Scandinavian Peninsula

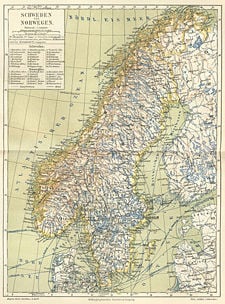

The Scandinavian Peninsula is a large peninsula in Northern Europe, consisting principally of the mainland territories of Norway and Sweden. A small part of northwestern Finland is sometimes also considered part of the peninsula. It is part of the larger Fennoscandia region which includes the Kola Peninsula, Karelia and Finland.

It is the largest peninsula in Europe at about 1,150 miles (1,850 km) in length, varying 230-500 miles (370â805 km) in width, covering 289,500 sq mi (750,000 sq km), .

The peninsula is bounded by the Barents Sea of the Arctic Ocean on the north, the Kattegat and Skagerrak Seas on the south, the Norwegian Sea and North Sea on the west, and the Baltic Sea, Gulf of Bothnia and Bay of Bothnia on the east.

The Scandinavian mountain range, part of the ancient Baltic Shield, forms the border between Norway and Sweden. In Norway the mountains reach the coastline and are deeply dissected by fjords. The eastern side of the range lies in Sweden and has extensive slopes of gentle gradient down to the Baltic Sea, and consists mostly of flat, heavily forested land dotted with lakes.

The region known as Scandinavia is centered on the Scandinavian Peninsula. As a linguistics, cultural, and historic area, it covers a more inclusive range of Northern Europe. The countries of the peninsula consistently rank high on a number of international analysis and monitoring systems in such areas as foreign policy, environmental sustainability, global competitiveness, technological advancement, education, freedom of the press, human development, health, and democracy. They are recognized for their contributions toward the promotion of peace and stability throughout the world in the form of humanitarian efforts, peace keeping missions and generous foreign aid.

Geography

The name Scandinavian is derived from Scania,[1][2][3][4] a region at the southernmost extremity of the peninsula.

Geographically, the Scandinavian Peninsula includes what is today mainland Sweden and mainland Norway. A small part of northwestern Finland is sometimes also considered part of the peninsula. In physiography, Denmark is considered part of the North European Plain, rather than the geologically distinct Scandinavian Peninsula mainly occupied by Norway and Sweden. However, Denmark has historically included the region of Scania on the Scandinavian Peninsula.

The Scandinavian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in Europe. It is approximately 1,850 kilometers (1,150 miles) long and between approximately 370â805 km (230-500 mi) wide. About one quarter of the peninsula lies north of the Arctic Circle, with the northernmost point at Cape Nordkyn.

The peninsula is bordered by several bodies of water including:

- the Baltic Sea (including the Gulf of Bothnia) to the east, with the autonomous Ă land islands between Sweden and Finland, and Gotland.

- the North Sea (including the Kattegat and Skagerrak) to the west and southwest

- the Norwegian Sea to the west

- the Barents Sea to the north

The Scandinavian mountain range, which runs through the peninsula, generally defines the borders between Norway, Sweden and Finland in the north, and continues into the central parts of southern Norway. The western sides of the mountains drop precipitously into the North Sea and Norwegian Sea, forming the famous fjords of Norway, while to the northeast they gradually curve towards Finland.

GaldhĂžpiggen is the highest mountain on the Scandinavian Peninsula, at 2,469 m (8,100 ft) above sea level. Glittertind, also known as Glittertinden, is the second highest mountain in the range, at 2,465 m above sea level, including the glacier at its peak (without the glacier, it is 2452 m). Both mountains are located within the municipality of Lom, in the Jotunheimen mountain area. Glittertind had earlier been a challenger for the title as the highest mountain in Norway, as measurements including the glacier was slightly higher than GaldhĂžpiggen. The glacier has, however, shrunk in recent years, and the dispute has been settled in GaldhĂžpiggen's favor. [5] These mountains also house the largest glacier on mainland Europe, Jostedalsbreen.

The climate across the peninsula varies from tundra (Köppen: ET) and subarctic (Dfc) in the north, with cool marine west coast climate (Cfc) in northwestern coastal areas reaching just north of Lofoten, to humid continental (Dfb) in the central portion, and to marine west coast (Cfb) in the south and southwest.[6]

The region is rich in timber, iron and copper with the best farmland in southern Sweden. Large petroleum and natural gas deposits have been found off Norway's coast in the North Sea and the Atlantic Ocean.

Geology

The Scandinavian Peninsula occupies part of the Baltic Shield, a stable and large crust segment formed of very old, crystalline metamorphic rocks. Most of the soil covering this substrate was scraped by glaciers during continental glaciation, especially in the northern part, where the shield is nearest the surface. As a consequence of this scouring, elevation, and climate, only a very small percentage of land is arable (3 percent in Norway).[7]

Although the Baltic Shield is largely stable and resistant to the influences of other neighboring tectonic formations, the weight of nearly four kilometers of ice sheet caused the terrain to sink. When the ice sheet disappeared, the shield rose again, a tendency that continues to this day at a rate of about 1 meter per century (Ostergren 2004). Conversely, the south part has tended to sink down to compensate, causing the flooding of the Low Countries and Denmark.

Extremely heavy, thick glaciers formed during the last ice age, deepening river valleys, which were invaded by the sea when the ice melted. The glaciers ran off the mountains and scoured troughs into Norwayâs coastline with depths that reached well below sea level. When the glaciers melted, the seawater rushed into these deep troughs to form the famous fjords which line the peninsula's west side, along Norwayâs coast. In the south the glaciers deposited many sedimental deposits, configuring a very chaotic landscape. Many of these fjords are well over 2,000 feet (610 meters) deep. The deepest fjord on Norwayâs coast, known as Sogn Fjord, lies in southwest Norway and is 4,291 feet (1,308 m) deep.

