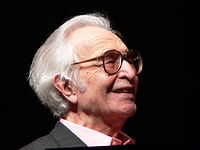

Dave Brubeck

| Dave Brubeck | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Born | December 6, 1920 |

| Died | December 5, 2012 (aged 91) |

| Genre(s) | Jazz Cool jazz West Coast jazz Third stream |

| Occupation(s) | Pianist Composer Bandleader |

| Instrument(s) | Piano |

| Website | www.davebrubeck.com |

David Warren "Dave" Brubeck (December 6, 1920 – December 5, 2012) was an American jazz pianist and composer, considered to be one of the foremost exponents of progressive jazz. Brubeck's style ranged from refined to bombastic, reflecting his mother's attempts at classical training and his improvisational skills. Brubeck's popularity was widespread both geographically, as he toured extensively throughout the United States and internationally, and in terms of audience. While jazz, particularly pieces as complex and unusual as those favored by Brubeck, was often considered challenging and popular only with a limited audience, Brubeck played on college campuses and expanded his audience to students and young adults making cool jazz widely appreciated.

His music is known for employing unusual time signatures, and superimposing contrasting rhythms, meters, and tonalities. Brubeck experimented with time signatures throughout his career. His long-time musical partner, alto saxophonist Paul Desmond, wrote the saxophone melody for the Dave Brubeck Quartet's best remembered piece, "Take Five", which is in 5/4 time. This piece has endured as a jazz classic on one of the top-selling jazz albums, Time Out.

Brubeck was also a recognized composer, with compositions that ranged from jazz pieces to more classical orchestral and sacred music, always interweaving his beloved jazz with more classical forms. Many of these compositions reflected and developed his spiritual beliefs; he became a Catholic in 1980 shortly after completing the Mass To Hope! A Celebration.

Life

Dave Brubeck was born December 6, 1920 in the San Francisco Bay Area city of Concord, California. His father, Peter Howard "Pete" Brubeck, was a cattle rancher, and his mother, Elizabeth (née Ivey), who had studied piano in England under Myra Hess and intended to become a concert pianist, taught piano for extra money.[1] His father had Swiss ancestry (the family surname was originally "Brodbeck"), while his maternal grandparents were English and German, respectively.[2][3] Brubeck originally did not intend to become a musician (his two older brothers, Henry and Howard, were already on that track), but took piano lessons from his mother. He could not read music during these early lessons, attributing this difficulty to poor eyesight, but "faked" his way through, well enough that this deficiency went unnoticed for many years.[4]

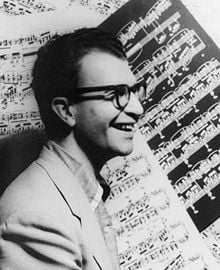

1954[5]]] When Dave was 12 the Brubeck family moved to a cattle ranch in Ione, California near the foothills of the Sierras. Dave Brubeck worked on the ranch during his teenage years, and performed with a local dance band at the weekends. Although he was passionate about music, he planned a more practical career. Intending to work with his father on their ranch, Brubeck entered the College of the Pacific in Stockton, California (now the University of the Pacific), studying veterinary science. He changed to music on the urging of the head of zoology, Dr. Arnold, who told him "Brubeck, your mind's not here. It's across the lawn in the conservatory. Please go there. Stop wasting my time and yours."[6] Later, Brubeck was nearly expelled when one of his professors discovered that he could not read music. Several of his professors came forward, arguing that his ability with counterpoint and harmony more than compensated. The college was still afraid that it would cause a scandal and embarrass the school, finally agreeing to let Brubeck graduate only after he had promised never to teach.[7]

Brubeck married Iola Whitlock, a fellow student at the College of the Pacific, in September 1942. They had six children, five of whom became professional musicians, often joining Brubeck in concerts and in the recording studio. Darius, the eldest, became a pianist, producer, educator and performer. He was named after Dave Brubeck's mentor Darius Milhaud.[8] Dan became a percussionist, Chris a multi-instrumentalist and composer, and Matthew, the youngest, a cellist with an extensive list of composing and performance credits; Michael, who died in 2009, was a saxophonist.[9]

