Difference between revisions of "Divination" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (20 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Copyedited}}{{submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{approved}}{{Paid}} |

| + | [[Image:Rhumsiki crab sorceror.jpg|thumb|200px|right|This man in [[Rhumsiki]], [[Cameroon]], tells the future by interpreting the changes in position of various objects as caused by a fresh-water crab through ''nggàm''.]] | ||

| + | '''Divination''' is the attempt of ascertaining information by interpretation of [[omen]]s or an alleged [[supernatural]] agency. | ||

| − | [[ | + | Divination is distinguished from [[fortune-telling]] in that divination has a formal or ritualistic and often social character, usually in a [[religion|religious]] context, while fortune-telling is a more everyday practice for personal purposes. Divination is often dismissed by [[skeptic]]s, including the [[scientific community]], as being mere [[superstition]]. Nevertheless, the practice is widespread and has been known in virtually every historical period. The biblical [[prophet]]s used various forms of divination in reading the future, as did pagan priests and [[shaman]]s. In the [[New Testament]], the magi read the signs in the heavens to find the [[Christ]] child. Medieval kings and modern presidents have consulted [[astrologer]]s to determine the most propitious time for various events. Today, millions of people practice various forms of divination, sometimes without being aware of it, ranging from consulting one's daily [[horoscope]] in the newspaper to flipping a coin to decide a course of action. |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | ==History== | ||

| + | From the earliest stages of [[civilization]], people have used various means of divination to communicate with the [[supernatural]] when seeking help in their public and private lives. Divination is most often practiced as a means of foretelling the future, and sometimes the past. It is one of the primary practices used by [[shaman]]s, [[seers]], [[priests]], [[medicine men]], [[sorcerers]], and [[witches]]. Such persons are often called [[diviners]], who often belonged to special classes of priests and [[priestesses]] in both past and present civilizations, and are specially trained in the practice and interpretation of their divinatory skills. | ||

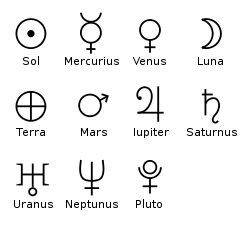

| − | + | [[Image:Astrological Glyphs.svg|thumb|250px|Astrology was one of the first sophisticated forms of divination, dating back to ancient [[Mesopotamia]]n times.]] | |

| − | + | The [[Egyptians]], [[Druids]], and [[Hebrews]] relied on scrying. The Druids also read death throes and entrails of sacrificed [[animal]]s. Augury was first systematized by the Chaldeans. The Greeks were addicted to it; and among the Romans no important action of state was undertaken without the advice of the diviners. In fact, the belief in divination has existed throughout history, among the uncivilized as well as the most civilized nations, to the present day, as the wish to know the future continually giving rise to some art of peering into it. | |

| − | + | The [[Greeks]] had their oracle which spoke for the gods. As far back as 1000 B.C.E., the [[Chinese]] had ''I Ching'', an oracle which involved the tossing and reading of long or short yarrow sticks. Another ancient Chinese divinatory practice which is still used is ''feng-shui'', or [[geomancy]], which involves the erecting of buildings, tombs, and other physical structures by determining the currents of invisible [[energy]] coursing through the earth. Presently, people also are using this principle for the arrangement of furniture in their homes. | |

| − | + | ||

| + | The types of divination, however, depended on the conditions of external nature, [[race]] peculiarities, and historical influences. The future was foretold by the aspect of the [[heavens]] ([[astrology]]); by [[dreams]], [[lots]] and [[oracles]]; or [[spirits]] were also invoked to tell the future (necromancy). In early Hebraic culture, ''teraphim'' and [[Urim and Thummim]] were queried. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In biblical times, the observation of the flight of birds for the purpose of divination is shown in ''Ecclesiastes'' 10:20: "...for a bird of the air shall carry the voice, and that which hath wings shall tell the matter." Among the [[Arabs]] the raven was a bird of [[omen]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Josephus]] narrates that a bird (an owl) alighted on the tree against which [[Agrippa]] was leaning while a prisoner at [[Rome]]; whereupon a fellow prisoner, a [[German]], prophesied that he would become king, but that if the bird appeared a second time, it would mean he would die. The Romans also understood the language of the birds, since [[Judah]] was said not to dare, even in a whisper, to advise the Emperor [[Antoninus]] to proceed against the nobles of Rome, for the birds would carry his voice onward. | ||

