Uexküll, Jakob von

Keisuke Noda (talk | contribs) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (28 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | [[Image:Uex photo full.jpg|thumb|Jakob Johann von Uexküll | + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{approved}}{{copyedited}} |

| − | '''Jakob Johann von Uexküll''' (September 8, 1864 - July 25, 1944) was a [[ | + | {{epname|Uexküll, Jakob von}} |

| + | [[Image:Uex photo full.jpg|thumb|Jakob Johann von Uexküll circa 1903]] | ||

| + | '''Jakob Johann von Uexküll''' (September 8, 1864 - July 25, 1944) was a Baltic German [[biology|biologist]] who made important achievements in the fields of muscular [[physiology]], animal behavior studies, and the [[cybernetics]] of [[life]]. However, his most notable achievement is the notion of ''umwelt'', used by [[Semiotics|semiotician]] [[Thomas Sebeok]]. Umwelt is the environment that a species of animal perceives according to its unique cognitive apparatus. Animal behavior can thus be best explained if the environment is understood as a sphere subjectively constituted by an animal species. Uexkull is considered as one of pioneers of [[biosemiotics]]. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Although Uexkull was neglected by main stream biologists who held a [[mechanism|mechanistic]] perspective, he was widely recognized by philosophers including [[Ernst Cassirer]], [[Ortega y Gasset]], [[Max Scheler]], [[Helmuth Plessner]], [[Arnold Gehlen]], and phenomenologists such as [[Martin Heidegger]] and [[Maurice Merleau-Ponty]]. Through Scheler, biologists such as [[Konrad Lorenz]] and [[Ludwig von Bertalanffy]] recognized the value of Uexkull's ideas. Some of his insights include early forms of [[cybernetics]] and [[system theory]]. | ||

==Life== | ==Life== | ||

| − | Jakob von Uexküll was born in Keblaste (today, Mihkli), [[Estonia]], on September 8, 1864. He studied [[zoology]], from 1884 to 1889, at the University of Dorpat (today, Tartu), and, from 1837 to 1900, | + | Jakob von Uexküll was born in Keblaste (today, Mihkli), [[Estonia]], on September 8, 1864. He studied [[zoology]], from 1884 to 1889, at the University of Dorpat (today, Tartu), and, from 1837 to 1900, [[physiology]] of animal locomotorium at the University of Heidelberg. In 1907, he received a honorary doctorate from the University of Heidelberg for his studies on muscular physiology. |

| − | Uexkull began to develop a new perspective on biology contrary to dominant [[mechanism|mechanistic]] views. He took a position similar to [[vitalism]] of [[Hans Driesch]] (1867 - 1941), and introduced | + | Uexkull began to develop a new perspective on biology contrary to dominant [[mechanism|mechanistic]] views. He took a position similar to the [[vitalism]] of [[Hans Driesch]] (1867 - 1941), and introduced the concept of [[subjectivity]] to biology; he made the claim that each species has a unique, subjective perception of its environment which determines its behavior. He further argued that the environment is not an objectively determined fixed world common to all species, but the environment is formed subjectively according to each species. In his ''Umwelt und Innenwelt der Tiere'' (1909), he labeled this subjectively perceived world of living organisms as Umwelt. |

| − | + | Uexkull took a [[Kant|Kantian]] philosophical perspective and applied it to the field of biology. As he perceived himself, his views succeeded those of Johannes Müller (1801-1858) and Karl Ernst von Baer (1792-1876). | |

| − | Due to his opposition to main stream mechanistic views, he was neglected by | + | Due to his opposition to main stream mechanistic views, he was neglected by biologists and he could not gain a position at a university. In 1924, he acquired an adjunct lecturer's position at the University of Hamburg. The university allowed him to establish the Institut für Umweltforschung, but the room was in reality a cigarette store in an aquarium.<ref>Gen Kida, ''Genshōgaku jiten = Phänomenologie'' (Tōkyō: Kōbundō, 1994, ISBN 978-4335150333) 592-593.</ref> |

