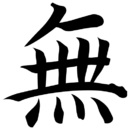

Zen

"Zen" is the Japanese pronunciation of the character "禅" which is pronounced "chán" in Mandarin Chinese. The same character is read "Sŏn" in Korean. Zen is a contraction of the seldom-used long form zenna (禅那; Mandarin: chánnà), which derives from "dhyānam" (Sanskrit) or "jhānam" (Pāli), meaning meditation.

History

Origination and Development in China

The establishment of the Chan school of Buddhism is traditionally attributed to Bodhidharma, who, according to legend, arrived in China sometime between 460 and 527 B.C.E.[1] Bodhidharma is recorded as having come to China to teach a "special transmission outside scriptures" which "did not rely upon words," which was then transmitted through a series of Chinese patriarchs, the most famous of whom was the Sixth Patriarch, Huineng.

The sixth patriarch's importance is attested to in his (likely hagiographical) biography, which states that his virtue and wisdom were so great that Hongren (the fifth patriarch) chose him (a layman) over many senior monks as the next leader of the movement. This appointment led to seething jealousy and bitter recriminations among Hongren's students, which presaged a division between Huineng's followers and those of Hongren's senior pupil (Shenxiu). This rift persisted until the middle of the 8th century, with monks of Huineng's intellectual lineage, who called themselves the Southern school, opposing those followed Hongren's student Shenxiu (神秀). The Southern school eventually became predominant, which led to the eventual disintegration of competing lineages.

It should be noted that, despite the attribution of the tradition to an Indian monk, most scholars acknowledge that Chan was, in fact, an indigenous Chinese development that fused Daoist sensibilities with Buddhist metaphysics. As Wright argues:

- the distrust of words, the rich store of concrete metaphor and analogy, the love of paradox, the bibliophobia, the belief in the direct, person-to-person, and often world-less communication of insight, the feeling that life led in close commuinion with nature is conducive to enlightenment – all these are colored with Taoism (Wright, 78. See also Ch'en, 213).

Further, since the tradition only entered the realm of fully documented history with the debates between the Southern school and the followers of Shenxiu, many Western scholars suggest that the early Zen patriarchs are better understood as legendary figures.

Regardless of these historical-critical issues, the centuries following the ascendence of the Southern school was marked by the Chan school's growth into one of the largest sects of Chinese Buddhism. The teachers claiming Huineng's posterity began to branch off into numerous different schools, each with their own special emphases, but who all kept the same basic focus on meditational practice, individual instruction and personal experience. During the late Tang and the Song periods, the tradition truly flowered, as a wide number of eminent monks developed specialized teachings and methods, which, in turn, crystallized into the five houses (五家) of mature Chinese Zen: Caodong (曹洞宗), Linji (臨濟宗), Guiyang (潙仰宗), Fayan (法眼宗), and Yunmen (雲門宗). In addition to these doctrinal and pedagogical developments, the Tang period also a fruitful interaction between Chan (with its minimalistic and naturalistic tendencies) and Chinese art, calligraphy and poetry.

Over the course of Song Dynasty (960-1279), the Guiyang, Fayan, and Yunmen schools were gradually absorbed into the Linji. During the same period, Zen teaching began to incorporate an innovative and unique technique for reaching enlightenment: gong-an (Japanese: koan) practice (described below). [2] While koan practice was a prevalent form of instruction in the Linji school, it was also came to be employed on a more limited basis by the Caodong school. The singluar teachings of these Song-era masters came to be documented in various texts, including the Blue Cliff Record (1125) and The Gateless Gate (1228). Many of these texts are still studied today.

Chan continued to be an influential religious force in China, although some energy was lost to the syncretist Neo-Confucian revival of Confucianism, which began in the Song period (960-1279). While traditionally distinct, Chan was taught alongside Pure Land Buddhism in many Chinese Buddhist monasteries. In time, much of this distinction was lost, and many masters taught both Chan and Pure Land. In the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), Chan Buddhism enjoyed something of a revival under luminaries such as Hanshan Deqing (憨山德清), who wrote and taught extensively on both Chan and Pure Land Buddhism; Miyun Yuanwu (密雲圓悟), who came to be seen posthumously as the first patriarch of the Obaku Zen school; as well as Yunqi Zhuhong (雲棲株宏) and Ouyi Zhixu (藕溢智旭).

