Box jellyfish

| Box Jellyfish | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

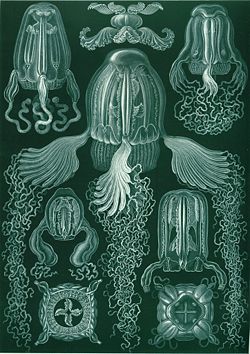

"Cubomedusae," from Ernst Haeckel's Kunstformen der Natur, 1904

| ||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||

| ||||||||

|

see text |

Box jellyfish is the common name for any of the radially symmetrical, marine invertebrates comprising the Cnidarian class Cubozoa, characterized by generally well-developed eyes and a life cycle dominated by a cube-shaped medusae. The name sea wasp is also applied to some species of cubozoans, including the well-known Chironex fleckeri, which is sometimes called the box jellyfish and is among the most venomous creatures in the world. Members of Cubozoa, collectively, are also known scientifically as cubazoans and commonly as box jellies.

Box jellies are important components of marine ecosystems, capturing and eating fish, crustaceans, and worms, and despite their barbed and poisoned nematocysts, being eaten by large fish and sea turtles. While they can be highly dangerous to those swimmers, divers, and surfers in their habitat, but their unique form and behavior adds to the wonder and mystery of nature for people as well.

Overview and description

Box jellyfish are classified within Cnidaria, a phylum containing relatively simple invertebrate animals found exclusively in aquatic, mostly marine, environments. Cniderians include corals, sea anemones, jellyfish, sea pens, sea pansies, and sea wasps, as well as tiny freshwater hydra. The name of the phylum comes from cnidocytes, which are specialized cells that carry stinging "organelles" (really specialized secretory products).

The box jellyfish comprise one of four main classes of Cnidaria:

- Class Anthozoa (anemones, sea fans, corals, among others)

- Class Hydrozoa (Portuguese Man o' War, Obelia, and more)

- Class Scyphozoa (true jellyfish)

- Class Cubozoa (box jellies)

Theoretically, members of Cnidaria have life cycles that alternate between asexual polyps (the body as a vase shaped form), and sexual, free-swimming forms called medusae (singular medusa; the body in a bell-shaped form). In reality, the class Anthozoa is characterized by the absence of medusae, living only as polyps, while Scyphozoa live most of their life cycle as medusa. The Hydrozoa live as polyps, medusae, and species that alternate between the two (Towle 1989). In most taxa of Hydrozoa, the polyp is the most persistent and conspicuous stage, but some lack the medusa phase, and others lack the polyp phase (Fautin and Romano 1997).

Invertebrates belonging to the class Cubozoa have a life cycle dominated by the medusa, which appears cube or square shaped, when viewed from above. Members of Cubozoa, Hydrozoa, and Scyphozoa are sometimes grouped together as "Medusozoa" because a medusa phase is present in all three (Fautin and Romano 1997).

The cubozoan body is a bell that is square in horizontal cross section, with the mouth and manubrium inside the bell. On the underside of the bell is a flap of tissue called the velarium, and muscular fleshy pads termed pedalia are found at the corners of the bell, with one or more tentacles connected to each pedalium. Four sensory structures called rhopalia are located midway between the pedalia on the bell. Box jellyfish have eyes, which are surprisingly complex, including regions with lenses, corneas, and retinas; however, they do not have a brain, so how the images are interpreted remains unknown. Like all cnidarians, box jellyfish possess stinging cells that can fire a barb and transfer venom (Waggoner and Collins 2000).

Cubozoans are agile and active swimmers, unlike the more planktonic jellyfish. They have been commonly observed to swim a meter in just five to ten seconds, and there are unconfirmed reports of large specimens of Chironex fleckeri swimming as fast as two meters in one second (Waggoner and Collins 2000).

Box jellies can be found in many tropical areas, including near Australia, the Philippines, Hawaii, and Vietnam.

Defense and feeding mechanisms

Cnidarians take their name from a specialized cell, the cnidocyte (nettle cell). The cnida or nematocyst is secreted by the Golgi apparatus of a cell and is technically not an organelle but "the most complex secretory product known" (Waggoner and Collins 2000). Tentacles surrounding the mouth contain nematocysts. The nematocysts are the cnidarians' main form of offense or defense and function by a chemical or physical trigger that causes the specialized cell to eject a barbed and poisoned hook that can stick into, ensnare, or entangle prey or predators, killing or at least paralyzing its victim.

Box jellyfish are voracious predators and are known to eat fish, crustacean arthropods, and worms, utilizing the tentacles and nematocysts (Waggoner and Collins 2000). When the tentacles contact the prey, the nematocysts fire into the prey, with the barbs holding onto the prey and transferring venom. The tentacles then contract and pull the prey near the bell, where the muscular pedalium pushes the tentacle and prey into the bell of the medusa, and the manubrium reaches out for the prey and mouth engulfs it (Waggoner and Collins 2000).

