Eugenics

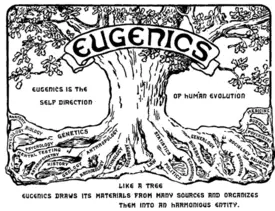

Eugenics is a social philosophy which advocates the improvement of human hereditary traits through various forms of intervention.

The purported goals have variously been to create healthier, more intelligent people, save society's resources, and lessen human suffering.

Earlier proposed means of achieving these goals focused on selective breeding, while modern ones focus on prenatal testing and screening, genetic counseling, birth control, in vitro fertilization, and genetic engineering. Opponents argue that eugenics is immoral and is based on, or is itself, pseudoscience. Historically, eugenics has been used as a justification for coercive state-sponsored discrimination and human rights violations, such as forced sterilization of persons with genetic defects, the killing of the institutionalized and, in some cases, genocide of races perceived as inferior.

Definition

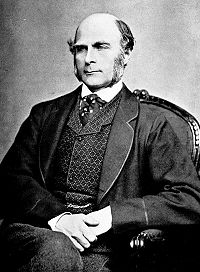

The word eugenics etymologically derives from the Greek words eu (good) and gen (birth), and was coined by Francis Galton in 1883.

The term eugenics is often used to refer to movements and social policies that were influential during the early 20th century. In a historical and broader sense, eugenics can also be a study of "improving human genetic qualities." It is sometimes broadly applied to describe any human action whose goal is to improve the gene pool. Some forms of infanticide in ancient societies, present-day reprogenetics, preemptive abortions and designer babies have been (sometimes controversially) referred to as eugenic.

Purpose

Eugenicists advocate specific policies that (if successful) would lead to a perceived improvement of the human gene pool. Since defining what improvements are desired or beneficial is by many perceived as a cultural choice rather than a matter that can be determined objectively (e.g., by empirical, scientific inquiry), eugenics has often been deemed a pseudoscience. The most disputed aspect of eugenics has been the definition of "improvement" of the human gene pool, such as what is a beneficial characteristic and what is a defect. This aspect of eugenics has historically been tainted with scientific racism.

Early eugenicists were mostly concerned with perceived intelligence factors that often correlated strongly with social class. Many eugenicists took inspiration from the selective breeding of animals (where purebreds are often strived for) as their analogy for improving human society. The mixing of races (or miscegenation) was usually considered as something to be avoided in the name of racial purity. At the time this concept appeared to have some scientific support, and it remained a contentious issue until the advanced development of genetics led to a scientific consensus that the division of the human species into unequal races is unjustifiable. Some see this as an ideological consensus, since equality, just like inequality, is a cultural choice rather than a matter that can be determined objectively.

Eugenics has also been concerned with the elimination of hereditary diseases such as haemophilia and Huntington's disease. However, there are several problems with labeling certain factors as "genetic defects." In many cases there is no scientific consensus on what a "genetic defect" is. It is often argued that this is more a matter of social or individual choice. What appears to be a "genetic defect" in one context or environment may not be so in another. This can be the case for genes with a heterozygote advantage, such as sickle cell anemia or Tay-Sachs disease, which in their heterozygote form may offer an advantage against, respectively, malaria and tuberculosis. Many people can succeed in life with disabilities. Many of the conditions early eugenicists identified as inheritable (pellagra is one such example) are currently considered to be at least partially, if not wholly, attributed to environmental conditions. Similar concerns have been raised when a prenatal diagnosis of a congenital disorder leads to abortion (see also preimplantation genetic diagnosis).

Eugenic policies have been conceptually divided into two categories: positive eugenics, which encourage a designated "most fit" to reproduce more often; and negative eugenics, which discourage or prevent a designated "less fit" from reproducing. Negative eugenics need not be coercive. A state might offer financial rewards to certain people who submit to sterilization, although some critics might reply that this incentive along with social pressure could be perceived as coercion. Positive eugenics can also be coercive. Abortion by "fit" women was illegal in Nazi Germany.

During the 20th century, many countries enacted various eugenics policies and programs, including:

- Genetic screening

- Birth control

- Promoting differential birth rates

- Marriage restrictions

- Immigration control

- Segregation (both racial segregation as well as segregation of the mentally ill from the normal)

- Compulsory sterilization

- Forced Abortions

- Genocide

Most of these policies were later regarded as coercive, restrictive, or genocidal, and now few jurisdictions implement policies that are explicitly labeled as eugenic or unequivocally eugenic in substance (however labeled). However, some private organizations assist people in genetic counseling, and reprogenetics may be considered as a form of non-state-enforced "liberal" eugenics.

