Difference between revisions of "Santiago Ramón y Cajal" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

However, with the discovery of [[electrical synapse]]s (gap junctions: direct junctions between nerve cells), some have argued that Golgi was at least partially correct. For this work Ramón y Cajal and Golgi shared the [[Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine]] in [[1906 in science|1906]]. | However, with the discovery of [[electrical synapse]]s (gap junctions: direct junctions between nerve cells), some have argued that Golgi was at least partially correct. For this work Ramón y Cajal and Golgi shared the [[Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine]] in [[1906 in science|1906]]. | ||

| − | Ramón y Cajal | + | [[Image:Golgi Hippocampus.jpg|right|thumb|Drawing by Camillo Golgi of a [[hippocampus]] stained with the silver nitrate method]] |

| + | [[Image:Purkinje cell by Cajal.png|thumb|Drawing of a [[Purkinje cell]] in the [[cerebellum]] [[Cerebellar cortex|cortex]] done by Santiago Ramón y Cajal, clearly demonstrating the power of Golgi's staining method to reveal fine detail]] | ||

| + | [[Image:GolgiStainedPyramidalCell.jpg|thumb|A human neocortical [[pyramidal neuron]] stained via [[Golgi's method|Golgi technique]]. Notice the apical dendrite extending vertically above the soma and the numerous basal dendrites radiating laterally from the base of the cell body.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Golgi's method''' is a [[nervous tissue]] [[staining]] technique discovered by [[Italy|Italian]] [[physician]] and [[scientist]] [[Camillo Golgi]] (1843-1926) in [[1873]]. It was initially named the '''black reaction''' (''la reazione nera'') by Golgi, but it became better known as the Golgi stain or method later. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Golgi' staining was famously used by [[Spain|Spanish]] [[neuroanatomist]] [[Santiago Ramón y Cajal]] (1852-1934) to discover a number of novel facts about the organization of the nervous system, inspiring the birth of the [[neuron doctrine]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The cells in nervous tissue are densely packed and little information on their structures and interconnections can be obtained if all the cells are stained. Furthermore, its thin filamentary extensions—the [[axon]] and the [[dendrite]]s—are too slender and transparent to be seen with normal staining techniques. Golgi's method stains a limited number of cells at random in their entirety. The mechanism by which this happens is still largely unknown. Dendrites, as well as the cell soma, are clearly stained in brown and black and can be followed in their entire length, which allowed neuroanatomists to track connections between neurons and to make visible the complex networking structure of many parts of the [[brain]] and [[spinal cord]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Golgi's staining is achieved by impregnating fixed nervous tissue with [[potassium dichromate]] and [[silver nitrate]]. Cells thus stained are filled by [[crystallization|microcrystallization]] of [[silver chromate]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to SynapseWeb [http://synapses.mcg.edu/learn/visualize/visualize.stm], this is the recipe for Golgi's staining technique: | ||

| + | |||

| + | #Immerse a block (approx. 10x5 mm) of [[formaldehyde|formol]]-fixed (or [[paraformaldehyde]]- [[glutaraldehyde]]-perfused) brain tissue into a 2% aqueous solution of [[potassium dichromate]] for 2 days | ||

| + | #Dry the block shortly with [[filter paper]]. | ||

| + | #Immerse the block into a 2% aqueous solution of [[silver nitrate]] for another 2 days. | ||

| + | #Cut sections approx. 20-100 µm thick. | ||

| + | #Dehydrate quickly in [[ethanol]], clear and mount (e.g., into [[Depex]] or [[Enthalan]]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | This technique has since been refined to substitute the silver precipitate with gold by immersing the sample in gold chloride then oxalic acid, followed by removal of the silver by sodium thiosulphate. This preserves a greater degree of fine structure with the ultrastructural details marked by small particles of gold. [http://www.springerlink.com/(f0cb2ybwsglgtnuip5efub55)/app/home/contribution.asp?referrer=parent&backto=issue,5,11;journal,215,243;linkingpublicationresults,1:100182,1] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Cajal said of the Golgi method: | ||

| + | |||

| + | :'' I expressed the surprise which I experienced upon seeing with my own eyes the wonderful revelatory powers of the chrome-silver reaction and the absence of any excitement in the scientific world aroused by its discovery.'' | ||

