Arapaho

| Arapaho |

|---|

| Total population |

| 5,000 |

| Regions with significant populations |

| United States (Colorado, Oklahoma, Wyoming) |

| Languages |

| English, Arapaho |

| Religions |

| Christianity, other |

| Related ethnic groups |

| Cheyenne and other Algonquian peoples |

The Arapaho (in French: Gens de Vache) tribe of Native Americans historically living on the eastern plains of Colorado and Wyoming. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Sioux. Arapaho is an Algonquian language closely related to Gros Ventre, who are seen as an early offshoot of the Arapaho. Blackfoot and Cheyenne are the other Algonquian languages on the Plains, but are quite different from Arapaho. By the 1850s, Arapaho bands separated into two tribes: the Northern Arapaho and Southern Arapaho. The Northern Arapaho Nation has lived since 1878, with the Eastern Shoshone on the Wind River Reservation, the seventh largest reservation in the United States. The Southern Arapaho Tribe lives with the Southern Cheyenne in Oklahoma. Together their members are enrolled as a federally recognized tribe, the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes.

Name

The name Arapaho might have come from the Pawnee word for "traders." The Arapahos called themselves Hinono-eino or Inuna-ina, which can be translated "our people." Today they also use the word Arapaho (sometimes spelled Arapahoe).

They were also known as hitanwo'iv ("people of the sky" or "cloud people") by their Cheyenne allies. Others called them "dog-eaters."[1]

History

Pre-Contact

There is no direct historical or archaeological evidence to suggest how and when Arapaho bands entered the Plains culture area. Before European expansion into the area in the seventeenth century, the Arapaho Indian tribe most likely lived in Minnesota and North Dakota. They were pushed westward into South Dakota, Nebraska, Colorado, Wyoming, and Kansas.

They were originally a sedentary, agricultural people with permanent villages and used dogs to pull travois with their belongings on them. When the Europeans came to North America, the Arapaho saw the Europeans' horses and realized that they could travel quicker and further with horses instead of dogs. They raided other Indian tribes, primarily the Pawnee and Comanche, to obtain horses and became successful hunters. Later on, they became great traders and often sold furs to other tribes.

Split into Northern and Southern groups

By 1800, the Arapaho had begun coalescing into Northern and Southern groups. The Northern Arapaho settled in Wyoming, around the North Platte River. The Southern Arapaho settled in Colorado along the Arkansas River.

The Northern Arapaho assisted the Northern Cheyenne (who had also separated into two groups) and Lakota in driving the Kiowa and Comanche south from the Northern Plains. They became prosperous traders, until the expansion of American settlers onto their lands after the Civil War.[2]

Together they were a formidable military force, successful hunters, and active traders with other tribes. At the height of their alliance, their combined hunting territories spanned from Montana to Texas.[3]

The Arapaho signed the Fort Laramie Treaty with the United States in 1851. It recognized and guaranteed their rights to traditional lands in portions of Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, and Wyoming. The US could not enforce the treaty, however, and European-American trespassers overran Indian lands. There were repeated conflicts between settlers and members of the tribes.

Indian Wars

The Arapaho were involved in the Indian Wars between the colonial or federal government and various native tribes. The Northern Arapaho together with their allies the Northern Cheyenne fought alongside the Sioux in the northern plains. They participated in the Battle of the Little Bighorn, also known as "Custer's Last Stand." The Southern Arapaho with the Southern Cheyenne were involved in the conflicts as allies of the Comanche and Kiowa in the southern plains. Southern Arapaho died with Black Kettle's band of Southern Cheyenne at the Sand Creek Massacre.

- Sand Creek Massacre

During November 1864, a small encampment of Cheyenne and Arapaho became the victims of a controversial attack by the Union Army, led by Colonel John Chivington. Later congressional investigations resulted in short-lived U.S. public outcry against the slaughter of the Native Americans.[4] This attack is now known as the Sand Creek Massacre.

