Reich, Wilhelm

| (40 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} |

| − | |||

[[Category:Psychologists]] | [[Category:Psychologists]] | ||

{{epname|Reich, Wilhelm}} | {{epname|Reich, Wilhelm}} | ||

| + | {{Infobox person | ||

| + | | name = Wilhelm Reich | ||

| + | | image = Wilhelm Reich.jpg | ||

| + | | caption = Portrait by Ludwig Gutmann [[Vienna]], before 1943 | ||

| + | | birth_date = {{Birth date|1897|3|24|mf=yes}} | ||

| + | | birth_place = [[Dobrianychi|Dobzau]], [[Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria]], [[Austria-Hungary]]<br />{{small|(now [[Dobrianychi]], [[Lviv Oblast]], [[Ukraine]])}} | ||

| + | | death_date = {{Death date and age|1957|11|3|1897|3|2|mf=yes}} | ||

| + | | death_place = [[United States Penitentiary, Lewisburg]], [[Pennsylvania]], U.S. | ||

| + | | resting_place = [[Orgonon]], [[Rangeley, Maine]], U.S. | ||

| + | | nationality = Austrian | ||

| + | | education = [[University of Vienna]] ([[Doctor of Medicine|MD]], 1922) | ||

| + | | known_for = Character analysis<br>muscular armour<br>[[orgastic potency]]<br>[[vegetotherapy]]<br>[[Freudo-Marxism]]<br>[[orgone]] | ||

| + | | notable_works = {{Plainlist|class=| | ||

| + | * ''[[The Function of the Orgasm]]'' (1927) | ||

| + | * ''[[Character Analysis]]'' (1933) | ||

| + | * ''[[The Mass Psychology of Fascism]]'' (1933) | ||

| + | * ''[[Die Sexualität im Kulturkampf|The Sexual Revolution]]'' (1936) | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | | parents = {{Plainlist| | ||

| + | * Leon Reich, Cecilia Roniger | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | | relatives = Robert Reich (brother) | ||

| + | | partner = {{Plainlist| | ||

| + | * [[Annie Reich]], née Pink (m. 1922–1933) | ||

| + | * Elsa Lindenberg (1932–1939) | ||

| + | * Ilse Ollendorf (m. 1946–1951) | ||

| + | * Aurora Karrer (1955–1957) | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | | children = {{Plainlist| | ||

| + | * [[Eva Reich]] (1924–2008) | ||

| + | * Lore Reich Rubin (b. 1928) | ||

| + | * Peter Reich (b. 1944) | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | '''Wilhelm Reich''' (March 24, 1897 – November 3, 1957) was an Austrian-American [[Psychiatry|psychiatrist]] and [[Psychoanalysis|psychoanalyst]]. He was a respected analyst for much of his life, focusing on character structure, rather than on individual [[Neurosis|neurotic]] symptoms. He promoted [[adolescence|adolescent]] [[human sexuality|sexuality]], the availability of [[contraceptive]]s and [[abortion]], and the importance for women of economic independence. Reich's work influenced thinkers such as [[Alexander Lowen]], [[Fritz Perls]], [[Paul Goodman (writer)|Paul Goodman]], [[Saul Bellow]], [[Norman Mailer]], and [[William Burroughs]]. His work synthesized material from psychoanalysis, [[cultural anthropology]], [[economics]], [[sociology]], and [[ethics]]. | ||

| − | + | Reich became a controversial figure for his studies on the link between [[human sexuality]] and [[neurosis|neuroses]], emphasizing "[[Orgasm|orgastic potency]]" as the foremost criterion for psycho-physical health. He said he had discovered a form of [[energy]] that permeated the atmosphere and all living matter, which he called "[[orgone]]." He built boxes called "orgone accumulators," which patients could sit inside, and which were intended to harness the energy for what he believed were its [[health]] benefits. It was this work, in particular, that cemented the rift between Reich and the [[psychiatry|psychiatric]] establishment. His experiments and commercialization of the orgone box brought Reich into conflict with the U.S. [[Food and Drug Administration]], leading to a lawsuit, conviction, and incarceration. He died in [[prison]]. | |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| − | + | Although Reich's early work was overshadowed by the controversy and loss of credibility of his later work, his influence has been significant. While his ideas may have strained the limits of scientific respectability, as well as morality, Reich's desire and efforts were for the betterment of humankind. His realization that sexual energy is potent rings true; it is harnessing that energy successfully in a moral and ethical manner that is the challenge, one in which Reich did not find the correct answer. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Reich became a controversial figure for his studies on the link between [[human sexuality]] and neuroses, emphasizing "[[Orgasm|orgastic potency]]" as the foremost criterion for psycho-physical health. He said he had discovered a form of energy that permeated the atmosphere and all living matter, which he called "[[orgone]]." He built boxes called "orgone accumulators," which patients could sit inside, and which were intended to harness the energy for what he believed were its health benefits. It was this work, in particular, that cemented the rift between Reich and the psychiatric establishment. | ||

| − | Reich was | + | ==Life== |

| + | '''Wilhelm Reich''' was born in 1897 to Leon Reich, a prosperous farmer, and Cecilia Roniger, in Dobrzanica,<ref> Also written as ''Dobryanichi'' or '''Dobrjanici'' (in Ukrainian: Добряничі), village near Peremyshliany, now in [[Ukraine]]</ref> a village in [[Galicia (Central Europe)|Galicia]], then part of the [[Austria-Hungary|Austro-Hungarian Empire]]. Three years after his birth, the couple had a second son, Robert. | ||

| − | == | + | His father was by all accounts strict, cold, and jealous. He was [[Jew]]ish, but Reich was later at pains to point out that his father had moved away from [[Judaism]] and had not raised his children as Jews; Reich was not allowed to play with [[Yiddish]]-speaking children,<ref name=Sharaf39>Myron Sharaf, ''Fury on Earth: A Biography of Wilhelm Reich'' (New York: Da Capo Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0306805752), 39.</ref> and as an adult did not want to be described as Jewish.<ref name=Sharaf463>Sharaf, 463.</ref> |

| − | + | Shortly after his birth, the family moved south to a farm in Jujinetz, near [[Chernivtsi]], [[Bukovina]], where Reich's father took control of a cattle farm owned by his mother's family. Reich attributed his later interest in the study of sexuality and the biological basis of the emotions to his upbringing on the farm where, as he later put it, the "natural life functions" were never hidden from him.<ref>Wilhelm Reich, "Background and scientific development of Wilhelm Reich," ''Orgone Energy Bulletin'' V (1953): 6, cited in Sharaf 1994, 40, 488, footnote 10.</ref> | |

| − | + | He was taught at home until he was 12, when his mother committed [[suicide]] after being discovered by her husband of having an affair with Reich's tutor, who lived with the family. He wrote that his "joy of life [was] shattered, torn apart from [his] inmost being for the rest of [his] life!"<ref name=Reichpubertäet>Wilhelm Reich, "Ueber einen Fall von Durchbruch der Inzestschranke in der Pubertät," ''Zeitschrift für Sexualwissenschaft,'' VII, (1920): 222-223, cited in and translated by Sharaf, 43 and 448, footnote 12.</ref> | |

| − | + | The tutor was sent away, and Reich was left without his mother or his teacher, and with a powerful sense of guilt.<ref name=Sharaf42>Sharaf, 42-46.</ref> He was sent to the all-male Czernowitz [[gymnasium (school)|gymnasium]], excelling at Latin, Greek, and the natural sciences. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Reich's father was "completely broken" by his wife's suicide.<ref>Wilhelm Reich, "Ueber einen Fall von Durchbruch der Inzestschranke in der Pubertät," cited in Sharaf, 489, footnote 21.</ref> He contracted [[pneumonia]] and then [[tuberculosis]], and died in 1914 as a result of his illness; despite his insurance policy, no money was forthcoming. | |

| − | + | Reich managed the farm and continued with his studies, graduating in 1915 ''mit Stimmeneinhelligkeit'' (unanimous approval). In the summer of 1915, the Russians invaded Bukovina and the Reich brothers fled to [[Vienna]], losing everything. In his ''Passion of Youth,'' Reich wrote: "I never saw either my homeland or my possessions again. Of a well-to-do past, nothing was left."<ref name=bio>[https://wilhelmreichmuseum.org/about/biography-of-wilhelm-reich/ Biography] ''The Wilhelm Reich Museum''. Retrieved November 17, 2023.</ref> | |

| − | + | [[Image:Sigmund Freud-loc.jpg|right|thumb|300px|[[Sigmund Freud]] and Reich met in 1919 when Reich needed literature for a [[sexology]] seminar.]] | |

| + | Reich joined the Austrian Army after school, serving from 1915-1918, for the last two years as a [[lieutenant]]. | ||