| − | + | Despite this neglect, he received attention from philosophers including [[Ernst Cassirer]], [[Ortega y Gasset]], and [[Max Scheler]], and through Scheler, biologists such as [[Konrad Lorenz]] and [[Ludwig von Bertalanffy]]. Uexkull's ideas also influenced philosophers in [[philosophical anthropology]] including [[Helmuth Plessner]], [[Arnold Gehlen]], and [[phenomenology|phenomenologists]] such as [[Martin Heidegger]] and [[Maurice Merleau-Ponty]]. | |

| − | Uexkull was critical | + | Uexkull was critical of [[Nazism]] and moved to Capri island in 1940 and died there in July 25, 1944. |

His son is [[Thure von Uexküll]] and his grandson is [[Jakob von Uexkull]]. | His son is [[Thure von Uexküll]] and his grandson is [[Jakob von Uexkull]]. | ||

| Line 22: | Line 26: | ||

Uexküll became interested in how living beings subjectively [[Perception|perceive]] their [[Natural environment|environment]](s). Picture, for example, a meadow as seen through the [[compound eye]]s of a fly, continually flying through the air, and then as seen in black and white by a dog (with its highly efficient sense of smell), and then again from the point of view of a human or a blind tick. Furthermore, think of what [[time]] means to each of these different beings with their relative [[lifespan]]s. Uexküll called these [[subjective]] spatio-temporal worlds ''Umwelt''. These umwelten are distinctive from what Uexküll termed the "[[Umgebung]]" which ''would'' be [[objective]] reality were such a reality to exist. Each being perceives its own umwelt to be the objective ''Umgebung'', but this is merely perceptual bias. | Uexküll became interested in how living beings subjectively [[Perception|perceive]] their [[Natural environment|environment]](s). Picture, for example, a meadow as seen through the [[compound eye]]s of a fly, continually flying through the air, and then as seen in black and white by a dog (with its highly efficient sense of smell), and then again from the point of view of a human or a blind tick. Furthermore, think of what [[time]] means to each of these different beings with their relative [[lifespan]]s. Uexküll called these [[subjective]] spatio-temporal worlds ''Umwelt''. These umwelten are distinctive from what Uexküll termed the "[[Umgebung]]" which ''would'' be [[objective]] reality were such a reality to exist. Each being perceives its own umwelt to be the objective ''Umgebung'', but this is merely perceptual bias. | ||

| − | Uexküll's writings show a specific interest in the various worlds that exist ('conceptually') from the point of view of the Umwelt of different creatures such as [[tick]]s, [[sea urchin]]s, [[amoebae]], [[jellyfish]] and [[sea worms]] | + | Uexküll's writings show a specific interest in the various worlds that exist ('conceptually') from the point of view of the Umwelt of different creatures such as [[tick]]s, [[sea urchin]]s, [[amoebae]], [[jellyfish]] and [[sea worms]]. |

===Biosemiotics=== | ===Biosemiotics=== | ||

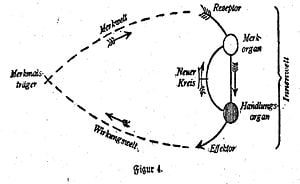

[[Image:Uexküll wirkkreis.jpg|thumb|300px|Schematic view as a early Biocybernetic]] | [[Image:Uexküll wirkkreis.jpg|thumb|300px|Schematic view as a early Biocybernetic]] | ||

| − | The [[biosemiotic]] turn in Jakob von Uexküll's analysis occurs in his discussion of | + | The [[biosemiotic]] turn in Jakob von Uexküll's analysis occurs in his discussion of an animal's relationship with its environment. The umwelt is for him an environment-world which is (according to [[Agamben]]), "constituted by a more or less broad series of elements [called] "carriers of significance" or "marks" which are the only things that interest the animal." Agamben goes on to paraphrase one example from Uexküll's discussion of a tick, saying, |