| + | : ''Recuerdos de mi vida, Vol. 2, Historia de mi labor científica''. Madrid: Moya, 1917, p. 76. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Before the neuron doctrine was accepted, it was widely believed that the nervous system was a reticulum, or a connected meshwork, rather than a system made up of discrete [[cell (biology)|cells]].<ref>[[Eric Richard Kandel|Kandel E.R.]], Schwartz, J.H., Jessell, T.M. 2000. ''[[Principles of Neural Science]]'', 4th ed., Page 23. McGraw-Hill, New York.</ref> This theory, the [[reticular theory]], held that neurons' [[soma (biology)|somata]] mainly provided nourishment for the system.<ref>DeFelipe J. 1998. [http://www.psu.edu/nasa/cajal.htm Cajal]. ''MIT Encyclopedia of the Cognitive Sciences'', MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.</ref> Even after the [[cell theory]] was postulated in the 1830s, most scientists did not believe the theory applied to the brain or nerves. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Cajal Retina.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Drawing by Ramón y Cajal from "Structure of the Mammalian [[Retina]]" Madrid, 1900.]] | ||

| + | The initial failure to accept the doctrine was due in part to inadequate ability to visualize cells using [[microscopes]], which were not developed enough to provide clear pictures of nerves. With the [[staining (microscopy)|cell staining]] techniques of the day, a slice of neural tissue appeared under a microscope as a complex web and individual cells were difficult to make out. Since neurons have a large number of [[neural process]]es an individual cell can be quite long and complex, and it can be difficult to find an individual cell when it is closely associated with many other cells. Thus, a major breakthrough for the neuron doctrine occurred in the late 1800s when Ramón y Cajal used a technique developed by [[Camillo Golgi]] to visualize neurons. The staining technique, which uses a silver solution, only stains one in about a hundred cells, effectively isolating the cell visually and showing that cells are separate and do not form a continuous web. Further, the cells that are stained are not stained partially, but rather all their processes are stained as well. Ramón y Cajal altered the staining technique and used it on samples from younger, less [[myelin]]ated brains, because the technique did not work on myelinated cells.<ref name="sabb"/> He was able to see neurons clearly and produce drawings like the one at right. | ||

| + | |||

| + | For their technique and discovery respectively, Golgi and Ramón y Cajal shared the 1906 [[Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine]]. Golgi could not tell for certain that neurons were not connected, and in his acceptance speech he defended the reticular theory. Ramón y Cajal, in ''his'' speech, contradicted that of Golgi and defended the now accepted neuron doctrine. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A paper written in 1891 by [[Wilhelm von Waldeyer]], a supporter of Ramón y Cajal, debunked the reticular theory and outlined the Neuron Doctrine. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Ramón y Cajal also proposed that the way [[axon]]s grow is via a [[growth cone]] at their ends. He understood that neural cells could sense chemical signals that indicated a direction for growth, a process called [[chemotaxis]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | Ramón y Cajal | + | ==The relation between art and science in Ramón y Cajal's career== |

| + | text | ||

| − | |||

<gallery> | <gallery> | ||

Image:CajalHippocampus.jpeg|Drawing of the neural circuitry of the rodent [[hippocampus]]. {{lang|fr|Histologie du Systeme Nerveux de l'Homme et des Vertebretes}}, Vols. 1 and 2. A. Maloine. Paris. 1911. | Image:CajalHippocampus.jpeg|Drawing of the neural circuitry of the rodent [[hippocampus]]. {{lang|fr|Histologie du Systeme Nerveux de l'Homme et des Vertebretes}}, Vols. 1 and 2. A. Maloine. Paris. 1911. | ||

| Line 34: | Line 65: | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

| − | == | + | ==Ramón y Cajal as writer: ''Vacation Stories''== |

| − | Ramón y Cajal published over 100 scientific works and articles in [[French language|French]], [[Spanish language|Spanish]], and [[German language|German]]. Among his most notable were | + | In 1905, he published five science-fictional "Vacation Stories" under the pen name "Dr. Bacteria." |

