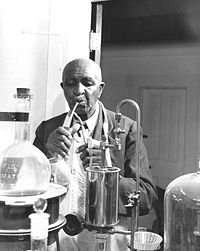

George Washington Carver

George Washington Carver (c. early 1864 – January 5, 1943) was an African American botanist who worked in agricultural extension at the Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, Alabama, and who taught former slaves farming techniques for self-sufficiency. He is also widely credited in American public schools and elsewhere for inventing hundreds of uses for the peanut and other plants, although this laudation amounts to an urban legend. (See Reputed inventions.)

Early years

He was born into slavery in Newton County, Marion Township, near Diamond Grove, now known as Diamond, Missouri. The exact date of birth is unknown due to the haphazard record keeping by slave owners but "it seems likely that he was born in the spring of 1864" [1]. His owner, Moses Carver, was a German American immigrant who had purchased George's mother, Mary, from William P. McGinnis on October 9, 1855 for seven hundred dollars. The identity of Carver's father is unknown but he believed his father was from a neighboring farm and died "shortly after Carver's birth...in a log-hauling accident" [2]. George had three sisters and a brother, all of whom died prematurely. When George was an infant, he, a sister, and his mother were kidnapped by Confederate night raiders and sold in Arkansas, a common practice. Moses Carver hired John Bentley to find them. Only Carver was found, orphaned and near death from whooping cough. Carver's mother and sister had already died, although some reports stated that his mother and sister had gone north with the soldiers. For returning George, Moses Carver rewarded Bentley with his best filly that would later produce winning race horses. This episode caused George a bout of respiratory disease that left him with a permanently weakened constitution. Because of this, he was unable to work as a hand and spent his time wandering the fields, drawn to the varieties of wild plants. He became so knowledgeable that he was known by Moses Carver's neighbors as the "Plant Doctor".

One day he was called to a neighbor's house to help with a plant in need. When he had fixed the problem, he was told to go into the kitchen to collect his reward. When he entered the kitchen, he saw no one. He did, however, see something that changed his life: beautiful paintings of flowers on the walls of the room. From that moment on, he knew that he was going to be an artist as well as a botanist.

After slavery was abolished, Moses and his wife Susan raised George and his brother Jim as their own. They encouraged Carver to continue his intellectual pursuits. "Aunt" Susan taught George the basics of reading and writing.

Since blacks were not allowed at the school in Diamond Grove and he had received news that there was a school for blacks ten miles south in Neosho, he resolved to go there at once. To his dismay, when he reached the town, the school had been closed for the night. As he had nowhere to stay, he slept in a nearby barn. By his own account, the next morning he met a kind woman, Mariah Watkins, from whom he wished to rent a room. When he identified himself "Carver's George," as he had done his whole life, she replied that from now on, his name was "George Carver." George liked this lady very much and her words "You must learn all you can, then go back out into the world and give your learning back to the people," had a great impression on him.

At the age of thirteen, due to his desire to attend high school, he relocated to the home of another foster family in Fort Scott, Kansas. After witnessing the beating to death of a black man at the hands of a group of white men, George left Fort Scott. He subsequently attended a series of schools before earning his diploma at Minneapolis High School in Minneapolis, Kansas.

After high school, George started a laundry business in Olathe, Kansas.

College

Over the next few years, he sent letters to several colleges and was finally accepted at Highland College in Highland, Kansas. He travelled to the college, but he was rejected when they discovered that he was black.

Carver's travels took him to Winterset, Iowa in the mid-1880s, where he met the Milhollands, a white couple who he later credited with encouraging him to pursue higher education. The Milhollands urged Carver to enroll in nearby Simpson College in Indianola, Iowa, which he did, despite his reluctance due to his Highland College rejection.

In 1887, he was accepted into Simpson as its first African-American student. He transferred in 1891 to Iowa State University (then Iowa State Agricultural College), where he was the first black student, and later the first black faculty member.