After further centuries of decline, Chan was revived again in the early 20th century by Hsu Yun, who stands out as the defining figure of 20th century Chinese Buddhism. Many well known Chan teachers today trace their lineage back to Hsu Yun, including Sheng-yen and Hsuan Hua, who have propagated Chan in the west where it has grown steadily through the 20th and 21st century.

It was severely repressed in China during the recent modern era with the appearance of the People's Republic, but has more recently been re-asserting itself on the mainland, and has a significant following in Taiwan and Hong Kong and among Overseas Chinese.[3]

Zen in Vietnam

Zen, which emerged as a distinctively Chinese interpretation of Buddhism, became an international phenomenon early in its history. The pan-national spread of these doctrines first occurred in Vietnam, whose traditions posit that, in 580, an Indian monk named Vinitaruci (Vietnamese: Tì-ni-đa-lưu-chi) arrived in their country after completing his studies with Sengcan, the third patriarch of Chinese Zen. The school founded by Vinitaruci and his lone Vietnamese disciple is the oldest known branch of Vietnamese Zen (Thien (thiền) Buddhism). By the 10th century (and after a period of obscurity), the Vinitaruci School became one of the most influential Buddhist groups in Vietnam, particularly so under the patriarch Vạn-Hạnh (died 1018). Other early Vietnamese Zen schools included the Vo Ngon Thong (Vô Ngôn Thông), which was associated with the teaching of Mazu (a famed Chinese master), and the Thao Duong (Thảo Đường), which incorporated nianfo chanting techniques; both were founded by itinerant Chinese monks. These three schools of early Thien Buddhism were profoundly disrupted by the Mongol invasions of the 13th century, and the tradition remained nearly dormant until the founding of a new school by one of Vietnam's religious kings. This was the Truc Lam (Trúc Lâm) school, which evinced a deep influence from Confucian and Taoist philosophy. Nevertheless, Truc Lam's prestige waned over the following centuries as Confucianism became dominant in the royal court. In the 17th century, a group of Chinese monks led by Nguyen Thieu (Nguyên Thiều) established a vigorous new school, the Lam Te (Lâm Tế), which is the Vietnamese pronunciation of Linji. A more domesticated offshoot of Lam Te, the Lieu Quan (Liễu Quán) school, was founded in the 18th century and has since been the predominant branch of Vietnamese Zen.

Zen in Korea

Zen Buddhism began to appear in Korea in the 9th century, with the first Koreans practitioners travelling to China to study under the venerable Mazu (709-788). These pioneers had started a trend: over the next century, numerous Korean pupils studied under Mazu's successors, and some of them returned to Korea and established the Nine Mountain Schools. This was the beginning of Korean Zen (Seon). Among the most notable Seon masters were Jinul (1158-1210), who established a reform movement and introduced koan practice to Korea, and Taego Bou (1301-1382), who studied the Linji tradition in China and returned to unite the Nine Mountain Schools. In modern Korea, the largest Buddhist denomination is the Jogye Order, a Zen sect named after Huineng (the famed sixth Zen patriarch).

Zen in Japan

Although the Japanese had known of China's Chan Buddhism for centuries, it was not introduced as a separate school until the 12th century, when Myōan Eisai travelled to China and returned to establish a Linji lineage, which is known in Japan as Rinzai. Decades later, Nanpo Jomyo (南浦紹明) also studied Linji teachings in China before founding the Japanese Otokan lineage, the most influential branch of Rinzai. In 1215, Dogen, a younger contemporary of Eisai's, journeyed to China himself, where he became a disciple of the Caodong master Tiantong Rujing. After his return, Dogen established the Soto school, the Japanese branch of Caodong. Over time, Rinzai came to be divided into several subschools, including Myoshin-ji, Nanzen-ji, Tenryū-ji, Daitoku-ji, and Tofuku-ji.

