Ernst Haeckel

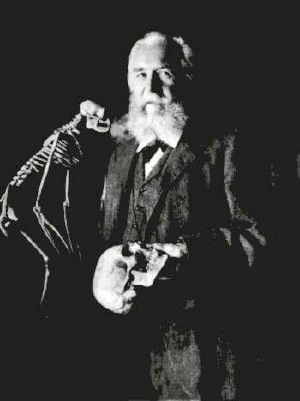

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (February 16, 1834 — August 9, 1919), also written von Haeckel, was an eminent German biologist, naturalist, philosopher, physician, professor and artist.

Ernst Haeckel named thousands of new species (see below), mapped a genealogical tree relating all life forms, and coined many terms in biology, including phylum, phylogeny and ecology. He also discovered many species in the the kingdom he named Protista (details below).

Haeckel promoted Charles Darwin's work in Germany and developed the controversial "recapitulation theory" claiming that an individual organism's biological development, or ontogeny, parallels and summarizes its species' entire evolutionary development, or phylogeny: "ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny" (see below).

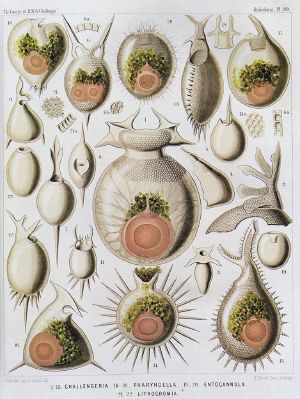

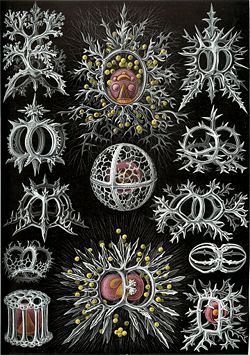

The published artwork of Haeckel includes over 100 detailed, multi-color illustrations of animals and sea creatures (see: Kunstformen der Natur, "Artforms of Nature"). As a philosopher, Ernst Haeckel wrote Die Welträthsel (1895-1899, in English, The Riddle of the Universe, 1901), the genesis for the term "world riddle" (Welträthsel); and Freedom in Science and Teaching (1877, English 1879, ISBN 1-4102-1175-4) to support teaching evolution.

Kunstformen der Natur (Art Forms of Nature) is a book of lithographic and autotype prints by German biologist Ernst Haeckel. Originally published in sets of ten between 1899 and 1904 and as a complete volume in 1904, it consists of 100 prints of various organisms, many of which were first described by Haeckel himself. Over the course of his career, over 1000 engravings were produced based on Haeckel's sketches and watercolors; many of the best of these were chosen for Kunstformen der Natur, translated from sketch to print by lithographer Adolf Giltsch.[1]

According to Haeckel scholar Olaf Breidbach (the editor of modern editions of Kunstformen), the work was "not just a book of illustrations but also the summation of his view of the world." The over-riding themes of the Kunstformen plates are symmetry and organization. The subjects were selected to embody organization, from the scale patterns of boxfishes to the spirals of ammonites to the perfect symmetries of jellies and microorganisms, while images composing each plate are arranged for maximum visual impact.[2]

Among the notable prints are numerous radiolarians, which Haeckel helped to popularize among amateur microscopists; at least one example is found in almost every set of 10.

Kunstformen der Natur was influential in early 20th century art, architecture, and design, bridging the gap between science and art. In particular, many artists associated with Art Nouveau were influenced by Haeckel's images, including René Binet, Karl Blossfeldt, Hans Christiansen, and Émile Gallé. One prominent example is the Amsterdam Commodities Exchange designed by Hendrik Petrus Berlage, which was in part inspired by Kunstformen illustrations.[3]

A second edition of Kunstformen, containing only 30 of the prints, was produced in 1924.

