Brandt, Willy

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (15 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Copyedited}}{{approved}}{{images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}} |

| + | {{epname|Brandt, Willy}} | ||

| + | [[image:Willy_Brandt-01.png|thumb|right|160px|'''Willy Brandt''' in 1973]] | ||

| + | '''Willy Brandt''', born '''Herbert Ernst Karl Frahm''' (December 18, 1913 – October 8, 1992), was a [[Germany|German]] [[politics|politician]], chancellor of [[West Germany]] (1969–1974) and leader of the [[Social Democratic Party of Germany]] (SPD) (1964–1987). Because resistance from the opposition kept much of Brandt's domestic program from being implemented, his most important legacy is the ''Ostpolitik'', a policy aimed at improving relations with [[East Germany]], [[Poland]], and the [[Soviet Union]]. This policy caused considerable controversy in West Germany, but won Brandt the [[Nobel_Peace_Prize#Nobel_Prize_in_Peace|Nobel Peace Prize]] in 1971. The citation stated that "the ideal of peace" had been a "guiding star" to the chancellor throughout his active political career."<ref>The Nobel Foundation (1971), [http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/1971/press.html: The 1971 Nobel Peace Prize - Presentation Speech,] Nobelprize.org. Retrieved June 26, 2007.</ref> | ||

| − | [[ | + | Brandt was forced to resign as chancellor in 1974 after it became known that one of his closest aides had been working for the East German secret service (Stasi). This became one of the biggest political scandals in postwar West German history. In retirement, he chaired the Brandt Commission, an independent enquiry into how to reduce the North-South divide, conserve the environment and build a world "in which sharing, justice and peace" prevails. The subsequent report, "North-South: A Program for Survival" published in 1980 anticipated many and materially contributed toward the goal enshrined in the [[United Nations]]' Millennium Development Goals<ref>James Bernard Quilligan, [http://www.brandt21forum.info/Report_Introduction.htm The Brandt Equation: 21st Century Blueprint for the New Global Economy], Centre for Global Negotiations. Retrieved June 16, 2007.</ref> |

| − | + | Even though his period as chancellor ended in controversy, Brandt continued to use his intellect and his passion for peace and justice to promote debate about North-South equity, making a very valuable and enduring contribution to thinking about development, economics and third-world debt. His commission enabled several distinguished out-of-office politicians, such as [[Edward Heath]], to contribute from their experience to some of the most important issues of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries and how to ensure planetary survival. | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Because he had escaped from [[Nazism|Nazi]] Germany and had no association with the Third Reich, Brandt was well placed to lead Germany's reconstruction as a economic power with a largely pacifist ethos and a willingness to submerge its national identity into a European one.<ref>Nile Gardiner, [http://www.heritage.org/Research/Europe/wm1157.cfm "President Bush in Europe: Shaping US Policy toward Germany,"] Heritage.org (July 26, 2006). Retrieved June 16, 2007.</ref> German reunification in 1990 owed much to Brandt’s policy of rapprochement with the East. | ||

| − | Brandt was | + | == Early life and World War II== |

| + | Brandt was born '''Herbert Ernst Karl Frahm''' in Lübeck, [[Germany]] to Martha Frahm, an unwed mother who worked as a cashier for a department store. His father was an accountant from Hamburg by the name of John Möller, whom Brandt never met. | ||

| + | He became an apprentice at the shipbroker and ship's agent F. H. Bertling. He joined the "Socialist Youth" in 1929 and the [[Social Democratic Party of Germany|Social Democratic Party]] (SPD) in 1930. He left the SPD to join the more left wing [[SAPD|Socialist Workers Party]] (SAPD), which was allied to the [[Workers' Party of Marxist Unification|POUM]] in Spain and the [[Independent Labour Party|ILP]] in Britain. In 1933, using his connections with the port and its ships from the time he had been apprentice, he left Germany for [[Norway]] on a ship to escape [[Nazism|Nazi]] persecution. It was at this time that he adopted the pseudonym '''Willy Brandt''' to avoid detection by Nazi agents. In 1934, he took part in the founding of the International Bureau of Revolutionary Youth Organizations, and was elected to its secretariat. | ||

| − | + | Brandt visited Germany from September to December 1936, disguised as a Norwegian student named Gunnar Gaasland. In 1937, during the [[Spanish Civil War|Civil War]], he worked in [[Spain]] as a journalist. In 1938, the German government revoked his citizenship, so he applied for Norwegian citizenship. In 1940, he was arrested in Norway by occupying German forces, but he was not identified because he wore a Norwegian uniform. On his release, he escaped to neutral [[Sweden]]. In August 1940, he became a Norwegian citizen, receiving his passport from the Norwegian embassy in [[Stockholm]], where he lived until the end of the war. Brandt returned to Sweden to lecture on December 1, 1940, at Bommersvik College about the problems experienced by the social democrats in Nazi Germany and the occupied countries at the start of [[World War II]]. | |

| − | + | == Mayor of West Berlin, foreign minister of West Germany == | |

| − | + | [[Image:John F. Kennedy meeting with Willy Brandt, March 13, 1961.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Brandt with President [[John F. Kennedy]], March 1961]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == Mayor of West Berlin, | ||

| − | [[Image:John F. Kennedy meeting with Willy Brandt, March 13, 1961.jpg|thumb|right|Brandt with President [[John F. Kennedy]], March 1961 | ||

