Ottoman-Habsburg wars

| Ottoman-Habsburg wars | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Ottoman Wars in Europe | |||||||

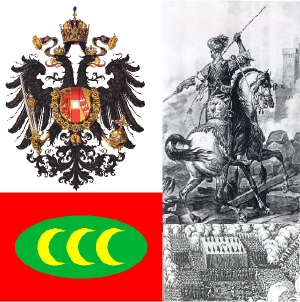

From top-left clockwise: Austrian coat of arms, Ottoman Mameluke, Imperial Troops in battle, Flag of the Ottoman Empire. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Combatants | |||||||

| Habsburg Dynasty:

Non-Habsburg Allies: Template:Country data Moldavia Moldavia[1]

Template:Country data Venice |

Flag of Ottoman Empire Ottoman Empire Template:Country data Moldavia Moldavia[3] | ||||||

| Ottoman-Habsburg wars |

|---|

| Mohacs - Campaign of Ferdinand I - Balkan campaign of Suleiman - Vienna - Little War - Koszeg - Tunis - Osijek - Preveza - Campaign of Suleiman (1543) - Eger - Malta - Szigetvar - Lepanto (1571) - Thirteen Years War - Battle of Sisak - Keresztes - Saint Gotthard - Vienna (1683) - Mohacs (1687) - Slankamen - Zenta - Peterwardein - Grocka |

| Ottoman-Hungarian Wars |

|---|

| Nicopolis – Varna – Kosovo – Belgrade – Mohács |

The Ottoman-Habsburg wars refers to the military conflicts between the Ottoman Empire and the Habsburg dynasties of the Austrian Empire, Habsburg Spain and in certain times, the Holy Roman Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary. The war would be dominated by land campaigns in Hungary. Initially, Ottoman conquests in Europe proved successful with a decisive victory at Mohacs reducing the Kingdom of Hungary to the status of an Ottoman tributary.[4]

By the 16th century, the Ottomans had become an existential threat to Europe, with Ottoman Barbary ships sweeping away Venetian possessions in the Aegean and Ionia. The Protestant Reformation, the France-Habsburg rivalry and the numerous civil conflicts of the Holy Roman Empire served as distractions. Meanwhile the Ottomans had to contend with the Persian Shah and the Mameluke Sultanate, both of whom were defeated and the latter fully annexed into the empire.

Later, the Peace of Westphalia and the Spanish War of Succession in the 17th and 18th centuries respectively left the Austrian Empire as the sole firm possession of the House of Habsburg. By then, however, European advances in guns and military tactics outweighed the skill and resources of the Ottomans and their elite Janissaries, thus ensuring Habsburg dominance on land. The Great Turkish War ended with three decisive Holy League victories at Vienna, Mohacs and Zenta. The wars came to an end when the Austrian Empire and the Ottoman Empire signed an alliance with the German Empire prior to World War I. Following their defeat in that war, both Empires were dissolved and both Houses continue to claim the title of Caesar.

Origins

Main article in Byzantine-Ottoman wars

The origins of the wars are clouded by the fact that although the Habsburgs were occasionally the Kings of Hungary and Germany (though almost always that of Germany after the 15th century), the wars between the Hungarians and the Ottomans included other Dynasties as well. Naturally, the Ottoman Wars in Europe attracted support from the West, where the advancing and powerful Islamic state was seen as a threat to Christendom in Europe. The Crusades of Nicopolis and of Varna marked the most determined attempts by Europe to halt the Turkic advance into Central Europe and the Balkans.

For a while the Ottomans were too busy trying to put down Balkan rebels such as Vlad Dracula. However, the defeat of these and other rebellious vassal states opened up Central Europe to Ottoman invasion. The Kingdom of Hungary now bordered the Ottoman Empire and its vassals.

After King Louis II of Hungary was killed at the Battle of Mohacs, his widow Queen Mary fled to her brother the Archduke of Austria, Ferdinand I. Ferdinand's claim to the throne of Hungary was further strengthened by the fact that he had married Anne, the sister of King Louis II and the only family member claimant to the throne of the shattered Kingdom. Consequently Ferdinand I was elected King of Bohemia and at the Diet of Bratislava he and his wife were elected King and Queen of Hungary. This clashed with the Turkish objective of placing the puppet John Szapolyai on the throne, thus setting the stage for a conflict between the two powers.

