Pontifex Maximus

The Pontifex Maximus (which literally means "Greatest Pontiff") was the high priest of the Ancient Roman College of Pontiffs. This was the most important position in the ancient Roman religion, open only to patricians until 254 B.C.E., when a plebeian first occupied this post. A distinctly religious office under the early Roman Republic, it gradually became politicized until, beginning with Emperor Augustus, it was subsumed into the Imperial office. Its last use with reference to the emperors is found in inscriptions of Gratian, Emperor from 375 to 383 C.E., who, however, then decided to omit the words "pontifex maximus" from his title.

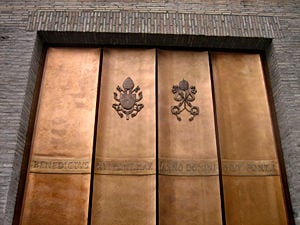

The title of "Pontifex Maximus," dating back to the times of the Roman Republic, was eventually adopted by the leader of the Roman Catholic Church. The terms pontifex maximus and summus pontifex were for centuries used by the Bishop of Rome also known as the pope. After Christ himself, the pope is considered to be the "high priest" (the veritable meaning of summus pontifex and "pontifex maximus"). However, this term is not officially included in his titles, but it is used in practice in the headings of his encyclicals and other papal documents.

Etymology

According to the usual interpretation, the term pontifex literally means "bridge-builder" (pons + facere); "maximus" literally means "greatest." This was perhaps originally meant in a literal sense: the position of bridge-builder was indeed an important one in Rome, where the major bridges were over the Tiber, the sacred river (and a deity): only prestigious authorities with sacral functions could be allowed to "disturb" it with mechanical additions. However, it was always understood in its symbolic sense as well: the pontifices were the ones who smoothed the bridge between gods and men (Van Haeperen).

An alternative view is that pontifex means "preparer of the road," derived from the Etruscan word pont, meaning "road".[1] A minority opinion is that the word is a corruption of a similar-sounding but etymologically unrelated Etruscan word for priest.

The Pagan Pontifices

Origins during the Regal Period

The Collegium Pontificum (College of Pontiffs) was the most important priesthood of ancient Rome. The foundation of this sacred college is attributed to the second king of Rome, Numa Pompilius. It is safe to say that the collegium was tasked to act as advisers of the rex (king) in all matters of religion. The collegium was headed by the pontifex maximus and all the pontifices held their office for life. Prior to its institution, all religious and administrative functions and powers were naturally exercised by the king. Very little is known about this period of Roman history regarding the pontiffs as the main historical sources are lost and some of the events from this period are regarded as semi-legendary or mythical. Most of the records of ancient Rome were destroyed when it was sacked by the Gauls in 390 B.C.E. Accounts from this early period come from excerpts of writings made during the Republican Period.

Development during the Roman Republic

In the Roman Republic, the Pontifex Maximus was the highest office in the polytheistic Roman religion, which was very much a state cult. He was the most important of the Pontifices (plural of Pontifex), in the main sacred college (Collegium Pontificum) which he directed. According to Livy, after the overthrow of the monarchy, the Romans also created the priesthood of the Rex Sacrorum or 'king of rites' or 'king of the sacred rites' to perform the religious duties and rituals and sacrifices previously done by the king. He was, however, explicitly prohibited from assuming any political office or sit in the Senate as a precaution to prevent the holder from becoming a tyrant. The Rex Sacrorum was further subordinated by the founders of the Roman Republic under the Pontifex Maximus as a further guard against tyranny.[2] Other members of this priesthood included the Flamines (each devoted to a major deity), and the Vestales. During the early Republic, the Pontifex Maximus selected the members to hold these posts. However, there were many other religious officials, including the Augures and Haruspices (two originally Etruscan types of reading of the will of the gods: from the flight and conduct of birds viz. the entrails of sacrificial animals), Fetiales and many other colleges and individual offices.

The official residence of the Pontifex Maximus was the Domus Publica which stood between the House of the Vestal Virgins and the Via Sacra, close to the Regia, in the Roman Forum. His religious duties were carried out from the Regia or 'house of the king'.