After graduating in 1942, Brubeck was drafted into the U.S. Army. He served in Europe in the Third Army. He volunteered to play piano at a Red Cross show and was such a hit that he was spared from combat service and ordered to form a band. He created one of the U.S. armed forces' first racially integrated bands, "The Wolfpack".[7] Brubeck's experiences in the war led him to serious religious questions about the meaning of life and death, which informed many of his compositions.[10]

He returned to college after the war, this time attending Mills College in Oakland, California. There he studied under Darius Milhaud, who encouraged him to study fugue and orchestration, but not classical piano. While on active duty, he received two lessons from Arnold Schoenberg at UCLA in an attempt to connect with High Modernism theory and practice.[11] After completing his studies under Milhaud, who encouraged Brubeck to pursue jazz, Brubeck worked with an octet and later formed a trio, including Cal Tjader and Ron Crotty from the octet.

In 1951, Brubeck damaged his spinal cord and several vertebrae while diving into the surf in Hawaii. He would later remark that the paramedics who attended had described him as a "DOA" (dead on arrival). Brubeck recovered after a few months, but suffered with residual nerve pain in his hands for years after.[9] The injury also influenced his playing style towards complex, blocky chords rather than speedy, high dexterity, single-note runs.

After his recovery, Brubeck formed the Dave Brubeck Quartet with Paul Desmond on alto saxophone. Their collaboration and friendship outlasted the 17-year life of the Quartet, which was disbanded in 1967, continuing until Desmond's death in 1977. The Quartet was popular on college campuses, introducing jazz to thousands of young people, as well as playing in major cities throughout the United States as well as internationally. Such was Brubeck's fame and influence that he was featured on the cover of Time Magazine in 1954. The Quartet's 1959 recording Time Out became the first jazz album to sell over a million copies.[12]

After the original Quartet was dissolved, Brubeck continued recording and touring, as well as composing. His performances included several at the White House, for many different Presidents.[13]

Brubeck became a Catholic in 1980, shortly after completing the Mass To Hope which had been commissioned by Ed Murray, editor of the national Catholic weekly Our Sunday Visitor. His first version of the piece did not include the Our Father, an omission pointed out to him by a priest after its premiere and subsequently in a dream. Brubeck immediately added it to the Mass, and joined the Catholic Church "because I felt somebody's trying to tell me something." Although he had spiritual interests before that time, he said, "I didn't convert to Catholicism, because I wasn't anything to convert from. I just joined the Catholic Church."[10] In 2006, Brubeck was awarded the University of Notre Dame's Laetare Medal, the oldest and most prestigious honor given to American Catholics, during the University's commencement.[14] He performed "Travellin' Blues" for the graduating class of 2006.

In 2008 Brubeck became a supporter of the Jazz Foundation of America in its mission to save the homes and the lives of elderly jazz and blues musicians, including those who had survived Hurricane Katrina.[15]

Brubeck died of heart failure on December 5, 2012, in Norwalk, Connecticut, one day before his 92nd birthday. He was on his way to a cardiology appointment, accompanied by his son Darius.[16] A birthday party had been planned for him with family and famous guests.[17]

Career

Brubeck had a long career as a jazz musician, receiving numerous awards and honors. He had a style that reflected both his classical training and his own improvisational skills.

Early musical career

After completing his studies, Brubeck formed the Dave Brubeck Octet with fellow classmates. They made several recordings but had little success with their highly experimental approach to jazz. Brubeck then formed a trio, including Cal Tjader and Ron Crotty from the octet. Their music was popular in San Francisco, and their records began to sell.[18]

Unfortunately, in 1951 Brubeck suffered a serious back injury which incapacitated him for several months, and the trio had to disband.

Dave Brubeck Quartet

Brubeck organized the Dave Brubeck Quartet later in 1951, with Paul Desmond on alto saxophone. They took up a long residency at San Francisco's Black Hawk nightclub and gained great popularity touring college campuses, recording a series of albums with such titles as Jazz at Oberlin (1953), Jazz at the College of the Pacific (1953), and Brubeck's debut on Columbia Records, Jazz Goes to College (1954).