History

Pre-Galton eugenics

Selective breeding was suggested at least as far back as Plato, who believed human reproduction should be controlled by government. He recorded these ideals in The Republic: "The best men must have intercourse with the best women as frequently as possible, and the opposite is true of the very inferior." Plato proposed that the process be concealed from the public via a form of lottery. Other ancient examples include the polis of Sparta's purported practice of infanticide. However, they would leave all babies outside for a length of time, and the survivors were considered stronger, while many "weaker" babies perished.[1]

Galton's theory

During the 1860s and 1870s, Sir Francis Galton systematized these ideas and practices according to new knowledge about the evolution of man and animals provided by the theory of his cousin Charles Darwin. After reading Darwin's Origin of Species, Galton noticed an interpretation of Darwin's work whereby the mechanisms of natural selection were potentially thwarted by human civilization. He reasoned that, since many human societies sought to protect the underprivileged and weak, those societies were at odds with the natural selection responsible for extinction of the weakest. Only by changing these social policies, Galton thought, could society be saved from a "reversion towards mediocrity," a phrase that he first coined in statistics and which later changed to the now common "regression towards the mean".[2]

Galton first sketched out his theory in the 1865 article "Hereditary Talent and Character," then elaborated it further in his 1869 book Hereditary Genius.[3] He began by studying the way in which human intellectual, moral, and personality traits tended to run in families. Galton's basic argument was that "genius" and "talent" were hereditary traits in humans (although neither he nor Darwin yet had a working model of this type of heredity). He concluded that, since one could use artificial selection to exaggerate traits in other animals, one could expect similar results when applying such models to humans. As he wrote in the introduction to Hereditary Genius:

- I propose to show in this book that a man's natural abilities are derived by inheritance, under exactly the same limitations as are the form and physical features of the whole organic world. Consequently, as it is easy, notwithstanding those limitations, to obtain by careful selection a permanent breed of dogs or horses gifted with peculiar powers of running, or of doing anything else, so it would be quite practicable to produce a highly-gifted race of men by judicious marriages during several consecutive generations.[4]

According to Galton, society already encouraged dysgenic conditions, claiming that the less intelligent were out-reproducing the more intelligent. Galton did not propose any selection methods; rather, he hoped that a solution would be found if social mores changed in a way that encouraged people to see the importance of breeding.

Galton first used the word eugenic in his 1883 Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development, a book in which he meant "to touch on various topics more or less connected with that of the cultivation of race, or, as we might call it, with 'eugenic' questions." He included a footnote to the word "eugenic" which read:

- That is, with questions bearing on what is termed in Greek, eugenes namely, good in stock, hereditarily endowed with noble qualities. This, and the allied words, eugeneia, etc., are equally applicable to men, brutes, and plants. We greatly want a brief word to express the science of improving stock, which is by no means confined to questions of judicious mating, but which, especially in the case of man, takes cognisance of all influences that tend in however remote a degree to give to the more suitable races or strains of blood a better chance of prevailing speedily over the less suitable than they otherwise would have had. The word eugenics would sufficiently express the idea; it is at least a neater word and a more generalised one than viriculture which I once ventured to use.[5]

In 1904 he clarified his definition of eugenics as "the science which deals with all influences that improve the inborn qualities of a race; also with those that develop them to the utmost advantage."[6]

Galton's formulation of eugenics was based on a strong statistical approach, influenced heavily by Adolphe Quetelet's "social physics." Unlike Quetelet, however, Galton did not exalt the "average man" but decried him as mediocre. Galton and his statistical heir Karl Pearson developed what was called the biometrical approach to eugenics, which developed new and complex statistical models (later exported to wholly different fields) to describe the heredity of traits. However, with the rediscovery of Gregor Mendel's hereditary laws, two separate camps of eugenics advocates emerged. One was made up of statisticians, the other of biologists. Statisticians thought the biologists had exceptionally crude mathematical models, while biologists thought the statisticians knew little about biology.[7]

Eugenics eventually referred to human selective reproduction with an intent to create children with desirable traits, generally through the approach of influencing differential birth rates. These policies were mostly divided into two categories: positive eugenics, the increased reproduction of those seen to have advantageous hereditary traits; and negative eugenics, the discouragement of reproduction by those with hereditary traits perceived as poor. Negative eugenic policies in the past have ranged from attempts at segregation to sterilization and even genocide. Positive eugenic policies have typically taken the form of awards or bonuses for "fit" parents who have another child. Relatively innocuous practices like marriage counseling had early links with eugenic ideology.

Eugenics differed from what would later be known as Social Darwinism. While both claimed intelligence was hereditary, eugenics asserted that new policies were needed to actively change the status quo towards a more "eugenic" state, while the Social Darwinists argued society itself would naturally "check" the problem of "dysgenics" if no welfare policies were in place (for example, the poor might reproduce more but would have higher mortality rates).

