| Part of the series on Eastern Christianity | |

| |

|

History | |

|

Traditions | |

|

Liturgy and Worship | |

|

Theology | |

Monophysitism (from the Greek monos meaning "one" and physis meaning "nature") is the christological position that Christ has only one nature, in which his divinity and humanity are united. The opposing Chalcedonian ("orthodox") position holds that Christ has two natures, one divine and one human. Monophysitism also refers to the movement centered on this concept, around which a major controversy evolved during the fifth through sixth centuries C.E.

Monophysitism grew to prominence in the Eastern Roman empire, particularly in Syria, the Levant, Egypt, and Anatolia, while western church, under the discipline of the papacy, denounced the doctrine as heresy. Monophysitism was rejected at the Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon in 451, and repressed as a result. However, it continued to have many adherents. The controversy reemerged in a major way in the late fifth century, in the form of the Acacian schism, when Patriarch Acacius of Constantinople and Emperor Zeno sought to reconcile Monophysite and Chalcedonian Christians by means of the Henotikon, a document which sought to avoid the debate over the question of Christ's "natures."

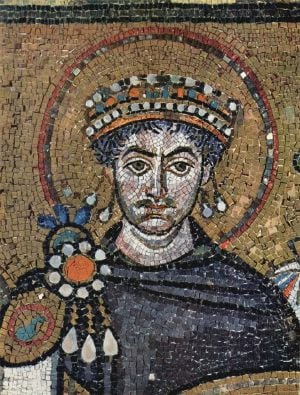

Monophysitism received new life again during the reign of Justinian I, who sought to heal the breach in the eastern churches by achieving a universal denunciation of the so-called Three Chaptersâideas particularly offensive to the Monophysitesâby holding the Second Council of Chalcedon, to which Pope Vigilius was successfully pressured to submit.

Today's miaphysite churches of the Oriental Orthodox tradition, such as the Coptic Orthodox Church and others, are related historically to Monophysitism and honor saints condemned in Catholic tradition as heretics, but are generally accepted as authentically Christian by other communions.

History

Although there are many permutations of the idea, two major doctrines are specifically associated with Monophysitism: Eutychianism, which held that the human and divine natures of Christ were fused into one new single (mono) nature, and Apollinarianism, which held that, while Christ possessed a normal human body and emotions, the Divine Logos had essentially taken the place of his nous, or mind. It is the Eutychian form of Monophysitism which became the cause of the major controversies referred to below.

Background

The doctrine of Monophysitism can be seen as evolving in reaction to the "diaphysite" theory of Bishop Nestorius of Constantinople in the early fifth century. Nestorius attempted to explain rationally the doctrine of the Incarnation, which taught that God the Son had dwelt among men in the person of Jesus of Nazareth. Nestorius held that the human and divine essences of Christ were distinct, so that the man Jesus and the divine Logos, were in effect two "persons" (Greek: hypostasis) in a similar sense of the Trinity being three "persons." (The Greek word hypostasis, translated into Latin as "persona," does not carry the same sense of distinction as the Latin, a factor that has contributed to the many theological misunderstandings between eastern and western Christianity, both during this and other theological controversies.) Nestorius ran into particular trouble when he rejected the term Theotokos (God-bearer or Mother of God) as a title of the Virgin Mary, suggesting instead the title Christotokos (Mother of Christ), as more accurate.

Bishop Cyril of Alexandria led the theological criticism of Nestorius beginning 429. "I am amazed," he wrote, "that there are some who are entirely in doubt as to whether the holy Virgin should be called Theotokos or not." Pope Celestine I soon joined Cyril in condemning Nestorius. After considerable wrangling and intrigue, the Ecumenical Council of Ephesus in 431 condemned Nestorianism as heresy. Nestorius himself was deposed as bishop of Constantinople and excommunicated.

