Difference between revisions of "Hagfish" - New World Encyclopedia

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 56: | Line 56: | ||

=== Slime === | === Slime === | ||

| − | Extant hagfish are long, [[vermiform]], and can exude copious quantities of a sticky [[slime]] or [[mucus]] (from which the typical species ''Myxine glutinosa'' was named). When captured and held by the tail, | + | Extant hagfish are long, [[vermiform]], and can exude copious quantities of a sticky [[slime]] or [[mucus]] (from which the typical species ''Myxine glutinosa'' was named). There are from 70 to 200 slime glands found in each of two ventrolateral lines from head to tail (Nelson 1994). The slime glands contain both mucous cells and thread cells, with the thread from the thread cells probably adding tensile strength to the slime (Nelson 1994). Indeed, the [[mucus]] excreted by hagfish is unique in that it includes strong, threadlike fibers similar to [[spider silk]], causing the slime to be fiber-reinforced. No other slime secretion known is reinforced with fibers in the same manner as hagfish slime. The fibers are about as fine as spider silk (averaging 2 [[micrometer]]s), but can be 12 centimeters long. When the [[coil]]ed fibers leave the gland, they unravel quickly to their full length without tangling. |

| + | |||

| + | When captured and held by the tail, hagfish escape by secreting the fibrous slime, which turns into a thick and sticky gel when combined with water. They clean off the slime by tying themselves in an [[overhand knot]], which works its way from the head to the tail of the animal, scraping off the slime as it goes. Some authorities conjecture that this singular knotting behavior may assist them in extricating themselves from the jaws of predatory fish. The "sliming" also seems to act as a distraction to predators, and free-swimming hagfish are seen to "slime" when agitated and will later clear the mucus off by way of the same traveling-knot behavior. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Slime appears to be particularly effective at clogging gills of fish and thus it is speculated that sliming may be an effective defense mechanism against fish, which are not among the main hagfish predators (Lim et al. 2006). | ||

An adult hagfish can secrete enough slime to turn a large bucket of water into gel in a matter of minutes. | An adult hagfish can secrete enough slime to turn a large bucket of water into gel in a matter of minutes. | ||

| Line 62: | Line 66: | ||

==Behavior and reproduction== | ==Behavior and reproduction== | ||

| − | Hagfish | + | Hagfish tend to burrow under rocks or in mud, in highly saline waters, and away from bright light (Lee 2002). They are mostly found either near the mouths of rivers or at depths of 25 or more meters, with ''Myxiine circifrons'' found at more than 1000 meters below the ocean surface (Lee 2002). |

| + | |||

| + | Hagfish typically are scavengers, entering decaying and dead [[fish]] and invertebrates (including ([[polychaete]] [[marine worm]]s and shrimp), feeding on the insides. Living organisms also are consumed. While having no ability to enter through [[skin]], they often enter through natural openings such as the [[mouth]], [[gill]]s, or [[anus]] and consume their prey from the inside out. They can be a great nuisance to fishermen, as they are known to infiltrate and devour a catch before it can be pulled to the surface. | ||

Like [[leech]]es, they have a sluggish metabolism and can survive months between feedings. | Like [[leech]]es, they have a sluggish metabolism and can survive months between feedings. | ||

| Line 70: | Line 76: | ||

Hagfish do not have a [[larva]]l stage, in contrast to [[lamprey]]s, which have a long larval phase. | Hagfish do not have a [[larva]]l stage, in contrast to [[lamprey]]s, which have a long larval phase. | ||

| − | == Classification == | + | == Classification and evolution== |

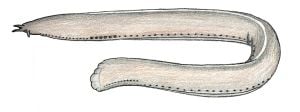

[[Image:Eptatretus cirrhatus (New Zealand hagfish).gif|thumb|right|Drawing of a [[New Zealand hagfish]].]] | [[Image:Eptatretus cirrhatus (New Zealand hagfish).gif|thumb|right|Drawing of a [[New Zealand hagfish]].]] | ||

| − | + | Hagfish appear to have branched off from the chordates before the vertebral column appeared (Lee 2002). A single fossil of hagfish shows that there has been little evolutionary change in the last 300 million years (Marshall 2001). There have been claims that the hagfish eye is significant to the evolution of more complex eyes (UQ 2003). | |