In late 1946, Brandt returned to Berlin, working for the Norwegian government. | In late 1946, Brandt returned to Berlin, working for the Norwegian government. | ||

In 1948, he joined the [[Social Democratic Party of Germany]] (SPD) in Berlin. He became a German citizen again and formally adopted his pseudonym as his legal name. | In 1948, he joined the [[Social Democratic Party of Germany]] (SPD) in Berlin. He became a German citizen again and formally adopted his pseudonym as his legal name. | ||

| − | Outspoken against the Soviet repression of the [[1956 Hungarian Revolution]] and against [[Nikita Khrushchev|Khrushchev's]] 1958 proposal that Berlin receive the status of a "free city" | + | Outspoken against the [[Soviet Union|Soviet]] repression of the [[Hungarian_Revolution_of_1956|1956 Hungarian Revolution]] and against [[Nikita Khrushchev|Khrushchev's]] 1958 proposal that Berlin receive the status of a "free city," he was considered to belong to the right wing of his party, an assessment that would later change. |

| − | Brandt was supported by the powerful publisher [[Axel Springer]]. From October 3 1957 to 1966, he was | + | Brandt was supported by the powerful publisher [[Axel Springer]]. From October 3, 1957 to 1966, he was mayor of [[West Berlin]], a particularly stressful time for the city with the construction of the [[Berlin Wall]]. |

Brandt became chairman of the SPD in 1964, a post he retained until 1987. | Brandt became chairman of the SPD in 1964, a post he retained until 1987. | ||

| − | Brandt was the SPD candidate for | + | Brandt was the SPD candidate for chancellor in 1961, but lost to [[Konrad Adenauer]]'s conservative [[Christian Democratic Union (Germany)|Christian Democratic Union (CDU)]]. In 1965, he ran again, and lost to the popular [[Ludwig Erhard]]. But Erhard's government was short-lived, and, in 1966, a grand coalition between the SPD and CDU was formed; Brandt became foreign minister and vice chancellor. |

== Chancellor of West Germany == | == Chancellor of West Germany == | ||

| − | After the elections of 1969, again with Brandt as lead candidate, the SPD became stronger and after three weeks of negotiation formed a coalition government with the small liberal [[Free Democratic Party of Germany]] (FDP). Brandt was elected | + | After the elections of 1969, again with Brandt as lead candidate, the SPD became stronger and after three weeks of negotiation formed a coalition government with the small liberal [[Free Democratic Party of Germany]] (FDP). Brandt was elected chancellor. |

== Foreign policy == | == Foreign policy == | ||

| − | + | As chancellor, Brandt gained more scope to develop his ''[[Ostpolitik]]''. He was active in creating a degree of rapprochement with [[East Germany]] and in improving relations with the [[Soviet Union]], [[Poland]] and other [[Eastern Bloc]] countries. | |

| − | |||

| − | As chancellor, Brandt gained more scope to develop his ''[[Ostpolitik]]''. He was active in creating a degree of rapprochement with [[East Germany]] and in improving relations with the [[Soviet Union]], [[Poland]] and other [[Eastern Bloc]] countries. | ||

| − | A seminal moment came in December 1970 with the famous ''[[Warschauer Kniefall]]'' in which Brandt, apparently spontaneously, knelt down at the monument to victims of [[Warsaw Ghetto Uprising]]. The uprising occurred during the military occupation of Poland and the monument is to those killed by German troops who suppressed the uprising and deported remaining ghetto residents to concentration camps. | + | A seminal moment came in December 1970 with the famous ''[[Warschauer Kniefall]]'' in which Brandt, apparently spontaneously, knelt down at the monument to victims of [[Warsaw Ghetto Uprising]]. The uprising occurred during the military occupation of Poland and the monument is to those killed by German troops who suppressed the uprising and deported remaining ghetto residents to concentration camps. |

| − | Brandt was named [[TIME]] magazine's [[Person of the Year|Man of the Year]] for 1970. | + | Brandt was named ''[[Time (magazine)|TIME]]'' magazine's “[[Person of the Year|Man of the Year]]” for 1970. |

| − | In 1971 | + | In 1971 Brandt received the [[Nobel_Peace_Prize#Nobel_Prize_in_Peace|Nobel Peace Prize]] for his work in improving relations with East Germany, Poland and the Soviet Union. In his Nobel Lecture, Brandt referred to the current conflict between [[India]] and [[Pakistan]] suggesting that what he had been able to achieve was "little enough" in the face if this new war. He continued: |

| − | + | <blockquote>War must not be a means to achieve political ends. Wars must be eliminated, not merely limited. No national interest can today be isolated from collective responsibility for peace. This fact must be recognized in all foreign relations. As a means of achieving European and worldwide security, therefore, foreign policy must aim to reduce tensions and promote communication beyond frontiers.<ref>Willy Brandt, [http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/1971/brandt-lecture-e.html "Nobel Lecture"], Nobelprize.org. Retrieved June 16, 2007.</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | + | [[Image:Willy-brandt-und-richard-nixon 1-588x398.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Willy Brandt and [[Richard Nixon]], December 29, 1971]] | |

