Slave trade

Slave trade has been and continues to be an economic commodity based on human life. Currently, this practise is called human trafficking and takes place in an underground market that operates outside of a recognized legal system. In other eras, slave trade was conducted openly and legally. Slavery has been a part of human civilization for thousands of years up to the present. It was practised in ancient Egypt, Pre-Greek and Greek society, the Roman Empire, in the Middle East, Europe and the Americas. In the United States, a bitter Civil War was fought over the issue of slavery and slave trade.

The primary reason for the enterprise of slave trade and human trafficking is found in the huge profits that derive from the use of power over vulnerable and/or weaker populatons of people to meet the demand of the international marketplace.

Human Trafficking

Trafficking in human beings is the commercial trade ("smuggling") of human beings, who are subjected to involuntary acts such as begging, sexual exploitation (eg. prostitution and forced marriage), or unfree labour (eg. involuntary servitude or working in sweatshops). Trafficking involves a process of using physical force, fraud, deception, or other forms or coercion or intimidation to obtain, recruit, harbour, and transport people.

Overview

Human trafficking differs from people smuggling. In the latter, people voluntarily request smuggler's service for fees and there is no deception involved in the (illegal) agreement. On arrival at their destination, the smuggled person is either free, or is required to work under a job arranged by the smuggler until the debt is repaid. On the other hand, the trafficking victim is enslaved, or the terms of their debt bondage are fraudulent or highly exploitative. The trafficker takes away the basic human rights of the victim. Victims are sometimes tricked and lured by false promises or physically forced. Some traffickers use coercive and manipulative tactics including deception , intimidation, feigned love, isolation, threat and use of physical force, debt bondage, other abuse, or even force-feeding with drugs to control their victims. [1]

Trafficked persons usually come from the poorer regions of the world, where opportunities are limited and are often from the most vulnerable in society, such as runaways, refugees, or other displaced persons, (especially in post-conflict situations, such as Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina), though they may also come from any social background, class or race. People who are seeking entry to other countries may be picked up by traffickers, and — typically — misled into thinking that they will be free after being smuggled across the border. In some cases, they are captured through slave raiding, although this is increasingly rare. Other cases may involve parents who may sell children to traffickers in order to pay off debts or gain income.

Women, who form the majority of trafficking victims, are particularly at risk from potential kidnappers who exploit lack of opportunities, promise good jobs or opportunities for study, and then force the victims to be prostitutes. Through agents and brokers who arrange the travel and job placements, women are escorted to their destinations and delivered to the employers. Upon reaching their destinations, some women learn that they have been deceived about the nature of the work they will do; most have been lied to about the financial arrangements and conditions of their employment; and all find themselves in coercive and abusive situations from which escape is both difficult and dangerous.

The main motives of a woman (and in some cases an underage girl) to accept an offer from a trafficker is for better financial opportunities for themselves or their family. In many cases traffickers initially offer ‘legitimate’ work. The main types of work offered are in the catering and hotel industry, in bars and clubs, au pair work or to study. Offers of marriage are sometimes used by traffickers as well as threats, intimidation and kidnapping. In the majority of cases, prostitution is where the women end up. Also some (migrating) prostitutes become victims of human trafficking. Some women know they will be working as prostitutes, but they have a too rosy picture of the circumstances and the conditions of the work in the country of destination.[2]

Many women are forced into the sex trade after answering false advertisements and others are simply kidnapped. Thousands of children are sold into the global sex trade every year. Oftentimes they are kidnapped or orphaned, and sometimes they are actually sold by their own families. These children often come from Asia, Africa, and South America.

Traffickers mostly target developing nations where the women are desperate for jobs. The women are often so poor that they can not afford things like food and health care. When the women are offered a position as a nanny or waitress, they often jump to the opportunity.

Men are also at risk of being trafficked for unskilled work predominantly involving hard labour. Other forms of trafficking include bonded and sweatshop labour, forced marriage, and domestic servitude. Children are also trafficked for both labour exploitation and sexual exploitation. On a related issue, children are forced to be child soldiers.

Extent

US State Department data “estimated 600,000 to 800,000 men, women, and children (are) trafficked across international borders each year, approximately 80 percent are women and girls and up to 50 percent are minors. The data also illustrate that the majority of transnational victims are trafficked into commercial sexual exploitation.” [3]. Due to the illegal nature of trafficking and differences in methodology, the exact extent is unknown.