| + | The [[Babylonians]] divined by flies. The belief in animal omens was also widely spread among the Babylonians, who also divined by the behavior of [[fish]], as was well known. The language of [[tree]]s, which the ancient peoples, especially the Babylonians, are said to have understood, was probably known to the Babylonian Jews as early as the eighth century. [[Abraham]] learned from the sighing of the tamarisk-tree that his end was nigh. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The biblical [[Joseph]] practiced [[hydromancy]]. He divined the future by pouring water into a cup, throwing little pieces of [[gold]] or [[jewels]] into the [[fluid]], observing the figures that were formed, and predicting accordingly (''Genesis'' 54.5). [[Laban]] found out through divination that God had blessed him on account of Jacob (''Genesis'' 30:27). | ||

| + | |||

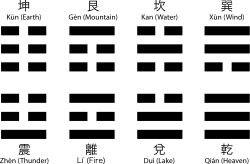

| + | [[Image:Trigrams2.svg|thumb|right|250px|The eight trigrams of the ''I Ching''.]] | ||

| − | + | Accidental occurrences were of great importance in divination, and may be taken as omens. [[Eliezer]], Abraham's servant, said: "I stand at the well ... and the damsel to whom I shall say, Let down thy pitcher, I pray thee, that I may drink; and she shall say, Drink, and I will give thy camels drink also, let the same be the wife appointed by God for Isaac" (''Genesis'' 24:12-19). The diviners advised the [[Philistines]] to send back the [[Ark]] of the Lord in order that the deaths among them might cease (''I Samuel'' 6:7-12). | |

| − | The [[ | + | Nevertheless, the Mosaic law strictly and repeatedly forbade all augury (Lev. 19:26; Deut. 28:10, etc.). The [[interpretation]] of signs, however, was not considered unlawful—nor was |

| + | the use of the [[Urim and Thummin]]: "Put the Urim and the Thummim in the breastpiece... Thus Aaron will always bear the means of making decisions for the Israelites." (Exodus 28:30) In ''I Samuel'' 14:41, King [[Saul]] reportedly said: "If this iniquity be in me or in Jonathan my son, Lord, God of Israel, give Urim; but if it be in thy people Israel, give Thummim." | ||

| − | + | In the first century B.C.E., the Roman orator [[Cicero]]'s wrote a formal treatise on the subject of divination under the title ''De divinatione'', in which he distinguishes between inductive and deductive types of divination. At the time of Jesus, the magi learned by observing the stars that the Christ child would be born at a certain time and place in [[Bethlehem]]. | |

| − | + | In the [[Middle Ages]], the [[philosophers]] were averse to divination. However, among the common folk and some mystics, the practice was well known. A common practice in the Middle Ages was to toss grain, sand, or peas onto a field in order to read the [[patterns]] after the substances fell. Divination practices in [[France]] and [[Germany]] were varied. Slivers of wood, from which the bark had been removed on one side, were thrown into the air and, according to how they fell on the peeled or on the barked side, the omen was interpreted as favorable or unfavorable. Flames leaping up on the hearth indicated that a guest was coming. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Many divinatory methods are still used today, especially in [[paganism]], [[witchcraft]], [[voodoo]], and [[Santeria]]. Some forms of [[prayer]] might also be considered a divinatory act. Many practitioners today do not feel [[signs]] of divination are absolute or fixed, but believe they still have free choices in their future. They believe divination helps them in making better choices. | |