Early bassists for the group included Ron Crotty, Bob Bates, and Bob's brother Norman Bates; Lloyd Davis and Joe Dodge held the drum chair. In 1956 Brubeck hired drummer Joe Morello, who had been working with Marian McPartland; Morello's presence made possible the rhythmic experiments that were to come. In 1958 African-American bassist Eugene Wright joined for the group's U.S. Department of State tour of Europe and Asia. Wright became a permanent member in 1959, making the "classic" Quartet's personnel complete. During the late 1950s and early 1960s Brubeck canceled several concerts because the club owners or hall managers continued to resist the idea of an integrated band on their stages. He also canceled a television appearance when he found out that the producers intended to keep Wright off-camera.[19]

In 1959, the Dave Brubeck Quartet recorded Time Out, an album about which the record label was enthusiastic but which they were nonetheless hesitant to release. Featuring the album art of S. Neil Fujita, the album contained all original compositions, including "Take Five," "Blue Rondo à la Turk," and "Three To Get Ready," almost none of which were in common time: 9/8, 5/4, 3/4, and 6/4 were used.[20] Nonetheless, it quickly went platinum, becoming the first jazz album to sell more than a million copies.[12][21] "Take Five" was written by Brubeck's long-time musical partner, alto saxophonist Paul Desmond, and used the unusual quintuple (5/4) time, from which its name is derived. This piece, which became the Quartet's most famous performance piece as well as being recorded by the them several times, is famous for Desmond's distinctive saxophone melody and imaginative, jolting drum solo by Joe Morello.

Time Out was followed by several albums with a similar approach, including Time Further Out: Miro Reflections (1961), using more 5/4, 6/4, and 9/8, plus the first attempt at 7/4; Countdown: Time in Outer Space (dedicated to John Glenn) (1962), featuring 11/4 and more 7/4; Time Changes (1963), with much 3/4, 10/4 (which was really 5+5), and 13/4; and Time In (1966). These albums (except the last) were also known for using contemporary paintings as cover art, featuring the work of Joan Miró on Time Further Out, Franz Kline on Time in Outer Space, and Sam Francis on Time Changes.

Apart from the "College" and the "Time" series, Brubeck recorded four LPs featuring his compositions based on the group's travels, and the local music they encountered. Jazz Impressions of the USA (1956, Morello's debut with the group), Jazz Impressions of Eurasia (1958), Jazz Impressions of Japan (1964), and Jazz Impressions of New York (1964) are less well-known albums, but all are brilliant examples of the quartet's studio work, and they produced Brubeck standards such as "Summer Song," "Brandenburg Gate," "Koto Song," and "Theme From Mr. Broadway."

Brubeck and his wife Iola developed a jazz musical, The Real Ambassadors, based in part on experiences they and their colleagues had during foreign tours on behalf of the Department of State. The soundtrack album, which featured Louis Armstrong, Lambert, Hendricks & Ross, and Carmen McRae was recorded in 1961; the musical was performed at the 1962 Monterey Jazz Festival.

The final studio album for Columbia by the Desmond/Wright/Morello quartet was Anything Goes (1966) featuring the songs of Cole Porter. A few concert recordings followed, and The Last Time We Saw Paris (1967) was the "Classic" Quartet's swan-song.

Composer

Brubeck's disbanding of the Quartet at the end of 1967 (although he continued touring and performing until the end of his life) allowed him more time to compose the longer, extended orchestral and choral works that were occupying his attention. February 1968 saw the premiere of The Light in the Wilderness for baritone solo, choir, organ, the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra conducted by Erich Kunzel, and Brubeck improvising on certain themes within. The next year, Brubeck produced The Gates of Justice, a cantata mixing Biblical scripture with the words of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. He also composed for – and performed with his ensemble on – "The NASA Space Station," a 1988 episode of the CBS TV series This Is America, Charlie Brown.[22]

Awards

Brubeck received numerous awards and honors during his long career. These include the National Medal of Arts from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Smithsonian Medal, a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, and a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences (1996). International honors include the Bocconi Medal from Italy, Austria's highest award for the Arts, and the London Symphony Orchestra Lifetime Achievement Award (2007).[13]

In 1954, Brubeck was featured on the cover of Time, the second jazz musician to be so honored (the first was Louis Armstrong on February 21, 1949).[23] Brubeck personally found this accolade embarrassing, since he considered Duke Ellington more deserving of it and was convinced that he had been favored for being Caucasian.[20]