| − | In West Germany, Brandt's Ostpolitik was extremely controversial, dividing the populace into two camps: one side, most notably the victims of Stalinist ethnic cleansing from | + | In West Germany, Brandt's ''Ostpolitik'' was extremely controversial, dividing the populace into two camps: one side, most notably the victims of [[Josef Stalin|Stalinist]] ethnic cleansing from historical Eastern Germany and Eastern Europe, loudly voiced their opposition, calling the policy "illegal" and "high treason," while others applauded Brandt's move as aiming at "Wandel durch Annäherung" ("change through [[rapprochement]]," i.e., encouraging change through a policy of engagement rather than isolation). Supporters of Brandt claim his ''Ostpolitik'' did help to break down the Eastern Bloc's siege mentality and increase the awareness of the contradictions in their brand of [[socialism]], which—together with other events—eventually led to its downfall. ''Ostpolitik'' was strongly opposed by the conservative parties and many social democrats as well. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Domestic policies == | == Domestic policies == | ||

| + | === Political and social changes of the 1960s === | ||

| − | + | West Germany in the late 1960s was shaken by student disturbances and a general 'change of the times' that not all Germans were willing to accept or approve. What had seemed a stable, peaceful nation, happy with its outcome of the "Wirtschaftswunder" ("economic miracle") turned out to be a deeply conservative, bourgeois, and insecure people with a lot of citizens unable to face their Nazi past. The younger generation, mostly students, took a very progressive stance toward Germany’s future and were a powerful voice against a way of life that they considered outdated and old-fashioned. | |

| − | + | === Brandt wins over the students === | |

| − | + | Brandt's predecessor, [[Kurt Georg Kiesinger]], had been a member of the [[Nazism|Nazi]] party. Brandt had been a victim of Nazi terror; no wider a gap could have existed between the two chancellors. Unlike Brandt, Kiesinger was unable to understand the students' political demands. For him, they were nothing but "a shameful crowd of long-haired drop-outs who needed a bath and someone to discipline them." The students (with a sizeable number of intellectuals backing them up) turned their parents' values and virtues upside down and questioned the West German society in general, seeking social, legal and political reforms. | |

| − | + | On the domestic field, Brandt pursued exactly this—a course of social, legal and political reforms. In his first parliament speech after his election, Brandt signaled that he had comprehended what made the students go out and demonstrate against authority. In the speech he claimed his political course of reforms ending it with the famous summarizing words "Wir wollen mehr Demokratie wagen" ("Let's dare more democracy"). This made him—and the SPD, too—extremely popular among most students and other young West Germans who dreamed of a country quite different from the one their parents had built after the war. However, many of Brandt's reforms met the resistance of state governments (dominated by CDU/CSU). The spirit of reformist optimism was cut short by the [[1973 Oil Crisis]]. Brandt's domestic policy has been criticized of having caused many of West Germany's economic problems. | |

=== Crisis in 1972 === | === Crisis in 1972 === | ||

| − | Because of these controversies, several members of his coalition switched sides. In May 1972, the opposition CDU believed it had the majority in the Bundestag and demanded a vote on a | + | Because of these controversies, several members of his coalition switched sides. In May 1972, the opposition CDU believed it had the majority in the Bundestag (German parliament) and demanded a vote on a motion of no confidence (''Misstrauensvotum''). Had this motion passed, Rainer Barzel would have replaced Brandt as chancellor. To everyone's surprise, the motion failed. The margin was extremely narrow (two votes) and much later it was revealed that one or perhaps two members of the CDU had been paid off by the Stasi of [[East Germany]] to vote for Brandt. |

| − | Though Brandt | + | Though Brandt remained chancellor, he had lost his majority. Subsequent initiatives in the Bundestag, most notably on the budget, failed. Because of this stalemate, the Bundestag was dissolved and new elections were called. Brandt's ''Ostpolitik'', as well as his reformist domestic policies, were popular with parts of the young generation and led his SPD party to its best-ever federal election result in late 1972. |

| − | During the 1972 campaign, many popular West German artists, intellectuals, writers, actors and professors supported Brandt and the SPD. Among them were Günter Grass, Walter Jens, and even the football (soccer) player Paul Breitner. Public endorsements of the SPD via advertisements and, more recently, internet pages have become a widespread phenomenon since then. | + | During the 1972 campaign, many popular West German artists, intellectuals, writers, actors and professors supported Brandt and the SPD. Among them were [[Günter Grass]], Walter Jens, and even the football (soccer) player Paul Breitner. Public endorsements of the SPD via [[advertising|advertisements]]—and, more recently, internet pages—have become a widespread phenomenon since then. |

| − | To counter any notions about being sympathetic to | + | To counter any notions about being sympathetic to [[communism]] or soft on left-wing extremists, Brandt implemented tough legislation that barred "radicals" from public service ("Radikalenerlass"). |