Austrian advance

Ferdinand I attacked Hungary, a state severely weakened by civil conflict, in 1527, in an attempt to drive out John Szapolyai and enforce his authority there. John was unable to prevent Ferdinand's campaigning which saw the capture of Buda and several other key settlements along the Danube. Despite this, the Ottoman Sultan was slow to react and only came to the aid of his vassal when he launched a huge army of about 120,000 men on 10 May 1529.[5]

Siege of Vienna

- Further information: Siege of Vienna

The Ottoman Sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent, easily wrestled from Ferdinand most of the gains he had achieved in the previous two years - to the disappointment of Ferdinand I, only the fortress of Bratislava resisted. Considering the size of Suleiman's army and the devastation wrought upon Hungary in the previous few years it is not surprising that the will to resist one of the world's powerful states was lacking in many of the recently garrisoned Habsburg settlements.

The Sultan arrived at Vienna on 27 September the same year. Ferdinand's army was some 16,000 strong - he was outnumbered roughly 7 to 1 and the walls of Vienna were an invitation to Ottoman cannon (6ft thick along some parts). Nonetheless, Ferdinand defended Vienna with great vigour. By October 12, after much mining and counter-mining an Ottoman war council was called and on October 14 the Ottomans abandoned the siege. The retreat of the Ottoman army was hampered by the brave resistance of Bratislava which once more bombarded the Ottomans. Early snowfall made matters worse and it would be another three years before Suleiman could campaign in Hungary.

Little War

After the defeat at Vienna, the Ottoman Sultan had to turn his attention to other parts of his impressive domain. Taking advantage of this absence, Archduke Ferdinand launched an offensive in 1530, recapturing Gran and other forts. An assault on Buda was only thwarted by the presence of Ottoman Turkish soldiers.

Much like the previous Austrian offensive, the return of the Ottomans forced the Habsburgs in Austria to go on the defensive once more. In 1532 Suleiman sent a massive Ottoman army to take Vienna. However, the army took a different route to Koszeg. After a heroic defence by a mere 700-strong Austrian force, the defenders accepted an "honorable" surrender of the fortress in return for their safety. After this, the Sultan withdrew content with his success and recognizing the limited Austrian gains in Hungary, whilst at the same time forcing Ferdinand to recognize John Szapolyai as King of Hungary.

Whilst the peace between the Austrians and the Ottomans would last for nine years, John Szapolyai and Ferdinand found it convenient to continue skirmishes along their respective borders. In 1537 Ferdinand broke the peace treaty by sending his ablest generals to a disastrous siege of Osijek which saw another Ottoman triumph. Even so, by the Treaty of Nagyvárad, Ferdinand was recognized as the heir of the Kingdom of Hungary.

The death of John Szapolyai in 1540 saw Ferdinand's inheritance robbed; it was instead given to John's son John II Sigismund. Attempting to enforce the treaty, the Austrians advanced on Buda where they experienced another defeat by Suleiman; the elderly Austrian General Rogendorf proved to be incompetent. Suleiman then finished off the remaining Austrian troops and proceeded to de facto annex Hungary. By the time a peace treaty was enforced in 1551, Habsburg Hungary had been reduced to little more than border land. However, at Eger the Austrians achieved a stunning victory, thanks in part to the efforts of the civilians present.

After the seizure of Buda by the Turks in 1541, the West and North Hungary recognized a Habsburg as king ("Royal Hungary"), while the central and southern counties were occupied by the Sultan ("Ottoman Hungary") and the east became the Principality of Transylvania.