In 2004, Brubeck was awarded an honorary Doctor of Sacred Theology degree from the University of Fribourg, Switzerland, in recognition of his contributions to the canon of sacred choral music. While Brubeck has received several honorary degrees, it is highly unusual a jazz musician to receive an honorary doctorate in Sacred Theology. On receiving the degree, Brubeck noted:

I am very aware of how little I know compared to the theologians of the world. When I have been asked to set certain sacred texts to music, I immediately study the history of the text and try to understand the words. Then, I plunge in to find the core and set it to music. To people who know me only as a jazz musician, this honor must seem very strange. However, there is a body of orchestral and choral work, going back to 1968 and my first oratorio ’The Light in the Wilderness’ which may help people understand the justification for this unexpected honor. I am both humbled and deeply grateful.[24]

Brubeck recorded five of the seven tracks of his album Jazz Goes to College in Ann Arbor. He returned to Michigan many times, including a performance at Hill Auditorium where he received a Distinguished Artist Award from the University of Michigan's Musical Society in 2006.

On April 8, 2008, United States Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice presented Brubeck with a "Benjamin Franklin Award for Public Diplomacy" for offering an American "vision of hope, opportunity and freedom" through his music. The State Department said in a statement that "as a pianist, composer, cultural emissary and educator, Dave Brubeck's life's work exemplifies the best of America's cultural diplomacy."[25] "As a little girl I grew up on the sounds of Dave Brubeck because my dad was your biggest fan," said Rice.[26] At the ceremony Brubeck played a brief recital for the audience at the State Department. "I want to thank all of you because this honor is something that I never expected. Now I am going to play a cold piano with cold hands," Brubeck stated.[25]

On October 18, 2008, Brubeck received an honorary Doctor of Music degree from the prestigious Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York.[27]

In December 2008, Brubeck was inducted into the California Hall of Fame at The California Museum California. Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and First Lady Maria Shriver presided over the ceremony.[28]

On September 20, 2009, at the Monterey Jazz Festival, Brubeck was awarded an honorary Doctor of Music degree (D.Mus. honoris causa) from Berklee College of Music.[29]

In September 2009, the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts announced Brubeck as a Kennedy Center Honoree for exhibiting excellence in performance arts.[30] The Kennedy Center Honors Gala took place on Sunday, December 6 (Brubeck's 89th birthday), and was broadcast nationwide on CBS on December 29. When the award was made, President Barack Obama, recalling a 1971 concert Brubeck had given in Honolulu, said, "You can’t understand America without understanding jazz, and you can’t understand jazz without understanding Dave Brubeck."[9]

On May 16, 2010, Brubeck was awarded an honorary Doctor of Music degree (honoris causa) from The George Washington University in Washington, D.C. The ceremony took place on the National Mall.[31] [32]

On July 5, 2010, Brubeck was awarded the Miles Davis Award at the Montreal International Jazz Festival.[33] In 2010, Bruce Ricker and Clint Eastwood produced Dave Brubeck: In His Own Sweet Way, a documentary about Brubeck for Turner Classic Movies (TCM) to commemorate his 90th birthday in December 2010.[34]

Legacy

Immediately following Brubeck's death, the media posted tributes to his work. The Los Angeles Times noted that he "was one of Jazz's first pop stars."[35] The New York Times noted he had continued to play well into his old age, performing in 2011 and in 2010 only a month after getting a pacemaker, with Times music writer Nate Chinen commenting that Brubeck had replaced "the old hammer-and-anvil attack with something almost airy" and that his playing at the Blue Note Jazz Club in New York City was "the picture of judicious clarity".[36]

In The Daily Telegraph, music journalist Ivan Hewett wrote: "Brubeck didn’t have the réclame of some jazz musicians who lead tragic lives. He didn’t do drugs or drink. What he had was endless curiosity combined with stubbornness," adding "His work list is astonishing, including oratorios, musicals and concertos, as well as hundreds of jazz compositions. This quiet man of jazz was truly a marvel."[37] In The Guardian, John Fordham said "Brubeck's real achievement was to blend European compositional ideas, very demanding rhythmic structures, jazz song-forms and improvisation in expressive and accessible ways. His son Chris told the Guardian "when I hear Chorale, it reminds me of the very best Aaron Copland, something like Appalachian Spring. There's a sort of American honesty to it."[38]