Box jellies use the powerful venom contained in epidermic nematocysts to both stun or kill their prey prior to ingestion and as an instrument for defense. Their venom is the most deadly in the animal kingdom and by 1996, had caused at least 5,567 recorded deaths since 1954 (Williamson et al., 1996). Most often, these fatal envenomations are perpetrated by the largest species of box jelly, Chironex fleckeri, owing to its high concentration of nematocysts, though at least two deaths in Australia have been attributed to the thumbnail-sized irukandji jellyfish (Carukia barnesi) (Fenner and Hdok 2002). Those who fall victim to Carukia barnesi suffer several severe symptoms known as Irukandji syndrome (Little and Mulcahy 1998). The venom of cubozoans is very distinct from that of scyphozoans. Sea turtles, however, are apparently unaffected by the sting and eat box jellies.

While Chironex fleckeri and the Carukia barnesi (Irukandji) species are the most venomous creatures in the world, with stings from such species excruciatingly painful and often fatal, not all species of box jellyfish are this dangerous to humans (Williamson 1996).

Some theorize box jellyfish actively hunt their prey—for effective hunting they move extremely quickly instead of drifting as do true jellyfish.

Box jellyfish are abundant in the warm waters of northern Australia and drive away most swimmers. However, they generally disappear during the Australian winter. Australian researchers have used ultrasonic tagging to learn that these creatures sleep on the ocean floor between 3 A.M. and dawn. It is believed that they sleep to conserve energy and to avoid predators.

Vision

Box jellyfish are known to be the only jellyfish with an active visual system, consisting of multiple eyes located on the center of each side of its bell.

The eyes occur in clusters on the four sides of the cube-like body, in the four sensory structures called rhopalia. Each rhopalia have six sensory spots, giving 24 sensory structures (or eyes) in total. Sixteen are simply pits of light-sensitive pigment (eight slit-shaped eyes and eight lens-less pit eyes), but one pair in each cluster is surprisingly complex, with a sophisticated lens, retina, iris, and cornea, all in an eye only 0.1 millimeters across.

The lenses on these eyes have been analyzed and could form distortion free images. Despite the perfection of the lenses, the retinas of the eyes lie closer to the lens than the optimum focal distance, resulting in a blurred image. One of these eyes in each set has an iris that contracts in bright light. Four of the eyes can only make out simple light levels.

It is not currently known how this visual information is processed by Cubozoa, as they lack a central nervous system, although they seem to have four brain-like organs (Nilsson et al. 2005). Some scientists have proposed that jellies have a “nerve net” that would allow procession of visual cues.

Classification

There are two main taxa of cubozoans, Chirodropidae and Carybdeidae, containing 19 known, extant species between them. The chirodropids and carybdeids are easy to distinguish morphologically. Carybdeidae, which contains the Carukia barnesi (Irukandji) species, generally have only a single tentacle trailing from each corner of their bells, with each tentacle connected to a single pedalium at each corner. However, in species of Tripedalia, while each tentacle likewise is connected to a single pedalium, there are two or three pedalia on each corner of the bell, giving two or three tentacles trailing from each corner (Waggoner and Collins 2000). Box jellyfish of the Chirodropidae group, which contains the Chironex fleckeri species, are distinguished by always having four pedalia, one at each corner, with each of the pedalia having multiple tentacles (Waggoner and Collins 2000). In other words, chirodropids have multiple tentacles connected to each pedalium, while carybdeids always have just one tentacle per pedalium (Waggoner and Collins 2000).

The following is a taxonomic scheme for the cubozoans, with Chirodropidae and Carybdeidae classified as families, and recognizing 9 genera:

- Phylum Cnidaria

- Family Chirodropidae

- Chironex fleckeri

- Chirosoides buitendijkl

- Chirodropus gorilla

- Chirodropus palmatus

- Chiropsalmus zygonema

- Chiropsalmus quadrigatus

- Chiropsalmus quadrumanus

- Family Carybdeidae

- Carukia barnesi

- Manokia stiasnyi

- Tripedalia binata

- Tripedalia cystophora

- Tamoya haplonema

- Tamoya gargantua

- Carybdea alata

- Carybdea xaymacana

- Carybdea sivicksi

- Carybdea rastonii

- Carybdea marsupialis

- Carybdea aurifera

The Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS 2005a) recognizes two orders, three families, nine genera, and 19 species. The two orders are Carybdeida and Chirodropida. Within Carybdeida, ITIS (2005b) recognizes the family Carybdeidae. However, within Chirodropida, ITIS (2005c) recognizes two families, Chirodropidae and Chiropsalmidae. Within the family Carybdeidae, recognized are the genera Carybdea (6 species), Tamoya (2 species), and Tripedalia (1 species) (ITIS 2005b). Within the family Chirodropidae are recognized the genera Chirodectes (1 species), Chirodropus (2 species), and Chironex (1 species), while within the family Chiropsalmidae are recognized the genera Chiropsalmus (3 species), Chiropsella (1 species), and Chiropsoides (2 species) (ITIS 2005c).