| − | <blockquote>This eyeless animal finds the way to her watchpoint [at the top of a tall blade of grass] with the help of only its skin’s general sensitivity to light. The approach of her prey becomes apparent to this blind and deaf bandit only through her sense of smell. The odor of butyric acid, which emanates from the sebaceous follicles of all mammals, works on the tick as a signal that causes her to abandon her post (on top of the blade of grass/bush) and fall blindly downward toward her prey. If she is fortunate enough to fall on something warm (which she perceives by means of an organ sensible to a precise temperature) then she has attained her prey, the warm-blooded animal, and thereafter needs only the help of her sense of touch to find the least hairy spot possible and embed herself up to her head in the cutaneous tissue of her prey. She can now slowly suck up a stream of warm blood.<ref>Quoted in Thompson | + | <blockquote>This eyeless animal finds the way to her watchpoint [at the top of a tall blade of grass] with the help of only its skin’s general sensitivity to light. The approach of her prey becomes apparent to this blind and deaf bandit only through her sense of smell. The odor of butyric acid, which emanates from the sebaceous follicles of all mammals, works on the tick as a signal that causes her to abandon her post (on top of the blade of grass/bush) and fall blindly downward toward her prey. If she is fortunate enough to fall on something warm (which she perceives by means of an organ sensible to a precise temperature) then she has attained her prey, the warm-blooded animal, and thereafter needs only the help of her sense of touch to find the least hairy spot possible and embed herself up to her head in the cutaneous tissue of her prey. She can now slowly suck up a stream of warm blood.<ref>Quoted in Nato Thompson and Christoph Cox, ''Becoming Animal: Contemporary Art in the Animal Kingdom'' (Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2005, ISBN 978-0262201612).</ref></blockquote> |

Thus, for the tick, the umwelt is reduced to only three (biosemiotic) carriers of significance: (1) The [[odor]] of [[butyric acid]], which emanates from the [[sebaceous]] follicles of all [[mammals]], (2) The [[temperature]] of 37 degrees [[celsius]] (corresponding to the [[blood]] of all mammals), (3) The hairy [[typology]] of mammals. | Thus, for the tick, the umwelt is reduced to only three (biosemiotic) carriers of significance: (1) The [[odor]] of [[butyric acid]], which emanates from the [[sebaceous]] follicles of all [[mammals]], (2) The [[temperature]] of 37 degrees [[celsius]] (corresponding to the [[blood]] of all mammals), (3) The hairy [[typology]] of mammals. | ||

==Umwelt== | ==Umwelt== | ||

| − | According to | + | According to Uexküll and [[Thomas Sebeok|Thomas A. Sebeok]], '''umwelt''' (plural: umwelten; the German word ''Umwelt'' means "environment" or "surrounding world") is the "biological foundations that lie at the very epicenter of the study of both [[communication]] and [[signification]] in the human [and non-human] animal." The term is usually translated as "self-centered world." Uexküll theorized that organisms can have different umwelten, even though they share the same environment. |

===Discussion=== | ===Discussion=== | ||

Each functional component of an umwelt has a [[Meaning (non-linguistic)|meaning]] and so represents the organism's [[model (abstract)|model]] of the world. It is also the [[semiotic]] world of the organism, including all the meaningful aspects of the world for any particular organism, i.e. it can be water, food, shelter, potential threats, or points of reference for navigation. An organism creates and reshapes its own umwelt when it interacts with the world. This is termed a 'functional circle'. The umwelt theory states that the mind and the world are inseparable, because it is the mind that interprets the world for the organism. Consequently, the umwelten of different organisms differ, which follows from the individuality and uniqueness of the history of every single organism. When two umwelten interact, this creates a [[semiosphere]]. | Each functional component of an umwelt has a [[Meaning (non-linguistic)|meaning]] and so represents the organism's [[model (abstract)|model]] of the world. It is also the [[semiotic]] world of the organism, including all the meaningful aspects of the world for any particular organism, i.e. it can be water, food, shelter, potential threats, or points of reference for navigation. An organism creates and reshapes its own umwelt when it interacts with the world. This is termed a 'functional circle'. The umwelt theory states that the mind and the world are inseparable, because it is the mind that interprets the world for the organism. Consequently, the umwelten of different organisms differ, which follows from the individuality and uniqueness of the history of every single organism. When two umwelten interact, this creates a [[semiosphere]]. | ||