Though the Cheyenne were settled peacefully in land granted them by the U.S. government in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, white settlers were increasingly encroaching on their lands. Even the U.S. Indian Commissioner admitted that "We have substantially taken possession of the country and deprived the Indians of their accustomed means of support."[5]

Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle asked William Bent, the white husband of a Cheyenne woman, Owl Woman, to persuade the Americans to negotiate peace. Believing peace had been agreed upon, Black Kettle moved to a camp along Sand Creek in southeastern Colorado along with a group of several hundred Cheyenne and Arapaho.

However, on the morning of November 28, Chivington and his army of 1,200 captured William Bent's son Robert, and forced him to guide them to the campsite.[6] As instructed, Black Kettle was flying both the American flag and a white flag above his tipi, indicating that they were a peaceful camp. As the troops descended upon the camp, Black Kettle gathered his people under the flag, believing in its protection. Ignoring the flags, the American soldiers they savagely killed and mutilated the unarmed men, women, and children. Approximately 150 died.

Eugene Ridgely, a Cheyenne-Northern Arapaho artist, is generally credited with bringing to light the fact that Arapahos were involved with the Massacre. His children, Gail Ridgely, Benjamin Ridgley, and Eugene "Snowball" Ridgely, were instrumental in designating the massacre site as a National Historic Site.

- Battle of the Little Bighorn

In 1875, the last serious Sioux war erupted, when the Dakota gold rush penetrated the Black Hills. The U.S. Army did not keep miners off Sioux (Lakota) hunting grounds; yet, when ordered to take action against bands of Sioux hunting on the range, according to their treaty rights, the Army moved vigorously. In 1876, after several indecisive encounters, General George Custer found the main encampment of the Lakota and their allies at the Battle of Little Big Horn. Custer and his men — who were separated from their main body of troops — were all killed by the far more numerous Indians who had the tactical advantage. They were led in the field by Crazy Horse and inspired by Sitting Bull's earlier vision of victory.

The Northern Arapaho also participated in the Battle of the Little Bighorn, also known as "Custer's Last Stand." It occurred on June 25 and June 26, 1876, near the Little Bighorn River in eastern Montana Territory. It is estimated that population of the encampment of the Cheyenne, Lakota, and Arapaho along the Little Bighorn River was approximately 10,000, which would make it one of the largest gathering of Native Americans in North America in pre-reservation times.

The battle was the most famous action of the Great Sioux War of 1876 (also known as the Black Hills War). It was an overwhelming victory for the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho, led by several major war leaders, including Crazy Horse and Gall, inspired by the visions of Sitting Bull (Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake). The U.S. Seventh Cavalry, including the Custer Battalion, a force of 700 men led by George Armstrong Custer, suffered a severe defeat.

The Cheyenne, along with the Lakota and a small band of Arapaho, annihilated George Armstrong Custer and much of his 7th Cavalry contingent of Army soldiers. The Battle of the Little Bighorn, also known as "Custer's Last Stand," was an armed engagement between combined forces of Lakota, Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho people against the 7th Cavalry Regiment of the United States Army.

Move to Reservations

- Southern Arapaho

The US government brought the tribes to council again in 1867, to achieve peace under the Medicine Lodge Treaty. It promised the Arapaho a reservation in Kansas, but they disliked the location. The Arapaho accepted a reservation with the Cheyenne in Indian Territory, so both tribes were forced to remove south near Fort Reno in present-day Oklahoma.[3]

The Dawes Act broke up the Cheyenne-Arapaho land base. All land not allotted to individual Indians was opened to settlement in the Land Run of 1892. The Curtis Act of 1898 dismantled the tribal governments in an attempt to have the tribal members assimilate to United States conventions and culture.

After the Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act passed in 1936, the Cheyenne and Arapaho organized a single tribal government in 1937.[2] The Indian Self-Determination Act of 1975 further enhanced tribal development.