Eutychianism

In opposition to Nestorius, Cyril of Alexandria taught thatâalthough Jesus is fully God and fully manâ"There is only one physis (nature)" in Christ, and this nature is to be understood as the sense of the Incarnation of God the Son. Although this sounds very much like what was later condemned as Monophysitism, Cyril's orthodoxy was apparently beyond reproach. Eutyches (c. 380âc. 456), a presbyter and archimandrite of a monastery of 300 monks near Constantinople, emerged after Cyril's death as Nestorianism's most vehement opponent. Like Cyril, he held that Christ's divinity and humanity were perfectly united, but his vehement commitment to this principle led him to insist even more clearly that Christ had only one nature (essentially divine) rather than two.

Eutychianism became a major controversy in the eastern church, and Pope Leo I, from Rome, wrote that Eutyches' teaching was indeed an error. Eutyches found himself denounced as a heretic in November 447, during a local synod in Constantinople. Due to the great prestige that Eutyches enjoyed, Archbishop Flavian of Constantinople did not want the council to consider the matter, but he finally relented, and Eutyches was condemned as a heretic. However, Emperor Theodosius II and Patriarch Dioscorus of Alexandria did not accept this decision. Dioscorus held a new synod at Alexandria reinstating Eutyches, and the emperor called an empire-wide council, to be held in Ephesus in 449, inviting Pope Leo I, who agreed to be represented by four legates.

The Second Council of Ephesus convened on August 8, 449, with some 130 bishops in attendance. Dioscorus of Alexandria presided by command of the emperor, who denied a vote to any bishop who had voted in Eutyches' deposition two years earlier, including the archbishop Flavian himself. As a result, there was nearly unanimous support for Eutyches. The pope's representatives, notably the future Pope Hilarius, were among the few who objected. Moreover, the council went so far as to condemn and expel Archbishop Flavian of Constantinople. He soon died, according to some reports as a result of being beaten by Eutyches' supporters. Hilarius, in fear of his own life, returned to Rome by back roads, reporting that a papal letter intended for the synod had never been read.

The decisions of this council threatened schism between the East and the West, and the meeting soon became known as the "Robber Synod." However, with Eutyches restored to orthodoxy in the East, Monophysitism gained a strong foothold in many churches.

Chalcedon

The ascension of Emperor Marcian to the imperial throne brought about a reversal of the christological policy in the East. The Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon was now convened in 451, under terms less favorable to the Monophysites. It promulgated the doctrine which ultimatelyâthough not without serious challengesâstood as the settled christological formula for most of Christendom. Eutychianism was once again rejected, and the formula of "two natures without confusion, change, division, or separation" was adopted:

We confess that one and the same Christ, Lord, and only-begotten Son, is to be acknowledged in two natures without confusion, change, division, or separation. The distinction between natures was never abolished by their union, but rather the character proper to each of the two natures was preserved as they came together in one person and one hypostasis.

Although this settled matters between Constantinople and Rome on the christological issue, a new controversy arose as a result of Chalcedon's canon number 28, granting Constantinople, as "New Rome," equal ecclesiastical privileges with "old" Rome. This was unacceptable to the pope, Simplicius, who announced that he accepted the council's theological points, but rejected its findings on church discipline.

Imperial policy shifts

Although many of its bishops were ousted from their sees of Chalcedon, Monophysitism continued to be a major movement in many eastern provinces. Popular sentiment on both sides of the issue was intense, sometimes breaking out into violence over the nomination of bishops in cities that were often divided between Monophysite and Chalcedonian factions.

In 476, after Emperor Leo II's death, Flavius Basiliscus drove the new emperor, Zeno, into exile and seized the Byzantine throne. Basiliscus looked to the Monophysites for support, and he allowed the deposed Monophysite patriarchs Timotheus Ailurus of Alexandria and Peter Fullo of Antioch to return to their sees. At the same time, Basiliscus issued a religious edict which commanded that only the first three ecumenical councils were to be accepted, rejecting the Council of Chalcedon. All eastern bishops were commanded to sign the edict. The patriarch of Constantinople, Acacius, wavered; but a popular outcry led by rigidly orthodox monks moved the him to resist the emperor and to reject his overtures to the Monophysites.