== The Guillaume affair and Brandt's resignation == | == The Guillaume affair and Brandt's resignation == | ||

| − | Around 1973, West German security organizations received information that one of Brandt's personal assistants, Günter Guillaume, was a spy for | + | Around 1973, West German security organizations received information that one of Brandt's personal assistants, Günter Guillaume, was a [[spy]] for East Germany. Brandt was asked to continue work as usual, and he agreed, even taking a private vacation with Guillaume. Guillaume was arrested on April 24, 1974, and the West German government blamed Brandt for having a spy in his party. At the same time, some revelations about Brandt's private life (he had had some short-lived affairs with prostitutes) appeared in newspapers. Brandt contemplated [[suicide]] and even drafted a suicide note. He chose instead to accept responsibility for Guillaume, and resigned on May 7, 1974. |

| − | Guillaume had been a spy for [[East Germany]], supervised by Markus Wolf, head of the Main Intelligence Administration of the East German Ministry for State Security. | + | Guillaume had been a spy for [[East Germany]], supervised by Markus Wolf, head of the Main Intelligence Administration of the East German Ministry for State Security. Wolf stated after the reunification that the resignation of Brandt had never been intended, and that the affair had been one of the biggest mistakes of the East German secret service. This was led 1957-1989 by [[Erich Mielke]], an old follower of Stalin and Beria. |

| − | Brandt was succeeded as | + | Brandt was succeeded as chancellor by the Social Democrat [[Helmut Schmidt]], who, unlike Brandt, belonged to the right wing of his party. For the rest of his life, Brandt remained suspicious that his fellow social democrat and longtime rival Herbert Wehner had been scheming for his downfall, but evidence for this seems scant. |

| − | The story of Brandt and Guillaume is told in the play | + | The story of Brandt and Guillaume is told in the play ''Democracy'' by Michael Frayn. The play follows Brandt's career from his election as the first left-of-center chancellor in West Germany in 40 years to his downfall at the hands of his trusted assistant Guillaume. The play examines Guillaume's dual identity as trusted personal assistant to the West German chancellor and Stasi spy, and Guillaume's conflict as his duty to Brandt's enemies clashes with his genuine love and admiration for the chancellor. |

== Later life == | == Later life == | ||

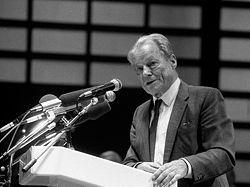

| + | [[Image:Willy Brandt.jpg|thumb|250px|Willy Brandt speaking in Dortmund, 1987]] | ||

| + | After his term as chancellor, Brandt remained head of his party, the SPD, until 1987 and retained his seat in the Bundestag. Brandt was head of the Socialist International from 1976 to 1992, which he called a world party of peace, working to enlarge that organization beyond the borders of Europe. In 1977, he was appointed chair of the Independent Commission for International Developmental Issues, which produced a report, in 1980, calling for drastic changes in the world's attitude to development in the Third World. This became known as the [[Brandt Report]]. | ||

| − | + | His continued interest in development issues are indicated by the title of his 1986 book, which links arms with hunger while the Centre for Global Negotiations has developed from his work, which is dedicated to promoting a global Marshall Plan type initiative. The Centre also has links with the Network of Spiritual Progressives, a project of the Tikkun community. ''Tikkun'' is the Hebrew phrase for "repairing," as in ''tikkun olam'' (to repair the world).<ref>[http://www.spiritualprogressives.org/article.php?story=20070226095019665 What is the Global Marshall Plan?] The Network of Spiritual Progressives. Retrieved June 16, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | In 1975, it was widely feared that [[Portugal]] would fall to | + | In 1975, it was widely feared that [[Portugal]] would fall to communism; Brandt supported the Democratic Socialist Party of Mário Soares that won a major victory, thus keeping Portugal capitalist. He also supported Felipe González's newly legal socialist party in [[Spain]] after [[Francisco Franco|Franco]]'s death. |

| − | In | + | In late 1989, Brandt became one of the first leftist leaders in West Germany to publicly favor [[German reunification|reunification]] over some sort of two-state federation. His public statement "Now grows together what belongs together" was quoted frequently. |

| − | + | One of Brandt's last public appearances was flying to [[Baghdad]], to free some Western hostages held by [[Saddam Hussein]], after the invasion of [[Kuwait]] in 1990. He died of colon [[cancer]] at his home in Unkel, a town on the [[Rhine]], and was given the first German state funeral since 1929. He was buried at the cemetery at Zehlendorf in [[Berlin]]. | |

| − | + | Brandt was a member of the [[European Parliament]] from 1979 to 1983, and Honorary Chairman of the SPD from 1987 until his death in 1992. When the SPD moved its headquarters from Bonn back to Berlin in the mid-1990s, the new headquarters was named the "Willy Brandt Haus." | |

| − | |||

| − | Brandt was a member of the [[European Parliament]] from 1979 to 1983, and Honorary Chairman of the SPD from 1987 until his death in 1992. When the SPD moved its headquarters from Bonn back to Berlin in the mid-1990s, the new headquarters was named the "Willy Brandt Haus" | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Family == | == Family == | ||

| − | From 1941 until 1948 Brandt was married to Anna Carlotta Thorkildsen (daughter of a Norwegian father and a German-American mother). They had a daughter, Nina (1940). After Brandt and Thorkildsen | + | From 1941 until 1948 Brandt was married to Anna Carlotta Thorkildsen (daughter of a Norwegian father and a German-American mother). They had a daughter, Nina (1940). After Brandt and Thorkildsen divorced in 1946, he married Norwegian Rut Hansen in 1948. Hansen and Brandt had three sons: Peter (1948), Lars (1951) and Matthias (1961). Today, Peter is a historian, Lars is a painter and Matthias is an actor. After 32 years of marriage, Brandt divorced Rut in 1980. On December 9, 1983, Brandt married Brigitte Seebacher (b. 1946). Rut Brandt died in Berlin on July 28, 2006. |

