Lewis and Clark Expedition

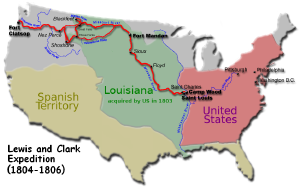

The Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804–1806) was the first United States transcontinental expedition and second overland journey to the Pacific coast, following the 1793 expedition by the Scotman Alexander Mackenzie, who reached the Pacific from Montreal. Commissioned by President Thomas Jeffersonfollowing the acquisition of vast western territories from France known as the Louisiana Purchase, the Corps of Discovery was led by Captain Meriwether Lewis, a frontiersman and personal secretary of Jefferson, and Second Lieutenant William Clark of the United States Army. The expedition sought to provide details about the newly acquired lands, specifically if the Mississippi-Missouri river system shared proximate sources with the Columbia River in the Pacific Northwest. During the two-year overland journey, the explorers discovered some 300 new species, encountered 50 unknown Indian tribes, and confirmed that the Rocky Mountain chain extended thousands of miles north from Mexico.

Traveling through remote and hostile Indian lands in a 4,000-mile wilderness journey, the expedition lost only one man, to appendicitis. The expedition set up diplomatic relations with the Indians with the help of the Shoshone Indian woman Sacajawea, who joined the expedition with her French husband and infant child. The explorers dramatically advanced knowledge of the interior of the continent, discovering and mapping navigable rivers, mountains, and other varied landscapes.

The Corps of Discovery charted an initial pathway for the new nation to spread westward, spawning a pattern of pioneer settlement that would become one of the defining attributes of the United States.The initial expedition and the publication of the explorers' journals would prompt families to go west in search of greater freedom and economic opportunity, transforming virgin forests and grasslands into farmlands, towns, and cities. No longer bound to the Atlantic seaboard, the nation would be transformed as new states fashioned from the virgin territories brought resources and productivity that would raise the country to preeminence by the beginning of the twentieth century.

Nomadic Native Americans were unable to resist the mass migration into their traditional hunting grounds and were eventually absorbed or placed on reservations.

Antecedents

U.S. President Thomas Jefferson had long considered an expedition to explore the North American continent. When he was Minister to France following the American Revolutionary War, from 1785-1789, he had heard numerous plans to explore the Pacific Northwest. In 1785, Jefferson learned that King Louis XVI of France planned to send a mission there, reportedly as a scientific expedition. Jefferson found that doubtful, and evidence provided by the former commander of the fledgling United States Navy and later admiral of the Russian Navy, John Paul Jones, confirmed these doubts. In either event, the mission was destroyed by bad weather after leaving Botany Bay in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia in 1788.

In 1803, then President Jefferson negotiated the acquisition of 828,000 square miles of western territory from France. The Louisiana Purchase, at the total cost of approximately $24 million, roughly doubled the size of the United States and in the view of Napoleon Bonaparte "affirm[ed] forever the power of the United States[;] I have given England a maritime rival who sooner or later will humble her pride." A few weeks after the purchase, Jefferson, an advocate of western expansion, had the Congress appropriate twenty five hundred dollars, "to send intelligent officers with ten or twelve men, to explore even to the Western ocean". They were to study the Indian tribes, botany, geology, Western terrain, and wildlife in the region, as well as evaluate the potential interference of British and French Canadian hunters and trappers who were already well established in the area. The expedition was not the first to cross North America, but was roughly a decade after the expedition of Alexander MacKenzie, the first European to cross north of Mexico to the Pacific Ocean, in 1793.

In a message to Congress, Jefferson wrote, "The river Missouri, and Indians inhabiting it, are not as well known as rendered desirable by their connection with the Mississippi, and consequently with us. . . . An intelligent officer, with ten or twelve chosen men . . . might explore the whole line, even to the Western Ocean."[1]

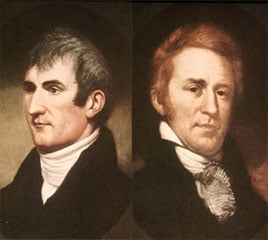

Jefferson selected Captain Meriwether Lewis to lead the expedition, afterward known as the Corps of Discovery; Lewis selected William Clark as his partner. Because of bureaucratic delays in the United States Army, Clark officially only held the rank of Second Lieutenant at the time, but Lewis concealed this from the men and shared the leadership of the expedition, always referring to Clark as "Captain."