| − | + | ==Christian response to divination== | |

| + | Today's [[Christian theology]] with includes invoking the name of the [[Holy Spirit]] and praying in the name of the saints to accomplish some personal goal, belies the fact that, for much of its history, Christianity opposed the practice of divination. In fact, wherever Christianity went, divination lost most of its old-time power, and one form, the natural, ceased almost completely. The new [[religion]] forbade all kinds of divination, and after some centuries it disappeared as an official system though it continued to have many adherents. The [[Church Fathers]] were its vigorous opponents. The tenets of [[Gnosticism]] gave it some strength, and [[Neo-Platonism]] won it many followers. | ||

| − | + | Within the Church, divination proved so strong and attractive to her new [[converts]] that [[synods]] forbade it and councils legislated against it. The [[Council of Ancyra]] in 314 decreed five years penance to consulters of diviners, and that of [[Laodicea]], about 360, forbade [[clerics]] to become [[magicians]] or to make [[amulets]], and those who wore them were to be driven out of the Church. Canon 36 of [[Orléans]] excommunicated those who practiced divination auguries, or lots falsely called ''Sortes Sanctorum'' (Bibliorum), i.e. deciding one's future conduct by the first passage found on opening a [[Bible]]. This method was evidently a great favorite, since a synod in Vannes, in 461, forbid it to clerics under pain of [[excommunication]], and that of Agde, in 506, condemned it as against piety and faith. [[Sixtus IV]], [[Sixtus V]], and the [[Fifth Council of Lateran]] likewise condemned divination. | |

| − | The | + | [[Image:Michelangelo Caravaggio 031.jpg|thumb|300px|''[[The Fortune Teller]]'', by [[Caravaggio]] (1594–95; Canvas; Louvre), depicting a palm reading.]] |

| − | + | [[Governments]] have at times acted with great severity; [[Constantius]] decreed the penalty of death for diviners. The authorities may have feared that some would-be prophets might endeavor to fulfill forcibly their predictions about the death of [[sovereigns]]. When the [[tribes]] from the North swept down over the old [[Roman Empire]] and entered the Church, it was only to be expected that some of their lesser [[superstitions]] should survive. | |

| − | The | + | All during the so-called [[Dark Ages]], divining arts managed to live in secret, but after the [[Crusades]] they were followed more openly. At the time of the [[Renaissance]] and again preceding the [[French Revolution]], there was a marked growth of methods considered noxious to the church. The latter part of the nineteenth century witnessed a revival, especially in the [[United States]] and [[England]], with such practices as [[astrology]], spiritism and other types of divination becoming widely popular. Today, divination has become commonplace, from astrology columns in newspapers, to large sections of bookstores featuring divination tools from [[palm-reading]] and [[phrenology]] to runestones, the ''I Ching'' and a vast array of [[tarot]] decks. |

| − | == Categories of divination == | + | ==Categories of divination== |

Psychologist [[Julian Jaynes]] categorized divination according to the following types: | Psychologist [[Julian Jaynes]] categorized divination according to the following types: | ||

''[[Omens and omen texts]]'': "The most primitive, clumsy, but enduring method...is the simple recording of sequences of unusual or important events." Chinese history offers scrupulously documented occurrences of strange births, the tracking of natural phenomena, and other data. Chinese governmental planning relied on this method of forecasting for long-range strategy. It is not unreasonable to assume that modern scientific inquiry began with this kind of divination; [[Joseph Needham]]'s work considered this very idea. | ''[[Omens and omen texts]]'': "The most primitive, clumsy, but enduring method...is the simple recording of sequences of unusual or important events." Chinese history offers scrupulously documented occurrences of strange births, the tracking of natural phenomena, and other data. Chinese governmental planning relied on this method of forecasting for long-range strategy. It is not unreasonable to assume that modern scientific inquiry began with this kind of divination; [[Joseph Needham]]'s work considered this very idea. | ||