Haeckel's ideas and impact

Haeckel was a zoologist, an accomplished artist and illustrator, and later a professor of comparative anatomy. He was one of the first to consider psychology as a branch of physiology. He also proposed many now ubiquitous terms including "phylum" and "ecology." His chief interests lay in evolution and life development processes in general, including development of nonrandom form, which culminated in the beautifully illustrated Kunstformen der Natur (Art forms of nature).

Recapitulation theory

Haeckel advanced the "recapitulation theory" which proposed a link between ontogeny (development of form) and phylogeny (evolutionary descent), summed up in the phrase "ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny". He supported the theory with embryo drawings that have since been shown to be oversimplified and in part inaccurate, and the theory is now considered an oversimplification of quite complicated relationships. It is thought by some critics of Haeckel, particularly creationists, that Haeckel deliberately faked the images to get more support for his ideas. Haeckel introduced the concept of "heterochrony", which is the change in timing of embryonic development over the course of evolution.

Haeckel was also known for his "biogenic theory", in which he suggested that the development of races paralleled the development of individuals. He advocated the idea that "primitive" races were in their infancies and needed the "supervision" and "protection" of more "mature" societies.

Monist philosophy

Haeckel extrapolated a new religion or philosophy called "monism" from evolutionary science. In Haeckel's view of monism, which postulates that all aspects of the world form an essential unity, all economics, politics, and ethics are reduced to "applied biology." [4] Haeckel's writings and lectures on monism were later used to provide scientific (or quasi-scientific) justifications for racism, nationalism, and social Darwinism.[4]

The theory of recapitulation, also called the biogenetic law or ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny, is a theory in biology which attempts to explain apparent similarities between humans and other animals. First espoused in 1866 by German zoologist Ernst Haeckel, a contemporary of Charles Darwin, the theory has been discredited in its absolute form ("strong recapitulation"), although recognized as being perhaps partly fruitful. In biology, ontogeny is the embryonal development process of a certain species, and phylogeny a species' evolutionary history. Observers have noted various connections between phylogeny and ontogeny, explained them with evolutionary theory and taken them as supporting evidence for that theory.

Ontogeny is the growth (size change) and development (shape change) of an individual organism; phylogeny is the evolutionary history of a species. Haeckel's recapitulation theory claims that the development of the individual of every species fully repeats the evolutionary development of that species. Otherwise put, each successive stage in the development of an individual represents one of the adult forms that appeared in its evolutionary history. Haeckel formulated his theory as such: "Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny". This notion later became simply known as recapitulation.

Haeckel produced several embryo drawings that often overemphasized similarities between embryos of related species. These found their ways into many biology textbooks, and into popular knowledge.

For example, Haeckel believed that the human embryo with gill slits (pharyngeal arches) in the neck not only signified a fishlike ancestor, but represented an adult "fishlike" developmental stage. Embryonic pharyngeal arches are not gills and do not carry out the same function. They are the invaginations between the gill pouches or pharyngeal pouches, and they open the pharynx to the outside. Gill pouches appear in all tetrapod animal embryos. In mammals, the first gill bar (in the first gill pouch) develops into the lower jaw (Meckel's cartilage), the malleus and the stapes. In a later stage, all gill slits close, with only the ear opening remaining open. For a technical discussion on the topic, see [1].

Modern biology rejects the literal and universal form of Haeckel's theory. Although humans share ancestors with many other taxa (roughly, fish through reptiles to mammals), stages of human embryonic development are not functionally equivalent to the adults of these shared common ancestors. In other words, no cleanly defined and functional "fish", "reptile" and "mammal" stages of human embryonal development can be discerned. Moreover, development is nonlinear. For example, during kidney development, at one given time, the anterior region of the kidney is less developed (nephridium) than the posterior region (nephron).

The fact that contemporary biologists reject the literal or universal form of recapitulation theory has sometimes been used as an argument against evolution by some creationists. The argument is: "Haeckel's hypothesis was presented as supporting evidence for evolution, Haeckel's theory is wrong, therefore evolution has less support". This argument is not only an oversimplification but misleading because modern biology does recognize numerous connections between ontogeny and phylogeny, explains them using evolutionary theory without recourse to Haeckel's specific views, and considers them as supporting evidence for that theory.