In a letter dated June 20, 1803, Jefferson wrote to Lewis, "The object of your mission is to explore the Missouri river, and such principal stream of it as by its course and communication with the waters of the Pacific ocean whether the Columbia, Oregon, Colorado. or any other river may offer the most direct and practicable water communication across this continent for the purposes of commerce.[2]

Journey

The group, initially consisting of thirty three members, departed from Camp Dubois, near present day Hartford, Illinois, and began their historic journey on May 14, 1804. They soon met with Lewis in Saint Charles, Missouri, and the approximately forty men followed the Missouri River westward. Soon they passed La Charrette, the last white settlement on the Missouri River. The expedition followed the Missouri through what is now Kansas City, Missouri, and Omaha, Nebraska. On August 20, 1804, the Corps of Discovery suffered its only death when Sergeant Charles Floyd died, apparently from acute appendicitis. He was buried at Floyd's Bluff, near what is now Sioux City, Iowa. During the final week of August, Lewis and Clark had reached the edge of the Great Plains, a place abounding with elk, deer, buffalo, and beavers. They were also entering Sioux territory.

The first tribe of Sioux they met, the Yankton Sioux, were more peaceful than their neighbors further west along the Missouri River, the Teton Sioux, also known as the Lakota. The Yankton Sioux were disappointed by the gifts they received from Lewis and Clark—five medals—and gave the explorers a warning about the upriver Teton Sioux. The Teton Sioux received their gifts with ill-disguised hostility. One chief demanded a boat from Lewis and Clark as the price to be paid for passage through their territory. As the Indians became more dangerous, Lewis and Clark prepared to fight back. At the last moment before fighting began, the two sides fell back. The Americans quickly continued westward (upriver) until winter stopped them at the Mandan tribe's territory.

In the winter of 1804–05, the party built Fort Mandan, near present-day Washburn, North Dakota. During their stay with the peaceful Mandans they were joined by a French Canadian trapper, Toussaint Charbonneau, and his Shoshone/Hidatsa wife, Sacagawea. Sacagawea had enough command of French to enable the group to talk to her Shoshone tribe as well as neighboring tribes from further west (she was the chief's sister), and to trade food for gold and jewelry. (As was common during those times, she had been taken as a slave by the Hidatsa at a young age, and reunited with her brother on the journey.) The inclusion of a woman with a young baby (Sacagawea's son, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, born in the winter of 1804-05) helped to soften tribal relations since no war-party would include a woman and baby.

In April 1805, some members of the expedition were sent back home from Mandan with them went a report about what Lewis and Clark had discovered, 108 botanical specimens (including some living animals), 68 mineral specimens, and Clark's map of the territory. Other specimens were sent back to Jefferson periodically, including a prairie dog which Jefferson received alive in a box.

The expedition continued to follow the Missouri to its headwaters and over the Continental Divide at Lemhi Pass via horses. In canoes, they descended the mountains by the Clearwater River, the Snake River, and the Columbia River, past Celilo Falls and past what is now Portland, Oregon. At this point, Lewis spotted Mt. Hood, a mountain close to the ocean. On a big pine, Clark carved, "William Clark December 3rd 1805. By land from the U.States in 1804 & 1805."[3]

Clark had written in his journal, "Ocian [sic] in view! O! The Joy!" One journal entry is captioned "Cape Disappointment" at the Entrance of the Columbia River into the Great South Sea or "Pacific Ocean." By that time the expedition faced its second bitter winter during the trip, so the group decided to vote on whether to camp on the north or south side of the Columbia River. The party agreed to camp on the south side of the river (modern Astoria, Oregon), building Fort Clatsop as their winter quarters. While wintering at the fort, the men prepared for the trip home by boiling salt from the ocean, hunting elk and other wildlife, and interacting with the native tribes. The 1805-06 winter was very rainy, and the men had a hard time finding suitable meat. Surprisingly, they never consumed much Pacific salmon.

The explorers started their journey home on March 23, 1806. On the way home, Lewis and Clark used four dugout canoes they bought from the Native Americans, plus one that they stole in "retaliation" for a previous theft. Less than a month after leaving Fort Clatsop, they abandoned their canoes because portaging around all the falls proved too difficult.

On July 3, after crossing the Continental Divide, the Corps split into two teams so Lewis could explore the Marias River. Lewis' group of four met some Blackfeet Indians. Their meeting was cordial, but during the night, the Blackfeet tried to steal their weapons. In the struggle, two Indians were killed, the only native deaths attributable to the expedition. The group of four—Lewis, Drouillard, and the Field brothers—fled over one hundred miles in a day before they camped again. Clark, meanwhile, had entered Crow territory. Lewis and Clark remained separated until they reached the confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers on August 11. While reuniting, one of Clark's hunters, Pierre Cruzatte, blind in one eye and nearsighted in the other, mistook Lewis for an elk and fired, injuring Lewis in the thigh. From there, the groups were reunited and able to quickly return home by the Missouri River. They reached St. Louis on September 23, 1806.