| − | As a term, umwelt also unites all the semiotic processes of an organism into a whole. Internally, an organism is the sum of its parts operating in functional circles and, to survive, all the parts must work together co-operatively. This is termed the 'collective umwelt' which models the organism as a | + | As a term, umwelt also unites all the semiotic processes of an organism into a whole. Internally, an organism is the sum of its parts operating in functional circles and, to survive, all the parts must work together co-operatively. This is termed the 'collective umwelt' which models the organism as a centralized system from the cellular level upward. This requires the [[semiosis]] of any one part to be continuously connected to any other semiosis operating within the same organism. If anything disrupts this process, the organism will not operate efficiently. But, when semiosis operates, the organism exhibits goal-oriented or intentional behavior. |

| − | == | + | ==Legacy== |

| + | |||

| + | Although Uexkull was neglected by biologists while he was alive, he has received the attention of a wide range of philosophers and a new generation of biologists. Jakob von Uexküll is also considered a pioneer of [[Semiotics|semiotic]] biology, or [[biosemiotics]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Uexkull thought that the concept of Ummwelt, which he developed as a biological theory, could apply to humans as well. However, [[Max Scheler]] and [[Arnold Gehlen]], who recognized the value of Uexkull's ideas, argued that while an animal is bound by its own environment, human beings can transcend it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Nevertheless, his innovative ideas influenced those thinkers who were developing new ideas that departed from [[mechanism]] and [[positivism]]. His influence extends to [[postmodernism|postmodernists]], such as [[Gilles Deleuze]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==See also== | ||

| + | *[[Konrad Lorenz]] | ||

| + | *[[Martin Heidegger]] | ||

| + | *[[Maurice Merleau-Ponty]] | ||

| + | *[[Max Scheler]] | ||

| + | *[[Ortega y Gasset]] | ||

| + | *[[Semiotics]] | ||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

| + | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | *Agamben, Giorgio. "Chapter 10, “Umwelt”" in ''The Open: Man and Animal'', translated by Kevin Attell (Originally published in Italian in 2002 under the title ''L'aperto: l'uomo e l'animale''), Stanford, CA | + | *Agamben, Giorgio. "Chapter 10, “Umwelt”" in ''The Open: Man and Animal'', translated by Kevin Attell (Originally published in Italian in 2002 under the title ''L'aperto: l'uomo e l'animale''), Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0804747370 |

| − | *Brauckmann, Sabine | + | *Brauckmann, Sabine. "From the Haptic-Optic Space to Our Environment: Jakob Von Uexkull and Richard Woltereck." ''Semiotica''. 134(1) (2001): 293. |

| − | *Buchanan, Brett. ''Onto-Ethologies: The Animal Environments of Uexküll, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, and Deleuze.'' Albany: SUNY Press, 2008. ISBN | + | *Buchanan, Brett. ''Onto-Ethologies: The Animal Environments of Uexküll, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, and Deleuze.'' Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0791476116 |

| − | *Figge, Udo L | + | *Figge, Udo L. "Jakob Von Uexkull: Merkmale and Wirkmale." ''Semiotica''. 134(1) ( 2001): 193. |

| − | *Heusden, Barend van | + | *Heusden, Barend van. "Jakob Von Uexkull and Ernst Cassirer." ''Semiotica''. 134(1) (2001): 275. |

| − | *Kida, Gen. ''Genshōgaku jiten = Phänomenologie.'' Tōkyō: Kōbundō, 1994. ISBN | + | *Kida, Gen. ''Genshōgaku jiten = Phänomenologie.'' Tōkyō: Kōbundō, 1994. ISBN 978-4335150333 |