When the former emperor, Zeno, regained power from Basiliscus in 477, he sent the pope an orthodox confession of faith, whereupon Simplicius congratulated him on his restoration to power. Zeno promptly voided the edicts of Basiliscus, banished Peter Fullo from Antioch, and reinstated Timotheus Salophakiolus at Alexandria. At the same time, he also allowed the Monophysite Patriarch Timotheus Ailurus to retain his office in the same city, reportedly on account of the latter's great age, but also no doubt because of the strength of the Monophysite sentiment there. In any case, Ailurus soon died. The Monophysites of Alexandria now put forward Peter Mongus, the Ailurus' archdeacon, as his successor. Urged by the pope and the orthodox parties of the east, Zeno commanded that Mongus, also known as Peter the Stammerer, be banished. Peter, however, was able to remain in Alexandria, and fear of the Monophysites again prevented the use of force.

Meanwhile, the orthodox patriarch, Timotheus Salophakiolus, risked the ire of the anti-Monophysites by placing the name of the respected deceased pro-Monophysite patriarch Dioscurus I on the diptychs, the list of honored leaders to be read at the church services. Pope Simplicius wrote to Patriarch Acacius of Constantinople on March 13, 478, urging that Salophakiolus should be commanded to reverse himself on this matter. Salophakiolus sent legates and letters to Rome to assure the pope that Dioscorus' name would be removed from the lists.

Patriarch Acacius continued to move against the Monophysistes, and at his request, Pope Simplicius condemned by name the previously mentioned "heretics," patriarchs Mongus and Fullo, as well as several others. The pope also appointed Acacius as his representative in the matter. When the Monophysites at Antioch raised a revolt in 497 against anti-Monophysite Patriarch Stephen II and killed him, Acacius himself chose and consecrated Stephen's successors, an action which the pope would resent.

Simplicius demanded that the emperor punish the murderers of the orthodox patriarch, butâever vigilant to defend Rome's prerogativesâstrongly reproved Acacius for allegedly exceeding his right in performing the consecration of Stephen III. Relations between the patriarchs of "old" Rome and "new" Rome (Constantinople) now soured considerably.

The Henotikon

After the death of Salophakiolus in Alexandria, the Monophysites again elected Peter Mongus as patriarch, while the orthodox chose Johannes Talaia. Despite Acacius' earlier opinion that Mongus was a heretic, both Acacius and the emperor were opposed to Talaia and sided with Mongus. Emperor Zeno, meanwhile, was very desirous of ending the strife between the Monphysite and Chalcedonian factions, which was causing considerable difficulty. The document known as the Henotikon, approved by Zeno in 481, was an attempt to achieve such a conciliation.

The Henotikon begins by upholding the faith defined at the first three ecumenical councils at Nicaea, Constantinople, and Ephesus. Nestorius and Eutyches are both condemned, and the anathemas against them by Cyril of Alexandria are approved. Christ is defined as both God and man, but "one, not two." Whether this "one" refers to his "person" or "nature" is carefully not said. Only one of the Trinity (the Son) was incarnate in Jesus. Whoever thinks otherwise is anathematized, especially Nestorius, Eutyches, and all their followers.

The Henotikon intentionally avoided the standard Catholic formula ("one Christ in two natures") and pointedly named only the first three ecumenical councils with honor. It was thus easily seen as a repudiation of the Council of Chalcedon.[1]

The more insistent of the Monophysites were not content with this formula and separated themselves from Patriarch Peter Mongus of Alexandria, forming the sect called the Acephali ("without a head"âwith no patriarch). Nor were the Catholics satisfied with a document that avoided declaring the faith of Chalcedon. The emperor, however, succeeded in persuading Patriarch Acacius to accept the Henotikon, a fact that is remarkable, since Acacius had stood out firmly for the Chalcedonian faith under Basiliscus. However, the strained relations between Rome and Constantinople over the question of the latter's disputed status was also a factor.