The Corps of Discovery returned with important information about the new United States territory and the people who lived in it, as well as its rivers and mountains, plants and animals. The expedition made a major contribution to mapping the North American continent.

France and Spain in the politics of the expedition

On December 8, 1803, Lewis met with the Spanish lieutenant governor of Upper Louisiana, Colonel Carlos Dehault Delassus. The territory was still nominally governed by Spaniards, although Spain had ceded Louisiana to France under the condition that France would not give it to a third party. Spain wanted to keep the territory as an empty buffer between the United States and the many mineral mines in northern Mexico. Thus Delassus refused to let Lewis go up the Missouri until France formally took control of the territory, at which time France would formally transfer it to the United States.

Lewis had intended to spend the winter in St. Louis since he needed to gain provisions for the trip and it was too late in the year to sensibly continue on the Missouri. Despite Lewis’ claims that the Expedition was solely a scientific one that would only travel the Missouri territory, Delassus wrote to his superiors that Lewis would undoubtedly go as far as the Pacific coast, citing that Lewis was far too competent for a lesser mission.[4]

Jefferson was willing for Lewis to winter in St. Louis rather than continue up the Missouri; Lewis could gain valuable information in St. Louis and draw from Army supplies rather than the Expedition’s. The fact that the Expedition would travel a northern route was done for political reasons. It was imperative to stay out of Spanish territory, yet this meant that the Expedition could not use the best mountain passes. Lolo Pass, which the Expedition used, would never see a wagon use it and even today it is a rough way to cross the Rockies.

After the start of the expedition, Spain sent at least four different missions to stop Lewis and Clark. During the Expedition’s stay in the Shoshone’s camps, the expedition was told they were ten days away from Spanish settlements. This warning helped Lewis and Clark stay away from the Spanish, but they never knew the Spanish had sent missions to stop them until after they returned from the journey.[5]

Achievements

- The U.S. gained an extensive knowledge of the geography of the American West in the form of maps of major rivers and mountain ranges

- Observed and described 178 plants and 122 species and subspecies of animals

- Encouraged Euro-American fur trade in the West

- Opened Euro-American diplomatic relations with the Indians

- Established a precedent for Army exploration of the West

- Strengthened the U.S. claim to Oregon Territory

- Focused U.S. and media attention on the West

- Produced a large body of literature about the West (the Lewis and Clark diaries)

Notes

- ↑ Lewis and Clark and the Revealing of America, Jefferson's Secret Message to Congress. Retrieved February 25, 2007.

- ↑ Lewis and Clark and the Revealing of America, Jefferson's Instructions for Meriwether Lewis. Retrieved February 25, 2007.

- ↑ Bernard deVoto, The Course of Empire (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1962), p. 552. ISBN 0395924987

- ↑ Ambrose, p. 122-123.

- ↑ Anthony Brandt, "Reliving Lewis and Clark: Louisiana Purchase Ceremony" (National Geographic News, March 23, 2004).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ambrose, Stephen. Undaunted Courage. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997. ISBN 0-684-82697-6

- Betts, Robert B. In Search of York: The Slave Who Went to the Pacific With Lewis and Clark. Boulder: University Press of Colorado, Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, 2002. ISBN 0-87081-714-0

- Burns, Ken. Lewis & Clark: An Illustrated History. New York: Knopf, 1997 ISBN 0-679-45450-0

- Moulton, Gary E., ed. The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8032-2950-X

- Moulton, Gary E., ed. The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002. ISBN 0-8032-2948-8

- Ronda, James P. Lewis and Clark Among the Indians. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1984. ISBN

- Schmidt, Thomas. National Geographic Guide to the Lewis & Clark Trail. Washington, DC: National Geographic, 2002. ISBN 0-7922-6471-1

External links

- "Lewis and Clark: The National Bicentennial Exhibition",Missouri Historical Society, Retrieved February 25, 2007.

- "Corps of Discovery", Lewis and Clark, Mapping the West Smithsonian Institution, Retrieved February 25, 2007.

- "Lewis and Clark Interactive Journey Log", National Geographic, Retrieved February 25, 2007.

- "The Journey of the Corp of Discovery",pbs.org, Retrieved February 25, 2007.

- "Dicovery paths", Discovering Lewis and Clark, Retrieved February 25, 2007.

- "Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail" United States National Park Service, Retrieved February 25, 2007.

- "Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail Interpretive Center" USDA Forest Center, Retrieved February 25, 2007.

- "Lewis and Clark in Kentucky", The Kentucky Lewis and Clark Bicentennial Commission, Retrieved February 25, 2007.

- "The Journals of Lewis and Clark", Sierra Club, Retrieved February 25, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.