Encyclopedia, Difference between revisions of "Søren Kierkegaard" - New World

Keisuke Noda (talk | contribs) m |

Keisuke Noda (talk | contribs) m (Soren Kierkegaard moved to Søren Kierkegaard) |

||

| Line 265: | Line 265: | ||

[[Category:Philosophers|Kierkegaard, Søren]] | [[Category:Philosophers|Kierkegaard, Søren]] | ||

[[Category:Søren Kierkegaard]] | [[Category:Søren Kierkegaard]] | ||

| + | [[category:philosophy and religion]] | ||

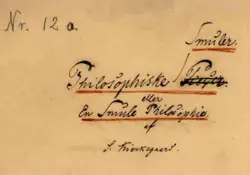

| + | [[Image:Kierkegaard.jpg|200px|thumb|right|Søren Kierkegaard]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Søren Kierkegaard's philosophy''' has been a major influence in the development of [[20th century]] philosophy, especially in the movements of [[Existentialism]] and [[Postmodernism]]. [[Søren Kierkegaard]] was a [[19th century]] Danish philosopher who has been generally considered the "Father of Existentialism". His philosophy also influenced the development of [[existential psychology]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | His writings, many of which were written pseudonymously, reflected not only the trend at the time to write pseudonymously but also his idea that a person or a self is made up of many faces and facets, as his book titled ''[[Philosophical Fragments]]'' would indicate. Kierkegaard did not like the systems that were brought on by philosophers such as [[Immanuel Kant]] and [[Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel]] before him. He measured himself against the backdrop of philosophy which was introduced by [[Socrates]] and preferred a philosophy that was fragmented and made deep insights, without committing to an encompassing all-explaining system. | ||

| + | |||

| + | One of Kierkegaard's recurrent themes is the importance of the self, and the self's relation to the world as being grounded in self-reflection and introspection. In ''[[Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments]]'', he argues that "subjectivity is truth" and "truth is subjectivity"; that is, that the self is the ultimate governor of what life is and what life means. He also believed in the infinity of the self, explaining that the self could not be fully known or understood, because it is infinite. In this way his thought reflects the Christian idea of the soul, which is immortal; but Kierkegaard was not speaking about the immortality of the self as much as the depth of the soul, of a person's being. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Themes in his philosophy== | ||

| + | ===Alienation=== | ||

| + | [[Alienation]] is a term applied to a wide variety of phenomena including: any feeling of separation from, and discontent with, society; feeling that there is a moral breakdown in society; feelings of powerlessness in the face of the solidity of social institutions; the impersonal, dehumanised nature of large-scale and bureaucratic social organisations. [http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/cgi-local/DHI/dhi.cgi?id=dv1-06] Kierkegaard recognizes and accepts the notion of alienation, although he phrases it and understands it in his own distinctly original terms. For Kierkegaard, the present age is a reflective age—one that values objectivity and thought over action, lip-service to ideals rather than action, discussion over action, publicity and advertising to reality, and fantasy to the real world. For Kierkegaard, the meaning of values has been sucked out of them by a lack of authority. Instead of the authority of the past or the [[Bible]] or any other great and lasting voice, we have emptiness and uncertainty. | ||

| + | |||

| + | We have lost meaning because the accepted criterion of reality and truth is objective thought—that which can be proved with [[logic]], historical research, or [[scientific analysis]]. But humans are not [[robot]]s or computer programs or [[amoeba]]— humans need reasons to live and die, and what truly gives meaning to human life is something that cannot be formulated into mathematical, historical or logical terms. We cannot think our choices in life, we must live them; and even those choices that we often think about become different once life itself enters into the picture. For Kierkegaard, the type of objectivity that a scientist or historian might use misses the point—humans are not motivated and do not find meaning in life through pure objectivity. Instead, they find it through [[passion]], desire, and moral and religious commitment. These phenomena are not objectively provable—nor do they come about through any form of analysis of the external world; they come about through inward reflection, a way of looking at one’s life that evades objective scrutiny. Instead, true self-worth originates in a relation to something that transcends human powers, something that provides a meaning because it inspires awe and wonder and demands total and absolute commitment in achieving it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Kierkegaard’s analysis of the present age uses terms that resemble but are not exactly coincident with Hegel and [[Marx's theory of alienation]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Abstraction=== | ||

| + | A key element of Kierkegaard’s critique of modernity is the mention of [[money]] —which he calls an [[abstraction]]. An abstraction is something that only has a reality in an [[ersatz]] reality. It is not tangible, and only has meaning within an artificial context, which ultimately serves devious and deceptive purposes. It is a figment of thought that has no concrete reality, either now or in the future. | ||

| + | |||

| + | How is money an abstraction? Money gives the illusion that it has a direct relationship to the work that is done. That is, the work one does is worth so much, equals so much money. In reality, however, the work one does is an expression of who one is as a person; it expresses one's goals in life and its ultimate meaning. As a person, the work one performs is supposed to be an external realization of one's relationship to others and to the world. It is one's way of making the world a better place for oneself and for others. What reducing work to a monetary value does is to replace the concrete reality of one's everyday struggles with the world—to give it shape, form and meaning—with an abstraction. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Death=== | ||

| + | [[Death]] is inevitable and temporally unpredictable. Kierkegaard believed that individuals needed to sincerely and intensely come to realize the truth of that fact in order to realize their passion for the task of obtaining true selfhood. Kierkegaard accuses society of being in death-denial and believes that even though people see death all around them and objectively grasp death, most people have not understood death subjectively. Instead of viewing death in a detached manner, as in "Death'll happen someday", it is important to look at death as part of a person's life. For example, in ''Concluding Unscientific Postscript'', Kierkegaard notes that people never think to say, "I shall certainly attend your party, but I must make an exception for the contingency that a roof tile happens to blow down and kill me; for in that case, I cannot attend." | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Dread or anxiety=== | ||

| + | [[Image:The leap.png|250px|thumb|In [[Groundhog Day (film)|Groundhog Day]], Phil Connors makes a leap from a building. Kierkegaard would say Phil had gone through anxiety/dread about jumping, but came to embrace Death and his freedom to jump.]] | ||

| + | For Kierkegaard, [[Existential dread|dread]] or anxiety/[[angst]] (depending on the translation and context) is unfocused fear. Kierkegaard uses the example of a man standing on the edge of a tall building or cliff. When the man looks over the edge, he experiences a focused fear of falling, but at the same time, the man feels a terrifying impulse to throw himself intentionally off the edge. That experience is dread or anxiety because of our complete freedom to choose to either throw oneself off or to stay put. The mere fact that one has the possibility and freedom to do something, even the most terrifying of possibilities, triggers immense feelings of dread. Kierkegaard called this our "dizziness of freedom". | ||

| + | |||

| + | In ''[[The Concept of Dread]]'', Kierkegaard focuses on the first dread experienced by man: [[Adam and Eve|Adam]]'s choice to eat from God's forbidden tree of knowledge or not. Since the concepts of good and evil did not come into existence before Adam ate the fruit, which is now dubbed [[original sin]], Adam had no concept of good and evil, and did not know that eating from the tree was "evil". What he did know was that God told him not to eat from the tree. The dread comes from the fact that God's prohibition itself implies that Adam is free and that he could choose to obey God or not. After Adam ate from the tree, sin was born. So, according to Kierkegaard, dread precedes sin, and it is dread that leads Adam to sin. Kierkegaard mentions that ''dread is the presupposition for hereditary sin''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | However, Kierkegaard also mentions that dread is a way for humanity to be saved as well. Anxiety informs us of our choices, our self-awareness and personal responsibility, and brings us from a state of un-self-conscious immediacy to self-conscious reflection. (Jean-Paul Sartre calls these terms pre-reflexive consciousness and reflexive consciousness.) An individual becomes truly aware of their potential through the experience of dread. So, dread may be a possibility for sin, but dread can also be a recognition or realization of one's true identity and freedoms. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Quotation|Whoever has learned to be anxious in the right way has learned the ultimate.|Søren Kierkegaard|The Concept of Dread}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Despair=== | ||

