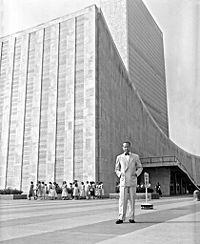

Dag Hammarskjöld

Dag Hjalmar Agne Carl Hammarskjöld (July 29, 1905 – September 18, 1961) was a Swedish diplomat and the second secretary-seneral of the United Nations. He served from April 18, 1953 until his death in a plane crash on September 18, 1961.

As secretary-general, Hammarskjöld took the stance that he was not representing his own nation but he was a representative of the international community. When he contemplated decisions and undertook action, he always kept this in mind. Hammarskjöld was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize posthumously for his dedication to achieving lasting peace. He was succeeded as secretary-general by U Thant.

Hammarskjöld was a man who sought a close relationship with God. His personal journal, published following his death under the title Markings', revealed the footprints of his spiritual journey. He was known to say, "The more faithfully you listen to the voices within you, the better you will hear what is sounding outside."

Early life and Education

Hammarskjöld was born in Jönköping, Sweden. He lived most of his childhood in the college town of Uppsala. Hammarskjöld was the fourth and youngest son of Hjalmar Hammarskjöld, Swedish prime minister (1914–1917), and Agnes Almquist. His ancestors had served the Swedish crown since the seventeenth century. During his youth, Hammarskjöld’s father was governor of Uppland County.

He began his studies at Uppsala University when he was 18. In 1925, Hammarskjöld graduated with honors, earning a Bachelor of Arts degree. His majors were linguistics, literature and history. He continued his studies at Uppsala, pursuing and earning a Master's degree in economics in 1928 and a Bachelor of Laws degree in 1930. He then moved to Stockholm.

Career in Swedish Government

From 1930 to 1934 Hammarskjöld was secretary of a governmental committee on unemployment. He also wrote his doctoral thesis, Konjunkturspridningen (The Spread of the Business Cycle). Hammarskjöld received his doctorate in economics from Stockholm University in 1933. For the next several years, he worked as assistant professor of political economics at the University of Stockholm.

In 1936 he became secretary of the Sveriges Riksbank (Bank of Sweden). After only a year, Hammarskjöld was appointed as permanent undersecretary of the Ministry of Finance, which was considered one of the most difficult jobs in the government. From 1941 to 1948 he also served as chairman of the board of the National Bank of Sweden, also a government appointment. He was the first to have both assignments simultaneously.

As 1945 began, Hammarskjöld became adviser to the Cabinet on financial and economic problems. In this position he coordinated government plans to alleviate the economic problems of the post-World War II period.

Hammarskjöld was appointed to Sweden's Ministry for Foreign Affairs in 1947, continuing his responsibility for handling economic issues. Two years later, he became the state secretary for foreign affairs.

Also in 1947, he was a delegate to the Paris conference that established the Marshall Plan. He went to Paris again in 1948 to attend the conference of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Hammarskjöld became head of the Sweden delegation to UNISCAN in 1950. This organization was created for the purpose of promoting economic cooperation between the United Kingdom and the Scandinavian countries. The next year, he became a cabinet minister without portfolio—essentially, deputy foreign minister. Although Hammarskjöld served with a cabinet dominated by the Social Democrats, he never officially joined any political party.

In 1951, Hammarskjöld became vice chairman of the Swedish delegation to the Sixth Regular Session of the United Nations General Assembly in Paris. He became the acting chairman of the Swedish delegation to the seventh General Assembly in New York in 1952.

On December 20, 1954, Hammarskjöld was elected to take his father's vacated seat in the Swedish Academy. The Swedish Academy is the organization that is charged with choosing Nobel Prize recipients.

UN Secretary General

When Trygve Lie resigned from his post as UN secretary-general in 1953, the Security Council recommended Hammarskjöld to the post, which came as a surprise to him. The UN General Assembly elected him unanimously in the April 7–10 session. In 1957, he was re-elected.

Hammarskjöld, known as a knowledgeable and unassuming man, had no illusions about the secretary-general role being an easy one. Those who knew him testified that he gave himself completely to the responsibility with all his strength and determination.

