces, stacked together with seven disks of sheet zinc, and six pieces of paper moistened with salt water. With this pile he decomposed sulphate of magnesia (first letter to Abbott, July 12, 1812).

In 1821, soon after the Danish physicist and chemist, Hans Christian Ørsted discovered the phenomenon of electromagnetism, Davy and British scientist William Hyde Wollaston tried but failed to design an electric motor. Faraday, having discussed the problem with the two men, went on to build two devices to produce what he called electromagnetic rotation: a continuous circular motion from the circular magnetic force around a wire and a wire extending into a pool of mercury with a magnet placed inside would rotate around the magnet if supplied with current from a chemical battery. The latter device is known as a homopolar motor. These experiments and inventions form the foundation of modern electromagnetic technology. Unwisely, Faraday published his results without acknowledging his debt to Wollaston and Davy, and the resulting controversy caused Faraday to withdraw from electromagnetic research for several years.

At this stage, there is also evidence to suggest that Davy may have been trying to slow Faraday’s rise as a scientist (or natural philosopher as it was known then). In 1825, for instance, Davy set him onto optical glass experiments, which progressed for six years with no great results. It was not until Davy's death, in 1829, that Faraday stopped these fruitless tasks and moved on to endeavors that were more worthwhile. Two years later, in 1831, he began his great series of experiments in which he discovered electromagnetic induction, though the discovery may have been anticipated by the work of Francesco Zantedeschi. His breakthrough came when he wrapped two insulated coils of wire around a massive iron ring, bolted to a chair, and found that upon passing a current through one coil, a momentary current was induced in the other coil. The iron ring-coil apparatus is still on display at the Royal Institution. In subsequent experiments he found that if he moved a magnet through a loop of wire, an electric current flowed in the wire. The current also flowed if the loop was moved over a stationary magnet.

His demonstrations established that a changing magnetic field produces an electric field. This relation was mathematically modelled by Faraday's law, which subsequently went on to become one of the four Maxwell equations. These in turn have evolved into the generalization known today as field theory.

Faraday later used the principle to construct the electric dynamo, the ancestor of modern power generators.

In 1839 he completed a series of experiments aimed at investigating the fundamental nature of electricity. Faraday used "static," used batteries, and used "animal electricity" to produce electrostatic attraction, electrolysis, magnetism, etc. He concluded that, contrary to scientific opinion of the time, the divisions between the various "kinds" of electricity were illusory. Faraday instead proposed that only a single "electricity" exists, and the changing values of quantity and intensity (voltage and charge) would produce different groups of phenomena.

Near the end of his career Faraday proposed that electromagnetic forces extended into the empty space around the conductor. This idea was rejected by his fellow scientists, and Faraday did not live to see this idea eventually accepted. Faraday's concept of lines of flux emanating from charged bodies and magnets provided a way to visualize electric and magnetic fields. That mental model was crucial to the successful development of electromechanical devices which dominated engineering and industry for the remainder of the 19th century.

In 1845 he discovered the phenomenon that he named diamagnetism, and what is now called the Faraday effect: The plane of polarization of linearly polarized light propagated through a material medium can be rotated by the application of an external magnetic field aligned in the propagation direction. He wrote in his notebook, "I have at last succeeded in illuminating a magnetic curve or line of force and in magnetising a ray of light". This established that magnetic force and light were related.

In his work on static electricity, Faraday demonstrated that the charge only resided on the exterior of a charged conductor, and exterior charge had no influence on anything enclosed within a conductor. This is because the exterior charges redistribute such that the interior fields due to them cancel. This shielding effect is used in what is now known as a Faraday cage.

Despite his excellence as an experimentalist, his mathematical ability did not extend so far as trigonometry or any but the simplest algebra. However, his experimental work was consolidated by the able James Clerk Maxwell, who developed his equations which lie at the base of all modern theories of electromagnetic phenomena. Faraday, nevertheless, was able to convey his ideas in clear and simple language.

Later life

In 1848, as a result of representations by the Prince Consort, Michael Faraday was awarded a Grace and favour house in Hampton Court, Surrey free of all expenses or upkeep. This was the Master Mason's House, later called Faraday House, and now No.37 Hampton Court Road. In 1858 he retired to live there.[5]

During his lifetime, Faraday rejected a knighthood and twice refused to become President of the Royal Society.

He died at his house at Hampton Court on August 25, 1867. He has a memorial plaque in Westminster Abbey, near Isaac Newton's tomb, but he turned down burial there and is interred in the Sandemanian plot in Highgate Cemetery.

Miscellaneous

Faraday gave a successful series of lectures on the chemistry and physics of flames at the Royal Institution, entitled The Chemical History of a Candle. This was the origin of the Christmas lectures for young people, which are still given there every year and bear his name.

Faraday refused to participate in the production of chemical weapons for the Crimean War citing ethical reasons.

A statue of Faraday stands in Savoy Place, London, outside the Institution of Electrical Engineers.

A Hall at Loughborough University was named after Faraday in 1960. Near the entrance to its dining hall is a bronze casting, which depicts the symbol of an electrical transformer, and inside there hangs a portrait, both in his honour.

His picture was printed on British £20 banknotes from 1991 until 2001.[6]

In the video game Chromehounds there is a ThermoVision Device named the Faraday.