Eugenics and the state, 1890s–1945

One of the earliest modern advocates of eugenic ideas (before they were labeled as such) was Alexander Graham Bell. In 1881 Bell investigated the rate of deafness on Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts. From this he concluded that deafness was hereditary in nature and recommended a marriage prohibition against the deaf ("Memoir upon the formation of a deaf variety of the human Race") even though he was married to a deaf woman. Like many other early eugenicists, he proposed controlling immigration for the purpose of eugenics and warned that boarding schools for the deaf could possibly be considered as breeding places of a deaf human race.[8]

Though eugenics is today often associated with racism, it was not always so; both W.E.B. DuBois and Marcus Garvey supported eugenics or ideas resembling eugenics as a way to reduce African American suffering and improve their stature.[9] Many legal methods of eugenics include state laws against miscegenation or prohibitions of interracial marriage. The U.S. Supreme Court overturned those state laws in 1967 and declared antimiscegenation laws unconstitutional.

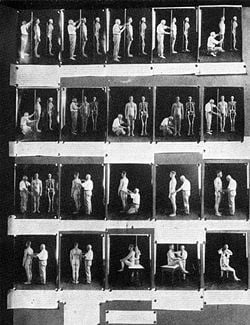

Nazi Germany under Adolf Hitler was infamous for eugenics programs which attempted to maintain a "pure" German race through a series of programs that ran under the banner of "racial hygiene." Among other activities, the Nazis performed extensive experimentation on live human beings to test their genetic theories, ranging from simple measurement of physical characteristics to the horrific experiments carried out by Josef Mengele for Otmar von Verschuer on twins in the concentration camps. During the 1930s and 1940s, the Nazi regime forcibly sterilized hundreds of thousands of people whom they viewed as mentally and physically "unfit," an estimated 400,000 between 1934 and 1937. The scale of the Nazi program prompted American eugenics advocates to seek an expansion of their program, with one complaining that "the Germans are beating us at our own game".[10] The Nazis went further, however, killing tens of thousands of the institutionalized disabled through compulsory "euthanasia" programs.[11]

They also implemented a number of "positive" eugenics policies, giving awards to "Aryan" women who had large numbers of children and encouraged a service in which "racially pure" single women were impregnated by SS officers (Lebensborn). Many of their concerns for eugenics and racial hygiene were also explicitly present in their systematic killing of millions of "undesirable" people including Jews, gypsies, Jehovah's Witnesses and homosexuals during the Holocaust (much of the killing equipment and methods employed in the death camps were first developed in the euthanasia program). The scope and coercion involved in the German eugenics programs along with a strong use of the rhetoric of eugenics and so-called "racial science" throughout the regime created an indelible cultural association between eugenics and the Third Reich in the postwar years.[12]

The second largest eugenics movement was in the United States. Beginning with Connecticut in 1896, many states enacted marriage laws with eugenic criteria, prohibiting anyone who was "epileptic, imbecile or feeble-minded" from marrying. In 1898 Charles B. Davenport, a prominent American biologist, began as director of a biological research station based in Cold Spring Harbor where he experimented with evolution in plants and animals. In 1904 Davenport received funds from the Carnegie Institution to found the Station for Experimental Evolution. The Eugenics Record Office opened in 1910 while Davenport and Harry H. Laughlin began to promote eugenics.[13]

During the 20th century, researchers became interested in the idea that mental illness could run in families and conducted a number of studies to document the heritability of such illnesses as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression. Their findings were used by the eugenics movement as proof for its cause. State laws were written in the late 1800s and early 1900s to prohibit marriage and force sterilization of the mentally ill in order to prevent the "passing on" of mental illness to the next generation. These laws were upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1927 and were not abolished until the mid-20th century. By 1945 over 45,000 mentally ill individuals in the United States had been forcibly sterilized.

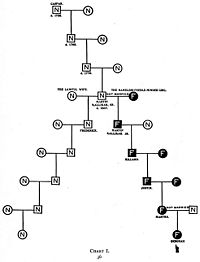

In years to come, the ERO collected a mass of family pedigrees and concluded that those who were unfit came from economically and socially poor backgrounds. Eugenicists such as Davenport, the psychologist Henry H. Goddard and the conservationist Madison Grant (all well respected in their time) began to lobby for various solutions to the problem of the "unfit." (Davenport favored immigration restriction and sterilization as primary methods; Goddard favored segregation in his The Kallikak Family; Grant favored all of the above and more, even entertaining the idea of extermination.)[14] It did, however, have scientific detractors (notably, Thomas Hunt Morgan, one of the few Mendelians to explicitly criticize eugenics), though most of these focused more on what they considered the crude methodology of eugenicists, and the characterization of almost every human characteristic as being hereditary, rather than the idea of eugenics itself.[15]

The idea of "genius" and "talent" is also considered by William Graham Sumner, a founder of the American Sociological Society (now called the American Sociological Association). He maintained that if the government did not meddle with the social policy of laissez-faire, a class of genius would rise to the top of the system of social stratification, followed by a class of talent. Most of the rest of society would fit into the class of mediocrity. Those who were considered to be defective (mentally retarded, handicapped, etc.) had a negative effect on social progress by draining off necessary resources. They should be left on their own to sink or swim. But those in the class of delinquent (criminals, deviants, etc.) should be eliminated from society ("Folkways," 1907).

