Difference between revisions of "Autism spectrum" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 112: | Line 112: | ||

=== Self-injury === | === Self-injury === | ||

| − | [[Self-injurious behavior]]s (SIB) are relatively common in autistic people, and can include head-banging, self-cutting, self-biting, and hair-pulling | + | [[Self-injurious behavior]]s (SIB) are relatively common in autistic people, and can include head-banging, self-cutting, self-biting, and hair-pulling; some of these can result in serious injury or death. |

| − | * Frequency and/or continuation of self-injurious behavior can be influenced by environmental factors ( | + | * Frequency and/or continuation of self-injurious behavior can be influenced by environmental factors (such as reward for halting self-injurious behavior). However this does not apply to younger children with autism. |

| − | * Higher rates of self-injury are | + | * Higher rates of self-injury are noted in socially isolated autistic people. This includes a [[suicide]] rate for verbal autistics that is nine times that of the general population.<ref>Amelia Hill, [https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/jul/31/autism-could-be-seen-as-part-of-personality-for-some-diagnosed-experts-say Autism could be seen as part of personality for some diagnosed, experts say] ''The Guardian'' (July 31, 2023). Retrieved January 13, 2024.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

=== Other features === | === Other features === | ||

Revision as of 17:39, 13 January 2024

| Autism spectrum disorder | |

| |

| Other names |

|

|---|---|

| Repetitively stacking or lining up objects is a common trait associated with autism. | |

| Symptoms | Difficulties in social interaction, verbal and nonverbal communication, and the presence of repetitive behavior or restricted interests |

| Complications | Social isolation, educational and employment problems, anxiety, stress, bullying, depression, self-harm |

| Usual onset | Early childhood |

| Duration | Lifelong |

| Causes | Multifactorial, with many uncertain factors |

| Risk factors | Family history, certain genetic conditions, having older parents, certain prescribed drugs, perinatal and neonatal health issues |

| Diagnostic method | Based on combination of clinical observation of behavior and development and comprehensive diagnostic testing completed by a team of qualified professionals (including psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, neuropsychologists, pediatricians, and speech-language pathologists). For adults, the use of a patient's written and oral history of autistic traits becomes more important |

| Differential diagnosis | Intellectual disability, anxiety, bipolar disorder, depression, Rett syndrome, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, schizoid personality disorder, selective mutism, schizophrenia, obsessive–compulsive disorder, social anxiety disorder, Einstein syndrome, PTSD, learning disorders (mainly speech disorders) |

| Management | Applied behavior analysis, cognitive behavioral therapy, occupational therapy, psychotropic medication, speech–language pathology |

| Frequency | Estimated 1 in 100 children (1%) worldwide[1] |

Autism, formally called autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or autism spectrum condition (ASC), is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by deficits in social communication and social interaction, and repetitive or restricted patterns of behaviors, interests, or activities, which can include hyper- and hyporeactivity to sensory input. Autism is clinically regarded as a spectrum disorder, meaning that it can manifest very differently in each person. For example, some are nonspeaking, while others have proficient spoken language. Because of this, there is wide variation in the support needs of people across the autism spectrum.

With autism now known to be a lifelong, unpreventable condition, many forms of therapy, such as speech and occupational therapy, have been developed that may help autistic people. Some forms of therapy, such as applied behavior analysis, have been shown to improve certain symptoms of autism, such as socialization, communication, expressive language, intellectual functioning, language development, and acquisition of daily living skills.

Psychiatry has traditionally classified autism as a mental disorder, but the autism rights movement and an increasing number of researchers see autism as part of neurodiversity, the natural diversity in human thinking and experience, with strengths, differences, and weaknesses. The understanding of autism has been shaped by cultural, scientific, and societal factors, and its perception and treatment change over time as scientific understanding of autism develops.

History

The term "autism" was first introduced by Eugen Bleuler, who first described of schizophrenia (a disorder that was previously known as dementia praecox) in 1911.[2] The diagnosis of schizophrenia at that time was broader than its modern equivalent, and autistic children were said to have childhood schizophrenia. Bleuler used the term "autism" to describe the situation of patients who had lost contact with reality, and who appeared to exist in their own fantasy world, unable to communicate with other people.

In the 1930s and 1940s, Leo Kanner and Hans Asperger described two related syndromes, later termed infantile autism and Asperger syndrome respectively. In 1943, Kanner published his landmark paper "Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact," describing 11 children who displayed "a powerful desire for aloneness" and "an obsessive insistence on persistent sameness."[3] Kanner took the term "autism," which Bleuler previously attributed to the inward, introspective symptoms typical in adult schizophrenia patients, and labeled the children in his study as having "infantile autism." He classified his description of "autism" to be independent from the psychotic disorder of schizophrenia, explaining how autism was not a precursor to schizophrenia, and that the symptoms of autism appeared evident and present at birth and early life.

Hans Asperger described an "autistic psychopathy of childhood" which he identified in over 200 children, with particular detailed descriptions of four young boys, who showed a pattern of behavior and skills including "lack of empathy, poor ability to make friends, unidirectional conversation, strong preoccupation with special interests, and awkward movements."[4] His symptoms described “a particularly interesting and highly recognizable type of child,” later called "Asperger syndrome" listed in the DSM-IV in 1994 as one of autism’s four subcategories.[5]

Although both Kanner and Asperger described conditions they believed to be distinct from schizophrenia, gormally, however, autistic children continued to be diagnosed under various terms related to schizophrenia in both the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and International Classification of Diseases (ICD). By the 1970s it had become more widely recognized that autism and schizophrenia were in fact distinct psychiatric conditions, and in 1980, this was formalized for the first time with new diagnostic categories in the DSM-III.[6] Asperger syndrome was introduced in the DSM-IV as a formal diagnosis in 1994, but in 2013, Asperger syndrome and infantile autism were reunified into a single diagnostic category, autism spectrum disorder (ASD).[7]

By the twenty-first century, some people on the autism spectrum, as well as a growing number of researchers, advocated a shift in attitudes away from the view that autism spectrum disorder is a disease that must be treated or cured toward the view that it is a part of neurodiversity, the natural diversity in human thinking and experience, with strengths, differences, and weaknesses.[8]

Classification

Before the DSM-5 (2013) and ICD-11 (2022) diagnostic manuals were adopted, what is now called ASD was found under the diagnostic category pervasive developmental disorder. The previous system relied on a set of closely related and overlapping diagnoses such as Asperger syndrome and Kanner syndrome. This created unclear boundaries between the terms, so for the DSM-5 and ICD-11, a spectrum approach was taken.

The DSM-5 and ICD-11 use different categorization tools to define this spectrum. DSM-5 uses a "level" system, which ranks how in need of support the patient is,[9] while the ICD-11 system has two axes, social communication and reciprocal social interactions and inflexible patterns of behavior, interests, or activities.[10]

Autism is currently defined as a highly variable neurodevelopmental disorder that is generally thought to cover a broad and deep spectrum, manifesting very differently from one person to another. Some have high support needs, may be non-speaking, and experience developmental delays; this is more likely with other co-existing diagnoses. Others have relatively low support needs; they may have more typical speech-language and intellectual skills but atypical social/conversation skills, narrowly focused interests, and wordy, pedantic communication. They may still require significant support in some areas of their lives.