Unless the pontifex maximus was also a magistrate at the same time, he was not allowed to wear the toga praetexta (i.e. toga with the purple border). However, he could be recognized by the iron knife (secespita)[1] or the patera[3] and the distinctive robes or toga with part of the mantle covering the head.

The Pontifex was not simply a priest. He had both political and religious authority. It is not clear which of the two came first or had the most importance. In practice, particularly during the late Republic, the office of Pontifex Maximus was generally held by a member of a politically prominent family. It was a coveted position mainly for the great prestige it confers on the holder; Julius Caesar became pontifex in 73 B.C.E. and pontifex maximus in 63 B.C.E. Being Pontifex Maximus was not a full-time job and did not preclude the office-holder from holding a secular magistracy or serving in the military.

The most recent general study of the pontifical college (Van Haeperen 2002), omits the earliest periods of Roman history, as too little is known. The major Roman source, Varro's book on the pontiffs, is lost: only a little of it survives in Aulus Gellius and Nonius Marcellus. More information is to be found in remarks by Cicero, Livy, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Valerius Maximus, in Plutarch's vita of Numa Pompilius, Festus' summaries of Verrius Flaccus, and in later writers. Some of these sources present an extensive list of everyday actions that were taboo for the Pontifex Maximus; it seems difficult to reconcile these lists with evidence that many Pontifices Maximi were prominent members of society who lived normal, non-restricted lives.

Election and number of pontifices

The number of Pontifices, (s)elected by co-optatio (i.e the remaining members nominate their new colleague) for life, was originally five, including the pontifex maximus.[4][1] The pontifices, moreover, can only come from the old nobility, the patricians. However, in 300 B.C.E./299 B.C.E. the lex Ogulnia opened the office and admitted the plebs (plebeians) to run for the charge, so that part of the prestige of the title was lost. However, it was only in 254 B.C.E. that Tiberius Coruncanius became the first plebian Pontifex Maximus.[5] The lex Ogulnia also increased the number of pontiffs to nine (the pontifex maximus included). In 104 B.C.E., the lex Domitia prescribed that the election would henceforward be voted by the comitia tributa (an assembly of the people divided into voting districts); by the same law, only 17 of the 35 tribes of the city could vote. This law was abolished in 81 B.C.E. by Sulla in lex Cornelia de Sacerdotiis, which restored to the great priestly colleges their full right of co-optatio (Liv. Epit. 89; Pseudo-Ascon. in Divinat. p102, ed. Orelli; Dion Cass. xxxvii.37). Also under Sulla, the number of pontifices was increased to 15, the pontifex maximus included. In 63 B.C.E., when Julius Caesar was Pontifex Maximus, the law of Sulla was abolished and a modified form of the lex Domitia was reinstated providing for election by comitia tributa once again but Marcus Antonius later restored the right of co-optatio to the college (Dion Cass. xliv.53). Under Julius Caesar, the number of pontifices was also increased to 16, the pontifex maximus included. The number of pontifices varied during the empire but is believed to have been regular at fifteen.[4]

Extraordinary appointment of dictators

The office came into its own with the abolition of the monarchy, when most sacral powers previously vested in the King were transferred either to the Pontifex Maximus or to the Rex Sacrorum, though traditionally a (non-political) dictator was formally mandated by the Senate for one day, to perform a specific rite.

According to Livy in his "History of Rome," an ancient instruction written in archaic letters commands: "Let him who is the Praetor Maximus fasten a nail on the Ides of September." This notice was fastened up on the right side of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, next to the chapel of Minerva. This nail is said to have marked the number of the year. It was in accordance with this direction that the consul Horatius dedicated the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus in the year following the expulsion of the kings; from the Consuls the ceremony of fastening the nails passed to the Dictators, because they possessed greater authority. As the custom had been subsequently dropped, it was felt to be of sufficient importance to require the appointment of a Dictator. L. Manlius was accordingly nominated but his appointment was due to political rather than religious reasons. He was eager to command in the war with the Hernici. He caused a very angry feeling among the men liable to serve by the inconsiderate way in which he conducted the enrolment. At last, in consequence of the unanimous resistance offered by the tribunes of the plebs, he gave way, either voluntarily or through compulsion, and laid down his Dictatorship. After that point, the rite was performed by the Rex Sacrorum.[6]

