Difference between revisions of "Matilda of Flanders" - New World Encyclopedia

m (→Her life) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (41 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{Images OK}} | + | {{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{copyedited}} |

{{Infobox British Royalty|majesty|consort | {{Infobox British Royalty|majesty|consort | ||

| name =Matilda of Flanders | | name =Matilda of Flanders | ||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

| imgw =200 | | imgw =200 | ||

| title =[[List of English consorts|Queen consort]] of the English<br/>[[Duke of Normandy|Duchess consort of Normandy]] | | title =[[List of English consorts|Queen consort]] of the English<br/>[[Duke of Normandy|Duchess consort of Normandy]] | ||

| − | | reign =25 | + | | reign =December 25, 1066 – November 2, 1083 |

| spouse =[[William I of England|William I the Conqueror]] | | spouse =[[William I of England|William I the Conqueror]] | ||

| issue =[[Robert Curthose|Robert II Curthose]]<br />[[William II of England|William II Rufus]]<br />[[Adela of Normandy|Adela, Countess of Blois]]<br />[[Henry I of England|Henry I Beauclerc]] | | issue =[[Robert Curthose|Robert II Curthose]]<br />[[William II of England|William II Rufus]]<br />[[Adela of Normandy|Adela, Countess of Blois]]<br />[[Henry I of England|Henry I Beauclerc]] | ||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

| place of burial =[[Abbaye aux Dames]] [[Caen]], [[Normandy]] | | place of burial =[[Abbaye aux Dames]] [[Caen]], [[Normandy]] | ||

|}} | |}} | ||

| − | '''Matilda of Flanders''' (c. 1031 – 2 | + | '''Matilda of Flanders''' (c. 1031 – November 2, 1083) was [[Queen consort]] of [[England]] and the wife of [[William I of England|William I the Conqueror]]. She and William had 10 or 11 children, two of whom were kings of England: [[William II of England|William Rufus]] (1056–1100) and his successor [[Henry I of England|Henry Beauclerc]] (1068–1135). She twice acted as [[regent]] for William in Normandy while in England and was the first wife of an English king to receive her own [[coronation]]. |

| − | + | Matilda was daughter of count [[Baldwin V, Count of Flanders|Baldwin V of Flanders]] and [[Adela of France, Countess of Flanders|Adèle]] (1000-1078/9), the daughter of [[Robert II of France]]. After a notoriously stormy courtship, she and William were thought to have been a peaceful, loving marriage, for the most part. However, their relationship was strained when her eldest son, Robert, opposed his father after a series family squabbles turned into war and William discovered that Matilda had been sending her son money. However, she was able to reconcile father and son, and the couple remained at peace until her death. All sovereigns of England and the United Kingdom since William I are directly descended from her. | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | For many years Matilda was mistakenly thought to have been responsible for the creation of the famous [[Bayeux Tapestry]]. | ||

| − | + | ==Biography== | |

| + | ===Early years=== | ||

| + | Matilda was descended on her father's side from King [[Alfred the Great]] of England. At 4'2" (127 cm) tall, she would become, according to the ''[[Guinness Book of Records]],'' [[England]]'s smallest queen. | ||

| − | + | Legend has it that when the emissary of [[William I of England|William, Duke of Normandy]] (later [[king of England]] as [[William the Conqueror]]), came to ask for her hand in marriage, Matilda considered herself far too high-born to consider marrying him, since he was considered a [[bastard]]. (William was the surviving son of the two children of Robert I, duke of Normandy, 1027–35, and his concubine Herleva.) The story goes that when her response was reported to him, William rode from Normandy to [[Bruges]], found Matilda on her way to church, dragged her off her horse by her long braids, threw her down in the street in front of her flabbergasted attendants, and then rode off. Another version relates that William rode to Matilda's father's house in Lille, threw her to the ground in her room (again by the braids), and either hit her or violently shook her before leaving. Naturally her father, Baldwin, took offense at this. However, before they drew swords, Matilda, apparently impressed by his show of passion, settled the matter by deciding to marry William.<ref>Paul Hilliam (2005), 20.</ref> Even a papal ban by [[Pope Leo IX]] (on the grounds of [[consanguinity]]) did not dissuade her. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | William married Matilda in 1053 in the Cathedral of Notré Dame at Eu, Normandy (Seine-Maritime). William was about 24 years old and Matilda was 22. In repentance for what was considered by the [[pope]] a [[consanguinity|consanguine marriage]] (they were distant cousins), William and Matilda built and donated matching abbeys to the church. | |

