Book of Jonah

| Books of the |

In the Hebrew Bible, the Book of Jonah is the fifth in a series of books known as the Minor Prophets (itself a subsection of the Nevi’im or Prophets). Unlike other prophetic books however, the Book of Jonah is not primarily a record of prophet’s words. Rather, it tells the story of a reluctant man who resists God's call but ultimately becomes one of the most effective prophets in the entire Bible.

The story is based on an obscure figure that lived during the reign of Jeroboam II (786-746 B.C.E.). In the Hebrew Bible, Jonah son of Amittai is only elsewhere mentioned at II Kings 14:25. The book itself was probably written in the post-exilic period (after 530 B.C.E.) and based on oral traditions that had been passed down from the eighth century B.C.E. Jonah is considered a "minor" prophet because the book was originally written with the other, smaller prophetic books on a single scroll.

The story has an interesting interpretive history (see below) and is one of the most popular children’s stories in the Bible. It is unique among the Old Testament books in that it focuses on an ultimately prophetic ministry to a Gentile city which was one of Israel's most formidable enemies.

Narrative

Summary

The Book of Jonah is almost entirely narrative with the exception of a hymn supposedly written by the prophet in chapter 2, while in the belly of the great fish. The plot centers on a conflict between Jonah and God. God calls Jonah to preach against Jonah, but Jonah resists and attempts to flee. He goes to Joppa and boards a ship bound for Tarshish. God calls up a great storm at sea. The crew casts lots to determine who is responsible for their bad fortune, and Jonah is identified as the man. He admits that the storm has been caused because of God's anger at him and volunteers to be cast overboard in order that the seas will be calmed. After trying unsuccessfully to row to shore, his shipmates beg God not to hold his death against them and cast him into the sea. A huge fish, also sent by God, swallows Jonah. For three days and three nights Jonah languishes inside the fish's belly. Inside the fish, Jonah composes a remarkable hymn of praise for God's mercy:

- In my distress I called to the Lord,

- and he answered me.

- From the depths of the Sheol I called for help,

- and you listened to my cry.

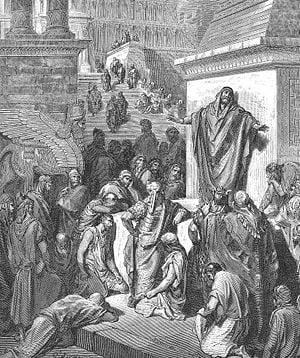

Moved by Jonah's prayer, God commands the fish, which vomits out Jonah safely on dry land. After his rescue, Jonah obeys the call to prophesy against Nineveh. His words a simple: "Forty more days and Nineveh will be overturned." Surprisingly the people of this Gentile city repent. It's king immediately humbles himself and repents, issuing the following decree:

- Do not let any man or beast, herd or flock, taste anything; do not let them eat or drink. But let man and beast be covered with sackcloth. Let everyone call urgently on God. Let them give up their evil ways and their violence. 9 Who knows? God may yet relent and with compassion turn from his fierce anger so that we will not perish. (Jonah 3:7-9)

God indeed repents of his anger, proving that not only Israelites but Gentiles too can count on his compassion if their turn from evil. Jonah, however, is not happy. Rather than seeing his unprecident success in bring a Gentile city to repentance before the God of Israel, he pouts, petulanting complaining to God: "I knew that you are a gracious and compassionate God, slow to anger and abounding in love, a God who relents from sending calamity. Now, O Lord, take away my life, for it is better for me to die than to live." (4:2-3)

The story ends on an ironic, even humorous note, as Jonah retires to the desert to observe what would happen to the city. God causes a plant to grow to shade Jonah from the heat but then sends a worm the next morning to devour the plant. Jonah again complains, saying "It would be better for me to die than to live."

God then shows Jonah that the vine was really only a way of teaching Jonah a lesson. He speaks to his reluctant prophet a final time, saying:

- You had compassion on the plant for which you did not work and which you did not cause to grow, which came up overnight and perished overnight. Should I not have compassion on Nineveh, the great city in which there are more than 120,000 persons who do not know the difference between their right and left hand, as well as many animals?" (4:10-11)

Setting

The story of Jonah is set against the historical background of Ancient Israel in the eighth-seventh centuries B.C.E. and the religious and social issues of the late sixth to fourth centuries B.C.E. The views accurately coincide with the latter chapters of the book of Isaiah (sometimes classified as Third Isaiah), where Israel is given a prominent place in the expansion of God's kingdom to the Gentiles. (These facts have led a number of scholars to believe that the book was actually written in this later period.)