=== Matthias as Günter Guillaume === | === Matthias as Günter Guillaume === | ||

| − | In 2003, Matthias Brandt took the part of Guillaume in the film '''Im Schatten der Macht''' ( | + | In 2003, Matthias Brandt took the part of Guillaume in the film '''Im Schatten der Macht''' (“In the Shadow of Power”) by German filmmaker Oliver Storz. The film deals with the Guillaume affair and Brandt's resignation. Matthias Brandt caused a minor controversy in Germany when it was publicized that he would take the part of the man who betrayed his father and made him resign in 1974. Earlier that year—when the Brandts and the Guillaumes took a vacation to Norway together—it was Matthias, then twelve years old, who was the first to discover that Guillaume and his wife “were typing mysterious things on type writers the whole night through.” |

=== Lars writing about his father === | === Lars writing about his father === | ||

| Line 115: | Line 111: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

'''Works in English (selected)''' | '''Works in English (selected)''' | ||

| − | * Brandt, Willy. ''People and Politics: The Years 1960-1975''. Boston: Little, Brown, 1978 ISBN | + | * Brandt, Willy. ''People and Politics: The Years 1960-1975''. Boston: Little, Brown, 1978. ISBN 978-0316106405 |

| − | * Brandt, Willy. ''In Exile; Essays, Reflections and Letters, 1933-1947''. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1971 ISBN | + | * Brandt, Willy. ''In Exile; Essays, Reflections and Letters, 1933-1947''. Philadelphia, P.A.: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1971. ISBN 978-0812276428 |

| − | * Brandt, Willy. ''A Peace Policy for Europe''. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1969 ISBN | + | * Brandt, Willy. ''A Peace Policy for Europe''. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1969. ISBN 978-0030730405 |

| − | * Brandt, Willy. ''Arms and Hunger''. New York: Pantheon Books, 1986 ISBN | + | * Brandt, Willy. ''Arms and Hunger''. New York: Pantheon Books, 1986. ISBN 978-0394554464 |

'''Biographies''' | '''Biographies''' | ||

| − | * Brandt, Lars ''Andenken'' | + | * Brandt, Lars. ''Andenken''. München: C. Hanser, 2006. ISBN 3446207104 (in German) |

| − | * Binder, David. ''The Other German: Willy Brandt's Life & Times''. Washington: New Republic Book Co, 1975 ISBN 9780915220090 | + | * Binder, David. ''The Other German: Willy Brandt's Life & Times''. Washington: New Republic Book Co, 1975. ISBN 9780915220090 |

| − | * Merseburger, Peter | + | * Merseburger, Peter. ''Willy Brandt''. Stuttgart: Dt. Verl.-Anst., 2002. ISBN 978-3421053282 (in German) |

| − | * Marshall, Barbara | + | * Marshall, Barbara. ''Willy Brandt: A Political Biography''. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0312164386 |

| − | * Meola, Nestore | + | * di Meola, Nestore. "Willy Brandt". Soveria Mannelli (Catanzaro): Rubbettino, 1998. ISBN 978-8872847121 |

| − | * Prittie, Terence. ''Willy Brandt | + | * Prittie, Terence. ''Willy Brandt: Portrait of a Statesman''. New York: Schocken Books, 1974. ISBN 978-0805235616 |

| − | * Viola, Tom. ''Willy Brandt. World | + | * Viola, Tom. ''Willy Brandt. World Leaders Past & Present''. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1988. ISBN 978-0877545125 |

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| + | All links retrieved May 15, 2023. | ||

| − | * [http://www. | + | * [http://www.brandt21forum.info/Bio_Brandt.htm Willy Brandt Biography] – Centre for Global Negotiations |

| − | * [http:// | + | * [http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/1971/ The Nobel Peace Prize 1971: Willy Brandt] – Nobelprize.org (The Nobel Foundation) |

| − | * [http://www.depauw.edu/news/index.asp?id=17907 | + | * [http://www.depauw.edu/news/index.asp?id=17907 “Willy Brandt Discusses 'German Unification and World Peace' at DePauw”] – News release detailing Brandt’s 1990 visit to DePauw University |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | {{Template:Nobel Peace Prize Laureates 1951-1975}} | |

| − | |||

| + | [[Category:Politicians and reformers]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Nobel Peace Prize Winners]] | ||

{{credit|132908809}} | {{credit|132908809}} | ||

Latest revision as of 10:55, 15 May 2023

Willy Brandt, born Herbert Ernst Karl Frahm (December 18, 1913 – October 8, 1992), was a German politician, chancellor of West Germany (1969–1974) and leader of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) (1964–1987). Because resistance from the opposition kept much of Brandt's domestic program from being implemented, his most important legacy is the Ostpolitik, a policy aimed at improving relations with East Germany, Poland, and the Soviet Union. This policy caused considerable controversy in West Germany, but won Brandt the Nobel Peace Prize in 1971. The citation stated that "the ideal of peace" had been a "guiding star" to the chancellor throughout his active political career."[1]

Brandt was forced to resign as chancellor in 1974 after it became known that one of his closest aides had been working for the East German secret service (Stasi). This became one of the biggest political scandals in postwar West German history. In retirement, he chaired the Brandt Commission, an independent enquiry into how to reduce the North-South divide, conserve the environment and build a world "in which sharing, justice and peace" prevails. The subsequent report, "North-South: A Program for Survival" published in 1980 anticipated many and materially contributed toward the goal enshrined in the United Nations' Millennium Development Goals[2]

Even though his period as chancellor ended in controversy, Brandt continued to use his intellect and his passion for peace and justice to promote debate about North-South equity, making a very valuable and enduring contribution to thinking about development, economics and third-world debt. His commission enabled several distinguished out-of-office politicians, such as Edward Heath, to contribute from their experience to some of the most important issues of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries and how to ensure planetary survival.