| + | {{Quotation|Is despair an excellence or a defect? Purely dialectically, it is both. The possibility of this sickness is man's superiority over the animal, for it indicates infinite sublimity that he is spirit. Consequently, to be able to despair is an infinite advantage, and yet to be in despair is not only the worst misfortune and misery—no, it is ruination.|Søren Kierkegaard|The Sickness Unto Death}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Most emphatically in ''[[The Sickness Unto Death]]'' but also in ''[[Fear and Trembling]]'' Kierkegaard argues that humans are made up of three parts: the finite, the infinite, and the "relationship of the two to itself." The finite (sense, body, knowledge) and the infinite (paradox and the capacity to have faith) always exist in a state of tension. That tension, as it is aware of itself, is the "self." When the self is lost, either to [[insensibility]] or [[exuberance]], the person is in a state of [[Existential despair|despair]]. Notably, one does not have to be conscious of one's despair, or to feel oneself to be anything but happy. Despair is, instead, the loss of self. In ''[[Either/Or]]'', Kierkegaard has two [[epistolary novel]]s in two volumes. The first letter-writer is an aesthete whose wildness of belief and imagination lead him to a meaningless life of egoistic despair. The second volume's author is a judge who lives his life by strict Christian laws. Because he works entirely upon received law and never uses belief or soulfulness, he lives a life of ethical despair. The third sphere of life, the only one in which an individual can find some measure of freedom from despair, is the religious sphere. This consists in a sort of synthesis between the first two. In ''[[Fear and Trembling]]'', Kierkegaard argues that the choice of [[Abraham]] to obey the private, anti-ethical, religious commandment of God to sacrifice his son is the perfect act of self. If Abraham were to blithely obey, his actions would have no meaning. It is only when he acts ''with fear and trembling'' that he demonstrates a full awareness and the actions of the self, as opposed to the actions of either the finite or infinite portions of humanity. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Ethics=== | ||

| + | [[Image:Abraham.jpg|250px|right|thumb|In [[Fear and Trembling]], Johannes de Silentio analyzes [[Abraham]]'s action to sacrifice [[Isaac]]. Silentio argues that Abraham is a knight of faith.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Many philosophers who initially read Kierkegaard, especially ''[[Fear and Trembling]]'', often come to the conclusion that he supports a [[divine command theory|divine command]] law of ethics. The divine command theory is a [[Meta-ethics|metaethical]] theory which claims moral values are whatever is commanded by a god or gods. However, Kierkegaard (through his pseudonym Johannes de Silentio) is not arguing that morality is created by [[God]]; instead, he would argue that a divine command from God ''transcends'' ethics. This distinction means that God does not necessarily create human morality: it is up to us as individuals to create our own morals and values. But any religious person must be prepared for the event of a divine command from God that would take precedence over all moral and rational obligations. Kierkegaard called this event the ''teleological suspension of the ethical''. Abraham, the [[knight of faith]], chose to obey God unconditionally, and was rewarded with his son, his faith, and the title of ''Father of Faith''. Abraham transcended ethics and leapt into faith. | ||

| + | |||

| + | But there is no valid logical argument one can make to claim that morality ought to be or can be suspended in any given circumstance, or ever. Thus, Kierkegaard believes ethics and faith are separate stages of consciousness. The choice to obey God unconditionally is a true existential 'either/or' decision faced by the individual. Either one chooses to live in faith (the religious stage) or to live ethically (the ethical stage). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Individuality=== | ||

| + | [[Image:Solar eclipse 2005-crowds Madrid.jpg|200px|thumb|Try not to get lost in the crowd. Assert your individuality.]] | ||

| + | For Kierkegaard, true [[Individual|individuality]] is called selfhood. Becoming aware of our true self is our true task and endeavor in life—it is an ethical imperative, as well as preparatory to a true religious understanding. Individuals can exist at a level that is less than true selfhood. We can live, for example, simply in terms of our [[pleasure]]s—our immediate satisfaction of desires, propensities, or distractions. In this way, we glide through life without direction or purpose. To have a direction, we must have a purpose that defines for us the meaning of our lives. | ||

| + | |||

| + | An individual person, for Kierkegaard, is a particular that no abstract formula or definition can ever capture. Including the individual in a group or subsuming a human being as simply a member of a species is a reduction of the true meaning of life for individuals. What philosophy or politics try to do is to categorize and pigeonhole individuals by group characteristics instead of individual differences. For Kierkegaard, those differences are what make us who we are. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Kierkegaard’s critique of the modern age, therefore, is about the loss of what it means to be an individual. Modern society contributes to this dissolution of what it means to be an individual. Through its production of the false idol of the Public, it diverts attention away from individuals to a mass public that loses itself in abstractions, communal dreams, and fantasies. It is helped in this task by the media and the mass production of products to keep it distracted. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Pathos (Passion)=== | ||

| + | For Kierkegaard, in order to apprehend the absolute, the mind must radically empty itself of objective content. What supports this radical emptying, however, is the desire for the absolute. Kierkegaard names this desire ''[[Passion]]''. ([http://www.bib.uab.es/pub/enrahonar/0211402Xn29p119.pdf Kangas]) | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to Kierkegaard, the human self desires that which is beyond [[reason]]. Desire itself appears to be a desire for the infinite, as Plato once wrote. Even the desire to propagate, according to [[Plato]], is a kind of desire for [[immortality]]—that is, we wish to live on in time through our children and their children. [[Erotic love]] itself appears as an example of this desire for something beyond the purely finite. It is a taste of what could be, if only it could continue beyond the boundaries of [[time]] and [[space]]. As the analogy implies, humans seek something beyond the here and now. The question remains, however, why is it that human pathos or passion is the most precious thing? In some ways, it might have to do with our status as existential beings. It is not thought that gets us through life—it is action; and what motivates and sustains action is passion, the desire to overcome hardships, pain, and suffering. It is also passion that enables us to die for ideals in the name of a higher reality. While a scientist might see this as plain emotion or simple animal desire, Kierkegaard sees it as that which binds to the source of life itself. The desire to live, and to live in the right way, for the right reasons, and with the right desires, is a holy and sacred force. | ||

| + | |||

| + | One can also look at this from the perspective of what the meaning of our existence is. Why suffer what humans have suffered, the pain and despair—what meaning can all of this have? For Kierkegaard, there is no meaning unless passion, the emotions and will of humans, has a divine source. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Passion is closely aligned with faith in Kierkegaard's thought. [[Faith]] as a passion is what drives humans to seek reality and truth in a transcendent world, even though everything we can know intellectually speaks against it. To live and die for a belief, to stake everything one has and is in the belief in something that has a higher meaning than anything in the world—this is belief and passion at their highest. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Subjectivity=== | ||

| + | [[Image:Textbooks.JPG|250px|thumb|Scientific and historical textbooks are a source of objective knowledge and are existentially indifferent. Nothing subjective can be obtained from them (Subjectivity in this context does not mean bias or opinion, but the relationship between the individual and the objective).]] | ||

| + | Kierkegaard writes in ''Concluding Unscientific Postcript to the Philosophical Fragments'' the following cryptic line: "[[Subjectivity]] is Truth". To understand Kierkegaard’s concept of the individual, it is important to look at what he says regarding subjectivity. What is subjectivity? In very rough terms, subjectivity refers to what is personal to the individual—what makes the individual ''who he is in distinction from others''. It is what is inside—what the individual can see, feel, think, imagine, dream, etc. It is often opposed to objectivity—that which is outside the individual, which the indvidual and others around can feel, see, measure, and think about. Another way to interpret subjectivity is the ''unique'' relationship between the subject and object. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Scientists and historians, for example, study the objective world, hoping to elicit the truth of nature—or perhaps the truth of [[history]]. In this way, they hope to predict how the future will unfold in accordance with these laws. In terms of history, by studying the past, the individual can perhaps elicit the laws that determine how events will unfold—in this way the individual can predict the future with more exactness and perhaps take control of events that in the past appeared to fall outside the control of humans. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In most respects, Kierkegaard did not have problems with [[science]] or the scientific endeavor. He would not disregard the importance of objective knowledge. Where the scientist or historian finds certainty, however, Kierkegaard noted very accurately that results in science change as the tools of observation change. But Kierkegaard's special interest was in history. His most vehement attacks came against those who believed that they had understood history and its laws—and by doing so could ascertain what a human’s true self is. That is, the assumption is that by studying history I can come to know who I really am as a person. Kierkegaard especially accused Hegel's philosophy of falling prey to this assumption. | ||

