Difference between revisions of "Hecate" - New World Encyclopedia

({{Contracted}}) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (24 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Approved}}{{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} |

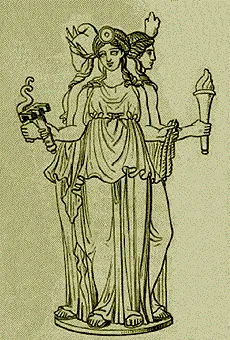

| + | [[Image:Hécate - Mallarmé.png|thumb|right|The Greek goddess Hecate shown here in her omniscient, three-faced form. Drawing by Stephane Mallarmé in ''Les Dieux Antiques, nouvelle mythologie illustrée'' in Paris, 1880.]] | ||

| + | Among the [[Ancient Greece|ancient Greeks]], '''Hecate''' or ''Hekate'' was originally a goddess of the wilderness and childbirth, who, over time, became associated with the practice of [[sorcery]]. Originally venerated as a mother goddess by the Greeks, the character of Hecate changed considerably, as her fertility and motherhood elements decreased in importance. Instead, she was ultimately transformed into a goddess of sorcery, who came to be known as the 'Queen of Ghosts', a transformation that was particularly pronounced in Ptolemaic [[Alexandria]]. It was in this sinister guise that she was transmitted to post-Renaissance culture. Today, she is often seen as a goddess of [[witchcraft]] and [[Wicca]]. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Hecate, like many of the other non-indigenous Greek gods (including [[Dionysus]], [[Demeter]], and [[Artemis]]), had a wide range of meanings and associations in the [[Greek mythology|mythic]] and [[Religion|religious]] beliefs and practices of the ancient Hellenes. She, in particular, was associated with nature and fertility, the crossroads, and (later) death, spirits, magic and the moon. In the religious practices based upon her later characterization, much like the worship of [[Anubis]] (in [[Egyptian Mythology]]) and [[Hel]] (in [[Norse Mythology]]), veneration was prompted by a fundamental human drive: to control (or at least comprehend) our mortality. Since the Greek understanding of the afterlife was a rather dreary one (See [[Hades]]), Hecate's multifaceted personality was understandably complex leading to her later magical associations. | ||

| − | + | ==Origins and Mythology== | |

| + | Hecate is known as a Greek goddess but worship of her originated among the Carians of Anatolia.<ref> Walter Burkert, ''Greek Religion: Archaic and Classical.'' (Oxford, UK: Blackwell. 1987), 171</ref> Indeed, the earliest inscription describing the goddess has been found in late archaic Miletus, close to Caria, where Hecate is a protector of entrances.<ref>Theodor Kraus. ''Hekate: Studien zu Wesen u. Bilde der Göttin in Kleinasien u. Griechenland.'' (Heidelberg, 1960), 12.</ref> | ||

| − | + | ===Birth and fundamental nature=== | |

| − | + | As Hecate was a pre-Olympian chthonic goddess (and, as such, related to earth, fertility, and death), she was not easily assimilated into the Greek pantheon. Indeed, her representation in the mythic corpus is patchy at best, with many sources describing her in a very limited fashion (if at all). This situation is further complicated by the fact that her two characterizations (goddess of nature/fertility versus goddess of death, magic and the underworld) seem to be almost entirely disparate.<ref>H. J. Rose. ''A Handbook of Greek Mythology.'' (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1959), 121-122.</ref> Indeed, outside of [[Hesiod]]'s ''Theogony,'' the classical Greek sources are relatively taciturn concerning her parentage and her relations in the Greek pantheon. | |

| − | == | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In Hesiod's masterful poem, he records that the goddess was the offspring of two Titans, Asteria and Persus. Further, he ascribes to Hecate such wide-ranging and fundamental powers, that it is hard to resist seeing such a deity as a figuration of the Great Goddess, though as a good Hellene, Hesiod ascribes her powers to a "gift" from [[Zeus]]: | |

| + | :Asteria of happy name, whom Perses once led to his great house to be called his dear wife. And she conceived and bare Hecate whom Zeus the son of Cronos honored above all. He gave her splendid gifts, to have a share of the earth and the unfruitful sea. She received honor also in starry heaven, and is honored exceedingly by the deathless gods…. The son of Cronos did her no wrong nor took anything away of all that was her portion among the former Titan gods: but she holds, as the division was at the first from the beginning, privilege both in earth, and in heaven, and in sea (''Theogony'' 404-452). | ||

| + | His inclusion and praise of Hecate in ''[[Theogony]]'' is troublesome for scholars in that he seems fulsomely to praise her attributes and responsibilities in the ancient cosmos even though she is both relatively minor and foreign. It is theorized <ref>Sarah Iles Johnston. ''Restless Dead: Encounters Between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece.'' (1991)</ref> that Hesiod’s original village had a substantial Hecate following and that his inclusion of her in the Theogony was his own way to boost the popularity of the local cult with an unfamiliar audience. | ||

| − | + | Despite her provenance as a Titaness, Hecate was acknowledged as an ally and friend of the Olympians. Indeed, she was thought to have been the only Titan to aided Zeus and the younger generation of gods in the [[Titanomachia|battle of gods and Titans]], which explains why she was not banished into the underworld realms after their defeat. In spite of the fact that no classical sources depicting the event have survived, it is attested to in considerable detail in both sculpture and pottery from the period (most namely, the majestic frieze on the altar at Pergamos.<ref>William Berg, "Hecate: Greek or 'Anatolian'?" ''Numen'' 21 (Fasc. 2) (August 1974): 129, 139.</ref> Additionally, as Hecate’s cult grew, her figure was added to the myth of the birth of Zeus<ref>Johnston (1991)</ref> as one of the midwives that hid the divine child, while [[Cronus]] consumed the swaddled rock deceitfully handed to him by [[Gaia (mythology)|Gaia]]. | |