| − | Reich | + | In 1918, when the war ended, he entered the medical school at the [[University of Vienna]]. As an undergraduate, he was drawn to the work of [[Sigmund Freud]]; the men first met in 1919 when Reich visited Freud to obtain literature for a seminar on [[sexology]]. Freud left a strong impression on Reich. Freud allowed him to start seeing analytic patients as early as 1920. Reich was accepted as a guest member of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Association in the summer of 1920, and became a regular member in October 1920, at the age of 23.<ref name=Sharaf58>Sharaf, 58.</ref> Reich's brilliance as an analyst and author of numerous important articles on psychoanalysis caused Freud to select him as a first assistant physician when Freud organized the Psychoanalytic-Polyclinic in Vienna in 1922. It was at the Vienna Psychoanalytic Association that Reich met Annie Pink, a patient of his and later an analyst herself.<ref> Edith Jacobsen, [https://pep-web.org/browse/document/ijp.052.0334a?page=P0334 Annie Reich (1902-1971)] ''International Journal of Psychoanalysis'' 52 (1971): 334-336. Retrieved Novemebr 17, 2023.</ref> They married and had two daughters, Eva in 1924<ref>Eva Reich became a doctor and applied orgonomical techniques to the care of newborns.</ref> and Lore in 1928.<ref>Lore Reich Rubin became a doctor and psychoanalyst.</ref> The couple separated in 1933, leaving the children with their mother. |

| − | Reich | + | Reich was allowed to complete his six-year medical degree in four years because he was a war veteran, and received his [[Doctor of Medicine|M.D.]] in July 1922.<ref name=bio/> |

| − | |||

| − | + | Reich was very outspoken about Germany’s turbulent political climate. Unlike most members of the Berlin Psychoanalytic Association, Reich openly opposed the rise of the [[Nazi]] Party. In 1933 he was denounced by the Communist Party, forced to flee from Germany when [[Hitler]] came to power, and expelled from the International Psychoanalytic Association in 1934. | |

| − | + | Reich was invited to teach at the New School for Social Research in New York City and on August 19, 1939 Reich sailed for America on the last ship to leave Norway before [[World War II]] broke out. Reich settled in the Forest Hills section of New York City and in 1946, married Ilse Ollendorf, with whom he had a son, Peter. | |

| − | Reich | ||

| − | + | Reich died in his sleep of heart failure on November 3, 1957 in the federal penitentiary in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

==His work== | ==His work== | ||

===Early career=== | ===Early career=== | ||

| − | He worked in internal medicine at University Hospital, Vienna, and studied neuropsychiatry from 1922- | + | He worked in internal medicine at University Hospital, Vienna, and studied [[neuropsychiatry]] from 1922-1924 at the Neurological and Psychiatric Clinic under Professor [[Julius Wagner-Jauregg|Wagner-Jauregg]], who won the [[Nobel Prize]] in medicine in 1927. |

| − | In 1922, he set up private practice as a psychoanalyst, and became a clinical assistant, and later deputy director, at Freud's Psychoanalytic Polyclinic. He joined the faculty of the Psychoanalytic Institute in Vienna in 1924, and conducted research into the social causes of [[neurosis]] | + | In 1922, he set up private practice as a psychoanalyst, and became a clinical assistant, and later deputy director, at [[Sigmund Freud]]'s Psychoanalytic Polyclinic. He joined the faculty of the Psychoanalytic Institute in Vienna in 1924, and conducted research into the social causes of [[neurosis]]. Reich's second wife, Elsa Lindenburg, was trained in [[Laban Movement Analysis|Laban movement analysis]], and was a pupil of [[Elsa Gindler]], who had started to develop a system of breathing and somatic responsiveness named ''Arbeit am Menschen'' in 1910. Reich first presented the principles of his vegetotherapy in a paper on "Psychic contact and vegetative current" in August 1934 at the 13th International Congress of Psychoanalysis at Lucerne, Switzerland, and went on to develop the technique between 1935 and 1940. |

| − | Reich developed a theory that the ability to feel sexual love depended on a physical ability to make love with what he called "orgastic potency." He attempted to measure the male [[orgasm]], noting that four distinct phases occurred physiologically: first, the psychosexual build-up or tension; second, the [[tumescence]] of the [[penis]], with an accompanying "charge," which Reich measured [[Electricity|electrically]]; third, an electrical discharge at the moment of orgasm; and fourth, the relaxation of the penis. He believed the force that he measured was a distinct type of energy present in all [[lifeform|life forms]] and later called it "orgone."<ref name=Cantwell/> | + | Reich developed a theory that the ability to feel sexual love depended on a physical ability to make love with what he called "orgastic potency." He attempted to measure the male [[orgasm]], noting that four distinct phases occurred physiologically: first, the psychosexual build-up or tension; second, the [[tumescence]] of the [[penis]], with an accompanying "charge," which Reich measured [[Electricity|electrically]]; third, an electrical discharge at the moment of orgasm; and fourth, the relaxation of the penis. He believed the force that he measured was a distinct type of energy present in all [[lifeform|life forms]] and later called it "orgone."<ref name=Cantwell>Alan Cantwell, [https://www.newdawnmagazine.com/articles/dr-wilhelm-reich-scientific-genius-or-medical-madman Dr. Wilhelm Reich: Scientific Genuis or Medical Madman?] ''New Dawn'' 84 (May–June 2004). Retrieved November 17, 2023.</ref> |

He was a prolific writer for psychoanalytic journals in [[Europe]]. Originally, psychoanalysis was focused on the treatment of neurotic symptoms. Reich's ''Character Analysis'' was a major step in the development of what today would be called "ego psychology." In Reich's view, a person's entire character, not only individual symptoms, could be looked at and treated as a neurotic phenomenon. The book also introduced Reich's theory of "body armoring." He argued that unreleased psychosexual energy could produce actual physical blocks within muscles and [[Organ (anatomy)|organs]], and that these act as a "body armor," preventing the release of the energy. An orgasm was one way to break through the armor. These ideas developed into a general theory of the importance of a healthy [[Human sexual behavior|sex life]] to overall well-being, a theory compatible with Freud's views. | He was a prolific writer for psychoanalytic journals in [[Europe]]. Originally, psychoanalysis was focused on the treatment of neurotic symptoms. Reich's ''Character Analysis'' was a major step in the development of what today would be called "ego psychology." In Reich's view, a person's entire character, not only individual symptoms, could be looked at and treated as a neurotic phenomenon. The book also introduced Reich's theory of "body armoring." He argued that unreleased psychosexual energy could produce actual physical blocks within muscles and [[Organ (anatomy)|organs]], and that these act as a "body armor," preventing the release of the energy. An orgasm was one way to break through the armor. These ideas developed into a general theory of the importance of a healthy [[Human sexual behavior|sex life]] to overall well-being, a theory compatible with Freud's views. | ||

| − | Reich agreed with Freud that sexual development was the origin of mental disorder. They both believed that most psychological states were dictated by [[Unconscious mind|unconscious]] processes; that infant sexuality develops early but is repressed, and that this has important consequences for [[mental health]]. At that time a [[Marxism|Marxist]], Reich argued that the source of sexual repression was [[Bourgeoisie|bourgeois]] morality and the socio-economic structures that produced it. As sexual repression was the cause of the [[Neurosis|neuroses]], the best cure would be to have an active, guilt-free sex life. He argued that such a liberation could come about only through a morality not imposed by a repressive economic structure.<ref name=Daloia>D'Aloia, | + | Reich agreed with Freud that sexual development was the origin of [[mental disorder]]. They both believed that most psychological states were dictated by [[Unconscious mind|unconscious]] processes; that infant sexuality develops early but is repressed, and that this has important consequences for [[mental health]]. At that time a [[Marxism|Marxist]], Reich argued that the source of sexual repression was [[Bourgeoisie|bourgeois]] morality and the socio-economic structures that produced it. As sexual repression was the cause of the [[Neurosis|neuroses]], the best cure would be to have an active, guilt-free sex life. He argued that such a liberation could come about only through a morality not imposed by a repressive economic structure.<ref name=Daloia>Alessandro D'Aloia, [http://www.marxist.com/marxism-psychoanalysis-wilhelm-reich.htm Marxism and Psychoanalysis: Notes on Wilhelm Reich’s Life and Works] ''Marxist.com''. Retrieved November 17, 2023.</ref> In 1928, he joined the Austrian Communist Party and founded the ''Socialist Association for Sexual Counselling and Research,'' which organized counseling centers for workers — in contrast to Freud, who was perceived as treating only the bourgeoisie. |

| − | Reich employed an unusual therapeutic method. He used touch to accompany the talking cure, taking an active role in sessions, feeling his patients' chests to check their breathing, repositioning their bodies, and sometimes requiring them to remove their clothes, | + | Reich employed an unusual therapeutic method. He used touch to accompany the talking cure, taking an active role in sessions, feeling his patients' chests to check their breathing, repositioning their bodies, and sometimes requiring them to remove their clothes, treating them in their underwear. These methods caused a split between Reich and the rest of the psychoanalytic community.<ref name=Cantwell/> |

| − | In 1930, he moved his practice to [[Berlin]] and joined the [[Communist Party of Germany]]. His best-known book, ''The Sexual Revolution'' | + | In 1930, he moved his practice to [[Berlin]] and joined the [[Communist Party of Germany]]. His best-known book, ''The Sexual Revolution,'' was published at this time in Vienna. Advocating free [[contraceptive]]s and [[abortion]] on demand, he again set up clinics in working-class areas and taught [[sex education]], but became too outspoken even for the [[communism|communist]]s, and eventually, after his book ''The Mass Psychology of Fascism'' was published, he was expelled from the party in 1933. |

| − | In this book, Reich categorized [[fascism]] as a symptom of sexual repression. The book was banned by the Nazis when they came to power. He realized he was in danger and hurriedly left Germany disguised as a tourist on a ski trip to Austria. Reich was expelled from the International Psychological Association in 1934 for political militancy | + | In this book, Reich categorized [[fascism]] as a symptom of sexual repression. The book was banned by the Nazis when they came to power. He realized he was in danger and hurriedly left Germany disguised as a tourist on a ski trip to Austria. Reich was expelled from the International Psychological Association in 1934 for political militancy. According to his daughter Lore, [[Anna Freud]] and [[Ernest Jones]] were behind the expulsion of Reich.<ref>Lore Reich, [https://pep-web.org/browse/document/IFP.012.0109A Wilhelm Reich and Anna Freud: His Expulsion from Psychoanalysis] ''International Forum of Psychoanalysis'' 12(2-3) (2003):109-117. Retrieved November 17, 2023. </ref> He spent some years in Denmark, Sweden, and Norway, before leaving for the United States in 1939. |