Brubeck founded the Brubeck Institute with his wife, Iola, at their alma mater, the University of the Pacific in 2000. What began as a special archive, consisting of the personal document collection of the Brubecks, has since expanded to provide fellowships and educational opportunities in jazz for students, also leading to having one of the main streets on which the school resides named in his honor, Dave Brubeck Way.[39]

Discography

- Dave Brubeck - Jazz At College Of The Pacific, Vol. 2 (c. 1942), Original Jazz Classics: OJCCD 1076-2[40]

- Brubeck Trio with Cal Tjader, Volume 1 (1949)

- Brubeck Trio with Cal Tjader, Volume 2 (1949)

- Brubeck/Desmond (1951)

- Stardust (1951)

- Dave Brubeck Quartet (1952)

- Jazz at the Blackhawk (1952)

- Dave Brubeck/Paul Desmond (1952)

- Jazz at Storyville (live) (1952)

- Featuring Paul Desmond in Concert (live) (1953)

- Two Knights at the Black Hawk (1953)

- Jazz at Oberlin (1953) Fantasy Records

- Dave Brubeck & Paul Desmond at Wilshire Ebell (1953)

- Jazz at the College of the Pacific (1953) Fantasy Records

- Jazz Goes to College (1954) Columbia Records

- Dave Brubeck at Storyville 1954 (live) (1954)

- Brubeck Time (1955)

- Jazz: Red Hot and Cool (1955)

- Brubeck Plays Brubeck (1956)

- Dave Brubeck and Jay & Kai at Newport (1956)

- Jazz Impressions of the U.S.A. (1956)

- Plays and Plays and... (1957) Fantasy Records

- Reunion (1957) Fantasy Records

- Jazz Goes to Junior College (live) (1957)

- Dave Digs Disney (1957)

- In Europe (1958)

- Complete 1958 Berlin Concert (released 2008)

- Newport 1958

- Jazz Impressions of Eurasia (1958)

- Gone with the Wind (1959) Columbia Records

- Time Out (1959) Columbia Records/Legacy (RIAA: Platinum)

- Southern Scene (1960)

- The Riddle (1960)

- Brubeck and Rushing (1960)

- Brubeck a la Mode (1961) Fantasy Records

- Tonight Only with the Dave Brubeck Quartet (1961, with Carmen McRae)

- Take Five Live (1961, Live, Columbia Records, with Carmen McRae, released 1965)

- Near-Myth (1961) Fantasy Records

- Bernstein Plays Brubeck Plays Bernstein (1961)

- Time Further Out (1961) Columbia Records/Legacy

- Countdown—Time in Outer Space (1962) Columbia Records

- The Real Ambassadors (1962)

- Music from West Side Story (1962)

- Bossa Nova U.S.A. (1962)

- Brubeck in Amsterdam (1962, released 1969)

- Brandenburg Gate: Revisited (1963) Columbia Records

- At Carnegie Hall (1963)

- Time Changes (1963)

- Dave Brubeck in Berlin (1964)

- Jazz Impressions of Japan (1964) Columbia Records/Legacy

- Jazz Impressions of New York (1964) Columbia Records/Legacy

- Angel Eyes (1965)

- My Favorite Things (1965)

- The 1965 Canadian Concert (released 2008)

- Time In (1966) Columbia Records

- Anything Goes (1966)

- Bravo! Brubeck! (1967)

- Buried Treasures (1967, released 1998)

- Jackpot (1967) Columbia Records

- The Last Time We Saw Paris (1968)

- Adventures in Time (Compilation, 1972) Columbia Records

- The Light in the Wilderness (1968)

- Compadres (1968)

- Blues Roots (1968)

- Brubeck/Mulligan/Cincinnati (1970)

- Live at the Berlin Philharmonie (1970)

- The Last Set at Newport (1971) Atlantic Records

- Truth Is Fallen (1972)

- We're All Together Again for the First Time (1973)

- Two Generations of Brubeck (1973)

- Brother, the Great Spirit Made Us All (1974)

- All The Things We Are (1974)

- Brubeck & Desmond 1975: The Duets

- DBQ 25th Anniversary Reunion (1976) A&M Records

- The New Brubeck Quartet Live at Montreux (1978)

- A Cut Above (1978)

- La Fiesta de la Posada (1979)

- Back Home (1979) Concord Records

- A Place in Time (1980)

- Tritonis (1980) Concord Records

- To Hope! A Celebration by Dave Brubeck (A Mass in the Revised Roman Ritual) – Original now out-of-print 1980 recording conducted by Erich Kunzel. Pastoral Arts Associates (PAA) of North America, Old Hickory, Nashville, Tennessee 37187 LP record number DRP-8318. Music Copyright 1979 St. Francis Music. Recording Copyright 1980 Our Sunday Visitor, Inc.