The spectrum model should not be understood as a continuum running from mild to severe, but instead means that autism can present very differently in each person. How a person presents can depend on context, and may vary over time.

ICD

The World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases (11th Revision), ICD-11, was was adopted by the 72nd World Health Assembly in 2019 and came into full effect as of January 2022.[11] It describes ASD as follows:

Autism spectrum disorder is characterised by persistent deficits in the ability to initiate and to sustain reciprocal social interaction and social communication, and by a range of restricted, repetitive, and inflexible patterns of behaviour, interests or activities that are clearly atypical or excessive for the individual's age and sociocultural context. The onset of the disorder occurs during the developmental period, typically in early childhood, but symptoms may not become fully manifest until later, when social demands exceed limited capacities. Deficits are sufficiently severe to cause impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational or other important areas of functioning and are usually a pervasive feature of the individual's functioning observable in all settings, although they may vary according to social, educational, or other context. Individuals along the spectrum exhibit a full range of intellectual functioning and language abilities.[10]

DSM

The American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR), released in 2022, is the current version of the DSM.[12] It is the predominant mental health diagnostic system used in the United States and Canada, and is often used in Anglophone countries.

Its fifth edition, DSM-5, released in May 2013, was the first to define ASD as a single diagnosis, which is still the case in the DSM-5-TR. ASD encompasses previous diagnoses, including the four traditional diagnoses of autism—classic Kanner syndrome, Asperger syndrome, childhood disintegrative disorder, and pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS)—and the range of diagnoses that included the word "autism." Rather than distinguishing among these diagnoses, the DSM-5 and DSM-5-TR adopt a dimensional approach to diagnosing disorders that fall underneath the autism spectrum umbrella in one diagnostic category. Within this category, the DSM includes a framework that differentiates each person by dimensions of symptom severity, as well as by associated features (the presence of other disorders or factors that likely contribute to the symptoms, other neurodevelopmental or mental disorders, intellectual disability, or language impairment).[12]

The symptom domains are social communication and restricted, repetitive behaviors, with the option of a separate severity—the negative impact of the symptoms on the person—being specified for each domain, rather than an overall severity. Until 2013, deficits in social function and communication were considered two separate symptom domains. The current social communication domain criteria for autism diagnosis require people to have deficits across three social skills: social-emotional reciprocity, nonverbal communication, and developing and sustaining relationships. Further, the DSM-5 changed to an onset age "in the early developmental period," with a note that symptoms "may not become fully manifest until social communication demands exceed limited capacities," rather than the previous, more restricted three years of age.[13] These changes remain in the DSM-5-TR.

Symptoms and characteristics

For many people, autistic characteristics first appear during infancy or childhood and follow a steady course without remission. Autistic people may be severely impaired in some respects but average, or even superior, in others.[14][15]

There are many signs associated with autism, and the presentation varies widely.[16] The table below contains common signs:

Common signs for autistic spectrum disorder - avoidance of eye-contact

- little or no babbling as an infant

- not showing interest in indicated objects

- delayed language skills (e.g. having a smaller vocabulary than peers or difficulty expressing themselves in words)

- reduced interest in other children or caretakers, possibly with more interest in objects

- difficulty playing reciprocal games (e.g. peek-a-boo)

- hyper- or hypo-sensitivity to or unusual response to the smell, texture, sound, taste, or appearance of things

- resistance to changes in routine

- repetitive, limited, or otherwise unusual usage of toys (e.g. lining up toys)

- repetition of words or phrases (echolalia)

- repetitive motions or movements, including stimming

- self-harming

Social and communication skills

Autistic people display atypical nonverbal behaviors or show differences in nonverbal communication. They may make infrequent eye contact, even when called by name, or avoid it altogether. They often recognize fewer emotions and their meaning from others' facial expressions, and may not respond with facial expressions expected by their non-autistic peers.[17] At least half of autistic children have unusual prosody.[18]

Differences in verbal communication begin to be noticeable in childhood, as many autistic children develop language skills at an uneven pace. Verbal communication may be delayed or never develop (nonverbal autism), while reading ability may be present before school age (hyperlexia). Infants may show delayed onset of babbling, unusual gestures, diminished responsiveness, and vocal patterns that are not synchronized with the caregiver. In the second and third years, autistic children may have less frequent and less diverse babbling, consonants, words, and word combinations; their gestures are less often integrated with words. Autistic children are less likely to make requests or share experiences and more likely to simply repeat others' words (echolalia).[17] Autistic adults' verbal communication skills largely depend on when and how well speech is acquired during childhood.

Autistic people struggle to understand the social context and subtext of neurotypical conversational or printed situations, and form different conclusions about the content.[19] Temple Grandin, an autistic woman involved in autism activism, described her inability to understand neurotypicals' social communication as leaving her feeling "like an anthropologist from Mars."[20]

Historically, autistic children were said to be delayed in developing a theory of mind, and the empathizing–systemizing theory has argued that while autistic people have compassion (affective empathy) for others with similar presentation of symptoms, they have limited, though not necessarily absent, cognitive empathy. Based on findings that at a population level, females are stronger empathizers and males are stronger systemizers, the ‘‘extreme male brain’’ theory posits that autism represents an extreme of the male pattern (impaired empathizing and enhanced systemizing).[21] This may present as social naïvety,[22] lower than average intuitive perception of the utility or meaning of body language, social reciprocity, and/or social expectations, including the habitus, social cues, and/or some aspects of sarcasm.[12]

According to the medical model, autistic people experience social communications impairments. This deficit-based view predicts that autistic–autistic interaction would be less effective than autistic–non-autistic interactions or even non-functional.[23] Recent research has increasingly questioned these findings, as the "double empathy problem" theory argues that there is a lack of mutual understanding and empathy between both neurotypical persons and autistic individuals.[24][25]

However, research has found that autistic–autistic interactions are as effective in information transfer as interactions between non-autistics are, and that communication breaks down only between autistics and non-autistics:

Non-autistic people struggle to identify autistic mental states, identify autistic facial expressions, overestimate autistic egocentricity, and are less willing to socially interact with autistic people. Thus, although non-autistic people are generally characterised as socially skilled, these skills may not be functional, or effectively applied, when interacting with autistic people. [23]

Thus there has been a recent shift to acknowledge that autistic people may simply respond and behave differently than non-autistic people.

Restricted and repetitive behaviors

The second core symptom of ASD is a pattern of restricted and repetitive behaviors, activities, and interests. In order to be diagnosed with ASD under the DSM-5-TR, a person must have at least two of the following behaviors:[12]

- Repetitive behaviors – Repetitive behaviors such as rocking, hand flapping, finger flicking, head banging, or repeating phrases or sounds. These behaviors may occur constantly or only when the person gets stressed, anxious or upset. These behaviors are also known as "stimming."