| − | + | There has been long discussion in scientific literature about the hagfish being classified as [[vertebrate]]s versus [[invertebrate]]s. Given their classification as [[Agnatha]], Hagfish are seen as an elementary vertebrate in between [[Prevertebrate]] and [[Gnathostome]]. They tend to be classified either under the subphylum Vertebrata or as an invertebrate within subphylum [[Craniata]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | === Species === |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Image:Eptatretus minor.JPG|thumb|right|Drawing of ''[[eptatretus minor]]'']] | [[Image:Eptatretus minor.JPG|thumb|right|Drawing of ''[[eptatretus minor]]'']] | ||

| − | About 66 species are known, in 7 genera. A number of the species have only been recently discovered, living at depths of several hundred | + | About 66 species are known, in 7 genera. A number of the species have only been recently discovered, living at depths of several hundred meters. Some of the species are listed here: |

* Genus ''[[Eptatretus]]'' | * Genus ''[[Eptatretus]]'' | ||

| Line 166: | Line 147: | ||

** ''[[Quadratus taiwanae]]'' <small>(Shen and Tao, 1975)</small> | ** ''[[Quadratus taiwanae]]'' <small>(Shen and Tao, 1975)</small> | ||

** ''[[Quadratus yangi]]'' | ** ''[[Quadratus yangi]]'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Importance== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hagfish are important in food chains, serving as scavengers, while themselves being consumed by seabirds, pinnipeds, and crustaceans (Lim et al. 2006). Fish, however, are not among their main predators (Lim et al. 2006). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hagfish are consumed in some regions of the world, being particularly important commercially in [[Korea]] (Lee 2002). They also are made into leather items (Lee 2002). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Hagfish also are important in scientific research. They are useful in the study of tumors (Lee 2002), and genetic analysis investigating the relationships among [[chordate]]s. Research is being done regarding potential uses for their slime or a similar synthetic gel including the fibers. Some possibilities include new biodegradable [[polymers]], space-filling gels, or a means of stopping blood flow in accident victims and surgery patients (Vowles 2008). | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

| − | + | ||

* {{cite web | * {{cite web | ||

| url = http://www.bioone.org/perlserv/?request=get-abstract&doi=10.1643%2F0045-8511%282006%296%5B225%3AANSOGS%5D2.0.CO%3B2 | | url = http://www.bioone.org/perlserv/?request=get-abstract&doi=10.1643%2F0045-8511%282006%296%5B225%3AANSOGS%5D2.0.CO%3B2 | ||

| Line 210: | Line 200: | ||

* Lee, J. 2002. [http://www.jyi.org/volumes/volume5/issue7/features/lee.html Hagfish aren't so horrible after all]. ''Journal of Young Investigators'' 5(7). (Undergraduate, but peer-reviewed science journal). Retrieved June 1, 2008. | * Lee, J. 2002. [http://www.jyi.org/volumes/volume5/issue7/features/lee.html Hagfish aren't so horrible after all]. ''Journal of Young Investigators'' 5(7). (Undergraduate, but peer-reviewed science journal). Retrieved June 1, 2008. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Marshall, P. M. 2001. [http://www.networksplus.net/maxmush/myxinidae.html Myxinidae information]. ''Mudminnow Information Services''. Retrieved June 1, 2008. | ||

| + | |||

* Nelson, J. S. 1994. ''Fishes of the World'', 3rd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0471547131. | * Nelson, J. S. 1994. ''Fishes of the World'', 3rd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0471547131. | ||

| Line 217: | Line 210: | ||

* Ressem, S. 2003. [http://www.ntnu.no/gemini/2003-06e/26-27.htm Slimy, disgusting and useful]. ''Norwegian University of Science and Technology''. Retrieved May 31, 2008. | * Ressem, S. 2003. [http://www.ntnu.no/gemini/2003-06e/26-27.htm Slimy, disgusting and useful]. ''Norwegian University of Science and Technology''. Retrieved May 31, 2008. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * University of Queensland (UQ). 2003. [http://www.physorg.com/news115919015.html Keeping an eye on evolution]. ''PhysOrg.com''. Retrieved June 1, 2008. | ||

