Hong Xiuquan

- This is a Chinese name; the family name is Hong.

Hóng Xiùquán (洪秀全, Hóng Xiùquán, Hung Hsiu-ch'üan, January 1, 1814 – June 1, 1864) was a Chinese religious prophet and leader of the Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864), which established the short-lived "Heavenly Kingdom of Taiping" over portions of southern China and altered the course of modern Chinese history. Raised and educated as a Confucianist, Hong failed the civil service examinations four times. In 1837, during an illness, Hong had a religious vision, in which a man with a golden beard told him to purify the land of evil, and a middle-aged man instructed him on exterminating demons. In 1843, he read The Benevolent Words to Advise the World (《勸世良言》), a booklet written by the Christian Liang Fa, and interpreted his vision to mean that God and Jesus had instructed him, as the second son of God, to purify the world. He began to consider himself a Christian and to regard the Chinese culture of his day as the work of evil demons, insisting that all its symbols be destroyed.

In 1844, Hong and his follower Feng Yun-shan founded the "God Worshippers Society" (Pai Shang-ti Hui, 拜上帝會) in Guangxi. In 1851, having amassed approximately 10,000 followers, Hong proclaimed the "Heavenly Kingdom of Taiping" and began to rebel against the imperial forces. Gathering more and more followers along the way, he made his way north and took the city of Nanking, where he established his capital, T'ien-ching. Hong initiated a number of political and social reforms, including the abolition of private property, state ownership and distribution of land, a classless society, equality of men and women, the replacement of the lunar calendar with a solar calendar, prohibition of foot-binding, and laws prohibiting opium, gambling, tobacco, alcohol, polygamy, slavery, and prostitution. The reforms, however, were implemented harshly and ineffectively. Hong died in June of 1864, one month before Nanking fell to imperial forces. About twenty million civilians and soldiers are thought to have died during the Taiping Rebellion, making it the largest civil war in history.

Early Life and Education

Hóng Xiùquán was born Hong Renkun (洪仁坤), Courtesy name Huoxiu, 火秀) January 1, 1814 in Fuyuanshui Village (福源水村), Hua County (花縣 , Fa Yuen, now Huadu (花都市)), Guangdong, to a Hakka family. His parents were Hong Jingyang (洪競揚) and Wang-shi (王氏). His grandfather, Hong Guoyou (洪國游), was, like his ancestors, a farmer, who later moved to Guānlùbù Village (官祿[土布]¹村). Hong was the youngest of four children.

Hong started studying in Book Chamber Building (書房閣), a private school (私塾), at age seven. He was able to recite the Four Classics after five or six years. At around the age of 15 his parents were no longer able to afford his education, so he became a tutor to other children in his village and continued to study privately. He sat in his local preliminary examinations and came first, so in 1836, at the age of 22 in 1836, he sat the first-degree (秀才) civil service examinations in Guangzhou. He failed, although it should be remembered that most imperial examinations had a pass rate of one percent because there was such a large number of candidates.[1]. He tried again, four times, each time traveling to the provincial capital of Canton, and never succeeded.

He later took a position as an instructor (塾師) at Book Chamber Building and several schools in Lianhuatang (蓮花塘) and other villages.

Visions

In 1837, after he failed the civil service examinations for the third time, Hóng fell ill and was delirious for several days. During this time he had a psychogenic experience in which he dreamed of being carried by angels to heaven, where he met a man in black dragon cloak with a long golden beard who cut out his organs, replaced them with new ones, gave him a sword and a magic seal, and told him to purify the land of evil. He met some of his ancestors, and encountered a middle-aged man who instructed him in the extermination of demons.

Conversion to Christianity

Hong recovered and returned to his occupation as a village teacher. In 1843 he took the civil service examinations for the fourth time, and failed again. Soon afterwards, his cousin Li Ching-Fang noticed a booklet on Hong’s bookshelf, a copy of booklet The Benevolent Words to Advise the World (《勸世良言》), written by the Christian Liang Fa, which had been given to him by someone in Canton after his second attempt at the examination. Hong had looked at it briefly and then forgotten about it. Now, Hong re-read the book and suddenly realized the meaning of his vision. He realized that he had been transported to Heaven, that the old man with the golden beard was God, and the middle-aged man, Jesus. Hong began to believe that he was the second son of God, the adopted younger brother to Jesus, a new Messiah on earth with a mission to found a new kingdom. In reading the portions of the Bible contained in the Ch'üan-shih liang-yen, Hung translated the pronouns “I,” “we,” “you,” and “he” to refer to himself, as if the book had been written for him. He baptized himself, prayed, and from then on considered himself a Christian. His friends and family said that after this episode he became authoritative and solemn.

