Ethnobotany

Ethnobotany is the systematic study of the relationships between plants and people. It is not simply the study of the human "use" of plants; rather, ethnobotany includes the placement of plants within their cultural context in particular societies, and the placement of peoples within their ecological contexts. Ethnobotanists examine:

- the culturally specific ways that humans perceive and classify different kinds of plants;

- the things they do to plants, such as destroying "weeds," protecting certain "wild" plants, and "domesticating" and planting specific kinds of food and medicinal plants; and

- the ways in which various members of the plant world influence human cultures, from the geopolitical influence of the demand for spices (which launched the Age of Exploration) to the hallucinogenic snuffs used by Amazonian shamans in religious rituals.

The term “ethnobotany” was coined in 1895 by J.M. Harshberger, an American botanist at the University of Pennsylvania. Modern ethnobotany is an interdisciplinary field drawing together scholars from anthropology, botany, archaeology, geography, medicine, linguistics, economics, landscape architecture, and pharmacology. It is considered a branch of ethnobiology, the study of past and present interrelationships between human cultures and the plants, animals, and other organisms in their environment. Like its parent field, ethnobotany makes apparent the connection between human cultural practices and the subdisciplines of biology.

Ethnobotanical studies range across space and time, from archaeological investigations of the role of plants in ancient civilizations (a subfield called archaeobotany) to the bioengineering of new crops. Furthermore, ethnobotany is not limited to nonindustrialized or nonurbanized societies. In fact, co-adaptation of plants and human cultures has changed – and perhaps intensified – in the context of urbanization and globalization in the 20th and 21st centuries. Nonetheless, indigenous, non-Westernized cultures play a crucial role in the field of inquiry, as a way of highlighting their previously undervalued knowledge of local ecology gained through centuries or even millennia of interaction with their biotic environment.

The significance of ethnobotanical study is manifold. The study of indigenous food production and local medicinal knowledge may have practical implications for developing sustainable agriculture and discovering new medicines. Ethnobotany also encourages an awareness of the importance of biodiversity and its link to cultural diversity, as well as a sophisticated understanding of the mutual influence (both beneficial and destructive) of plants and humans.

The influence of plants on human culture

Why might plants have come to function as the material basis for human culture? The combination of their immobility (terrestial plants must remain rooted in the soil) and tremendous production of cellulose makes plants a far more efficient and reliable as a source of building materials and food than animals.

The biochemical diversity of plants – which contributes to their myriad medicinal and culinary uses - might also be traced in part to their immobility. Plants produce chemicals as a way of interacting with other organisms in their environment for mutual gain - enlisting animals in the transport of pollen or seeds - or as a mechanism of defense, to repel or poison predators or parasites. Modern societies depend on chemical agents in plants for 25 percent of prescription drugs and nearly all recreational chemicals, such as the caffeine in coffee, the nicotine in tobacco, and the theophylline in tea.

Historic roots of ethnobotany

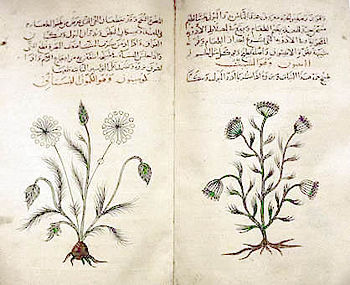

Although ethnobotany did not emerge as an academic discipline until the end of the 19th century, its roots extend back to Greek, Roman, and Islamic sources. In A.D. 77, the Greek surgeon Dioscorides published De Materia Medica, a catalog of about 600 plants found in the Mediterranean. This illustrated herbal, which influenced scholars through the Middle Ages, contained information on how and when each plant was gathered, its use by the Greeks, and whether or not it was edible. (Dioscorides even provided recipes.) He also assessed the economic potential of these plants.

However, the systematic study of plants was not confined to the West: the earliest known herbal was compiled by Chinese emperor Shen Nung sometime before 2000 B.C.E., and both the Incas of South America and the Aztecs of Mesoamerica maintained botanical gardens.

The Renaissance in Europe saw a revival of interest in ethnobotany, which was intensified by geographic exploration and later colonialism. In 1542, Renaissance artist Leonhart Fuchs published ‘’De Historia Stirpium,’’ a catalogue of 400 plants native to Germany and Austria. John Ray (1686-1704) provided the first definition of "species" in his ‘’Historia Plantarum’’. John Gerard (1597) – most pop of 16th c. herbals – remained in print for over 400 years.

In 1753, the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus wrote "Species Plantarum", which included information on approximately 5,900 plants. Linnaeus, "the father of taxonomy," is famous for inventing the binomial method of nomenclature, in which all living organisms are assigned a two-part name (genus, species).

The 19th century saw the peak of botanical exploration. Alexander von Humboldt collected data from “the New World,” and the famous Captain Cook brought back information on plants from the South Pacific. At this time, major botanical gardens were founded in Europe, such as the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (commonly known as Kew Gardens).