- Resistance to change – A strict adherence to routines such as eating certain foods in a specific order or taking the same path to school every day. The person may become distressed if there is a change or disruption to their routine.

- Restricted interests – An excessive interest in a particular activity, topic, or hobby, and devoting all their attention to it. For example, young children might completely focus on things that spin and ignore everything else. Older children might try to learn everything about a single topic, such as the weather or sports, and perseverate or talk about it constantly.

- Sensory reactivity – An unusual reaction to certain sensory inputs, such as negative reaction to specific sounds or textures, fascination with lights or movements, or apparent indifference to pain or heat.

Self-injury

Self-injurious behaviors (SIB) are relatively common in autistic people, and can include head-banging, self-cutting, self-biting, and hair-pulling; some of these can result in serious injury or death.

- Frequency and/or continuation of self-injurious behavior can be influenced by environmental factors (such as reward for halting self-injurious behavior). However this does not apply to younger children with autism.

- Higher rates of self-injury are noted in socially isolated autistic people. This includes a suicide rate for verbal autistics that is nine times that of the general population.[26]

Other features

Autistic people may have symptoms that do not contribute to the official diagnosis, but that can affect the person or the family.[27]

- Some people with ASD show unusual or notable abilities, ranging from splinter skills (such as the memorization of trivia) to rare talents in mathematics, music, or artistic reproduction, which in exceptional cases are considered a part of the savant syndrome.[28][29][30] One study describes how some people with ASD show superior skills in perception and attention relative to the general population.[31] Sensory abnormalities are found in over 90% of autistic people, and are considered core features by some.[32]

- More generally, autistic people tend to show a "spiky skills profile", with strong abilities in some areas contrasting with much weaker abilities in others.[33]

- Differences between the previously recognized disorders under the autism spectrum are greater for under-responsivity (for example, walking into things) than for over-responsivity (for example, distress from loud noises) or for sensation seeking (for example, rhythmic movements).[34] An estimated 60–80% of autistic people have motor signs that include poor muscle tone, poor motor planning, and toe walking;[32][35] deficits in motor coordination are pervasive across ASD and are greater in autism proper.[36][37]

- Pathological demand avoidance can occur. People with this set of autistic symptoms are more likely to refuse to do what is asked or expected of them, even to activities they enjoy.

- Unusual or atypical eating behavior occurs in about three-quarters of children with ASD, to the extent that it was formerly a diagnostic indicator.[27] Selectivity is the most common problem, although eating rituals and food refusal also occur.[38]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of autism is based on a person's reported and directly observed behavior.[39] There are no known biomarkers for autism spectrum conditions that allow for a conclusive diagnosis.[40]

In most cases, diagnostic criteria codified in the World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases (ICD) or the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) are used. These reference manuals are regularly updated based on advances in research, systematic evaluation of clinical experience, and healthcare considerations. Currently, the DSM-5 published in 2013 and the ICD-10 that came into effect in 1994 are used, with the latter in the process of being replaced by the ICD-11 that came into effect in 2022 and is now implemented by healthcare systems across the world. Which autism spectrum diagnoses can be made and which criteria are used depends on the local healthcare system's regulations.

According to the DSM-5-TR (2022), in order to receive a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder, one must present with "persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction" and "restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities."[41] These behaviors must begin in early childhood and affect one's ability to perform everyday tasks. Furthermore, the symptoms must not be fully explainable by intellectual developmental disorder or global developmental delay.

Diagnostic process

There are several factors that make autism spectrum disorder difficult to diagnose. First off, there are no standardized imaging, molecular or genetic tests that can be used to diagnose ASD.[42] Additionally, there is a lot of variety in how ASD affects individuals. The behavioral manifestations of ASD depend on one's developmental stage, age of presentation, current support, and individual variability.[43][41] Lastly, there are multiple conditions that may present similarly to autism spectrum disorder, including intellectual disability, hearing impairment, a specific language impairment[44] such as Landau–Kleffner syndrome.[45] ADHD, anxiety disorder, and psychotic disorders.[46] Furthermore, the presence of autism can make it harder to diagnose coexisting psychiatric disorders such as depression.[47]

Ideally the diagnosis of ASD should be given by a team of clinicians (e.g. pediatricians, child psychiatrists, child neurologists) based on information provided from the affected individual, caregivers, other medical professionals and from direct observation.[48] Evaluation of a child or adult for autism spectrum disorder typically starts with a pediatrician or primary care physician taking a developmental history and performing a physical exam. If warranted, the physician may refer the individual to an ASD specialist who will observe and assess cognitive, communication, family, and other factors using standardized tools, and taking into account any associated medical conditions.[44]

The age at which ASD is diagnosed varies. Sometimes ASD can be diagnosed as early as 18 months, however, diagnosis of ASD before the age of two years may not be reliable.[42] Additionally, age of diagnosis may depend on the severity of ASD, with more severe forms of ASD more likely to be diagnosed at an earlier age.[49] Diagnosis of ASD in adults poses unique challenges because it still relies on an accurate developmental history and because autistic adults sometimes learn coping strategies, known as "masking" or "camouflaging", which may make it more difficult to obtain a diagnosis.[50][51]

Differences in behavioral presentation and gender-stereotypes may make it more challenging to diagnose autism spectrum disorder in a timely manner in females.[52][53] A notable percentage of autistic females may be misdiagnosed, diagnosed after a considerable delay, or not diagnosed at all.[53]

Screening

About half of parents of children with ASD notice their child's atypical behaviors by age 18 months, and about four-fifths notice by age 24 months.[54] If a child does not meet any of the following milestones, it "is an absolute indication to proceed with further evaluations. Delay in referral for such testing may delay early diagnosis and treatment and affect the [child's] long-term outcome."[27]

- No response to name (or gazing with direct eye contact) by 6 months.[55]

- No babbling by 12 months.

- No gesturing (pointing, waving, etc.) by 12 months.

- No single words by 16 months.

- No two-word (spontaneous, not just echolalic) phrases by 24 months.

- Loss of any language or social skills, at any age.