In order to avoid confusion with another George Carver in his classes, he began to use the name George Washington Carver.

While in college at Simpson, he showed a strong aptitude for singing and art. His art teacher, Etta Budd, was the daughter of the head of the department of horticulture at Iowa State: Joseph Budd. Etta convinced Carver to pursue a career that paid better than art and so he transferred to Iowa State.

At the end of his undergraduate career in 1894, recognizing Carver's potential, Joseph Budd and Louis Pammel convinced Carver to stay at Iowa State for his master's degree. Carver then performed research at the Iowa Agriculture and Home Economics Experiment Station under Pammel from 1894 to his graduation in 1896. It is his work at the experiment station in plant pathology and mycology that first gained him national recognition and respect as a botanist.

The encouragement Etta Budd gave Carver to seek a better-paying career was well warranted, at least for Etta, since she died a poor retired art teacher in a Boone, Iowa retirement home.

Rise to fame

In 1896, he was recruited to Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute (today: Tuskegee University) by Booker T. Washington in Tuskegee, Alabama. He remained there for 47 years until his death in 1943.

Taking an interest in the plight of poor Southern farmers working with soil depleted by repeated crops of cotton, Carver was one of many agricultural workers who advocated employing the well-known practice of crop rotation by alternating cotton crops with other plants, such as legumes (peanuts, cowpeas), or sweet potato to restore nitrogen to the soil. Thus, the cotton crop was improved and alternative cash crops added. He developed an agricultural extension system in Alabama — based on that created at Iowa State University — to train farmers in raising these crops and an industrial research laboratory to develop uses for them.

Carver compiled lists of recipes and products, some of which were original, for these crops in order to popularize their use. His peanut applications included glue, printer's ink, dyes, punches, varnishing cream, soap, rubbing oils, and cooking sauces. He made similar investigations into uses for sweet potato, cowpea and pecan. There is no documented connection between these recipes and any practical commercial products; nonetheless, he was to become famous as an inventor partly on the basis of these recipes. For example, Carver was not involved in the development of modern peanut butter, although he is often credited with this invention [10]. (See Reputed inventions below.)

Until 1915, Carver was not widely known for his agricultural research. However, he became one of the best-known African-Americans of his era when he was praised by Theodore Roosevelt. In 1916, he was made a member of the Royal Society of Arts in England, one of only a handful of Americans at that time to receive this honor. By 1920 with the growth of the peanut market in the U.S., the market was flooded with peanuts from China. That year, southern farmers came together to plead their cause before a Congressional committee hearings on the tariff. Carver was elected, without hesitation, to speak at the hearings. On arrival, Carver was mocked by surprised southern farmers, but he was not deterred and began to explain some of the many uses for the peanut. Initially given ten minutes to present, the now spellbound committee extended his time again and again. The committee rose in applause as he finished his presentation. The Fordney-McCumber Tariff of 1922 included a tariff on imported peanuts.

Carver's presentation to Congress made him famous. He was particularly successful, then and later, because of his natural amiability, showmanship, and courtesy to all audiences, regardless of race and politics. In this period, the American public showed a great enthusiasm for inventors such as Thomas Edison, and it was delighted to see an African-American expert such as Carver. Carver did not claim credit for the uses of the peanut that he presented, but this fact was considered secondary and was partly forgotten. In later years, Carver tried to live the myth that was created around him, for example, by attempting to commercialize three formulas for cosmetics and paints.

Business leaders came to seek Carver's help and he often responded with free advice. Three American presidents — Theodore Roosevelt, Calvin Coolidge and Franklin Roosevelt — met with Carver. The Crown Prince of Sweden studied with him for three weeks. Carver's best known guest was Henry Ford who built a laboratory for Carver. In 1942, the two men denied that they were working together on a solution to the wartime rubber shortage. Carver also did extensive work with soy, which he and Ford considered as an alternative fuel.