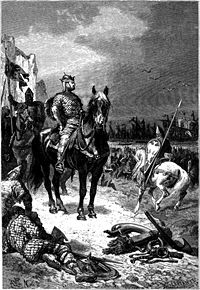

| − | William | + | [[Image:KingWilliam.jpg|thumb|200px|left|William the Conqueror entering England in 1066, by Alphonse Marie de Neuville, 1883]] |

| + | There were rumors that Matilda had previously been in love with the English ambassador to [[Flanders]], a Saxon named Brihtric, who declined her advances, after which she chose to marry William. Whatever the truth of the matter, years later when she was acting as [[Regent]] for William in England, she requested and received permission to use her authority to confiscate Brihtric's lands and threw him into prison, where he died. | ||

| − | + | When William was preparing to invade and conquer on the coast of England, Matilda had secretly outfitted a ship, the ''Mora'', out of her own money as a royal pledge of love and constancy during his absence. It was superbly outfitted with beautifully carved, painted and gilded fittings with a golden figure of their youngest son, William on the bow. This was said to be such a surprise to William and his men that it inspired their efforts for war and eventual victory. | |

| − | |||

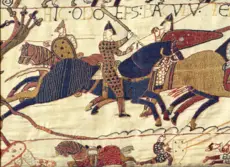

| − | + | [[Image:Odo bayeux tapestry.png|thumb|230px|Bishop Odo, likely originator of the [[Bayeux Tapestry]], seen spurring his troops forward.]] | |

| + | For many years it was thought that she had some involvement in the creation of the [[Bayeux Tapestry]] (commonly called ''La Tapisserie de la Reine Mathilde'' in French), but historians no longer believe that; it seems to have been commissioned by William's half-brother [[Odo of Bayeux|Odo, Bishop of Bayeux]], and made by English artists in [[Kent]] to coincide with the building of the Bayeux Cathedral. | ||

| − | Matilda bore William | + | Matilda bore William at least ten children, and he was believed to have been faithful to her, although there was rumor of one indiscretion in England to which Matilda reacted strongly. They experienced a good relationship at least up until the time their son Robert rebelled against his father. |

| − | + | ===Regent of Normandy=== | |

| + | When William invaded England, he left Matilda as regent with his young son Robert. Matilda appears to have ruled [[Normandy]] with great ability and success during the absence of her husband. Even though the government was weakened by the wealthy and the powerful having gone to support his cause in England, the duchy, under Matilda's regency, experienced neither rebellion or war. She continued to develop the arts and learning, and the culture of Normandy thus became more civilized and refined. | ||

| + | Soon William sent for Matilda to share in his triumph in England. She was accompanied by [[Gui, Bishop of Amiens]], and numerous distinguished nobles. They reached England in the spring of 1068. The king was happy to have her join him, and preparations were made for her [[coronation]]. Never before had a queen been crowned alongside a king in England. After her coronation she was always addressed as "Queen Regina." This made her some enemies, as previously queens were addressed by the Saxons only as the kings' ladies or consorts. | ||

| + | [[Image:Heinrich der Löwe und Mathilde von England.jpg|thumb|250px|Henry the Lion and Matilda of England, 1188.]] | ||

| + | Their youngest son, Henry Beauclerc was born in Selby, in Yorkshire. However, there was difficulties in Normandy and the nobles requested William to send Matilda back. Matilda and their eldest son, Robert, were thus again appointed as regents of [[Normandy]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | During this time the king of France, in alliance with the duke of [[Brittany]], attacked William's continental possessions and encouraged the province of Maine to revolt. Matilda, realizing the danger to Normandy, sent to her husband for help. William was at war with the king of [[Scotland]], but sent the son of Fitz-Osborn, his great supporter, to help the queen. He then made a hasty peace with the Scottish king and traveled to Normandy with a large army. He crushed the rebellion and forced France to sue for peace, bringing stability to Normandy again. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Struggle between father and son=== | ||