An estimated 14,000 people are trafficked into the United States each year, although again because trafficking is illegal, accurate statistics are difficult. [4] According to the Massachusetts based Trafficking Victims Outreach and Services Networkin Massachusetts alone, there were 55 documented cases of human trafficking in 2005 and the first half of 2006 in Massachusetts. [5] In 2004, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) estimated that 600-800 persons are trafficked into Canada annually and that additional 1,500-2,200 persons are trafficked through Canada into the United States. [6]

In the United Kingdom, 71 women were known to have been trafficked into prostitution in 1998 and the Home Office recognised that the scale is likely greater as the problem is hidden and research estimates that the actual figure could be up to 1,420 women trafficked into the UK during the same peroid. [7] Trafficking in people is increasing in Africa, South Asia and into North America.

Russia is a major source of women trafficked globally for the purpose of sexual exploitation. Russia is also a significant destination and transit country for persons trafficked for sexual and labor exploitation from regional and neighboring countries into Russia, and on to the Gulf states, Europe, Asia, and North America. The ILO estimates that 20 percent of the five million illegal immigrants in Russia are victims of forced labor, which is a form of trafficking. There were reports of trafficking of children and of child sex tourism in Russia. The Government of Russia has made some effort to combat trafficking but has also been criticised for not complying with the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking.[8] [9]

The majority of child trafficking cases are in Asia, although it is a global problem. In Thailand, non-governmental organisations (NGO) have estimated that up to a third of prostitutes are children under 18, many trafficked from outside Thailand. [10] In Ukraine, a survey conducted by the NGO “La Strada-Ukraine” in 2001-2003, based on a sample of 106 women being trafficked out of Ukraine found that 3% were under 18, and the US State Department reported in 2004 that incidents of minors being trafficked was increasing.

Trafficking in people has been facilitated by porous borders and advanced communication technologies, it has become increasingly transnational in scope and highly lucrative. Unlike drugs or arms, people can be "sold" several times. The opening up of Asian markets, porous borders, the end of the Soviet Union and the collapse of the former Yugoslavia have contributed to this globalization.

Some causes of trafficking include:

- Profitability

- Growing deprivation and marginalisation of the poor

- Discrimination in employment against women

- Anti-child labor laws eliminating employment for people under the age of 18

- Anti-marriage laws for people under the age of 18, resulting in single motherhood and a desperate need for income

- Restrictive immigration laws that motivate people to take greater risks

- Insufficient penalties against traffickers

Slave Trade in Antiquity

Historians of ancient civilization rely on evidence found from a variety of sources. Among these are the written information found on inscriptions in rock and the paryri. Research must be conducted in locations where the texts are kept (usually closely monitored) and with the assistance of experts in various ancient languages. It is a daunting task and not one that most governmennts bother to spend money on. A grant from Columbia University in the United States by the Council of Research in the Social Sciences resulted in a published text title, The Slave System of Greek and Roman Antiquity, by William Westermann of the American Philosophical Society in 1955.

From this text come some examples:

The earliest contract for the sale of a slave thus far know to us from Pharaonic Egypt comes from the thirteenth century B.C.E. Despite this, over the course of a thousand years, an exact word that distinguished 'slaves' from 'captives' did not exist.

Artistotle regarded the relationship of master and slave in the same category as husband and wife and father and children. In Politics, he calls these the three fundamental social expressions of relationship between rulers and ruled in any organized society. The Stoics of Greece spoke out against the injustice and cruetly of slavery and Aristotle's vies of what was necessary in a genuinely civilized society.

In the New Testament, Jesus went to see the sick slave of a Roman centurion at Capernaum. The Apostle Paul wrote of slavery in his letter to the Galations.

Historical Development in Europe and the Americas

Mighty black kings in the Bight of Biafra near modern-day Senegal and Benin sold their captives internally and then to European slave traders for such things as metal cookware, rum, livestock, and seed grain. Also during this time, the European powers namely Portugal, Spain, France and England, were vying for majority control of the African slave trade, although having little effect on the continual internal black on black, or Arab trading.

The trade of enslaved Africans in the Atlantic roots in the explorations of Portuguese mariners down the coast of West Africa in 1533. The first Europeans to use African slaves in the New World were the Spaniards who sought auxiliaries for their conquest expeditions and laborers on islands such as Cuba and Hispaniola (mod. Haiti-Dominican Republic) where the alarming decline in the native population had spurred the first royal laws protecting the native population, (Laws of Burgos,1512-1513). After Portugal had succeeded in establishing sugar plantations (enghenos) in northern Brazil ca. 1545, Portuguese merchants on the West African coast began to supply enslaved Africans to the sugar planters there. While at first these planters relied almost exclusively on the native Tupani for slave labor, a titantic shift toward Africans took place after 1570 following a series of epidemics which decimated the already destabilized Tupani communities. By 1630, Africans had replaced the Tupani as the largest contingent of labor on Brazilian sugar plantations, heralding equally the final collapse of the European medieval household tradition of slavery, the rise of Brazil as the largest single destination for enslaved Africans and sugar as the reason that roughly 84% of these Africans were shipped to the New World.