These sects represented the entirety of Zen in Japan until Ingen, a Chinese monk, founded the Obaku school in the 17th century. Ingen had been a member of the Linji school, the Chinese equivalent of Rinzai, which had developed separately from the Japanese branch for hundreds of years. Thus, when Ingen journeyed to Japan following the fall of the Ming Dynasty, his teachings were seen as representing a distinct and separate school. The Obaku school was named for Mount Obaku (Chinese: Huangboshan), which had been Ingen's home in China.

The three schools introduced above (Soto (曹洞), Rinzai (臨済), and Obaku (黃檗)) have all survived to the present day and are still active in the Japanese religious community. Of them, Soto is the largest and Obaku the smallest.

Zen Doctrine

Zen, as a Mahayana school, expounds classical Buddhist formulations, but extends them with later doctrinal and praxical developments. As such, they teach the fundamental (and foundational) elements of Buddhist philosophy, including the Four Noble Truths, the Eightfold Path, the doctrine of dependent origination (pratitya samutpada), the fivefold ethical schema, and the three metaphysical truths (or dharma seals: non-self, impermanence, and dukkha). In addition, Zen philosophy also includes numerous teachings specific to Mahayana Buddhism, including the Mahayana conception of the paramitas and the ideal of the bodhisattva's universal salvific power. Further, Mahayana Buddhist religious figures such as Kuan Yin, Mañjuśri, Samantabhadra, and Amitabha Buddha are venerated in Zen temples along with Śakyamuni Buddha, although Amitabha takes a less prominent role than in many other forms of Mahayana. This is particularly true in the Japanese Soto and Rinzai schools, which conceive of themselves as purer Zen schools that are, resultantly, less influenced by other Buddhist sects.

Philosophically, Zen Buddhist schools (of all stripes) can be seen as the intellectual successors of the Madhyamaka sect of Indian Buddhism, in that they both stress that all phenomenal experience is ultimately void (sunyata) (empty of enduring reality). The intellectual and experiential understanding of this metaphysical truth is seen as one of the keys to enlightenment (satori (discussed below)).

Praxis Orientation

Zen is not primarily an intellectual philosophy nor is it a solitary pursuit. Zen temples emphasize meticulous daily practice, and hold intensive monthly meditation retreats. Practicing with others is valued as a means of avoiding the snares of ego. In explaining the Zen Buddhist path to Westerners, Japanese Zen teachers have frequently made the point that Zen is a "way of life" and not solely a state of consciousness. Demonstrating this, D.T. Suzuki suggested that the Zen lifestyle implies five related commitments: to humility, to labor, to service, to prayer and gratitude, and to meditation.

An aspect of this praxis focus is the Zen school's distrust of textual (and intellectual) knowledge, as they feel that such inherently contingent "knowing" is innately inferior to the experiential truths obtained through meditation.

Textual Basis

The Zen tradition draws primarily on Mahāyāna sutras composed in India and China, particularly the Heart Sutra; the Diamond Sutra; the Lankavatara Sutra; the Samantamukha Parivarta (a chapter of the Lotus Sutra); and the Platform Sutra of Huineng. Their canon of literature also contains the recorded and codified teachings of various past Zen masters.

Zen Praxis

Zen in Daily Life

Given the stress upon the practicality of Zen, it is perhaps unsurprising that Zen monks have always taken part in the day-to-day affairs of their monastic dwellings, including gardening, farming, carpentry, architecture, housekeeping, administration, and the practice of folk medicine. D. T. Suzuki explains this variation by noting the differences between the lifestyles of Indian Buddhists and their East Asian counterparts (in China, Japan, Vietnam and Korea). Since East Asian culture lacked the support for mendicancy relied upon by Indian Buddhists, social circumstances required that the abbot and the monks all work together to keep up their temples, training-centers and monasteries, which, in turn, required Zen to be commensurable with such a lifestyle.