| + | The problem with Robert began when his father returned to Normandy, as William took lands belonging to Robert's deceased fiancé, leaving Robert landless and subject to his father's control. Added to this, one day when two of Robert's brothers poured filthy water on him from a balcony above to humiliate him, William chose not to punish them for the prank. In a more serious vein, Robert's brother William Rufus wanted to replace Robert as inheritor to his father. Eventually, the situation evolved exponentially into a new Norman rebellion. It ended only when [[Philip of France|King Philip]] added his military support to William's forces, thus allowing him to confront Robert in battle at Flanders. | ||

| + | |||

| + | During the battle in 1079, Robert unhorsed a man in battle and wounded him. He stopped his attack only when he recognized his father's voice. Realizing how nearly he had come to killing his father, he knelt in repentance to his father and then helped him back on his horse. Humiliated, William cursed his son, then halted the siege and returned to Rouen, after which William revoked Robert's inheritance. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Robert de Normandie at the Siege of Antioch 1097-1098.JPG|thumb|170px|left|Eldest son, Robert Curthose, at the [[Siege of Antioch]] (1097-1098) while on crusade.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | William later discovered Matilda's emissary carrying money to Robert. When he confronted her, she cried and answered that her mother's love could not allow her to abandon her needy son. At Easter 1080, father and son were reunited by the efforts of Matilda, and a truce followed. However, they again quarreled and she fell ill from worry until she died in 1083. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Matilda had been duchess of Normandy for 31 years and queen of England for 17. Her dying prayer was for her favorite son, Robert, who was in England when she passed. After her death at the age of 51, William became more tyrannical, and people blamed it at least in part on his having lost her love and good counsel. | ||

| − | + | Contrary to the belief that she was buried at St. Stephen's, also called l'[[Abbaye-aux-Hommes]] in [[Caen]], [[Normandy]], where William was eventually buried, she is entombed at l'[[Abbaye aux Dames]], which is the Sainte-Trinité church, also in Caen. An eleventh century slab, a sleek black stone decorated with her epitaph, marks her grave at the rear of the church. It is of special note since the grave marker for William was replaced as recently as the beginning of the nineteenth century. Years later, their graves were opened and their bones measured, proving their physical statures. During the [[French Revolution]] both of their graves were robbed and their remains spread about, but the monks were able to retrieve the bones carefully back into their caskets. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Children== | ==Children== | ||

| − | |||

Some doubt exists over how many daughters there were. This list includes some entries which are obscure. | Some doubt exists over how many daughters there were. This list includes some entries which are obscure. | ||

| − | * [[Robert Curthose]] | + | [[Image:Henry I of England - Illustration from Cassell's History of England - Century Edition - published circa 1902.jpg|thumb|right|130px|[[Henry I of England|Henry I]]]] |

| − | * Adeliza (or Alice) | + | * [[Robert Curthose]], c. 1054–1134, Duke of Normandy, married [[Sybil of Conversano]], daughter of Geoffrey of Conversano |

| − | * [[Cecilia of Normandy|Cecilia]] | + | * Adeliza (or Alice), c. 1055–?, reportedly betrothed to [[Harold II of England]]. Her existence is in some doubt. |

| − | * [[William II of England|William Rufus]] | + | * [[Cecilia of Normandy|Cecilia]]/or Cecily, c. 1056–1126, Abbess of Holy Trinity, Caen |

| − | * [[Richard, Duke of Bernay]] | + | * [[William II of England|William Rufus]], 1056–1100, King of England |

| − | * Alison (or Ali) | + | * [[Richard, Duke of Bernay]], 1057–c. 1081, killed by a stag in [[New Forest]] |

| − | * [[Adela of Blois|Adela]] | + | * Alison (or Ali), 1056-c. 1090, was once announced the most beautiful lady, yet died unmarried |

| − | * [[Agatha of Normandy|Agatha]] | + | * [[Adela of Blois|Adela]], c. 1062–1138, married [[Stephen, Count of Blois]] |