As Britain rose in naval power and controlled more of the Americas, they became the leading slave traders, mostly operating out of Liverpool and Bristol. Other British cities also profited from the slave trade. Birmingham was the largest gun producing city in Britain at the time, and guns were traded for slaves. 75% of all sugar produced in the plantations came to London to supply the highly lucrative coffee houses there.

The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade originated as a shortage of labourin the American colonies and later the USA. The first slaves used by European colonizers were Indigenous peoples of the Americas 'Indian' peoples, but they were not numerous enough and were quickly decimated by European diseases, agricultural breakdown and harsh regime. It was also difficult to get Europeans to emigrate to the colonies, despite incentives such as indentured servitude or even distribution of free land (mainly in the English colonies that became the United States). Massive amounts of labour were needed, initially for mining, and soon even more for the plantations in the labor-intensive growing, harvesting and semi-processing of sugar (also for rum and molasses), cotton and other prized tropical crops which could not be grown profitably — in some cases, could not be grown at all — in the colder climate of Europe. It was also cheaper to import these goods from American colonies than from regions within the Ottoman Empire. To meet this demand for labour European traders thus turned to Western Africa (part of which became known as 'the Slave coast') and later Central Africa into a major source of fresh slaves.

New World destinations

African slaves were brought to Europe and the Americas to supply cheap labor. Central America only imported around 200,000. Europe topped this number at 300,000, North America, however, imported 500,000. The Caribbean was the second largest consumer of slave labor at 4 million. South America, with Brazil taking most of the slaves, imported 4.5 million before the end of the slave trade.

The slave trade was part of the triangular Atlantic trade, then probably the most important and profitable trading route in the world. Ships from Europe would carry a cargo of manufactured trade goods to Africa. They exchanged the trade goods for slaves which they would transport to the Americas, where they sold the slaves and picked up a cargo of agricultural products, often produced with slave labour, for Europe. The value of this trade route was that a ship could make a substantial profit on each leg of the voyage. The route was also designed to take full advantage of prevailing winds and currents: the trip from the West Indies or the southern U.S. to Europe would be assisted by the Gulf Stream; the outward bound trip from Europe to Africa would not be impeded by the same current.

Even though since the Renaissance some ecclesiastics actively pleaded slavery to be against the Christian teachings, as now generally held, others supported the economically opportune slave trade by church teachings and the introduction of the concept of the black man's and white man's separate roles — black men were expected to labour in exchange for the blessings of European civilization, including Christianity.

Economics of slavery

Slavery was involved in some of the most profitable industries of the time: 70% of the slaves brought to the new world were used to produce sugar, the most labour intensive crop. The rest were employed harvesting coffee, cotton, and tobacco, and in some cases in mining. The West Indian colonies of the European powers were some of their most important possessions, so they went to extremes to protect and retain them. For example, at the end of the Seven Years' War in 1763, France agreed to cede the vast territory of New France to the victors in exchange for keeping the minute Antillian island of Guadeloupe (still a French overseas département).

Slave trade profits have been the object of many fantasies. Returns for the investors were not actually absurdly high (around 6% in France in the eighteenth century), but they were higher than domestic alternatives (in the same century, around 5%). Risks — maritime and commercial — were important for individual voyages. Investors mitigated it by buying small shares of many ships at the same time. In that way, they were able to diversify a large part of the risk away. Between voyages, ship shares could be freely sold and bought. All these made slave trade a very interesting investment (Daudin 2004).

End of the Atlantic slave trade

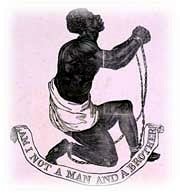

In Britain and in other parts of Europe, opposition developed against the slave trade. Led by the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) and establishment Evangelicals such as William Wilberforce, the movement was joined by many and began to protest against the trade, but they were opposed by the owners of the colonial holdings. Denmark, which had been very active in the slave trade, was the first country to ban the trade through legislation in 1792, which took effect in 1803. Britain banned the slave trade in 1807, imposing stiff fines for any slave found aboard a British ship. That same year the United States banned the importation of slaves. The Royal Navy, which then controlled the world's seas, moved to stop other nations from filling Britain's place in the slave trade and declared that slaving was equal to piracy and was punishable by death.