| − | + | Conversely, other sources describe her as the child of either Zeus and Asteria, Aristaios and Asteria, or even Zeus and Demeter.<ref>Gantz, 26.</ref> This final association likely arose due to a similarity of function, as both goddesses were related to earth and fertility.<ref>These associations were especially prominent in rural areas. See: Jon D. Mikalson. ''Ancient Greek Religion.'' (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2005), 215, 217.</ref> | |

| − | == | + | ===Relationship with humanity=== |

| − | + | In keeping with the extremely positive image of the goddess expounded upon in the ''Theogony,'' Hesiod also describes the multifarious and all-encompassing contributions that the goddess makes to the lives of mortal. As he suggests: | |

| + | :Whom she will she greatly aids and advances: she sits by worshipful kings in judgment, and in the assembly whom her will is distinguished among the people. And when men arm themselves for the battle that destroys men, then the goddess is at hand to give victory and grant glory readily to whom she will. Good is she also when men contend at the games, for there too the goddess is with them and profits them: and he who by might and strength gets the victory wins the rich prize easily with joy, and brings glory to his parents. And she is good to stand by horsemen, whom she will: and to those whose business is in the grey discomfortable sea, and who pray to Hecate and [[Poseidon|the loud-crashing Earth-Shaker]], easily the glorious goddess gives great catch, and easily she takes it away as soon as seen, if so she will. She is good in the byre with Hermes to increase the stock. The droves of kine and wide herds of goats and flocks of fleecy sheep, if she will, she increases from a few, or makes many to be less. (''Theogony'' 404-452). | ||

| − | [[ | + | ===Disparate Understandings of Hecate=== |

| + | ====Hecate and Artemis==== | ||

| + | As in the case of her lineage, there are also multiple understandings of the mythic role(s) of the goddess. One lesser role subordinates Hecate to the goddess [[Artemis]]. In this version,<ref>Johnston (1991)</ref> Hecate is a mortal priestess who is commonly associated with [[Iphigeneia]] and scorns and insults Artemis, but is eventually driven to suicide. In a uncharacteristic gesture of forgiveness, Artemis then adorns the dead body with jewelry and whispers for her spirit to rise and become her Hecate, and act similar to [[Nemesis]] as an avenging spirit for injured women. Such myths, where a local god sponsors or ‘creates’ a foreign god, were widespread in ancient cultures as they allowed a syncretistic means of integrating foreign cults.<ref>Rose (1959)</ref>and <ref>Lewis Richard Farnell. ''The Cults of the Greek States,'' (Vol. 2), (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1907), | ||

| + | 508-509, 515-519, also comment on the relationship between the two deities.</ref> | ||

| − | + | ==== Goddess of the crossroads ==== | |

| + | Similar to the ''herms'' of classic antiquity (totems of Hermes placed at borders as wards against danger), images of Hecate also fulfilled the same liminal and protective role. It became common to place statues of the goddess at the gates of cities, and eventually domestic doorways. Further, Hecate had a special role at three-way crossroads, where the Greeks set poles with masks of each of her heads facing different directions.<ref>Rose, 121-122</ref> <ref>Martin Puhvel, "The Mystery of the Cross-Roads," ''Folklore'' 87(2) (1976): 175.</ref> Eventually, this led to the depiction of the goddess as possessing three heads (or even three conjoined bodies ([[#Representations|see below]])). | ||

| − | + | The crossroad aspect of Hecate likely stems from her original sphere of influence as a goddess of the wilderness and untamed areas. This led to sacrifice in order for safe travel into these areas. | |

| − | + | The later [[Roman mythology|Roman]] version of this deity is as the goddess ''Trivia,'' "the three ways." [[Eligius]] in the seventh century reminded his recently converted flock in Flanders that "No Christian should make or render any devotion to the gods of the trivium, where three roads meet, to the fanes or the rocks, or springs or groves or corners," worship practices that had been common in his [[Celtic]] congregation.<ref>See the ''Vita'' of Saint Eligius at [http://www.northvegr.org/lore/germanic/e.php northvegr.org]. Retrieved June 23, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Over time, the apotropaic associations with the goddess, specifically with respect to her role in driving away evil spirits, led to the belief that Hecate, if offended, could summon evil spirits. Thus, invocations to Hecate arose which characterized her as the governess of the borders between the mortal world and the spirit world <ref>Johnston (1991)</ref>. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==== Goddess of magic, sorcery and the dead ==== | |

| + | In the modern imagination, Hecate is most often remembered as a chthonic goddess, associated with sorcery, necromancy and the mysteries of the dead. Indeed, Hecate was the goddess who appeared most often in magical texts such as the Greek Magical [[Papyri]] and [[curse tablet]]s, along with [[Hermes]]. The transformation of the figure of Hekate can be traced to fifth-century Athens, as in two fragments of [[Aeschylus]] (ca. 525–456 B.C.E.) she appears as a great goddess, while in [[Sophocles]] (495-406 B.C.E.) and [[Euripides]] (480–406 B.C.E.) she has already become the mistress of witchcraft and ''keres.''<ref>Gantz, 26-27. </ref> <ref>Farnell (Vol. II), 510-513.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Eventually, Hecate’s power resembled that of sorcery. [[Medea]], who was a priestess of Hecate, used witchcraft in order to handle magic herbs and poisons with skill, and to be able to stay the course of rivers, or check the paths of the stars and the moon.<ref>See: Euripides, [[Medea]] </ref><ref>Apollonius Rhodius, ''Argonautica''</ref><ref> Apollodorus, ''The Library.'' </ref> | |

| − | + | These chthonic associations would developed through a relatively late affiliation with the tale of [[Persephone]]'s abduction by [[Hades]]. Specifically, the [[Homeric]] ''Hymn to Demeter'' suggests that Hecate was one of the two gods (along with all-seeing [[Helios]]) who were witness to the young goddess's kidnapping, and who accompanies [[Demeter]] (the grieving mother) in her quest to return her daughter to the world of the living. When the two are finally reunited, they are described given due thanks to the shadowy goddess: | |