| − | + | * [[Agatha of Normandy|Agatha]], c. 1064–c. 1080, betrothed to Harold of [[Wessex]] and later to [[Alfonso VI of Castile]] | |

| − | * [[Constance of Normandy|Constance]] | + | * [[Constance of Normandy|Constance]], c. 1066–1090, married [[Alan IV, Duke of Brittany|Alan IV Fergent]], [[Duke of Brittany]]; poisoned, possibly by her own servants |

| − | * Matilda | + | * Matilda, very obscure, her existence is in some doubt |

| − | * [[Henry I of England|Henry Beauclerc]] | + | * [[Henry I of England|Henry Beauclerc]], 1068-1135, became Henry I of England after his brother William died. |

| − | [[Gundred]] | + | [[Gundred]], c. 1063–1085, wife of [[William de Warenne, 1st Earl of Surrey|William de Warenne]], c. 1055–1088, was formerly thought of as being yet another of Matilda's daughters. However, her lineal connection to either William I of Matilda is now considered without foundation. |

==Legacy== | ==Legacy== | ||

| − | [[Image:Matilda of Flanders Jardin du Luxembourg.jpg|thumb| | + | [[Image:Matilda of Flanders Jardin du Luxembourg.jpg|thumb|120px|Queen Matilda (1850), Luxembourg Garden, Paris]] |

| − | Matilda | + | Matilda was the first crowned queen of England, as well as capably governing Normandy as regent on two occasions during William's absence. For many years Matilda was credited with the creation of the [[Bayeux Tapestry]], although later scholarship makes this extremely unlikely. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | For many years Matilda | ||

| − | + | In addition to her successful regency in Normandy while her husband was in England, Matilda's legacy is best seen through her royal lineage and descendants. She was a seventh generation direct descendant of [[Alfred the Great]], and her marriage to William strengthened his claim to the throne. All later sovereigns of England and the [[United Kingdom]] are directly descended continuously from her, including Queen [[Elizabeth II]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| − | + | <references/> | |

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * Cantor, Norman F. ''The Civilization of the Middle Ages'' | + | * Cantor, Norman F. ''The Civilization of the Middle Ages.'' Harper Perennial, 1994. ISBN 0060925531. |

| − | * Douglas, David C. ''William the Conqueror; the Norman | + | * Douglas, David C. ''William the Conqueror; the Norman Impact upon England''. Berkeley, CA: University of California, 1964. ISBN 0520003500. |

| − | * Fettu, Annie. ''Queen Matilda: Princess of Flanders, Duchess of Normandy, Queen of England, circa 1032 - 1083'' | + | * Fettu, Annie. ''Queen Matilda: Princess of Flanders, Duchess of Normandy, Queen of England, circa 1032-1083.'' Cully: Orep Editions, 2005. ISBN 9782912925817. |

| − | * Hilliam, Paul. ''William the Conqueror: First Norman King of England'' | + | * Hilliam, Paul. ''William the Conqueror: First Norman King of England.'' Rosen Publishing Group, 2005. ISBN 1404201661. |

| − | * Lewis, Hilda Winifred. ''Wife to the | + | * Lewis, Hilda Winifred. ''Wife to the Bastard.'' New York, D. McKay Co., 1966. {{OCLC|1378149}}. |

| − | * Strickland, Agnes. ''Lives of the | + | * Strickland, Agnes. ''Lives of the Queens of England 1. Matilda of Flanders. Matilda of Scotland. Adelicia of Louvaine. Matilda of Boulogne. Eleonora of Aquitaine. 1840.'' London: Colburn, 1840. {{OCLC|165803070}}. |

| − | * | + | * —. ''Lives of the Queens of England from the Norman Conquest: With Anecdotes of Their Courts.'' Philadelphia: Lea & Blanchard, 1841. {{OCLC|8830518}}. |

| + | |||

| + | ==External links== | ||

| + | All links retrieved November 7, 2022. | ||

| + | * [http://www.monsalvat.globalfolio.net/eng/dominator/matilda_of_flanders/lancelott/index.php "Matilda of Flanders, Queen of William the First, usually styled William the Conqueror," by Francis Lancelott Esq. (1858)] | ||