For the British to end the slave trade, significant obstacles had to be overcome. In the 18th century, the slave trade was an integral part of the Atlantic economy: the economies of the European colonies in the Caribbean, the American colonies, and Brazil required vast amounts of man power to harvest the bountiful agricultural goods. In 1790, the British West Indies islands such as Jamaica and Barbados had a slave population of 524,000 while the French had 643,000 in their West Indian possessions. Other powers such as Spain, the Netherlands, and Denmark had large numbers of slaves in their colonies as well. Despite these high populations more slaves were always required.

Harsh conditions and demographic imbalances left the slave population with well below replacement fertility levels. Between 1600 and 1800, the English imported around 1.7 million slaves to their West Indian possessions. The fact that there were well over a million fewer slaves in the British colonies than had been imported to them illustrates the conditions in which they lived.

British influence

After the British ended their own slave trade, they felt forced by economics to induce other nations to do the same; otherwise, the British colonies would become uncompetitive with those of other nations. The British campaign against the slave trade by other nations was an unprecedented foreign policy effort. Denmark, a small player in the international slave trade, and the United States banned the trade during the same period as Great Britain. Other small trading nations that did not have a great deal to give up, such as Sweden, quickly followed suit, as did the Dutch, who were also by then a minor player.

Four nations objected strongly to surrendering their rights to trade slaves: Spain, Portugal, Brazil (after its independence), and France. Britain used every tool at its disposal to try to induce these nations to follow its lead. Portugal and Spain, which were indebted to Britain after the Napoleonic Wars, slowly agreed to accept large cash payments to first reduce and then eliminate the slave trade. By 1853, the British government had paid Portugal over three million pounds and Spain over one million pounds in order to end the slave trade. Brazil, however, did not agree to stop trading in slaves until Britain took military action against its coastal areas and threatened a permanent blockade of the nation's ports in 1852.

For France, the British first tried to impose a solution during the negotiations at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, but Russia and Austria did not agree. The French people and government had deep misgivings about conceding to Britain's demands. Britain demanded that other nations ban the slave trade and that they had the right to police the ban. The Royal Navy had to be granted permission to search any suspicious ships and seize any found to be carrying slaves, or equipped for doing so. It is especially these conditions that kept France involved in the slave trade for so long. While France formally agreed to ban the trading of slaves in 1815, they did not allow Britain to police the ban, nor did they do much to enforce it themselves. Thus a large black market in slaves continued for many years. While the French people had originally been as opposed to the slave trade as the British, it became a matter of national pride that they not allow their policies to be dictated to them by Britain. Also such a reformist movement was viewed as tainted by the conservative backlash after the French Revolution. The French slave trade thus did not end until 1848.

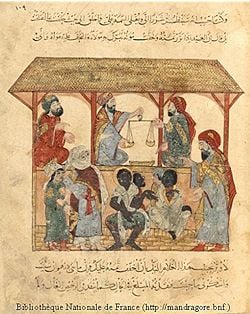

Arab Slave Trade

The Arab slave trade refers to the practice of slavery in the Arab world. The term "Arab" is inclusive, and traders were not exclusively Muslim, nor exclusively Arab: Persians, Berbers, Indians, Chinese and black Africans were involved in this to a greater or lesser degree. From a Western point of view, the subject merges with the Oriental slave trade, which followed two main routes in the Middle Ages:

- Overland routes across the Maghreb and Mashreq deserts (Trans-Saharan route)

- Sea routes to the east of Africa through the Red Sea and Indian Ocean (Oriental route)

The slave trade went to different destinations from the transatlantic slave trade, and supplied African slaves to the Islamic world, which at its peak stretched over three continents from the Atlantic (Morocco, Spain) to India and eastern China.

A recent and controversial topic

The history of the slave trade has given rise to numerous debates amongst historians. Firstly, specialists are undecided on the number of Africans taken from their homes; this is difficult to resolve because of a lack of reliable statistics: there was no census system in medieval Africa. Archival material for the transatlantic trade in the 16th to 18th centuries may seem more useful as a source, yet these record books were often falsified. Historians have to use imprecise narrative documents to make estimates which must be treated with caution: Luiz Felipe de Alencastro[1] states that there were 8 million slaves taken from Africa between the 8th and 19th centuries along the Oriental and the Trans-Saharan routes. Olivier Pétré-Grenouilleau has put forward a figure of 17 million African people enslaved (in the same period and from the same area) on the basis of Ralph Austen's work.[2] Paul Bairoch suggests a figure of 25 million African people subjected to the Arab slave trade, as against 11 million that arrived in the Americas from the transatlantic slave trade.[3]

Another obstacle to a history of the Arab slave trade is the limitations of extant sources. There exist documents from non-African cultures, written by educated men in Arabic, but these only offer an incomplete and often condescending look at the phenomenon. For some years there has been a huge amount of effort going into historical research on Africa. Thanks to new methods and new perspectives, historians can interconnect contributions from archaeology, numismatics, anthropology, linguistics and demography to compensate for the inadequacy of the written record.