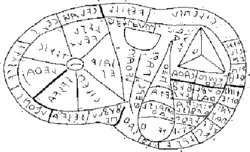

| − | ''[[Sortilege]]'' ([[cleromancy]]): This consists of the casting of lots whether with sticks, stones, bones, beans, or some other item. Modern playing cards and board games developed from this type of divination. | + | [[Image:Haruspex.png|thumb|right|250px|The sheep's liver found at Picenum with Etruscan inscriptions|Diagram of a [[sheep]]'s [[liver]], with [[Etruscan language|Etruscan]] inscriptions]] |

| + | |||

| + | ''[[Sortilege]]'' ([[cleromancy]]): This consists of the casting of lots whether with sticks, stones, bones, coins, beans, or some other item. Modern playing cards and board games developed from this type of divination. | ||

| − | ''[[Augury]]'': Divination that ranks a set of given possibilities. It can be qualitative (such as shapes, proximities, etc.): for example, [[dowsing]] | + | ''[[Augury]]'': Divination that ranks a set of given possibilities. It can be qualitative (such as shapes, proximities, etc.): for example, [[dowsing]] developed from this type of divination. The [[Roman Republic|Romans]] in classical times used [[Etruscan civilization|Etruscan]] methods of augury such as [[hepatoscopy]]. [[haruspex|Haruspices]] examined the livers of sacrificed animals. Palm-reading and the reading of tea-leaves are also examples of this type of divination. |

''[[Spontaneous]]'': An unconstrained form of divination, free from any particular medium, and actually a generalization of all types of divination. The answer comes from whatever object the diviner happens to see or hear. Some [[Christian]]s and members of other religions use a form of [[bibliomancy]]: they ask a question, riffle the pages of their [[holy]] book, and take as their answer the first passage their eyes light upon. The [[Bible]] itself expresses mixed opinions on divination; see e.g. [[Cleromancy]]. | ''[[Spontaneous]]'': An unconstrained form of divination, free from any particular medium, and actually a generalization of all types of divination. The answer comes from whatever object the diviner happens to see or hear. Some [[Christian]]s and members of other religions use a form of [[bibliomancy]]: they ask a question, riffle the pages of their [[holy]] book, and take as their answer the first passage their eyes light upon. The [[Bible]] itself expresses mixed opinions on divination; see e.g. [[Cleromancy]]. | ||

| Line 47: | Line 65: | ||

The [[methodology]] for practicing the divinatory skills seems to divide into two categories: the first is the [[observation]] and [[interpretation]] of [[natural phenomena]], and the second is the observation and interpretation of man-made "voluntary" phenomena. Natural phenomena includes two major subcategories of activity: [[astrology]] and [[hepatoscopy]]. To a lesser degree, the observation of the following occurrences also can be listed under natural phenomena: unexpected [[storms]], particular [[cloud]] formations, birth monstrosities in both [[man]] and [[animal]], howling or unnatural actions in dogs, and nightmarish dreams. | The [[methodology]] for practicing the divinatory skills seems to divide into two categories: the first is the [[observation]] and [[interpretation]] of [[natural phenomena]], and the second is the observation and interpretation of man-made "voluntary" phenomena. Natural phenomena includes two major subcategories of activity: [[astrology]] and [[hepatoscopy]]. To a lesser degree, the observation of the following occurrences also can be listed under natural phenomena: unexpected [[storms]], particular [[cloud]] formations, birth monstrosities in both [[man]] and [[animal]], howling or unnatural actions in dogs, and nightmarish dreams. | ||

| − | Man-made or "voluntary" phenomena is defined as being deliberately produced for the sole purpose of [[soothsaying]], and includes such acts as [[necromancy]], pouring oil into a basin of water to observe the formation of bubbles and rings in the receptacle, shooting [[arrows]], [[casting lots]], and numerous other acts. | + | Man-made or "voluntary" phenomena is defined as being deliberately produced for the sole purpose of [[soothsaying]], and includes such acts as [[necromancy]], pouring oil into a basin of water to observe the formation of bubbles and rings in the receptacle, shooting [[arrows]], [[casting lots]], reading tea leaves or coffee grounds and numerous other acts. |