{{English consort}} | {{English consort}} | ||

Latest revision as of 16:52, 7 November 2022

| Matilda of Flanders | |

|---|---|

| Queen consort of the English Duchess consort of Normandy | |

| |

| Consort | December 25, 1066 – November 2, 1083 |

| Consort to | William I the Conqueror |

| Issue | |

| Robert II Curthose William II Rufus Adela, Countess of Blois Henry I Beauclerc | |

| Royal House | House of Normandy |

| Father | Baldwin V, Count of Flanders |

| Mother | Adela Capet |

| Born | c. 1031 |

| Died | 2 November 1083 (aged c. 52) |

| Buried | Abbaye aux Dames Caen, Normandy |

Matilda of Flanders (c. 1031 – November 2, 1083) was Queen consort of England and the wife of William I the Conqueror. She and William had 10 or 11 children, two of whom were kings of England: William Rufus (1056–1100) and his successor Henry Beauclerc (1068–1135). She twice acted as regent for William in Normandy while in England and was the first wife of an English king to receive her own coronation.

Matilda was daughter of count Baldwin V of Flanders and Adèle (1000-1078/9), the daughter of Robert II of France. After a notoriously stormy courtship, she and William were thought to have been a peaceful, loving marriage, for the most part. However, their relationship was strained when her eldest son, Robert, opposed his father after a series family squabbles turned into war and William discovered that Matilda had been sending her son money. However, she was able to reconcile father and son, and the couple remained at peace until her death. All sovereigns of England and the United Kingdom since William I are directly descended from her.

For many years Matilda was mistakenly thought to have been responsible for the creation of the famous Bayeux Tapestry.

Biography

Early years

Matilda was descended on her father's side from King Alfred the Great of England. At 4'2" (127 cm) tall, she would become, according to the Guinness Book of Records, England's smallest queen.

Legend has it that when the emissary of William, Duke of Normandy (later king of England as William the Conqueror), came to ask for her hand in marriage, Matilda considered herself far too high-born to consider marrying him, since he was considered a bastard. (William was the surviving son of the two children of Robert I, duke of Normandy, 1027–35, and his concubine Herleva.) The story goes that when her response was reported to him, William rode from Normandy to Bruges, found Matilda on her way to church, dragged her off her horse by her long braids, threw her down in the street in front of her flabbergasted attendants, and then rode off. Another version relates that William rode to Matilda's father's house in Lille, threw her to the ground in her room (again by the braids), and either hit her or violently shook her before leaving. Naturally her father, Baldwin, took offense at this. However, before they drew swords, Matilda, apparently impressed by his show of passion, settled the matter by deciding to marry William.[1] Even a papal ban by Pope Leo IX (on the grounds of consanguinity) did not dissuade her.

William married Matilda in 1053 in the Cathedral of Notré Dame at Eu, Normandy (Seine-Maritime). William was about 24 years old and Matilda was 22. In repentance for what was considered by the pope a consanguine marriage (they were distant cousins), William and Matilda built and donated matching abbeys to the church.

There were rumors that Matilda had previously been in love with the English ambassador to Flanders, a Saxon named Brihtric, who declined her advances, after which she chose to marry William. Whatever the truth of the matter, years later when she was acting as Regent for William in England, she requested and received permission to use her authority to confiscate Brihtric's lands and threw him into prison, where he died.

When William was preparing to invade and conquer on the coast of England, Matilda had secretly outfitted a ship, the Mora, out of her own money as a royal pledge of love and constancy during his absence. It was superbly outfitted with beautifully carved, painted and gilded fittings with a golden figure of their youngest son, William on the bow. This was said to be such a surprise to William and his men that it inspired their efforts for war and eventual victory.

For many years it was thought that she had some involvement in the creation of the Bayeux Tapestry (commonly called La Tapisserie de la Reine Mathilde in French), but historians no longer believe that; it seems to have been commissioned by William's half-brother Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, and made by English artists in Kent to coincide with the building of the Bayeux Cathedral.