The Henotikon was addressed in the first place to the Egyptians, centering on Alexandria, but was soon applied to the whole empire. Both Catholic and strict Monophysite bishops were deposed if they did not assent to it, and their sees were given to churchmen who agreed to the compromise.

The Acacian schism

However, the emperor had not anticipated the effect of Rome. From all parts of the eastern church, bishops sent complaints to Pope Felix III (483-92) entreating him to stand out for the Council of Chalcedon. Felix's first known official act was to repudiate the Henotikon and address a letter of remonstrance to Acacius. In 484, Felix excommunicated Peter Mongus, greatly exacerbating hard feelings between East and West. Legates sent from Rome to Constantinople, however, were heard to utter the name of Peter in the readings of the sacred diptychs there. When this was made known at Rome, Felix convened a synod of 77 bishops in the Lateran Basilica, in which it was alleged that the legates had only pronounced Peter as orthodox under duress. Patriarch Acacius himself was now excommunicated, and the synod further demonstrated its firmness in opposition to any compromise with Monopysitism by excommunicating the supposedly mistreated papal envoys as well.

Acacius himself died in 489. Zeno died in 491, and his successor, Anastasius I (491-518), began by keeping the policy of the Henotikon, gradually becoming more sympathetic with complete Monophysitism as Catholic opposition to the Henotikon increased.

After Acacius' death, an opportunity for ending the schism arose when he was succeeded by the orthodox Patriarch Euphemius, who restored the names of the recent popes to the diptychs at Constantinople and seemed amenable to reunion. However, when Pope Gelasius I insisted on the removal of the name of the much respected Acacius from the diptychs, he overstepped, and the opportunity was lost. Gelasius' book De duabus in Christo naturis ("On the dual nature of Christ") delineated the western view and continued the papal policy of no compromise with Monophysitism.

The next pope, Anastasius II, wavered in this attitude when he offered communion to Deacon Photinus of Thessalonica, who was a supporter of the Acacian party. So adamant were the feelings in Rome against such an act that when this pope died shortly afterward, the author of his brief biography in the Liber Pontificalis would state that he was "struck dead by divine will."

Relations between East and West deteriorated under the reign of Pope Symmachus. Shortly after 506, the emperor wrote to Symmachus a letter full of invectives for daring to interfere both with imperial policy and the rights of the eastern patriarch. The pope replied with an equally firm answer, maintaining in the strongest terms the rights and Roman church as the representative of Saint Peter. In a letter of October 8, 512, addressed to the bishops of Illyria, the pope warned the clergy of that province not to hold communion with "heretics," meaning Monophysites, a direct assault on the principles of the Henotikon.

The schism ends

In 514, Emperor Anastasius was forced to negotiate with Pope Hormisdas after a pro-Chalcedon military commander, Vitalian, raised a considerable following and defeated the emperor's nephew in battle outside Constantinople. Hormisdas' formula for reunion, however, constituted complete capitulation to the Catholic view and Rome's supremacy, something that Anastasius was unwilling to accept. Delays in the negotiations resulted in Anastasius buying adequate time to put down the military threat by Vitalian. He now adopted a more overtly pro-Monophysite attitude and took sterner measures against those who opposed the Henotikon.

When Anastasius suddenly died, in 518, the situation changed dramatically. He was replaced by Justin I, a Chalcedonian Christian who soon caused a synod to be held at Constantinople, where the formula of Hormisdas was adopted, a major triumph for the papacy. Monphysitism was now placed firmly on the defensive, and a purge of Monophyiste bishops was instituted throughout the East.

Justinian and the Three Chapters

Nevertheless, Monophysitism remained a powerful movement, especially in the churches of Egypt and Syria, centered on the ancient patriarchal cities of Alexandria and Antioch. Like Zeno before him, Emperor Justinian I tried to bring his fractured empire together by reconciling the Chalcedonian and Monophysite factions. His wife Theodora was reportedly a secret Monophysite, and in 536, Justinian nominated a Monophysite, Anthimus I, as patriarch of Constantinople.