| − | *Kull, Kalevi | + | *Kull, Kalevi. “On Semiosis, Umwelt, and Semiosphere.” ''Semiotica'', 120(3/4) (1998): 299-310. |

| − | *Kull, Kalevi. "Special Issue Jakob Von Uexküll: A Paradigm for Biology and Semiotics." ''Semiotica'', | + | *Kull, Kalevi. "Special Issue Jakob Von Uexküll: A Paradigm for Biology and Semiotics." ''Semiotica'', 134 (1/4). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2001. |

| − | *Lagerspetz, K. Y. H | + | *Lagerspetz, K. Y. H. "Jakob Von Uexkull and the Origins of Cybernetics." ''Semiotica''. 134 (2001): 643-652. |

| − | *Patten, Bernard C | + | *Patten, Bernard C. "Jakob Von Uexkull and the Theory of Environs." ''Semiotica''. 134(1) (2001): 423. |

| − | *Sax, Boria, and Peter H Klopfer | + | *Sax, Boria, and Peter H Klopfer. "Jakob Von Uexkull and the Anticipation of Sociobiology." ''Semiotica''. 134(1) (2001): 767. |

*Schiller, Claire H., and D. J. Kuenen. ''Instinctive Behavior; The Development of a Modern Concept.'' New York: International Universities Press, 1957. | *Schiller, Claire H., and D. J. Kuenen. ''Instinctive Behavior; The Development of a Modern Concept.'' New York: International Universities Press, 1957. | ||

| − | *Thompson, Nato, and Christoph Cox. ''Becoming Animal: Contemporary Art in the Animal Kingdom.'' Cambridge, | + | *Thompson, Nato, and Christoph Cox. ''Becoming Animal: Contemporary Art in the Animal Kingdom.'' Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2005. ISBN 978-0262201612 |

| − | *Uexküll, Jakob von, and Herber Girardet. ''Shanping Our Future: Creating the World Future Council.'' RSD buchan, Vic: Wwoof Pty Ltd, 2006. ISBN | + | *Uexküll, Jakob von, and Herber Girardet. ''Shanping Our Future: Creating the World Future Council.'' RSD buchan, Vic: Wwoof Pty Ltd, 2006. ISBN 978-0646455891 |

| − | *Uexküll, Jakob von. "A Stroll Through the Worlds of Animals and Men: A Picture Book of Invisible Worlds," ''Instinctive Behavior: The | + | *Uexküll, Jakob von. "A Stroll Through the Worlds of Animals and Men: A Picture Book of Invisible Worlds," ''Instinctive Behavior: The Development of a Modern Concept'', ed. and trans. Claire H. Schiller, New York: International Universities Press, Inc., 1957. |

| − | *Uexkull, Jakob von | + | *Uexkull, Jakob von. "The New Concept of Umwelt: A Link between Science and the Humanities." ''Semiotica''. 134(1) (2001): 111. |

| − | *Ziemke, T., and N. E. Sharkey | + | *Ziemke, T., and N. E. Sharkey. "A Stroll Through the Worlds of Robots and Animals: Applying Jakob Von Uexkull's Theory of Meaning to Adaptive Robots and Artificial Life." ''Semiotica'' 134 (2001): 701-746. |

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | All links | + | All links retrieved March 14, 2018. |

* [http://www.math.uni-hamburg.de/home/rueting/UexECMTB.doc Jakob von Uexküll, Theoretical Biology, Biocybernetics and Biosemiotics (Journal article) ] | * [http://www.math.uni-hamburg.de/home/rueting/UexECMTB.doc Jakob von Uexküll, Theoretical Biology, Biocybernetics and Biosemiotics (Journal article) ] | ||