Matilda bore William at least ten children, and he was believed to have been faithful to her, although there was rumor of one indiscretion in England to which Matilda reacted strongly. They experienced a good relationship at least up until the time their son Robert rebelled against his father.

Regent of Normandy

When William invaded England, he left Matilda as regent with his young son Robert. Matilda appears to have ruled Normandy with great ability and success during the absence of her husband. Even though the government was weakened by the wealthy and the powerful having gone to support his cause in England, the duchy, under Matilda's regency, experienced neither rebellion or war. She continued to develop the arts and learning, and the culture of Normandy thus became more civilized and refined.

Soon William sent for Matilda to share in his triumph in England. She was accompanied by Gui, Bishop of Amiens, and numerous distinguished nobles. They reached England in the spring of 1068. The king was happy to have her join him, and preparations were made for her coronation. Never before had a queen been crowned alongside a king in England. After her coronation she was always addressed as "Queen Regina." This made her some enemies, as previously queens were addressed by the Saxons only as the kings' ladies or consorts.

Their youngest son, Henry Beauclerc was born in Selby, in Yorkshire. However, there was difficulties in Normandy and the nobles requested William to send Matilda back. Matilda and their eldest son, Robert, were thus again appointed as regents of Normandy.

During this time the king of France, in alliance with the duke of Brittany, attacked William's continental possessions and encouraged the province of Maine to revolt. Matilda, realizing the danger to Normandy, sent to her husband for help. William was at war with the king of Scotland, but sent the son of Fitz-Osborn, his great supporter, to help the queen. He then made a hasty peace with the Scottish king and traveled to Normandy with a large army. He crushed the rebellion and forced France to sue for peace, bringing stability to Normandy again.

Struggle between father and son

The problem with Robert began when his father returned to Normandy, as William took lands belonging to Robert's deceased fiancé, leaving Robert landless and subject to his father's control. Added to this, one day when two of Robert's brothers poured filthy water on him from a balcony above to humiliate him, William chose not to punish them for the prank. In a more serious vein, Robert's brother William Rufus wanted to replace Robert as inheritor to his father. Eventually, the situation evolved exponentially into a new Norman rebellion. It ended only when King Philip added his military support to William's forces, thus allowing him to confront Robert in battle at Flanders.

During the battle in 1079, Robert unhorsed a man in battle and wounded him. He stopped his attack only when he recognized his father's voice. Realizing how nearly he had come to killing his father, he knelt in repentance to his father and then helped him back on his horse. Humiliated, William cursed his son, then halted the siege and returned to Rouen, after which William revoked Robert's inheritance.

William later discovered Matilda's emissary carrying money to Robert. When he confronted her, she cried and answered that her mother's love could not allow her to abandon her needy son. At Easter 1080, father and son were reunited by the efforts of Matilda, and a truce followed. However, they again quarreled and she fell ill from worry until she died in 1083.

Matilda had been duchess of Normandy for 31 years and queen of England for 17. Her dying prayer was for her favorite son, Robert, who was in England when she passed. After her death at the age of 51, William became more tyrannical, and people blamed it at least in part on his having lost her love and good counsel.

Contrary to the belief that she was buried at St. Stephen's, also called l'Abbaye-aux-Hommes in Caen, Normandy, where William was eventually buried, she is entombed at l'Abbaye aux Dames, which is the Sainte-Trinité church, also in Caen. An eleventh century slab, a sleek black stone decorated with her epitaph, marks her grave at the rear of the church. It is of special note since the grave marker for William was replaced as recently as the beginning of the nineteenth century. Years later, their graves were opened and their bones measured, proving their physical statures. During the French Revolution both of their graves were robbed and their remains spread about, but the monks were able to retrieve the bones carefully back into their caskets.

Children

Some doubt exists over how many daughters there were. This list includes some entries which are obscure.

- Robert Curthose, c. 1054–1134, Duke of Normandy, married Sybil of Conversano, daughter of Geoffrey of Conversano

- Adeliza (or Alice), c. 1055–?, reportedly betrothed to Harold II of England. Her existence is in some doubt.