The Jonah mentioned in II Kings 14:25 lived during the reign of Jeroboam II (786-746 B.C.E.) and was from the city of Gath-hepher. This city, modern el-Meshed, located only several miles from Nazareth in what would have been known as the Kingdom of Israel. Nineveh was the capital of the ancient Assyrian empire, which conquered Israel in 722 B.C.E. The book itself calls Nineveh a “great city,” probably referring both to its affluence and its size.

Characters

The story of Jonah is a drama between a passive man and an active God. Jonah, whose name literally means "dove," is introduced to the reader in the very first verse. The name is decisive. While most prophets had heroic names (e.g., Isaiah means "God has saved"), Jonah's name carries with it an element of passivity.

Jonah's passive character then is contrasted with the other main character: God (lit. "I will be what I will be"). God's character is altogether active. While Jonah flees, God pursues. While Jonah falls, God lifts up. The character of God in the story is progressively revealed through the use of irony. In the first part of the book, God is depicted as relentless and wrathful; in the second part of the book, He is revealed to be truly loving and merciful.

The other characters of the story include the sailors in chapter 1 and the people of Nineveh in chapter 3. These characters are also contrasted to Jonah's passivity. While Jonah sleeps in the hull, the sailors pray and try to save the ship from the storm (2:4-6). While Jonah passively finds himself forced to act under the Divine Will, the people of Nineveh actively petition God to change His mind.

Interpretive history

As with many canonical books, the Book of Jonah has had a long and varied interpretive history. This history spans from ancient rabbinic interpretations to "post modern" reader-response interpretations. The interpretative styles of Jews, Christians, Muslims, and atheists have all been employed to understand the story of Jonah. This section will consider how these various groups have interpreted Jonah throughout time.

Early Jewish interpretation

The story of Jonah has numerous theological implications, and Jews have always recognized this. In their early translations of the Hebrew Bible, Jewish translators tended to remove anthropomorphic imagery in order to prevent the reader from misunderstanding the ancient texts. This tendency is evidenced in both the Aramaic translations (i.e. the Targum) and the Greek translations (i.e. the Septuagint). As far as Jonah is concerned, Targum Jonah offers a good example of this.

Targum Jonah

In Jonah 1:6, the Masoretic Text (MT) reads, "...perhaps God will pay heed to us...." This phrase, however, is problematic. Are God's actions dictated by our desires, or our requests? But God, Jews believed, was unchangeable. How could a mere human direct the divine will? So, Targum Jonah translates this passage as: "...perhaps there will be mercy from the Lord upon us...." The captain's proposal was now no longer an attempt to change the divine will; rather, it was an attempt to appeal to divine mercy. Furthermore, in Jonah 3:9, the MT reads, "Who knows, God may turn and relent [lit. repent]?" Yet Targum Jonah translates this as, "Whoever knows that there are sins on his conscience let him repent of them and we will be pitied before the Lord." God does not change his mind; rather God simply fulfills his promise: when His people repent, he will pity them and forgive them.

Dead Sea Scrolls

Among the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS), the book was only found in half of the ten Minor Prophets manuscripts and is not even mentioned among the non-biblical manuscripts (Abegg 443). If scholarly consensus is correct in its assessment that the DSS were the product of the Essenes, this would be no surprise. The book of Jonah not only posed problems for Jews because it tells of God changing His mind, it also demonstrates God’s favor to one of Israel’s gentile enemies.

Early Christian interpretation

New Testament

The earliest Christian interpretations of Jonah are found in the Gospel of Matthew (see Matthew 12:38-42 and 16:1-4) and the Gospel of Luke (see Luke 11:29-32). Both Matthew and Luke record a tradition of Jesus’ interpretation of the story of Jonah (notably, Matthew includes two very similar traditions in chapters 12 and 16). As with most Old Testament interpretations found in the New Testament, Jesus’ interpretation is primarily “typological”. Jonah becomes a “type” for Jesus. Jonah spent three days in the belly of the fish; Jesus will spend three days in the ground. Here, Jesus plays on the imagery of Sheol found in Jonah’s prayer. While Jonah metaphorically declared, “Out of the belly of Sheol I cried,” Jesus will literally be in the belly of Sheol. Finally, Jesus compares his generation to the people of Nineveh. Jesus fulfills his role as a type of Jonah, however his generation fails to fulfill its role as a type of Nineveh. Nineveh repented but his generation, which has seen and heard one even greater than Jonah, fails to repent. Through his typological interpretation of the story of Jonah, Jesus has weighed his generation and found it wanting.