| − | + | ||

| − | * | + | The '''Generation of '98''' (also called '''Generation of 1898''' or, in [[Spanish language|Spanish]], ''Generación del 98'' or ''Generación de 1898)'' was a group of [[novel]]ists, [[poet]]s, [[essay]]ists, and [[philosopher]]s active in [[Spain]] at the time of the [[Spanish-American War]] ([[1898]]). |

| + | |||

| + | The group reinvigorated Spanish letters and restored Spain to a position of intellectual and literary [[prominence]] that it had not held for centuries. It was important to the group to define Spain, as a cultural and historical entity. The name ''Generación del 98'' was coined by Jose Martínez Ruiz, commonly known as [[Azorín]], in [[1913]], alluding to the moral, political, and social crisis in Spain produced by the disaster and the loss of the colonies of Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines after defeat in the [[Spanish-American War]] that same year. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The writers, poets and playwrights of this generation maintained a strong intellectual unity, opposed the [[Spain under the Restoration|Restoration]] of the monarchy in Spain, revived Spanish literary myths, and broke with classical schemes of [[literary genre]]s. They brought back traditional and lost words and always alluded to the old kingdom of [[Castilla]], with many supporting the idea of [[Autonomous Communities of Spain|Spanish Regionalism]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The majority of these texts that were written in this literary era were produced in the years immediately after 1910 and are generally marked by the justification of [[Extremism|radicalism]] and [[rebellion]]. Examples of this are the last poems incorporated to "Campos de Castilla", of [[Antonio Machado]]; [[Miguel de Unamuno]]'s articles written during the [[First World War]]; or in the essayistic texts of [[Pío Baroja]].) | ||

| + | |||

| + | The criticism of the "Generation of '98" today from modern intellectuals is that the group was characterized by an increase of egoism, by a great feeling of frustration, especially about the Spain of those days, by the neo-romantic exaggeration of the individual and by the imitation of contemporary European artistic movements. | ||

| + | |||

| + | On the other hand, left-wing revolutionary writers of the [[1930s]] claim that the negative interpretation of the intellectual rebellion of the "Generation of '98" is because of the [[ideology|ideological]] detachment of the critics from the revolutionaries. Supporters of the revolutionaries identified themselves with the intellectual faction of the [[petite bourgeoisie]], who felt empowered to combat a [[spirituality|spiritual]]ist, [[nationalist]] and [[counterrevolutionary]] attitude. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Biography == | ||

| + | The son of Justo Ramón and Antonia Cajal, Ramón y Cajal was born of Aragonese parents in [[Petilla de Aragón]], an enclave in [[Aragon]], [[Spain]]. As a child he was transferred between many different schools because of his poor behaviour and [[Authoritarianism|anti-authoritarian]] attitude. An extreme example of his precociousness and rebelliousness is his imprisonment at the age of eleven for destroying the town gate with a homemade [[cannon]]. He was an avid painter, artist, and [[gymnast]]. He worked for a time as a shoemaker and barber, and was well known for his pugnacious attitude. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Ramón y Cajal attended the medical school of [[Zaragoza]], from which he graduated in 1873. After a competitive examination, he served as a medical [[officer (armed forces)|officer]] in the [[Spanish Army]]. He took part in an expedition to Cuba in 1874-75, where he contracted [[malaria]] and [[tuberculosis]]. After returning to Spain he married Silveria Fañanás García in 1879, with whom he had four daughters and three sons. He was appointed as a [[university]] [[professor]] at [[Universitat de València|Valencia]] in 1881, and in 1883 he received his [[Doctor of Medicine|medical degree]] in [[Madrid]]. He later held professorships in both [[Barcelona]] and Madrid. He was Director of the Zaragoza Museum (1879), Director of the National Institute of Hygiene (1899), and founder of the {{lang|es|''Laboratorio de Investigaciones Biológicas''}} (1922) (later renamed to the {{lang|es|''Instituto Cajal''}}, or [[Cajal Institute]]). He died in Madrid in 1934. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Selected works == | ||

| + | Ramón y Cajal published over 100 scientific works and articles in [[French language|French]], [[Spanish language|Spanish]], and [[German language|German]]. Among his most notable were the following: | ||