===The bion experiments=== | ===The bion experiments=== | ||

| + | From 1934-1937, based for most of the period in [[Oslo]], Reich conducted experiments seeking the origins of [[life]]. | ||

| − | + | He examined [[protozoa]], single-celled creatures with nuclei. He grew cultured [[Vesicle (biology)|vesicles]] using grass, sand, iron, and animal tissue, boiling them, and adding [[potassium]] and [[gelatin]]. Having heated the materials to [[incandescence]] with a heat-torch, he noted bright, glowing, blue vesicles, which, he said, could be cultured, and which gave off an observable radiant energy. This he called "orgone." He named the vesicles "bions" and believed they were a rudimentary form of life, or halfway between life and non-life.<ref name=bio/> | |

| − | |||

| − | He examined [[protozoa]], single-celled creatures with nuclei. He grew cultured [[Vesicle (biology)|vesicles]] using grass, sand, iron, and animal tissue, boiling them, and adding [[potassium]] and [[gelatin]]. Having heated the materials to [[incandescence]] with a heat-torch, he noted bright, glowing, blue vesicles, which, he said, could be cultured, and which gave off an observable radiant energy. This he called "orgone." He named the vesicles "bions" and believed they were a rudimentary form of life, or halfway between life and non-life. | ||

When he poured the cooled mixture onto growth media, [[bacteria]] were born. Based on various control experiments, Reich dismissed the idea that the bacteria were already present in the air, or in the other materials used. Reich's ''The Bion Experiments on the Origin of Life'' was published in Oslo in 1938, leading to attacks in the press that he was a "Jew pornographer" who was daring to meddle with the origins of life.<ref name=Cantwell/> | When he poured the cooled mixture onto growth media, [[bacteria]] were born. Based on various control experiments, Reich dismissed the idea that the bacteria were already present in the air, or in the other materials used. Reich's ''The Bion Experiments on the Origin of Life'' was published in Oslo in 1938, leading to attacks in the press that he was a "Jew pornographer" who was daring to meddle with the origins of life.<ref name=Cantwell/> | ||

===T-bacilli=== | ===T-bacilli=== | ||

| + | In 1936, in ''Beyond Psychology,'' Reich wrote that "[s]ince everything is antithetically arranged, there must be two different types of single-celled organisms: (a) life-destroying organisms or organisms that form through organic decay, (b) life-promoting organisms that form from inorganic material that comes to life."<ref> Wilhelm Reich and Mary Higgins, ''Beyond Psychology Letters and Journals, 1934-1939'' (New York, NY: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1994, ISBN 9780374112479).</ref> | ||

| − | + | This idea of [[spontaneous generation]] led him to believe he had found the cause of [[cancer]]. He called the life-destroying organisms "T-bacilli," with the T standing for ''Tod,'' German for [[death]]. He described in ''The Cancer Biopathy'' how he had found them in a culture of rotting cancerous tissue obtained from a local hospital. He wrote that T-bacilli were formed from the disintegration of [[protein]]; they were 0.2 to 0.5 micrometer in length, shaped like lancets, and when injected into mice, they caused inflammation and cancer. He concluded that, when orgone energy diminishes in cells through aging or injury, the cells undergo "bionous degeneration" or death. At some point, the deadly T-bacilli start to form in the cells. Death from cancer, he believed, was caused by an overwhelming growth of the T-bacilli. | |

| − | |||

| − | This idea of [[spontaneous generation]] led him to believe he had found the cause of cancer. He called the life-destroying organisms "T-bacilli," with the T standing for ''Tod'' | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | In 1940, Reich built boxes called ''orgone accumulators'' to concentrate atmospheric ''[[orgone|orgone energy]];'' some were for | + | ===Orgone accumulators=== |

| + | In 1940, Reich built boxes called ''orgone accumulators'' to concentrate atmospheric ''[[orgone|orgone energy]];'' some were for laboratory animals, and some were large enough for a human being to sit inside. Reich said orgone was the "primordial cosmic energy," blue in color, which he claimed was [[Omnipresence|omnipresent]] and responsible for such things as [[weather]], the color of the [[sky]], [[gravity]], the formation of which he believed that sitting inside the box might provide a treatment for [[cancer]] and other illnesses. Based on experiments with the orgone accumulator, he argued that orgone energy was a negatively-entropic force in nature which was responsible for concentrating and organizing matter. | ||

| − | Reich posited a conjugate, life-annulling energy in opposition to orgone, which he dubbed Deadly Orgone or DOR. Reich claimed that accumulations of DOR played a role in desertification and designed a "[[cloudbuster]]" with which he said he could manipulate streams of orgone energy in the atmosphere to induce rain by forcing clouds to form and disperse | + | Reich posited a conjugate, life-annulling energy in opposition to orgone, which he dubbed "Deadly Orgone" or DOR. Reich claimed that accumulations of DOR played a role in desertification and designed a "[[cloudbuster]]" with which he said he could manipulate streams of orgone energy in the atmosphere to induce rain by forcing clouds to form and disperse. |

| − | According to Reich's theory, illness was primarily caused by depletion or blockages of the orgone energy within the body. He conducted clinical tests of the orgone accumulator on people suffering from a variety of illnesses. The patient would sit within the accumulator and absorb the "concentrated orgone energy." He built smaller, more portable accumulator-blankets of the same layered construction for application to parts of the body. The effects observed were claimed to boost the [[immune system]], even to the point of destroying certain types of tumors, though Reich was hesitant to claim this constituted a "cure." The orgone accumulator was also tested on mice with cancer, and on plant-growth, the results convincing Reich that the benefits of orgone therapy could not be attributed to a [[placebo effect]]. He had, he believed, developed a grand unified theory of physical and mental health. | + | According to Reich's theory, illness was primarily caused by depletion or blockages of the orgone energy within the body. He conducted clinical tests of the orgone accumulator on people suffering from a variety of illnesses. The patient would sit within the accumulator and absorb the "concentrated orgone energy." He built smaller, more portable accumulator-blankets of the same layered construction for application to parts of the body. The effects observed were claimed to boost the [[immune system]], even to the point of destroying certain types of tumors, though Reich was hesitant to claim this constituted a "cure." The orgone accumulator was also tested on mice with cancer, and on plant-growth, the results convincing Reich that the benefits of orgone therapy could not be attributed to a [[placebo effect]]. He had, he believed, developed a grand unified theory of physical and mental health. |

| − | === | + | ===Einstein's test=== |

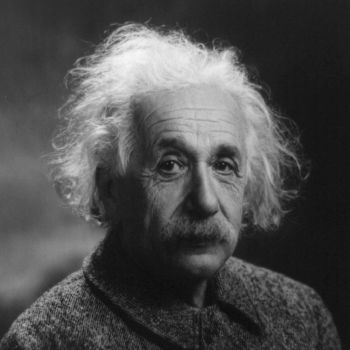

| + | [[Image:Albert Einstein Head.jpg||right|thumb|350px|Reich discussed orgone accumulators with [[Albert Einstein]] in 1941.]] | ||