In 1923, Carver received the Spingarn Medal from the NAACP, awarded annually for outstanding achievement. In 1928, Simpson College bestowed Carver with an honorary doctorate. In 1940, Carver established the George Washington Carver Foundation at Tuskegee University. In 1941, the George Washington Carver Museum was dedicated at the Tuskegee Institute. In 1942, Carver received the Roosevelt Medal for Outstanding Contribution to Southern Agriculture.

Death and Afterwards

Upon returning home one day, Carver took a bad fall down a flight of stairs; he was found unconscious by a maid who took him to a hospital. Carver died January 5, 1943 at the age of 79 from complications (anemia) resulting from this fall.

On his grave was written the simplest and most meaningful summary of his life. He could have added fortune to fame, but caring for neither, he found happiness and honor in being helpful to the world.

On July 14 1943 [3], President Franklin Delano Roosevelt dedicated $30,000 for the George Washington Carver National Monument west-southwest of Diamond, Missouri - an area where Carver had spent time in his childhood. This dedication marks the first national monument dedicated to an African-American. At this 210-acre national monument, there is a bust of Carver, a ¾-mile nature trail, a museum, the 1881 Moses Carver house, and the Carver cemetery.

Carver appeared on U.S. commemorative stamps in 1948 and 1998, and was depicted on a commemorative half-dollar coin from 1951 to 1954. The USS George Washington Carver (SSBN-656) is also named in his honor.

In 1977, Carver was elected to the Hall of Fame for Great Americans. In 1990, Carver was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. Iowa State University awarded Carver the Doctor of Humane Letters in 1994. On February 15, 2005, an episode of Modern Marvels included scenes from within Iowa State University's Food Sciences Building and about Carver's work. Many institutions honor George Washington Carver to this day, particularly the American public school system. Dozens of elementary schools and high schools are named after him.

George Washington Carver never married.

Reputed inventions

George Washington Carver reputedly discovered three hundred uses for peanuts and hundreds more uses for soybeans, pecans and sweet potatoes. Among the listed items that he suggested to southern farmers to help them economically were his recipes and improvements to/for: adhesives, axle grease, bleach, buttermilk, chili sauce, fuel briquettes, ink, instant coffee, linoleum, mayonnaise, meat tenderizer, metal polish, paper, plastic, pavement, shaving cream, shoe polish, synthetic rubber, talcum powder and wood stain. Three patents (one for cosmetics, and two for paints and stains) were issued to George Washington Carver in the years 1925 to 1927; however, they were not commercially successful in the end. Aside from these patents and some recipes for food, he left no formulas or procedures for making his products[4]. He did not keep a laboratory notebook.

Carver's fame today is typically summarized by the claim that he invented more than 300 uses for the peanut. However, Carver's lists contain many products he did not invent; the lists also have many redundancies. The 105 recipes in Carver's 1916 bulletin [5] were common kitchen recipes, but some appear on lists of his peanut inventions, including salted peanuts, bar candy, chocolate coated peanuts, peanut chocolate fudge, peanut wafers and peanut brittle. Carver acknowledged over two dozen other publications as the sources of the 105 peanut recipes[6]. Carver's list of peanut inventions includes 30 cloth dyes, 19 leather dyes, 18 insulating boards, 17 wood stains, 11 wall boards and 11 peanut flours[7]. These six products alone account for 100 "uses".

Recipe number 51 on the list of 105 peanut uses describes a "peanut butter" that led to the belief that Carver invented the modern product with this name. It is a recipe for making a common, contemporary oily peanut grit. It does not have the key steps (which would be difficult to achieve in a kitchen) for making stable, creamy peanut butter that were developed in 1922 by Joseph L. Rosefield.

Carver's original uses for peanuts include radical substitutes for existing products such as gasoline and nitroglycerin. These products remain mysterious because Carver never published his formulas, except for his peanut cosmetic patent. Many of them may only have been hypothetical proposals. Without Carver's formulas, others could not determine if his products were worthwhile or manufacture them. Thus, the widespread claims that Carver's peanut inventions revolutionized Southern agriculture by creating large new markets for peanuts have no factual basis.[8] Exaggerations of the number and impact of Carver's inventions are why historians now consider Carver's scientific reputation to be substantially mythical [9].