| + | |||

| + | (fix accent marks) | ||

| + | |||

| + | *date: ''Degeneration and regeneration of the nervous system'' 2 vols. | ||

| + | *''Manual of normal histology and micrographic technique'' | ||

| + | *''Elements of histology'' | ||

| + | *''Manual of general [[pathology|pathological]] [[anatomy]]'' | ||

| + | *''New ideas on the fine anatomy of the nerve centres'' | ||

| + | *''Histology of the Nervous System of Man and Vertebrates'' 2 vols. | ||

| + | *''The [[retina]] of vertebrates'' | ||

| + | *1905: ''Vacation Stories'' (''Cuentos de vacaciones'') | ||

| + | *Recollections of My Life (''Recuerdos de mi vida'') | ||

| + | *1897: Advice for a Young Investigator (''Reglas y consejos sobre le investigación cientifica'') | ||

| + | *1921: ''Cafe Conversations'' (''Charlas de Café'') | ||

| + | *1934: ''The World From an Eighty-Year-Old's Point of View'' ("El mundo visto a los ochenta años") | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * | + | *Everdell, W.R. 1998. ''The First Moderns''. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226224805 |

| − | + | *Ramón y Cajal, S. 1937. ''Recuerdos de mi Vida''. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 8420622907 | |

| − | + | *Ramón y Cajal, S. 1999 (1897). ''Advice for a Young Investigator''. Trans. N. Swanson and L.W. Swanson. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 0262681501 | |

| − | + | *Ramón y Cajal, S. 2001 (1905). ''Vacation Stories: Five Science Fiction Tales''. Trans. L. Otis. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

Revision as of 16:50, 19 June 2007

Santiago Ramón y Cajal (May 1 1852 – October 17 1934) was a Spanish histologist, physician, and Nobel laureate. He is considered to be one of the founders of modern neuroscience.

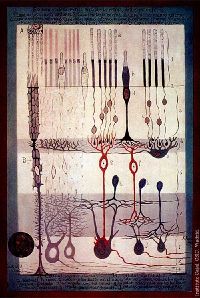

Contributions to neuroscience

Ramón y Cajal's most famous studies were on the fine structure of the central nervous system. Cajal used a histological staining technique developed by his contemporary Camillo Golgi. Golgi found that by treating brain tissue with a silver chromate solution, a relatively small number of neurons in the brain were darkly stained. This allowed Golgi to resolve in detail the structure of individual neurons and led him to conclude that nervous tissue was a continuous reticulum (or web) of interconnected cells much like those in the circulatory system.

Using Golgi's method, Ramón y Cajal reached a very different conclusion. He postulated that the nervous system is made up of billions of separate neurons and that these cells are polarized. Rather than forming a continuous web, Cajal suggested that neurons communicate with each other via specialized junctions called "synapses", a term that was coined by Sherrington in 1897. This hypothesis became the basis of the neuron doctrine, which states that the individual unit of the nervous system is a single neuron. Electron microscopy later showed that a plasma membrane completely enclosed each neuron, supporting Cajal's theory, and weakening Golgi's reticular theory.

However, with the discovery of electrical synapses (gap junctions: direct junctions between nerve cells), some have argued that Golgi was at least partially correct. For this work Ramón y Cajal and Golgi shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1906.

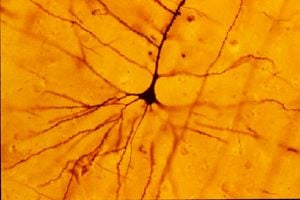

Golgi's method is a nervous tissue staining technique discovered by Italian physician and scientist Camillo Golgi (1843-1926) in 1873. It was initially named the black reaction (la reazione nera) by Golgi, but it became better known as the Golgi stain or method later.

Golgi' staining was famously used by Spanish neuroanatomist Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1852-1934) to discover a number of novel facts about the organization of the nervous system, inspiring the birth of the neuron doctrine.