| + | :Then bright-coiffed Hecate came near to them, and often did she embrace the daughter of holy Demeter: and from that time the lady Hecate was minister and companion to Persephone (''Homeric Hymn to Demeter,'' 438-440).<ref>Homer. ''Homeric Hymn to Demeter.'' accessed online at [http://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/homer/hymns.htm sacred-texts.com]. Retrieved June 23, 2007.</ref> | ||

| − | + | This connection with the world of the dead is even further established by the time of [[Vergil]]'s composition of the ''[[Aeneid]],'' which (in Book 6) describes the hero's visit to the Underworld. When visiting this grim twilight realm, the protagonist is apprised of the various tortures being visited on the souls of the impious and immoral dead, all under the watchful eye of Hecate.<ref>Barry B. Powell. ''Classical Myth,'' Second Edition. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1998), 300, 301</ref> | |

| − | The | + | ==Representations== |

| + | [[Image:William Blake 006.jpg|300px|right|Depiction of Hecate by [[William Blake]].]] | ||

| + | The earliest depictions of Hecate are single faced, not triplicate. Summarizing the early trends in artistic depictions of the goddess, Lewis Richard Farnell writes: | ||

| + | :The evidence of the monuments as to the character and significance of Hekate is almost as full as that of the literature. But it is only in the later period that they come to express her manifold and mystic nature. Before the fifth century there is little doubt that she was usually represented as of single form like any other divinity, and it was thus that the [[Hesiod|Boeotian poet]] ([Hesiod]) imagined her, as nothing in his verses contains any allusion to a triple formed goddess. The earliest known monument is a small terracotta found in Athens, with a dedication to Hekate (Plate XXXVIII. a), in writing of the style of the sixth century. The goddess is seated on a throne with a chaplet bound round her head; she is altogether without attributes and character, and the only value of this work, which is evidently of quite a general type and gets a special reference and name merely from the inscription, is that it proves the single shape to be her earlier from, and her recognition at Athens to be earlier than the Persian invasion.<ref>Lewis Richard Farnell, "Hecate in Art," ''The Cults of the Greek States.'' (Oxford, UK: [[Oxford University Press]], 1896).</ref> | ||

| − | The | + | The second-century traveler [[Pausanias (geographer)|Pausanias]] stated that Hecate was first depicted in triplicate by the sculptor [[Alkamenes]] in the Greek Classical period of the late fifth century. Some classical portrayals, depict her in this form holding a torch, a key and a serpent. Others continue to depict her in singular form. Hecate's triplicity is represented in the vast frieze of the great Pergamon Altar, which depicts the ''[[Titanomachy]]'' (the mythic battle between the Olympians and the Titans). In the [[Argos|Argolid]], near the shrine of the Dioscuri, Pausanias also tells of a temple of Hecate opposite the sanctuary of Eilethyia: "The image is a work of Scopas. This one is of stone, while the bronze images opposite, also of Hekate, were made respectively by Polycleitus and his brother Naucydes, son of Mothon."<ref>Pausanius, ''Description of Greece'' ii.22.7, W. H. S. Jones translation accessible online at [http://www.theoi.com/Text/Pausanias1A.html theoi.com]. Retrieved June 23, 2007. See also: Gantz, 27.</ref> |

| − | + | In general, the representations of Hecate seem to follow a similar progression to the development of her cultic and mythic forms, evolving in tandem with the public conception of the goddess. Thus, as her characterization began to assume greater elements of the chthonic and the uncanny, visual representations followed suit.<ref>For an excellent overview of the evolution of Hecate in sculpture, see Charles M. Edwards, "The Running Maiden from Eleusis and the Early Classical Image of Hekate," ''American Journal of Archaeology'' 90(3), (July 1986): 307-318.</ref> | |

| − | + | ==Cult of Hecate== | |

| + | As mentioned above, and in spite of the ubiquity of popular belief in the goddess, Hecate was not originally a Greek deity. Instead, the roots of her veneration seem to stem from the Carians of Asia Minor.<ref>Kraus (1960)</ref> More specifically, her most important sanctuary was [[Lagina]], a theocratic city-state where the goddess was served by [[eunuch]]s, and was celebrated through sacrifices and festivals.<ref>Burkert </ref> At this temple, "the goddess was worshipped as ''sōteira,'' ''mēgiste,'' and ''epiphanestatē''; her exalted rank and function here are unmatched in cults of Hecate elsewhere"<ref>Berg, 128 </ref> <ref> See also: Kraus, 12.</ref> Moreover, this influence was such that she was also seen as the patroness of nearby Stratonikea.<ref>Strabo, ''Geography'' (xiv.2.25)</ref> ; <ref> Kraus (1960)</ref> The case for Hecate's origin's in Anatolia is bolstered by the fact that this is the only region where theophoric names incorporating "Hecate" are attested.<ref>See: Kraus, (1960) as he offers the first comprehensive modern discussion of Hecate in monuments and material culture.</ref> | ||

| − | + | This type of organized temple observance is attested to in Hesiod's ''Theogony'': | |

| + | :For to this day, whenever any one of men on earth offers rich sacrifices and prays for favor according to custom, he calls upon Hecate. Great honor comes full easily to him whose prayers the goddess receives favorably, and she bestows wealth upon him; for the power surely is with her (404-452).<ref>Hesiod, ''Theogony,'' accessed online at [http://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/hesiod/theogony.htm sacred-texts.com]. Retrieved June 23, 2007.</ref> | ||

| + | In Thrace, on the other hand, she played a role similar to that of lesser-[[Hermes]], namely a governess of liminal points and the wilderness, bearing little resemblance to the night-walking crone that she became. | ||