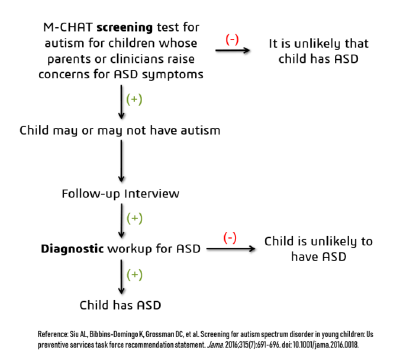

Screening tools include the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT), the Early Screening of Autistic Traits Questionnaire, and the First Year Inventory; initial data on M-CHAT and its predecessor, the Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (CHAT), on children aged 18–30 months suggests that it is best used in a clinical setting and that it has low sensitivity (many false-negatives) but good specificity (few false-positives).[54] It may be more accurate to precede these tests with a broadband screener that does not distinguish ASD from other developmental disorders.[56] Screening tools designed for one culture's norms for behaviors like eye contact may be inappropriate for a different culture.[57] Although genetic screening for autism is generally still impractical, it can be considered in some cases, such as children with neurological symptoms and dysmorphic features.[58]

Misdiagnosis

There is a significant level of misdiagnosis of autism in neurodevelopmentally typical children; 18–37% of children diagnosed with ASD eventually lose their diagnosis. This high rate of lost diagnosis cannot be accounted for by successful ASD treatment alone. The most common reason parents reported as the cause of lost ASD diagnosis was new information about the child (73.5%), such as a replacement diagnosis. Other reasons included a diagnosis given so the child could receive ASD treatment (24.2%), ASD treatment success or maturation (21%), and parents disagreeing with the initial diagnosis (1.9%).[59]

Many of the children who were later found not to meet ASD diagnosis criteria then received diagnosis for another developmental disorder. Most common was ADHD, but other diagnoses included sensory disorders, anxiety, personality disorder, or learning disability.[59]Template:Primary source inline Neurodevelopment and psychiatric disorders that are commonly misdiagnosed as ASD include specific language impairment, social communication disorder, anxiety disorder, reactive attachment disorder, cognitive impairment, visual impairment, hearing loss and normal behavioral variation.[60] Some behavioral variations that resemble autistic traits are repetitive behaviors, sensitivity to change in daily routines, focused interests, and toe-walking. These are considered normal behavioral variations when they do not cause impaired function. Boys are more likely to exhibit repetitive behaviors especially when excited, tired, bored, or stressed. Some ways of distinguishing typical behavioral variations from autistic behaviors are the ability of the child to suppress these behaviors and the absence of these behaviors during sleep.[48]

Possible causes

Exactly what causes autism remains unknown.[61][62][63][64] It was long mostly presumed that there is a common cause at the genetic, cognitive, and neural levels for the social and non-social components of ASD's symptoms, described as a triad in the classic autism criteria.[65] But it is increasingly suspected that autism is instead a complex disorder whose core aspects have distinct causes that often cooccur.[65][66] While it is unlikely that ASD has a single cause,[66] many risk factors identified in the research literature may contribute to ASD development. These include genetics, prenatal and perinatal factors (meaning factors during pregnancy or very early infancy), neuroanatomical abnormalities, and environmental factors. It is possible to identify general factors, but much more difficult to pinpoint specific ones. Given the current state of knowledge, prediction can only be of a global nature and therefore requires the use of general markers.[67]

Comorbid conditions

Autism is correlated or comorbid with several personality traits/disorders.[68] Comorbidity may increase with age and may worsen the course of youth with ASDs and make intervention and treatment more difficult. Distinguishing between ASDs and other diagnoses can be challenging because the traits of ASDs often overlap with symptoms of other disorders, and the characteristics of ASDs make traditional diagnostic procedures difficult.[69][70]

Some comorbid conditions are the following:

- The most common medical condition occurring in people with ASDs is seizure disorder or epilepsy, which occurs in 11–39% of autistic people.[71] The risk varies with age, cognitive level, and type of language disorder.[72]

- Intellectual disabilities are some of the most common comorbid disorders with ASDs. As diagnosis is increasingly being given to people with higher functioning autism, there is a tendency for the proportion with comorbid intellectual disability to decrease over time. In a 2019 study, it was estimated that approximately 30-40% of people diagnosed with ASD also have intellectual disability.[73]

- Learning disabilities are also highly comorbid in people with an ASD. Approximately 25–75% of people with an ASD also have some degree of a learning disability.[74]

- Various anxiety disorders tend to co-occur with ASDs, with overall comorbidity rates of 7–84%.[75]

- Rates of comorbid depression in people with an ASD range from 4–58%.[76]

- Deficits in ASD are often linked to behavior problems, such as difficulties following directions, being cooperative, and doing things on other people's terms.[77] Symptoms similar to those of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) can be part of an ASD diagnosis.[78]

- Sensory processing disorder is also comorbid with ASD, with comorbidity rates of 42–88%.[79]

- Gastrointestinal problems are one of the most commonly co-occurring medical conditions in autistic people.[80] These are linked to greater social impairment, irritability, language impairments, mood changes, and behavior and sleep problems.

- Sleep problems affect about two-thirds of people with ASD at some point in childhood. These most commonly include symptoms of insomnia, such as difficulty falling asleep, frequent nocturnal awakenings, and early morning awakenings. Sleep problems are associated with difficult behaviors and family stress, and are often a focus of clinical attention over and above the primary ASD diagnosis.[81]

Prognosis

There is no evidence of a cure for autism.[82][68] The degree of symptoms can decrease, occasionally to the extent that people lose their diagnosis of ASD;[83][84] this occurs sometimes after intensive treatment[85] and sometimes not. It is not known how often this outcome happens,[86] with reported rates in unselected samples ranging from 3% to 25%.[83][84] Although core difficulties tend to persist, symptoms often become less severe with age.[87] Acquiring language before age six, having an IQ above 50, and having a marketable skill all predict better outcomes; independent living is unlikely in autistic people with higher support needs.[88]

The prognosis of autism describes the developmental course, gradual autism development, regressive autism development, differential outcomes, academic performance and employment.

Management

There is no treatment as such for autism,[89] and many sources advise that this is not an appropriate goal,[90][91] although treatment of co-occurring conditions remains an important goal.[92] There is no cure for autism as of 2023, nor can any of the known treatments significantly reduce brain mutations caused by autism, although those who require little to no support are more likely to experience a lessening of symptoms over time.[93][94][95] Several interventions can help children with autism,[96] and no single treatment is best, with treatment typically tailored to the child's needs.[82] Studies of interventions have methodological problems that prevent definitive conclusions about efficacy,[97] but the development of evidence-based interventions has advanced.[98]

The main goals of treatment are to lessen associated deficits and family distress, and to increase quality of life and functional independence. In general, higher IQs are correlated with greater responsiveness to treatment and improved treatment outcomes.[99][100] Behavioral, psychological, education, and/or skill-building interventions may be used to assist autistic people to learn life skills necessary for living independently,[101] as well as other social, communication, and language skills. Therapy also aims to reduce challenging behaviors and build upon strengths.[102]

Intensive, sustained special education programs and behavior therapy early in life may help children acquire self-care, language, and job skills.[82] Although evidence-based interventions for autistic children vary in their methods, many adopt a psychoeducational approach to enhancing cognitive, communication, and social skills while minimizing problem behaviors. While medications have not been found to help with core symptoms, they may be used for associated symptoms, such as irritability, inattention, or repetitive behavior patterns.[103]