Treatment of stings

First aid

If swimming at a beach where box jellies are known to be present, a bottle of vinegar is an extremely useful addition to the first aid kit. Following a sting, vinegar should be applied for a minimum of 30 seconds (Fenner et al. 1989). Acetic acid, found in vinegar, disables the box jelly's nematocysts that have not yet discharged into the bloodstream (though it will not alleviate the pain). Vinegar may also be applied to adherent tentacles, which should then be removed immediately; this should be done with the use of a towel or glove to avoid bringing the tentacles into further contact with the skin. These tentacles will still sting if separate from the bell, or if the creature is dead. Removing the tentacles without first applying vinegar may cause unfired nematocysts to come into contact with the skin and fire, resulting in a greater degree of envenomation. If no vinegar is available, a heat pack has been proven for moderate pain relief. However, careful removal of the tentacles by hand is recommended (Hartwick et al. 1980). Vinegar has helped save dozens of lives on Australian beaches.

Although commonly recommended in folklore and even some papers on sting treatment (Zoltan et al. 2005), there is no scientific evidence that urine, ammonia, meat tenderizer, sodium bicarbonate, boric acid, lemon juice, freshwater, steroid cream, alcohol, coldpack, or papaya will disable further stinging, and these substances may even hasten the release of venom (Fenner 2000).

Pressure immobilization bandages, methylated spirits, or vodka should be used for jelly stings (Hartwick et al. 1980; Seymour et al. 2002). Often in severe Chironex fleckeri stings cardiac arrest occurs quickly, so Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) can be life saving and takes priority over all other treatment options (including application of vinegar). The emergency medical system should be activated for immediate transport to the hospital.

Prevention of stings

Pantyhose, or tights, were once worn by Australian lifeguards to prevent stings. These have now been replaced by lycra stinger suits. Some popular recreational beaches erect enclosures (stinger nets) offshore to keep predators out, though smaller species such as Carukia barnesi (Irukandji Jellyfish) can still filter through the net (Nagami 2004).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Fautin, D.G., and S.L. Romano. 1997. Cnidaria. Sea anemones, corals, jellyfish, sea pens, hydra. Tree of Life web project, Version 24, April 1997. Retrieved May 24, 2008.

- Fenner, P. 2000. Marine envenomation: An update—A presentation on the current status of marine envenomation first aid and medical treatments. Emerg Med Australas 12(4): 295-302. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- Fenner, P., and J. Hadok. 2002. Fatal envenomation by jellyfish causing Irukandji syndrome. Med J Aust 177(7): 362-3. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- Fenner, P., J. Williamson, and J. Blenkin. 1989. Successful use of Chironex antivenom by members of the Queensland Ambulance Transport Brigade. Med J Aust 151(11-12): 708-10. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- Hartwick, R., V. Callanan, and J. Williamson. 1980. Disarming the box-jellyfish: Nematocyst inhibition in Chironex fleckeri. Med J Aust 1(1): 15-20.

- Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS). 2005a. Cubozoa. ITIS Taxonomic Serial No.: 51449. Retrieved May 24, 2008.

- Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS). 2005b. Carybdeida Claus, 1886. ITIS Taxonomic Serial No.: 718929. Retrieved May 24, 2008.

- Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS). 2005c. Chirodropida Haeckel, 1880. ITIS Taxonomic Serial No.: 718932. Retrieved May 24, 2008.

- Little, M., and R. Mulcahy. 1998. A year's experience of Irukandji envenomation in far north Queensland. Med J Aust 169(11-12): 638-41. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- Nagami, P. 2004. Bitten: True Medical Stories of Bites and Stings. St. Martin's Press, 54. ISBN 0312318227.

- Nilsson, D. E., L. Gislén, M. M. Coates, et al. 2005. Advanced optics in a jellyfish eye. Nature 435: 201-205. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- Seymour, J., T. Carrette, P. Cullen, M. Little, R. Mulcahy, an P. Pereira. 2002. The use of pressure immobilization bandages in the first aid management of cubozoan envenomings. Toxicon 40(10): 1503-5. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- Towle, A. 1989. Modern Biology. Austin, TX: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 0030139198.

- Waggoner, B., and A.G. Collins. 2000. Introduction to Cubozoa: The box jellies! University of California Museum of Paleontology'. Retrieved May 24, 2008.

- Williamson, J. A., P. J. Fenner, J. W. Burnett, and J. Rifkin. 1996. Venomous and Poisonous Marine Animals: A Medical and Biological Handbook. Surf Life Saving Australia and University of New South Wales Press. ISBN 0868402796.

- Zoltan, T., K. Taylor, and S. Achar. 2005. Health issues for surfers. Am Fam Physician 71(12): 2313-7. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

External links

- Box jellyfish facts. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- ThinkQuest: Box jellyfish, Boxfish, Deadly sea wasp. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- Box Jelly Fish, dangers on the great barrier reef. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.