| + | |||

| + | For Kierkegaard, this is a ridiculous argument at best, and a harmful notion at worst. It undermines the meaning of what a self is. For Kierkegaard, the individual comes to know who he is by an intensely personal and passionate pursuit of what will give meaning to my life. As an existing individual, who must come to terms with everyday life, overcome its obstacles and setbacks, who must live and die, the single individual has a life that no one else will ever live. In dealing with what life brings my way, the individual must encounter them with all his psycho-physical resources. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Subjectivity is that which the individual has and no one else does. But what does it mean to have something like this? It cannot be understood in the same way as having a [[car]] or a bank account. It means to be someone who is becoming someone—it means being a person with a past, a present, and a future. No one can have an individual's past, present or future. We all experience these in various ways—these experiences are mine, not yours or anyone else’s. Having a past, present, and future means that I am an existing individual—that I find my meaning in time and by existing. Individuals do not think themselves into existence, they are born. But once born and past a certain age, the individual begins to make choices in life; now those choices can be his, his parents’, society’s, etc. The important point is that to exist, the individual must make choices—the individual must decide what to do the next moment and on into the future. What the individual chooses and how he chooses will define who and what he is—to himself and to others. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The goal of life, according to [[Socrates]], is to know thyself. Knowing myself means being aware of who I am, what I can be and what I cannot be. The search for this self, is the task of subjectivity. This task is the most important one in life. | ||

| + | Kierkegaard considers this to be an important task and should have been obvious to the individual immediately. If I do not know who I am then I am living a lie, and living a lie, for most people is wrong. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Subjectivity comes with consciousness of myself as a self. It encompasses the emotional and intellectual resources that the individual is born with. Subjectivity is what the individual is as a human being. Now the problem of subjectivity is to decide how to choose—what rules or models is the individual going to use to make the right choices? What are the right choices? Who defines [[right]]? To be truly an individual, to be true to himself, his actions should in some way be expressed so that they describe who and what he is to himself and to others. The problem, according to Kierkegaard is that we must choose who and what we will be based on subjective interests—the individual must make choices that will mean something to him as a reasoning, feeling being. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Three Stages of Life=== | ||

| + | Kierkegaard recognized three levels of individual existence, which were the focus of [[Stages on Life's Way]]. Each of these levels of existence envelops those below it: an ethical person is still capable of aesthetic enjoyment, for example. It is also important to note that the difference between these ways of living are inward, not external, and thus there are no external signs one can point to to determine at what level a person is living. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =====Stage One: Aesthetic===== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Kierkegaard was devoted to [[aesthetics]], and is sometimes referred to as the "poet-philosopher" because of the passionate way in which he approached [[philosophy]]. But he was also devoted to showing the inadequacy of a life lived entirely on the aesthetic level. An aesthetic life is one defined by enjoyment and interest and possibilities. It is not necessarily a life lived in devotion to art—although many artists do also live at this level of existence. There are many degrees of aesthetic existence—at the bottom, one might see the purely consumerist lifestyle. At the top of this spectrum, we could find those lives which are lived in a truly [[anarchy (word)|anarchic]], irresponsible way. But Kierkegaard believes that most people live in this sphere, their lives and activities guided by enjoyment and interest rather than any truly deep and meaningful commitment to anything. Whether such people know it or not, their lives are ones of complete despair. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =====Stage Two: Ethical===== | ||

| + | The second level of existence is the ethical. This is where an individual begins to take on a true direction in life, becoming genuinely aware of [[goodness and value theory|good]] and [[evil]] and forming some absolute commitment to something. One’s actions at this level of existence have a consistency and coherence that they lacked in the previous sphere of existence. For Kierkegaard, the ethical is supremely important. It calls each individual to take account of their lives and to scrutinize their actions in terms of universal and absolute demands. | ||

| + | |||

| + | These demands are made in such a way that each individual must respond—to be authentic—in a truly committed, passionate consciousness. Any other type of response is shirking the demands of responsibility and running away from those universal duties. What responsibilities there are, are known to everyone, yet they cannot be known in such a way that they are simply followed as a matter of course. They must be done subjectively—that is, with an understanding that doing or not doing them has a direct result on who I will see myself as a person—whether a good or bad person. [[Ethics]] is something I do for myself, with the realization that my entire self-understanding is involved. The meaning of my life comes down to whether or not I live out these beliefs in an honest, passionate, and devoted way. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =====Stage Three: Religious===== | ||

| + | The ethical and the [[religious]] are intimately connected— it is important to note that one can have the ethical without religious, but the religious includes the ethical. Both ethics and religion rest on the awareness of a reality that gives substance to actions but which is not reducible to natural laws or to reason. Whereas living in the ethical sphere involves a commitment to some ethical absolute, living in the religious sphere involves a commitment to and relation to God. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Religion is the highest stage in human existence. Kierkegaard distinguishes two types within this stage, which have been called ''Religiousness A'' and ''Religiousness B''. One type is symbolized by the [[Greek philosophy|Greek philosopher]] [[Socrates]], whose passionate pursuit of the truth and individual conscience came into conflict with his society. Another type of religiousness is one characterized by the realization that the individual is [[sin]]ful and is the source of untruth. In time, through revelation and in direct relationship with the [[paradox]] that is [[Jesus]], the individual begins to see that his or her eternal salvation rests on a paradox—God, the transcendent, coming into time in human form to redeem human beings. For Kierkegaard, the very notion of this occurring was scandalous to human reason—indeed, it must be, and if it is not then one does not truly understand the [[Incarnation]] nor the meaning of human sinfulness. For Kierkegaard, the impulse towards an awareness of a transcendent power in the universe is what religion is. Religion has a social and an individual (not just personal) dimension. But it begins with the individual and his or her awareness of sinfulness. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Kierkegaard's Thoughts On Other Philosophers== | ||

| + | ===Kierkegaard and Hegel=== | ||

| + | [[Image:Hegel.jpg|150px|thumb|Hegel]] | ||

| + | One of Kierkegaard's greatest contributions to philosophy is his critique of [[Georg Hegel]]. Most of Kierkegaard's earliest works are in response to or a critique of Hegel. Although Kierkegaard opposed Hegel's philosophy and his supporters, he had the utmost respect for Hegel himself. In a journal entry made in [[1844]], Kierkegaard wrote: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Quotation|If Hegel had written the whole of his logic and then said, in the preface or some other place, that it was merely an experiment in thought in which he had even begged the question in many places, then he would certainly have been the greatest thinker who had ever lived. As it is, he is merely comic. |Søren Kierkegaard|(Journals, 1844)}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Denmark, [[Hegelianism]] was spreading in academia like a "rampant disease". [[Johan Ludvig Heiberg (poet)|Johan Ludvig Heiberg]] was a key figure in Danish Hegelianism. Kierkegaard remarked in his journal on [[17 May]][[1843]] that Heiberg's writings were "borrowed" from Hegel, implying Heiberg would have been a nobody without Hegel. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The main objection Kierkegaard had against Hegel's philosophy was the Hegelian claim that he has devised an entire system which could explain the whole of reality, with the dialectic leading the way to this whole. Hegel also dismissed Christianity as something that can be rationally explained away and absorbed into his system. Kierkegaard attempted to refute these claims by showing that there are things in the world that cannot be explained. | ||

| + | |||

| + | To refute Hegel's claim regarding Christianity, in ''[[Fear and Trembling]]'', Kierkegaard attempts to use the story of [[Abraham]] to show that there is an authority higher than that of ethics (disproving Hegel's claim that ethics is universal) and that faith cannot be explained by Hegelian ethics, (disproving Hegel's claim that Christianity can be absorbed into his system). Either way, this work reveals an inherent flaw in Hegelian ethics. | ||

| − | [[ | + | Kierkegaard also parodies the Hegelian [[dialectic]] by showing that a thesis-antithesis coming together to form a synthesis is detrimental to individuals, rather than an improvement. |