- Northern Arapaho

The Wind River Indian Reservation was established for the Eastern Shoshone in 1868. The village of Arapahoe was originally established as a sub-agency to distribute rations to the Arapaho and at one time had a large trading post.

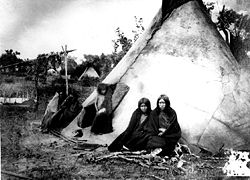

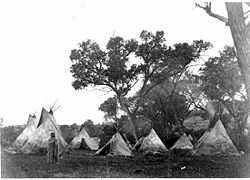

Culture

Like other Plains Indians, the Arapaho lived in tipis which the women made from buffalo hide. Nomadic people, they moved from place to place following the herds, so they had to design their tipis so that they could be transported easily. It is said that a whole village could pack up their homes and belongings and be ready to leave in only an hour. The Arapaho were great riders and trainers of horses, using them both for hunting buffalo and raiding other tribes and white settlers.

In addition to buffalo, they also hunted elk and deer as well as catching fish. They were known to eat their dogs when no other food was available.[7] The children often fished and hunted with their fathers for recreation. They also played many games.

In winter the tribe split up into small bands that set up camps sheltered in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains in present-day Colorado. In late spring they moved out onto the Plains into large camps to hunt buffalo gathering for the birthing season. In mid-summer Arapahos traveled into the Parks region of Colorado to hunt mountain herds, returning onto the Plains in late summer to autumn for ceremonies and for collective hunts of herds gathering for the rutting season. In particular, they gathered for the Sun Dance festival at the time of the summer solstice.

Religion

The Arapaho are a spiritual people, believing in a creator called Be He Teiht. They also believe in the close relationship between the land, all creatures, and themselves. Their spiritual beliefs lead them to live in harmony in what they call the "World House," and they place great emphasis on sharing since what a person gives away will come back multiplied many times over.[8]

For the Arapaho symbolism is found in everyday activities. In particular, the women painted and crafted designs on clothing and tipis that depicted spiritual beings and tribal legends.[1]

The Sun Dance is especially significant, and is an annual ceremony in which they ask for the renewal of nature and future tribal prosperity. An Offerings Lodge is constructed with poles, with a sacred tree trunk at the center around which sacred rituals are performed. It is a test of endurance for participants since they must go without food or sleep for many days. However, Arapaho do not practice the extreme self-torture common among other Plains tribes.[1]

The Arapahos were also active proponents on the Ghost Dance religion in the 1880s, especially those who were relocated to the Wind River Reservation.

Language

The Arapaho language (also Arapahoe) is a Plains Algonquian language (an areal rather than genetic grouping) spoken almost entirely by elders in Wyoming. The language, which is in great danger of becoming extinct, has diverged very significantly phonologically from its posited proto-language, Proto-Algonquian.

Contemporary Arapaho

Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes

The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes are a united, federally recognized tribe of Southern Arapaho and Southern Cheyenne people in western Oklahoma.

The tribal government consists of the Tribal Council, Executive Branch, Legislative Branch, and Judicial Branch. The Tribal Council includes all tribal members over the age of 18.[9] The Executive Branch is led by the Governor and Lieutenant Governor. The Legislative Branch is made up of legislators from the four Arapaho districts and four Cheyenne districts. The Judicial Branch includes a Supreme Court, including one Chief Justice and four Associate Justices; a Trial Court, composed of one Chief Judge and at least one Associate Judge; and any lower courts deemed necessary by the Legislature.[10] In 2006 the tribes voted and ratified the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes Constitution which replaced the 1975 constitution.[11]

The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes are headquartered in Concho, Oklahoma.