The cells in nervous tissue are densely packed and little information on their structures and interconnections can be obtained if all the cells are stained. Furthermore, its thin filamentary extensions—the axon and the dendrites—are too slender and transparent to be seen with normal staining techniques. Golgi's method stains a limited number of cells at random in their entirety. The mechanism by which this happens is still largely unknown. Dendrites, as well as the cell soma, are clearly stained in brown and black and can be followed in their entire length, which allowed neuroanatomists to track connections between neurons and to make visible the complex networking structure of many parts of the brain and spinal cord.

Golgi's staining is achieved by impregnating fixed nervous tissue with potassium dichromate and silver nitrate. Cells thus stained are filled by microcrystallization of silver chromate.

According to SynapseWeb [1], this is the recipe for Golgi's staining technique:

- Immerse a block (approx. 10x5 mm) of formol-fixed (or paraformaldehyde- glutaraldehyde-perfused) brain tissue into a 2% aqueous solution of potassium dichromate for 2 days

- Dry the block shortly with filter paper.

- Immerse the block into a 2% aqueous solution of silver nitrate for another 2 days.

- Cut sections approx. 20-100 µm thick.

- Dehydrate quickly in ethanol, clear and mount (e.g., into Depex or Enthalan).

This technique has since been refined to substitute the silver precipitate with gold by immersing the sample in gold chloride then oxalic acid, followed by removal of the silver by sodium thiosulphate. This preserves a greater degree of fine structure with the ultrastructural details marked by small particles of gold. [2]

Cajal said of the Golgi method:

- I expressed the surprise which I experienced upon seeing with my own eyes the wonderful revelatory powers of the chrome-silver reaction and the absence of any excitement in the scientific world aroused by its discovery.

- Recuerdos de mi vida, Vol. 2, Historia de mi labor científica. Madrid: Moya, 1917, p. 76.

Before the neuron doctrine was accepted, it was widely believed that the nervous system was a reticulum, or a connected meshwork, rather than a system made up of discrete cells.[1] This theory, the reticular theory, held that neurons' somata mainly provided nourishment for the system.[2] Even after the cell theory was postulated in the 1830s, most scientists did not believe the theory applied to the brain or nerves.

The initial failure to accept the doctrine was due in part to inadequate ability to visualize cells using microscopes, which were not developed enough to provide clear pictures of nerves. With the cell staining techniques of the day, a slice of neural tissue appeared under a microscope as a complex web and individual cells were difficult to make out. Since neurons have a large number of neural processes an individual cell can be quite long and complex, and it can be difficult to find an individual cell when it is closely associated with many other cells. Thus, a major breakthrough for the neuron doctrine occurred in the late 1800s when Ramón y Cajal used a technique developed by Camillo Golgi to visualize neurons. The staining technique, which uses a silver solution, only stains one in about a hundred cells, effectively isolating the cell visually and showing that cells are separate and do not form a continuous web. Further, the cells that are stained are not stained partially, but rather all their processes are stained as well. Ramón y Cajal altered the staining technique and used it on samples from younger, less myelinated brains, because the technique did not work on myelinated cells.[3] He was able to see neurons clearly and produce drawings like the one at right.

For their technique and discovery respectively, Golgi and Ramón y Cajal shared the 1906 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Golgi could not tell for certain that neurons were not connected, and in his acceptance speech he defended the reticular theory. Ramón y Cajal, in his speech, contradicted that of Golgi and defended the now accepted neuron doctrine.

A paper written in 1891 by Wilhelm von Waldeyer, a supporter of Ramón y Cajal, debunked the reticular theory and outlined the Neuron Doctrine.

Ramón y Cajal also proposed that the way axons grow is via a growth cone at their ends. He understood that neural cells could sense chemical signals that indicated a direction for growth, a process called chemotaxis.

The relation between art and science in Ramón y Cajal's career

text

Ramón y Cajal as writer: Vacation Stories

In 1905, he published five science-fictional "Vacation Stories" under the pen name "Dr. Bacteria."

The Generation of '98 (also called Generation of 1898 or, in Spanish, Generación del 98 or Generación de 1898) was a group of novelists, poets, essayists, and philosophers active in Spain at the time of the Spanish-American War (1898).