Duties

The main duty of the Pontifices was to maintain 'pax deorum' or 'peace of the gods'.[7][8][9]

The immense authority of the sacred college of pontiffs was centered on the Pontifex Maximus, the other pontifices forming his consilium or advising body. His functions were partly sacrificial or ritualistic, but these were the least important. His real power lay in the administration of jus divinum or divine law;[10] the information collected by the pontifices related to the Roman religious tradition was bound in a corpus which summarized dogma and other concepts. The chief departments of jus divinum may be described as follows:

- The regulation of all expiatory ceremonials needed as a result of pestilence, lightning, etc.

- The consecration of all temples and other sacred places and objects dedicated to the gods by the state through its magistracies.

- The regulation of the calendar; both astronomically and in detailed application to the public life of the state.

- The administration of the law relating to burials and burying-places, and the worship of the Manes or dead ancestors.

- The superintendence of all marriages by conferratio, i.e. originally of all legal patrician marriages.

- The administration of the law of adoption and of testamentary succession.

The pontifices had many relevant and prestigious functions such as being in charge of caring for the state archives, the keeping the official minutes of elected magistrates and list of magistrates, and they kept the records of their own decisions (commentarii) and of the chief events of each year, the so-called "public diaries," the Annales maximi.[11]

The pontifex maximus is also subject to several taboos. Among them is the prohibition from leaving Italy. However, Plutarch described Publius Cornelius Scipio Nasica Serapio (141-132 B.C.E.) as the first to leave Italy and thus break the sacred taboo after being forced by the Senate to leave Italy. Publius Licinius Crassus Dives Mucianus (132 - 130 B.C.E.) was the first to leave Italy voluntarily. Afterwards, it became common and no longer against the law for the pontifex maximus to leave Italy. Among the most notable of which was Julius Caesar (63-44 B.C.E.).

The Pontifices were in charge of the Roman calendar and determined when intercalary days needed to be added to sync the calendar to the seasons. Since the Pontifices were often politicians, and because a Roman magistrate's term of office corresponded with a calendar year, this power was prone to abuse: a Pontifex could lengthen a year in which he or one of his political allies was in office, or refuse to lengthen one in which his opponents were in power. Under his authority as Pontifex Maximus, Julius Caesar introduced the calendar reform that created the Julian calendar, with a fault under a day per century, easily corrected by a modification of the rules for bisextile days (only added in a leap-year) to produce our present Gregorian calendar.

Under the Roman Empire

After Caesar's assassination in 44 B.C.E., his ally Marcus Aemilius Lepidus was selected as Pontifex Maximus. Though Lepidus eventually fell out of political favor and was sent into exile as Augustus consolidated power, he retained the priestly office until his death in 13 B.C.E., at which point Augustus was selected to succeed him and given the right to appoint other pontifices. Thus, from the time of Augustus, the election of pontifices ended and membership into the sacred college was deemed a sign of imperial favour.[1] With this attribution, the new office of Emperor was given a religious dignity and the responsibility for the entire Roman state cult. Most authors contend that the power of naming the Pontifices was not really used as an instrumentum regni, an enforcing power.