* [http://www.math.uni-hamburg.de/home/rueting/uexinhh.ppt Jakob von Uexküll and his "Institut für Umweltforschung in Hamburg" (PPT - Presentation)] | * [http://www.math.uni-hamburg.de/home/rueting/uexinhh.ppt Jakob von Uexküll and his "Institut für Umweltforschung in Hamburg" (PPT - Presentation)] | ||

| − | *[http://web.archive.org/web/20060221134707/http://www.ut.ee/SOSE/deely.htm Umwelt] by | + | *[http://web.archive.org/web/20060221134707/http://www.ut.ee/SOSE/deely.htm Umwelt] by John Deely |

| − | |||

* [http://www.math.uni-hamburg.de/home/rueting/Projekte.htm Jakob von Uexküll, Institute for theoretical biology, biocybernetics and biosemiotics] at the university of Hamburg. (German) | * [http://www.math.uni-hamburg.de/home/rueting/Projekte.htm Jakob von Uexküll, Institute for theoretical biology, biocybernetics and biosemiotics] at the university of Hamburg. (German) | ||

| − | + | ||

[[Category:Life sciences]] | [[Category:Life sciences]] | ||

Latest revision as of 20:48, 14 March 2018

Jakob Johann von Uexküll (September 8, 1864 - July 25, 1944) was a Baltic German biologist who made important achievements in the fields of muscular physiology, animal behavior studies, and the cybernetics of life. However, his most notable achievement is the notion of umwelt, used by semiotician Thomas Sebeok. Umwelt is the environment that a species of animal perceives according to its unique cognitive apparatus. Animal behavior can thus be best explained if the environment is understood as a sphere subjectively constituted by an animal species. Uexkull is considered as one of pioneers of biosemiotics.

Although Uexkull was neglected by main stream biologists who held a mechanistic perspective, he was widely recognized by philosophers including Ernst Cassirer, Ortega y Gasset, Max Scheler, Helmuth Plessner, Arnold Gehlen, and phenomenologists such as Martin Heidegger and Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Through Scheler, biologists such as Konrad Lorenz and Ludwig von Bertalanffy recognized the value of Uexkull's ideas. Some of his insights include early forms of cybernetics and system theory.

Life

Jakob von Uexküll was born in Keblaste (today, Mihkli), Estonia, on September 8, 1864. He studied zoology, from 1884 to 1889, at the University of Dorpat (today, Tartu), and, from 1837 to 1900, physiology of animal locomotorium at the University of Heidelberg. In 1907, he received a honorary doctorate from the University of Heidelberg for his studies on muscular physiology.

Uexkull began to develop a new perspective on biology contrary to dominant mechanistic views. He took a position similar to the vitalism of Hans Driesch (1867 - 1941), and introduced the concept of subjectivity to biology; he made the claim that each species has a unique, subjective perception of its environment which determines its behavior. He further argued that the environment is not an objectively determined fixed world common to all species, but the environment is formed subjectively according to each species. In his Umwelt und Innenwelt der Tiere (1909), he labeled this subjectively perceived world of living organisms as Umwelt.

Uexkull took a Kantian philosophical perspective and applied it to the field of biology. As he perceived himself, his views succeeded those of Johannes Müller (1801-1858) and Karl Ernst von Baer (1792-1876).

Due to his opposition to main stream mechanistic views, he was neglected by biologists and he could not gain a position at a university. In 1924, he acquired an adjunct lecturer's position at the University of Hamburg. The university allowed him to establish the Institut für Umweltforschung, but the room was in reality a cigarette store in an aquarium.[1]

Despite this neglect, he received attention from philosophers including Ernst Cassirer, Ortega y Gasset, and Max Scheler, and through Scheler, biologists such as Konrad Lorenz and Ludwig von Bertalanffy. Uexkull's ideas also influenced philosophers in philosophical anthropology including Helmuth Plessner, Arnold Gehlen, and phenomenologists such as Martin Heidegger and Maurice Merleau-Ponty.

Uexkull was critical of Nazism and moved to Capri island in 1940 and died there in July 25, 1944.

His son is Thure von Uexküll and his grandson is Jakob von Uexkull.