Zazen

The core of Zen practice, sitting meditation, is called zazen (坐禅). During zazen, practitioners usually assume a sitting position such as the lotus, half-lotus, Burmese, or seiza postures. Awareness is directed towards one's posture and breathing. Often, a square or round cushion (zafu) placed on a padded mat (zabuton) is used to sit on; in some cases, a chair may be used. Some small sectarian variations exist in certain practical matters: for example, in Rinzai Zen, practitioners typically sit facing the center of the room, while Soto practitioners traditionally sit facing a wall. Further, Soto Zen practice centers around shikantaza meditation ("just-sitting"), which is meditation with no objects, anchors, or content.[4] Conversely, Rinzai Zen emphasizes attention to the breath and koan practice.

The amount of time each practitioner spends in zazen varies. The generally acknowledged key, however, is daily regularity, as Zen teaches that the ego will naturally resist (especially during the initial stages of practice). Practicing Zen monks may perform four to six periods of zazen during a normal day, with each period lasting 30 to 40 minutes. Normally, a monastery will hold a monthly retreat period (sesshin), lasting between one and seven days. During this time, zazen is practiced more intensively: monks may spend four to eight hours in meditation each day, sometimes supplemented by further rounds of zazen late at night. Even householders are urged to spend at least five minutes per day in conscious and uninterupted meditation.

Dogen's teacher Rujing was said to sleep fewer than four hours each night, spending the balance in zazen[5].

The teacher

Because the Zen tradition emphasizes direct communication over scriptural study, the role of the Zen teacher has traditionally been central. Generally speaking, a Zen teacher is a person ordained in any tradition of Zen to teach the dharma, guide students of meditation, and perform rituals.

An important concept for all Zen sects in East Asia is the notion of Dharma transmission, the claim of a line of authority that goes back to the Buddha via the teachings of each successive master to each successive student. This concept relates to Bodhidharma`s original depiction of Zen:

- A special transmission outside the scriptures; (教外別傳)

- No dependence upon words and letters; (不立文字)

- Direct pointing to the human mind; (直指人心)

- Seeing into one's own nature and attaining Buddhahood. (見性成佛)[6]

As a result of this understanding, claims of Dharma transmission have been normative aspects of all Zen sects. John McRae’s study “Seeing Through Zen” explores this assertion of lineage as a distinctive and central aspect of Zen Buddhism. He writes of this “genealogical” approach so central to Zen’s self-understanding, that while not without precedent, has unique features. It is “relational (involving interaction between individuals rather than being based solely on individual effort), generational (in that it is organized according to parent-child, or rather teacher-student, generations) and reiterative (i.e., intended for emulation and repetition in the lives of present and future teachers and students.”

McRae offers a detailed criticism of lineage, but he also notes it is central to Zen. So much so that it is hard to envision any claim to Zen that discards claims of lineage. Therefore, for example, in Japanese Soto lineage charts become a central part of the Sanmatsu, the documents of Dharma transmission. And it is common for daily chanting in Zen temples and monasteries to include the lineage of the school, in whole or in part, reciting the names of all dharma ancestors and teachers that have transmitted Zen teaching.

In Japan during the Tokugawa period (1600–1868), some came to question the lineage system and its legitimacy. The Zen master Dokuan Genko (1630–1698), for example, openly questioned the necessity of written acknowledgement from a teacher, which he dismissed as "paper Zen." The only genuine transmission, he insisted, was the individual's independent experience of Zen enlightenment, an intuitive experience that needs no external confirmation. An occasional teacher in Japan during the Tokugawa period did not adhere to the lineage system; these were termed mushi dokugo (無師獨悟, "independently enlightened without a teacher") or jigo jisho (自悟自証, "self-enlightened and self-certified"). They were generally dismissed and perhaps of necessity leave no independent transmission. Nevertheless, modern Zen Buddhists also consider questions about the dynamics of the lineage system, inspired in part by academic research into the history of Zen.