| − | + | As her cult spread into other areas of Greece,<ref>See [http://www.theoi.com/Cult/HekateCult.html theoi.com] for an excellent overview of the various classical texts that mention the worship of the goddess (in its various forms).</ref> it led to a theological conflict, as Hecate’s role was already filled by other more prominent gods in the Greek pantheon, above all by [[Artemis]], and by more archaic figures, such as [[Nemesis (mythology)|Nemesis]]. It was likely at this time that her associations with death and magic developed, as these were domains that were relatively under-represented in the Olympic Pantheon. | |

| − | + | In this role, Hecate was seen as able to use her chthonic powers to deliver spiritual punishment to moral wrong-doers. Using "curse tablets," which were buried in the ground, supplicants requested the aid of the goddess in pursuing their interpersonal vendettas, many of which have subsequently been discovered through archaeological research. One example has been found that references a legal battle with an individual named Phrerenicus: | |

| − | Hecate is | + | :Let Pherenicus be bound before Hermes Chthonios and Hecate Chthonia. … And just as the lead is held in no esteem and is cold, so may Pherenicus and his things be held in no esteem and be cold, and so for the things which Pherenicus' collaborators say and plot concerning me.<ref>Quoted in Price, 101-102.</ref> <ref>See also: Mikalson, 38. </ref> |

| + | Further, this association with evil spirits led to an increase in her worship at the household level. For instance, one practice (poetically described as the ''banquet of Hekate'') referred to "offerings made … to the mistress of spirits, in order to avert evil phantoms from the house. None of the household would touch the food."<ref>Farnell (Vol. II), 511.</ref> To this end, worshipers fearing the taint of evil or contagion would occasionally sacrifice a dog at the crossroads, also meaning to placate the "mistress of ghosts."<ref>Farnell (Vol. II), 515.</ref> | ||

| − | + | ===Festivals=== | |

| + | Hecate was worshiped by both the Greeks and the Romans who had their own festivals dedicated to her. According to Ruickbie, the Greeks observed two days sacred to Hecate, one on the 13th of August and one on the 30th of November, whilst the Romans observed the 29th of every month as her sacred day.<ref>Leo Ruickbie. ''Witchcraft Out of the Shadows: A Complete History.'' (London, UK: Robert Hale, 2004), 19.</ref> Further, the household observances (described above) always took place on the "thirtieth day [of the month], which was sacred to the dead."<ref>Farnell (Vol. II), 511.</ref> | ||

| − | == | + | ==Cross-cultural parallels== |

| − | + | The figure of Hecate can often be associated with the figure of [[Isis]] in Egyptian myth, mainly due to her relationship with esoteric knowledge. In Hebrew myth, she is often compared to the figure of [[Lilith]] and to the Whore of Babylon, in later Christian tradition. Both were symbols of liminal points, with Lilith also playing a role in sorcery. She is also comparable to [[Hel]] of Nordic myth in her underworld function. | |

| − | + | Before she became associated with Greek mythology, she had many similarities with [[Artemis]] (wilderness, and watching over wedding ceremonies) and [[Hera]] (child rearing and the protection of young men or heroes, and watching over wedding ceremonies). | |

| − | == | + | == Epithets == |

| − | |||

*''Chthonian'' (Earth/Underworld goddess) | *''Chthonian'' (Earth/Underworld goddess) | ||

| − | |||

*''Enodia'' (Goddess of the paths) | *''Enodia'' (Goddess of the paths) | ||

*''Antania'' (Enemy of mankind) | *''Antania'' (Enemy of mankind) | ||

| − | *'' | + | *''[[Artemis]]'' of the crossroads |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

*''Phosphoros'' (the light-bringer) | *''Phosphoros'' (the light-bringer) | ||

| − | *''Soteira'' (" | + | *''Soteira'' ("Savior") |

| − | *'' | + | *''Trioditis'' (Gr.) |

| − | * | + | *''Trivia'' (Latin: Goddess of Three Roads) |

*''Klêidouchos'' (Keeper of the Keys) | *''Klêidouchos'' (Keeper of the Keys) | ||

| − | *''Tricephalus'' or ''Triceps'' (The Three-Headed) | + | *''Tricephalus'' or ''Triceps'' (The Three-Headed)<ref>For an excellent listing of poetic and cultic epithets, see [http://www.theoi.com/Cult/HekateCult.html theoi.com]. Retrieved June 23, 2007.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | see | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| Line 148: | Line 96: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | + | * Apollodorus. ''Gods & Heroes of the Greeks,'' Translated and with an Introduction and Notes by Michael Simpson. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1977. ISBN 0870232053. |

| − | * Lewis Richard | + | * Burkert, Walter. ''Greek Religion: Archaic and Classical,'' Translated by John Raffan. Oxford: Blackwell, 1985. ISBN 0631112413. |

| − | *Johnston, Sarah Iles | + | * Berg, William. "Hecate: Greek or 'Anatolian'?" ''Numen'' 21 (Fasc. 2) (August 1974): 128-140. |

| − | * | + | * Dillon, Matthew. ''Pilgrims and Pilgrimage in Ancient Greece.'' London; New York: Routledge, 1997. ISBN 0415127750. |

| − | * | + | * Edwards, Charles M. "The Running Maiden from Eleusis and the Early Classical Image of Hekate." ''American Journal of Archaeology'' 90(3) (July 1986): 307-318. |

| − | * | + | * Farnell, Lewis Richard. ''The Cults of the Greek States.'' (in Five Volumes). Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1907. |

| − | * | + | * __________. "Hecate in Art," ''The Cults of the Greek States.'' Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1896. |

| − | * | + | * Johnston, Sarah Iles. ''Hekate Soteira: A Study of Hekate's Role in the Chaldean Oracles and Related Literature.'' An American Philological Association Book: 1990. ISBN 1555404278 |

| − | * | + | * __________. ''Restless Dead: Encounters Between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece.'' University of California Press: 1991. ISBN 0520217071 |

| + | * Kerenyi, Karl. ''The Gods of the Greeks.'' London & New York: Thames and Hudson, 1951. ISBN 0500270481 | ||

| + | * Kraus, Theodor. ''Hekate: Studien zu Wesen u. Bilde der Göttin in Kleinasien u. Griechenland.'' Heidelberg, 1960. (in German) | ||