The group reinvigorated Spanish letters and restored Spain to a position of intellectual and literary prominence that it had not held for centuries. It was important to the group to define Spain, as a cultural and historical entity. The name Generación del 98 was coined by Jose Martínez Ruiz, commonly known as Azorín, in 1913, alluding to the moral, political, and social crisis in Spain produced by the disaster and the loss of the colonies of Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines after defeat in the Spanish-American War that same year.

The writers, poets and playwrights of this generation maintained a strong intellectual unity, opposed the Restoration of the monarchy in Spain, revived Spanish literary myths, and broke with classical schemes of literary genres. They brought back traditional and lost words and always alluded to the old kingdom of Castilla, with many supporting the idea of Spanish Regionalism.

The majority of these texts that were written in this literary era were produced in the years immediately after 1910 and are generally marked by the justification of radicalism and rebellion. Examples of this are the last poems incorporated to "Campos de Castilla", of Antonio Machado; Miguel de Unamuno's articles written during the First World War; or in the essayistic texts of Pío Baroja.)

The criticism of the "Generation of '98" today from modern intellectuals is that the group was characterized by an increase of egoism, by a great feeling of frustration, especially about the Spain of those days, by the neo-romantic exaggeration of the individual and by the imitation of contemporary European artistic movements.

On the other hand, left-wing revolutionary writers of the 1930s claim that the negative interpretation of the intellectual rebellion of the "Generation of '98" is because of the ideological detachment of the critics from the revolutionaries. Supporters of the revolutionaries identified themselves with the intellectual faction of the petite bourgeoisie, who felt empowered to combat a spiritualist, nationalist and counterrevolutionary attitude.

Biography

The son of Justo Ramón and Antonia Cajal, Ramón y Cajal was born of Aragonese parents in Petilla de Aragón, an enclave in Aragon, Spain. As a child he was transferred between many different schools because of his poor behaviour and anti-authoritarian attitude. An extreme example of his precociousness and rebelliousness is his imprisonment at the age of eleven for destroying the town gate with a homemade cannon. He was an avid painter, artist, and gymnast. He worked for a time as a shoemaker and barber, and was well known for his pugnacious attitude.

Ramón y Cajal attended the medical school of Zaragoza, from which he graduated in 1873. After a competitive examination, he served as a medical officer in the Spanish Army. He took part in an expedition to Cuba in 1874-75, where he contracted malaria and tuberculosis. After returning to Spain he married Silveria Fañanás García in 1879, with whom he had four daughters and three sons. He was appointed as a university professor at Valencia in 1881, and in 1883 he received his medical degree in Madrid. He later held professorships in both Barcelona and Madrid. He was Director of the Zaragoza Museum (1879), Director of the National Institute of Hygiene (1899), and founder of the Laboratorio de Investigaciones Biológicas (1922) (later renamed to the Instituto Cajal, or Cajal Institute). He died in Madrid in 1934.

Selected works

Ramón y Cajal published over 100 scientific works and articles in French, Spanish, and German. Among his most notable were the following:

(fix accent marks)

- date: Degeneration and regeneration of the nervous system 2 vols.

- Manual of normal histology and micrographic technique

- Elements of histology

- Manual of general pathological anatomy

- New ideas on the fine anatomy of the nerve centres

- Histology of the Nervous System of Man and Vertebrates 2 vols.

- The retina of vertebrates

- 1905: Vacation Stories (Cuentos de vacaciones)

- Recollections of My Life (Recuerdos de mi vida)

- 1897: Advice for a Young Investigator (Reglas y consejos sobre le investigación cientifica)

- 1921: Cafe Conversations (Charlas de Café)

- 1934: The World From an Eighty-Year-Old's Point of View ("El mundo visto a los ochenta años")

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Everdell, W.R. 1998. The First Moderns. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226224805

- Ramón y Cajal, S. 1937. Recuerdos de mi Vida. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 8420622907

- Ramón y Cajal, S. 1999 (1897). Advice for a Young Investigator. Trans. N. Swanson and L.W. Swanson. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 0262681501

- Ramón y Cajal, S. 2001 (1905). Vacation Stories: Five Science Fiction Tales. Trans. L. Otis. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

External links

- The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1906

- Life and discoveries of Cajal

- Ramon y Cajal, an Aragonese Nobel Prize

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.