| + | |||

| + | {{Quotation|Kierkegaard's strategy was to invert this dialectic by seeking to make everything more difficult. Instead of seeing scientific knowledge as the means of human redemption, he regarded it as the greatest obstacle to redemption. Instead of seeking to give people more knowledge he sought to take away what passed for knowledge. Instead of seeking to make God and Christian faith perfectly intelligible he sought to emphasize the absolute transcendence by God of all human categories. Instead of setting himself up as a religious authority, Kierkegaard used a vast array of textual devices to undermine his authority as an author and to place responsibility for the existential significance to be derived from his texts squarely on the reader. ... Kierkegaard's tactic in undermining Hegelianism was to produce an elaborate parody of Hegel's entire system. The pseudonymous authorship, from ''[[Either/Or]]'' to ''[[Concluding Unscientific Postscript]]'', presents an inverted Hegelian dialectic which is designed to lead readers away from knowledge rather than towards it. |Søren Kierkegaard|[http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kierkegaard/#Rhet William McDonald]}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | By doing this, Hegelian critics accuse Kierkegaard of using the dialectic to disprove the dialectic, which seems somewhat contradictory and hypocritical. However, Kierkegaard would not claim the dialectic itself is bad, only the Hegelian premise that the dialectic ''would lead to a harmonious reconciliation of everything'', which Hegel called the [[Absolute]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Kierkegaardian scholars have made several interpretations of how Kierkegaard proceeds with parodying Hegel's dialectic. One of the more popular interpretations argues the aesthetic-ethical-religious stages are the triadic process Kierkegaard was talking about. See section ''Spheres of existence'' for more information. Another interpretation argues for the world-individual-will triadic process. The dialectic here is either to assert an individual's own desire to be independent and the desire to be part of a community. Instead of reconciliation of the world and the individual where problems between the individual and society are neatly resolved in the Hegelian system, Kierkegaard argues that there's a delicate bond holding the interaction between them together, which needs to be constantly reaffirmed. [[Jean-Paul Sartre]] takes this latter view and says the individual is in a constant state of reaffirming his or her own identity, else one falls into [[bad faith]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This process of reconciliation leads to a "both/and" view of life, where both thesis and antithesis are resolved into a synthesis, which negates the importance of personal responsibility and the human choice of either/or. The work ''[[Either/Or]]'' is a response to this aspect of Hegel's philosophy. A passage from that work exemplifies Kierkegaard's contempt for Hegel's philosophy: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Quotation|Marry, and you will regret it. Do not marry, and you will also regret it. Marry or do not marry, you will regret it either way. Whether you marry or you do not marry, you will regret it either way. Laugh at the stupidities of the world, and you will regret it; weep over them, and you will also regret it. Laugh at the stupidities of the world or weep over them, you will regret it either way. Whether you laugh at the stupidities of the world or you weep over them, you will regret it either way. Trust a girl, and you will regret it. Do not trust her, and you will also regret it. ... Hang yourself or do not hang yourself, you will regret it either way. Whether you hang yourself or do not hang yourself, you will regret it either way. This, gentlemen, is the quintessence of all the wisdom of life.|Søren Kierkegaard|Either/Or}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Kierkegaard and Schelling=== | ||

| + | [[Image:Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling.png|150px|thumb|Schelling]] | ||

| + | In [[1841]]-[[1842]], Kierkegaard attended the [[Berlin]] lectures of [[Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling]]. Schelling was a critic of [[Georg Hegel]] and a professor at the [[University of Berlin]]. The university started a lecture series given by Schelling in order to espouse a type of [[positive philosophy]] which would be diametrically opposed to [[Hegelianism]]. Kierkegaard was initially delighted with Schelling. Before he left Copenhagen to attend Schelling's lectures in Berlin, he wrote to his friend Peter Johannes Sprang: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Quotation|I have put my trust in Schelling and at the risk of my life I have the courage to hear him once more. It may very well blossom during the first lectures, and if so one might gladly risk one's life. |Søren Kierkegaard|(Journals, 1841)}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | At Berlin, Kierkegaard gave high praises to Schelling. In a journal entry made sometime around October or November 1841, Kierkegaard wrote this piece about Schelling's second lecture: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Quotation|I am so pleased to have heard Schelling's second lecture — indescribably! I have sighed for long enough and my thoughts have sighed within me; when he mentioned the word, "reality" in connection with the relation of philosophy to reality the fruit of my thought leapt for joy within me. I remember almost every word he said from that moment on. ... Now I have put all my hopes in Schelling!|Søren Kierkegaard|(Journals, 1841)}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | As time went on, however, Kierkegaard, as well as many in Schelling's audience, began to become disillusioned with Schelling. In a particularly insulting letter about Schelling, Kierkegaard wrote to his brother, Peter Kierkegaard: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Quotation|Schelling drivels on quite intolerably! If you want to form some idea what this is like then I ask you to submit yourself to the following experiment as a sort of self-inflicted sadistic punishment. Imagine person R's meandering philosophy, his entirely aimless, haphazard knowledge, and person Hornsyld's untiring efforts to display his learning: imagine the two combined and in addition to an impudence hitherto unequalled by any philosopher; and with that picture vividly before your poor mind go to the workroom of a prison and you will have some idea of Schelling's philosophy. He even lectures longer to prolong the torture. ... Consequently, I have nothing to do in Berlin. I am too old to attend lectures and Schelling is too old to give them. So I shall leave Berlin as soon as possible. But if it wasn't for Schelling, I would never have travelled to Berlin. I must thank him for that. ... I think I should have become utterly insane if I had gone on hearing Schelling.|Søren Kierkegaard|(Journals, [[27 February]] [[1842]])}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Kierkegaard became disillusioned with Schelling partly because Schelling shifted his focus on actuality, including a discussion on ''quid sit'' [what is] and ''quod sit'' [that is], to a more mythological, psychic-type pseudo-philosophy. Kierkegaard's last writing about Schelling's lectures was on [[4 February]] [[1842]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Although Schelling had little influence on Kierkegaard's subsequent writings, Kierkegaard's trip to Berlin provided him ample time to work on his masterpiece, [[Either/Or]]. In a reflection about Schelling in [[1849]], Kierkegaard remarked that Schelling was ''like the [[Rhine]] at its mouth where it became stagnant water — he was degenerating into a Prussian "Excellency". (Journals, January 1849)'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Kierkegaard and Schopenhauer=== | ||

| + | [[Image:Schopenhauer.jpg|150px|thumb|Schopenhauer]] | ||

| + | Kierkegaard became acquainted with [[Arthur Schopenhauer]]'s writings quite late in his life. Kierkegaard felt Schopenhauer was an important writer, but Kierkegaard disagreed on almost every point Schopenhauer made. In several journal entries made in [[1854]], a year before he died, Kierkegaard spoke highly of Schopenhauer: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Quotation|In the same way that one disinfects the mouth during an epidemic so as not to be infected by breathing in the poisonous air, one might recommend students who will have to live in Denmark in an atmosphere of nonsensical Christian optimism, to take a little dose of Schopenhauer's Ethic in order to protect themselves against infection from that malodourous twaddle.|Søren Kierkegaard|(Journals, 1854)}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | However, Kierkegaard also considered him, ''a most dangerous sign'' of things to come: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Quotation|Schopenhauer is so far from being a real pessimist that at the most he represents 'the interesting': in a certain sense he makes [[asceticism]] interesting—the most dangerous thing possible for a pleasure-seeking age which will be harmed more than ever by distilling pleasure even out of asceticism ... is by studying asceticism in a completely impersonal way, by assigning it a place in the system.|Søren Kierkegaard|(Journals, 1854)}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Kierkegaard believes Schopenhauer's ethical point of view is that the individual succeeds in seeing through the wretchedness of existence and then decides to deaden or mortify the joy of life. As a result of this complete asceticism, one reaches contemplation: the individual does this out of sympathy. He sympathizes with all the misery and the misery of others, which is to exist. Kierkegaard here is probably referring to the pessimistic nature of Schopenhauer's philosophy. One of Kierkegaard's main concerns is a suspicion of his whole philosophy: | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Quotation|After reading through Schopenhauer's Ethic one learns - naturally he is to that extent honest - that he himself is not an ascetic. And consequently he himself has not reached contemplation through asceticism, but only a contemplation which contemplates asceticism. This is extremely suspicious, and may even conceal the most terrible and corrupting voluptuous [[melancholy]]: a profound misanthropy. In this too it is suspicious, for it is always suspicious to propound an ethic which does not exert so much power over the teacher that he himself expresses. Schopenhauer makes ethics into genius, but that is of course an unethical conception of ethics. He makes ethics into genius and although he prides himself quite enough on being a genius, it has not pleased him, or nature has not allowed him, to become a genius where asceticism and mortification are concerned.|Søren Kierkegaard|(Journals, 1854)}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Little else is known about Kierkegaard's attitude to Schopenhauer. On Schopenhauer himself, Kierkegaard felt that Schopenhauer would've been patronizing. "Schopenhauer interests me very much, as does his fate in Germany. If I could talk to him I am sure he would shudder or laugh if I were to show him [my philosophy]." ''(Journals, 1854)'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | *Dru, Alexander. [[Søren Kierkegaard#The Journals of Søren Kierkegaard|The Journals of Søren Kierkegaard]], Oxford University Press, 1938. | ||