| + | On December 30, 1940, Reich wrote to [[Albert Einstein]] saying he had a scientific discovery he wanted to discuss, and on January 13, 1941 went to visit [[Albert Einstein]] in [[Princeton, New Jersey|Princeton]]. They talked for five hours, and Einstein agreed to test an orgone accumulator, which Reich had constructed out of a [[Faraday cage]] made of galvanized steel and insulated by wood and paper on the outside.<ref name=Sharaf285>Sharaf, 285.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Reich supplied Einstein with a small accumulator during their second meeting, and Einstein performed the experiment in his basement, which involved taking the temperature atop, inside, and near the device. He also stripped the device down to its Faraday cage to compare temperatures. In his attempt to replicate Reich's findings, Einstein observed a rise in temperature,<ref name=Einstein7f> "I have now investigated your apparatus …. In the beginning I made enough readings without any changes in your arrangements. The box-thermometer showed regularly a temperature of about 0.3-0.4 higher then the one suspended freely," Einstein's letter to Reich, February 7th, 1941, English translation, in ''The Einstein Affair'' (Orgone Institute Press, 1953).</ref> which according to Reich was the result of a novel form of energy—orgone energy—that had accumulated inside the Faraday cage. However, one of Einstein's assistants pointed out that the temperature was lower at the floor than that on the ceiling<ref> "One of my assistants now drew my attention to the fact that in the room … the temperature on the floor is always lower than the one on the ceiling" Einstein to Reich, February 7th, 1941, </ref>. Following that remark, Einstein modified the experiment and, as a result, convinced himself that the effect was simply due to the temperature gradient inside the room<ref>"Through these experiments I regard the matter as completely solved." Einstein to Reich, February 7th, 1941</ref>. He then wrote back to Reich, describing his experiments and expressing the hope that Reich would develop a more skeptical approach. <ref>"Ich hoffe, dass dies Ihre Skepsis entwickeln wird" in Einstein to Reich, February 7th, 1941 In English "I hope that this will develop your skepticsm." This sentence is missing in the original English translation.</ref>. | |

| − | |||

| − | Reich | + | Reich responded with a 25-page letter to Einstein, expressing concern that "convection from the ceiling" would join "air germs" and "Brownian movement" to explain away new findings, according to Reich's biographer, Myron Sharaf. Sharaf wrote that Einstein conducted some more experiments, but then regarded the matter as "completely solved." |

| − | + | The correspondence between Reich and Einstein was published by Reich's press as ''The Einstein Affair'' in 1953, possibly without Einstein's permission.<ref name=Sharaf288>Sharaf, 288.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | The correspondence between Reich and Einstein was published by Reich's press as ''The Einstein Affair'' in 1953, possibly without Einstein's permission.<ref name=Sharaf288> | ||

==Controversy== | ==Controversy== | ||

| − | + | In 1947, following a series of critical articles about orgone in ''[[The New Republic]]'' and ''[[Harper's Magazine|Harper's]],'' the U.S. [[Food and Drug Administration]] (FDA) began an investigation into his claims, and won an injunction against the interstate sale of orgone accumulators. Charged with [[contempt of court]] for violating the injunction, Reich conducted his own defense, which involved sending the judge all his books to read.<ref name=bio/> He was sentenced to two years in [[prison]], and in August 1956, several tons of his [[Book burning|publications were burned]] by the FDA.<ref name=Cantwell/> He died of heart failure in jail just over a year later, days before he was due to apply for [[parole]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Reich's work | + | ==Legacy== |

| + | New research journals devoted to Reich's work began to appear in the 1960s. Physicians and natural scientists with an interest in Reich organized small study groups and institutes, and new research efforts were undertaken. James DeMeo undertook research at the [[University of Kansas]] into Reich's atmospheric theories.<ref>James DeMeo, "Preliminary Analysis of Changes in Kansas Weather Coincidental to Experimental Operations with a Reich Cloudbuster," (KU Geography-Meteorology Dept, Thesis, 1979).</ref> A later study by DeMeo subjected Reich's sex-economic theory to cross-cultural evaluations,<ref>James DeMeo, "On the Origins and Diffusion of Patrism: The Saharasian Connection," (KU Geography-Meteorology Dept, Dissertation, 1986).</ref> later included in DeMeo's opus magnum ''Saharasia.''<ref>James DeMeo, ''Saharasia: The 4000 B.C.E. Origins of Child Abuse, Sex-Repression, Warfare and Social Violence in the Deserts of the Old World. The Revolutionary Discovery of a Geographic Basis to Human Behavior'' (Ashland, OR: Natural Energy Works, 2006, ISBN 978-0962185557).</ref> | ||

| − | + | Reich's orgone research has not found an open reception; the mainstream scientific community remains largely uninterested in, and at times hostile to, his ideas. There is some use of orgone accumulator therapy by psychotherapists in Europe, particularly in Germany.<ref>For example: Jorgos Kavouras, "Heilen mit Orgonenergie: Die Medizinische Orgonomie," (Bietigheim, Germany: Turm Verlag, 2005); Heiko Lassek, "Orgon-Therapie: Heilen mit der reinen Lebensenergie," (München, Germany: Scherz Verlag, 1997); Stefan Müschenich, Der Gesundheitsbegriff im Werk des Arztes Wilhelm Reich (The Concept of Health in the Works of Wilhelm Reich, MD), med. Diss., (Marburg: Görich & Weiershauser, 1995)</ref> A double-blind, controlled study of the psychological and physical effects of the orgone accumulator was carried out by Stefan Müschenich and Rainer Gebauer at the [[Philipps University of Marburg|University of Marburg]] and appeared to validate some of Reich's claims.<ref>Stefan Müschenich and Rainer Gebauer, ''Der Reich'sche Orgonakkumulator: Naturwissenschaftliche Diskussion, praktische Anwendung, experimentelle Untersuchung'' (Frankfurt/Main: Nexus-Verlag 1987)</ref> The study was later reproduced by Günter Hebenstreit at the University of Vienna.<ref>Günter Hebenstreit, ''Der Orgonakkumulator nach Wilhelm Reich: Eine experimentelle Untersuchung zur Spannungs-Ladungs-Formel'' (Univ. Wien, Dipl.-Arbeit, 1995).</ref> [[William Steig]], [[Robert Anton Wilson]], [[Norman Mailer]], [[William S. Burroughs]], [[J. D. Salinger|Jerome D. Salinger]], and [[Orson Bean]] have all undergone Reich's orgone therapy. | |

| − | Reich | + | Reich's influence is felt in modern psychotherapy. He was a pioneer of [[body psychotherapy]] and several emotions-based psychotherapies, influencing [[Fritz Perls]]' [[Gestalt therapy]] and [[Arthur Janov]]'s [[primal therapy]]. His pupil [[Alexander Lowen]], the founder of [[bioenergetic analysis]], [[Charles Kelley]], the founder of [[Radix therapy]], and James DeMeo ensure that his research receives widespread attention. Many practicing psychoanalysts give credence to his theory of character, as outlined in his book ''Character Analysis'' (1933, enlarged 1949). The [[American College of Orgonomy]] founded by the late Elsworth Baker M.D.,<ref>[https://www.orgonomy.org/ The American College of Orgonomy] Retrieved November 17, 2023.</ref> and the Institute for Orgonomic Science led by Dr. Morton Herskowitz,<ref>[https://orgonomicscience.org/ Institute for Orgonomic Science]. Retrieved November 17, 2023.</ref> still use Reich's original therapeutic methods. |

| + | Nearly all Reich's publications have been reprinted, apart from his research journals which are available as photocopies from the Wilhelm Reich Museum. The first editions are not available: Reich continuously amended his books throughout his life, and the owners of Reich's [[intellectual property]] actively forbid anything other than the latest revised versions to be reprinted. In the late 1960s, Farrar, Straus & Giroux republished Reich's major works. Reich's earlier books, particularly ''The Mass Psychology of Fascism,'' are regarded as historically valuable. A good overview of Reich's work is ''Wilhelm Reich: The Evolution of his work,'' by David Boadella.<ref>David Boadella, ''Wilhelm Reich, The Evolution of His Work'' (New York, NY: Viking Press, 1988, ISBN 978-0140190700).</ref> A bibliography on orgonomy gives full citations to university dissertations, and to controlled experiments replicating Reich's work on bions, the orgone accumulator, and the cloudbuster.<ref>[http://www.orgonelab.org/bibliog.htm Bibliography on Orgonomy]. Retrieved November 17, 2023.</ref> | ||

| + | Reich's life and work continue to influence popular culture, with references to orgone and cloudbusting to be found in a variety of songs and other media. | ||

| − | ==Major | + | ==Major publications== |

| − | + | * ''Mass Psychology of Fascism'' (translation of the revised and enlarged version of ''Massenpsychologie des Faschismus'' from 1933). (1946). New York: Orgone Inst. Press. {{OCLC|179767946}} | |

| − | + | * ''Listen, Little Man!'' (1948). London: Souvenir Press (Educational) & Academic. {{OCLC|81625045}} | |

| − | *'' | + | * ''The function of the orgasm: sex-economic problems of biological energy.'' [1948] 1973. New York: Pocket Books. {{OCLC|1838547}} |

| − | + | * ''The Cancer Biopathy'' (1948). New York: Orgone Institute Press. {{OCLC|11132152}} | |

| − | *'' | + | * ''Ether, God and Devil'' (1949). New York: Orgone Institute Press. {{OCLC|9801512}} |

| − | + | * ''Character Analysis'' (translation of the enlarged version of ''Charakteranalyse'' from 1933). [1949] 1972. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0374120749 | |

| − | *'' | + | * ''Cosmic Superimposition: Man's Orgonotic Roots in Nature'' (1951). Rangeley, ME: Wilhelm Reich Foundation. {{OCLC|2939830}} |