In 543-44, Justinian promoted the anathamatization of the so-called Three Chapters. These consisted of: 1) The person and allegedly Nestorian writings of Theodore of Mopsuestia 2) certain writings of Theodoret of Cyrrus which could likewise be interpreted as pro-Nestorian and 3) the letter of Ibas to Maris in Persia.

Many eastern bishops and all of the eastern patriarchs signed the document. In Western Europe, however, the procedure was considered unjustifiable and dangerous, on the grounds that, like the Henotikon it detracted from the importance of the Council of Chalcedon and tended to encourage the Monophysites.

The Second Council of Constantinople (May-June, 553) was called by Emperor Justinian to further the reconciliation process and solidify support for the anathematization of the Three Chapters. However, it was attended mostly by eastern bishops, with only six western delegates from Carthage being present. In the end, it both confirmed all the canons of Chalcedon, and condemned the Three Chapters.

Pope Vigilius, meanwhile, refused to acknowledge the imperial edict promulgating the anathematization of the Three Chapters and was thus called to Constantinople by Justinian, who had earlier retaken Italy from the Ostrogoths, in order to settle the matter there with a synod there. The pope was taken by imperial guards to a ship and carried to the eastern capital. If the story related by the Liber Pontificalis is correct, the pope left Rome on November 22, 545, and reached Constantinople about the end of 546, or early 547. Vigilius at first refused to make concessions, but wavered under pressure and finally agreed to the decisions of the Second Council of Constantinople in a formal statement of February 26, 554. He had been held captive for eight years at Constantinople before being able to start on his return to Rome in the spring of 555, although he died before arriving.

Monophysitism soon faded in the main centers of the Byzantine Empire, but continued to be widely accepted in Syria (Antioch), the Levant (Jerusalem), and Egypt (Alexandria), leading to continued tensions. Later, Monothelitism was developed as another attempt to bridge the gap between the Monophysite and the Chalcedonian positions, but it too was rejected by the followers of Chalcedonian orthodoxy, despite at times having the support of the Byzantine emperors and one of the popes, Honorius I.

Legacy

Monophysitism, aside from its theological significance, showed how significant the role of the eastern emperor had become in church affairs. Known as caesaropapism, this tendency was rightly criticized in the West, where the papacy had successfully established itself for the most part as an agent independent of the Roman state. The sad story of Pope Vigilius' unwilling sojourn and ultimate capitulation to the emperor in Constantinople dramatizes how different were the eastern and western traditions of church-state relations.

Miaphysitism, the christology of today's Oriental Orthodox churches, is often considered a variant of Monophysitism, but these churches insist that their theology as distinct from Monophysitism and have anathematized Eutyches since the seventh century. Nevertheless many of the "Monophysites" condemned as heretics in the fifth and sixth centuries are still honored as saints the "miaphysite" churches today.

Modern miaphysite churches, such as the Armenian Apostolic, Coptic Orthodox, Ethiopian Orthodox, and Syrian Orthodox churches, are now generally accepted by Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Protestant Christendom as authentically Christian in nature.

See also

- Nestorianism

- Henotikon

- Three-Chapter Controversy

- Acacius of Constantinople

- Eutyches

- Cyril of Alexandria

- Justinian I

Notes

- â The Catholic Encyclopedia]], Henoticon. Retrieved July 11, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Frend, W.H.C. The Rise of the Monophysite Movement; Chapters in the History of the Church in the Fifth and Sixth Centuries. Cambridge: University Press, 1972. ISBN 9780521081306.

- Roey, A. van, and Pauline Allen. Monophysite Texts of the Sixth Century. Peeters, 1994. ISBN 978-9068315394.

- Torrance, Iain R., Severus, and Sergius. Christology After Chalcedon: Severus of Antioch and Sergius the Monophysite. Norwich: Canterbury Press, 1988. ISBN 9780907547976.

External links

All links retrieved June 1, 2025.

- Monophysites and Monophysitism Catholic Encyclopedia.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.