The tribe operates three tribal smoke shops and four casinos: the Lucky Star Casino in Clinton, the Lucky Star Casino in Concho, the Feather Warrior Casino in Watonga, and the Feather Warrior Casino in Canton.[12] They also issue their own tribal vehicle tags. The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribal Tribune is the tribe's newspaper.[12] The Cheyenne-Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma Culture and Heritage Program teaches hand games, powwow dancing and songs, horse care and riding, buffalo management, and Cheyenne and Arapaho language, and sponsored several running events.[13]

In partnership with Southwestern Oklahoma State University, the tribe founded the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribal College on August 25, 2006. Dr. Henrietta Mann, enrolled tribal member, currently is president. The campus is in Weatherford, Oklahoma and the school offers programs in Tribal Administration, American Indian Studies, and General Studies.[14]

Casinos

In July of 2005, Arapahos won a contentious court battle with the State of Wyoming to get into the gaming or casino industry. The 10th Circuit Court ruled that the State of Wyoming was acting in bad faith when it would not negotiate with the Arapahos for gaming. Presently, the Arapaho Tribe owns and operates high-stakes, Class III gaming at the Wind River Casino, Little Wind Casino and 789 Smoke Shop & Casino. They are regulated by a Gaming Commission composed of three Tribal members. The Northern Arapaho Tribe opened the first casinos in Wyoming.

Meanwhile, the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes operate three casinos: the Lucky Star Casino in Clinton, the Feather Warrior Casino in Watonga, and the Feather Warrior Casino in Canton.[12]

Wind River Indian Reservation

Wind River Indian Reservation is an Indian reservation shared by the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho tribes of Native Americans in the central western portion of the U.S. state of Wyoming. It is the seventh-largest Indian reservation by area in the United States, encompassing a land area of 8,995.733 km² (3,473.272 sq mi), encompassing most of Fremont County [15]. The reservation is surrounded by the Wind River Mountain Range, Owl Creek Mountains, and the Absaroka Mountains. The 2000 census reported a population of 23,250 inhabitants.[16] The largest town is Riverton. Headquarters are at Fort Washakie. Also home to the Wind River Casino, Little Wind Casino, 789 Smoke Shop & Casino (All Northern Arapahoe) and Shoshone Rose Casino (Eastern Shoshone), which are the only casinos in Wyoming.

The Wind River Indian Reservation was established for the Eastern Shoshone Indians in 1868. Camp Auger, a military post with troops was established at the present site of Lander on June 28, 1869. In 1870 the name was changed to Camp Brown and in 1871 the post was moved to the current site of Fort Washakie. The nickname was changed to honor the Shoshone Chief Washakie in 1878 and continued to serve as a military post until its abandonment in 1909.[17] A government school and hospital functioned for many years east of Fort Washakie and children were sent here to board during the school year. St. Michael's at Ethete was constructed in 1917-20. The village of Arapahoe was originally established as a sub-agency to distribute rations to the Arapaho and at one time had a large trading post. In 1906 a portion of the reservation was ceded to white settlement and Riverton evolved on some of this land. Lands were allotted in the 1800's to the various families and names were anglicized. Irrigation was brought in to develop farming and ranching and a flour mill constructed near Fort Washakie.[18]

Of the population in 2000, 6,728 (28,9%) were Native Americans (full or part) and of them 54% were Arapaho and 30% Shoshone.[16] Of the Native American population, 22% spoke a language other than English at home.

Notable Arapahos

- Chief Little Raven (ca. 1810-1889), negotiated peace between the Southern Arapaho and Cheyenne and the Comanche, Kiowa, and Plains Apache. He secured rights to the Cheyenne-Arapaho Reservation in Indian Territory.[19]

- Chief Niwot or Left Hand (c. 1825-1864) was a tribal leader of the Arapahoe people and played an important part in the history of Colorado. His people lived along the Front Range often wintering in Boulder Valley, site of the future Boulder, Colorado. Despite breaching the borders of Arapaho territory, early prospectors were welcomed by Niwot in Boulder Valley during the Colorado Gold Rush. Throughout Boulder County, many places are attributed to him or his band of Araphos. The town of Niwot, Colorado, Left Hand Canyon, Niwot Mountain, and Niwot Ridge are all named for him. Niwot died with many of his people at the hands of the Colorado Territory Militia in the Sand Creek Massacre.