The Little war saw wasted opportunities on both sides; Austrian attempts to increase their influence in Hungary were just as unsuccessful as the Ottoman drives to Vienna. Nonetheless, there were no illusions as to the status quo; the Ottoman Empire was still a very powerful and dangerous threat. Even so, the Austrians would go on the offensive again, their generals building a bloody reputation for so much loss of life. Costly battles like those fought at Buda and Osijek were to be avoided, but not absent in the upcoming conflicts. In any case Habsburg interests were split 3-way between fighting for a devastated European land under Islamic control, trying to stop the gradual decentralization of Imperial authority in Germany, and Spain's ambitions in North Africa, the Low Countries and against the French. Having said this, the Ottomans, whilst hanging on to their supreme power, could not expand upon it as much as they did in the days of Mehmet and Bayezid. Whilst the nadir of the Empire had yet to come, it's stagnation would be characterized by the same campaigning that led to little real expansion. To the east lay further wars against their Shi'ite opponents, the Safavids.

Suleiman the Magnificent led one last final campaign in 1566 against "the infidels" at the Siege of Szigetvar. The Siege was meant to be only a temporary stop before taking on Vienna. However, the fortress withstood against the Sultan's armies. Eventually the Sultan, already an old man at 72 years (ironically campaigning to restore his health), died. The Royal Physician was strangled to prevent news from reaching the troops and the unaware Ottomans took the fort, ending the campaign shortly afterward without making a move against Vienna.

War in the Mediterranean

1480 - 1540

Meanwhile, the Ottoman Empire rapidly began displacing her Christian opponents at Sea. In the 14th century, the Ottomans had only a small navy. By the 15th century, hundreds of ships were in the Ottoman arsenal taking on Constantinople and challenging the naval powers of the Italian Republics of Venice and Genoa. In 1480, the Ottomans unsuccessfully laid siege to Rhodes Island, the stronghold of the Knights of St. John. When the Ottomans returned in 1522, they were more successful and the Christian powers lost a crucial naval base.

In retaliation, Charles V led a massive Holy League of 60,000 soldiers against the Ottoman supported city of Tunis. After Hayreddin Barbarossa's fleet was defeated by a Genoan one, Charles put 30,000 of the city's residents to the sword. Afterwards, the Spanish placed a friendlier Muslim leader in power. The campaign was not an unmitigated success; many Holy League soldiers succumbed to dysentery, only natural for such a large overseas army. Furthermore, much of Barbarossa's fleet was not present in North Africa and the Ottomans won a victory against the Holy League in 1538 at the Battle of Preveza.

Siege of Malta

- Further information: Siege of Malta (1565)

Despite the loss of Rhodes, Cyprus, an island further from Europe than Rhodes, remained Venetian. When the Knights of St. John moved to Malta, the Ottomans found that their victory at Rhodes only displaced the problem; Ottoman ships came under frequent attacks by the Knights, as they attempted to stop Ottoman expansion to the West. Not to be outdone, Ottoman ships struck many parts of southern Europe and around Italy, as part of their wider war with France against the Habsburgs (See Italian Wars). The situation finally came to a head when Suleiman, the victor at Rhodes in 1522 and at Djerba decided in 1565 to destroy the Knight's base at Malta. The presence of the Ottoman fleet so close to the Papacy alarmed the Spanish, who began assembling first a small expeditionary force (that arrived in time for the siege) and then a larger fleet to relieve the Island. The ultra-modern star shaped fort of St Elmo was taken only with heavy casualties; the rest of the island was too much. Even so, Barbary piracy continued and the victory at Malta had no effect on Ottoman military strength in the Mediterranean.

Cyprus & Lepanto

The death of Suleiman the Magnificent in 1566 brought Selim II to power. Known by some as "Selim the Sot", he assembled a massive expedition to take Cyprus from the Venetians, an Island far closer to Ottoman-controlled Middle East then to Venice. The other military option that Selim opted out of was to assist the Moorish rebellion that had been instigated by the Spanish crown to root out disloyal Moors. Had Suleiman succeeded in landing in the Iberian peninsula, he may have been cut off, for after he had captured Cyprus in 1571 he suffered a decisive naval defeat at Lepanto. The Holy League, assembled by the Pope to defend the Island arrived too late to save it (despite 11 months of resistance at Famagusta) but having collected so much of Europe's available military strength, sought to inflict a blow on the Ottomans, which with better supplied ammunition and armor, they did. The chance to retake Cyprus was wasted in the typical squabbling the followed the victory, so that when the Venetians signed a peace treaty with the Ottomans in 1573 they did so according to Ottoman terms.