Non-pharmacological interventions

Intensive, sustained special education or remedial education programs and behavior therapy early in life may help children acquire self-care, social, and job skills. Available approaches include applied behavior analysis, developmental models, structured teaching, speech and language therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy,[104] social skills therapy, and occupational therapy.[105] Among these approaches, interventions either treat autistic features comprehensively, or focus treatment on a specific area of deficit.[100] Generally, when educating those with autism, specific tactics may be used to effectively relay information to these people. Using as much social interaction as possible is key in targeting the inhibition autistic people experience concerning person-to-person contact. Additionally, research has shown that employing semantic groupings, which involves assigning words to typical conceptual categories, can be beneficial in fostering learning.[106]

ASD treatment generally focuses on behavioral and educational interventions to target its two core symptoms: social communication deficits and restricted, repetitive behaviors.[107] If symptoms continue after behavioral strategies have been implemented, some medications can be recommended to target specific symptoms or co-existing problems such as restricted and repetitive behaviors (RRBs), anxiety, depression, hyperactivity/inattention and sleep disturbance.[107] Melatonin, for example, can be used for sleep problems.[108]

Several parent-mediated behavioral therapies target social communication deficits in children with autism, but their efficacy in treating RRBs is uncertain.[109]

Education

Educational interventions often used include applied behavior analysis (ABA), developmental models, structured teaching, speech and language therapy and social skills therapy.[82] Among these approaches, interventions either treat autistic features comprehensively, or focalize treatment on a specific area of deficit.[98]

Pharmacological interventions

Medications may be used to treat ASD symptoms that interfere with integrating a child into home or school when behavioral treatment fails.[111] They may also be used for associated health problems, such as ADHD, anxiety, or if the person is hurting themself or aggressive with others,[111][112] but their routine prescription for ASD's core features is not recommended.[113]

More than half of US children diagnosed with ASD are prescribed psychoactive drugs or anticonvulsants, with the most common drug classes being antidepressants, stimulants, and antipsychotics.[114][115] SSRI antidepressants, such as fluoxetine and fluvoxamine, have been shown to be effective in reducing repetitive and ritualistic behaviors, while the stimulant medication methylphenidate is beneficial for some children with co-morbid inattentiveness or hyperactivity.[82]

There is scant reliable research about the effectiveness or safety of drug treatments for adolescents and adults with ASD.[116] No known medication relieves autism's core symptoms of social and communication impairments.[103]

Alternative medicine

A multitude of researched alternative therapies have also been implemented. Many have resulted in harm to autistic people.[105] A 2020 systematic review on adults with autism has provided emerging evidence for decreasing stress, anxiety, ruminating thoughts, anger, and aggression through mindfulness-based interventions for improving mental health.[117]

Results of a systematic review on interventions to address health outcomes among autistic adults found emerging evidence to support mindfulness-based interventions for improving mental health. This includes decreasing stress, anxiety, ruminating thoughts, anger, and aggression.[118] An updated Cochrane review (2022) found evidence that music therapy likely improves social interactions, verbal communication, and nonverbal communication skills.[119] There has been early research on hyperbaric treatments in children with autism.[120] Studies on pet therapy have shown positive effects.[121]

Epidemiology

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates about 1 in 100 children had autism during the period from 2012 to 2021 as that was the average estimate in studies published during that period with a trend of increasing prevalence over time. They note however, that this estimate represents an average figure, and reported prevalence varies substantially across studies. The prevalence of autism in many low- and middle-income countries is unknown.[1] The number of people diagnosed has increased considerably since the 1990s, which may be partly due to increased recognition of the condition.[122]

While rates of ASD are consistent across cultures, they vary greatly by gender, with boys diagnosed far more frequently than girls: ASD is more than 4 times more common among boys than among girls.[123]

Society and culture

An autistic culture has emerged, accompanied by the autistic rights and neurodiversity movements, that argues autism should be accepted as a difference to be accommodated instead of cured,[124][125][126][127][128] although a minority of autistic people might still accept a cure.[129] Worldwide, events related to autism include World Autism Awareness Day, Autism Sunday, Autistic Pride Day, Autreat, and others.[130][131][132][133]

Social-science scholars study those with autism in hopes to learn more about "autism as a culture, transcultural comparisons ... and research on social movements."[134] Many autistic people have been successful in their fields.[135]

Neurodiversity movement

Some autistic people, as well as a growing number of researchers,[136] have advocated a shift in attitudes toward the view that autism spectrum disorder is a difference, rather than a disease that must be treated or cured.[137][138] Critics have bemoaned the entrenchment of some of these groups' opinions.[139][140][141][142]

The neurodiversity movement and the autism rights movement are social movements within the context of disability rights, emphasizing the concept of neurodiversity, which describes the autism spectrum as a result of natural variations in the human brain rather than a disorder to be cured.[126][143] The autism rights movement advocates for including greater acceptance of autistic behaviors; therapies that focus on coping skills rather than imitating the behaviors of those without autism;[144] and the recognition of the autistic community as a minority group.[144][145]

Symbols and flags

Over the years, multiple organizations have tried to capture the essence of autism in symbols. In 1963, the board for the National Autistic Society, led by Gerald Gasson, proposed the "puzzle piece" as a symbol for autism, because it fit their view of autism as a "puzzling condition".[146] In 1999, the Autism Society adopted the puzzle ribbon as the universal sign of autism awareness.[146] In 2004, neurodiversity advocates Amy and Gwen Nelson conjured the "rainbow infinity symbol". It was initially the logo for their website, Aspies for Freedom. Nowadays, the prismatic colors are often associated with the neurodiversity movement in general.[147] The autistic spectrum has also been symbolized by the infinity symbol itself.[148] In 2018, Julian Morgan wrote the article "Light It Up Gold", a response to Autism Speaks's "Light It Up Blue" campaign, launched in 2007.[149][150] Aurum is Latin for gold,[147] and gold has been used to symbolize autism, since both words start with "Au". Though a consensus for a flag to unite autism and neurodiversity has not yet been established, one has gained traction on Reddit.[151] The flag implements a gradient to represent the Pride Movement and incorporates a golden infinity symbol as its focal point.[152] While flags are symbols of solidarity, they may trigger negative associations, such as apparent rivalry among two or more flags.[153] For this reason, flags are sought that can be tailored to the personal preferences of any neurotype.[154][155]

Caregivers

Families who care for an autistic child face added stress from a number of different causes.[156][157] Parents may struggle to understand the diagnosis and to find appropriate care options. They often take a negative view of the diagnosis, and may struggle emotionally.[158] More than half of parents over age 50 are still living with their child, as about 85% of autistic people have difficulties living independently.[159] Some studies also find decreased earnings among parents who care for autistic children.[160][161] Siblings of children with ASD report greater admiration and less conflict with the affected sibling than siblings of unaffected children, like siblings of children with Down syndrome. But they reported lower levels of closeness and intimacy than siblings of children with Down syndrome; siblings of people with ASD have a greater risk of negative well-being and poorer sibling relationships as adults.[162]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Autism World Health Organization (November 15, 2023). Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ↑ Eugen Bleuler, Joseph Zinkin (trans.), Dementia Praecox or The Group of Schizophrenias (International Universities Press, 1950 (original 1911).