In Africa, slaves taken by African owners were often captured, either through raids or as a result of warfare, and frequently employed in manual labor by the captors. Some slaves were traded for goods or services to other African kingdoms.

The Arab slave trade from East Africa is one of the oldest slave trades, predating the European transatlantic slave trade by hundreds of years.[4]Male slaves were employed as servants, soldiers, or laborers by their owners, while female slaves, mostly from Africa, were long traded to the Middle Eastern countries and kingdoms by Arab and Oriental traders, some as female servants, others as sexual slaves. Arab, African, and Oriental traders were involved in the capture and transport of slaves northward across the Sahara desert and the Indian Ocean region into the Middle East, Persia, and the Indian subcontinent. From approximately 650 C.E. until around 1900 C.E., as many African slaves may have crossed the Sahara Desert, the Red Sea, and the Indian Ocean as crossed the Atlantic, and perhaps more. The Arab slave trade continued in one form or another into the early 1900s. Historical accounts and references to slave-owning nobility in Arabia, Yemen and elsewhere are frequent into the early 1920s.[5]

For some people, any mention of the slave-trading past of the Islamic world is rejected as an attempt to minimise the transatlantic trade. Yet a slave trade in the Indian Ocean, Red Sea, and Mediterranean pre-dates the arrival of any significant number of Europeans on the African continent. [6][7]

Historical and geographical context of the Arab slave trade

A brief review of the region and era in which the Oriental and trans-Saharan slave trade took place should be useful here.

The Islamic world

The Muslim religion appeared in the 7th century CE. In the next hundred years it was quickly diffused throughout the Mediterranean area, spread by Arabs who had conquered North Africa after its long occupation by the Berbers; they extended their rule to the Iberian peninsula where they replaced the Visigoth kingdom. Arabs also took control of western Asia from Byzantium and from the Sassanid Persians. These regions therefore had a diverse range of different peoples, and their knowledge of slavery and a trade in African slaves went back to Antiquity. To some extent, these regions were unified by an Islamic culture built on both religious and civic foundations; they used the Arabic language and the dinar (currency) in commercial transactions. Mecca in Arabia, then as now, was the holy city of Islam and pilgrimage centre for all Muslims, whatever their origins. The Qur'ān, the holy book of Islam, seemed to accept slavery, a practice which pre-dated its existence, while setting limits on a master's powers over his slaves. Muslim doctors and sages often encouraged emancipation.

After the fall of the Umayyad dynasty (750), the Muslim world was divided into various political entities (caliphates, emirates, sultanates), often rivals of one another. In the 11th century, the arrival of the Turks from central Asia radically changed the geography of the Near East and of North Africa, with the establishment of the Ottoman Empire (1299-1922).

The framework of Islamic civilisation was a well-developed network of towns and oasis trading centres with the market (souk, bazaar) at its heart. These towns were inter-connected by a system of roads crossing semi-arid regions or deserts. The routes were travelled by convoys, and black slaves formed part of this caravan traffic.

Africa: 8th through 19th centuries

In the 8th century CE, Africa was dominated by Arab-Berbers in the north: Islam moved southwards along the Nile and along the desert trails.

- The Sahara was thinly populated. Nevertheless, since Antiquity there had been cities living on a trade in salt, gold, slaves, cloth, and on agriculture enabled by irrigation: Tahert, Oualata, Sijilmasa, Zaouila, and others. They were ruled by Arab or Berber chiefs (Tuaregs). Their independence was relative and depended on the power of the Maghrebi and Egyptian states.

- In the Middle Ages, sub-Saharan Africa was called Sûdân in Arabic, meaning land of the Blacks. It provided a pool of manual labour for North Africa and Saharan Africa. This region was dominated by certain states: the Ghana Empire, the Empire of Mali, the Kanem-Bornu Empire.