In his house, Hong burned all Confucian and Buddhist statues and books, and began to preach to his community about his visions. His earliest converts were relatives of his who had also failed their examinations and belonged to the Hakka minority, Feng Yunshan (Feng Yün-shan, 馮 雲山) and Hong Rengan. As a symbolic gesture of purging China of Confucianism, he asked for two giant swords, three-chi (about one metre) long and nine-jin (about 5.5 kg), called the "demon-slaying swords" (斬妖劍), to be forged.

The God Worshippers

The actions of Hong and his converts were considered sacrilegious and they were persecuted by Confucians. In 1844, Hong lost his job as tutor after he destroyed the tablets dedicated to Confucius at the school where he was teaching. Hong Xiuquan and Feng Yunshan fled the district and walked some 300 miles to Guangxi (Traditional Chinese: 廣西) where they founded an iconoclastic sect called the "God Worshippers Society" (Pai Shang-ti Hui, 拜上帝會).

Hong then preached to a large number of charcoal-burners on who worked on Zijin Mountain (紫金山) in Guiping District (桂平縣), who mostly belonged to the Hakka minority like Hong himself, and readily joined his sect. He preached a mix of communal utopianism, evangelism and idiosyncratic quasi-Christianity. The sect segregated men from women and encouraged all its followers to pay their assets into a communal treasury.

In 1847, Hong studied the Old Testament for four months in Hong Kong under the tutelage of Issachar Jacox Roberts, a Baptist missionary from the United States. This was the only only formal training he received in the doctrines of Christianity. His writings showed little understanding of Christian concepts such as original sin and redemption, or the ideals of humility and kindness, but stressed the wrathful God of the Old Testament, who required obedience. Hong demanded that evil practices such as opium smoking, gambling and prostitution be abolished, and promised an ultimate reward to those who followed the teachings of the Lord. After Hong asked him for aid in maintaining his sect, Roberts, who was wary of people converting to Christianity for economic reasons, refused to baptise them.

Through his contact with Western Christianity, Hong became aware that other nations existed in the world beyond China, and spoke of a world of many nations, all equal under God. He had an iconoclastic attitude towards the Chinese culture of his day, regarding it as the work of evil demons and insisting that all its symbols be destroyed.

Beginning of the Taiping Rebellion

When Hong left Roberts and returned to Guangxi, he found that Feng had accumulated a following of around 2,000 converts, and was accepted as leader of the new group. At that time, Guangxi was a dangerous area, with many bandit groups based in the mountains and pirates on the rivers. Perhaps due to these more pressing concerns, the authorities were largely tolerant of Hong and his followers. However, the instability of the region meant that the God Worshippers, with their predominately Hakka ethnicity, were inevitably drawn into conflict with other groups. There are records of numerous incidents where local villages and clans (as well as groups of pirates and bandits) came into conflict with the authorities, and responded by fleeing to join the God Worshippers. The rising tension between the sect and the authorities was probably the most important factor in Hong's eventual decision to rebel. Conditions of life in the countryside were severe, and the people resented the foreign Manchu rulers of China.

By 1850, Hong had amassed at least 10,000 followers, possibly as many 30,000. The authorities were alarmed at the growing size of the sect and ordered them to disperse. When they refused a local force was sent to attack them, but the imperial troops were routed and a deputy magistrate killed. A full-scale attack was launched by the government forces in the first month of 1851. In what came to be known as the Jintian Uprising (after the town of Jintian (now Guiping) where the sect was based) the God Worshippers emerged victorious, and beheaded the Manchu commander of the government troops.

The Heavenly Kingdom

On January 1, 1851, Hong declared the foundation of a new dynasty, the T'ai-p'ing T'ien-kuo ("Heavenly Kingdom of Transcendant Peace") and assumed the title of T'ien Wang, or Heavenly King. The speed with which the kingdom was founded and the rebellion spread suggests that Hong already had a definite plan of action, and that the uprising was not a spontaneous response to the authorities' oppression.