Perspective from each species

Uexküll became interested in how living beings subjectively perceive their environment(s). Picture, for example, a meadow as seen through the compound eyes of a fly, continually flying through the air, and then as seen in black and white by a dog (with its highly efficient sense of smell), and then again from the point of view of a human or a blind tick. Furthermore, think of what time means to each of these different beings with their relative lifespans. Uexküll called these subjective spatio-temporal worlds Umwelt. These umwelten are distinctive from what Uexküll termed the "Umgebung" which would be objective reality were such a reality to exist. Each being perceives its own umwelt to be the objective Umgebung, but this is merely perceptual bias.

Uexküll's writings show a specific interest in the various worlds that exist ('conceptually') from the point of view of the Umwelt of different creatures such as ticks, sea urchins, amoebae, jellyfish and sea worms.

Biosemiotics

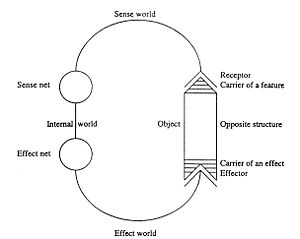

The biosemiotic turn in Jakob von Uexküll's analysis occurs in his discussion of an animal's relationship with its environment. The umwelt is for him an environment-world which is (according to Agamben), "constituted by a more or less broad series of elements [called] "carriers of significance" or "marks" which are the only things that interest the animal." Agamben goes on to paraphrase one example from Uexküll's discussion of a tick, saying,

This eyeless animal finds the way to her watchpoint [at the top of a tall blade of grass] with the help of only its skin’s general sensitivity to light. The approach of her prey becomes apparent to this blind and deaf bandit only through her sense of smell. The odor of butyric acid, which emanates from the sebaceous follicles of all mammals, works on the tick as a signal that causes her to abandon her post (on top of the blade of grass/bush) and fall blindly downward toward her prey. If she is fortunate enough to fall on something warm (which she perceives by means of an organ sensible to a precise temperature) then she has attained her prey, the warm-blooded animal, and thereafter needs only the help of her sense of touch to find the least hairy spot possible and embed herself up to her head in the cutaneous tissue of her prey. She can now slowly suck up a stream of warm blood.[2]

Thus, for the tick, the umwelt is reduced to only three (biosemiotic) carriers of significance: (1) The odor of butyric acid, which emanates from the sebaceous follicles of all mammals, (2) The temperature of 37 degrees celsius (corresponding to the blood of all mammals), (3) The hairy typology of mammals.

Umwelt

According to Uexküll and Thomas A. Sebeok, umwelt (plural: umwelten; the German word Umwelt means "environment" or "surrounding world") is the "biological foundations that lie at the very epicenter of the study of both communication and signification in the human [and non-human] animal." The term is usually translated as "self-centered world." Uexküll theorized that organisms can have different umwelten, even though they share the same environment.

Discussion

Each functional component of an umwelt has a meaning and so represents the organism's model of the world. It is also the semiotic world of the organism, including all the meaningful aspects of the world for any particular organism, i.e. it can be water, food, shelter, potential threats, or points of reference for navigation. An organism creates and reshapes its own umwelt when it interacts with the world. This is termed a 'functional circle'. The umwelt theory states that the mind and the world are inseparable, because it is the mind that interprets the world for the organism. Consequently, the umwelten of different organisms differ, which follows from the individuality and uniqueness of the history of every single organism. When two umwelten interact, this creates a semiosphere.

As a term, umwelt also unites all the semiotic processes of an organism into a whole. Internally, an organism is the sum of its parts operating in functional circles and, to survive, all the parts must work together co-operatively. This is termed the 'collective umwelt' which models the organism as a centralized system from the cellular level upward. This requires the semiosis of any one part to be continuously connected to any other semiosis operating within the same organism. If anything disrupts this process, the organism will not operate efficiently. But, when semiosis operates, the organism exhibits goal-oriented or intentional behavior.

Legacy

Although Uexkull was neglected by biologists while he was alive, he has received the attention of a wide range of philosophers and a new generation of biologists. Jakob von Uexküll is also considered a pioneer of semiotic biology, or biosemiotics.