- In eastern Africa, the coasts of the Red Sea and Indian Ocean were controlled by native Muslims, and Arabs were important as traders along the coasts. Nubia had been a "supply zone" for slaves since Antiquity. The Ethiopian coast, particularly the port of Massawa and Dahlak Archipelago, had long been a hub for the exportation of slaves from the interior, even in Aksumite times. The port and most coastal areas were largely Muslim, and the port itself was home to a number of Arab and Indian merchants.[8]

The Solomonic dynasty of Ethiopia often exported Nilotic slaves from their western borderland provinces, or from newly conquered or reconquered Muslim provinces. [9] Native muslim Ethiopian sultanates exported slaves as well, such as the sometimes independent sultanate of Adal.[10] On the coast of the Indian Ocean too, slave-trading posts were set up by Arabs and Persians. The archipelago of Zanzibar, along the coast of present-day Tanzania, is undoubtedly the most notorious example of these trading colonies. East Africa and the Indian Ocean continued as an important region for the Oriental slave trade up until the 19th century. Livingstone and Stanley were then the first Europeans to penetrate to the interior of the Congo basin and to discover the scale of slavery there. The Arab Tippo Tip extended his influence and made many people slaves. After Europeans had settled in the Gulf of Guinea, the trans-Saharan slave trade became less important. In Zanzibar, slavery was abolished late, in 1897, under Sultan Hamoud bin Mohammed.

- The rest of Africa had no direct contact with Muslim slave-traders.

Aims of the slave trade and slavery

Economic motives were the most obvious. The trade resulted in large profits for those who were running it. Several cities became rich and prospered thanks to the traffic in slaves, both in the Sûdân region and in East Africa. In the Sahara desert, chiefs launched expeditions against pillagers looting the convoys. The kings of medieval Morocco had fortresses constructed in the desert regions which they ruled, so they could offer protected stopping places for caravans. The Sultan of Oman transferred his capital to Zanzibar, since he had understood the economic potential of the eastward slave trade.

There were also social and cultural reasons for the trade: in sub-Saharan Africa, possession of slaves was a sign of high social status. In Arab-Muslim areas, harems needed a "supply" of women.

Finally, it is impossible to ignore the religious and racist dimension of this trade. Punishing bad Muslims or pagans was held to be an ideological justification for enslavement: the Muslim rulers of North Africa, the Sahara and the Sahel sent raiding parties to persecute infidels: in the Middle Ages, Islamisation was only superficial in rural parts of Africa.

Racist opinions recurred in the works of Arab historians and geographers: so in the 14th century CE Ibn Khaldun could write "...the Negro nations are, as a rule, submissive to slavery, because (Negroes) have little that is (essentially) human and possess attributes that are quite similar to those of dumb animals... "[11] In the same period, the Egyptian scholar Al-Abshibi wrote, "When he (a black man) is hungry, he steals, and when he is sated, he fornicates".[12]

Geography of the slave trade

"Supply" zones

Merchants of slaves for the Orient stocked up in Europe. Danish merchants had bases in the Volga region and dealt in Slavs with Arab merchants. Circassian slaves were conspicuously present in the harems and there were many odalisques from that region in the paintings of Orientalists. Non-Islamic slaves were valued in the harems, for all roles (gate-keeper, servant, odalisque, houri, musician, dancer, court dwarf). In 9th century Baghdad, the Caliph Al-Amin owned about 7000 black eunuchs (who were completely emasculated) and 4000 white eunuchs (who were castrated).[13] In the Ottoman Empire, the last black eunuch, the slave sold in Ethiopia named Hayrettin Effendi, was freed in 1918. The slaves of Slavic origin in Al-Andalus came from the Varangians who had captured them. They were put in the Caliph's guard and gradually took up important posts in the army (they became saqaliba), and even went to take back taifas after the civil war had led to an implosion of the Western Caliphate. Columns of slaves feeding the great harems of Cordoba, Seville and Grenada were organised by Jewish merchants (mercaderes) from Germanic countries and parts of Northern Europe not controlled by the Carolingian Empire. These columns crossed the Rhône valley to reach the lands to the south of the Pyrenees.

- At sea, Barbary pirates joined in this traffic when they could capture people by boarding ships or by incursions into coastal areas.

- Nubia, Ethiopia and Abyssinia were also "exporting" regions: in the 15th century, there were Abyssinian slaves in India where they worked on ships or as soldiers. They eventually rebelled and took power (dynasty of the Habshi Kings in Bengal 1487-1493).

- The Sûdân region and Saharan Africa formed another "export" area, but it is impossible to estimate the scale, since there is a lack of sources with figures.

- Finally, the slave traffic affected eastern Africa, but the distance and local hostility slowed down this section of the Oriental trade.