| + | |||

| + | .<ref>{{cite web | ||

| + | |url=http://www.uoguelph.ca/atguelph/05-11-09/featuresslime.shtml | ||

| + | |title=From Slime to 'Bio-Steel' | ||

| + | |last=Vowles | ||

| + | |first=Andrew | ||

| + | |publisher=University of Guelph | ||

| + | |accessdate=2008-02-19 | ||

| + | }}</ref> | ||

* Frank, T. 2004. [http://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/explorations/04deepscope/logs/aug9/aug9.html Disgusting hagfish and magnificent sharks]. ''NOAA Ocean Explorer''. Retrieved May 31, 2008. | * Frank, T. 2004. [http://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/explorations/04deepscope/logs/aug9/aug9.html Disgusting hagfish and magnificent sharks]. ''NOAA Ocean Explorer''. Retrieved May 31, 2008. | ||

| − | + | First published online January 31, 2006 | |

| + | Journal of Experimental Biology 209, 702-710 (2006) | ||

| + | Published by The Company of Biologists 2006 | ||

| + | http://jeb.biologists.org/cgi/content/full/209/4/702 | ||

| + | Hagfish slime ecomechanics: testing the gill-clogging hypothesis | ||

| − | + | Jeanette Lim, Douglas S. Fudge*, Nimrod Levy and John M. Gosline | |

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:Life sciences]] | [[Category:Life sciences]] | ||

Revision as of 15:36, 1 June 2008

| Hagfish | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Pacific hagfish resting on bottom

280 m depth off Oregon coast | ||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

|

Eptatretus |

Hagfish is the common name for the marine craniates comprising the family Myxinidae of the order Myxiniformes (Hyperotreti) of the class (or subphylum) Myxini, characterized by a scaleless, eel-like body, without paired fins, and without a vertebrae, but having a cranium. The Myxinidae is the only family in Myxiniformes, which is the only order in the class Myxini, and thus hagfish is variously used for any of the three taxonomic levels (ITIS 2003; Nelson 1994). Hagfish has traditionally been considered part of the superclass Agnatha within the sub-phylum Vertebrata, but the lack of a vertebrae has led some to place it outside of the Vertebrata, and thus also to not consider hagfish to be a fish. Hagfish are the only animals that have a skull but not a vertebral column.

Although hagfish have an ancient history, possibly tracing back 300 million years ago to the Carboniferous, there remain extant hagfish. These animals, which are characterized by degenerate eyes, barbels present around the mouth, and teeth only on the tongue, are found in marine environments and are scavengers that mostly eat the insides of dying or dead fish and invertebrates (Nelson 1994). The extant Myxinidae are unique in being the only vertebrate in which the body fluids are isomotic with seawater (Nelson 1994).

Although hagfish are sometimes called "slime eels," they are not eels at all, which are part of the bony fish.

While a staple food in Korea, the unusual feeding habits and slime-producing capabilities of hagfish have led members of the scientific and popular media to dub the hagfish as the most "disgusting" of all sea creatures (URI 2002; Ressem 2003; Frank 2004). Nonetheless, they provide important values ***

Overview

Hagfish are jawless and generally classified with the lampreys into the superclass Agnatha (jawless vertebrates) within the subphylum Vertebrata. However, hagfish actually lack vertebrae. For this reason, they sometimes are separated from the vertebrates. Janvier (1981) and a number of others put hagfish in the subphylum Myxini, which along with the subphylum Vertebrata comprises the taxon Craniata, recognizing the common possession of a cranium (Janvier 1981). Others, however, use the terms Vertebrata and Craniata as synonyms, rather than different levels of classification, and retain the use of Agnatha and hagfish (Myxini) as within the vertebrates (Nelson 1994). The other living member of Agnatha, the lamprey, has primitive vertebrae made of cartilage.

While some place Myxini as a subphylum equal to the subphylum Vertebrata (Janvier 1981), others place Myxini as a class, whether within the subphylum Vertebrata (ITIS 2003) or outside as the only class in the clade Craniata that does not also belong to the subphylum Vertebrata (Campbell and Reece 2005).

As members of Agnatha (Greek, "no jaws"), hagfish are characterized by the absence of jaws derived from gill arches, although they do have a biting apparatus that is not considered to have been derived from gill arches (Nelson 1994). Other common characteristics of Agnatha include the absence of paired fins, absence of pelvic fins, the presence of a notochord both in larvae and adults, and seven or more paired gill pouches. In addition, the gills open to the surface through pores rather than slits, and the gill arch skeleton is fused with neurocranium (Nelson 1994).