- Paper Moon (1982) Concord Records

- Concord on a Summer Night (1982)

- For Iola (1984)

- Marian McPartland's Piano Jazz with Guest Dave Brubeck (1984, released 1993)

- Reflections (1985)

- Blue Rondo (1986)

- Moscow Night (1987)

- New Wine (1987, released 1990)

- The Great Concerts (Compilation, 1988)

- Quiet as the Moon (Charlie Brown soundtrack) (1991)

- Once When I Was Very Young (1991)

- Time Signatures: A Career Retrospective (Compilation, 1992) Sony Columbia Legacy

- Trio Brubeck (1993)

- Late Night Brubeck (1994)

- Just You, Just Me (solo) (1994)

- Nightshift (1995)

- Young Lions & Old Tigers (1995) Telarc

- To Hope! A Celebration (1996)

- A Dave Brubeck Christmas (1996)

- In Their Own Sweet Way (1997)

- So What's New? (1998)

- The 40th Anniversary Tour of the U.K. (1999)

- One Alone (2000)

- Double Live from the USA & UK (2001)

- The Crossing (2001)

- Vocal Encounters (Compilation, 2001) Sony Records

- Classical Brubeck (with the London Symphony Orchestra, 2003) Telarc

- Park Avenue South (2003)

- The Gates of Justice (2004)

- Private Brubeck Remembers (solo piano + Interview disc w. Walter Cronkite) (2004)

- London Flat, London Sharp (2005) Telarc

- Indian Summer (2007) Telarc

- Live at the Monterey Jazz Festival 1958–2007 (2008)

- Yo-Yo Ma & Friends Brubeck tracks: Joy to the World, Concordia (2008) Sony BMG

- Everybody Wants to Be a Cat: Disney Jazz Volume 1 Brubeck tracks: "Some Day My Prince Will Come," "Alice in Wonderland" (with Roberta Gambarini) (2011)

- Their Last Time Out (DBQ recorded Live, 12/26/67) (2011)

Notes

- ↑ Ilse Storb, Jazz Meets the World – The World Meets Jazz (Berlin: LIT Verlag, 2000, ISBN 978-3825837488).

- ↑ Ancestry of Dave Brubeck Wargs.com. Retrieved December 20, 2012.

- ↑ Dave Brubeck NEA Jazz Master (1999) Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview, August 2007. Retrieved December 20, 2012.

- ↑ Sara Fishko, An Hour With Dave Brubeck WNYC, 2004. Retrieved December 20, 2012.

- ↑ Music: The Man on Cloud No. 7 (cover story) Time, November 8, 1954. Retrieved December 20, 2012.

- ↑ Fred Hall, It's About Time: The Dave Brubeck Story (University of Arkansas Press, 1996, ISBN 978-1557284051).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 From Cowboy To Jazzman (Getting Started) Rediscovering Dave Brubeck, PBS. Retrieved December 20, 2012.

- ↑ Darius Brubeck – Piano Rediscovering Dave Brubeck, PBS. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Dave Brubeck, worldwide ambassador of jazz, dies at 91 The Washington Post, December 6, 2012. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Brubeck Rediscovers Himself, Rediscovering Dave Brubeck, PBS. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ Kevin Starr, Golden dreams: California in an age of abundance, 1950–1963 (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0195153774).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Time Out Sesssions, NYC, 1959 Jazz.com. Retrieved December 20, 2012.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 About Dave DaveBrubeck.com. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ↑ Michael O. Garvey, Jazz legend Dave Brubeck to receive Laetare Medal Notre Dame Office News, March 25, 2006. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ Allaboutjazz.com Dave Brubeck, Hank Jones and Norah Jones Perform at Jazz Foundation of America's "A Great Night in Harlem" Benefit on May 29th All about Jazz Publicity, April 29, 2008. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ Howard Reich, Dave Brubeck: A jazz icon who reached a massive audience Chicago Tribune, December 5, 2012. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ Ann Oldenburg, Jazz great Dave Brubeck dies in Connecticut USA Today, December 5, 2012. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ Ted Gioia, West Coast Jazz: Modern Jazz in California 1945–1960 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0520217294).