- ↑ Leo Kanner, Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact Nervous Child 35 (4): 100–136. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ↑ Hans Asperger, “‘Autistic Psychopathy’ in Childhood,” in Autism and Asperger Syndrome edited by Uta Frith (Cambridge University Press, 1991, ISBN 978-0521386081), 37-92. Originally published as “Die ‘Autistischen Psychopathen’ im Kindesalter,” Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankenheiten 117 (1944):76-136.

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-IV, 4th ed. (Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994, ISBN 0890420610).

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association, DSM-III: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 1980, ISBN 978-0521315289).

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition: DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013, ISBN 978-0890425541).

- ↑ Andrew Solomon, The Autism Rights Movement The New Yorker (May 23, 2008). Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ↑ Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): Diagnostic Criteria CDC (November 2, 2022). Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 6A02 Autism spectrum disorder: Diagnostic Requirements ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics (January 2023). Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ↑ ICD-11 World Health Organization. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition Text Revision: DSM-5-TR (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2022, ISBN 0890425760).

- ↑ DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria: Autism Spectrum Disorder Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee (IACC), U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ↑ Louise Cummings (ed.) Handbook of Pragmatic Language Disorders (Springer, 2021, ISBN 978-3030749842).

- ↑ Jill Boucher, Autism Spectrum Disorders (SAGE Publications Ltd, 2022, ISBN 978-1529744651).

- ↑ Autism: Signs and symptoms Public Health Agency of Canada (April 7, 2022). Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Autism Spectrum Disorder: Communication Problems in Children National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (April 13, 2020). Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ↑ Riccardo Fusaroli, Anna Lambrechts, Dan Bang, Dermot M. Bowler, and Sebastian B. Gaigg, "Is voice a marker for Autism spectrum disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis" Autism Research 10(3) (2017):384–407. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ↑ Beverly Vicker, Social communication and language characteristics associated with high-functioning, verbal children and adults with autism spectrum disorder Indiana Resource Center for Autism. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ↑ David Cohen, Temple Grandin: 'I'm an anthropologist from Mars' The Guardian (October 25, 2005). Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ↑ Simon Baron-Cohen, Rebecca C. Knickmeyer, and Matthew K. Belmonte, Sex differences in the brain: implications for explaining autism Science 310(5749) (November 4, 2005): 819–823. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ↑ James C. McPartland, Ami Klin, and Fred R. Volkmar (eds.), Asperger Syndrome: Assessing and Treating High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorders (The Guilford Press, 2014, ISBN 978-1462514144).

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Catherine J. Crompton et al., Autistic peer-to-peer information transfer is highly effective Autism 24(7) (May 20, 2020):1704–1712. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ↑ Damian E.M. Milton, On the ontological status of autism: the 'double empathy problem' Disability & Society 27(6) (October 2012):883–887. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ↑ Damian Milton, Emine Gurbuz, and Beatriz López, The 'double empathy problem': Ten years on Autism 26(8) (November, 2022):1901–1903. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ↑ Amelia Hill, Autism could be seen as part of personality for some diagnosed, experts say The Guardian (July 31, 2023). Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 (December 1999) The screening and diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 29 (6): 439–484. This paper represents a consensus of representatives from nine professional and four parent organizations in the US.

- ↑ (May 2009) The savant syndrome: an extraordinary condition. A synopsis: past, present, future. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 364 (1522): 1351–1357.

- ↑ (April 2018) [Neurobiological mechanisms of autistic savant and acquired savant]. Sheng Li Xue Bao 70 (2): 201–210.

- ↑ (October 2018) Savant syndrome has a distinct psychological profile in autism. Molecular Autism 9.

- ↑ (May 2009) Perception and apperception in autism: rejecting the inverse assumption. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 364 (1522): 1393–1398.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 (2009). Advances in autism. Annual Review of Medicine 60: 367–380.

- ↑ (August 1996) The neuropsychology of autism. Brain 119 (4): 1377–1400.

- ↑ (January 2009) A meta-analysis of sensory modulation symptoms in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 39 (1): 1–11.

- ↑ (10 January 2022)Automatic Assessment of Motor Impairments in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review. Cognitive Computation 14 (2): 624–659.

- ↑ (October 2010) Motor coordination in autism spectrum disorders: a synthesis and meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 40 (10): 1227–1240.

- ↑ (2022) Gross motor impairment and its relation to social skills in autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and two meta-analyses.. Psychological Bulletin 148 (3–4): 273–300.

- ↑ (2007). Atypical behaviors in children with autism and children with a history of language impairment. Research in Developmental Disabilities 28 (2): 145–162.

- ↑ (August 2003) Diagnosis of autism. BMJ 327 (7413): 488–493.

- ↑ (2022) The Lancet Commission on the future of care and clinical research in autism. The Lancet 399 (10321): 271–334.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 (2022) "Section 2: Neurodevelopmental Disorders", Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5-TR, Fifth edition, text revision., Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ISBN 978-0-89042-575-6.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 CDC (31 March 2022). Screening and Diagnosis | Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) | NCBDDD (in en-us).

- ↑ (December 1999) Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children, adolescents, and adults with autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Working Group on Quality Issues. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 38 (12 Suppl): 32S–54S.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedDover2007 - ↑ (May 2000) Autistic regression and Landau-Kleffner syndrome: progress or confusion?. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 42 (5): 349–353.

- ↑ (March 2016)Diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder: reconciling the syndrome, its diverse origins, and variation in expression. The Lancet. Neurology 15 (3): 279–91.

- ↑ (2009). Cormorbidity: diagnosing comorbid psychiatric conditions. Psychiatric Times 26 (4).

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 (February 2017) When Autistic Behavior Suggests a Disease Other than Classic Autism. Pediatric Clinics of North America 64 (1): 127–138.

- ↑ (December 2005) Factors associated with age of diagnosis among children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 116 (6): 1480–1486.

- ↑ (August 2020) Diagnosis of autism in adulthood: A scoping review. Autism 24 (6): 1311–1327.

- ↑ 6A02 Autism spectrum disorder..

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:3 - ↑ 53.0 53.1 (29 October 2020) Barriers to Autism Spectrum Disorder Diagnosis for Young Women and Girls: a Systematic Review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 8 (4): 454–470.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedLand2008 - ↑ Autism case training part 1: A closer look – key developmental milestones. CDC.gov (18 August 2016).

- ↑ (September 2008) Validation of the Infant-Toddler Checklist as a broadband screener for autism spectrum disorders from 9 to 24 months of age. Autism 12 (5): 487–511.

- ↑ (May 2008) The challenge of screening for autism spectrum disorder in a culturally diverse society. Acta Paediatrica 97 (5): 539–540.

- ↑ (January 2009) Autistic phenotypes and genetic testing: state-of-the-art for the clinical geneticist. Journal of Medical Genetics 46 (1): 1–8.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedBlumberg 2016 - ↑ Conditions That May Look Like Autism, but Aren't. WebMD.