| − | *'' | + | * ''The Sexual Revolution'' (translation of ''Die Sexualität im Kulturkampf'' from 1936). (1951). London, UK: Peter Nevill: Vision Press. {{OCLC|10011610}} |

| − | *'' | + | * ''The Orgone Energy Accumulator, Its Scientific and Medical Use'' (1951). Rangeley, ME: Orgone Institute Press. {{OCLC|14672260}} |

| − | *'' | + | * ''The Oranur Experiment'' [1951]. Rangeley, ME: Wilhelm Reich Foundation. {{OCLC|8503708}} |

| − | + | * ''The murder of Christ volume one of the emotional plague of mankind''. [1953] 1976. New York: Pocket Books. ISBN 0671804146 | |

| − | *'' | + | * ''People in Trouble'' (1953). Orgonon, Rangely, ME: Orgonon Institute Press. {{OCLC|21352304}} |

| − | *'' | + | * ''History of the discovery of the life energy; the Einstein affair.'' (1953) The Orgone Institute. {{OCLC|2147629}} |

| − | + | * ''Contact With Space: Oranur Second Report.'' (1957). New York: Core Pilot Press. {{OCLC|4481512}} | |

| − | + | * ''Selected Writings: An Introduction to Orgonomy.'' [1960]. New York: Farrar, Straus and Cudahy. {{OCLC|14617786}} | |

| − | + | * ''Reich Speaks of Freud'' (Interview by Kurt R. Eissler, letters, documents). [1967] 1975. Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 0140218580 | |

| − | * '' | + | * ''The Invasion of Compulsory Sex-Morality'' (translation of the revised and enlarged version of ''Der Eindruch der Sexualmoral'' from 1932). (1972). London: Souvenir Press. ISBN 0285647032 |

| − | * ''The | + | * ''The Bion Experiments on the Origins of Life.'' (1979). New York: Octagon Books. {{OCLC|4491743}} |

| − | * ''The | + | * ''Genitality in the Theory and Therapy of Neuroses'' (translation of the original, unrevised version of ''Die Funktion des Orgasmus'' from 1927). (1980). New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux. ISBN 0374161127 |

| − | + | * ''Record of a Friendship: The Correspondence of Wilhelm Reich and A.S. Neill (1936-1957).'' (1981). New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux. ISBN 0374248079 | |

| − | * '' | + | * ''The Bioelectrical Investigation of Sexuality and Anxiety.'' (1982). New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. {{OCLC|7464279}} |

| − | * '' | + | * ''Children of the Future: On the Prevention of Sexual Pathology''. (1983). New York: Farrar Straus Giroux. ISBN 0374121737 |

| − | + | * ''Passion of Youth: An Autobiography, 1897-1922''. (1988) (posthumous). New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux. ISBN 9780374229955 | |

| − | * ''Contact With Space: Oranur Second Report'' (1957) | + | * ''Beyond Psychology: Letters and Journals 1934-1939'' (posthumous). (1994). New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 0374112479 |

| − | + | * ''American Odyssey: Letters and Journals 1940-1947'' (posthumous). (1999). New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0374104360 | |

| − | * '' | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * '' | ||

| − | * ''The Invasion of Compulsory Sex-Morality'' (translation of the revised and enlarged version of ''Der Eindruch der Sexualmoral'' from 1932) | ||

| − | * '' | ||

| − | * '' | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * ''Record of a Friendship: The Correspondence of Wilhelm Reich and A.S. Neill (1936-1957)'' | ||

| − | * '' | ||

| − | * '' | ||

| − | * '' | ||

| − | * '' | ||

| − | * '' | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| − | + | <references/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==References == | |

| − | * | + | * Baker, Elsworth F. ''Man In The Trap'', The American College of Orgonomy Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0967967004 |

| − | * | + | * Bean, Orson. ''Me And The Orgone'', American College of Orgonomy Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0967967011 |

| − | *Brian, Denis. ''Einstein: A Life'', John Wiley & Sons | + | * Boadella, David. ''Wilhelm Reich, The Evolution Of His Work'', New York, NY: Viking Press, 1988. ISBN 978-0140190700 |

| − | *Clark, Ronald W. ''Einstein: The Life and Times'', New York: Avon, 1971, ISBN | + | * Boadella, David. (Ed.): ''In The Wake Of Reich'', Ashley Books, 1977. ISBN 978-0879491031 |

| − | * | + | * Brian, Denis. ''Einstein: A Life'', New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, 1996. ISBN 0471114596 |

| − | * | + | * Clark, Ronald W. ''Einstein: The Life and Times'', New York, NY: Avon, 1971, ISBN 038001159X |

| − | * | + | * Corrington, Robert S. ''Wilhelm Reich: Psychoanalyst and Radical Naturalist'', New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003. ISBN 0374250022 |

| − | * | + | * DeMeo, James. ''The Orgone Accumulator Handbook: Construction Plans, Experimental Use and Protection Against Toxic Energy'', Ashland, OR: Natural Energy Works, 1989. ISBN 978-0962185502 |

| − | * | + | * DeMeo, James. ''Saharasia: The 4000 B.C.E. Origins of Child-Abuse, Sex-Repression, Warfare and Social Violence, In the Deserts of the Old World''. Ashland, OR: Natural Energy Works, 2006. ISBN 978-0962185557 |

| + | * DeMeo, James (ed.). ''Heretic's Notebook: Emotions, Protocells, Ether-Drift and Cosmic Life Energy, With New Research Supporting Wilhelm Reich'', Ashland, OR: Natural Energy Works, 2002. ISBN 978-0962185588 | ||

| + | * Herskowitz, Morton. ''Emotional Armoring: An Introduction to Psychiatric Orgone Therapy'', Transactions Press, NY 1998. ISBN 978-3825835552 | ||

| + | * Martin, Jim. ''Wilhelm Reich and the Cold War'', Mendocino, CA: Flatland Books, 2000. ISBN 1878124099 | ||

| + | * Raknes, Ola. ''Wilhelm Reich And Orgonomy'', American College of Orgonomy Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0967967028 | ||

| + | * Reich, Peter. ''A Book Of Dreams'', Dutton Obelisk, 1989. ISBN 978-0525484158 | ||

| + | * Sharaf, Myron. ''Fury on Earth: A Biography of Wilhelm Reich'', Da Capo, 1994. ISBN 978-0306805752 | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved November 17, 2023. | |

| − | + | *[https://www.aetherometry.com/ Aetherometry] | |

| − | + | *[https://www.orgone.org/ Orgone] | |

| − | *[ | + | *[http://www.orgonelab.org/ Orgone Biophysical Research Lab] James DeMeo's Research Website |

| − | *[ | + | *[https://skepdic.com/orgone.html orgone energy] ''Skeptic's Dictionary'' |

| − | *[http://www.orgonelab.org/ | + | *[http://www.orgonelab.org/gardner.htm Response to Martin Gardner] ''Orgone Biophysical Research Lab'' |

| − | + | *[https://orgonomy.org/ American College of Orgonomy] | |

| − | + | *[https://www.datadiwan.de/magazin/index_e.htm?/magazin/dz0100e_.htm Focal Point: Life Energy] ''Diwan Magazine'' | |

| − | *[ | + | *[http://www.rogermwilcox.com/Reich/ A Skeptical Scrutiny of the Works and Theories of Wilhelm Reich] By Roger M. Wilcox |

| − | *[http://www.orgonelab.org/gardner.htm Response to Martin Gardner' | + | *[http://www.marxist.com/marxism-psychoanalysis-wilhelm-reich.htm Marxism and Psychoanalysis: Notes on Wilhelm Reich's life and work] |

| − | *[ | ||

| − | *[ | ||

| − | *[http://www.rogermwilcox. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | *[http://www.marxist.com/ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

* [http://www.wilhelm-reich-akademie.de/ Wilhelm Reich Akademie] | * [http://www.wilhelm-reich-akademie.de/ Wilhelm Reich Akademie] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Credits|Wilhelm_Reich|157187966|}} | {{Credits|Wilhelm_Reich|157187966|}} | ||

Latest revision as of 20:11, 17 November 2023

| Wilhelm Reich | |

Portrait by Ludwig Gutmann Vienna, before 1943

| |

| Born | March 24 1897 Dobzau, Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, Austria-Hungary (now Dobrianychi, Lviv Oblast, Ukraine) |

|---|---|

| Died | November 3 1957 (aged 60) United States Penitentiary, Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Resting place | Orgonon, Rangeley, Maine, U.S. |

| Nationality | Austrian |

| Education | University of Vienna (MD, 1922) |

| Known for | Character analysis muscular armour orgastic potency vegetotherapy Freudo-Marxism orgone |

| Partner(s) |

|

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Robert Reich (brother) |

Wilhelm Reich (March 24, 1897 – November 3, 1957) was an Austrian-American psychiatrist and psychoanalyst. He was a respected analyst for much of his life, focusing on character structure, rather than on individual neurotic symptoms. He promoted adolescent sexuality, the availability of contraceptives and abortion, and the importance for women of economic independence. Reich's work influenced thinkers such as Alexander Lowen, Fritz Perls, Paul Goodman, Saul Bellow, Norman Mailer, and William Burroughs. His work synthesized material from psychoanalysis, cultural anthropology, economics, sociology, and ethics.