Despite their name, there is some debate about whether hagfish are strictly fish , since they belong to a much more primitive lineage than any other group that is commonly defined fish (Chondrichthyes and Osteichthyes), and because of the lack of a vertebrae commonly associated with the definition of fish. However, many authors do place hagfish as a primitive fish.

Description

Extant hagfish are placed in the family Myxinidae within the order Myxiniformes (Hyperotreti) and subphylum or class Myxini.

Members of the order Myxiniformes are characterized by one semicircular canal, absence of eye musculature, a single olfactory capsule with few folds in sensory epithelium, no bone, and 1 to 16 pairs of external gill openings (Nelson 1994).

Members of the family Myxinidae are characterized by the lack of a dorsal fin, barbels present around the mouth, degenerate eyes, teeth only on the tongue, no metamorphosis, and ovaries and testes in the same individual but only one functional gonad (Nelson 1994). Note that many of these features differ from the other agnathan, lampreys, which have one or two dorsal fins, well-developed eyes, absence of barbels, separate sexes, a larval stage that undergoes radical metamorphosis, and teeth bothon the oral disc and tongue (Nelson 1994).

Hagfish have a scaleless, elongated, eel-like body without paired fins. The extant hagfish average about half a meter (18 inches) long. The largest known species is Eptatretus goliath with a specimen recorded at 127 centimeters, while Myxine kuoi and Myxine pequenoi seem to reach no more than 18 centimeters.

Extant hagfish have paddle-like tails, cartilaginous skulls, and tooth-like structures composed of keratin. Colors depend on the species, ranging from pink to blue-gray, and may have black or white spots. Eyes may be vestigial or absent. Hagfish have no true fins and have six barbels around the mouth and a single nostril. Instead of vertically articulating jaws like Gnathostomata (vertebrates with jaws), they have a pair of horizontally moving structures with tooth-like projections for pulling off food.

The circulatory systems of the extant hagfish have both closed and open blood vessels, with a heart system that is more primitive than that of vertebrates, bearing some resemblance to that of some worms. This system comprises a "brachial heart", which functions as the main pump, and three types of accessory hearts: the "portal" heart(s), which carry blood from intestines to liver; the "cardinal" heart(s), which move blood from the head to the body; and the "caudal" heart(s), which pump blood from the trunk and kidneys to the body. None of these hearts are innervated, so their function is probably modulated, if at all, by hormones.

Slime

Extant hagfish are long, vermiform, and can exude copious quantities of a sticky slime or mucus (from which the typical species Myxine glutinosa was named). There are from 70 to 200 slime glands found in each of two ventrolateral lines from head to tail (Nelson 1994). The slime glands contain both mucous cells and thread cells, with the thread from the thread cells probably adding tensile strength to the slime (Nelson 1994). Indeed, the mucus excreted by hagfish is unique in that it includes strong, threadlike fibers similar to spider silk, causing the slime to be fiber-reinforced. No other slime secretion known is reinforced with fibers in the same manner as hagfish slime. The fibers are about as fine as spider silk (averaging 2 micrometers), but can be 12 centimeters long. When the coiled fibers leave the gland, they unravel quickly to their full length without tangling.

When captured and held by the tail, hagfish escape by secreting the fibrous slime, which turns into a thick and sticky gel when combined with water. They clean off the slime by tying themselves in an overhand knot, which works its way from the head to the tail of the animal, scraping off the slime as it goes. Some authorities conjecture that this singular knotting behavior may assist them in extricating themselves from the jaws of predatory fish. The "sliming" also seems to act as a distraction to predators, and free-swimming hagfish are seen to "slime" when agitated and will later clear the mucus off by way of the same traveling-knot behavior.

Slime appears to be particularly effective at clogging gills of fish and thus it is speculated that sliming may be an effective defense mechanism against fish, which are not among the main hagfish predators (Lim et al. 2006).

An adult hagfish can secrete enough slime to turn a large bucket of water into gel in a matter of minutes.

Behavior and reproduction

Hagfish tend to burrow under rocks or in mud, in highly saline waters, and away from bright light (Lee 2002). They are mostly found either near the mouths of rivers or at depths of 25 or more meters, with Myxiine circifrons found at more than 1000 meters below the ocean surface (Lee 2002).