Routes

Caravan trails, set up in the 9th century, went past the oases of the Sahara; travel was difficult and uncomfortable for reasons of climate and distance. Since Roman times, long convoys had transported slaves as well as all sorts of products to be used for barter. To protect against attacks from desert nomads, slaves were used as an escort. Any who slowed down the progress of the caravan were killed.

Historians know less about the sea routes. From the evidence of illustrated documents, and travellers' tales, it seems that people travelled on dhows or jalbas, Arab ships which were used as transport in the Red Sea. Crossing the Indian Ocean required better organisation and more resources than overland transport. Ships coming from Zanzibar made stops on Socotra or at Aden before heading to the Persian Gulf or to India. Slaves were sold as far away as India, or even China: there was a colony of Arab merchants in Canton. Chinese slave traders bought black slaves (Hei-hsiao-ssu) from Arab intermediaries or "stocked up" directly in coastal areas of present-day Somalia. Serge Bilé cites a 12th century text which tells us that most well-to-do families in Canton had black slaves whom they regarded as savages and demons because of their physical appearance.[14] The 15th century Chinese emperors sent maritime expeditions, led by Zheng He, to eastern Africa. Their aim was to increase their commercial influence.

Towns and ports implicated in the slave trade

|

|

Current Legal Systems

Today, most people consider slavery to be extinct. Technically legalized slavery no longer exists. "However, slavery still exists in many variant forms in most parts of the world today . . . The new variant forms of slavery - what Bates calls 'new slavery' in his book Disposable People: New Slavery in the Global Economy." [15] Current legal systems are in place throughout the world and serve as a guidepost to combat the new form that slavery has taken.

International law

In 2000 the United Nations adopted the Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, also called the Palermo Convention and two protocols thereto:

- Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children; and

- Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air.

All of these instruments contain elements of the current international law on trafficking in human beings.

Council of Europe

The Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings [11] [12] was adopted by the Council of Europe on 16 May 2005. The aim of the convention is to prevent and combat the trafficking in human beings. Of the 46 members of the Council of Europe, so far 30 have signed the convention and 1 has ratified it. In addition, 1 non-member state has signed the convention (29 June 2006). [13]

United States law

The United States has taken a firm stance against human trafficking both within its borders and beyond. Domestically, human trafficking is prosecuted through the Civil Rights Division, Criminal Section of the United States Department of Justice. Older statutes used to protect 13th Amendment Rights within United States Borders are Title 18 U.S.C., Sections 1581 and 1584. Section 1584 makes it a crime to force a person to work against his will. This compulsion can be effected by use of force, threat of force, threat of legal coercion or by "a climate of fear", that is, an environment wherein individuals believe they may be harmed by leaving or refusing to work. Section 1581 similarly makes it illegal to force a person to work through "debt servitude".

New laws were passed under the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000. The new laws responded to a changing face of trafficking in the United States. It allowed for greater statutory maximum sentences for traffickers, provided resources for protection of and assistance for victims of trafficking and created avenues for interagency cooperation in the field of human trafficking. This law also attempted to encourage efforts to prevent human trafficking internationally, by creating annual country reports on trafficking, as well as by tying financial non-humanitarian assistance to foreign countries to real efforts in addressing human trafficking.

International NPOs, such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, have called on the United States to improve its measures aimed at reducing trafficking. They recommend that the United States more fully implement the "United Nations Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children" and the "United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime" and for immigration officers to improve their awareness of trafficking and support the victims of trafficking. [14][15]

Notes

- ↑ Luiz Felipe de Alencastro, Traite, in Encyclopædia Universalis (2002), corpus 22, page 902.

- ↑ Ralph Austen, African Economic History (1987)

- ↑ Paul Bairoch, Mythes et paradoxes de l'histoire économique, (1994). See also: Economics and World History: Myths and Paradoxes (1993)

- ↑ Mintz, S. Digital History Slavery, Facts & Myths

- ↑ Mintz, S. Digital History Slavery, Facts & Myths

- ↑ Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch, in Les Collections de l'Histoire (April 2001) says:"la traite vers l'Océan indien et la Méditerranée est bien antérieure à l'irruption des Européens sur le continent"

- ↑ Mintz, S. Digital History Slavery, Facts & Myths

- ↑ Pankhurst, Richard. The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century. Asmara, Eritrea: The Red Sea, Inc., 1997, pp.416

- ↑ Pankhurst. Ethiopian Borderlands, pp.432

- ↑ Pankhurst. Ethiopian Borderlands, pp.59

- ↑ Ibn Khaldun The Muqaddimah trans. F.Rosenthal ed. N.J.Dawood (Princeton 1967); see also Jacques Heers, Les négriers en terre d'islam, page 177.