The rise in U.S. peanut production in the early 1900s was actually due mainly to the following: [10]

- The boll weevil's devastation of cotton farming

- The growing popularity of peanut butter after John Harvey Kellogg began promoting it as a health food in the 1890s

- Introduction of a big-selling roasted peanut vending machine in 1901

- The start of major commercial production of peanut candy in 1901

- Introduction of a peanut picking machine in 1905

- Increased demand for peanut oil during World War I due to wartime shortages of other plant oils

Despite a common claim that Carver never tried to profit from his inventions, Carver did market a few of his peanut products. None was successful enough to sell for long. The Carver Penol Company sold a mixture of creosote and peanuts as a patent medicine for respiratory diseases such as tuberculosis. Other ventures were The Carver Products Company and the Carvoline Company. Carvoline Antiseptic Hair Dressing was a mix of peanut oil and lanolin. Carvoline Rubbing Oil was a peanut oil for massages. Carver received national publicity in the 1930s when he concluded that his peanut oil massage was a cure for polio. It was eventually determined that the massage produced the benefit, not the peanut oil. Carver had been a trainer for the Iowa State football team and was experienced in giving massages.

Carver bulletins

During his time at Tuskegee (over four decades), Carver's official published work consisted mainly of 44 practical bulletins for farmers.[11] His first bulletin in 1898 was on feeding acorns to farm animals. His final bulletin in 1943 was about the peanut. He also published six bulletins on sweet potatoes, five on cotton and four on cowpeas. Some other individual bulletins dealt with alfalfa, wild plum, tomato, ornamental plants, corn, poultry, dairying, hogs, preserving meats in hot weather and nature study in schools.

His most popular bulletin, How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing it for Human Consumption, was first published in 1916[12] and reprinted many times. It gave a short overview of peanut crop production but was mainly a list of recipes from other agricultural bulletins, cookbooks, magazines and newspapers, such as the Peerless Cookbook,Good Housekeeping and Berry's Fruit Recipes. Many people mistakenly believe that Carver created the 105 peanut recipes and that Carver was first to promote peanuts as a replacement crop for cotton. Carver's was far from the first American agricultural bulletin devoted to peanuts.[13][14][15][16][17] Nor was it the first agricultural bulletin on peanut recipes, since Mrs. Jessie P. Rich of the University of Texas published "Uses of the Peanut on the Home Table" in 1915.[18] It is notable that Carver's 1916 peanut bulletin did not mention any of the novel industrial uses for peanuts that he later advocated. His 1916 bulletin came right before U.S. peanut production peaked in 1917, and then declined. Peanut production did not reach the 1917 level again until 1927.

Troubles at Tuskegee

Carver had numerous problems at Tuskegee before he became famous. Carver's initial arrogance, his higher than normal salary and the two rooms he received for his personal use were resented by other faculty.[19] Single faculty members normally bunked two to a room. One of Carver's duties was to administer the Agricultural Experiment Station farms. He was expected to produce and sell farm products to make a profit. He soon proved to be a poor administrator. In 1900, Carver complained that the physical work and the letter-writing his agricultural work required were both too much for him.[20]

In 1902, Booker T. Washington invited a nationally famous woman photographer to Tuskegee. Carver and Nelson Henry, a Tuskegee graduate, accompanied the attractive white woman in the town of Ramer. Several white citizens thought Henry was improperly associating with a white woman. Someone fired three pistol shots at Henry and he fled. Mobs prevented him from returning. Carver considered himself fortunate to escape alive.[21]

In 1904, a committee reported that Carver's reports on the poultry yard were exaggerated, and Washington criticized Carver about the exaggerations. Carver replied to Washington "Now to be branded as a liar and party to such hellish deception it is more than I can bear, and if your committee feel that I have willfully lied or [was] party to such lies as were told my resignation is at your disposal." [22] In 1910, Carver submitted a letter of resignation in response to a reorganization of the agriculture programs.[23]: Carver again threatened to resign in 1912 over his teaching assignment.[24] Carver submitted a letter of resignation in 1913, with the intention of heading up an experiment station elsewhere.[25] He also threatened to resign in 1913 and 1914 when he didn't get a summer teaching assignment [26][27] In each case, Washington smoothed things over. It seemed that Carver's wounded pride prompted most of the resignation threats, especially the last two because he did not need the money from summer work.