Honorific titles associated with teachers typically include, in Chinese, Fashi (法師) or Chanshi (禪師); in Korean, Sunim or Seon Sa (선사); in Japanese, Osho (和尚), Roshi (老師), or Sensei (先生); and in Vietnamese, Thầy. Note that many of these titles are not specific to Zen but are used generally for Buddhist priests; some, such as sensei are not even specific to Buddhism.

The English term Zen master is often used to refer to important teachers, especially ancient and medieval ones. However, there is no specific criterion by which one may be called a Zen master. The term is less common in reference to modern teachers.

Koan practice

Some Zen Buddhists practice meditation on koans during zazen. A koan (literally "public case") is a story or dialog, generally related to Zen or other Buddhist history; the most typical form is an anecdote involving early Chinese Zen masters. Koan practice is particularly emphasized by the Japanese Rinzai schools, but it also occurs in other forms of Zen.

According to one view, a koan embodies a realized principle, or law of reality. Koans often appear paradoxical or linguistically meaningless dialogs or questions. The 'answer' to the koan involves a transformation of perspective or consciousness, which may be either radical or subtle, possibly akin to the experience of metanoia in Christianity. They are a tool to allow the student to approach enlightenment by essentially 'short-circuiting' the logical way we order the world. In order to try to answer these often unanswerable problems, the thinker may be forced to create new mental pathways. Those pathways then may be useful for other problems, thus producing a "mind expansion" effect.

The Zen student's mastery of a given koan is presented to the teacher in a private interview, referred to as dokusan (独参), daisan (代参), or sanzen (参禅). Zen teachers advise that the problem posed by a koan is to be taken quite seriously, and to be approached as literally a matter of life and death. Koans do not have "no answer". There is a sharp distinction between right and wrong ways of answering a koan—although there may be many "right answers", practitioners are expected to demonstrate their understanding of the koan and of Zen through their answers.

While there is no single correct answer for any given koan, there are compilations of accepted answers to koans that serve as references for teachers. These collections are of great value to modern scholarship on the subject.

Zen in the Modern World

Japan

Some contemporary Japanese Zen teachers, such as Daiun Harada and Shunryu Suzuki, have criticized Japanese Zen as being a formalized system of empty rituals in which very few Zen practitioners ever actually attain realization. They assert that almost all Japanese temples have become family businesses handed down from father to son, and the Zen priest's function has largely been reduced to officiating at funerals.

The Japanese Zen establishment—including the Soto sect, the major branches of Rinzai, and several renowned teachers— has been criticized for its involvement in Japanese militarism and nationalism during World War II and the preceding period. A notable work on this subject was Zen at War (1998) by Brian Victoria, an American-born Soto priest. This openness has allowed non-Buddhists to practice Zen, especially outside of Asia, and even for the curious phenomenon of an emerging Christian Zen lineage, as well as one or two lines that call themselves "nonsectarian." With no official governing body, it's perhaps impossible to declare any authentic lineage "heretical." Some schools emphasize lineage and trace their line of teachers back to Japan, Korea, Vietnam or China; other schools do not.

Zen in the Western world

Although it is difficult to trace when the West first became aware of Zen as a distinct form of Buddhism, the visit of Soyen Shaku, a Japanese Zen monk, to Chicago during the World Parliament of Religions in 1893 is often pointed to as an event that enhanced its profile in the Western world. It was during the late 1950s and the early 1960s that the number of Westerners, other than the descendants of Asian immigrants, pursuing a serious interest in Zen reached a significant level.

Zen and Western culture

In Europe, the Expressionist and Dada movements in art tend to have much in common thematically with the study of koans and actual Zen. The early French surrealist René Daumal translated D.T. Suzuki as well as Sanskrit Buddhist texts.

Eugen Herrigel's book Zen in the Art of Archery (1953)[7], describing his training in the Zen-influenced martial art of Kyudo, inspired many of the Western world's early Zen practitioners. However, many scholars are quick to criticize this book.

The British-American philosopher Alan Watts took a close interest in Zen Buddhism and wrote and lectured extensively on it during the 1950s. He understood it as a vehicle for a mystical transformation of consciousness, and also as a historical example of a non-Western, non-Christian way of life that had fostered both the practical and fine arts.