Because he had escaped from Nazi Germany and had no association with the Third Reich, Brandt was well placed to lead Germany's reconstruction as a economic power with a largely pacifist ethos and a willingness to submerge its national identity into a European one.[3] German reunification in 1990 owed much to Brandt’s policy of rapprochement with the East.

Early life and World War II

Brandt was born Herbert Ernst Karl Frahm in Lübeck, Germany to Martha Frahm, an unwed mother who worked as a cashier for a department store. His father was an accountant from Hamburg by the name of John Möller, whom Brandt never met.

He became an apprentice at the shipbroker and ship's agent F. H. Bertling. He joined the "Socialist Youth" in 1929 and the Social Democratic Party (SPD) in 1930. He left the SPD to join the more left wing Socialist Workers Party (SAPD), which was allied to the POUM in Spain and the ILP in Britain. In 1933, using his connections with the port and its ships from the time he had been apprentice, he left Germany for Norway on a ship to escape Nazi persecution. It was at this time that he adopted the pseudonym Willy Brandt to avoid detection by Nazi agents. In 1934, he took part in the founding of the International Bureau of Revolutionary Youth Organizations, and was elected to its secretariat.

Brandt visited Germany from September to December 1936, disguised as a Norwegian student named Gunnar Gaasland. In 1937, during the Civil War, he worked in Spain as a journalist. In 1938, the German government revoked his citizenship, so he applied for Norwegian citizenship. In 1940, he was arrested in Norway by occupying German forces, but he was not identified because he wore a Norwegian uniform. On his release, he escaped to neutral Sweden. In August 1940, he became a Norwegian citizen, receiving his passport from the Norwegian embassy in Stockholm, where he lived until the end of the war. Brandt returned to Sweden to lecture on December 1, 1940, at Bommersvik College about the problems experienced by the social democrats in Nazi Germany and the occupied countries at the start of World War II.

Mayor of West Berlin, foreign minister of West Germany

In late 1946, Brandt returned to Berlin, working for the Norwegian government.

In 1948, he joined the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) in Berlin. He became a German citizen again and formally adopted his pseudonym as his legal name.

Outspoken against the Soviet repression of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution and against Khrushchev's 1958 proposal that Berlin receive the status of a "free city," he was considered to belong to the right wing of his party, an assessment that would later change.

Brandt was supported by the powerful publisher Axel Springer. From October 3, 1957 to 1966, he was mayor of West Berlin, a particularly stressful time for the city with the construction of the Berlin Wall.

Brandt became chairman of the SPD in 1964, a post he retained until 1987.

Brandt was the SPD candidate for chancellor in 1961, but lost to Konrad Adenauer's conservative Christian Democratic Union (CDU). In 1965, he ran again, and lost to the popular Ludwig Erhard. But Erhard's government was short-lived, and, in 1966, a grand coalition between the SPD and CDU was formed; Brandt became foreign minister and vice chancellor.

Chancellor of West Germany

After the elections of 1969, again with Brandt as lead candidate, the SPD became stronger and after three weeks of negotiation formed a coalition government with the small liberal Free Democratic Party of Germany (FDP). Brandt was elected chancellor.

Foreign policy

As chancellor, Brandt gained more scope to develop his Ostpolitik. He was active in creating a degree of rapprochement with East Germany and in improving relations with the Soviet Union, Poland and other Eastern Bloc countries.

A seminal moment came in December 1970 with the famous Warschauer Kniefall in which Brandt, apparently spontaneously, knelt down at the monument to victims of Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. The uprising occurred during the military occupation of Poland and the monument is to those killed by German troops who suppressed the uprising and deported remaining ghetto residents to concentration camps.

Brandt was named TIME magazine's “Man of the Year” for 1970.

In 1971 Brandt received the Nobel Peace Prize for his work in improving relations with East Germany, Poland and the Soviet Union. In his Nobel Lecture, Brandt referred to the current conflict between India and Pakistan suggesting that what he had been able to achieve was "little enough" in the face if this new war. He continued:

War must not be a means to achieve political ends. Wars must be eliminated, not merely limited. No national interest can today be isolated from collective responsibility for peace. This fact must be recognized in all foreign relations. As a means of achieving European and worldwide security, therefore, foreign policy must aim to reduce tensions and promote communication beyond frontiers.[4]

In West Germany, Brandt's Ostpolitik was extremely controversial, dividing the populace into two camps: one side, most notably the victims of Stalinist ethnic cleansing from historical Eastern Germany and Eastern Europe, loudly voiced their opposition, calling the policy "illegal" and "high treason," while others applauded Brandt's move as aiming at "Wandel durch Annäherung" ("change through rapprochement," i.e., encouraging change through a policy of engagement rather than isolation). Supporters of Brandt claim his Ostpolitik did help to break down the Eastern Bloc's siege mentality and increase the awareness of the contradictions in their brand of socialism, which—together with other events—eventually led to its downfall. Ostpolitik was strongly opposed by the conservative parties and many social democrats as well.