From this point on, Pontifex Maximus was one of the many titles of the Emperor, slowly losing its specific and historical powers and becoming simply a referent for the sacral aspect of imperial duties and powers. During the Imperial period, a promagister (vice-master) performed the duties of the pontifex maximus in lieu of the emperors whenever they were absent (Van Haeperen). In post-Severan times (post 235 C.E.), the small number of pagan senators interested in becoming pontiffs led to a change in the pattern of office holding. In Republican and Imperial times no more than one family member of a gens was member of the College of Pontiffs, nor did one person hold more than one priesthood in this collegium. Obviously these rules where loosened in the later part of the third century C.E. In periods of joint rule, two pontifices maximi could serve together, as Pupienus and Balbinus did in 238âa situation unthinkable in Republican times. In the crisis of the Third Century, usurpers did not hesitate to claim for themselves the role not only of Emperor but of Pontifex Maximus as well. Even the early Christian Emperors continued to use it; it was only relinquished by Gratian, possibly in 376 C.E. at the time of his visit to Rome,[12][13] or more probably in 383 C.E. when a delegation of pagan senators implored him to restore the Altar of Victory in the Senate House.[14]

Catholic use of the title

In Catholic circles, when Tertullian, a Montanist, furiously applied the term to Pope Callixtus I, with whom he was at odds, c. 220, over Callixtus's relaxation of the Church's penitential discipline, allowing repentant adulterers and fornicators back into the Church, under his Petrine authority to "bind and loosen," it was in bitter irony:

- "In opposition to this [modesty], could I not have acted the dissembler? I hear that there has even been an edict sent forth, and a peremptory one too. The 'Pontifex Maximus,' that is the 'bishop of bishops,' issues an edict: 'I remit, to such as have discharged [the requirements of] repentance, the sins both of adultery and of fornication.' O edict, on which cannot be inscribed, 'Good deed!' ⦠Far, far from Christ's betrothed be such a proclamation!" (Tertullian, On Modesty ch. 1)

It is not clear if the word Pontifex was commonly used by early 3rd-century Christianity, as it was later, to denote a bishop. Tertullian's usage is unusual in that most of the technical terms of Roman paganism were avoided in the vocabulary of Christian Latin in favour of neologisms or Greek words.

The last traces of emperors being at the same time chief pontiffs are found in inscriptions of Valentinian, Valens, and Gratianus (Orelli, Inscript. n1117, 1118). From the time of Theodosius I (379â395), the emperors no longer appear in the dignity of pontiff; but the title was later applied to the Christian bishop of Rome.[15] In 382, the Emperor Gratian, at the urging of St. Ambrose, removed the Altar of Victory from the Forum, withdrew the state subsidies that funded many pagan activities and formally renounced the title of Pontifex Maximus.[16] It is said that Pope Damasus I was the first Bishop of Rome to assume the title,[17] Other sources say that the use of such titles by bishops, including the Bishop of Rome, came later.[18] The title pontifex continued to be a title for both the bishop of Rome and other bishops. In Emperor Theodosius's edict De fide catholica[19] of February 27, 380, enacted in Thessalonica and published in Constantinople for the whole empire, by which he established Catholic Christianity as the official religion of the empire, he referred to Damasus as a pontifex,[20]while calling Peter an episcopus : "... the profession of that religion which was delivered to the Romans by the divine Apostle Peter, as it has been preserved by faithful tradition and which is now professed by the Pontiff Damasus and by Peter, Bishop of Alexandria ... We authorize the followers of this law to assume the title Catholic Christians ..." Some see in this an implied significant differentiation, but the title pontifex maximus is not used in the text; pontifex is used instead: "... quamque pontificem damasum sequi claret et petrum alexandriae episcopum..." (Theodosian Code XVI.1.2; and Sozomen, "Ecclesiastical History," VII, iv. [21]).

Without quoting its source, the Encyclopædia Britannica attributes to Pope Leo I (440-461 C.E.) the assumption of the title Pontifex Maximus.[22] This was a time when the declining Roman Empire was in transition from pagan to Christian, and Constantinople would begin to assert itself to pre-eminence, historically leading to conflict with the Bishops of Rome. Soon there would be the final collapse of the Roman Empire with the invasions of the Huns and the Vandals.

While the title Pontifex Maximus has for some centuries been used in inscriptions referring to the Popes, it has never been included in the official list of papal titles published in the Annuario Pontificio, which instead includes "Supreme Pontiff of the whole Church" (in Latin, Summus Pontifex Ecclesiae Universalis) as the fourth official title, the first being "Bishop of Rome."