As the Taipings worked their way north through the Yangtze River Valley, they were joined by whole towns and villages. Hong and Feng organized them into a fanatical but highly disciplined army of more than a million, with separate divisions of men and women soldiers. The Taipings considered men and women equal, but allowed them no contact with one another.

Hong and his followers faced immediate challenges. The local Green Standard Army outnumbered them ten to one, and had recruited the help of river pirates to keep the rebellion contained in Jintian. After a month of preparation, the Taipings managed to break through the blockade and fight their way to the town of Yongan (not to be confused with Yong'an), which fell to them on September 5, 1851.

Hong and his troops rested in Yongan for three months, sustained by local landowners who were hostile to the Manchu Qing Dynasty. During that period, the imperial army regrouped and launched another attack on the Taipings in Yongan. After running out of gunpowder, Hong's followers fought their way out by sword, and laid siege to the city of Guilin. However, the fortifications of Guilin proved too secure, and Hong and his followers eventually gave up and set out northwards, towards Hunan. Here, they encountered an elite militia created by a local member of the gentry specifically to put down peasant rebellions. The two forces fought at Soyi Ford on June 10, 1852, where the Taipings were forced into retreat, and an estimated 20 percent of their troops killed.

T'ien-ching (Heavenly Capital)

On March 10, 1853, Hong’s army captured the central city of Nanking. Hong decided to make the city his permanent capital, and renamed it T'ien-ching (Heavenly Capital). Feng had died on the way to Nanking, and Hung made Yang Hsiu-ch'ing, formerly a firewood salesman from Guangxi, his minister of state. Yang was largely responsible for organizing the new state and planning the strategy of the Taiping armies. Two armies were sent west to secure the Yangtze valley, and two were sent to capture Beijing. The attempt to capture Beijing failed at the outskirts of Tianjin.

Beginning in 1853, Hong began to retreat from political life spent much of his time in meditation or with his harem. Eventually, Yang began to criticize Hong and to usurp his prerogatives as leader. Yang strengthened his authority by appearing to go into trances in which he spoke with the “voice of the Lord.” During one of these trances, he said that the “Lord” ordered Hong to be whipped for kicking one of his concubines. On September 2, 1856, Hong ordered the murder of Yang by another Taiping General, Wei Changhui. When Wei subsequently became arrogant, Hong also had him killed. After the death of Wei, Hong ignored his most capable leaders and instead entrusted his incompetent elder brothers with affairs of the state.

Last Days

The Imperial forces reorganized and began in earnest to re-establish control. In 1862, Hong’s generals warned him that they would not be able to hold T'ien-ching (Nanking) and urged him to abandon the city. Hong refused, and even rejected the storing of supplies for a siege, declaring that God would provide for them.

Hong’s health had begun to deteriorate in 1856. Some sources claim that he committed suicide by ingesting poison on June 1, 1864 after the Chinese authorities finally gained a decisive military advantage and all hope of maintaining his "kingdom" was lost and his body was discovered later in a sewer. Other sources say that he died of illness, possibly food poisoning from eating wild vegetables as food became scarce in the city. Hong’s cousin said that he died after eating “manna;” he had often instructed his followers to eat “manna” in times of starvation. His body was buried in the former Ming Imperial Palace, but was later exhumed by the conquering Chinese general, Zheng, to verify that he was dead. His body was then cremated and the ashes were fired from a cannon, to ensure that he would have no final resting place.

Four months before his death, Hong bequeathed his throne to his eldest son, Hong Tianguifu. The city fell on July 19, 1864, in a terrible slaughter initiated by government troops, which is said to have killed more than 100,000 people.

Most accurate sources put the total deaths during the 15 years of the rebellion at about 20 million civilians and army personnel [1], (some claim the death toll was much higher), more casualties than any war except World War II.

Reforms

Hong and the "Heavenly Kingdom of Transcendent Peace" proclaimed a number of social reforms, including the abolition of private property, state ownership and distribution of land, a classless society, equality of men and women, the replacement of the lunar calendar with a solar calendar, prohibition of foot-binding, and laws prohibiting opium, gambling, tobacco, alcohol, polygamy (including concubinage), slavery, and prostitution. The subject of study for the civil service examinations for officials was changed from the Confucian classics to the Christian Bible, and women were admitted to the examinations.