Domestic policies

Political and social changes of the 1960s

West Germany in the late 1960s was shaken by student disturbances and a general 'change of the times' that not all Germans were willing to accept or approve. What had seemed a stable, peaceful nation, happy with its outcome of the "Wirtschaftswunder" ("economic miracle") turned out to be a deeply conservative, bourgeois, and insecure people with a lot of citizens unable to face their Nazi past. The younger generation, mostly students, took a very progressive stance toward Germany’s future and were a powerful voice against a way of life that they considered outdated and old-fashioned.

Brandt wins over the students

Brandt's predecessor, Kurt Georg Kiesinger, had been a member of the Nazi party. Brandt had been a victim of Nazi terror; no wider a gap could have existed between the two chancellors. Unlike Brandt, Kiesinger was unable to understand the students' political demands. For him, they were nothing but "a shameful crowd of long-haired drop-outs who needed a bath and someone to discipline them." The students (with a sizeable number of intellectuals backing them up) turned their parents' values and virtues upside down and questioned the West German society in general, seeking social, legal and political reforms.

On the domestic field, Brandt pursued exactly this—a course of social, legal and political reforms. In his first parliament speech after his election, Brandt signaled that he had comprehended what made the students go out and demonstrate against authority. In the speech he claimed his political course of reforms ending it with the famous summarizing words "Wir wollen mehr Demokratie wagen" ("Let's dare more democracy"). This made him—and the SPD, too—extremely popular among most students and other young West Germans who dreamed of a country quite different from the one their parents had built after the war. However, many of Brandt's reforms met the resistance of state governments (dominated by CDU/CSU). The spirit of reformist optimism was cut short by the 1973 Oil Crisis. Brandt's domestic policy has been criticized of having caused many of West Germany's economic problems.

Crisis in 1972

Because of these controversies, several members of his coalition switched sides. In May 1972, the opposition CDU believed it had the majority in the Bundestag (German parliament) and demanded a vote on a motion of no confidence (Misstrauensvotum). Had this motion passed, Rainer Barzel would have replaced Brandt as chancellor. To everyone's surprise, the motion failed. The margin was extremely narrow (two votes) and much later it was revealed that one or perhaps two members of the CDU had been paid off by the Stasi of East Germany to vote for Brandt.

Though Brandt remained chancellor, he had lost his majority. Subsequent initiatives in the Bundestag, most notably on the budget, failed. Because of this stalemate, the Bundestag was dissolved and new elections were called. Brandt's Ostpolitik, as well as his reformist domestic policies, were popular with parts of the young generation and led his SPD party to its best-ever federal election result in late 1972.

During the 1972 campaign, many popular West German artists, intellectuals, writers, actors and professors supported Brandt and the SPD. Among them were Günter Grass, Walter Jens, and even the football (soccer) player Paul Breitner. Public endorsements of the SPD via advertisements—and, more recently, internet pages—have become a widespread phenomenon since then.

To counter any notions about being sympathetic to communism or soft on left-wing extremists, Brandt implemented tough legislation that barred "radicals" from public service ("Radikalenerlass").

The Guillaume affair and Brandt's resignation

Around 1973, West German security organizations received information that one of Brandt's personal assistants, Günter Guillaume, was a spy for East Germany. Brandt was asked to continue work as usual, and he agreed, even taking a private vacation with Guillaume. Guillaume was arrested on April 24, 1974, and the West German government blamed Brandt for having a spy in his party. At the same time, some revelations about Brandt's private life (he had had some short-lived affairs with prostitutes) appeared in newspapers. Brandt contemplated suicide and even drafted a suicide note. He chose instead to accept responsibility for Guillaume, and resigned on May 7, 1974.

Guillaume had been a spy for East Germany, supervised by Markus Wolf, head of the Main Intelligence Administration of the East German Ministry for State Security. Wolf stated after the reunification that the resignation of Brandt had never been intended, and that the affair had been one of the biggest mistakes of the East German secret service. This was led 1957-1989 by Erich Mielke, an old follower of Stalin and Beria.

Brandt was succeeded as chancellor by the Social Democrat Helmut Schmidt, who, unlike Brandt, belonged to the right wing of his party. For the rest of his life, Brandt remained suspicious that his fellow social democrat and longtime rival Herbert Wehner had been scheming for his downfall, but evidence for this seems scant.

The story of Brandt and Guillaume is told in the play Democracy by Michael Frayn. The play follows Brandt's career from his election as the first left-of-center chancellor in West Germany in 40 years to his downfall at the hands of his trusted assistant Guillaume. The play examines Guillaume's dual identity as trusted personal assistant to the West German chancellor and Stasi spy, and Guillaume's conflict as his duty to Brandt's enemies clashes with his genuine love and admiration for the chancellor.

Later life

After his term as chancellor, Brandt remained head of his party, the SPD, until 1987 and retained his seat in the Bundestag. Brandt was head of the Socialist International from 1976 to 1992, which he called a world party of peace, working to enlarge that organization beyond the borders of Europe. In 1977, he was appointed chair of the Independent Commission for International Developmental Issues, which produced a report, in 1980, calling for drastic changes in the world's attitude to development in the Third World. This became known as the Brandt Report.