- Chief Niwot (Left Hand) (ca. 1840-1911), celebrated warrior and advocate for Arapahos in Washington D.C. He brought the Ghost Dance to the tribe and served as Principal Chief.[20]

- Sherman Coolidge (Runs-on-Top) (1862–1932), Episcopal minister and educator, nominated as a "Wyoming Citizen of the Century." [21]

- Carl Sweezy (1881–1953), early professional Native American fine artist

- Mirac Creepingbear (1947–1990), Arapaho-Kiowa painter

- Harvey Pratt (b. 1941), contemporary Cheyenne-Arapaho artist

In Literature

In Centennial, James A. Michener's epic historical novel about the West from prehistoric to modern times, the fourth chapter is about the Arapaho peoples and their customs.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Carl Waldman, Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes (New York, NY: Checkmark Books, 2006, ISBN 978-0816062744).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Fowler, Loretta. Arapaho, Southern., Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture, retrieved 7 Feb 2009

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Moore, John H. Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture. (retrieved 7 Feb 2009)

- ↑ Utley and Washburn, 228.

- ↑ Legends of America, Chief Black Kettle - A Peaceful Leader Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- ↑ Dee Alexander Brown, Bury my heart at Wounded Knee; an Indian history of the American West (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1971, ISBN 0030853222).

- ↑ Kathy Weiser, Arapaho - Great Buffalo Hunters of the Plains Legends of America, 2010. Retrieved October 5, 2011.

- ↑ Margaret Coel, Arapaho Facts, Traditions & Beliefs Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ↑ Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes Constitution, Article V, Section 1

- ↑ Cheyenne-Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma Constitution and Bylaws. 1975 (retrieved 7 Feb 2009)

- ↑ http://www.c-a-tribes.org/cheyenne-arapaho-tribes-constitution

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Cheyenne & Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma. 2007 (retrieved 7 Feb 2009) Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "ca" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Culture. Cheyenne & Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma. 2007 (retrieved 7 Feb 2009)

- ↑ General Information. Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribal College. (retrieved 2 Nov 2009)

- ↑ Background of Wind River Reservation

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 2000 Census, U.S. Census Bureau

- ↑ Eastern Shoshone Tribal Culture

- ↑ Eastern Shoshone Tribal Culture

- ↑ May, Jon D. Little Raven (ca. 1810-1889). Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture. (retrieved 7 February 2009)

- ↑ May, Jon D. Left Hand (ca. 1840-1911). Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture. (retrieved 7 February 2009)

- ↑ Wyoming Citizen of the Century Nominee Sherman Coolidge. University of Wyoming American Heritage Center. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brown, Dee Alexander. Bury my Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1971. ISBN 0030853222

- Grinnell, George Bird. The Cheyenne Indians: Their History and Lifeways Vol 1. Bloomington, IN: World Wisdom, Inc., 2008. ISBN 978-1933316604

- Hinz-Penner, Raylene. Searching for Sacred Ground: The Journey of Chief Lawrence Hart, Mennonite. Telford, PA: Cascadia Publishing House, 2007. ISBN 978-1931038409

- Mann, Henrietta. Cheyenne-Arapaho Education 1871-1982. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 1997. ISBN 978-0870814624

- Moore, John L. The Cheyenne. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 1996. ISBN 978-0631218623

- Waldman, Carl. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. New York, NY: Checkmark Books, 2006. ISBN 978-0816062744

- Weiser, Kathy. Arapaho - Great Buffalo Hunters of the Plains Legends of America, 2010. Retrieved October 5, 2011.

External links

- The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes, official website

- Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma Constitution and By-Laws

- Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribal College

- Northern Arapaho Tribe

- Chief Washakie Foundation

| ||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.