- ↑ Henry Grabar, How Dave Brubeck Used His Talents to Fight for Integration The Atlantic Cities, December 5, 2012. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Fred Kaplan, 1959: The Year Everything Changed (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2009, ISBN 978-0470387818).

- ↑ Martin Chilton, Dave Brubeck, Take Five jazz star, dies 91 The Daily Telegraph, December 5, 2012. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ↑ Ethan Minovitz, Take Five Jazz Great Dave Brubeck Dead at 91 Big Cartoon DataBase, December 11, 2012. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ Time magazine cover: Louis Armstrong – February 21, 1949. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ Jazz Legend Dave Brubeck Receives Honorary Doctorate In Sacred Theology From University Of Fribourg, Switzerland University of Fribourg, November 15, 2004. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Jazz great Brubeck wins US public diplomacy award, AFP, April 8, 2008. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ "Whatever Happened to Cultural Diplomacy?", All About Jazz, April 19, 2008. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ Organ Debut, Honorary Degree for Jazz Great Dave Brubeck Highlight Eastman Weekend Celebration Eastman School of Music, October 3, 2008. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ↑ Gabrielle Levy, Remembering Dave Brubeck, jazz legend UPI.com, December 5, 2012. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ Margot Edwards, Dave Brubeck to Receive Honorary Doctorate Berklee College of Music, August 19, 2009. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ Jacqueline Trescott, Kennedy Center Honorees for 2009 Are: Mel Brooks, Robert De Niro, Grace Bumbry, Bruce Springsteen and Dave Brubeck The Washington Post, September 10, 2009. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- ↑ "The George Washington University’s Commencement Line-Up Finalized - A. James Clark and Legendary Pianist and Composer Dave Brubeck to Receive Honorary Degrees; First Lady Michelle Obama to Headline Weekend Celebration," George Washington University, April 21, 2010. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ↑ Legendary Pianist and Composer Dave Brubeck to Receive Honorary Degree from The George Washington University The George Washington University, Media Relations.

- ↑ Miles Davis Award MontrealJazzFest.com. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ↑ Lee Mergner, In Dave Brubeck's Own Sweet Way JazzTimes, November 29, 2010. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ↑ August Brown, Jazz great Dave Brubeck dies at 91 Los Angeles Times, December 5, 2012. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ↑ Ben Ratliff, Dave Brubeck, Whose Distinctive Sound Gave Jazz New Pop, Dies at 91 The New York Times, December 5, 2012. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ↑ Ivan Hewett, Dave Brubeck: Endless curiosity combined with stubbornness The Daily Telegraph, December 6, 2012. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ↑ John Fordham, Dave Brubeck obituary The Guardian, December 5, 2012. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ↑ Brubeck Summer Jazz Colony, University of the Pacific. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ↑ Dave Brubeck Catalog jazzdisco.org. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Gioia, Ted. West Coast Jazz: Modern Jazz in California, 1945-1960. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0520217294

- Hall, Fred. It's About Time: The Dave Brubeck Story. University of Arkansas Press, 1996. ISBN 978-1557284051

- Kaplan, Fred. 1959: The Year Everything Changed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2009. ISBN 978-0470387818

- Starr, Kevin. Golden Dreams: California in an Age of Abundance, 1950-1963. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0195153774

- Storb, Ilse. Jazz Meets the World – The World Meets Jazz. Berlin: LIT Verlag, 2000. ISBN 978-3825837488

External links

All links retrieved January 25, 2024.

- DaveBrubeck.com - Official Website

- Dave Warren Brubeck at Find-a-Grave.

- Dave Brubeck at the Internet Movie Database

- Rediscovering Dave Brubeck PBS, December 16, 2001 documentary.

- Dave Brubeck biography and concert review Cosmopolis.

- "Q&A Special: Dave Brubeck, a Life in Music" theartsdesk.com.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.