Hagfish typically are scavengers, entering decaying and dead fish and invertebrates (including (polychaete marine worms and shrimp), feeding on the insides. Living organisms also are consumed. While having no ability to enter through skin, they often enter through natural openings such as the mouth, gills, or anus and consume their prey from the inside out. They can be a great nuisance to fishermen, as they are known to infiltrate and devour a catch before it can be pulled to the surface.

Like leeches, they have a sluggish metabolism and can survive months between feedings.

Very little is known about hagfish reproduction. In some species, sex ratio can be as high as 100 to 1 in favor of females. In other species, individual hagfish that are hermaphroditic are not uncommon. These individuals have both ovaries and testes, but the female gonads remain non-functional until the individual has reached a particular stage in the hagfish lifecycle. Females typically lay 20 to 30 yolky eggs that tend to aggregate due to having Velcro-like tufts at either end.

Hagfish do not have a larval stage, in contrast to lampreys, which have a long larval phase.

Classification and evolution

Hagfish appear to have branched off from the chordates before the vertebral column appeared (Lee 2002). A single fossil of hagfish shows that there has been little evolutionary change in the last 300 million years (Marshall 2001). There have been claims that the hagfish eye is significant to the evolution of more complex eyes (UQ 2003).

There has been long discussion in scientific literature about the hagfish being classified as vertebrates versus invertebrates. Given their classification as Agnatha, Hagfish are seen as an elementary vertebrate in between Prevertebrate and Gnathostome. They tend to be classified either under the subphylum Vertebrata or as an invertebrate within subphylum Craniata.

Species

About 66 species are known, in 7 genera. A number of the species have only been recently discovered, living at depths of several hundred meters. Some of the species are listed here:

- Genus Eptatretus

- Inshore hagfish, Eptatretus burgeri (Girard, 1855)

- New Zealand hagfish, Eptatretus cirrhatus (Forster, 1801)

- Black hagfish, Eptatretus deani (Evermann & Goldsborough, 1907)

- Guadalupe hagfish, Eptatretus fritzi Wisner & McMillan, 1990

- Eptatretus goliath Mincarone & Stewart, 2006

- Sixgill hagfish, Eptatretus hexatrema (Müller, 1836)

- Eptatretus lopheliae Fernholm & Quattrini, 2008

- Shorthead hagfish, Eptatretus mcconnaugheyi Wisner & McMillan, 1990

- Eptatretus mendozai Hensley, 1985

- Eightgill hagfish, Eptatretus octatrema (Barnard, 1923)

- Fourteen-gill hagfish, Eptatretus polytrema (Girard, 1855)

- Fivegill hagfish, Eptatretus profundus (Barnard, 1923)

- Cortez hagfish, Eptatretus sinus Wisner & McMillan, 1990

- Gulf hagfish, Eptatretus springeri (Bigelow & Schroeder, 1952)

- Pacific hagfish, Eptatretus stoutii (Lockington, 1878)

- Eptatretus strickrotti Møller & Jones, 2007

- Genus Myxine

- Patagonian hagfish Myxine affinis Günther, 1870

- Myxine australis Jenyns, 1842

- Cape hagfish, Myxine capensis

- Whiteface hagfish, Myxine circifrons Garman, 1899

- Myxine debueni Wisner & McMillan, 1995

- Myxine dorsum Wisner & McMillan, 1995

- Myxine fernholmi Wisner & McMillan, 1995

- Myxine formosana Mok & Kuo, 2001

- Myxine garmani Jordan & Snyder, 1901

- Hagfish (or Atlantic hagfish), Myxine glutinosa

- Myxine hubbsi Wisner & McMillan, 1995

- Myxine hubbsoides Wisner & McMillan, 1995

- White-headed hagfish, Myxine ios

- Myxine jespersenae Møller, Feld, Poulsen, Thomsen & Thormar, 2005

- Myxine knappi Wisner & McMillan, 1995

- Myxine kuoi Mok, 2002

- Myxine limosa Girard, 1859

- Myxine mccoskeri Wisner & McMillan, 1995

- Myxine mcmillanae Hensley, 1991

- Myxine paucidens Regan, 1913

- Myxine pequenoi Wisner & McMillan, 1995

- Myxine robinsorum Wisner & McMillan, 1995

- Myxine sotoi Mincarone, 2001

- Genus Nemamyxine

- Nemamyxine elongata Richardson, 1958

- Nemamyxine kreffti McMillan and Wisner, 1982

- Genus Neomyxine

- Neomyxine biniplicata (Richardson and Jowett, 1951)