With the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924, eugenicists for the first time played a central role in the Congressional debate as expert advisers on the threat of "inferior stock" from eastern and southern Europe. This reduced the number of immigrants from abroad to 15 percent from previous years, to control the number of "unfit" individuals entering the country. The new act strengthened existing laws prohibiting race mixing in an attempt to maintain the gene pool.[16] Eugenic considerations also lay behind the adoption of incest laws in much of the U.S. and were used to justify many antimiscegenation laws.[17]

Some states sterilized "imbeciles" for much of the 20th century. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the 1927 Buck v. Bell case that the state of Virginia could sterilize those it thought unfit. The most significant era of eugenic sterilization was between 1907 and 1963, when over 64,000 individuals were forcibly sterilized under eugenic legislation in the United States.[18] A favorable report on the results of sterilization in California, by far the state with the most sterilizations, was published in book form by the biologist Paul Popenoe and was widely cited by the Nazi government as evidence that wide-reaching sterilization programs were feasible and humane. When Nazi administrators went on trial for war crimes in Nuremberg after World War II, they justified the mass sterilizations (over 450,000 in less than a decade) by citing the United States as their inspiration.[19]

Other countries

Almost all non-Catholic Western nations adopted some eugenic legislations. In July 1933 Germany passed a law allowing for the involuntary sterilization of "hereditary and incurable drunkards, sexual criminals, lunatics, and those suffering from an incurable disease which would be passed on to their offspring."[20] Two provinces in Canada carried out thousands of compulsory sterilizations, and these lasted into the 1970s. Many First Nations (native Canadians) were targeted, as well as immigrants from Eastern Europe, as the program identified racial and ethnic minorities to be genetically inferior. Sweden forcibly sterilized 62,000 people, primarily the mentally ill in the later decades, but also ethnic or racial minorities early on, as part of a eugenics program over a 40-year period. As was the case in other programs, ethnicity and race were believed to be connected to mental and physical health. While many Swedes disliked the program, politicians generally supported it; the ruling left supported it more as a means of promoting social health, while amongst the right it was more about racial protectionism. (The Swedish government has subsequently paid damages to those involved.) Besides the large-scale program in the United States, other nations included Australia, the UK, Norway, France, Finland, Denmark, Estonia, Iceland, and Switzerland with programs to sterilize people the government declared to be mentally deficient. Singapore practiced a limited form of eugenics that involved encouraging marriage between university graduates and the rest through segregation in matchmaking agencies, in the hope that the former would produce better children.[21]

Various authors, notably Stephen Jay Gould, have repeatedly asserted that restrictions on immigration passed in the United States during the 1920s (and overhauled in 1965) were motivated by the goals of eugenics, in particular, a desire to exclude races considered to be inferior from the national gene pool. During the early 20th century, the United States and Canada began to receive far higher numbers of Southern and Eastern European immigrants. Influential eugenicists like Lothrop Stoddard and Harry Laughlin (who was appointed as an expert witness for the House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization in 1920) presented arguments that these were inferior races that would pollute the national gene pool if their numbers went unrestricted. It has been argued that this stirred both Canada and the United States into passing laws creating a hierarchy of nationalities, rating them from the most desirable Anglo-Saxon and Nordic peoples to the Chinese and Japanese immigrants, who were almost completely banned from entering the country.[22] However, several people, in particular Franz Samelson, Mark Snyderman and Richard Herrnstein, have argued that, based on their examination of the records of the congressional debates over immigration policy, congress gave virtually no consideration to these factors. According to these authors, the restrictions were motivated primarily by a desire to maintain the country's cultural integrity against a heavy influx of foreigners.[23] This interpretation is not, however, accepted by most historians of eugenics.

Some who disagree with the idea of eugenics in general contend that eugenics legislation still had benefits. Margaret Sanger (founder of Planned Parenthood of America) found it a useful tool to urge the legalization of contraception. In its time eugenics was seen by many as scientific and progressive, the natural application of knowledge about breeding to the arena of human life. Before the death camps of World War II, the idea that eugenics could lead to genocide was not taken seriously.

Stigmatization of eugenics in the post-Nazi years

After the experience of Nazi Germany, many ideas about "racial hygiene" and "unfit" members of society were publicly renounced by politicians and members of the scientific community. The Nuremberg Trials against former Nazi leaders revealed to the world many of the regime's genocidal practices and resulted in formalized policies of medical ethics and the 1950 UNESCO statement on race. Many scientific societies released their own similar "race statements" over the years, and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, developed in response to abuses during the Second World War, was adopted by the United Nations in 1948 and affirmed, "Men and women of full age, without any limitation due to race, nationality or religion, have the right to marry and to found a family."[24] In continuation, the 1978 UNESCO declaration on race and racial prejudice states that the fundamental equality of all human beings is the ideal toward which ethics and science should converge.[25]