Reich became a controversial figure for his studies on the link between human sexuality and neuroses, emphasizing "orgastic potency" as the foremost criterion for psycho-physical health. He said he had discovered a form of energy that permeated the atmosphere and all living matter, which he called "orgone." He built boxes called "orgone accumulators," which patients could sit inside, and which were intended to harness the energy for what he believed were its health benefits. It was this work, in particular, that cemented the rift between Reich and the psychiatric establishment. His experiments and commercialization of the orgone box brought Reich into conflict with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, leading to a lawsuit, conviction, and incarceration. He died in prison.

Although Reich's early work was overshadowed by the controversy and loss of credibility of his later work, his influence has been significant. While his ideas may have strained the limits of scientific respectability, as well as morality, Reich's desire and efforts were for the betterment of humankind. His realization that sexual energy is potent rings true; it is harnessing that energy successfully in a moral and ethical manner that is the challenge, one in which Reich did not find the correct answer.

Life

Wilhelm Reich was born in 1897 to Leon Reich, a prosperous farmer, and Cecilia Roniger, in Dobrzanica,[1] a village in Galicia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Three years after his birth, the couple had a second son, Robert.

His father was by all accounts strict, cold, and jealous. He was Jewish, but Reich was later at pains to point out that his father had moved away from Judaism and had not raised his children as Jews; Reich was not allowed to play with Yiddish-speaking children,[2] and as an adult did not want to be described as Jewish.[3]

Shortly after his birth, the family moved south to a farm in Jujinetz, near Chernivtsi, Bukovina, where Reich's father took control of a cattle farm owned by his mother's family. Reich attributed his later interest in the study of sexuality and the biological basis of the emotions to his upbringing on the farm where, as he later put it, the "natural life functions" were never hidden from him.[4]

He was taught at home until he was 12, when his mother committed suicide after being discovered by her husband of having an affair with Reich's tutor, who lived with the family. He wrote that his "joy of life [was] shattered, torn apart from [his] inmost being for the rest of [his] life!"[5]

The tutor was sent away, and Reich was left without his mother or his teacher, and with a powerful sense of guilt.[6] He was sent to the all-male Czernowitz gymnasium, excelling at Latin, Greek, and the natural sciences.

Reich's father was "completely broken" by his wife's suicide.[7] He contracted pneumonia and then tuberculosis, and died in 1914 as a result of his illness; despite his insurance policy, no money was forthcoming.

Reich managed the farm and continued with his studies, graduating in 1915 mit Stimmeneinhelligkeit (unanimous approval). In the summer of 1915, the Russians invaded Bukovina and the Reich brothers fled to Vienna, losing everything. In his Passion of Youth, Reich wrote: "I never saw either my homeland or my possessions again. Of a well-to-do past, nothing was left."[8]

Reich joined the Austrian Army after school, serving from 1915-1918, for the last two years as a lieutenant.

In 1918, when the war ended, he entered the medical school at the University of Vienna. As an undergraduate, he was drawn to the work of Sigmund Freud; the men first met in 1919 when Reich visited Freud to obtain literature for a seminar on sexology. Freud left a strong impression on Reich. Freud allowed him to start seeing analytic patients as early as 1920. Reich was accepted as a guest member of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Association in the summer of 1920, and became a regular member in October 1920, at the age of 23.[9] Reich's brilliance as an analyst and author of numerous important articles on psychoanalysis caused Freud to select him as a first assistant physician when Freud organized the Psychoanalytic-Polyclinic in Vienna in 1922. It was at the Vienna Psychoanalytic Association that Reich met Annie Pink, a patient of his and later an analyst herself.[10] They married and had two daughters, Eva in 1924[11] and Lore in 1928.[12] The couple separated in 1933, leaving the children with their mother.

Reich was allowed to complete his six-year medical degree in four years because he was a war veteran, and received his M.D. in July 1922.[8]

Reich was very outspoken about Germany’s turbulent political climate. Unlike most members of the Berlin Psychoanalytic Association, Reich openly opposed the rise of the Nazi Party. In 1933 he was denounced by the Communist Party, forced to flee from Germany when Hitler came to power, and expelled from the International Psychoanalytic Association in 1934.

Reich was invited to teach at the New School for Social Research in New York City and on August 19, 1939 Reich sailed for America on the last ship to leave Norway before World War II broke out. Reich settled in the Forest Hills section of New York City and in 1946, married Ilse Ollendorf, with whom he had a son, Peter.

Reich died in his sleep of heart failure on November 3, 1957 in the federal penitentiary in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania.

His work

Early career

He worked in internal medicine at University Hospital, Vienna, and studied neuropsychiatry from 1922-1924 at the Neurological and Psychiatric Clinic under Professor Wagner-Jauregg, who won the Nobel Prize in medicine in 1927.

In 1922, he set up private practice as a psychoanalyst, and became a clinical assistant, and later deputy director, at Sigmund Freud's Psychoanalytic Polyclinic. He joined the faculty of the Psychoanalytic Institute in Vienna in 1924, and conducted research into the social causes of neurosis. Reich's second wife, Elsa Lindenburg, was trained in Laban movement analysis, and was a pupil of Elsa Gindler, who had started to develop a system of breathing and somatic responsiveness named Arbeit am Menschen in 1910. Reich first presented the principles of his vegetotherapy in a paper on "Psychic contact and vegetative current" in August 1934 at the 13th International Congress of Psychoanalysis at Lucerne, Switzerland, and went on to develop the technique between 1935 and 1940.

Reich developed a theory that the ability to feel sexual love depended on a physical ability to make love with what he called "orgastic potency." He attempted to measure the male orgasm, noting that four distinct phases occurred physiologically: first, the psychosexual build-up or tension; second, the tumescence of the penis, with an accompanying "charge," which Reich measured electrically; third, an electrical discharge at the moment of orgasm; and fourth, the relaxation of the penis. He believed the force that he measured was a distinct type of energy present in all life forms and later called it "orgone."[13]

He was a prolific writer for psychoanalytic journals in Europe. Originally, psychoanalysis was focused on the treatment of neurotic symptoms. Reich's Character Analysis was a major step in the development of what today would be called "ego psychology." In Reich's view, a person's entire character, not only individual symptoms, could be looked at and treated as a neurotic phenomenon. The book also introduced Reich's theory of "body armoring." He argued that unreleased psychosexual energy could produce actual physical blocks within muscles and organs, and that these act as a "body armor," preventing the release of the energy. An orgasm was one way to break through the armor. These ideas developed into a general theory of the importance of a healthy sex life to overall well-being, a theory compatible with Freud's views.

Reich agreed with Freud that sexual development was the origin of mental disorder. They both believed that most psychological states were dictated by unconscious processes; that infant sexuality develops early but is repressed, and that this has important consequences for mental health. At that time a Marxist, Reich argued that the source of sexual repression was bourgeois morality and the socio-economic structures that produced it. As sexual repression was the cause of the neuroses, the best cure would be to have an active, guilt-free sex life. He argued that such a liberation could come about only through a morality not imposed by a repressive economic structure.[14] In 1928, he joined the Austrian Communist Party and founded the Socialist Association for Sexual Counselling and Research, which organized counseling centers for workers — in contrast to Freud, who was perceived as treating only the bourgeoisie.

Reich employed an unusual therapeutic method. He used touch to accompany the talking cure, taking an active role in sessions, feeling his patients' chests to check their breathing, repositioning their bodies, and sometimes requiring them to remove their clothes, treating them in their underwear. These methods caused a split between Reich and the rest of the psychoanalytic community.[13]

In 1930, he moved his practice to Berlin and joined the Communist Party of Germany. His best-known book, The Sexual Revolution, was published at this time in Vienna. Advocating free contraceptives and abortion on demand, he again set up clinics in working-class areas and taught sex education, but became too outspoken even for the communists, and eventually, after his book The Mass Psychology of Fascism was published, he was expelled from the party in 1933.

In this book, Reich categorized fascism as a symptom of sexual repression. The book was banned by the Nazis when they came to power. He realized he was in danger and hurriedly left Germany disguised as a tourist on a ski trip to Austria. Reich was expelled from the International Psychological Association in 1934 for political militancy. According to his daughter Lore, Anna Freud and Ernest Jones were behind the expulsion of Reich.[15] He spent some years in Denmark, Sweden, and Norway, before leaving for the United States in 1939.

The bion experiments

From 1934-1937, based for most of the period in Oslo, Reich conducted experiments seeking the origins of life.