- Genus Notomyxine

- Notomyxine tridentiger (Garman, 1899)

- Genus Paramyxine

- Paramyxine atami Dean, 1904

- Paramyxine cheni Shen and Tao, 1975

- Paramyxine fernholmi Kuo, Huang and Mok, 1994

- Paramyxine sheni Kuo, Huang and Mok, 1994

- Paramyxine wisneri Kuo, Huang and Mok, 1994

- Genus Quadratus

- Quadratus ancon Mok, Saavedra-Diaz and Acero P., 2001

- Quadratus nelsoni (Kuo, Huang and Mok, 1994)

- Quadratus taiwanae (Shen and Tao, 1975)

- Quadratus yangi

Importance

Hagfish are important in food chains, serving as scavengers, while themselves being consumed by seabirds, pinnipeds, and crustaceans (Lim et al. 2006). Fish, however, are not among their main predators (Lim et al. 2006).

Hagfish are consumed in some regions of the world, being particularly important commercially in Korea (Lee 2002). They also are made into leather items (Lee 2002).

Hagfish also are important in scientific research. They are useful in the study of tumors (Lee 2002), and genetic analysis investigating the relationships among chordates. Research is being done regarding potential uses for their slime or a similar synthetic gel including the fibers. Some possibilities include new biodegradable polymers, space-filling gels, or a means of stopping blood flow in accident victims and surgery patients (Vowles 2008).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- New species Eptatretus goliath. BIOONE Online Journals. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- J.M. Jørgensen, J.P. Lomholt, R.E. Weber and H. Malte (eds.) (1997). The biology of hagfishes. London: Chapman & Hall.

- Delarbre et al (2002). Complete Mitochondrial DNA of the Hagfish, Eptatretus burgeri: The Comparative Analysis of Mitochondrial DNA Sequences Strongly Supports the Cyclostome Monophyly. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 22 (2): 184–192.

- Bondareva and Schmidt (2003). Early Vertebrate Evolution of the TATA-Binding Protein, TBP. Molecular Biology and Evolution 20 (11): 1932–1939.

- Hardisty, M. W., and I. C. Potter. The Biology of lampreys.??

.[1]

- Fudge, D. (2001). Hagfishes: Champions of Slime Nature Australia, Spring 2001 ed., Australian Museum Trust, Sydney. pp. 61–69.

- Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS). 2003. Agnatha ITIS Taxonomic Serial No.: 159693. Retrieved May 31, 2008.

- Janvier, P. 1981. The phylogeny of the Craniata, with particular reference to the significance of fossil "agnathans." J. Vertebr. Paleont. 1(2):121-159.

- Lee, J. 2002. Hagfish aren't so horrible after all. Journal of Young Investigators 5(7). (Undergraduate, but peer-reviewed science journal). Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- Marshall, P. M. 2001. Myxinidae information. Mudminnow Information Services. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- Nelson, J. S. 1994. Fishes of the World, 3rd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0471547131.

- University of Rhode Island (URI), Department of Communications. 2002. [http://www.uri.edu/news/releases/html/02-0325-01.html Friends of Oceanography Public Lecture Series

explores the strange, wondrous, and disgusting hagfish]. University of Rhode Island marcy 25, 2002. Retrieved May 31, 2008.

- Ressem, S. 2003. Slimy, disgusting and useful. Norwegian University of Science and Technology. Retrieved May 31, 2008.

- University of Queensland (UQ). 2003. Keeping an eye on evolution. PhysOrg.com. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

.[2]

- Frank, T. 2004. Disgusting hagfish and magnificent sharks. NOAA Ocean Explorer. Retrieved May 31, 2008.

First published online January 31, 2006 Journal of Experimental Biology 209, 702-710 (2006) Published by The Company of Biologists 2006 http://jeb.biologists.org/cgi/content/full/209/4/702 Hagfish slime ecomechanics: testing the gill-clogging hypothesis

Jeanette Lim, Douglas S. Fudge*, Nimrod Levy and John M. Gosline

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ N. A. Campbell and J. B. Reece (2005). Biology Seventh Edition. Benjamin Cummings, San Francisco CA.

- ↑ Vowles, Andrew. From Slime to 'Bio-Steel'. University of Guelph. Retrieved 2008-02-19.