Hammarskjöld started his term by defining the role and responsibilities of the Secretariat and the secretary-general. He believed that it was the duty of both to gather complete objective information about aims and difficulties of member states. But he also believed that the secretary-general was obliged to form an opinion based on the rules of the UN Charter and never betray those rules.

Nearing the end of 1953, Hammarskjöld reflected,

Our work for peace must begin within the private world of each one of us. To build for man a world without fear, we must be without fear. To build a world of justice, we must be just. And how can we fight for liberty if we are not free in our own minds? How can we ask others to sacrifice if we are not ready to do so? Only in true surrender to the interest of all can we reach that strength and independence, that unity of purpose that equity of judgement which are necessary if we are to measure up to our duty to the future, as men of a generation to whom the chance was given to build in time a world of peace.

Hammarskjöld devoted himself to solving disputes through private discussions between parties of the dispute, thoroughly dedicating himself to this quiet diplomacy. During his terms, Hammarskjöld tried to soothe relations between Israel and the Arab states. In 1955 he went to mainland China to negotiate the release of 15 American pilots who had served in the Korean War and been captured by the Chinese. In 1956 he established the United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF). In 1957 he intervened in the Suez Crisis.

In 1960 the former Belgian colony and now newly-independent Congo asked for UN aid in defusing the escalating civil strife. Hammarskjöld made four trips to the Congo. However, his efforts towards the decolonization of Africa were considered insufficient by the Soviet Union. In September 1960 the Soviet Union denounced his decision to send a UN emergency force to keep the peace. They demanded his resignation and the replacement of the office of secretary-general by a three-man directorate with a built in veto, the troika. According to the memoirs of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, the objective was to "equally represent interests of three groups of countries: capitalist, socialist and recently independent."[1]

Hammarskjöld remained firm to the end that the independent authority of the United Nations be strengthened. His position made him the object of attack, sometimes by the West, but more frequently and intensely by the Soviet Union. He firmly believed and stated that it was not the Soviet Union or any of the other great powers that needed the vigilant protection of the UN, but all the other nations.

Gunnar Jahn, chairman of the Nobel Committee in 1961, credited Hammarskjöld during the Nobel Prize presentation speech, with standing firm in the face of criticism and attacks, never wavering from his path, which resulted in the UN "becoming an effective and constructive international organization, capable of giving life to the principles and aims expressed in the UN Charter, administered by men who both felt and acted internationally. The goal he always strove to attain was to make the UN Charter the one by which all countries regulated themselves."

Death

In September 1961, Hammarskjöld learned of fighting between noncombatant UN forces and Katanga Province troops of Moise Tshombe. He was en route to negotiate a ceasefire on the night of September 17-18 when his plane crashed near Ndola, Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia). He and fifteen others perished.

There is still speculation as to the cause of the crash. The explanation of investigators at the time is that Hammarskjöld's aircraft descended too low on its approach to Ndola's airport at night. The crew had filed no flight plan for security reasons. No evidence of a bomb, surface-to-air missile or hijacking has ever been presented. It has been speculated that the crew of the Douglas DC-6 incorrectly used altitude data for Ndolo (915 feet/279 meters), in Congo and at lower altitude, rather than Ndola (4,167 feet/1,270 meters) in Northern Rhodesia.

On August 19, 1998, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, chairman of South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), revealed that previously uncovered letters had implicated British MI5, American CIA and South African intelligence services in the 1961 crash of Dag Hammarskjöld's plane. One TRC letter said that a bomb in the aircraft's wheel bay was set to detonate when the wheels came down for landing.[2]

On July 29, 2005, exactly one hundred years after Hammarskjöld's birth, Norwegian Major General Bjørn Egge gave an interview to the newspaper Aftenposten on the events surrounding Hammarskjöld's death. According to Egge, who was the first UN officer to see the body, Hammarskjöld had a hole in his forehead, and this hole was subsequently airbrushed from photos taken of the body. It appeared to Egge that Hammarskjöld had been thrown from the plane, and grass and leaves in his hands may have indicated that he survived the crash, and had tried to scramble away from the wreckage. Egge's statement does not align with Archbishop Tutu's information.[3]

A less conspiratorial theory holds that Hammarskjöld's plane struck some treetops as it was preparing for landing. Hammarskjöld was the only person whose body was separate from the wreckage and therefore not burnt. He was thrown from the crash, able to crawl away from the plane, but his injuries were severe enough that he was already dead by the time the plane was found.