Implementation of these laws, however, was ineffective, haphazard and brutal; all efforts were concentrated on the army, and civil administration was very disorganized. In spite of the prohibition of polygamy, Taiping leaders lived as kings and maintained harems; it is believed that Hong had 88 concubines.

Publications

- The Imperial Decree of Taiping《太平詔書》(1852)

- The Instructions on the Original Way Series (《原道救世訓》系列) (1845 - 1848): included in The Imperial Decree of Taiping later. The series is proclaimed by PRC's National Affairs Department (國務院) to be Protected National Significant Documents (全國重點文物) in 1988.

- The Instructions on the Original Way to Save the World (《原道救世訓》)

- The Instructions on the Original Way to Awake the World (《原道醒世訓》)

- The Instructions on the Original Way to Make the World Realize (《原道覺世訓》)

- The New Essay on Economics and Politics (《資政新篇》 ) (1859)

Quotes

The following poem, called "The Poem on Executing the Vicious and Preserving the Righteous" (《斬邪留正詩》), written in 1837 by Hong, illustrates his religious thinking and goal that later lead to the establishment the "Heavenly Kingdom of Taiping." Note that the second last line mentions Taiping, the name of the yet—to-be-proclaimed kingdom. Some Chinese scholars considered this, and other poems of his, as being of poor quality, because they lack of use of classical phrases.

- Holding the Universe in the hand,

- I slay evil, preserve justice, and improve the lives of my subjects.

- Eyes can see through beyond the west, the north, the rivers, and the mountains,

- Sounds can shake the east, the south, the Sun, and the Moon.

- The glorious sword of authority was given by Lord,

- Poems and books are evidences that praise Yahweh in front of Him.

- Taiping [perfect Peace] unifies the World of Light,

- The domineering air will be joyous for myriads of thousand years.

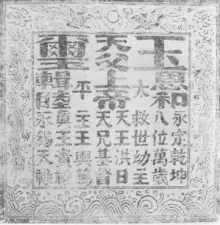

手握乾坤殺伐權,斬邪留正解民懸。眼通西北江山外,聲振東南日月邊。璽劍光榮存帝賜,詩章憑據誦爺前,太平一統光世界,威風快樂萬千年

Legacy

Mao Zedong praised Hong and asserted the legitimacy of his Taiping Kingdom, perhaps in an effort to legitimize his own rise to power. Hong has also been compared to Li Hongzhi, the leader of Falun Gong, because he rallied a large number of people behind a religious or spiritual cause. Although the Taiping Rebellion initially began as a spiritual movement, the majority of the Taiping Army came almost exclusively from the lower classes and was made up of minorities such as the Hakka and Zhuang, whose motivation for joining the rebellion was primarily political.

In his birthplace, in 1959, the Peoples Republic of China established a small museum called Hong Xiuquan's Former Residence Memorial Museum (洪秀全故居紀念館), where there is a longan tree planted by him. The museum's plate is written by the famous literary figure, Guo Moruo (郭沫若) (1892–1978). The residence and Book Chamber Building were renovated in 1961.

Notes

- ↑ J. Gray. Rebellions and Revolutions: China from the 1800s to the 1980s. (Oxford University Press, 1990), 55.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Doezema, William R. 1993. Western seeds of eastern heterodoxy: the impact of Protestant revivalism on the Christianity of Taiping rebel leader Hung Hsiu-ch'üan, 1836-1864. Grand Rapids, MI: Conference on Faith and History.

- Gray, Jack. 1990. Rebellions and Revolutions: China from the 1800s to the 1980s. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198215762.

- Hamberg, Theodore. 1995. The Chinese rebel chief, Hung-Siu-Tsuen and the origin of the insurrection in China. London: Walton and Maberly.

- Spence, Jonathan D. 1996. God's Chinese son: the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom of Hong Xiuquan. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0393038440

- __________. 1998. The Taiping vision of a Christian China, 1836-1864. Waco, TX: Markham Press Fund, Baylor University Press. ISBN 0585110042

- Wills, John E. 1994. Mountain of fame: portraits in Chinese history. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691055424

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.