Augustine of Hippo

Contrary to popular belief, the debate over the credibility of the miracle of Jonah is not a modern one. Without a doubt, naturalism and the philosophy of David Hume have impacted modern interpretations of the miraculous story; yet the credibility of a human being surviving in the belly of a great fish has long been questioned. In c. 409 C.E., Augustine of Hippo wrote to Deogratias concerning the challenge of some to the miracle recorded in the Book of Jonah. He writes:

"The last question proposed is concerning Jonah, and it is put as if it were not from Porphyry, but as being a standing subject of ridicule among the Pagans; for his words are: “In the next place, what are we to believe concerning Jonah, who is said to have been three days in a whale’s belly? The thing is utterly improbable and incredible, that a man swallowed with his clothes on should have existed in the inside of a fish. If, however, the story is figurative, be pleased to explain it. Again, what is meant by the story that a gourd sprang up above the head of Jonah after he was vomited by the fish? What was the cause of this gourd’s growth?” Questions such as these I have seen discussed by Pagans amidst loud laughter, and with great scorn." (Letter CII, Section 30)

Augustine responds that if one is to question one miracle, then one should question all miracles as well (section 31). Nevertheless, despite his apologetic, Augustine views the story of Jonah as a figure for Christ. For example, he writes: "As, therefore, Jonah passed from the ship to the belly of the whale, so Christ passed from the cross to the sepulchre, or into the abyss of death. And as Jonah suffered this for the sake of those who were endangered by the storm, so Christ suffered for the sake of those who are tossed on the waves of this world." Augustine credits his allegorical interpretation to the interpretation of Christ himself (Matt. 12:39,40), and he allows for other interpretations as long as they are in line with Christ's.

Islamic interpretation

In the Qur'an, Jonah is called Yunus (see Similarities between the Bible and the Qur'an).

Modern interpretation

In Jonah 2:1 (1:17 in English translation), the Hebrew text reads dag gadol (דג גדול), which literally means "great fish." The LXX translates this phrase into Greek as ketos megas (κητος μεγας). The term ketos alone means "huge fish," and in Greek mythology the term was closely associated with sea monsters. (See http://www.theoi.com/Ther/Ketea.html for more information regarding Greek mythology and the Ketos.) Jerome later translated this phrase as piscis granda in his Latin Vulgate. However, he translated ketos as cetus in Matthew 12:40.

At some point, cetus became synonymous with whale (e.g. cetyl alcohol, which is alcohol derived from whales). In his 1534 translation, William Tyndale translated the phrase in Jonah 2:1 as "greate fyshe," and he translated the word ketos (Greek) or cetus (Latin) in Matthew 12:40 as "whale." Tyndale's translation was, of course, later incorporated into the Authorized Version of 1611. Since, the "great fish" in Jonah 2 has been most often interpreted as a whale.

The throats of many large whales (as well as that of a large whale shark specimen, which could be found in the Mediterranean) can accommodate passage of an adult human. There are some 19th century accounts of whalers being swallowed by sperm whales and living to tell about it, but these stories remain unverified.

Historical and literary criticism

Some biblical scholars believe Jonah's prayer (2:2-9) to be a later addition to the story (see source criticism for more information on how such conclusions are drawn). Despite questions of its source, the prayer carries out an important function in the narrative as a whole.

At this point in the story, the reader would expect Jonah to repent, yet Jonah does not repent. The prayer is not a psalm of lament; rather, it is a psalm of thanksgiving. The presence of the prayer, then, serves to interpret the swallowing of the fish to be God's salvation. God has lifted Jonah out of Sheol and set him on the path to carry out His will. The story of descent (from Israel, to Tarshish, to the sea, to under the sea) becomes the story of ascent (from the belly of the fish, to land, to the city of Nineveh).

Thus, the use of a thanksgiving psalm instead of a lament psalm creates an important theological point. In the popular understanding of Jonah, the fish is interpreted to be the low point of the story. Yet even the fish is an instrument of God's sovereignty and salvation.

Bibliography

- Abegg, Martin, Jr., et al. The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible: The Oldest Known Bible Translated for the First Time into English. New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 1999.

- Cathcart, Kevin J. and Robert P. Gordon. The Targum of the Minor Prophets. The Aramaic Bible, Vol 14. Wilmington, De.: Michael Glazier, Inc., 1989.

External links

Translations

Jewish translations

- Jewish Publication Society "Tanakh" (1917)

- Yonah - Jonah (Judaica Press) translation with Rashi's commentary at Chabad.org

Christian translations

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org (ESV, KJV, Darby, American Standard Version, Bible in Basic English)

- New Revised Standard Version

- New American Version

- Revised Standard Version

- New International Version and others (Bible Gateway)

- Authorised King James Version (Wikisource)

- BlueLetter Bible (King James Version and others, plus commentaries)

Ancient texts, translations

About

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Book of Jonah (1901-1905)

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Jonah (1911)

- Jonah on the Web, annotated directory and art galleries

- Study notes on the Book of Jonah by Dr. Tim Bulkeley

- Jonah Study notes by Pastor Bob Coy

- Biblical Scholarship: Book of Jonah

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.