In 1911, Washington wrote a lengthy letter to Carver complaining that Carver did not follow orders to plant certain crops at the experiment station.[28] He also refused Carver's demands for a new laboratory and research supplies for Carver's exclusive use and for Carver to teach no classes. He complimented Carver's abilities in teaching and original research but bluntly stated his poor administrative skills, "When it comes to the organization of classes, the ability required to secure a properly organized and large school or section of a school, you are wanting in ability. When it comes to the matter of practical farm managing which will secure definite, practical, financial results, you are wanting again in ability." Also in 1911, Carver complained that his laboratory was still without the equipment promised 11 months earlier. At the same time, Carver complained of committees criticizing him and that his "nerves will not stand" any more committee meetings.[29]

Cultural references

In the 2002 movie Undercover Brother, Conspiracy Brother, played by comedian Dave Chappelle, laments how black people don't get credit for anything. To make his point, he claims, "Did you know that George Washington Carver made the first computer from a peanut?"

Many comedians, such as Eddie Murphy in his "Black History Minute" sketch on Saturday Night Live have humorously suggested that Carver invented peanut butter, but that the idea was "stolen" from him by individuals variously named "Skippy" or "Jiffy". (Some of these jokes intersect with the truth, given that the real inventor of modern peanut butter, Joseph L. Rosefield, marketed and trademarked Skippy.)

A teenage genetic clone of George Washington Carver is a recurring character in the TV show Clone High. In the show, the character is obsessed with peanuts.

In the 'Round Springfield episode of The Simpsons, Marge asked Bart who was George Washington Carver and he replied, "The guy who carved up George Washington."

In an episode of The Tick cartoon a villain uses a time machine to bring the mankind's most intelligent minds so he can take their knowledge to himself, among others, he also brings George Washington Carver.

Trivia

- George Washington Carver Recognition Day is celebrated every January 5, on the day Carver died, because his birthdate is unknown.

- After Thomas Edison's death in 1931, Carver claimed in speeches that Edison offered him a job at the then huge salary of $100,000 or $200,000 per year depending on the speech. Carver earned about $1,000 per year when he started at Tuskegee. Edison's associates could never confirm the job offer.

- Carver was exceptionally frugal. He saved most of his yearly salary because his room and board were free.

- Carver lived on the second floor of a women's dormitory at Tuskegee and accessed his room via the fire escape.

- Carver was an unorthodox scientist. He claimed that God gave him the ideas for his plant products, and he never wrote down the formulas but kept them all in his head.

- Carver was often evasive when others requested more details on his inventions. When the Farm Security Administration asked for a list of Carver's peanut products, Carver replied "I do not attempt to keep a list, as a list today would not be the same tomorrow, if I am allowed to work on that particular product."

- Carver was a talented artist and exhibited two paintings at the 1893 World's Fair.

- Carver often clashed with his boss, Booker T. Washington. Carver wanted to spend all his time on research and not do the administration, committee work and teaching his boss also required. After Washington's death in 1915, Carver was allowed to spend almost full time on research.

- Carver always had a flower or piece of living plant in his lapel and used it as a way to teach about the plant.