- Cecilia/or Cecily, c. 1056–1126, Abbess of Holy Trinity, Caen

- William Rufus, 1056–1100, King of England

- Richard, Duke of Bernay, 1057–c. 1081, killed by a stag in New Forest

- Alison (or Ali), 1056-c. 1090, was once announced the most beautiful lady, yet died unmarried

- Adela, c. 1062–1138, married Stephen, Count of Blois

- Agatha, c. 1064–c. 1080, betrothed to Harold of Wessex and later to Alfonso VI of Castile

- Constance, c. 1066–1090, married Alan IV Fergent, Duke of Brittany; poisoned, possibly by her own servants

- Matilda, very obscure, her existence is in some doubt

- Henry Beauclerc, 1068-1135, became Henry I of England after his brother William died.

Gundred, c. 1063–1085, wife of William de Warenne, c. 1055–1088, was formerly thought of as being yet another of Matilda's daughters. However, her lineal connection to either William I of Matilda is now considered without foundation.

Legacy

Matilda was the first crowned queen of England, as well as capably governing Normandy as regent on two occasions during William's absence. For many years Matilda was credited with the creation of the Bayeux Tapestry, although later scholarship makes this extremely unlikely.

In addition to her successful regency in Normandy while her husband was in England, Matilda's legacy is best seen through her royal lineage and descendants. She was a seventh generation direct descendant of Alfred the Great, and her marriage to William strengthened his claim to the throne. All later sovereigns of England and the United Kingdom are directly descended continuously from her, including Queen Elizabeth II.

Notes

- ↑ Paul Hilliam (2005), 20.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cantor, Norman F. The Civilization of the Middle Ages. Harper Perennial, 1994. ISBN 0060925531.

- Douglas, David C. William the Conqueror; the Norman Impact upon England. Berkeley, CA: University of California, 1964. ISBN 0520003500.

- Fettu, Annie. Queen Matilda: Princess of Flanders, Duchess of Normandy, Queen of England, circa 1032-1083. Cully: Orep Editions, 2005. ISBN 9782912925817.

- Hilliam, Paul. William the Conqueror: First Norman King of England. Rosen Publishing Group, 2005. ISBN 1404201661.

- Lewis, Hilda Winifred. Wife to the Bastard. New York, D. McKay Co., 1966. OCLC 1378149.

- Strickland, Agnes. Lives of the Queens of England 1. Matilda of Flanders. Matilda of Scotland. Adelicia of Louvaine. Matilda of Boulogne. Eleonora of Aquitaine. 1840. London: Colburn, 1840. OCLC 165803070.

- —. Lives of the Queens of England from the Norman Conquest: With Anecdotes of Their Courts. Philadelphia: Lea & Blanchard, 1841. OCLC 8830518.

External links

All links retrieved November 7, 2022.

George, Duke of Cumberland (1702-1707) · Mary of Modena (1685-1688) · Catherine of Braganza (1662-1685) · Henrietta Maria of France (1625-1649) · Anne of Denmark (1603-1619) · Philip II of Spain (1554-1558) · Lord Guildford Dudley (1553) · Catherine Parr (1543-1547) · Catherine Howard (1540-1542) · Anne of Cleves (1540) · Jane Seymour (1536-1537) · Anne Boleyn (1533-1536) · Catherine of Aragon (1509-1533) · Elizabeth of York (1486-1503) · Anne Neville (1483-1485) · Elizabeth Woodville (1464-1483) · Margaret of Anjou (1445-1471) · Catherine of Valois (1420-1422) · Joanna of Navarre (1403-1413) · Isabella of Valois (1396-1399) · Anne of Bohemia (1383-1394) · Philippa of Hainault (1328-1369) · Isabella of France (1308-1327) · Marguerite of France (1299-1307) · Eleanor of Castile (1272-1290) · Eleanor of Provence (1236-1272) · Isabella of Angoulême (1200-1216) · Berengaria of Navarre (1191-1199) · Eleanor of Aquitaine (1154-1189) · Matilda of Boulogne (1135-1152) · Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou (1141) · Adeliza of Louvain (1121-1135) · Matilda of Scotland (1100-1118) · Matilda of Flanders (1066-1083)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.