| + | * Mikalson, Jon D. ''Ancient Greek Religion.'' Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2005. ISBN 0631232222. | ||

| + | * Parke, H. W. ''Festivals of the Athenians.'' Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1977. ISBN 0801410541. | ||

| + | * Powell, Barry B. ''Classical Myth,'' Second Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1998. ISBN 0137167148. | ||

| + | * Puhvel, Martin. "The Mystery of the Cross-Roads." ''Folklore'' 87(2) (1976): 167-177. | ||

| + | * Rose, H. J. ''A Handbook of Greek Mythology.'' New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1959. ISBN 0525470417 | ||

| + | * Ruickbie, Leo. ''Witchcraft Out of the Shadows: A Complete History.'' London, UK: Robert Hale, 2004. ISBN 0709075677 | ||

| + | * Salmonson, Jessica Amanda. ''The Encyclopedia of Amazons.'' Saint Paul, MN: Paragon House, 1991. ISBN 1557784205 | ||

| + | * Vol, Mary. "Athene (Athena) and Artemis." in Seppo Sakari Telenius. ''Athena-Artemis.'' Helsinki: Kirja kerrallaan, 2005 and 2006. ISBN 9529205600 | ||

| + | * Ventris, Michael and John Chadwick. ''Documents in Mycenaean Greek,'' Second Edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1973. ISBN 0521085586.. | ||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved December 12, 2017. | |

| − | *[http://www.goddessgift.com/goddess-myths/greek_goddess_hecate.htm Myths of the Greek Goddess Hecate] | + | *[http://www.goddessgift.com/goddess-myths/greek_goddess_hecate.htm Myths of the Greek Goddess Hecate] - |

| − | + | *[http://www.theoi.com/Khthonios/Hekate.html Theoi Project, Hecate] classical literary sources and art - | |

| − | + | *[http://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/hesiod/theogony.htm Hesiod, ''Theogony, Works and Days''. An English translation] | |

| − | + | *[http://www.granta.demon.co.uk/arsm/jg/hekate.html Hekate in Greek esotericism]: Ptolemaic and Gnostic transformations of Hecate | |

| − | *[http://www.theoi.com/Khthonios/Hekate.html Theoi Project, Hecate] classical literary sources and art | ||

| − | *[http://www. | ||

| − | *[http://www.granta.demon.co.uk/arsm/jg/hekate.html Hekate in Greek esotericism]: Ptolemaic and Gnostic transformations of Hecate | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:Philosophy and religion]] | [[Category:Philosophy and religion]] | ||

Latest revision as of 17:38, 12 December 2017

Among the ancient Greeks, Hecate or Hekate was originally a goddess of the wilderness and childbirth, who, over time, became associated with the practice of sorcery. Originally venerated as a mother goddess by the Greeks, the character of Hecate changed considerably, as her fertility and motherhood elements decreased in importance. Instead, she was ultimately transformed into a goddess of sorcery, who came to be known as the 'Queen of Ghosts', a transformation that was particularly pronounced in Ptolemaic Alexandria. It was in this sinister guise that she was transmitted to post-Renaissance culture. Today, she is often seen as a goddess of witchcraft and Wicca.

Hecate, like many of the other non-indigenous Greek gods (including Dionysus, Demeter, and Artemis), had a wide range of meanings and associations in the mythic and religious beliefs and practices of the ancient Hellenes. She, in particular, was associated with nature and fertility, the crossroads, and (later) death, spirits, magic and the moon. In the religious practices based upon her later characterization, much like the worship of Anubis (in Egyptian Mythology) and Hel (in Norse Mythology), veneration was prompted by a fundamental human drive: to control (or at least comprehend) our mortality. Since the Greek understanding of the afterlife was a rather dreary one (See Hades), Hecate's multifaceted personality was understandably complex leading to her later magical associations.

Origins and Mythology

Hecate is known as a Greek goddess but worship of her originated among the Carians of Anatolia.[1] Indeed, the earliest inscription describing the goddess has been found in late archaic Miletus, close to Caria, where Hecate is a protector of entrances.[2]

Birth and fundamental nature

As Hecate was a pre-Olympian chthonic goddess (and, as such, related to earth, fertility, and death), she was not easily assimilated into the Greek pantheon. Indeed, her representation in the mythic corpus is patchy at best, with many sources describing her in a very limited fashion (if at all). This situation is further complicated by the fact that her two characterizations (goddess of nature/fertility versus goddess of death, magic and the underworld) seem to be almost entirely disparate.[3] Indeed, outside of Hesiod's Theogony, the classical Greek sources are relatively taciturn concerning her parentage and her relations in the Greek pantheon.

In Hesiod's masterful poem, he records that the goddess was the offspring of two Titans, Asteria and Persus. Further, he ascribes to Hecate such wide-ranging and fundamental powers, that it is hard to resist seeing such a deity as a figuration of the Great Goddess, though as a good Hellene, Hesiod ascribes her powers to a "gift" from Zeus:

- Asteria of happy name, whom Perses once led to his great house to be called his dear wife. And she conceived and bare Hecate whom Zeus the son of Cronos honored above all. He gave her splendid gifts, to have a share of the earth and the unfruitful sea. She received honor also in starry heaven, and is honored exceedingly by the deathless gods…. The son of Cronos did her no wrong nor took anything away of all that was her portion among the former Titan gods: but she holds, as the division was at the first from the beginning, privilege both in earth, and in heaven, and in sea (Theogony 404-452).

His inclusion and praise of Hecate in Theogony is troublesome for scholars in that he seems fulsomely to praise her attributes and responsibilities in the ancient cosmos even though she is both relatively minor and foreign. It is theorized [4] that Hesiod’s original village had a substantial Hecate following and that his inclusion of her in the Theogony was his own way to boost the popularity of the local cult with an unfamiliar audience.