His continued interest in development issues are indicated by the title of his 1986 book, which links arms with hunger while the Centre for Global Negotiations has developed from his work, which is dedicated to promoting a global Marshall Plan type initiative. The Centre also has links with the Network of Spiritual Progressives, a project of the Tikkun community. Tikkun is the Hebrew phrase for "repairing," as in tikkun olam (to repair the world).[5]

In 1975, it was widely feared that Portugal would fall to communism; Brandt supported the Democratic Socialist Party of Mário Soares that won a major victory, thus keeping Portugal capitalist. He also supported Felipe González's newly legal socialist party in Spain after Franco's death.

In late 1989, Brandt became one of the first leftist leaders in West Germany to publicly favor reunification over some sort of two-state federation. His public statement "Now grows together what belongs together" was quoted frequently.

One of Brandt's last public appearances was flying to Baghdad, to free some Western hostages held by Saddam Hussein, after the invasion of Kuwait in 1990. He died of colon cancer at his home in Unkel, a town on the Rhine, and was given the first German state funeral since 1929. He was buried at the cemetery at Zehlendorf in Berlin.

Brandt was a member of the European Parliament from 1979 to 1983, and Honorary Chairman of the SPD from 1987 until his death in 1992. When the SPD moved its headquarters from Bonn back to Berlin in the mid-1990s, the new headquarters was named the "Willy Brandt Haus."

Family

From 1941 until 1948 Brandt was married to Anna Carlotta Thorkildsen (daughter of a Norwegian father and a German-American mother). They had a daughter, Nina (1940). After Brandt and Thorkildsen divorced in 1946, he married Norwegian Rut Hansen in 1948. Hansen and Brandt had three sons: Peter (1948), Lars (1951) and Matthias (1961). Today, Peter is a historian, Lars is a painter and Matthias is an actor. After 32 years of marriage, Brandt divorced Rut in 1980. On December 9, 1983, Brandt married Brigitte Seebacher (b. 1946). Rut Brandt died in Berlin on July 28, 2006.

Matthias as Günter Guillaume

In 2003, Matthias Brandt took the part of Guillaume in the film Im Schatten der Macht (“In the Shadow of Power”) by German filmmaker Oliver Storz. The film deals with the Guillaume affair and Brandt's resignation. Matthias Brandt caused a minor controversy in Germany when it was publicized that he would take the part of the man who betrayed his father and made him resign in 1974. Earlier that year—when the Brandts and the Guillaumes took a vacation to Norway together—it was Matthias, then twelve years old, who was the first to discover that Guillaume and his wife “were typing mysterious things on type writers the whole night through.”

Lars writing about his father

In early 2006, Lars Brandt published a biography about his father called "Andenken" ("Remembrance"). The book has been the subject of some controversy. Some see it as a loving memory of a father-son-relationship. Others label the biography a ruthless statement of a son who still thinks he had never had a father who really loved him.

Notes

- ↑ The Nobel Foundation (1971), The 1971 Nobel Peace Prize - Presentation Speech, Nobelprize.org. Retrieved June 26, 2007.

- ↑ James Bernard Quilligan, The Brandt Equation: 21st Century Blueprint for the New Global Economy, Centre for Global Negotiations. Retrieved June 16, 2007.

- ↑ Nile Gardiner, "President Bush in Europe: Shaping US Policy toward Germany," Heritage.org (July 26, 2006). Retrieved June 16, 2007.

- ↑ Willy Brandt, "Nobel Lecture", Nobelprize.org. Retrieved June 16, 2007.

- ↑ What is the Global Marshall Plan? The Network of Spiritual Progressives. Retrieved June 16, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Works in English (selected)

- Brandt, Willy. People and Politics: The Years 1960-1975. Boston: Little, Brown, 1978. ISBN 978-0316106405

- Brandt, Willy. In Exile; Essays, Reflections and Letters, 1933-1947. Philadelphia, P.A.: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1971. ISBN 978-0812276428

- Brandt, Willy. A Peace Policy for Europe. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1969. ISBN 978-0030730405

- Brandt, Willy. Arms and Hunger. New York: Pantheon Books, 1986. ISBN 978-0394554464

Biographies

- Brandt, Lars. Andenken. München: C. Hanser, 2006. ISBN 3446207104 (in German)

- Binder, David. The Other German: Willy Brandt's Life & Times. Washington: New Republic Book Co, 1975. ISBN 9780915220090

- Merseburger, Peter. Willy Brandt. Stuttgart: Dt. Verl.-Anst., 2002. ISBN 978-3421053282 (in German)

- Marshall, Barbara. Willy Brandt: A Political Biography. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0312164386

- di Meola, Nestore. "Willy Brandt". Soveria Mannelli (Catanzaro): Rubbettino, 1998. ISBN 978-8872847121

- Prittie, Terence. Willy Brandt: Portrait of a Statesman. New York: Schocken Books, 1974. ISBN 978-0805235616

- Viola, Tom. Willy Brandt. World Leaders Past & Present. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1988. ISBN 978-0877545125

External links

All links retrieved May 15, 2023.

- Willy Brandt Biography – Centre for Global Negotiations

- The Nobel Peace Prize 1971: Willy Brandt – Nobelprize.org (The Nobel Foundation)

- “Willy Brandt Discusses 'German Unification and World Peace' at DePauw” – News release detailing Brandt’s 1990 visit to DePauw University

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.