The terms pontifex maximus and summus pontifex were for centuries used not only of the Bishop of Rome but of other bishops also. Hilary of Arles (d. 449) is styled "summus pontifex" by Eucherius of Lyons (P. L., L, 773), and Lanfranc is termed "primas et pontifex summus" by his biographer, Milo Crispin (P. L., CL, 10); they were doubtless originally employed with reference to the Jewish high-priest, whose place the Christian bishops were regarded as holding each in his own diocese (I Clement 40), but from the eleventh century they appear to be applied only to the Pope.[23]

The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church says that it was in the fifteenth century that "Pontifex Maximus" became a regular title of honour for Popes.[24]

After Christ himself,[25] the pope is the "high priest" (the veritable meaning of summus pontifex and "pontifex maximus")[26] of the Catholic religion.

- The title Pontifex Maximus was briefly used, from 1902 to 1906, by the head of the Philippine Independent Church.

- The title Pontifex Maximus has also been in continual use by the high priest of the White Separatist religion, Creativity, since its inception in 1973 by Ben Klassen.

Tradition of sovereign as high priest

The practice of religious and secular authority united in the sovereign has a long history. In ancient Athens, the Archon basileus was the principal religious dignitary of the state; according to legend, and as indicated in his title of "Basileus" (meaning "king"), he was supposed to inherit the religious functions of the king of Athens in earlier times.[27]

Eastern traditions, from the ancient Egyptian to the Japanese, carried the concept even further, according their sovereigns demigod status.

With the adoption of Christianity, the Roman emperors took it on themselves to issue decrees on matters regarding the Christian Church. Unlike the Pontifex Maximus, they did not themselves function as priests, but they acted practically as head of the official religion, a tradition that continued with the Byzantine emperors. In line with the theory of Moscow as the Third Rome, the Russian Tsars exercised supreme authority over the Russian Orthodox Church.

With the English Reformation, the sovereign of England became Supreme Governor of the Church of England and insisted on being recognized as such. Only at a later stage was effective separation of church and state introduced. Much the same occurred in other countries affected by the Protestant Reformation.

Even in countries where there was no formal break with the Holy See, various sovereigns assumed similar authority. An example is Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor.

A secular equivalent of the ruler as head of religion is that of the philosopher king, based on a notion in Plato's Republic. Several rulers have been pictured as, at least to some extent, embodying that concept.

Popular culture

In the Protestant Evangelical fiction series Left Behind, Cardinal Peter Mathews is named Pontifex Maximus of Enigma Babylon One World Faith, established by Global Community Supreme Potentate and Antichrist Nicolae Carpathia.

In C. S. Lewis's Christian novel The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, Aslan refers to himself as "the great Bridge-Builder," the literal English translation of Pontifex Maximus.

The White separatist group the (former) World Church of the Creator referred to the founder of Creativity, Ben Klassen, and leader Matt Hale as Pontifex Maximus. Hale was also commonly referred to as "the Great Promoter" by church membership, a symbolic rather than literal English translation of Pontifex Maximus.

Notes

- â 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Pontifex Maximus Livius.org article by Jona Lendering. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- â Roman Public Religion Roman Civilization, bates.edu

- â Panel Reliefs of Marcus Aurelius and Roman Imperial Iconography State University of New York, College at Oneonta. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- â 4.0 4.1 Pontifex Maximus LacusCurtius. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- â Titus Livius Ex Libro XVIII Periochae, from livius.org Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- â Livius, Titus. "History of Rome" (HTML). Ancient History Sourcebook: Accounts of Roman State Religion, c. 200 B.C.E.- 250C.E.. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- â The Roman Persecution of Christians By Neil Manzullo February 8th, 2000 Persuasive Writing, Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- â Pax Deorum everything2.com. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- â "Roman Mythology," Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006 encarta.msn.com © 1997-2006 Microsoft Corporation. All Rights Reserved. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- â jus divinum, Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- â Pontifex, Encyclopedia Britannica, 1911 Ed. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- â "Gratian." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved February 15, 2009. Gratian.