In reaction to Nazi abuses, eugenics became almost universally reviled in many of the nations where it had once been popular (however, some eugenics programs, including sterilization, continued quietly for decades). Many pre-war eugenicists engaged in what they later labeled "crypto-eugenics," purposefully taking their eugenic beliefs "underground" and becoming respected anthropologists, biologists and geneticists in the postwar world (including Robert Yerkes in the U.S. and Otmar von Verschuer in Germany). Californian eugenicist Paul Popenoe founded marriage counseling during the 1950s, a career change which grew from his eugenic interests in promoting "healthy marriages" between "fit" couples.[26]

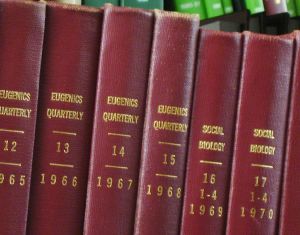

High school and college textbooks from the 1920s through the '40s often had chapters touting the scientific progress to be had from applying eugenic principles to the population. Many early scientific journals devoted to heredity in general were run by eugenicists and featured eugenics articles alongside studies of heredity in nonhuman organisms. After eugenics fell out of scientific favor, most references to eugenics were removed from textbooks and subsequent editions of relevant journals. Even the names of some journals changed to reflect new attitudes. For example, Eugenics Quarterly became Social Biology in 1969 (the journal still exists today, though it looks little like its predecessor). Notable members of the American Eugenics Society (1922–94) during the second half of the 20th century included Joseph Fletcher, originator of Situational ethics; Dr. Clarence Gamble of the Procter & Gamble fortune; and Garrett Hardin, a population control advocate and author of The Tragedy of the Commons.

Despite the changed postwar attitude towards eugenics in the U.S. and some European countries, a few nations, notably, Canada and Sweden, maintained large-scale eugenics programs, including forced sterilization of mentally handicapped individuals, as well as other practices, until the 1970s. In the United States, sterilizations capped off in the 1960s, though the eugenics movement had largely lost most popular and political support by the end of the 1930s.[27]

Criticism

Ethical re-evaluation

In modern bioethics literature, the history of eugenics presents many moral and ethical questions. Commentators have suggested the new "eugenics" will come from reproductive technologies that will allow parents to create so-called "designer babies" (what the biologist Lee M. Silver prominently called "reprogenetics"). It has been argued that this "non-coercive" form of biological "improvement" will be predominantly motivated by individual competitiveness and the desire to create "the best opportunities" for children, rather than an urge to improve the species as a whole, which characterized the early 20th-century forms of eugenics. Because of this non-coercive nature, lack of involvement by the state and a difference in goals, some commentators have questioned whether such activities are eugenics or something else altogether.

Some disability activists argue that, although their impairments may cause them pain or discomfort, what really disables them as members of society is a sociocultural system that does not recognize their right to genuinely equal treatment. They express skepticism that any form of eugenics could be to the benefit of the disabled considering their treatment by historical eugenic campaigns.

James D. Watson, the first director of the Human Genome Project, initiated the Ethical, Legal and Social Implications Program (ELSI) which has funded a number of studies into the implications of human genetic engineering (along with a prominent website on the history of eugenics), because:

- In putting ethics so soon into the genome agenda, I was responding to my own personal fear that all too soon critics of the Genome Project would point out that I was a representative of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory that once housed the controversial Eugenics Record Office. My not forming a genome ethics program quickly might be falsely used as evidence that I was a closet eugenicist, having as my real long-term purpose the unambiguous identification of genes that lead to social and occupational stratification as well as genes justifying racial discrimination.[28]

Distinguished geneticists including Nobel Prize-winners John Sulston ("I don't think one ought to bring a clearly disabled child into the world")[29] and Watson ("Once you have a way in which you can improve our children, no one can stop it")[30] support genetic screening. Which ideas should be described as "eugenic" are still controversial in both public and scholarly spheres. Some observers such as Philip Kitcher have described the use of genetic screening by parents as making possible a form of "voluntary" eugenics.[31]

Some modern subcultures advocate different forms of eugenics assisted by human cloning and human genetic engineering, sometimes even as part of a new cult (see Raëlism, Cosmotheism, or Prometheism). These groups also talk of "neo-eugenics." "conscious evolution," or "genetic freedom."

Behavioral traits often identified as potential targets for modification through human genetic engineering include intelligence, depression, schizophrenia, alcoholism, sexual behavior (and orientation) and criminality.