| + | *Duncan, Elmer. Søren Kierkegaard: Maker of the Modern Theological Mind, Word Books 1976, ISBN 0876804636 | ||

| + | *Garff, Joakim. Søren Kierkegaard: A Biography, Princeton University Press 2005, ISBN 069109165X. | ||

| + | *Hannay, Alastair. Kierkegaard: A Biography, Cambridge University Press, New edition 2003, ISBN 0521531810. | ||

| + | *Kierkegaard. The Concept of Anxiety, Princeton University Press, 1981, ISBN 0691020116 | ||

| + | *Kierkegaard. The Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates, Princeton University Press 1989, ISBN 0691073546 | ||

| + | *Kierkegaard. The Sickness Unto Death, Princeton University Press, 1983, ISBN 0691020280 | ||

| + | *Lippit, John. Kierkegaard and Fear and Trembling, Routledge 2003, ISBN 0415180473 | ||

| + | *Ostenfeld, Ib and Alastair McKinnon. Søren Kierkegaard's Psychology, Wilfrid Laurer University Press 1972, ISBN 0889200688 | ||

| + | *Westphal, Merold. A Reading of Kierkegaard's Concluding Unscientific Postscript, Purdue University Press 1996, ISBN 1557530904 | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===External links=== | ||

| + | *[http://www.sorenkierkegaard.org D. Anthony Storm's Commentary On Kierkegaard] | ||

| + | *[http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kierkegaard/ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Søren Kierkegaard] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Further reading== | ||

| + | ===External links=== | ||

| + | *[http://www.stolaf.edu/collections/kierkegaard/newsletter/ Søren Kierkegaard Newsletter] edited by Gordon D. Marino | ||

| + | *[[Open Directory Project]]: [http://www.dmoz.org/Society/Philosophy/Philosophers/K/Kierkegaard,_S%C3%B8ren/ Kierkegaard, Søren] | ||

| + | *[http://www.wabashcenter.wabash.edu/Internet/kierk.htm Wabash Center Internet Guide: Soren Kierkegaard] | ||

| + | *[http://sage.stolaf.edu/ Online Library Catalog at St. Olaf College; select '''Kierkegaard Library''' from the menu to search for books and articles.] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:19th century philosophy]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Christian philosophy]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Continental philosophy]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Existentialism]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Philosophical schools and traditions]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Postmodernism]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Søren Kierkegaard]] | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{credit2|Søren_Kierkegaard|45526410|Philosophy_of_Søren_Kierkegaard|43513723}} |

Revision as of 23:39, 4 April 2006

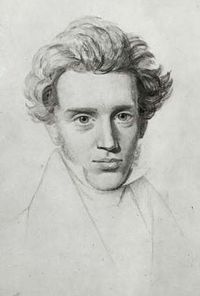

| Western Philosophers 19th-century philosophy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Name: Søren Kierkegaard | |

| Birth: 5 May, 1813 (Copenhagen, Denmark) | |

| Death: 11 November, 1855 (Copenhagen, Denmark) | |

| School/tradition: Precursor to Existentialism | |

| Main interests | |

| Religion, Metaphysics, Epistemology, Aesthetics, Ethics | |

| Notable ideas | |

| Regarded as the father of Existentialism, angst, existential despair, Three spheres of human existence, knight of faith, Subjectivity is Truth | |

| Influences | Influenced |

| Abraham, Hegel, Kant, Lessing, Socrates (through Plato, Xenophon, Aristophanes) | Jaspers, Wittgenstein, Heidegger, Sartre, Buber, Tillich, Barth, Auden, Camus, Kafka |

Søren Aabye Kierkegaard (IPA: [ˈsœːɔn ˈkʰiɔ̯g̊əˌg̊ɔːˀ]) (5 May, 1813 – 11 November, 1855), a 19th century Danish philosopher and theologian, is generally recognized as the first existentialist philosopher. He bridged the gap that existed between Hegelian philosophy and what was to become Existentialism. Kierkegaard strongly criticised both the Hegelian philosophy of his time, and what he saw as the empty formalities of the Danish church. Much of his work deals with religious problems such as the nature of faith, the institution of the Christian Church, Christian ethics and theology, and the emotions and feelings of individuals when faced with existential choices. Because of this, Kierkegaard's work is sometimes characterized as Christian existentialism and existential psychology. Kierkegaard's work resists definite interpretation, since he wrote most of his early work under various pseudonyms, and often these pseudo-authors would comment on and critique the works of his other pseudo-authors. This makes it exceedingly difficult to distinguish between what Kierkegaard truly believed and what he was merely arguing for as part of a pseudo-author's position. Ludwig Wittgenstein remarked that Kierkegaard was "by far, the most profound thinker of the nineteenth century" ([1], [2]).

Life

Early years (1813–1841)

Søren Kierkegaard was born to an affluent family in Copenhagen, the capital of Denmark. His father, Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard, was a strongly religious man. Convinced that he had earned God's wrath, he believed that none of his children would live to the age of 34. The sins necessitating this punishment, he believed, included cursing the name of God in his youth, and possibly impregnating Kierkegaard's mother out of wedlock. Though many of his seven children died young, his predictions were proved false when two of them surpassed this age. This early introduction to the notion of sin, and its connection from father and son, laid the foundation for much of Kierkegaard's work (particularly Fear and Trembling). Kierkegaard's mother, Anne Sørensdatter Lund Kierkegaard, is not directly referred to in his books, although she too affected his later writings. Despite his father's occasional religious melancholy, Kierkegaard and his father shared a close bond. Kierkegaard learned to explore the realm of his imagination through a series of exercises and games they played together.

Kierkegaard attended the School of Civic Virtue and Copenhagen University. At the university, Kierkegaard wrote his dissertation, The Concept of Irony, with Continual Reference to Socrates, which was found by the university panel to be a noteworthy and well-thought out work, but a little too wordy and literary for a philosophy thesis. Kierkegaard graduated in October 1841.

Regine Olsen (1837–1841)

Another important aspect of Kierkegaard's life (generally considered to have had a major influence on his work) was his broken engagement to Regine Olsen (1822 - 1904). Kierkegaard met Regine in 8 May, 1837 and was instantly attracted to her, and she to him. In his journals, Kierkegaard wrote about his love for Regine:

Thou sovereign of my heart treasured in the deepest fastness of my chest, in the fullness of my thought, there ... unknown divinity! Oh, can I really believe the poet's tales, that when one first sees the object of one's love, one imagines one has seen her long ago, that all love like all knowledge is remembrance, that love too has its prophecies in the individual. ... it seems to me that I should have to possess the beauty of all girls in order to draw out a beauty equal to yours; that I should have to circumnavigate the world in order to find the place I lack and which the deepest mystery of my whole being points towards, and at the next moment you are so near to me, filling my spirit so powerfully that I am transfigured for myself, and feel that it's good to be here.