See also

- African-American history

- Boll Weevil

- Peanut

- Carver Academy

- List of people on stamps of the United States

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Pages 9-10 of George Washington Carver: Scientist and Symbol by Linda McMurry, 1982. New York: Oxford University Press (ISBN 0-19-503205-5)

- ↑ Page 10 of McMurry

- ↑ http://www.nps.gov/gwca/index.htm

- ↑ Mackintosh, Barry. 1977. George Washington Carver and the Peanut: New Light on a Much-loved Myth. American Heritage 28(5): 66-73. [1]

- ↑ Carver, George Washington. 1916. How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing it for Human Consumption. Tuskegee Institute Experimental Station Bulletin 31. [2]

- ↑ Page 88 of Peanuts: The Illustrious History of the Goober Pea by Andrew F. Smith, 2002. Chicago: University of Illinois Press (ISBN 0-252-02553-9) [3]

- ↑ List of By-Products From Peanuts By George Washington Carver (as compiled by the Carver Museum) [4]

- ↑ Mackintosh, Barry. 1977. George Washington Carver and the Peanut: New Light on a Much-loved Myth. American Heritage 28(5): 66-73. [5]

- ↑ Page 127 of The Booker T. Washington Papers, Volume 4 by Louis R. Harlan, Ed., 1975. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. ISBN (025201152X) [6]

- ↑ Pages 412-413 of Crop Production : Evolution, History, and Technology. by C. Wayne Smith, 1995. New York: Wiley (ISBN 0-471-07972-3) [7]

- ↑ List of Bulletins by George Washington Carver [8]

- ↑ Carver, George Washington. 1916. "How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing it for Human Consumption." Tuskegee Institute Experimental Station Bulletin 31. [9]

- ↑ Handy, R.B. 1895. Peanuts: Culture and Uses. USDA Farmers' Bulletin 25.

- ↑ Newman, C.L. 1904. Peanuts. Fayetteville, Arkansas: Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station.

- ↑ Beattie, W.R. 1909. Peanuts. USDA Farmers' Bulletin 356.

- ↑ Ferris, E.B. 1909. Peanuts. Agricultural College, Mississippi: Mississippi Agricultural Experiment Station.

- ↑ Beattie, W.R. 1911. The Peanut. USDA Farmers' Bulletin 431.

- ↑ Rich, J.P. 1915. Uses of the Peanut on the Home Table. Farmer's Bulletin 13. University of Texas, Austin.

- ↑ Pages 45-47 of McMurry

- ↑ Volume 5, page 481 of Harlan

- ↑ Volume 5, page 504 of Harlan

- ↑ Volume 8, page 95 of Harlan

- ↑ Volume 10, page 480 of Harlan

- ↑ Volume 12, page 95 of Harlan

- ↑ Volume 12, pages 251-252 of Harlan

- ↑ Volume 12, page 201 of Harlan

- ↑ Volume 13, page 35 of Harlan

- ↑ Volume 10, pages 592-596 of Harlan

- ↑ Volume 4, page 239 of Harlan

- Carver, George Washington. "1897 or Thereabouts: George Washington Carver's Own Brief History of His Life." George Washington Carver National Monument.

- Kremer, Gary R. (editor). 1987. George Washington Carver in His Own Words. Columbia, Missouri.: University of Missouri Press.

- Mackintosh, Barry, "George Washington Carver: The Making of a Myth" The Journal of Southern History,Vol. XLII, No. 4, November 1976, pp. 507-528 [11]

- McMurry, L. O. Carver, George Washington. American National Biography Online Feb. 2000

External links

- Tuskegee University, Carver tribute

- Iowa State University, The Legacy of George Washington Carver

- Peter D. Burchard, "George Washington Carver: For His Time and Ours," National Parks Service: George Washington Carver National Monument. 2006.

- Mark Hersey, "Hints and Suggestions to Farmers: George Washington Carver and Rural Conservation in the South," Environmental History April 2006

- George Washington CarverA Prolific Innovator, Artist, and Botanist

Template:Botanist

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Carver, George Washington |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | botanist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1865 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Diamond, Missouri, United States of America |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 5, 1943 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Tuskegee, Alabama, United States of America |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.