Rise of Russia

Of greater interest in Suleiman's reign is the emergence of Russia as a new Christian power in the north. Prior to the 1570s, Muscovy was a minor power that competed against the numerous Mongols, Turks and Tatars in the region, all of whom were predominantly Muslim. Since the Ottoman Empire had control of the southern portions of the Black Sea and the Crimean Khanate possessed the northern portions in the Crimea, they were natural allies. They also provided for the Ottomans a supply of slaves taken from Tatar raids into neighboring Christian Ukraine, most prominently that of Roxelana. Thus, when the insane Ivan the terrible successfully avenged years of defeat by sacking the city of Kazan in 1552, it was to the shock of the Ottoman Sultanate. The fall of Kazan had no immediate implications on the Empire of the Turks. Nonetheless, Russia's military power in the Crimea would only steadily increase, whilst those of the Turkish vassals - especially that of the Khanates fell. Too far and too preoccupied with events closer at home, Suleiman could do little to stop these events and his descendants would eventually find defeating the Russians an increasingly difficult task.

Thirteen Years War 1593 - 1606

After Suleiman' death in 1566, Selim II posed less of a threat to Europe. Though Cyprus was captured at long last, the Ottomans failed against the Habsburgs at sea (see above Battle of Lepanto). Selim died not too long after, leaving his son Murad III. A hedonist and a total womanizer, Murad spent more time at his Harem than at the war front. Under such deteriorating circumstances, the Empire found itself at war with the Austrians yet again. In the early stages of the war, the military situation for the Ottomans worsened as the Principalities of Wallachia, Moldova and Transylvania each had new rulers who renounced their vassalship to the Ottomans. At the Battle of Sisak, a group of Ghazis sent to raid the insubordinate lands in Croatia were thoroughly defeated by tough Imperial troops fresh from savage fighting in the Low countries. In response to this defeat, the Grand Vizier launched a large army of 13,000 Janissaries plus numerous European levies against the Christians. When the Janissaries rebelled against the Vizier's demands for a winter campaign, the Ottomans had captured little other than Veszperm.

1594 saw a more fruitful Ottoman response. An even larger army was assembled by the Grand Vizier Sinan Pasha. In the face of this threat, the Austrians abandoned a siege of Gran, a fortress that had fallen in Suleiman's career and then lost Raab. For the Austrians, their only comfort in the year came when the fortress of Komarno held out long enough against the Vizier's forces to retreat for the winter.

Despite the previous years' success, situation for the Ottomans worsened yet again in 1595. A Christian coalition of the former vassal states along with Austrian troops recaptured Gran and marched southward down the Danube. They reached Edirne; no Christian army had set foot in the region since the days of the decadent Byzantine Empire. Alarmed by the success and proximity of the threat, the new Sultan Mehmed III strangled his 19 brothers to seize power and personally marched his army to the north west of Hungary to counter his enemies' moves. In 1596, Eger, the fortress that had defied Suleiman with its "Bull's blood" fell quickly to the Ottomans. At the decisive Battle of Keresztes, a slow Austrian response was wiped out by the Ottomans. Mehmet III's inexperience in ruling showed when he failed to award the Janissaries for their efforts in battle, rather he punished them for not fighting well enough, inciting a rebellion. On top of this, Keresztes was a battle that the Austrians had almost won, save for a collapse in discipline that gave the field to the Turks. Thus, what should have sealed the war in the favor of the Ottomans dragged on.

Keresztes was a bloodbath for the Christian armies - thus it is surprising to note that the Austrians renewed the war against their enemies in the summer of 1597 with a drive southward, taking Papa, Tata, Raab and Veszperm. Further Habsburg victories were achieved when a Turkish relief force was defeated at Grosswardien. Enraged by these defeats, the Turks replied with a more energetic response so that by 1605, after much wasted Austrian relief efforts and failed sieges on both sides, only Raab remained in the hands of the Austrians. In that year a pro-Turkish vassal prince was elected leader of Transylvania by the Hungarian nobles and the war came to a conclusion with the Peace of Zsitva-Torok.