Hammarskjöld's only book, Vägmärken (Markings), was published in 1963. The book is a collection of his diary reflections. It begins in 1925 when he was 20 years old, and ends at his death in 1961.[4] Hammarskjöld reveals himself as a Christian mysticist through the journal entries. In his journal entries, he describes his diplomat life in terms of an ”inner journey.” The book became popular with U.S. students and the former Swedish archbishop K. G. Hammar.

Legacy

Today, many view Hammarskjöld as the greatest United Nations secretary-general because of his ability to shape events.

Kofi Annan stated in a speech about Hammarskjöld,

His life and his death, his words and his actions, have done more to shape public expectations of the office, and indeed of the [United Nations] Organization, than those of any other man or woman in its history. His wisdom and his modesty, his unimpeachable integrity and single-minded devotion to duty, have set a standard for all servants of the international community—and especially, of course for his successors—which is simply impossible to live up to. There can be no better rule of thumb for a Secretary General, as he approaches each new challenge or crisis, than to ask himself, "How would Hammarskjöld have handled this?" What is clear is that his core ideas remain highly relevant in this new international context. The challenge for us is to see how they can be adapted to take account of it."[5]

Not long after Hammarskjöld's death, many cities around the world renamed streets and squares in honor of him.

A Manhattan park near the United Nations headquarters is called Dag Hammarskjöld Plaza.

The United Nations, desiring to establish a fitting memorial in commemoration of Dag Hammarskjöld's service to the organization, elected to name its new library after Hammarskjöld. The library was dedicated on November 16, 1961.

Hammarskjöld was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize posthumously in November 1961, "in gratitude for all he did, for what he achieved, for what he fought for: to create peace and goodwill among nations and men."

Notes

- ↑ United Nations Radio History (in Russian) Retrieved July 11, 2007.

- ↑ “UN assassination plot denied,” BBC News (August 19, 1998). Retrieved July 11, 2007.

- ↑ Cato Guhnfeldt, “Så hull i pannen” (in Norwegian), Aftenposten (July 28, 2005).

- ↑ Thom Hartmann, “Markings - the spiritual diary of Dag Hammarskjöld,” BuzzFlash.com (March 3, 2005). Retrieved July 11, 2007.

- ↑ Kofi Annan, "Dag Hammarskjöld and the 21st Century" (speech given September 6, 2001, in Uppsala, Sweden).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ask, Sten and Anna Mark-Jungkvist. The Adventure of Peace: Dag Hammarskjöld and the Future of the UN. New York, Scribner, 1966. Reprint edition, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005. ISBN 978-1403974310

- Cordier, Andrew W. The Quest for Peace: The Dag Hammerskjöld Memorial Lectures. New York: Columbia University Press, 1965.

- Jordan, Robert S. Dag Hammarskjöld Revisited: The UN Secretary-General as a Force in World Politics. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 1983. ISBN 978-0890892336

- Lash, Joseph P. Dag Hammarskjold, Custodian of the Brushfire Peace. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1961.

- Meisler, Stanley. United Nations: The First Fifty Years. New York: The Atlantic Monthly Press, 1995. ISBN 0871136562

- Miller, Richard I. Dag Hammarskjöld and Crisis Diplomacy. New York: Oceana Publications, 1961.

- Stolpe, Sven. Dag Hammarskjöld, A Spiritual Portrait. New York: Scribner, 1966.

- Urguhart, Brain. Hammarskjöld. New York: Knopf, 1972. ISBN 978-0394479606

- Zacher, Mark W. Dag Hammarskjöld's United Nations. New York: Columbia University Press, 1970. ISBN 978-0231032759

External links

All links retrieved January 12, 2024.

- Dag Hammarskjöld: The UN Years – United Nations

| Preceded by: Trygve Lie |

United Nations Secretary-General 1953-1961 |

Succeeded by: U Thant |

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.