The field of "aboriginal botany", which studied the forms of plant-life used by aboriginal peoples, emerged in part out of research concentrated in the North American West. Edward Palmer collected artifacts and botanical specimens from peoples in the Great Basin region and Mexico from the 1860s to the 1890s. Other scholars analyzed the uses of plants under an indigenous/local perspective in the early 20th century: e.g. Matilda Coxe Stevenson, Zuni plants (1915); Frank Cushing, Zuni foods (1920); and the team approach of Wilfred Robbins, JP Harrington, and Barbara Freire-Marreco, Tewa pueblo plants (1916).

Modern ethnobotany

Beginning in the 20th century, the field of ethnobotany experienced a shift from the raw compilation of data to a greater methodological and conceptual reorientation. Today, the practice of ethnobotany requires a variety of skills:

- botanical training for the identification and preservation of plant specimens;

- anthropological training to understand the cultural concepts around the perception of plants; and

- linguistic training to transcribe local terms and understand native morphology, syntax, and semantics.

Ethnobotanists engage in a broad array of research questions and practices, which do not lend themselves to easy categorization. However, the following headings attempt to describe some of the key areas of modern study:

Ethnomedicine

Ethnomedicine is a sub-field of medical anthropology that deals with the study of traditional medicines: not only those that have relevant written sources (e.g. Traditional Chinese Medicine, Ayurveda), but especially those whose knowledge and practices have been orally transmitted over the centuries.

In the scientific arena, ethnomedical studies are generally characterized by a strong anthropological approach more than a bio-medical one. The focus of these studies is the perception and context of use of traditional medicines, and not their bio-evaluation.

Reserpine example

Agriculture

Folk Classification

account of behavior is a description of behavior in terms meaningful (consciously or unconsciously) to the actor. Scientists interested in the local construction of meaning, and local rules for behavior, will rely on emic accounts;

The first individual to study the ‘’emic’’ perspective of the plant world was Leopold Glueck, a German physician working in Sarajevo. His 1896 publication on the traditional medicinal uses of plants by rural people in Bosnia may be considered the first modern ethnobotanical work.

Plants in religion, art, and xyz

Richard Evans Schultes' (January 12, 1915 – April 10, 2001) may be considered the father of modern ethnobotany, not only in his devotion to the study of native uses of entheogenic or hallucinogenic plants, especially in the Amazon. He the ritual use of peyote cactus among the Kiowa of Oklahoma, as well as his discovery of the lost identity of the Mexican hallucinogenic plants teonanácatl (various mushrooms belonging to the Psilocybe genus) and ololiuqui (a morning glory species) in Oaxaca, Mexico. Schultes's botanical fieldwork among Native American communities led him to be one of the first to alert the world about destruction of the Amazon rainforest and the disappearance of its native people. He collected over 24,000 herbarium specimens and published numerous ethnobotanical discoveries including the source of the dart poison known as curare, now commonly employed as a muscle relaxant during surgery.

Related fields

Ethnobotany is considered a branch of ethnobiology. Ethnobiology is the study of the past and present interrelationships between human cultures and the plants, animals, and other organisms in their environment, including relationships with ecosystems as a whole. The term ethnobiology did not come into use until the twentieth century (Sillitoe, 2006). It was originally and is still being referred to as biological anthropology by many scholars in related disciplines. However, unlike the traditional biological anthropology, which primarily studies humans and the nonhuman primates as biological organisms, ethnobiology is wider in scope, both in academic and practical aspects. Most importantly, ethnobiology makes apparent the academic connection between human cultural practices and subdisciplines of biology. Ethnobiology is an interdisciplinary subject which draws on knowledge from many different fields of knowledge such as linguistics, anthropology, biology, and chemistry. The principal disciplines of enthnobiology include ethnobotany, ethnozoology, and ethnoecology.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alexiades, M. & J. Wood Sheldon, Eds. 1996. Selected Guidelines for Ethnobotanical Research: A Field Manual. New York, NY: New York Botanical Garden Press.

- Balick, M.J. & P.A. Cox. 1996. Plants, People, and Culture: The Science of Ethnobotany. New York, NY: Scientific American Library.

- Cotton, C.M. 1996. Ethnobotany: Principles and Applications. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

- Harrison, K.D. 2006. When Languages Die: The Extinction of the World's Languages and the Erosion of Human Knowledge. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Martin, G.J. 2004. Ethnobotany: A Methods Manual. London, UK: Earthscan.

- Minnis, P.E., Ed. 2000. Ethnobotany: A Reader. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

External links

- Society for Economic Botany

- International Society of Ethnobiology

- Society of Ethnobiology

- General Information on Ethnobotany and Ethnomedicine

- Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine

- Journal of Ethnobotany Research and Applications

- "Before Warm Springs Dam: History of Lake Sonoma Area" This California study has information about one of the first ethnobotanical mitigation projects undertaken in the USA.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.