Publications

Published Works by Michael Faraday

- Chemical Manipulation, being Instructions to Students in Chemistry (1 vol., John Murray, 1st ed. 1827, 2nd 1830, 3rd 1842);

- Experimental Researches in Electricity, vols. i. and ii., Richard and John Edward Taylor, vols. i. and ii. (1844 and 1847); vol. iii. (1844); vol. iii. Richard Taylor and William Francis (1855);

- Experimental Researches in Chemistry and Physics, Taylor and Francis (1859);

- A Course of Six Lectures on the Chemical History of a Candle (edited by W. Crookes) (Griffin, Bohn & Co., 1861);

- On the Various Forces in Nature (edited by W. Crookes) (Chatto & Windus, 1873).

- A Course of 6 lectures on the various forces of matter and their relations to each other. edited by William Crookes(1861).

- His Diary edited by T. Martin was published in eight volumes (1932 - 36)

Biographies

- Tyndall, John, Faraday as a Discoverer, (Longmans, 1st ed. 1868, 2nd ed. 1870);

- Jones, Bence Dr. , secretary of the Royal Institution, The Life and Letters of Faraday in 2 vols. (Longmans, 1870);

- Kraus, Brian, Dr., My Summer Building a Faraday Cage, (1983).;

- Gladstone, J. H. , Ph.D., F.R.S., Michael Faraday, (Macmillan, 1872);

- Thompson, S. P., Michael Faraday; his Life and Work, (1898). (J. C. M.)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- "FARADAY." at LoveToKnow 1911 Britannica Online Encyclopedia.[4]

- Hamilton, James (2002). Faraday: The Life. Harper Collins, London. ISBN 0-00-716376-2 .

- Hamilton, James (2004). A Life of Discovery: Michael Faraday, Giant of the Scientific Revolution. Random House, New York. ISBN 1-4000-6016-8 .

- Thomas, John Meurig (1991). Michael Faraday and the Royal Institution: The Genius of Man and Place Hilger, Bristol. ISBN 0-7503-0145-7

- Thompson, Silvanus (1901, reprinted 2005) “Michael Faraday, His Life and Work”. Cassell and Company, London, 1901; reprint by Kessenger Publishing, Whitefish, MT. ISBN 1-4179-7036-7

Notes

- ↑ [1] Image in British Library

- ↑ [2] National Portrait gallery NPG 269

- ↑ [3]National Portrait Gallery, UK

- ↑ The Origin of the Bunsen Burner (pdf) William B. Jensen, Journal of Chemical Education • Vol. 82 No. 4 April 2005 - Accessed June 2006

- ↑ [http://www.twickenham-museum.org.uk/detail.asp?ContentID=197 Twickenham Museum on Faraday and Faraday House , Accessed June 2006

- ↑ Bank of England, Withdrawn Notes

Quotations

- "Nothing is too wonderful to be true."

- "Work. Finish. Publish." — his well-known advice to the young William Crookes

- "The important thing is to know how to take all things quietly."

- Regarding the hereafter, "Speculations? I have none. I am resting on certainties. I know whom I have believed and am persuaded that he is able to keep that which I have committed unto him against that day."

- "Next Sabbath day (the 22nd) I shall complete my 70th year. I can hardly think of myself so old."

- Above the doorways of the Pfahler Hall of Science at Ursinus College in Collegeville, Pennsylvania, there is a stone inscription of a quote attributed to Michael Faraday which reads "but still try, for who knows what is possible..."

External links and articles

Biographies

- Detailed biography of Faraday

- IEE biography of Michael Faraday

- Faraday as a Discoverer by John Tyndall, Project Gutenberg (downloads)

- The Christian Character of Michael Faraday

- Biography at The Royal Institution of Great Britain

- Michael Faraday on the 20 British Pound banknote.

- Short biography of Faraday

Others

- {{{2}}} at the Open Directory Project

- Works by Michael Faraday. Project Gutenberg (downloads)

- "Experimental Researches in Electricity" by Michael Faraday Original text with Biographical Introduction by Professor John Tyndall, 1914, Everyman edition.

- Video Podcast with Sir John Cadogan talking about Benzene since Faraday

Further reading

- Ames, Joseph Sweetman (Ed.), "The discovery of induced electric currents" Vol. 2. Memoirs, by Michael Faraday. New York, Cincinnati [etc.] American book company [c1900] LCCN 00005889

See also

- UK topics

- Faraday's Diary, ¶ 7718, 30 September 1845 and ¶ 7504, 13 September 1845

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Faraday, Michael |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | British Physicist and Chemist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 22, 1791 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Newington Butts, England |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 25, 1867 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Hampton Court, London, England |

af:Michael Faraday ar:مايكل فاراداي bs:Michael Faraday ca:Michael Faraday cs:Michael Faraday da:Michael Faraday de:Michael Faraday et:Michael Faraday el:Μάικλ Φαραντέι es:Michael Faraday eo:Michael Faraday eu:Michael Faraday fa:مایکل فارادی fr:Michael Faraday gd:Michael Faraday gl:Michael Faraday ko:마이클 패러데이 hr:Michael Faraday id:Michael Faraday ia:Michael Faraday it:Michael Faraday he:מייקל פאראדיי ku:Michael Faraday lt:Maiklas Faradėjus hu:Michael Faraday nl:Michael Faraday ja:マイケル・ファラデー no:Michael Faraday nds:Michael Faraday pl:Michael Faraday pt:Michael Faraday ro:Michael Faraday ru:Фарадей, Майкл simple:Michael Faraday sk:Michael Faraday sl:Michael Faraday sr:Мајкл Фарадеј fi:Michael Faraday sv:Michael Faraday ta:மைக்கேல் பரடே vi:Michael Faraday tr:Michael Faraday uk:Майкл Фарадей zh:麥可·法拉第