Søren Kierkegaard, Journals, 2 February, 1839

On 8 September, 1840, Kierkegaard formally proposed to Regine. However, Kierkegaard soon felt disillusioned and melancholic about the marriage. Less than a year after he had proposed, he broke it off on 11 August, 1841. Several theories have been offered to explain, but Kierkegaard's motive for ending the engagement remains mysterious. It is generally believed that the two were deeply in love, perhaps even after she married Johan Frederik Schlegel (1817–1896), a prominent civil servant (not to be confused with the German philosopher Friedrich von Schlegel, 1772-1829). For the most part, their contact was limited to chance meetings on the streets of Copenhagen. Some years later, however, Kierkegaard went so far as to ask Regine's husband for permission to speak with her, but was refused.

Soon afterwards, the couple left the country, Schlegel having been appointed Governor in the Danish West Indies. By the time Regine returned, Kierkegaard was dead. Regine Schlegel lived until 1904, and upon her death she was buried near Kierkegaard in the Assistens Cemetery in Copenhagen.

The First Authorship (1841 – 1846)

Although Kierkegaard wrote a few articles on politics, women, and entertainment in his youth and university days, many scholars believe Kierkegaard's first noteworthy work is either his university thesis, The Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates, which was presented in 1841 or his masterpiece and arguably greatest work, Either/Or, which was published in 1843. In either case, both works critiqued major figures in Western philosophic thought (Socrates in the former and Hegel in the latter), showcased Kierkegaard's unique style of writing, and displayed a maturity in writing from his works of youth. Either/Or was mostly written during Kierkegaard's stay in Berlin and was completed in the autumn of 1842. The work was published in February 1843.

In the same year Either/Or was published, Kierkegaard found out Regine was engaged to be married to Johan Frederik Schlegel. This fact affected Kierkegaard and his subsequent writings deeply. In Fear and Trembling, published in late 1843, one can interpret a section in the work as saying: 'Kierkegaard hopes that through a divine act, Regine would return to him'. Repetition, published on the same day and year as Fear and Trembling, is about a young gentleman leaving his beloved. Several other works in this period make similar overtones of the Kierkegaard-Olsen relationship.

Other major works in this period focuses on a critique of Georg Hegel and form a basis for existential psychology. Philosophical Fragments, The Concept of Dread, and Stages on Life's Way are about thoughts and feelings an individual may face in life, existential choices and its consequences, and whether or not to embrace religion, specifically Christianity, in one's life. Perhaps the most valiant attack on Hegelianism is the Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments which discusses the importance of the individual, subjectivity as truth, and countering the Hegelian claim that the Rational is the Real and the Real is the Rational.

The Corsair Affair (1845–1846)

On 22 December, 1845, Peder Ludvig Møller published an article critiquing Stages on Life's Way. The article gave Stages a poor review, but showed little understanding of the work. Møller was also a contributor of The Corsair, a Danish satirical paper that lampooned people of notable standing. Kierkegaard wrote a response in order to defend the work, ridicule Møller, and bring down The Corsair, earning him the ire of the paper and its editor, Meïr Aaron Goldschmidt.

The only two articles that Kierkegaard wrote in response to The Corsair were Activity of a Traveling Esthetician and Dialectical Result of a Literary Police Action. The former focused on insulting Møller's integrity and responding to his critique. The latter was a directed assault on The Corsair, in which Kierkegaard openly asked to be satirized.

With a paper like The Corsair, which hitherto has been read by many and all kinds of people and essentially has enjoyed the recognition of being ignored, despised, and never answered, the only thing to be done in writing in order to express the literary, moral order of things—reflected in the inversion that this paper with meager competence and extreme effort has sought to bring about—was for someone immortalized and praised in this paper to make application to be abused by the same paper ... May I asked to be abused—the personal injury of being immortalized by The Corsair is just too much.

Søren Kierkegaard, Dialectical Result of a Literary Police Action

Over the next few months, The Corsair took Kierkegaard up on his offer to "be abused", and unleashed a series of attacks making fun of Kierkegaard's appearance, voice, and habits. For months, he was harassed on the streets of Denmark. In an 1846 journal entry, Kierkegaard makes a long, detailed explanation of his attack on Møller and The Corsair, and also explains that this attack made him quit his indirect communication authorship:

The days of my authorship are past, God be praised. I have been granted the satisfaction of bringing it to a conclusion [by] myself, understanding when it is fitting that I should make an end, and next after the publication of Either/Or I thank God for that. That this, once again, is not how people would see it, that I could actually prove in two words that it is so. I know quite well and find [my authorship] quite in order. But it has pained me; it seemed to me that I might have asked for that admission; but let it be. If only I can manage to become a priest. However much of my present life may have satisfied me: I shall breathe more freely in that quiet activity, allowing myself an occasional literary work in my free time.

Søren Kierkegaard, Journals, 9 March, 1846

The Second Authorship (1846–1853)

Whereas his first authorship focused on Hegel, this authorship focused on the hypocrisy of Christendom. It is important to realise that by 'Christendom' is not meant Christianity itself, but rather the church and the applied religion of his society. After the Corsair incident, Kierkegaard became interested in "the public" and the individual's interaction with it. His first work in this period of his life was Two Ages: A Literary Review which was a critique of the novel Two Ages (in some translations Two Generations) written by Thomasine Christine Gyllembourg-Ehrensvärd. After giving his critique of the story, Kierkegaard made several insightful observations on the nature of the present age and its passionless attitude towards life.

The present age is essentially a sensible, reflecting age, devoid of passion, flaring up in superficial, short-lived enthusiasm and prudentially relaxing in indolence. ... whereas a passionate age accelerates, raises up, and overthrows, elevates and debases, a reflective apathetic age does the opposite, it stifles and impedes, it levels. In antiquity the individual in the crowd had no significance whatsoever; the man of excellence stood for them all. The trend today is in the direction of mathematical equality, so that in all classes about so and so many uniformly make one individual.... For leveling to take place, a phantom must first be raised, the spirit of leveling, a monstrous abstraction, an all-encompassing something that is nothing, a mirage—and this phantom is the public.... The present age is essentially a sensible age, devoid of passion and therefore it has nullified the principle of contradiction.

Søren Kierkegaard, (Two Ages)

Other works continue to focus on the superficiality of "the crowd" attempting to limit and stifle the unique individual. The Book on Adler is a work about Pastor Adolf Peter Adler's claim to have had a sacrilegious revelation and was shunned and expelled from the pastorate.

As part of his analysis of the crowd, Kierkegaard realized the decay and decadence of the Christian church, especially the Danish State Church. Kierkegaard believed Christendom had "lost its way" on the Christian faith. Christendom in this period ignored, skewed, and gave 'lip service' to the original Christian doctrine. Kierkegaard felt his duty in this later era was to inform others about the shallowness of so-called "Christian living". He wrote several criticisms on contemporary Christianity in works such as Christian Discourses, Works of Love, and Edifying Discourses in Diverse Spirits.

The Sickness Unto Death is one of Kierkegaard's most popular works in this era, and although some contemporary atheistic philosophers and psychologists dismiss Kierkegaard's suggested solution as faith, his analysis on the nature of despair is one of the best accounts on the subject and has been emulated in subsequent philosophies, such as Heidegger's concept of existential guilt and Sartre's bad faith.

Around 1848, Kierkegaard began a literary attack on the Danish State Church with books such as Practice in Christianity, For Self-Examination, and Judge for Yourselves!, which attempted to expound the true nature of Christianity, with Jesus as the role model.

Attack Upon Christendom (1854–1855)

Kierkegaard's final years were taken up with a sustained, outright attack on the Danish State Church by means of newspaper articles published in The Fatherland (Fædrelandet) and a series of self-published pamphlets called The Moment (Øieblikket). Kierkegaard was initially called to action by a speech by Professor Hans Lassen Martensen, which called his recently deceased predecessor Bishop Jakob P. Mynster a "truth-witness, one of the authentic truth-witnesses."

Kierkegaard had an affection towards Mynster, but had come to see that his conception of Christianity was in man's interest, rather than God's, and in no way was Mynster's life comparable to that of a 'truth-witness.'

Before the tenth chapter of The Moment could be published, Kierkegaard collapsed on the street and was taken to a hospital. He stayed in the hospital for nearly a month and refused to receive communion from a priest of the church, whom Kierkegaard regarded as merely an official and not a servant of God.