The Dharma Bums, a novel written by Jack Kerouac and published in 1959, gave its readers a look at how a fascination with Buddhism and Zen was being absorbed into the bohemian lifestyles of a small group of American youths, primarily on the West Coast. Beside the narrator, the main character in this novel was "Japhy Ryder", a thinly-veiled depiction of Gary Snyder. The story was based on actual events taking place while Snyder prepared, in California, for the formal Zen studies that he would pursue in Japanese monasteries between 1956 and 1968.

Thomas Merton (1915–1968) the Trappist monk and priest [1] was internationally recognized as having one of those rare Western minds which was entirely at home in Asian experience. Like his friend, the late D.T. Suzuki, Merton believed that there must be a little of Zen in all authentic creative and spriritual experience. The dialogue between Merton and Suzuki (Wisdom in Emptiness" in: Zen and the Birds of Appetite, 1968) explores the many congruencies of Christian mysticism and Zen. (Main publications: The Way of Chuang Tzu, 1965; Mystics and Zen Masters, 1967; Zen and the Birds of Appetite, 1968).

While Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, by Robert M. Pirsig, was a 1974 bestseller, it in fact has little to do with Zen per se. Rather it deals with the notion of the metaphysics of "quality" from the point of view of the main character. Pirsig was attending the Minnesota Zen Center at the time of writing the book[2]. He has stated that, despite its title, the book "should in no way be associated with that great body of factual information relating to orthodox Zen Buddhist practice".

Western Zen lineages

Over the last fifty years, mainstream forms of Zen, led by teachers who trained in East Asia and by their successors, have begun to take root in the West. In North America, the Zen lineages derived from the Japanese Soto school are the most numerous type. Among these are the lineage of the San Francisco Zen Center, established by Shunryu Suzuki; the White Plum Asanga, founded by Hakuyu Taizan Maezumi; Big Mind founded by Dennis Genpo Merzel; the Ordinary Mind school, founded by Joko Beck, one of Maezumi's heirs; and the Katagiri lineage, founded by Dainin Katagiri, which has a significant presence in the Midwest. Note that both Taizan Maezumi and Dainin Katagiri served as priests at Zenshuji Soto Mission in the 1960's.

Taisen Deshimaru, a student of Kodo Sawaki, was a Soto Zen priest from Japan who taught in France. The International Zen Association, which he founded, remains influential. The American Zen Association, headquartered at the New Orleans Zen Temple, is one of the North American organizations practicing in the Deshimaru tradition.

The Sanbo Kyodan is a Japan-based reformist Zen group, founded in 1954 by Yasutani Hakuun, which has had a significant influence on Zen in the West. Sanbo Kyodan Zen is based primarily on the Soto tradition, but also incorporates Rinzai-style koan practice. Yasutani's approach to Zen first became prominent in the English-speaking world through Philip Kapleau's book The Three Pillars of Zen (1965), which was one of the first books to introduce Western audiences to Zen as a practice rather than simply a philosophy. Among the Zen groups in North America, Hawaii, Europe, and New Zealand which derive from Sanbo Kyodan are those associated with Kapleau, Robert Aitken, and John Tarrant.

There are also a number of Rinzai Zen centers in the West, such as the Rinzaiji lineage of Kyozan Joshu Sasaki and the Dai Bosatsu lineage established by Eido Shimano.

Not all the successful Zen teachers in the West have been from Japanese traditions. There have also been teachers of Chan, Seon, and Thien Buddhism.

The first Chinese Buddhist priest to teach Westerners in North America was Hsuan Hua, who taught Zen, Chinese Pure Land, Tiantai, Vinaya, and Vajrayana Buddhism in San Francisco during the early 1960s. He went on to found the City Of Ten Thousand Buddhas, a monastery and retreat center located on a 237 acre (959,000 m²) property near Ukiah, California. Another Chinese Zen teacher with a Western following is Sheng-yen, a master trained in both the Caodong and Linji schools (equivalent to the Japanese Soto and Rinzai, respectively). He first visited the United States in 1978 under the sponsorship of the Buddhist Association of the United States, and, in 1980, founded the Ch’an Mediation Society in Queens, New York.[3].