He examined protozoa, single-celled creatures with nuclei. He grew cultured vesicles using grass, sand, iron, and animal tissue, boiling them, and adding potassium and gelatin. Having heated the materials to incandescence with a heat-torch, he noted bright, glowing, blue vesicles, which, he said, could be cultured, and which gave off an observable radiant energy. This he called "orgone." He named the vesicles "bions" and believed they were a rudimentary form of life, or halfway between life and non-life.[8]

When he poured the cooled mixture onto growth media, bacteria were born. Based on various control experiments, Reich dismissed the idea that the bacteria were already present in the air, or in the other materials used. Reich's The Bion Experiments on the Origin of Life was published in Oslo in 1938, leading to attacks in the press that he was a "Jew pornographer" who was daring to meddle with the origins of life.[13]

T-bacilli

In 1936, in Beyond Psychology, Reich wrote that "[s]ince everything is antithetically arranged, there must be two different types of single-celled organisms: (a) life-destroying organisms or organisms that form through organic decay, (b) life-promoting organisms that form from inorganic material that comes to life."[16]

This idea of spontaneous generation led him to believe he had found the cause of cancer. He called the life-destroying organisms "T-bacilli," with the T standing for Tod, German for death. He described in The Cancer Biopathy how he had found them in a culture of rotting cancerous tissue obtained from a local hospital. He wrote that T-bacilli were formed from the disintegration of protein; they were 0.2 to 0.5 micrometer in length, shaped like lancets, and when injected into mice, they caused inflammation and cancer. He concluded that, when orgone energy diminishes in cells through aging or injury, the cells undergo "bionous degeneration" or death. At some point, the deadly T-bacilli start to form in the cells. Death from cancer, he believed, was caused by an overwhelming growth of the T-bacilli.

Orgone accumulators

In 1940, Reich built boxes called orgone accumulators to concentrate atmospheric orgone energy; some were for laboratory animals, and some were large enough for a human being to sit inside. Reich said orgone was the "primordial cosmic energy," blue in color, which he claimed was omnipresent and responsible for such things as weather, the color of the sky, gravity, the formation of which he believed that sitting inside the box might provide a treatment for cancer and other illnesses. Based on experiments with the orgone accumulator, he argued that orgone energy was a negatively-entropic force in nature which was responsible for concentrating and organizing matter.

Reich posited a conjugate, life-annulling energy in opposition to orgone, which he dubbed "Deadly Orgone" or DOR. Reich claimed that accumulations of DOR played a role in desertification and designed a "cloudbuster" with which he said he could manipulate streams of orgone energy in the atmosphere to induce rain by forcing clouds to form and disperse.

According to Reich's theory, illness was primarily caused by depletion or blockages of the orgone energy within the body. He conducted clinical tests of the orgone accumulator on people suffering from a variety of illnesses. The patient would sit within the accumulator and absorb the "concentrated orgone energy." He built smaller, more portable accumulator-blankets of the same layered construction for application to parts of the body. The effects observed were claimed to boost the immune system, even to the point of destroying certain types of tumors, though Reich was hesitant to claim this constituted a "cure." The orgone accumulator was also tested on mice with cancer, and on plant-growth, the results convincing Reich that the benefits of orgone therapy could not be attributed to a placebo effect. He had, he believed, developed a grand unified theory of physical and mental health.

Einstein's test

On December 30, 1940, Reich wrote to Albert Einstein saying he had a scientific discovery he wanted to discuss, and on January 13, 1941 went to visit Albert Einstein in Princeton. They talked for five hours, and Einstein agreed to test an orgone accumulator, which Reich had constructed out of a Faraday cage made of galvanized steel and insulated by wood and paper on the outside.[17]

Reich supplied Einstein with a small accumulator during their second meeting, and Einstein performed the experiment in his basement, which involved taking the temperature atop, inside, and near the device. He also stripped the device down to its Faraday cage to compare temperatures. In his attempt to replicate Reich's findings, Einstein observed a rise in temperature,[18] which according to Reich was the result of a novel form of energy—orgone energy—that had accumulated inside the Faraday cage. However, one of Einstein's assistants pointed out that the temperature was lower at the floor than that on the ceiling[19]. Following that remark, Einstein modified the experiment and, as a result, convinced himself that the effect was simply due to the temperature gradient inside the room[20]. He then wrote back to Reich, describing his experiments and expressing the hope that Reich would develop a more skeptical approach. [21].

Reich responded with a 25-page letter to Einstein, expressing concern that "convection from the ceiling" would join "air germs" and "Brownian movement" to explain away new findings, according to Reich's biographer, Myron Sharaf. Sharaf wrote that Einstein conducted some more experiments, but then regarded the matter as "completely solved."

The correspondence between Reich and Einstein was published by Reich's press as The Einstein Affair in 1953, possibly without Einstein's permission.[22]

Controversy

In 1947, following a series of critical articles about orgone in The New Republic and Harper's, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) began an investigation into his claims, and won an injunction against the interstate sale of orgone accumulators. Charged with contempt of court for violating the injunction, Reich conducted his own defense, which involved sending the judge all his books to read.[8] He was sentenced to two years in prison, and in August 1956, several tons of his publications were burned by the FDA.[13] He died of heart failure in jail just over a year later, days before he was due to apply for parole.

Legacy

New research journals devoted to Reich's work began to appear in the 1960s. Physicians and natural scientists with an interest in Reich organized small study groups and institutes, and new research efforts were undertaken. James DeMeo undertook research at the University of Kansas into Reich's atmospheric theories.[23] A later study by DeMeo subjected Reich's sex-economic theory to cross-cultural evaluations,[24] later included in DeMeo's opus magnum Saharasia.[25]

Reich's orgone research has not found an open reception; the mainstream scientific community remains largely uninterested in, and at times hostile to, his ideas. There is some use of orgone accumulator therapy by psychotherapists in Europe, particularly in Germany.[26] A double-blind, controlled study of the psychological and physical effects of the orgone accumulator was carried out by Stefan Müschenich and Rainer Gebauer at the University of Marburg and appeared to validate some of Reich's claims.[27] The study was later reproduced by Günter Hebenstreit at the University of Vienna.[28] William Steig, Robert Anton Wilson, Norman Mailer, William S. Burroughs, Jerome D. Salinger, and Orson Bean have all undergone Reich's orgone therapy.

Reich's influence is felt in modern psychotherapy. He was a pioneer of body psychotherapy and several emotions-based psychotherapies, influencing Fritz Perls' Gestalt therapy and Arthur Janov's primal therapy. His pupil Alexander Lowen, the founder of bioenergetic analysis, Charles Kelley, the founder of Radix therapy, and James DeMeo ensure that his research receives widespread attention. Many practicing psychoanalysts give credence to his theory of character, as outlined in his book Character Analysis (1933, enlarged 1949). The American College of Orgonomy founded by the late Elsworth Baker M.D.,[29] and the Institute for Orgonomic Science led by Dr. Morton Herskowitz,[30] still use Reich's original therapeutic methods.

Nearly all Reich's publications have been reprinted, apart from his research journals which are available as photocopies from the Wilhelm Reich Museum. The first editions are not available: Reich continuously amended his books throughout his life, and the owners of Reich's intellectual property actively forbid anything other than the latest revised versions to be reprinted. In the late 1960s, Farrar, Straus & Giroux republished Reich's major works. Reich's earlier books, particularly The Mass Psychology of Fascism, are regarded as historically valuable. A good overview of Reich's work is Wilhelm Reich: The Evolution of his work, by David Boadella.[31] A bibliography on orgonomy gives full citations to university dissertations, and to controlled experiments replicating Reich's work on bions, the orgone accumulator, and the cloudbuster.[32]

Reich's life and work continue to influence popular culture, with references to orgone and cloudbusting to be found in a variety of songs and other media.

Major publications

- Mass Psychology of Fascism (translation of the revised and enlarged version of Massenpsychologie des Faschismus from 1933). (1946). New York: Orgone Inst. Press. OCLC 179767946

- Listen, Little Man! (1948). London: Souvenir Press (Educational) & Academic. OCLC 81625045

- The function of the orgasm: sex-economic problems of biological energy. [1948] 1973. New York: Pocket Books. OCLC 1838547

- The Cancer Biopathy (1948). New York: Orgone Institute Press. OCLC 11132152

- Ether, God and Devil (1949). New York: Orgone Institute Press. OCLC 9801512

- Character Analysis (translation of the enlarged version of Charakteranalyse from 1933). [1949] 1972. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0374120749

- Cosmic Superimposition: Man's Orgonotic Roots in Nature (1951). Rangeley, ME: Wilhelm Reich Foundation. OCLC 2939830

- The Sexual Revolution (translation of Die Sexualität im Kulturkampf from 1936). (1951). London, UK: Peter Nevill: Vision Press. OCLC 10011610

- The Orgone Energy Accumulator, Its Scientific and Medical Use (1951). Rangeley, ME: Orgone Institute Press. OCLC 14672260

- The Oranur Experiment [1951]. Rangeley, ME: Wilhelm Reich Foundation. OCLC 8503708

- The murder of Christ volume one of the emotional plague of mankind. [1953] 1976. New York: Pocket Books. ISBN 0671804146

- People in Trouble (1953). Orgonon, Rangely, ME: Orgonon Institute Press. OCLC 21352304

- History of the discovery of the life energy; the Einstein affair. (1953) The Orgone Institute. OCLC 2147629

- Contact With Space: Oranur Second Report. (1957). New York: Core Pilot Press. OCLC 4481512