Glaciers also carved the mountains in Norway and northernmost Sweden. South of this mountainous region, however, Sweden consists mostly of flat, heavily forested land dotted with lakes. Lake VĂ€nern and Lake VĂ€ttern, the largest of the countryâs lakes, do not freeze completely during the winter months and can be seen clearly at the bottom of the peninsula. Lake VĂ€ttern, the smaller of the two lakes, was connected to the Baltic Sea during the last ice age. After the ice melted, a tremendous weight was lifted off of the peninsula, and the landmass rose up to separate the lake from the Baltic Sea. To the northeast of the peninsula lies Finland with more than 55,000 lakes, most of which were also created by glacial deposits.

The crystalline substrate and absence of soil exposes mineral deposits of metals, such as iron, copper, nickel, zinc, silver and gold.

People

The first recorded human presence in the southern area of the peninsula and Denmark dates from 12,000 years ago (Tilley 2003, 9). As the ice sheets from the glaciation retreated, the climate allowed a tundra biome that attracted reindeer hunters. The climate warmed gradually, favoring the growth of perennial trees first, and then deciduous forest which brought animals such as the aurochs. Groups of hunters-fishers-gatherers began to inhabit the area from the Mesolithic (8200 B.C.E.), until the advent of agriculture in the Neolithic (3200 B.C.E.).

The northern and central part of the peninsula is partially inhabited by the Sami people, often referred to as "Lapps" or "Laplanders." In the earliest recorded periods they occupied the arctic and subarctic regions as well as the central part of the peninsula as far south as Dalarna, Sweden. They speak the Sami language, a non-Indo-European language of the Finno-Ugric family, which is related to Finnish and Estonian.

The other inhabitants of the peninsula, according to ninth century records, were the Norwegians on the west coast of Norway, the Danes in what is now southern and western Sweden and southeastern Norway, the Svear in the region around MĂ€laren as well as a large portion of the present day eastern seacoast of Sweden and the Geats in VĂ€stergötland and Ăstergötland. These peoples spoke closely related dialects of an Indo-European language, Old Norse. Although political boundaries have shifted, these peoples still are the dominant populations in the peninsula in the early twenty-first century (Sawyer 1993).

Much of the present-day population of the peninsula is concentrated in its southern section; Stockholm and Gothenburg, both in Sweden, and Oslo in Norway are the largest cities.[8]

Political development

Although the Nordic countries look back on more than 1,000 years of history as distinct political entities, the international boundaries of the region came late and emerged gradually. It was not until the middle of the seventeenth century that Sweden secured an outlet on the Kattegat and control of the south Baltic coast. The Swedish and Norwegian boundaries were finally agreed to and marked out in 1751. The Finnish and Norwegian border on the peninsula was established after extensive negotiation in 1809, and the common Norwegian-Russian districts were not partitioned until 1826. Even then the borders were still fluid, with Finland gaining access to the Barents Sea in 1920, but ceding this territory to Russia in 1944.[9]

Denmark, Sweden and Russia dominated political relations within the Scandinavian Peninsula for centuries, with Iceland, Finland and Norway only gaining full independence in the twentieth century.

Notes

- â Haugen, Einar Ingvald. 1976. The Scandinavian languages: an introduction to their history. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674790025

- â Helle, Knut. 2003. The Cambridge history of Scandinavia. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521472997. p. XXII. "The name Scandinavia was used by classical authors in the first centuries of the Christian era to identify SkĂ„ne and the mainland further north which they believed to be an island."

- â Olwig, Kenneth R. "Introduction: The Nature of Cultural Heritage, and the Culture of Natural HeritageâNorthern Perspectives on a Contested Patrimony." International Journal of Heritage Studies, Vol. 11, No. 1, March 2005, p. 3: "The very name 'Scandinavia' is of cultural origin, since it derives from the Scanians or Scandians (the Latinised spelling of SkĂ„ninger), a people who long ago lent their name to all of Scandinavia, perhaps because they lived centrally, at the southern tip of the peninsula."

- â ĂstergĂ„rd, Uffe (1997). "The Geopolitics of Nordic Identity â From Composite States to Nation States." The Cultural Construction of Norden. Ăystein SĂžrensen and Bo StrĂ„th (eds.), Oslo: Scandinavian University Press 1997, 25-71.

- â Etojm.com. GLITTERTIND - 2464 METER Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- â Troy M. Kimmel, Jr. Köppens classification University of Texas. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- â Joseph J. Hobbs and Christopher L. Salter. 2005. Essentials Of World Regional Geography. 108. Thomson Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0534466001

- â Information Please. Scandinavia Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- â Axel Christian Zetlitz SĂžmme, 1961, The geography of Norden: Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden. London: Heinemann. OCLC 25445789

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ostergren, Robert C. and John G. Rice. 2004. The Europeans. Guilford Press. ISBN 0898622727

- Sawyer, Birgit, and Peter Sawyer. 1993. Medieval Scandinavia: from conversion to Reformation, circa 800-1500. The Nordic series, 17. Minneapolis, Minn: Univ. of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0816617384

- Tilley, Christopher Y. 2003. Ethnography of the Neolithic: Early Prehistoric Societies in Southern Scandinavia, p. 9, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521568218

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.