Unfortunately, some older editions of textbooks in the United States still erroneously cite recapitulation theory or the Haeckel drawings as evidence in support of evolution without appropriately explaining them as being misleading or outdated.

Although Haeckel's specific form of recapitulation theory is now discredited among biologists, it did have a strong impact in social and educational theories of the late 19th century.

English philosopher Herbert Spencer was one of the most energetic promoters of evolutionary ideas to explain pretty well everything in sight; He compactly expressed the basis for a cultural recapitulation theory of education in the following claim:[5]

If there be an order in which the human race has mastered its various kinds of knowledge, there will arise in every child an aptitude to acquire these kinds of knowledge in the same order.... Education is a repetition of civilization in little.

The maturationist theory of G. Stanley Hall was based on the premise that growing children would recapitulate evolutionary stages of development as they grew up and that there was a one-to-one correspondence between childhood stages and evolutionary history, and that it was counterproductive to push a child ahead of its development stage. The whole notion fit nicely with other social Darwinist concepts, such as the idea that "primitive" societies needed guidance by more advanced societies, i.e. Europe and North America, which were considered by social Darwinists as the pinnacle of evolution. An early form of the law was devised by the 19th-century Estonian zoologist Karl Ernst von Baer, who observed that embryos resemble the embryos, but not the adults, of other species.

Haeckel's influence

Although Haeckel's ideas are important to the history of evolutionary theory, and he was a competent invertebrate anatomist most famous for his work on radiolaria, many speculative concepts that he championed are now considered incorrect. For example, Haeckel described and named hypothetical ancestral microorganisms that have never been found. His concept of recapitulation has been disputed in the form he gave it (now called "strong recapitulation"). Haeckel did not support natural selection, rather believing in a Lamarckian inheritance of acquired characteristics (Darwin considered both of these paths for evolution viable). [7] It has also been claimed (Richardson 1998) that Haeckel's drawings of 1874 were substantially fabricated; [8] [9] however, it was later claimed that "there is evidence of sleight of hand" on both sides of the feud between Haeckel and Wilhelm His (Richardson & Keuck 2001).[9] There were multiple versions of the embryos drawings, and Haeckel himself rejected the claims of fraud.[9] [10] The controversy involves several different issues (see more details at: recapitulation theory).

Although best known for "recapitulation theory" with the famous dictum "ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny," Haeckel also coined many words commonly used by biologists today, such as phylum, phylogeny, ecology ("oekologie"),[11] and proposed the kingdom Protista.[12]

Haeckel also stated that "politics is applied biology",[4] a quote used by various Nazis. The Nazi party used not only Haeckel's quotations, but also Haeckel's broader philosophy of "Monism," which they used as justification for racism, nationalism and social Darwinism.[4]

In 1909, Haeckel retired from teaching, and in 1910 he withdrew from the Evangelist church.[12] Haeckel's wife, Agnes, died in 1915, and Ernst Haeckel became substantially more frail, with a broken leg (thigh) and broken arm.[12] He sold the mansion Medusa ("Villa Medusa") in 1918 to the Carl Zeiss foundation.[12] Ernst Haeckel died on August 9, 1919.

The Ernst Haeckel house ("Villa Medusa") in Jena, Germany contains a historic library.