- ↑ François Renault, Serge Daget, Les traites négrières en Afrique, Karthala, p.56

- ↑ Bernard Lewis, Race and Color in Islam (1979)

- ↑ Serge Bilé, La légende du sexe surdimmensionné des Noirs, éditions du Rocher, 2005, p.80: "la plupart des familles aisées de Canton possédaient des esclaves noirs [...] qu'elles tenaient néanmoins pour des sauvages et des démons à cause de leur aspect physique"

- ↑ Patel,A.(2000) Human Rights Quartly Vol 22, No. 3, Johns Hopkins University Press,pp 867-872

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Anstey, Roger: The Atlantic Slave Trade and British abolition, 1760-1810. London: Macmillan, 1975.

- Clarke, Dr. John Henrik: Christopher Columbus and the Afrikan Holocaust. Slavery and the Rise of European Capitalism

- Daudin, Guillaume: "Profitability of slave and long distance trading in context : the case of eightheenth century France", Journal of Economic History, 2004.

- Diop, Er. Cheikh Anta: Precolonial Black Africa: A Comparative Study of the Political and Social Systems of Europe and Black Africa

- Drescher, Seymour: From Slavery to Freedom: Comparative Studies in the Rise and Fall of Atlantic Slavery. London: Macmillan Press, 1999.

- Emmer, P.C.: De Nederlandse slavenhandel 1500-1850 [The Dutch Slave Trade 1500-1850]. Amsterdam and Antwerpen: Uitgeverij De Arbeiderspers, 2000.

- Fage, J.D. A History of Africa (Routledge, 4th edition, 2001 ISBN 0-415-25247-4)

- Lovejoy, Paul E. Transformations in Slavery 1983

- Franklin, John Hope: From Slavery to Freedom

- Rodney, Walter: How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Howard University Press; Revised edition, 1981.

- Thomas, Hugh: The Slave Trade: The History of the Atlantic Slave Trade 1440 - 1870. London:* Picador, 1997.

- Miller, John R: Slave Trade: Combating Human Trafficking. Harvard International Review, 27.4, 2006.

- Westermann, William L.: The Slave Systems of Greek and Roman Antiquity. American Philosophical Society, 1955.

- Williams, Chancellor: Destruction of Black Civilization

- Williams, Eric: Capitalism & Slavery. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994.

- Robert C. Davis, Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast, and Italy, 1500-1800 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2003)

- Allan G. B. Fisher, Slavery and Muslim Society in Africa, ed. C. Hurst (London 1970, 2nd edition 2001)

- Paul E. Lovejoy, Transformations in Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa (Cambridge 2000)

- Ronald Segal, Islam's Black Slaves (Atlantic Books, London 2002)

External links

- Africans in America/Part 1/The Middle Passage

- Breaking the Silence: Learning about the Transatlantic Slave Trade

- The Maafa (African Holocaust)

- A Chronology of Slavery, Abolition, and Emancipation

- Understanding Slavery Initiative; The New Site for Teachers on the British part of the transatlantic slave trade

- African Holocaust African history of legacy of slavery]

- Scale of African slavery revealed Nigeria's 'respectable' slave trade

- Africa's trade in children

Amnesty International

- Amnesty International UK trafficking/forced prostitution

- Amnesty International USA - Human Trafficking

Other organisations and campaigns

- The Anti Trafficking Alliance - Tackling Sexual Trafficking, Supporting its Survivors.

- 'Anti Slavery - Trafficking

- Asia Regional Cooperation to Prevent People Trafficking

- Coalition to Abolish Slavery & Trafficking (CAST)

- The Coalition Against Trafficking in Women

- 'The Emancipation Network: Fighting trafficking with economic empowerment'

- ‘End Child Prostitution, Child Pornography and Trafficking of Children for Sexual Purposes’ international NGO

- World Hope International

Government and international governmental organisations

- Council of Europe - Slaves at the heart of Europe

- European Union: European Commission - Documentation Centre

- U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report, 2005

- US State Department - Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons

- US Department of Justice Human Trafficking Website

- United States Federal Bureau of Investigation

- International Organization for Migration - Counter-Trafficking Programme

- United Nations - Trafficking in Human Beings (This site is an excellent source for international legislation and multi-media video files)

- Trafficking in Minors - United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute

- OSCE Special Representative on Combating Trafficking in Human Beings

- International Labour Organization - Human Trafficking in Asia reports

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- African_slave_trade history

- Atlantic_slave_trade history

- Arab_slave_trade history

- Trafficking_in_human_beings history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.