- â Van Haeperen

- â A. Cameron, "Gratian's Repudiation of the Pontifical Robe" The Journal of Roman Studies 58 (1968): 96-102 - the confusion in dates arises from Zosimus, who writes that it was repudiated at Gratian's accession, impossible from epigraphic and literary references

- â Pontifex Maximus, Columbia Encyclopedia Sixth Edition. 2001-05., bartleby.com Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- â Emperor Gratian Roman Emperors Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- â Pontifex Maximus Mark Bonocore Retrieved February 15, 2009. This seems to be based on the Theodosian Code, XVI.i.2, which refers to Pope Damasus merely as a pontifex, not as the pontifex maximus. The Christian Apostolic Succession, The Role and Function of Thelemic Clergy in Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica, Retrieved February 15, 2009. states that Damasus refers to himself as Pontifex Maximus in a petition to the Emperor for judicial immunity, but gives no source for this statement.

- â "Christian emperors relinquished the title Pontifex Maximus as too closely tied with the pagan past (Schimmelpfennig, 34). Bishops, including the bishop of Rome, sometime thereafter, began to make use of pontifex as a title for themselves" John D. Beetham, Papal Prerogatives and Titles, 5 September 2001 (emphasis added).

- â De fide catholica, Retrieved February 23, 2009.

- â Unlike episcopus (from Greek á¼ÏίÏκοÏοÏ), the word used for the bishop from the Greek-speaking East, pontifex is a word of purely Latin derivation. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- â Emperor Theodosius I. "IMPERATORIS THEODOSIANI CODEX Liber Decimus Sextus" (web). ancientrome.ru. Retrieved 2006-12-04. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- â Papacy Encyclopædia Britannica. 2006. Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service.

- â Catholic Encyclopedia: Pope, Titles Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- â Pontifex Maximus, in Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford University Press 2005 ISBN 9780192802903

- â Catechism of the Catholic Church, 662, 1137, 1544 Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- â The Roman title of "Pontifex Maximus" was rendered in Greek inscriptions and literature as "á¼ÏÏιεÏεÏÏ" (Polybius 23.1.2 and 32.22.5; Corpus Inscriptionum Atticarum 3.43, 3.428 und 3.458) or by a more literal translation and order of words, "á¼ÏÏιεÏÎµá½ºÏ Î¼ÎγιÏÏοÏ" (Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum 2.2696 and 3.346; Plutarch Numa 9.4). The first of these terms is used in the New Testament and in the Septuagint text of the Old Testament to refer to the Jewish high priest.

- â Myth Notes; 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica: Archon; Encyclopaedia Britannica Online: Archon Retrieved February 15, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bury, John Bagnell. A History of the Roman Empire From its Foundation to the Death of Marcus Aurelius. NY: Russell & Russell, 1965. (original 1913)

- Crook, J. A. Law and Life of Rome, 90 B.C.E.âAD 212. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1967. ISBN 0801492734.

- Dixon, Suzanne. The Roman Family. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1992. ISBN 080184200X

- Dudley, Donald R. The Civilization of Rome. NY: New American Library, 2nd ed., 1985. ISBN 0452010160.

- Jones, A. H. M. The Later Roman Empire, 284â602. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986. ISBN 0801832853.

- Lintott, Andrew. Imperium Romanum: Politics and Administration. London & NY: Routrledge, 1993. ISBN 0415093759.

- Macmullen, Ramsay. Roman Social Relations, 50 B.C.E. to AD 284. New Haven, CT: Yale Univesity Press, 1981. ISBN 0300027028.

- Rostovtzeff, Michael. The Social and Economic History of the Roman Empire. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2nd ed., 1957.

- Syme, Ronald. The Roman Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002. (original 1939). ISBN 0192803204.

- Van Haeperen, Françoise. Le collège pontifical (3ème s. a. C. - 4ème s. p. C.) in series Ãtudes de Philologie, d'Archéologie et d'Histoire Anciennes, no. 39. Brussels: Brepols, 2002. ISBN 9074461492

External links

All links retrieved November 24, 2022.

- "Pontifex" from William Smith's Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.