In a 2005 United Kingdom court case, the Crown v. James Edward Whittaker-Williams, arguably set a precedent of banning sexual contact between people with "learning difficulties." The accused, a man suffering learning disabilities, was jailed for kissing and hugging a woman with learning disabilities. This was done under the 2003 Sexual Offences Act, which redefines kissing and cuddling as sexual and states that those with learning difficulties are unable to give consent regardless of whether or not the act involved coercion. Opponents of the act have attacked it as bringing in eugenics through the backdoor under the guise of a requirement of "consent".[32]

Diseases vs. traits

While the science of genetics has increasingly provided means by which certain characteristics and conditions can be identified and understood, given the complexity of human genetics, culture, and psychology there is at this point no agreed objective means of determining which traits might be ultimately desirable or undesirable. Eugenic manipulations that reduce the propensity for criminality and violence, for example, might result in the population being enslaved by an outside aggressor it can no longer defend itself against. On the other hand, genetic diseases like hemochromatosis can increase susceptibility to illness, cause physical deformities, and other dysfunctions. Eugenic measures against many of these diseases are already being undertaken in societies around the world, while measures against traits that affect more subtle, poorly understood traits, such as criminality, are relegated to the realm of speculation and science fiction. The effects of diseases are essentially wholly negative, and societies everywhere seek to reduce their impact by various means, some of which are eugenic in all but name.

Slippery slope

A common criticism of eugenics is that it inevitably leads to measures that are unethical (Lynn 2001). In the hypothetical scenario where it's scientifically proven that one racial minority group making up 5% of the population is on average less intelligent than the majority racial group it's more likely that the minority racial group will be submitted to a eugenics program, opposed to the 5% least intelligent members of the population as a whole. For example, Nazi Germany's eugenic program within the German population resulted in protests and unrest, while the persecution of the Jews was met with silence.

H. L. Kaye wrote of "the obvious truth that eugenics has been discredited by Hitler's crimes" (Kaye 1989). R. L. Hayman argued "the eugenics movement is an anachronism, its political implications exposed by the Holocaust" (Hayman 1990).

Steven Pinker has stated that it is "a conventional wisdom among left-leaning academics that genes imply genocide." He has responded to this "conventional wisdom" by comparing the history of Marxism, which had the opposite position on genes to that of Nazism:

But the 20th century suffered "two" ideologies that led to genocides. The other one, Marxism, had no use for race, didn't believe in genes and denied that human nature was a meaningful concept. Clearly, it's not an emphasis on genes or evolution that is dangerous. It's the desire to remake humanity by coercive means (eugenics or social engineering) and the belief that humanity advances through a struggle in which superior groups (race or classes) triumph over inferior ones.[33]

Richard Lynn argues that any social philosophy is capable of ethical misuse. Though Christian principles have aided in the abolition of slavery and the establishment of welfare programs, he notes that the Christian church has also burned many dissidents at the stake and waged wars against nonbelievers in which Christian crusaders slaughtered large numbers of women and children. Lynn argues the appropriate response is to condemn these killings, but believing that Christianity "inevitably leads to the extermination of those who do not accept its doctrines" is unwarranted (Lynn 2001).

Genetic diversity

Eugenic policies could also lead to loss of genetic diversity, in which case a culturally accepted improvement of the gene pool may, but would not necessarily, result in biological disaster due to increased vulnerability to disease, reduced ability to adapt to environmental change and other factors both known and unknown. This kind of argument from the precautionary principle is itself widely criticized. A long-term eugenics plan is likely to lead to a scenario similar to this because the elimination of traits deemed undesirable would reduce genetic diversity by definition.

Related to a decrease in diversity is the danger of non-recognition. That is, if everyone were beautiful and attractive, then it would be more difficult to distinguish between different individuals, due to the wide variety of ugly traits and otherwise non-attractive traits and combinations thereof that we use to recognize each other.

The possible elimination of the autism genotype is a significant political issue in the autism rights movement, which claims autism is a form of neurodiversity. Many advocates of Down Syndrome rights also consider Down Syndrome (Trisomy-21) a form of neurodiversity, though males with Down Syndrome are generally infertile.

Heterozygous recessive traits

In some instances efforts to eradicate certain single-gene mutations would be nearly impossible. In the event the condition in question was a heterozygous recessive trait, the problem is that by eliminating the visible unwanted trait, there are still as many genes for the condition left in the gene pool as were eliminated according to the Hardy-Weinberg principle, which states that a population's genetics are defined as pp+2pq+qq at equilibrium. With genetic testing it may be possible to detect all of the heterozygous recessive traits, but only at great cost with the current technology. Under normal circumstances it is only possible to eliminate a dominant allele from the gene pool. Recessive traits can be severely reduced, but never eliminated unless the complete genetic makeup of all members of the pool was known, as aforementioned. As only very few undesirable traits, such as Huntington's disease, are dominant, the practical value for "eliminating" traits is quite low.

Notes

- ↑ Patterson, Cynthia. ""Not Worth the Rearing": The Causes of Infant Exposure in Ancient Greece." Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-)

- ↑ See Chapter 3 in Donald A. MacKenzie, Statistics in Britain, 1865-1930: The social construction of scientific knowledge (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1981).

- ↑ Francis Galton, "Hereditary talent and character", Macmillan's Magazine 12 (1865): 157-166 and 318-327; Francis Galton, Hereditary genius: an inquiry into its laws and consequences (London: Macmillan, 1869).