| − | The following is a selection of the more common methods of divination: [[astrology]]: by celestial bodies | + | The following is a selection of the more common methods of divination: |

| + | *[[astrology]]: by celestial bodies | ||

| + | *[[augury]]: by the flight of birds, etc. | ||

| + | *[[bibliomancy]]: by books (frequently, but not always, religious texts) | ||

| + | *[[cartomancy]]: by cards | ||

| + | *[[cheiromancy]]/[[palmistry]]: by palms | ||

| + | *[[gastromancy]]: by [[crystal ball]] | ||

| + | *[[extispicy]]: by the entrails of animals | ||

| + | *[[I Ching divination]]: by the [[I Ching]], a form of bibliomancy combined with casting sticks or coins | ||

| + | *[[numerology]]: by numbers | ||

| + | *[[oneiromancy]]: by [[dreams]] | ||

| + | *[[onomancy]]: by names | ||

| + | *[[Ouija]]: by the use of a board supposedly combined with [[necromancy]] | ||

| + | *[[rhabdomancy]]: divination by rods | ||

| + | *[[runecasting]]/[[Runic divination]]: by [[runes]] | ||

| + | *[[scrying]]: by reflective objects | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | *Cunningham, Scott. ''Divination for Beginners: Readings the Past, Present, & Future'' | + | * Blacker, Carmen, and Michael Loewe (eds.). ''Oracles and divination''. Shambhala/Random House, 1981. ISBN 0877732140 |

| − | *Fiery, Ann. ''The Book of Divination'' | + | * Cunningham, Scott. ''Divination for Beginners: Readings the Past, Present, & Future''. Llewellyn Publications, 2003. ISBN 978-0738703848 |

| − | + | * Fiery, Ann. ''The Book of Divination''. Amazon Remainders Account, 1999. {{ASIN|B000C4SH36}} | |

| − | *Morwyn. ''The Complete Book of Psychic Arts: Divination Practices from Around the World'' | + | * Morwyn. ''The Complete Book of Psychic Arts: Divination Practices from Around the World''. Llewellyn Publications, 1999. ISBN 978-1567182361 |

| − | *O'Brien, Paul. ''Divination: Sacred Tools for Reading the Mind of God'' | + | * O'Brien, Paul. ''Divination: Sacred Tools for Reading the Mind of God''. Visionary Networks Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0979542503 |

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved January 29, 2024. | |

| − | *[http://TarotCanada.tripod.com/AppleDivination.html Apple Divination] | + | |

| − | + | *[http://TarotCanada.tripod.com/AppleDivination.html Apple Divination] ''TarotCanada.tripod.com'' | |

| − | + | *[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/05048b.htm Catholic Encyclopedia: Divination] ''www.newadvent.org'' | |

| − | *[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/05048b.htm | + | * [http://www.iranian.com/Sep96/Iranica/IranicaDivine/IranicaDivine.html Encyclopedia Iranica: Divination] ''www.iranian.com'' |

| − | + | *[http://tim.maroney.org/Essays/Theory_of_Divination.html Theory of Divination] by Tim Maroney, exploring different possibilities. ''tim.maroney.org'' | |

| − | * [http://www.iranian.com/Sep96/Iranica/IranicaDivine/IranicaDivine.html Encyclopedia Iranica: Divination] | ||

| − | *[http://tim.maroney.org/Essays/Theory_of_Divination.html Theory of Divination] by Tim Maroney, exploring different possibilities | ||

[[Category:philosophy and religion]] | [[Category:philosophy and religion]] | ||

| + | [[Category:religion]] | ||

{{Credit|156977868}} | {{Credit|156977868}} | ||

Latest revision as of 15:31, 29 January 2024

Divination is the attempt of ascertaining information by interpretation of omens or an alleged supernatural agency.