Biography

Ernst Haeckel was born on February 16, 1834, in Potsdam (then part of Prussia). [12] In 1852, Haeckel completed studies at Cathedral High School (Domgymnasium) of Mersburg.[12] He then studied medicine in Berlin, particularly with Albert von Kölliker, Franz Leydig, Rudolf Virchow (with whom he later worked briefly as assistant), and with anatomist-physiologist Johannes Müller/Mueller (1801-1858).[12] In 1857, Haeckel attained a doctorate in medicine (M.D.), and afterwards he received a license to practice medicine. The occupation of physician appeared less worthwhile to Haeckel, after contact with suffering patients.[12]

Haeckel studied under Carl Gegenbaur at the University of Jena for three years, earning a doctorate in zoology,[12] before becoming a professor of comparative anatomy at the University of Jena, where he remained 47 years, from 1862-1909. Between 1859 and 1866, Haeckel worked on many "invertebrate" groups, including radiolarians, poriferans (sea sponges) and annelids (segmented worms).[4] During a trip to the Mediterranean, Haeckel named nearly 150 new species of radiolarians.[4] "Invertebrates" provided the data for most of his experimental work on evolutionary development, leading to his "law of recapitulation." [4] Haeckel named thousands of new species from 1859 to 1887. [11]

Radiolarians (also radiolaria) are amoeboid protozoa that produce intricate mineral skeletons, typically with a central capsule dividing the cell into inner and outer portions, called endoplasm and ectoplasm. They are found as zooplankton throughout the ocean, and because of their rapid turn-over of species, their tests are important diagnostic fossils found from the Cambrian onwards. Some common radiolarian fossils include Actinomma, Heliosphaera and Hexadoridium.

German biologist Ernst Haeckel produced exquisite (and perhaps somewhat exaggerated) drawings of radiolaria, helping to popularize these protists among Victorian parlor microscopists alongside foraminifera and diatoms.

Haeckel was also a free-thinker who went beyond biological studies, dabbling in anthropology, psychology, and cosmology.[4] Haeckel's speculative ideas and possible fudging of data or diagrams, plus the lack of empirical support for many of his ideas, have tarnished his scientific credentials; however, Ernst Haeckel remained a very popular figure in Germany and was considered a hero by many of his countrymen.[4]

Haeckel was a flamboyant figure. He sometimes took great (and non-scientific) leaps from available evidence. For example, at the time that Darwin first published On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection (1859), no remains of human ancestors had yet been found. Haeckel postulated that evidence of human evolution would be found in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), and described these theoretical remains in great detail. He even named the as-of-yet unfound species, Pithecanthropus alalus, and charged his students to go find it. (Richard and Oskar Hertwig were two of Haeckel´s many important students.)

Works

Haeckel's literary output was extensive, working as a professor at the University of Jena for 47 years, and even at the time of the celebration of his sixtieth birthday at Jena in 1894, Haeckel had produced 42 works with nearly 13,000 pages, besides numerous scientific memoirs and illustrations.

Selected Monographs

'Radiolaria (1862), Siphonophora (1869), Monera (1870) and Calcareous Sponges (1872), as well as several Challenger reports: Deep-Sea Medusae (1881), Siphonophora (1888), Deep-Sea Keratosa (1889), and another Radiolaria (1887), the last being illustrated with 140 plates and enumerating over four thousand (4000) new species.[13]

Selected Published Works

- 1866:General Morphology

- 1868: Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte (1868, in English, The Natural History of Creation reprinted 1883)

- 1874:Anthropogenie

- 1877:Freie Wissenschaft und freie Lehre (1877, in English, Freedom in Science and Teaching) in reply to a speech in which Virchow objected to the teaching of evolution in schools, on the grounds that evolution was an unproven hypothesis;[13]

- 1894:Die systematische Phylogenie (1894, "Systematic Phylogeny")

- 1895-1899:Die Welträthsel (1895-1899, also spelled Die Welträtsel ("world-riddle"), in English The Riddle of the Universe, 1901);[13]

- 1898:Über unsere gegenwärtige Kenntnis vom Ursprung des Menschen (1898, translated into English as The Last Link, 1908)

- 1904:Kunstformen der Natur (1904, Artforms of Nature), with plates representing detailed marine animal forms

- 1905:Der Kampf um den Entwickelungsgedanken (1905, English version, Last Words on Evolution, 1906)

- 1905:Wanderbilder (1905, "travel images"), with reproductions of his oil-paintings and water-color landscapes.[13]

Notes

- ↑ Breidbach, Visions of Nature, pp 253

- ↑ Breidbach, Visions of Nature, pp 229-231

- ↑ Breidbach, Visions of Nature, pp 231, 268-269

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 "Ernst Haeckel" (biography), UC Berkeley, 2004, webpage: BerkeleyEdu-Haeckel.