He said to his friend since boyhood Emil Boesen, who kept a record of his conversations and was himself a pastor, that his life had been one of great and unknown suffering, which looked like vanity to others but was not.

Kierkegaard died in Frederick's Hospital after being there for over a month, possibly from complications from a fall he had taken from a tree when he was a boy. He was interred in the Assistens Kirkegård in the Nørrebro section of Copenhagen. At Kierkegaard's funeral, his nephew Henrik Lund caused a disturbance by protesting that Kierkegaard was being buried by the official church even though in his life he had broken from and denounced it. Lund was later fined.

Kierkegaard's Thought

Kierkegaard is labelled a Christian existentialist, a theologian, the father of existentialism, a psychologist, a poet and a philosopher. Two of his main ideas are the "leap of faith" and "subjectivity". The leap of faith is his conception of how an individual would believe in God, or how a person would act in love. It is not so much a rational decision, as it is a rejection of rationality in favour of something more uncanny, that is, faith. As such he thought that to have faith is at the same time to have doubt. So, for example, for one to truly have faith in God, one would also have to doubt that God exists; the doubt is the rational part of a person's thought, without which the faith would have no real substance. Doubt is an essential element of faith, an underpinning. In plain words, to believe or have faith that God exists, without ever having doubted God's existence or goodness, would not be a faith worth having. For example, it takes no faith to believe that a pencil or a table exists, when one is looking at it and touching it. In the same way, to believe or have faith in God is to know that one has no perceptual or any other access to God, and yet still has faith in God.

Kierkegaard also stressed the importance of the self, and the self's relation to the world as being grounded in self-reflection and introspection. He argued in Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments that "subjectivity is truth" and "truth is subjectivity"; that is, that the self is the ultimate governor of what life is and what life means. He also believed in the infinity of the self, explaining that the self could not be fully known or understood, because it is infinite. In this way his thought reflects the Christian idea of the soul, which is immortal; but Kierkegaard was not speaking about the immortality of the self as much as the depth of the soul, of a person's being.

His writings, many of which were written pseudonymously, reflected not only the trend at the time to write pseudonymously but also his idea that a person or a self is made up of many faces and facets, as his book titled Philosophical Fragments would indicate. Kierkegaard did not like the systems that were brought on by philosophers such as Kant and Hegel before him. He measured himself against the backdrop of philosophy which was introduced by Socrates, as he noted in Concluding Unscientific Postscript, and preferred a philosophy that was fragmented and made deep insights, without committing to an encompassing all-explaining system.

Indirect communication and pseudonymous authorship

During Søren Kierkegaard's early authorship, he frequently wrote many of his works under various pseudonyms who represented different ways of thinking and living. This was part of Kierkegaard's indirect communication technique. According to several passages in his works and his journals, such as The Point of View of my Work as an Author, Kierkegaard wrote this way in order to prevent his works from being treated as a philosophical system with a systematic structure. In the Point of View, Kierkegaard wrote: "In the pseudonymous works, there is not a single word which is mine. I have no opinion about these works except as a third person, no knowledge of their meaning, except as a reader, not the remotest private relation to them."

Writing this way was intended to make it difficult to ascertain whether a viewpoint put forward by a pseudonym is a viewpoint actually held by Kierkegaard or not. Kierkegaard hoped readers would just read the work at face value, without attributing it to some aspect of his life. Kierkegaard thought he was able to write on various aspects of the aesthetic, ethical and religious stages of life, while his pseudonyms prevented readers from seeing all of this as one unified system.

Kierkegaard also did not want his readers to treat his work as authoritative. He wanted his readers to look to themselves for interpreting his work. Early Kierkegaardian scholars, such as Theodor W. Adorno, have disregarded Kierkegaard's intentions and argues that the entire authorship should be treated as Kierkegaard's own personal and religious views. This way of looking at Kierkegaard's work leads to many confusions and seeming contradictions, which makes Kierkegaard seem like an incoherent writer ([3]). However, many later scholars, such as the post-structuralists, have respected Kierkegaard's wishes and intentions and interpreted his work by attributing the pseudonymous texts to their respective authors.

Some of Kierkegaard's most important pseudonyms include:

- Victor Eremita, editor of Either/Or

- A, writer of many articles in Either/Or

- Judge William, author of rebuttals to A in Either/Or

- Anti-Climacus, author of The Sickness Unto Death

- Johannes de Silentio, author of Fear and Trembling

- Hilarius Bookbinder, editor of Stages on Life's Way

- Vigilius Haufniensis, author of The Concept of Dread

- Johannes Climacus, author of Philosophical Fragments and Concluding Unscientific Postscript

The Journals of Søren Kierkegaard

One of group of key texts in attempting to understand Kierkegaard and his work are his journals. [4] Kierkegaard wrote over 7000 pages in his journals describing key events, musings, thoughts about his works and everyday remarks. The entire collection of Danish journals has been edited and published in 13 volumes, which consist of 25 separate bindings, including indices. The first English edition of the journals was edited by Alexander Dru in 1938 ([5]).

His journals reveal many different facets of the man and his work and help elucidate many of his ideas. Scholars have frequently noted the style in his journals is among the most elegant and poetic of his writings. Kierkegaard took his journals quite seriously and even remarked in one passage that it was his most trusted confidant:

I have never confided in anyone. By being an author I have in a sense made the public my confidant. But in respect of my relation to the public I must, once again, make posterity my confidant. The same people who are there to laugh at one cannot very well be made one's confidant.

Søren Kierkegaard, (Journals, 4 November, 1847)

His journals have also been the source of many aphorisms credited to Kierkegaard. The following passage is perhaps one of the most oft-quoted aphorism from Kierkegaard's journals and is usually a key quote for existentialist studies:

The thing is to find a truth which is true for me, to find the idea for which I can live and die.

Søren Kierkegaard, (Journals, 1 August, 1835)

Although his journals clarify some aspects of his work and life, Kierkegaard made note not to reveal too much. Abrupt changes in thought, repetitive writing, unusual turns of phrases are among many of the tactics Kierkegaard uses to throw readers of the track and lead to many variations of interpretations of his journals. However, Kierkegaard did not doubt the importance his journals would have in the future. In 1849, Kierkegaard wrote:

Only a dead man can dominate the situation in Denmark. Licentiousness, envy, gossip, and medocrity are everywhere supreme. Were I to die now the effect of my life would be exceptional; much of what I have simply jotted down carelessly in the Journals would become of great importance and have a great effect; for then people would have grown reconciled to me and would be able to grant me what was, and is, my right.

Søren Kierkegaard, (Journals, December 1849)

Kierkegaard and Christendom

As mentioned in the biography, during the final years of his life, Kierkegaard took up a sustained attack on all of Christendom, Christanity as a political entity. In the 19th century, most Danes who were citizens of Denmark were necessarily members of the Danish State Church. In 2002 even, the Church of Denmark reports 84.3% of Danes are members of the state church [6]. Kierkegaard felt this state-church union was unacceptable and perverted the true meaning of Christianity. The main points of the attack include:

- Church congregations are meaningless: The idea of congregations keeps individuals as children since it disinclines Christians from taking the initiative to take responsibility for their own relation to God. Kierkegaard stresses that "Christianity is the individual, here, the single individual." [7]

- Christendom had become secularized and political: Since the Church was controlled by the State, Kierkegaard believed it was the State's bureacratic mission to increase membership and oversee the welfare of its members. More members would mean more power for the clergymen: a corrupt ideal. This mission would seem at odds with Christianity's true doctrine, which is to stress the importance of the individual, not the whole.

- Christianity becomes an empty religion: Thus, the state church political structure is offensive and detrimental to individuals, since everyone can become "Christian" without knowing what it means to be Christian. It is also detrimental to the religion itself since it reduces Christianity to a mere fashionable tradition adhered to by unbelieving "believers", a "herd mentality" of the population, so to speak.