Divination is distinguished from fortune-telling in that divination has a formal or ritualistic and often social character, usually in a religious context, while fortune-telling is a more everyday practice for personal purposes. Divination is often dismissed by skeptics, including the scientific community, as being mere superstition. Nevertheless, the practice is widespread and has been known in virtually every historical period. The biblical prophets used various forms of divination in reading the future, as did pagan priests and shamans. In the New Testament, the magi read the signs in the heavens to find the Christ child. Medieval kings and modern presidents have consulted astrologers to determine the most propitious time for various events. Today, millions of people practice various forms of divination, sometimes without being aware of it, ranging from consulting one's daily horoscope in the newspaper to flipping a coin to decide a course of action.

History

From the earliest stages of civilization, people have used various means of divination to communicate with the supernatural when seeking help in their public and private lives. Divination is most often practiced as a means of foretelling the future, and sometimes the past. It is one of the primary practices used by shamans, seers, priests, medicine men, sorcerers, and witches. Such persons are often called diviners, who often belonged to special classes of priests and priestesses in both past and present civilizations, and are specially trained in the practice and interpretation of their divinatory skills.

The Egyptians, Druids, and Hebrews relied on scrying. The Druids also read death throes and entrails of sacrificed animals. Augury was first systematized by the Chaldeans. The Greeks were addicted to it; and among the Romans no important action of state was undertaken without the advice of the diviners. In fact, the belief in divination has existed throughout history, among the uncivilized as well as the most civilized nations, to the present day, as the wish to know the future continually giving rise to some art of peering into it.

The Greeks had their oracle which spoke for the gods. As far back as 1000 B.C.E., the Chinese had I Ching, an oracle which involved the tossing and reading of long or short yarrow sticks. Another ancient Chinese divinatory practice which is still used is feng-shui, or geomancy, which involves the erecting of buildings, tombs, and other physical structures by determining the currents of invisible energy coursing through the earth. Presently, people also are using this principle for the arrangement of furniture in their homes.

The types of divination, however, depended on the conditions of external nature, race peculiarities, and historical influences. The future was foretold by the aspect of the heavens (astrology); by dreams, lots and oracles; or spirits were also invoked to tell the future (necromancy). In early Hebraic culture, teraphim and Urim and Thummim were queried.

In biblical times, the observation of the flight of birds for the purpose of divination is shown in Ecclesiastes 10:20: "...for a bird of the air shall carry the voice, and that which hath wings shall tell the matter." Among the Arabs the raven was a bird of omen.

Josephus narrates that a bird (an owl) alighted on the tree against which Agrippa was leaning while a prisoner at Rome; whereupon a fellow prisoner, a German, prophesied that he would become king, but that if the bird appeared a second time, it would mean he would die. The Romans also understood the language of the birds, since Judah was said not to dare, even in a whisper, to advise the Emperor Antoninus to proceed against the nobles of Rome, for the birds would carry his voice onward. The Babylonians divined by flies. The belief in animal omens was also widely spread among the Babylonians, who also divined by the behavior of fish, as was well known. The language of trees, which the ancient peoples, especially the Babylonians, are said to have understood, was probably known to the Babylonian Jews as early as the eighth century. Abraham learned from the sighing of the tamarisk-tree that his end was nigh.

The biblical Joseph practiced hydromancy. He divined the future by pouring water into a cup, throwing little pieces of gold or jewels into the fluid, observing the figures that were formed, and predicting accordingly (Genesis 54.5). Laban found out through divination that God had blessed him on account of Jacob (Genesis 30:27).

Accidental occurrences were of great importance in divination, and may be taken as omens. Eliezer, Abraham's servant, said: "I stand at the well ... and the damsel to whom I shall say, Let down thy pitcher, I pray thee, that I may drink; and she shall say, Drink, and I will give thy camels drink also, let the same be the wife appointed by God for Isaac" (Genesis 24:12-19). The diviners advised the Philistines to send back the Ark of the Lord in order that the deaths among them might cease (I Samuel 6:7-12).