- ↑ Kieran Egan, The educated mind: How Cognitive Tools Shape Our Understanding., p.27 (University of Chicago Press, 1997, Chicago. ISBN 0-226-19036-6)

- ↑ Herbert Spencer (1861). Education, p.5.

- ↑ Ruse, M. 1979. The Darwinian Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Michael K. Richardson. 1998. "Haeckel's embryos continued." Science 281:1289, quoted in NaturalScience.com webpage Re: Ontogeny and phylogeny: A Letter from Richard Bassetti; Editor's note.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 "Haeckel's embryos" (of drawings, with detailed quotes by Haeckel & others), Tony Britain, 2001, AntiEvolution.org webpage: AE-myths.

- ↑ "The Controversy over Evolution in Biology Textbooks" (Texas, Textbooks and Evolution), Dr. Raymond G. Bohlin (President), Probe Ministries, 2003, Probe.org webpage: ProbeOrg-Textbook-Controversy: mentions Haeckel drawings, peppered moth story and Cambrian explosion.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Rudolf Steiner and Ernst Haeckel" (colleagues), Daniel Hindes, 2005, DefendingSteiner.com webpage: Steiner-Haeckel.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 12.8 "Ernst Haeckel" (article), German Wikipedia, October 26, 2006, webpage: DE-Wiki-Ernst-Haeckel: last paragraph of "Leben" (Life) section.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedHa1911

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Charles Darwin (1859). On the Origin of Species (by Means of Natural Selection). London: John Murray.

- Charles Darwin (2003 edition). The Origin of Species (with introduction by Julian Huxley). Signet Classics. ISBN 0-451-52906-5.

- Ernst Haeckel, Freedom in Science and Teaching (1879), reprint edition, University Press of the Pacific, February 2004, paperback, 156 pages, ISBN 1-4102-1175-4.

- Ernst Haeckel, The History of Creation (1868), translated by E. Ray Lankester, Kegan Paul, Trench & Co., London, 1883, 3rd edition, Volume 1.

- Ernst Haeckel, Kunstformen der Natur ("Artforms of Nature"), 1904, (from series published 1899-1904): over 100 detailed, multi-color illustrations of animals and sea creatures.

- Ernst Haeckel, The Riddle of the Universe (Die Weltraetsel, 1895-1899), Publisher: Prometheus Books, Buffalo, NY, 1992, reprint edition, paperback, 405 pages, illustrated, ISBN 0-87975-746-9.

- Richard Milner, The Encyclopedia of Evolution: Humanity's Search for Its Origins, Henry Holt, 1993.

- Michael K. Richardson, "Haeckel's embryos continued" (article), Science Volume 281:1289, 1998.

- Richardson, M. K. & Keuck, G. (2001) "A question of intent: when is a 'schematic' illustration a fraud?," Nature 410:144 (vol. 410, no. 6825, page 144), March 8, 2001.

- M. Ruse, The Darwinian Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979.

External links

- Marine Biological Laboratory Library - An exhibition of material on Haeckel, including background on many Kunsformen der Natur plates

- University of California, Berkeley - Ernst Haeckel biography

- Ernst Haeckel – Evolution's controversial artist. A slide-show essay about Ernst Haeckel.

- Kunstformen der Natur, Wikimedia Commons: over 100 detailed animal drawings.

- Kunstformen der Natur, scanned (from biolib.de Stuebers Online Library)

- PNG alpha-transparencies of Haeckel's "Kustformen der natur"

- Proteus - An animated documentary film on the life and work of Ernst Haeckel

- Ernst Haeckel Haus and Ernst Haeckel Museum in Jena

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.