Despite her provenance as a Titaness, Hecate was acknowledged as an ally and friend of the Olympians. Indeed, she was thought to have been the only Titan to aided Zeus and the younger generation of gods in the battle of gods and Titans, which explains why she was not banished into the underworld realms after their defeat. In spite of the fact that no classical sources depicting the event have survived, it is attested to in considerable detail in both sculpture and pottery from the period (most namely, the majestic frieze on the altar at Pergamos.[5] Additionally, as Hecate’s cult grew, her figure was added to the myth of the birth of Zeus[6] as one of the midwives that hid the divine child, while Cronus consumed the swaddled rock deceitfully handed to him by Gaia.

Conversely, other sources describe her as the child of either Zeus and Asteria, Aristaios and Asteria, or even Zeus and Demeter.[7] This final association likely arose due to a similarity of function, as both goddesses were related to earth and fertility.[8]

Relationship with humanity

In keeping with the extremely positive image of the goddess expounded upon in the Theogony, Hesiod also describes the multifarious and all-encompassing contributions that the goddess makes to the lives of mortal. As he suggests:

- Whom she will she greatly aids and advances: she sits by worshipful kings in judgment, and in the assembly whom her will is distinguished among the people. And when men arm themselves for the battle that destroys men, then the goddess is at hand to give victory and grant glory readily to whom she will. Good is she also when men contend at the games, for there too the goddess is with them and profits them: and he who by might and strength gets the victory wins the rich prize easily with joy, and brings glory to his parents. And she is good to stand by horsemen, whom she will: and to those whose business is in the grey discomfortable sea, and who pray to Hecate and the loud-crashing Earth-Shaker, easily the glorious goddess gives great catch, and easily she takes it away as soon as seen, if so she will. She is good in the byre with Hermes to increase the stock. The droves of kine and wide herds of goats and flocks of fleecy sheep, if she will, she increases from a few, or makes many to be less. (Theogony 404-452).

Disparate Understandings of Hecate

Hecate and Artemis

As in the case of her lineage, there are also multiple understandings of the mythic role(s) of the goddess. One lesser role subordinates Hecate to the goddess Artemis. In this version,[9] Hecate is a mortal priestess who is commonly associated with Iphigeneia and scorns and insults Artemis, but is eventually driven to suicide. In a uncharacteristic gesture of forgiveness, Artemis then adorns the dead body with jewelry and whispers for her spirit to rise and become her Hecate, and act similar to Nemesis as an avenging spirit for injured women. Such myths, where a local god sponsors or ‘creates’ a foreign god, were widespread in ancient cultures as they allowed a syncretistic means of integrating foreign cults.[10]and [11]

Goddess of the crossroads

Similar to the herms of classic antiquity (totems of Hermes placed at borders as wards against danger), images of Hecate also fulfilled the same liminal and protective role. It became common to place statues of the goddess at the gates of cities, and eventually domestic doorways. Further, Hecate had a special role at three-way crossroads, where the Greeks set poles with masks of each of her heads facing different directions.[12] [13] Eventually, this led to the depiction of the goddess as possessing three heads (or even three conjoined bodies (see below)).

The crossroad aspect of Hecate likely stems from her original sphere of influence as a goddess of the wilderness and untamed areas. This led to sacrifice in order for safe travel into these areas.

The later Roman version of this deity is as the goddess Trivia, "the three ways." Eligius in the seventh century reminded his recently converted flock in Flanders that "No Christian should make or render any devotion to the gods of the trivium, where three roads meet, to the fanes or the rocks, or springs or groves or corners," worship practices that had been common in his Celtic congregation.[14]

Over time, the apotropaic associations with the goddess, specifically with respect to her role in driving away evil spirits, led to the belief that Hecate, if offended, could summon evil spirits. Thus, invocations to Hecate arose which characterized her as the governess of the borders between the mortal world and the spirit world [15].

Goddess of magic, sorcery and the dead

In the modern imagination, Hecate is most often remembered as a chthonic goddess, associated with sorcery, necromancy and the mysteries of the dead. Indeed, Hecate was the goddess who appeared most often in magical texts such as the Greek Magical Papyri and curse tablets, along with Hermes. The transformation of the figure of Hekate can be traced to fifth-century Athens, as in two fragments of Aeschylus (ca. 525–456 B.C.E.) she appears as a great goddess, while in Sophocles (495-406 B.C.E.) and Euripides (480–406 B.C.E.) she has already become the mistress of witchcraft and keres.[16] [17]

Eventually, Hecate’s power resembled that of sorcery. Medea, who was a priestess of Hecate, used witchcraft in order to handle magic herbs and poisons with skill, and to be able to stay the course of rivers, or check the paths of the stars and the moon.[18][19][20]

These chthonic associations would developed through a relatively late affiliation with the tale of Persephone's abduction by Hades. Specifically, the Homeric Hymn to Demeter suggests that Hecate was one of the two gods (along with all-seeing Helios) who were witness to the young goddess's kidnapping, and who accompanies Demeter (the grieving mother) in her quest to return her daughter to the world of the living. When the two are finally reunited, they are described given due thanks to the shadowy goddess:

- Then bright-coiffed Hecate came near to them, and often did she embrace the daughter of holy Demeter: and from that time the lady Hecate was minister and companion to Persephone (Homeric Hymn to Demeter, 438-440).[21]

This connection with the world of the dead is even further established by the time of Vergil's composition of the Aeneid, which (in Book 6) describes the hero's visit to the Underworld. When visiting this grim twilight realm, the protagonist is apprised of the various tortures being visited on the souls of the impious and immoral dead, all under the watchful eye of Hecate.[22]

Representations

The earliest depictions of Hecate are single faced, not triplicate. Summarizing the early trends in artistic depictions of the goddess, Lewis Richard Farnell writes:

- The evidence of the monuments as to the character and significance of Hekate is almost as full as that of the literature. But it is only in the later period that they come to express her manifold and mystic nature. Before the fifth century there is little doubt that she was usually represented as of single form like any other divinity, and it was thus that the Boeotian poet ([Hesiod]) imagined her, as nothing in his verses contains any allusion to a triple formed goddess. The earliest known monument is a small terracotta found in Athens, with a dedication to Hekate (Plate XXXVIII. a), in writing of the style of the sixth century. The goddess is seated on a throne with a chaplet bound round her head; she is altogether without attributes and character, and the only value of this work, which is evidently of quite a general type and gets a special reference and name merely from the inscription, is that it proves the single shape to be her earlier from, and her recognition at Athens to be earlier than the Persian invasion.[23]

The second-century traveler Pausanias stated that Hecate was first depicted in triplicate by the sculptor Alkamenes in the Greek Classical period of the late fifth century. Some classical portrayals, depict her in this form holding a torch, a key and a serpent. Others continue to depict her in singular form. Hecate's triplicity is represented in the vast frieze of the great Pergamon Altar, which depicts the Titanomachy (the mythic battle between the Olympians and the Titans). In the Argolid, near the shrine of the Dioscuri, Pausanias also tells of a temple of Hecate opposite the sanctuary of Eilethyia: "The image is a work of Scopas. This one is of stone, while the bronze images opposite, also of Hekate, were made respectively by Polycleitus and his brother Naucydes, son of Mothon."[24]

In general, the representations of Hecate seem to follow a similar progression to the development of her cultic and mythic forms, evolving in tandem with the public conception of the goddess. Thus, as her characterization began to assume greater elements of the chthonic and the uncanny, visual representations followed suit.[25]

Cult of Hecate

As mentioned above, and in spite of the ubiquity of popular belief in the goddess, Hecate was not originally a Greek deity. Instead, the roots of her veneration seem to stem from the Carians of Asia Minor.[26] More specifically, her most important sanctuary was Lagina, a theocratic city-state where the goddess was served by eunuchs, and was celebrated through sacrifices and festivals.[27] At this temple, "the goddess was worshipped as sōteira, mēgiste, and epiphanestatē; her exalted rank and function here are unmatched in cults of Hecate elsewhere"[28] [29] Moreover, this influence was such that she was also seen as the patroness of nearby Stratonikea.[30] ; [31] The case for Hecate's origin's in Anatolia is bolstered by the fact that this is the only region where theophoric names incorporating "Hecate" are attested.[32]

This type of organized temple observance is attested to in Hesiod's Theogony:

- For to this day, whenever any one of men on earth offers rich sacrifices and prays for favor according to custom, he calls upon Hecate. Great honor comes full easily to him whose prayers the goddess receives favorably, and she bestows wealth upon him; for the power surely is with her (404-452).[33]

In Thrace, on the other hand, she played a role similar to that of lesser-Hermes, namely a governess of liminal points and the wilderness, bearing little resemblance to the night-walking crone that she became.

As her cult spread into other areas of Greece,[34] it led to a theological conflict, as Hecate’s role was already filled by other more prominent gods in the Greek pantheon, above all by Artemis, and by more archaic figures, such as Nemesis. It was likely at this time that her associations with death and magic developed, as these were domains that were relatively under-represented in the Olympic Pantheon.

In this role, Hecate was seen as able to use her chthonic powers to deliver spiritual punishment to moral wrong-doers. Using "curse tablets," which were buried in the ground, supplicants requested the aid of the goddess in pursuing their interpersonal vendettas, many of which have subsequently been discovered through archaeological research. One example has been found that references a legal battle with an individual named Phrerenicus:

- Let Pherenicus be bound before Hermes Chthonios and Hecate Chthonia. … And just as the lead is held in no esteem and is cold, so may Pherenicus and his things be held in no esteem and be cold, and so for the things which Pherenicus' collaborators say and plot concerning me.[35] [36]

Further, this association with evil spirits led to an increase in her worship at the household level. For instance, one practice (poetically described as the banquet of Hekate) referred to "offerings made … to the mistress of spirits, in order to avert evil phantoms from the house. None of the household would touch the food."[37] To this end, worshipers fearing the taint of evil or contagion would occasionally sacrifice a dog at the crossroads, also meaning to placate the "mistress of ghosts."[38]

Festivals

Hecate was worshiped by both the Greeks and the Romans who had their own festivals dedicated to her. According to Ruickbie, the Greeks observed two days sacred to Hecate, one on the 13th of August and one on the 30th of November, whilst the Romans observed the 29th of every month as her sacred day.[39] Further, the household observances (described above) always took place on the "thirtieth day [of the month], which was sacred to the dead."[40]

Cross-cultural parallels

The figure of Hecate can often be associated with the figure of Isis in Egyptian myth, mainly due to her relationship with esoteric knowledge. In Hebrew myth, she is often compared to the figure of Lilith and to the Whore of Babylon, in later Christian tradition. Both were symbols of liminal points, with Lilith also playing a role in sorcery. She is also comparable to Hel of Nordic myth in her underworld function.

Before she became associated with Greek mythology, she had many similarities with Artemis (wilderness, and watching over wedding ceremonies) and Hera (child rearing and the protection of young men or heroes, and watching over wedding ceremonies).

Epithets

- Chthonian (Earth/Underworld goddess)

- Enodia (Goddess of the paths)

- Antania (Enemy of mankind)

- Artemis of the crossroads

- Phosphoros (the light-bringer)

- Soteira ("Savior")

- Trioditis (Gr.)

- Trivia (Latin: Goddess of Three Roads)

- Klêidouchos (Keeper of the Keys)

- Tricephalus or Triceps (The Three-Headed)[41]

Notes

- ↑ Walter Burkert, Greek Religion: Archaic and Classical. (Oxford, UK: Blackwell. 1987), 171

- ↑ Theodor Kraus. Hekate: Studien zu Wesen u. Bilde der Göttin in Kleinasien u. Griechenland. (Heidelberg, 1960), 12.

- ↑ H. J. Rose. A Handbook of Greek Mythology. (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1959), 121-122.