Nevertheless, the Mosaic law strictly and repeatedly forbade all augury (Lev. 19:26; Deut. 28:10, etc.). The interpretation of signs, however, was not considered unlawful—nor was the use of the Urim and Thummin: "Put the Urim and the Thummim in the breastpiece... Thus Aaron will always bear the means of making decisions for the Israelites." (Exodus 28:30) In I Samuel 14:41, King Saul reportedly said: "If this iniquity be in me or in Jonathan my son, Lord, God of Israel, give Urim; but if it be in thy people Israel, give Thummim."

In the first century B.C.E., the Roman orator Cicero's wrote a formal treatise on the subject of divination under the title De divinatione, in which he distinguishes between inductive and deductive types of divination. At the time of Jesus, the magi learned by observing the stars that the Christ child would be born at a certain time and place in Bethlehem.

In the Middle Ages, the philosophers were averse to divination. However, among the common folk and some mystics, the practice was well known. A common practice in the Middle Ages was to toss grain, sand, or peas onto a field in order to read the patterns after the substances fell. Divination practices in France and Germany were varied. Slivers of wood, from which the bark had been removed on one side, were thrown into the air and, according to how they fell on the peeled or on the barked side, the omen was interpreted as favorable or unfavorable. Flames leaping up on the hearth indicated that a guest was coming.

Many divinatory methods are still used today, especially in paganism, witchcraft, voodoo, and Santeria. Some forms of prayer might also be considered a divinatory act. Many practitioners today do not feel signs of divination are absolute or fixed, but believe they still have free choices in their future. They believe divination helps them in making better choices.

Christian response to divination

Today's Christian theology with includes invoking the name of the Holy Spirit and praying in the name of the saints to accomplish some personal goal, belies the fact that, for much of its history, Christianity opposed the practice of divination. In fact, wherever Christianity went, divination lost most of its old-time power, and one form, the natural, ceased almost completely. The new religion forbade all kinds of divination, and after some centuries it disappeared as an official system though it continued to have many adherents. The Church Fathers were its vigorous opponents. The tenets of Gnosticism gave it some strength, and Neo-Platonism won it many followers.

Within the Church, divination proved so strong and attractive to her new converts that synods forbade it and councils legislated against it. The Council of Ancyra in 314 decreed five years penance to consulters of diviners, and that of Laodicea, about 360, forbade clerics to become magicians or to make amulets, and those who wore them were to be driven out of the Church. Canon 36 of Orléans excommunicated those who practiced divination auguries, or lots falsely called Sortes Sanctorum (Bibliorum), i.e. deciding one's future conduct by the first passage found on opening a Bible. This method was evidently a great favorite, since a synod in Vannes, in 461, forbid it to clerics under pain of excommunication, and that of Agde, in 506, condemned it as against piety and faith. Sixtus IV, Sixtus V, and the Fifth Council of Lateran likewise condemned divination.

Governments have at times acted with great severity; Constantius decreed the penalty of death for diviners. The authorities may have feared that some would-be prophets might endeavor to fulfill forcibly their predictions about the death of sovereigns. When the tribes from the North swept down over the old Roman Empire and entered the Church, it was only to be expected that some of their lesser superstitions should survive.

All during the so-called Dark Ages, divining arts managed to live in secret, but after the Crusades they were followed more openly. At the time of the Renaissance and again preceding the French Revolution, there was a marked growth of methods considered noxious to the church. The latter part of the nineteenth century witnessed a revival, especially in the United States and England, with such practices as astrology, spiritism and other types of divination becoming widely popular. Today, divination has become commonplace, from astrology columns in newspapers, to large sections of bookstores featuring divination tools from palm-reading and phrenology to runestones, the I Ching and a vast array of tarot decks.