- Selected Writings: An Introduction to Orgonomy. [1960]. New York: Farrar, Straus and Cudahy. OCLC 14617786

- Reich Speaks of Freud (Interview by Kurt R. Eissler, letters, documents). [1967] 1975. Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 0140218580

- The Invasion of Compulsory Sex-Morality (translation of the revised and enlarged version of Der Eindruch der Sexualmoral from 1932). (1972). London: Souvenir Press. ISBN 0285647032

- The Bion Experiments on the Origins of Life. (1979). New York: Octagon Books. OCLC 4491743

- Genitality in the Theory and Therapy of Neuroses (translation of the original, unrevised version of Die Funktion des Orgasmus from 1927). (1980). New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux. ISBN 0374161127

- Record of a Friendship: The Correspondence of Wilhelm Reich and A.S. Neill (1936-1957). (1981). New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux. ISBN 0374248079

- The Bioelectrical Investigation of Sexuality and Anxiety. (1982). New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. OCLC 7464279

- Children of the Future: On the Prevention of Sexual Pathology. (1983). New York: Farrar Straus Giroux. ISBN 0374121737

- Passion of Youth: An Autobiography, 1897-1922. (1988) (posthumous). New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux. ISBN 9780374229955

- Beyond Psychology: Letters and Journals 1934-1939 (posthumous). (1994). New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 0374112479

- American Odyssey: Letters and Journals 1940-1947 (posthumous). (1999). New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0374104360

Notes

- ↑ Also written as Dobryanichi or 'Dobrjanici (in Ukrainian: Добряничі), village near Peremyshliany, now in Ukraine

- ↑ Myron Sharaf, Fury on Earth: A Biography of Wilhelm Reich (New York: Da Capo Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0306805752), 39.

- ↑ Sharaf, 463.

- ↑ Wilhelm Reich, "Background and scientific development of Wilhelm Reich," Orgone Energy Bulletin V (1953): 6, cited in Sharaf 1994, 40, 488, footnote 10.

- ↑ Wilhelm Reich, "Ueber einen Fall von Durchbruch der Inzestschranke in der Pubertät," Zeitschrift für Sexualwissenschaft, VII, (1920): 222-223, cited in and translated by Sharaf, 43 and 448, footnote 12.

- ↑ Sharaf, 42-46.

- ↑ Wilhelm Reich, "Ueber einen Fall von Durchbruch der Inzestschranke in der Pubertät," cited in Sharaf, 489, footnote 21.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Biography The Wilhelm Reich Museum. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ↑ Sharaf, 58.

- ↑ Edith Jacobsen, Annie Reich (1902-1971) International Journal of Psychoanalysis 52 (1971): 334-336. Retrieved Novemebr 17, 2023.

- ↑ Eva Reich became a doctor and applied orgonomical techniques to the care of newborns.

- ↑ Lore Reich Rubin became a doctor and psychoanalyst.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Alan Cantwell, Dr. Wilhelm Reich: Scientific Genuis or Medical Madman? New Dawn 84 (May–June 2004). Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ↑ Alessandro D'Aloia, Marxism and Psychoanalysis: Notes on Wilhelm Reich’s Life and Works Marxist.com. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ↑ Lore Reich, Wilhelm Reich and Anna Freud: His Expulsion from Psychoanalysis International Forum of Psychoanalysis 12(2-3) (2003):109-117. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ↑ Wilhelm Reich and Mary Higgins, Beyond Psychology Letters and Journals, 1934-1939 (New York, NY: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1994, ISBN 9780374112479).

- ↑ Sharaf, 285.

- ↑ "I have now investigated your apparatus …. In the beginning I made enough readings without any changes in your arrangements. The box-thermometer showed regularly a temperature of about 0.3-0.4 higher then the one suspended freely," Einstein's letter to Reich, February 7th, 1941, English translation, in The Einstein Affair (Orgone Institute Press, 1953).

- ↑ "One of my assistants now drew my attention to the fact that in the room … the temperature on the floor is always lower than the one on the ceiling" Einstein to Reich, February 7th, 1941,

- ↑ "Through these experiments I regard the matter as completely solved." Einstein to Reich, February 7th, 1941

- ↑ "Ich hoffe, dass dies Ihre Skepsis entwickeln wird" in Einstein to Reich, February 7th, 1941 In English "I hope that this will develop your skepticsm." This sentence is missing in the original English translation.

- ↑ Sharaf, 288.

- ↑ James DeMeo, "Preliminary Analysis of Changes in Kansas Weather Coincidental to Experimental Operations with a Reich Cloudbuster," (KU Geography-Meteorology Dept, Thesis, 1979).

- ↑ James DeMeo, "On the Origins and Diffusion of Patrism: The Saharasian Connection," (KU Geography-Meteorology Dept, Dissertation, 1986).

- ↑ James DeMeo, Saharasia: The 4000 B.C.E. Origins of Child Abuse, Sex-Repression, Warfare and Social Violence in the Deserts of the Old World. The Revolutionary Discovery of a Geographic Basis to Human Behavior (Ashland, OR: Natural Energy Works, 2006, ISBN 978-0962185557).

- ↑ For example: Jorgos Kavouras, "Heilen mit Orgonenergie: Die Medizinische Orgonomie," (Bietigheim, Germany: Turm Verlag, 2005); Heiko Lassek, "Orgon-Therapie: Heilen mit der reinen Lebensenergie," (München, Germany: Scherz Verlag, 1997); Stefan Müschenich, Der Gesundheitsbegriff im Werk des Arztes Wilhelm Reich (The Concept of Health in the Works of Wilhelm Reich, MD), med. Diss., (Marburg: Görich & Weiershauser, 1995)

- ↑ Stefan Müschenich and Rainer Gebauer, Der Reich'sche Orgonakkumulator: Naturwissenschaftliche Diskussion, praktische Anwendung, experimentelle Untersuchung (Frankfurt/Main: Nexus-Verlag 1987)

- ↑ Günter Hebenstreit, Der Orgonakkumulator nach Wilhelm Reich: Eine experimentelle Untersuchung zur Spannungs-Ladungs-Formel (Univ. Wien, Dipl.-Arbeit, 1995).

- ↑ The American College of Orgonomy Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ↑ Institute for Orgonomic Science. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ↑ David Boadella, Wilhelm Reich, The Evolution of His Work (New York, NY: Viking Press, 1988, ISBN 978-0140190700).

- ↑ Bibliography on Orgonomy. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Baker, Elsworth F. Man In The Trap, The American College of Orgonomy Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0967967004

- Bean, Orson. Me And The Orgone, American College of Orgonomy Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0967967011

- Boadella, David. Wilhelm Reich, The Evolution Of His Work, New York, NY: Viking Press, 1988. ISBN 978-0140190700

- Boadella, David. (Ed.): In The Wake Of Reich, Ashley Books, 1977. ISBN 978-0879491031

- Brian, Denis. Einstein: A Life, New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, 1996. ISBN 0471114596

- Clark, Ronald W. Einstein: The Life and Times, New York, NY: Avon, 1971, ISBN 038001159X

- Corrington, Robert S. Wilhelm Reich: Psychoanalyst and Radical Naturalist, New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003. ISBN 0374250022

- DeMeo, James. The Orgone Accumulator Handbook: Construction Plans, Experimental Use and Protection Against Toxic Energy, Ashland, OR: Natural Energy Works, 1989. ISBN 978-0962185502

- DeMeo, James. Saharasia: The 4000 B.C.E. Origins of Child-Abuse, Sex-Repression, Warfare and Social Violence, In the Deserts of the Old World. Ashland, OR: Natural Energy Works, 2006. ISBN 978-0962185557

- DeMeo, James (ed.). Heretic's Notebook: Emotions, Protocells, Ether-Drift and Cosmic Life Energy, With New Research Supporting Wilhelm Reich, Ashland, OR: Natural Energy Works, 2002. ISBN 978-0962185588

- Herskowitz, Morton. Emotional Armoring: An Introduction to Psychiatric Orgone Therapy, Transactions Press, NY 1998. ISBN 978-3825835552

- Martin, Jim. Wilhelm Reich and the Cold War, Mendocino, CA: Flatland Books, 2000. ISBN 1878124099

- Raknes, Ola. Wilhelm Reich And Orgonomy, American College of Orgonomy Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0967967028

- Reich, Peter. A Book Of Dreams, Dutton Obelisk, 1989. ISBN 978-0525484158

- Sharaf, Myron. Fury on Earth: A Biography of Wilhelm Reich, Da Capo, 1994. ISBN 978-0306805752

External links

All links retrieved November 17, 2023.

- Aetherometry

- Orgone

- Orgone Biophysical Research Lab James DeMeo's Research Website

- orgone energy Skeptic's Dictionary

- Response to Martin Gardner Orgone Biophysical Research Lab

- American College of Orgonomy

- Focal Point: Life Energy Diwan Magazine

- A Skeptical Scrutiny of the Works and Theories of Wilhelm Reich By Roger M. Wilcox

- Marxism and Psychoanalysis: Notes on Wilhelm Reich's life and work

- Wilhelm Reich Akademie

Credits