- ↑ Galton, Hereditary Genius: 1.

- ↑ Francis Galton, Inquiries into human faculty and its development (London, Macmillan, 1883): 17, fn1.

- ↑ Francis Galton, "Eugenics: Its definition, scope, and aims," The American Journal of Sociology 10:1 (July 1904).

- ↑ See Chapters 2 and 6 in MacKenzie, Statistics in Britain.

- ↑ Alexander Graham Bell. AllExperts. Retrieved March 31, 2007.

- ↑ Racial Integrity or `Race Suicide': Virginia's Eugenic Movement, W. E. B. Du Bois, and the Work of Walter A. Plecker FindArticles. Retrieved March 31, 2007.

- ↑ Quoted in Selgelid, Michael J. 2000. Neugenics? Monash Bioethics Review 19 (4):9-33

- ↑ The Nazi eugenics policies are discussed in a number of sources. A few of the more definitive ones are Robert Proctor, Racial hygiene: Medicine under the Nazis (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988) and Dieter Kuntz, ed., Deadly medicine: creating the master race (Washington, DC: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2004) (online exhibit). On the development of the racial hygiene movement before National Socialism, see Paul Weindling, Health, race and German politics between national unification and Nazism, 1870-1945 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989).

- ↑ See Proctor, Racial hygiene, and Kuntz, ed., Deadly medicine.

- ↑ The history of eugenics in the United States is discussed at length in Mark Haller, Eugenics: Hereditarian attitudes in American thought (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1963) and Daniel Kevles, In the name of eugenics: Genetics and the uses of human heredity (New York: Knopf, 1985), the latter being the standard survey work on the subject.

- ↑ See Kevles, In the name of eugenics.

- ↑ Hamilton Cravens, The triumph of evolution: American scientists and the heredity-environment controversy, 1900-1941 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1978): 179.

- ↑ Paul Lombardo, "Eugenics Laws Restricting Immigration," essay in the Eugenics Archive, available online at http://www.eugenicsarchive.org/html/eugenics/essay9text.html.

- ↑ Paul Lombardo, "Eugenic Laws Against Race-Mixing," essay in the Eugenics Archive, available online at http://www.eugenicsarchive.org/html/eugenics/essay7text.html.

- ↑ Paul Lombardo, "Eugenic Sterilization Laws," essay in the Eugenics Archive, available online at http://www.eugenicsarchive.org/html/eugenics/essay8text.html.

- ↑ The connections between U.S. and Nazi eugenicists is discussed in Edwin Black, "Eugenics and the Nazis — the California connection," San Francisco Chronicle (9 November 2003), as well as Black's War Against the Weak (New York: Four Wars Eight Windows, 2003). Stefan Kühl's work, The Nazi connection: Eugenics, American racism, and German National Socialism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), is considered the standard scholarly work on the subject.

- ↑ "Sterilisation of the unfit - Nazi legislation," The Guardian (26 July 1933). Available online at [1].

- ↑ There are a number of works discussing eugenics in various countries around the world. For the history of eugenics in Scandinavia, see Gunnar Broberg and Nils Roll-Hansen, eds., Eugenics And the Welfare State: Sterilization Policy in Demark, Sweden, Norway, and Findland (Michigan State University Press, 2005). Another international approach is Mark B. Adams, ed., The Wellborn Science: Eugenics in Germany, France, Brazil, and Russia (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990).

- ↑ See Lombardo, "Eugenics Laws Restricting Immigration"; and Stephen Jay Gould, The mismeasure of man (New York: Norton, 1981).

- ↑ Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray, The Bell Curve (Free Press, 1994): 5; and Mark Syderman Richard Herrnstein, "Intelligence tests and the Immigration Act of 1924," American Psychologist 38 (1983): 986-995.

- ↑ Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Retrieved 2006-08-26.

- ↑ Declaration on Race and Racial Prejudice. Retrieved 2006-08-26.

- ↑ A discussion of the general changes in views towards genetics and race after World War II is: Elazar Barkan, The retreat of scientific racism: changing concepts of race in Britain and the United States between the world wars (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992).

- ↑ See Broberg and Nil-Hansen, ed., Eugenics And the Welfare State and Alexandra Stern, Eugenic nation: faults and frontiers of better breeding in modern America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005)

- ↑ James D. Watson, A passion for DNA: Genes, genomes, and society (Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2000): 202.

- ↑ Quoted in Brendan Bourne, "Scientist warns disabled over having children" The Sunday Times (Britain) (13 October 2004). Available online at http://www.timesonline.co.uk/article/0,,2087-1337781,00.html.

- ↑ Quoted in Mark Henderson, "Let's cure stupidity, says DNA pioneer," The Times (28 February 2003). Available online at http://www.timesonline.co.uk/printFriendly/0,,1-2-593687,00.html.

- ↑ Philip Kitcher, The Lives to Come (Penguin, 1997). Review available online at http://www.wellcome.ac.uk/en/genome/geneticsandsociety/hg16f009.html.