The most prominent Korean Zen teacher in the West was Seung Sahn. Seung Sahn founded the Providence Zen Center in Providence, Rhode Island; this was to become the headquarters of the Kwan Um School of Zen, a large international network of affiliated Zen centers.

Two notable Vietnamese Zen teachers have been influential in Western countries: Thich Thien-An and Thich Nhat Hanh. Thich Thien-An came to America in 1966 as a visiting professor at UCLA and taught traditional Thien meditation. Thich Nhat Hanh was a monk in Vietnam during the Vietnam War, during which he was a peace activist. In response to these activities, he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1967 by Martin Luther King, Jr. In 1966, he left Vietnam in exile and now resides at Plum Village, a monastery in France. He has written more than one hundred books about Buddhism, which have made him one of the very few most prominent Buddhist authors among the general readership in the West. In his books and talks, Thich Nhat Hanh emphasizes mindfulness (sati) as the most important practice in daily life.

Pan-lineage organizations

In the United States, two pan-lineage organizations have formed in the last few years. The oldest is the American Zen Teachers Association which sponsors an annual conference. North American Soto teachers in North America, led by several of the heirs of Taizan Maezumi and Shunryu Suzuki, have also formed a Soto Zen Buddhist Association.

Notes

- ↑ The earlier date is from the (near) contemporary text The Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks (645), while the later is found in the Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall (952). Both of these accounts can be found in Jeffrey Broughton's The Bodhidharma Anthology: The Earliest Records of Zen (University of California Press, 1999).

- ↑ For more on the history and development of the koan, see Miura and Sasaki

- ↑ This section contains some text from the Wikipedia article on "Chan", available under the GNUFDL license: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Chan&oldid=89063409

- ↑ Considerable textual, philosophical, and phenomenological justification for this practice can be found in Dogen's Shobogenzo.

- ↑ Dogen's formative years in China by Takashi James Kodera ISBN 0-7100-0212-2

- ↑ Welter, Albert. The Disputed Place of "A Special Transmission" Outside the Scriptures in Ch'an (in English). Retrieved 2006-06-23.

- ↑ Zen in the Art of Archery, (ISBN 0-375-70509-0)

Bibliography

- Hogi, Victor Sogen, Zen Dust

- Miura & Sasaki, Zen Koan

- An Introduction to Zen Buddhism by D.T. Suzuki

- Japanese Zen Buddhist Philosophy in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Zen Guide: Comprehensive Guide to Zen and Buddhism Principles, Practice Guides, Active Discussion Forum, Organization Directory, full text of key Sutras and other books.

- Zen Buddhism WWW Virtual Library

- The Japanese Journal of Religious Studies has a number of papers related to Zen

- The International Research Institute for Zen Buddhism

- Zen texts

- Sotozen-net

- Digital Dictionary of Buddhism

- Zen Centers at the Open Directory Project

- TheZenSite.com

- http://www.onedropzendo.org/ Zen Master Shodo Harada Roshi, and One Drop Zendo, a worldwide Zen Buddhist community

- Rinnou.net

- E-Sangha Zen Buddhism Forum

- A Compilation of Zen Stories and the Westerners' reactions to them

- (French)Zen and Buddhism in Switzerland

- [4] Zen Holy War? A book review by Josh Baran

- Official Site of Master Tae Hye sunim Zen Community

- Taiwan Zen Buddhist Association

- American Zen Association

- Daily zen text from both the modern and the ancient

- Wei, Wei Wu,"Why Lazarus Laughed: The Essential Doctrine Zen-Advaita-Tantra", Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd., London, 1960. [5]

- http://www.lastelladelmattino.org/cristiano/index.php/the-morning-star/ Site of the italian community of dialogue between Zen and Gospel (All the site pages have got an English and French translation with a rough machine translation)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.