- ↑ (2022) in Johnny L. Matson: Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorder: assessment, diagnosis, and treatment, Autism and Child Psychopathology Series (in en). Cham: Springer Nature. DOI:10.1007/978-3-030-88538-0. ISBN 978-3-030-88538-0. OCLC 1341298051. “To date no one genetic feature or environmental cause has proven etiological in explaining most cases autism or has been able to account for rising rates of autism.”

- ↑ (2021) "Autism Spectrum Disorders: Etiology and Pathology", Autism spectrum disorders, Andreas M. Grabrucker (in en), Brisbane, Australia: Exon Publications, 1–16. DOI:10.36255/exonpublications.autismspectrumdisorders.2021.etiology. ISBN 978-0-6450017-8-5. OCLC 1280592589. “The cause of ASD is unknown, but several genetic and non-genetic risk factors have been characterized that, alone or in combination, are implicated in the development of ASD.”

- ↑ (2018). Focus on the Social Aspect of Autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 48 (5): 1861–1867.

- ↑ (2019). Where is the Evidence? A Narrative Literature Review of the Treatment Modalities for Autism Spectrum Disorders. Cureus 11 (1): e3901.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 (December 2008) The 'fractionable autism triad': a review of evidence from behavioural, genetic, cognitive and neural research. Neuropsychology Review 18 (4): 287–304.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 (October 2006) Time to give up on a single explanation for autism. Nature Neuroscience 9 (10): 1218–1220.

- ↑ (2010). The origins of social impairments in autism spectrum disorder: studies of infants at risk. Neural Networks 23 (8–9): 1072–6.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedLevy 2009 - ↑ (2011) "Psychiatric Disorders in People with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Phenomenology and Recognition", International handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders. New York: Springer, 53–74. ISBN 978-1-4419-8064-9. OCLC 746203105.

- ↑ (September 2010) Mental health of adults with autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disability. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 23 (5): 421–6.

- ↑ (2000). Epilepsy and epileptiform EEG: association with autism and language disorders. Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews 6 (4): 300–8.

- ↑ (June 2009) The role of epilepsy and epileptiform EEGs in autism spectrum disorders. Pediatric Research 65 (6): 599–606.

- ↑ (2019) Autism and Intellectual Disability: A Systematic Review of Sexuality and Relationship Education. Sexuality and Disability 37 (3): 353–382.

- ↑ (June 2004) Autism and learning disability. Autism 8 (2): 125–40.

- ↑ (2003) Child Psychopathology. New York: The Guilford Press, 409–454. ISBN 978-1-57230-609-7.

- ↑ (1999). Psychiatric problems in individuals with autism, their parents and siblings. International Review of Psychiatry 11 (4): 278–298.

- ↑ (July 2007)Behaviour management problems as predictors of psychotropic medication and use of psychiatric services in adults with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 37 (6): 1080–5.

- ↑ (March 2010) Shared heritability of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 19 (3): 281–95.

- ↑ (October 2002) Efficacy of sensory and motor interventions for children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 32 (5): 397–422.

- ↑ (June 2018) Serotonin as a link between the gut-brain-microbiome axis in autism spectrum disorders. Pharmacological Research 132: 1–6.

- ↑ (December 2009) Sleep problems in autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, nature, & possible biopsychosocial aetiologies. Sleep Medicine Reviews 13 (6): 403–411.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 82.3 82.4 (November 2007) Management of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 120 (5): 1162–1182.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 (December 2008) Can children with autism recover? If so, how?. Neuropsychology Review 18 (4): 339–366.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 (February 2013) Optimal outcome in individuals with a history of autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 54 (2): 195–205.

- ↑ (May 2014) Intervention for optimal outcome in children and adolescents with a history of autism. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 35 (4): 247–256.

- ↑ (January 2008) Evidence-based comprehensive treatments for early autism. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology 37 (1): 8–38.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedRapin - ↑ (September 2003) Diagnosis and epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 48 (8): 517–525.

- ↑ Fake and harmful autism 'treatments' (in en) (2 May 2019).

- ↑ Making information and the words we use accessible.

- ↑ How to talk about autism (in en).

- ↑ The psychiatric management of autism in adults (CR228) (in en).

- ↑ (October 2006) Asperger's syndrome. Adolescent Medicine Clinics 17 (3): 771–88; abstract xiii.

- ↑ (June 2008)Asperger syndrome. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 18 (1): 2–11.

- ↑ (July 2005) Modeling clinical outcome of children with autistic spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 116 (1): 117–22.

- ↑ 10 Facts about Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) (in en).

- ↑ (2008). Behavioural and developmental interventions for autism spectrum disorder: a clinical systematic review. PLOS ONE 3 (11): e3755.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 (2 November 2015) Evidence Base Update for Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology 44 (6): 897–922.

- ↑ (May 2009) Meta-analysis of Early Intensive Behavioral Intervention for children with autism. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology 38 (3): 439–450.

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedSmith - ↑ (November 2009) The effect of Autism Spectrum Disorders on adaptive independent living skills in adults with severe intellectual disability. Research in Developmental Disabilities 30 (6): 1203–1211.

- ↑ NIMH » Autism Spectrum Disorder. National Institutes of Health (US).

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 (March 2015) An update on pharmacotherapy for autism spectrum disorder in children and adolescents. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 28 (2): 91–101.

- ↑ (May 2021) Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics 147 (5).

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 (November 2007)Management of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 120 (5): 1162–1182.

- ↑ (2002) Children with Autism: A Developmental Perspective. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 178–179. ISBN 978-0-674-05313-7.

- ↑ 107.0 107.1 Autism spectrum disorder in children and adolescents: Pharmacologic interventions (March 2020).

- ↑ (March 2020) Practice guideline: Treatment for insomnia and disrupted sleep behavior in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 94 (9): 392–404.

- ↑ (August 2015) Evidence-based, parent-mediated interventions for young children with autism spectrum disorder: The case of restricted and repetitive behaviors. Autism 19 (6): 662–72.

- ↑ (August 2004) Opening a window to the autistic brain. PLOS Biology 2 (8): E267.

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 (December 2016) Autism Spectrum Disorder: Primary Care Principles. American Family Physician 94 (12): 972–979.

- ↑ (2023-10-09) Pharmacological intervention for irritability, aggression, and self-injury in autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2023 (10): CD011769.

- ↑ (2022) Pharmacological and dietary-supplement treatments for autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Molecular Autism 13 (1).

- ↑ (June 2007) Medication use among children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 17 (3): 348–355.

- ↑ (September 2012) Pharmacologic treatments for the behavioral symptoms associated with autism spectrum disorders across the lifespan. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 14 (3): 263–279.

- ↑ (2007). Systematic review of the effectiveness of pharmacological treatments for adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice 11 (4): 335–348.