- ↑ McKellar, Ian (29 September 2005). Jail sentence for kiss and cuddle man. Hunts Post

- ↑ United Press International: Q&A: Steven Pinker of 'Blank Slate. Retrieved 2006-08-26.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Histories of eugenics (academic accounts)

- Elof Axel Carlson, The Unfit: A History of a Bad Idea (Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Press, 2001). ISBN 0-87969-587-0

- Daniel Kevles, In the name of eugenics: Genetics and the uses of human heredity (New York: Knopf, 1985).

- Dieter Kuntz, ed., Deadly medicine: creating the master race (Washington, DC: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2004). online exhibit

- Ruth C. Engs, The Eugenics Movement: An Encyclopedia. (Westport CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005). ISBN 0-313-32791-2.

- Histories of hereditarian thought

- Elazar Barkan, The retreat of scientific racism: changing concepts of race in Britain and the United States between the world wars (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992).

- Stephen Jay Gould, The mismeasure of man (New York: Norton, 1981).

- Ewen & Ewen, Typecasting: On the Arts and Sciences of Human Inequality (New York, Seven Stories Press, 2006).

- Criticisms of eugenics, historical and modern

- Edwin Black, War Against the Weak: Eugenics and America's Campaign to Create a Master Race (Four Walls Eight Windows, 2003). [2] ISBN 1-56858-258-7

- Dinesh D'Souza, The End of Racism (Free Press, 1995) ISBN 0-02-908102-5

- Robert L. Hayman, Presumptions of justice: Law, politics, and the mentally retarded parent. Harvard Law Review 1990, 103, 1202-71. (p. 1209)

- Joseph, J. (2004). The Gene Illusion: Genetic Research in Psychiatry and Psychology Under the Microscope.New York: Algora. (2003 United Kingdom Edition by PCCS Books)

- Joseph, J. (2005). The 1942 “Euthanasia” Debate in the American Journal of Psychiatry. History of Psychiatry, 16, 171-179.

- Joseph, J. (2006). The Missing Gene: Psychiatry, Heredity, and the Fruitless Search for Genes.New York: Algora.

- H. L. Kaye, The social meaning of modern biology 1987, New Haven, CT Yale University Press. (p. 46)

- Tom Shakespeare, "Back to the Future? New Genetics and Disabled People," Critical Social Policy 46:22-35 (1995)

- Wahlsten, D. (1997). Leilani Muir versus the Philosopher King: eugenics on trial in Alberta. Genetica 99: 185-198.

- Tom Shakespeare, Genetic Politics: from Eugenics to Genome, with Anne Kerr (New Clarion Press, 2002).

- Nancy Ordover, American Eugenics: Race, Queer Anatomy, and the Science of Nationalism (Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press, 2003). ISBN 0-8166-3559-5

- Gina Maranto, "Quest for Perfection: The Drive to Breed Better Human Beings" Diane Publishing Co. (June 1996) ISBN 0-7881-9431-3

External links

Anti-eugenics and historical websites

- Eugenics Archive - Historical Material on the Eugenics Movement (funded by the Human Genome Project)

- Shoaheducation.com:Eugenics

- University of Virginia Historical Collections: Eugenics

- "Deadly Medicine: Creating the Master Race" (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum exhibit)

- Vermont Eugenics: A documentary history

- Eugenics - A Psychiatric Responsibility (History of Eugenics in Germany)

- DNA: Pandora's Box - PBS documentary about DNA, the Human Genome Project, and questions about a "new" eugenics

- Fighting Fire with Fire: African Americans and Hereditarian Thinking, 1900-1942 - article on the support of eugenics by African American thinkers

- "Eugenics — Breeding a Better Citizenry Through Science", a historical critique from physical anthropologist Jonathan Marks

- "The Quest for a Perfect Society", from Awake! magazine (September 22, 2000)

- "Eugenics and other Evils",G K Chesteron's "Eugenics and other Evils." (1922)

- "Eugenics" - National Reference Center for Bioethics Literature Scope Note 28, features overview of eugenics history and annotated bibliography of historical literature

Pro-eugenics websites

- Eugenics - a planned evolution for life

- The Eugenics List - Yahoo group

- Future Generations Eugenics Portal

- Millennium Eugenics Section

- Mankind Quarterly

- Future Human Evolution: Eugenics in the Twenty-First Century by John Glad

- Creative Conscious Evolution: A Eugenics Directory

- Scandalizing the Science of Eugenics, editor's note, The Occidental Quarterly 4:1 (Spring 2004).

Other

- "As Gene Test Menu Grows, Who Gets to Choose?" Amy Harmon, New York Times (21 July 2004).

- "The Crimson Rivers" — a fiction movie in 2000.

- Yale Study: U.S. Eugenics Paralleled Nazi Germany by David Morgan Published on Tuesday, February 15, 2000 in the Chicago Tribune

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.