- ↑ Sarah Iles Johnston. Restless Dead: Encounters Between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece. (1991)

- ↑ William Berg, "Hecate: Greek or 'Anatolian'?" Numen 21 (Fasc. 2) (August 1974): 129, 139.

- ↑ Johnston (1991)

- ↑ Gantz, 26.

- ↑ These associations were especially prominent in rural areas. See: Jon D. Mikalson. Ancient Greek Religion. (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2005), 215, 217.

- ↑ Johnston (1991)

- ↑ Rose (1959)

- ↑ Lewis Richard Farnell. The Cults of the Greek States, (Vol. 2), (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1907), 508-509, 515-519, also comment on the relationship between the two deities.

- ↑ Rose, 121-122

- ↑ Martin Puhvel, "The Mystery of the Cross-Roads," Folklore 87(2) (1976): 175.

- ↑ See the Vita of Saint Eligius at northvegr.org. Retrieved June 23, 2007.

- ↑ Johnston (1991)

- ↑ Gantz, 26-27.

- ↑ Farnell (Vol. II), 510-513.

- ↑ See: Euripides, Medea

- ↑ Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica

- ↑ Apollodorus, The Library.

- ↑ Homer. Homeric Hymn to Demeter. accessed online at sacred-texts.com. Retrieved June 23, 2007.

- ↑ Barry B. Powell. Classical Myth, Second Edition. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1998), 300, 301

- ↑ Lewis Richard Farnell, "Hecate in Art," The Cults of the Greek States. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1896).

- ↑ Pausanius, Description of Greece ii.22.7, W. H. S. Jones translation accessible online at theoi.com. Retrieved June 23, 2007. See also: Gantz, 27.

- ↑ For an excellent overview of the evolution of Hecate in sculpture, see Charles M. Edwards, "The Running Maiden from Eleusis and the Early Classical Image of Hekate," American Journal of Archaeology 90(3), (July 1986): 307-318.

- ↑ Kraus (1960)

- ↑ Burkert

- ↑ Berg, 128

- ↑ See also: Kraus, 12.

- ↑ Strabo, Geography (xiv.2.25)

- ↑ Kraus (1960)

- ↑ See: Kraus, (1960) as he offers the first comprehensive modern discussion of Hecate in monuments and material culture.

- ↑ Hesiod, Theogony, accessed online at sacred-texts.com. Retrieved June 23, 2007.

- ↑ See theoi.com for an excellent overview of the various classical texts that mention the worship of the goddess (in its various forms).

- ↑ Quoted in Price, 101-102.

- ↑ See also: Mikalson, 38.

- ↑ Farnell (Vol. II), 511.

- ↑ Farnell (Vol. II), 515.

- ↑ Leo Ruickbie. Witchcraft Out of the Shadows: A Complete History. (London, UK: Robert Hale, 2004), 19.

- ↑ Farnell (Vol. II), 511.

- ↑ For an excellent listing of poetic and cultic epithets, see theoi.com. Retrieved June 23, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Apollodorus. Gods & Heroes of the Greeks, Translated and with an Introduction and Notes by Michael Simpson. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1977. ISBN 0870232053.

- Burkert, Walter. Greek Religion: Archaic and Classical, Translated by John Raffan. Oxford: Blackwell, 1985. ISBN 0631112413.

- Berg, William. "Hecate: Greek or 'Anatolian'?" Numen 21 (Fasc. 2) (August 1974): 128-140.

- Dillon, Matthew. Pilgrims and Pilgrimage in Ancient Greece. London; New York: Routledge, 1997. ISBN 0415127750.

- Edwards, Charles M. "The Running Maiden from Eleusis and the Early Classical Image of Hekate." American Journal of Archaeology 90(3) (July 1986): 307-318.

- Farnell, Lewis Richard. The Cults of the Greek States. (in Five Volumes). Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1907.

- __________. "Hecate in Art," The Cults of the Greek States. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1896.

- Johnston, Sarah Iles. Hekate Soteira: A Study of Hekate's Role in the Chaldean Oracles and Related Literature. An American Philological Association Book: 1990. ISBN 1555404278

- __________. Restless Dead: Encounters Between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece. University of California Press: 1991. ISBN 0520217071

- Kerenyi, Karl. The Gods of the Greeks. London & New York: Thames and Hudson, 1951. ISBN 0500270481

- Kraus, Theodor. Hekate: Studien zu Wesen u. Bilde der Göttin in Kleinasien u. Griechenland. Heidelberg, 1960. (in German)

- Mikalson, Jon D. Ancient Greek Religion. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2005. ISBN 0631232222.

- Parke, H. W. Festivals of the Athenians. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1977. ISBN 0801410541.

- Powell, Barry B. Classical Myth, Second Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1998. ISBN 0137167148.

- Puhvel, Martin. "The Mystery of the Cross-Roads." Folklore 87(2) (1976): 167-177.

- Rose, H. J. A Handbook of Greek Mythology. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1959. ISBN 0525470417

- Ruickbie, Leo. Witchcraft Out of the Shadows: A Complete History. London, UK: Robert Hale, 2004. ISBN 0709075677

- Salmonson, Jessica Amanda. The Encyclopedia of Amazons. Saint Paul, MN: Paragon House, 1991. ISBN 1557784205

- Vol, Mary. "Athene (Athena) and Artemis." in Seppo Sakari Telenius. Athena-Artemis. Helsinki: Kirja kerrallaan, 2005 and 2006. ISBN 9529205600

- Ventris, Michael and John Chadwick. Documents in Mycenaean Greek, Second Edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1973. ISBN 0521085586..

External links

All links retrieved December 12, 2017.

- Myths of the Greek Goddess Hecate -

- Theoi Project, Hecate classical literary sources and art -

- Hesiod, Theogony, Works and Days. An English translation

- Hekate in Greek esotericism: Ptolemaic and Gnostic transformations of Hecate

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.