Dysentery

Dysentery is an intestinal disorder characterized by inflammation of the intestine, pain, and severe diarrhea with the frequent stools often containing blood and mucus. It is most often caused by infection due to bacteria, viruses, protozoa, or intestinal worms. Other causes include chemical irritants and certain medications, such as some steroids, that can affect bowel movements (Apel 2003). Dysentery formerly was known as flux or the bloody flux.

The most common types of dysentery are bacillary dysentry, due to infection with particular bacteria, or amebic dysentery (or amoebic dysentery), caused by an amoeba, Entamoeba histolytica. Amebic dysentery is a subcategory of an infectious disease known as amebiasis caused by this protozoan, with amebic dysentery being specific for a severe case of intestinal amebiasis (Frey 2004).

Dysentery is typically spread through unsanitary water or food containing microorganisms that damage the intestinal lining.

Amoebic dysentery

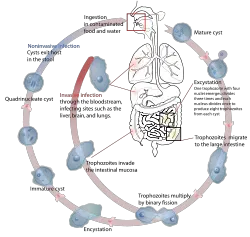

Amebic dysentery, or amebic dysentery, is caused by the amoeba Entamoeba histolytica. More generally, this amoeba causes amebiasis or amoebiasis, an infectious disease that may affect various parts of the body (intestines, liver, lungs, brain, genitals, etc.) and may have a wide range of symptoms (diarrhea, fever, cramps, etc.) or be asymptomatic. Amebiasis is one of the most common parasitic diseases, with an estimated 500 million new cases each year and with as many as 100,000 people dying each year (Frey 2004). Although amoebiasis sometimes is known as amebic dyssentery, more specifically amebic dysentery refers to a type of intestinal amebiasis in which there are symptoms such as bloody diarrhea and inflammation (Frey 2004).

Amebic dysentery may be severe, in which the organisms invades the lining of the intestine and produces sores, bloody diarrhea, vomiting, chills, fevers, and abdominal cramps.An acute case of amebic dysentery may cause such complications as inflammation of the appendix (appendicitis), a tear in the intestinal wall, or a sudden severe inflammation of the colon.

Amebic dysentery is transmitted through contaminated food and water. Entamoeba histolytica is an anaerobic parasitic protozoan. Amoebae spread by forming infective cysts, which can be found in stools and spread if whoever touches them does not sanitize their hands. There are also free amoebae, or trophozoites, that do not form cysts.

Amoebic dysentery is well known as a "traveler's dysentery" because of its prevalence in developing nations, or "Montezuma's Revenge" although it is occasionally seen in industrialized countries. About one to five percent of the general population in the United States develop amebiasis every year, but not all of these infect the intestine and many are asymptomatic; the highest infections are male homosexuals, institutionalized people, migrant workers, and recent immigrants (Frey 2004).

Bacillary dysentery

Bacillary dysentery is mostly commonly associated with three bacterial groups:

- Shigellosis is caused by one of several types of Shigella bacteria.

- Campylobacteriosis caused by any of the dozen species of Campylobacter that cause human disease

- Salmonellosis caused by Salmonella enterica (serovar Typhimurium).

Symptoms and complications

Symptoms include frequent passage of faeces/stool, loose motion and in some cases associated vomiting. Variations depending on parasites can be frequent urge with high or low volume of stool, with or without some associated mucus and even blood.

Once recovery starts, early refeeding is advocated avoiding foods containing lactose due to temporary [can persist for years] lactose intolerance.[1][2]

Treatment

The first and main task in managing any episode of dysentery is to maintain fluid intake using oral rehydration therapy. If this can not be adequately maintained, either through nausea and vomiting or the profuseness of the diarrhea, then hospital admission may be required for intravenous fluid replacement. Ideally no antimicrobial therapy is started until microbiological microscopy and culture studies have established the specific infection involved. Where laboratory services are lacking, it may be required to initiate a combination of drugs including an amoebicidal drug to kill the parasite and an antibiotic to treat any associated bacterial infection. There are several Shigella vaccine candidates in various stages of development that could reduce the incience of dysentery in endemic countries, as well as in travelers suffering from traveler's diarrhea.[3]

Amoebic dysentery can be treated with metronidazole. Mild cases of bacillary dysentery are often self-limiting and do not require antibiotics,[4] which are reserved for more severe or persisting cases; campylobacter, shigella and salmonella respond to ciprofloxacin or macrolide antibiotics.[4]

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Frey

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ DuPont HL (1978). Interventions in diarrhoeas of infants and young children. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 173 (5 Pt 2): 649–53.

- ↑ DeWitt TG (1989). Acute diarrhoea in children. Pediatr Rev 11 (1): 6–13.

- ↑ Girard MP, Steele D, Chaignat CL, Kieny MP. A Review of Vaccine Research and Development: Human Enteric Infections. Vaccine. 2006; 24(15):2732-2750.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 (March 2007) "Antibacterial drugs - Summary of antibacterial therapy", British National Formulary, Ed.53, p.276.

- ↑ Apel, Melanie Ann (author) (2003). Amebic Dysentery (Epidemics), 1st ed., Rosen Publishing Group, pp. 13. ISBN 0823941965.