If the Church is "free" from the state, it's all good. I can immediately fit in this situation. But if the Church is to be emancipated, then I must ask: By what means, in what way? A religious movement must be served religiously - otherwise it is a sham! Consequently, the emancipation must come about through martyrdom - bloody or bloodless. The price of purchase is the spiritual attitude. But those who wish to emancipate the Church by secular and worldly means (i.e. no martyrdom), they've introduced a conception of tolerance entirely consonant with that of the entire world, where tolerance equals indifference, and that is the most terrible offence against Christianity. ... the doctrine of the established Church, its organization, are both very good indeed. Oh, but then our lives: believe me, they are indeed wretched.

Søren Kierkegaard, (Journals, January 1851)

Because of the incompetence and corruption of the Christian churches, Kierkegaard seemed to have foreseen philosophers like Nietzsche who would go on to criticize the Christian religion.

I ask: what does it mean when we continue to behave as though all were as it should be, calling ourselves Christians according to the New Testament, when the ideals of the New Testament have gone out of life? The tremendous disproportion which this state of affairs represents has, moreover, been perceived by many. They like to give it this turn: the human race has outgrown Christianity.

Søren Kierkegaard, (Journals, June 19, 1852)

Criticisms of Kierkegaard

Some of Kierkegaard's famous philosophical critics in the 20th century include Theodor Adorno and Emmanuel Levinas. Atheistic philosophers such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Heidegger mostly support Kierkegaard's philosophical views, but criticize and reject his religious views.

Adorno's take on Kierkegaard's philosophy has been less than faithful to the original intentions of Kierkegaard. At least one critic of Adorno considers his book Kierkegaard: Construction of the Aesthetic to be "the most irresponsible book ever written on Kierkegaard" because Adorno takes Kierkegaard's pseudonyms literally, and constructs an entire philosophy of Kierkegaard which makes him seem incoherent and unintelligible. This is like confusing William Shakespeare with Othello and Dostoevsky with Raskolnikov [8]. Another reviewer mentions that "Adorno is [far away] from the more credible translations and interpretations of the Collected Works of Kierkegaard we have today" ([9]).

Levinas' main attack on Kierkegaard is focused on his ethical and religious stages, especially in Fear and Trembling. Levinas criticizes the leap of faith by saying this suspension of the ethical and leap into the religious is a type of violence. [10]

Kierkegaardian violence begins when existence is forced to abandon the ethical stage in order to embark on the religious stage, the domain of belief. But belief no longer sought external justification. Even internally, it combined communication and isolation, and hence violence and passion. That is the origin of the relegation of ethical phenomena to secondary status and the contempt of the ethical foundation of being which has led, through Nietzsche, to the amoralism of recent philosophies.

Emmanuel Levinas, Existence and Ethics, (1963)

Levinas points to the fact that it was God who first commanded Abraham to sacrifice Isaac and that it was an angel who commanded Abraham to stop. If Abraham was truly in the religious realm, he would not have listened to the angel to stop and should have continued to kill Isaac. "Transcending ethics" seems like a loophole to excuse would-be murders from their crime and thus is unacceptable ([11]).

On Kierkegaard's religious views, Sartre offers the usual argument against existence of God: If existence precedes essence, it follows from the meaning of the term sentient that a sentient being cannot be complete or perfect. In Being and Nothingness, Sartre's phrasing is that God would be a pour-soi [a being-for-itself; a consciousness] who is also an en-soi [a being-in-itself; a thing]: which is a contradiction in terms.

Sartre agrees with Kierkegaard's analysis of Abraham undergoing anxiety (Sartre calls it anguish), but Sartre doesn't agree that God told him to do it. In his lecture, Existentialism is a Humanism, he says:

The man who lies in self-excuse, by saying "Everyone will not do it" must be ill at ease in his conscience, for the act of lying implies the universal value which it denies. By its very disguise his anguish reveals itself. This is the anguish that Kierkegaard called "the anguish of Abraham." You know the story: An angel commanded Abraham to sacrifice his son; and obedience was obligatory, if it really was an angel who had appeared and said, "Thou, Abraham, shalt sacrifice thy son." But anyone in such a case would wonder, first, whether it was indeed an angel and secondly, whether I am really Abraham. Where are the proofs? A certain mad woman who suffered from hallucinations said that people were telephoning to her, and giving her orders. The doctor asked, "But who is it that speaks to you?" She replied: "He says it is God." And what, indeed, could prove to her that it was God? If an angel appears to me, what is the proof that it is an angel; or, if I hear voices, who can prove that they proceed from heaven and not from hell, or from my own subconsciousness or some pathological condition? Who can prove that they are really addressed to me?

Jean-Paul Sartre, ([12]) Existentialism is a Humanism

Kierkegaard would have said that this requirement for "proof that it is God" relies on reason alone, and Kierkegaard believes that faith in God transcends "reason alone" by recognizing that human beings have reason because they are created by God in God's image.

Kierkegaard's influence

Kierkegaard's works were not made widely available until several decades after his death. This is perhaps due to the facts that Kierkegaard was shunned by the Danish State Church, one of the major institutions in Denmark at the time, as well as the relative obscurity of the Danish language, compared to languages such as German and English. Georg Brandes, an early Kierkegaardian Danish scholar who was fluent in Danish and German, gave one of the first formal lectures on Kierkegaard and helped bring Kierkegaard to the attention of Europe. Brandes also wrote the first book on Kierkegaard's philosophy and life in 1877. The dramatist Henrik Ibsen became interested in Kierkegaard and introduced the works in Scandinavia. German translations appeared during the 1910s, while the first English translations were produced in 1938 by Alexander Dru under the editorial efforts of then-Oxford University Press editor Charles Williams[13]. Kierkegaard's fame as a philosopher grew tremendously in the 1930s, mostly in response to the growing existentialist movement.

Many 20th-century philosophers, both theistic and atheistic, drew many concepts from Kierkegaard, including the notions of angst, despair, and the importance of the individual. Philosophers and theologians who have been influenced by Kierkegaard include Karl Jaspers, Paul Tillich, Rudolf Karl Bultmann, Martin Buber, Gabriel Marcel, Miguel de Unamuno, Karl Barth, Hans Urs von Balthasar, Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, and Simone de Beauvoir. Paul Feyerabend's scientific anarchism was inspired by Kierkegaard's idea of subjectivity as truth. Ludwig Wittgenstein has been known to have been immensely influenced and humbled by Kierkegaard [14], claiming that "Kierkegaard is far too deep for me, anyhow. He bewilders me without working the good effects which he would in deeper souls" ([15]).

Kierkegaard's literary influence has also been considerable; those deeply affected by his work include Walker Percy, David Lodge, and John Updike.

Kierkegaard also had a profound influence on psychology and created the foundations of Christian psychology, existential psychology and therapy. Ludwig Binswanger, Victor Frankl, and Carl Rogers are well-known existential or humanistic psychologists. Rollo May, an American existential psychologist, based his work The Meaning of Anxiety on Kierkegaard's The Concept of Anxiety. Kierkegaard's sociological work Two Ages: The Age of Revolution and the Present Age provides an interesting critique of modernity. Kierkegaard is also an important figure in postmodernism.

Kierkegaard himself had accurately predicted his own posthumous fame in his journals. He foresaw that his work would become the subject of intense study and research. In his journals, he writes:

What the age needs is not a genius - it has had geniuses enough, but a martyr, who in order to teach men to obey would himself be obedient unto death. What the age needs is awakening. And therefore someday, not only my writings but my whole life, all the intriguing mystery of the machine will be studied and studied. I never forget how God helps me and it is therefore my last wish that everything may be to his honour

Søren Kierkegaard, (Journals, 20 November, 1847)

Selected bibliography

For a complete bibliography, see List of Works by Søren Kierkegaard

- (1841) The Concept of Irony (Om Begrebet Ironi med stadigt Hensyn til Socrates)

- (1843) Either/Or (Enten - Eller)

- (1843) Fear and Trembling (Frygt og Bæven)

- (1843) Repetition (Gjentagelsen)

- (1844) Philosophical Fragments (Philosophiske Smuler)

- (1844) The Concept of Dread (Begrebet Angest)

- (1845) Stages on Life's Way (Stadier paa Livets Vei)

- (1846) Concluding Unscientific Postscript to The Philosophical Fragments (Afsluttende uvidenskabelig Efterskrift)