- ↑ (August 2020) Interventions to address health outcomes among autistic adults: A systematic review. Autism 24 (6): 1345–1359.

- ↑ (August 2020) Interventions to address health outcomes among autistic adults: A systematic review. Autism 24 (6): 1345–1359.

- ↑ (May 2022) Music therapy for autistic people. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2022 (5): CD004381.

- ↑ {{#invoke:citation/CS1|citation |CitationClass=report }}Template:Update inline

- ↑ (November 2017) Reflections on Recent Research Into Animal-Assisted Interventions in the Military and Beyond. Current Psychiatry Reports 19 (12).

- ↑ G. Russell, S. Stapley, T. Newlove-Delgado, A. Salmon, R. White, F. Warren, A. Pearson, and T. Ford, "Time trends in autism diagnosis over 20 years: a UK population-based cohort study" Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 63(6) (August 2021):674–682.

- ↑ Autism spectrum disorder (ASD): How Often ASD Occurs Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (December 9, 2022). Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ↑ Autism Movement Seeks Acceptance, Not Cures. NPR (26 June 2006).

- ↑ Autistic and proud of it. Reed Elsevier.

- ↑ 126.0 126.1 "The autism rights movement", New York, 25 May 2008.

- ↑ (1917) The Economic World. New York city: Chronicle Publishing Company.

- ↑ (2008). Fieldwork on another planet: social science perspectives on the autism spectrum. BioSocieties 3 (3): 325–341.

- ↑ Results and Analysis of the Autistic Not Weird 2022 Autism Survey - Autistic Not Weird (in en-GB) (23 March 2022).

- ↑ World Autism Awareness Day, 2 April. United Nations.

- ↑ Autistic Pride Day 2015: A Message to the Autistic Community (18 June 2015).

- ↑ Autism Sunday – Home (2010).

- ↑ About Autreat. Autreat.com (2013).

- ↑ (2008). Fieldwork on Another Planet: Social Science Perspectives on the Autism Spectrum. BioSocieties 3 (3): 325–341.

- ↑ (13 April 2019) Mapping the Autistic Advantage from the Accounts of Adults Diagnosed with Autism: A Qualitative Study. Autism in Adulthood 1 (2): 124–133.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedPellicano - ↑ (2007). 'Surplus suffering': differences between organizational understandings of Asperger's syndrome and those people who claim the 'disorder'. Disability & Society 22 (7): 761–76.

- ↑ (2002). Is Asperger syndrome necessarily viewed as a disability?. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl 17 (3): 186–91. A preliminary, freely readable draft, with slightly different wording in the quoted text, is in: Is Asperger's syndrome necessarily a disability?. Autism Research Centre (2002).

- ↑ The Autism Rights Movement (23 May 2008).

- ↑ (1 October 2016)Autism spectrum disorder: difference or disability?. The Lancet Neurology 15 (11).

- ↑ (1 September 2008) Fieldwork on Another Planet: Social Science Perspectives on the Autism Spectrum. BioSocieties 3 (3): 325–341.

- ↑ "A medical condition or just a difference? The question roils autism community.". (written in en-US)

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedauto - ↑ 144.0 144.1 Should Autism Be Cured or Is "Curing" Offensive? (10 July 2016).

- ↑ (March 2012)Autism as a natural human variation: reflections on the claims of the neurodiversity movement. Health Care Analysis 20 (1): 20–30.

- ↑ 146.0 146.1 Solomon, Debra (2018-05-02). The History of the Autism Puzzle Piece Ribbon | Autism Career Coach Queens (in en-US).

- ↑ 147.0 147.1 Morgan, Julian (2018-03-11). Going Gold For Autism Acceptance (in en).

- ↑ Muzikar, Debra (2019-04-20). The Autism Puzzle Piece: A symbol that's going to stay or go? (in en-US).

- ↑ Willingham, Emily. No Foolin': Forget About Autism Awareness And Lighting Up Blue (in en).

- ↑ Franco, Janelle (2014). Puzzle Piece Project and Autism Awareness Month. Autism Speaks.

- ↑ There have been multiple conversations about the flag on Reddit. Take for example: Reddit (2019). "I tried creating an autism/neurodiversity flag. It's a work in progress"" Reddit (2022). "Autism pride flag goes hard". Reddit (2022). "where did this flag even come from? first time i ever saw it was during r/place, now i see it everywhere".

- ↑ AU-TI (2021). A New Autistic Pride Flag Has Suddenly Appeared & It's Amazing.

- ↑ Shanafelt, Robert (September 2008). The nature of flag power: How flags entail dominance, subordination, and social solidarity. Politics and the Life Sciences 27 (2): 13–27.

- ↑ (2003). Identifying customer need patterns for customization and personalization. Integrated Manufacturing Systems 14 (5): 387–396.

- ↑ (2006-03-01)The Psychological Appeal of Personalized Content in Web Portals: Does Customization Affect Attitudes and Behavior?. Journal of Communication 56 (1): 110–132.

- ↑ (2014) box|ambox}}&pg=PA301 Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders: Volume Two: Assessment, Interventions, and Policy, 4th, Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-28220-5. OCLC 946133861.

- ↑ (March 2019)Parenting a child with autism. Jornal Brasileiro de Psiquiatria 68 (1): 42–47.

- ↑ "An Alternative-Medicine Believer's Journey Back to Science", 29 April 2015.

- ↑ (September 2012) Parent and family impact of autism spectrum disorders: a review and proposed model for intervention evaluation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 15 (3): 247–77.

- ↑ (April 2008)Association of childhood autism spectrum disorders and loss of family income. Pediatrics 121 (4): e821–e826.

- ↑ (July 2008)Child care problems and employment among families with preschool-aged children with autism in the United States. Pediatrics 122 (1): e202–e208.

- ↑ (2007). Siblings of individuals with autism spectrum disorders across the life course. Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews 13 (4): 313–320.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-III: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd Edition. American Psychiatric Association, 1980. ISBN 978-0521315289

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-IV, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994. ISBN 0890420610

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013. ISBN 978-0890425541

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition Text Revision: DSM-5-TR. American Psychiatric Publishing, 2022. ISBN 0890425760

- Boucher, Jill. Autism Spectrum Disorders. SAGE Publications Ltd, 2022. ISBN 978-1529744651

- Cummings, Louise (ed.). Handbook of Pragmatic Language Disorders. Springer, 2021. ISBN 978-3030749842

- Frith, Uta. Autism and Asperger Syndrome. Cambridge University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0521386081

- McPartland, James C., Ami Klin, and Fred R. Volkmar (eds.). Asperger Syndrome: Assessing and Treating High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorders. The Guilford Press, 2014. ISBN 978-1462514144

External links

All links retrieved

- Autism World Health Organization (WHO)

- Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- Autism Spectrum Disorder National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)

- What Is Autism? Autism Speaks

- What Is Autism Spectrum Disorder? American Psychiatric Association

- Autism spectrum disorder Mayo Clinic

- Autism Spectrum Disorder Cleveland Clinic

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.