Categories of divination

Psychologist Julian Jaynes categorized divination according to the following types:

Omens and omen texts: "The most primitive, clumsy, but enduring method...is the simple recording of sequences of unusual or important events." Chinese history offers scrupulously documented occurrences of strange births, the tracking of natural phenomena, and other data. Chinese governmental planning relied on this method of forecasting for long-range strategy. It is not unreasonable to assume that modern scientific inquiry began with this kind of divination; Joseph Needham's work considered this very idea.

Sortilege (cleromancy): This consists of the casting of lots whether with sticks, stones, bones, coins, beans, or some other item. Modern playing cards and board games developed from this type of divination.

Augury: Divination that ranks a set of given possibilities. It can be qualitative (such as shapes, proximities, etc.): for example, dowsing developed from this type of divination. The Romans in classical times used Etruscan methods of augury such as hepatoscopy. Haruspices examined the livers of sacrificed animals. Palm-reading and the reading of tea-leaves are also examples of this type of divination.

Spontaneous: An unconstrained form of divination, free from any particular medium, and actually a generalization of all types of divination. The answer comes from whatever object the diviner happens to see or hear. Some Christians and members of other religions use a form of bibliomancy: they ask a question, riffle the pages of their holy book, and take as their answer the first passage their eyes light upon. The Bible itself expresses mixed opinions on divination; see e.g. Cleromancy.

Other forms of spontaneous divination include reading auras and New Age methods of Feng Shui, such as "intuitive" and Fuzion.

Common methods of divination

The methodology for practicing the divinatory skills seems to divide into two categories: the first is the observation and interpretation of natural phenomena, and the second is the observation and interpretation of man-made "voluntary" phenomena. Natural phenomena includes two major subcategories of activity: astrology and hepatoscopy. To a lesser degree, the observation of the following occurrences also can be listed under natural phenomena: unexpected storms, particular cloud formations, birth monstrosities in both man and animal, howling or unnatural actions in dogs, and nightmarish dreams.

Man-made or "voluntary" phenomena is defined as being deliberately produced for the sole purpose of soothsaying, and includes such acts as necromancy, pouring oil into a basin of water to observe the formation of bubbles and rings in the receptacle, shooting arrows, casting lots, reading tea leaves or coffee grounds and numerous other acts.

The following is a selection of the more common methods of divination:

- astrology: by celestial bodies

- augury: by the flight of birds, etc.

- bibliomancy: by books (frequently, but not always, religious texts)

- cartomancy: by cards

- cheiromancy/palmistry: by palms

- gastromancy: by crystal ball

- extispicy: by the entrails of animals

- I Ching divination: by the I Ching, a form of bibliomancy combined with casting sticks or coins

- numerology: by numbers

- oneiromancy: by dreams

- onomancy: by names

- Ouija: by the use of a board supposedly combined with necromancy

- rhabdomancy: divination by rods

- runecasting/Runic divination: by runes

- scrying: by reflective objects

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Blacker, Carmen, and Michael Loewe (eds.). Oracles and divination. Shambhala/Random House, 1981. ISBN 0877732140

- Cunningham, Scott. Divination for Beginners: Readings the Past, Present, & Future. Llewellyn Publications, 2003. ISBN 978-0738703848

- Fiery, Ann. The Book of Divination. Amazon Remainders Account, 1999. ASIN B000C4SH36

- Morwyn. The Complete Book of Psychic Arts: Divination Practices from Around the World. Llewellyn Publications, 1999. ISBN 978-1567182361

- O'Brien, Paul. Divination: Sacred Tools for Reading the Mind of God. Visionary Networks Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0979542503

External links

All links retrieved January 29, 2024.

- Apple Divination TarotCanada.tripod.com

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Divination www.newadvent.org

- Encyclopedia Iranica: Divination www.iranian.com

- Theory of Divination by Tim Maroney, exploring different possibilities. tim.maroney.org

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.