Uexkull thought that the concept of Ummwelt, which he developed as a biological theory, could apply to humans as well. However, Max Scheler and Arnold Gehlen, who recognized the value of Uexkull's ideas, argued that while an animal is bound by its own environment, human beings can transcend it.

Nevertheless, his innovative ideas influenced those thinkers who were developing new ideas that departed from mechanism and positivism. His influence extends to postmodernists, such as Gilles Deleuze.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Gen Kida, Genshōgaku jiten = Phänomenologie (Tōkyō: Kōbundō, 1994, ISBN 978-4335150333) 592-593.

- ↑ Quoted in Nato Thompson and Christoph Cox, Becoming Animal: Contemporary Art in the Animal Kingdom (Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2005, ISBN 978-0262201612).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Agamben, Giorgio. "Chapter 10, “Umwelt”" in The Open: Man and Animal, translated by Kevin Attell (Originally published in Italian in 2002 under the title L'aperto: l'uomo e l'animale), Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0804747370

- Brauckmann, Sabine. "From the Haptic-Optic Space to Our Environment: Jakob Von Uexkull and Richard Woltereck." Semiotica. 134(1) (2001): 293.

- Buchanan, Brett. Onto-Ethologies: The Animal Environments of Uexküll, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty, and Deleuze. Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0791476116

- Figge, Udo L. "Jakob Von Uexkull: Merkmale and Wirkmale." Semiotica. 134(1) ( 2001): 193.

- Heusden, Barend van. "Jakob Von Uexkull and Ernst Cassirer." Semiotica. 134(1) (2001): 275.

- Kida, Gen. Genshōgaku jiten = Phänomenologie. Tōkyō: Kōbundō, 1994. ISBN 978-4335150333

- Kull, Kalevi. “On Semiosis, Umwelt, and Semiosphere.” Semiotica, 120(3/4) (1998): 299-310.

- Kull, Kalevi. "Special Issue Jakob Von Uexküll: A Paradigm for Biology and Semiotics." Semiotica, 134 (1/4). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2001.

- Lagerspetz, K. Y. H. "Jakob Von Uexkull and the Origins of Cybernetics." Semiotica. 134 (2001): 643-652.

- Patten, Bernard C. "Jakob Von Uexkull and the Theory of Environs." Semiotica. 134(1) (2001): 423.

- Sax, Boria, and Peter H Klopfer. "Jakob Von Uexkull and the Anticipation of Sociobiology." Semiotica. 134(1) (2001): 767.

- Schiller, Claire H., and D. J. Kuenen. Instinctive Behavior; The Development of a Modern Concept. New York: International Universities Press, 1957.

- Thompson, Nato, and Christoph Cox. Becoming Animal: Contemporary Art in the Animal Kingdom. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2005. ISBN 978-0262201612

- Uexküll, Jakob von, and Herber Girardet. Shanping Our Future: Creating the World Future Council. RSD buchan, Vic: Wwoof Pty Ltd, 2006. ISBN 978-0646455891

- Uexküll, Jakob von. "A Stroll Through the Worlds of Animals and Men: A Picture Book of Invisible Worlds," Instinctive Behavior: The Development of a Modern Concept, ed. and trans. Claire H. Schiller, New York: International Universities Press, Inc., 1957.

- Uexkull, Jakob von. "The New Concept of Umwelt: A Link between Science and the Humanities." Semiotica. 134(1) (2001): 111.

- Ziemke, T., and N. E. Sharkey. "A Stroll Through the Worlds of Robots and Animals: Applying Jakob Von Uexkull's Theory of Meaning to Adaptive Robots and Artificial Life." Semiotica 134 (2001): 701-746.

External links

All links retrieved March 14, 2018.

- Jakob von Uexküll, Theoretical Biology, Biocybernetics and Biosemiotics (Journal article)

- Jakob von Uexküll and his "Institut für Umweltforschung in Hamburg" (PPT - Presentation)

- Umwelt by John Deely

- Jakob von Uexküll, Institute for theoretical biology, biocybernetics and biosemiotics at the university of Hamburg. (German)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.