Difference between revisions of "Pygmy" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (48 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Anthropology]] | [[Category:Anthropology]] | ||

| − | {{ | + | [[Category:Ethnic group]] |

| − | + | {{Paid}}{{approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{copyedited}} | |

| + | |||

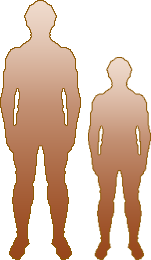

| + | [[Image:Pygmy.png|thumb|right|200px|Comparative height of a Pygmy man (right) and a European man (left).]] | ||

| + | In [[anthropology]], a '''Pygmy''' is a member of a [[hunter-gatherer]] people characterized by short stature. They are found in central [[Africa]] as well as parts of southeast [[Asia]]. Pygmy [[tribe]]s maintain their own [[culture]] according to their own [[belief]]s, [[tradition]]s, and [[language]]s, despite interaction with neighboring tribes and various colonists. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | The greatest threats to Pygmy survival in Africa comes from threatened loss of habitat due to extensive logging of the [[rainforest]]s, and spread of [[disease]]s such as [[AIDS]] from neighboring tribes who regard them as subhuman. | ||

| − | + | ==Definition== | |

| − | In an [[anthropology|anthropological]] context, a '''Pygmy''' is specifically a member of one of the [[hunter-gatherer]] people living in [[equatorial rainforest]]s, | + | Generally speaking, '''pygmy''' can refer to any human or animal of unusually small size (e.g. [[pygmy hippopotamus]]). In an [[anthropology|anthropological]] context, however, a '''Pygmy''' is specifically a member of one of the [[hunter-gatherer]] people living in [[equatorial rainforest]]s, characterized by their short height (less than 4.5 feet, on average). Pygmies are found throughout central [[Africa]], with smaller numbers in south-east [[Asia]], [[New Guinea]], and the [[Philippines]]. Members of so-called Pygmy groups often consider the term derogatory, instead preferring to be called by the name of their [[ethnic group]] (for example, Baka or Mbuti). The terms "forest foragers," "forest dwellers," and "forest people" have also been used, but, for lack of an alternative, "Pygmy" remains the predominant term used throughout scientific circles. |

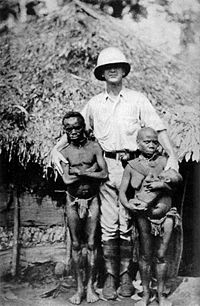

| + | [[Image:African_Pigmies_CNE-v1-p58-B.jpg|right|200px|thumb|African pygmies and a European explorer.]] | ||

| + | Pygmies are smaller because in early [[adolescence]] they do not experience the growth spurt normal in most other humans. [[Endocrinology|Endocrinologists]] consider low levels of [[growth hormone]] binding [[protein]]s to be at least partially responsible for the Pygmies' short stature.<ref> G. Baumann, M.A. Shaw, and T.J. Merimee, [http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/abstract/320/26/1705 Low levels of high-affinity growth hormone-binding protein in African pygmies.] Retrieved August 4, 2018. </ref> | ||

| − | Pygmies are | + | ==Pygmy References in History== |

| − | + | The Pygmies are thought to be the first inhabitants of the [[Africa]]n continent. The earliest reference to Pygmies is inscribed on the tomb of Harkuf, an explorer for the young King Pepi II of [[Ancient Egypt]]. The text is from a letter sent from Pepi to Harkuf around 2250 B.C.E., which described the boy-king's delight at hearing that Harkuf would be bringing back a pygmy from his expedition, urging him to take particular care, exclaiming, "My Majesty longs to see this pygmy more than all the treasure of Sinai and Punt!"<ref> Eric H. Cline and Jill Rubalcaba, ''The Ancient Egyptian World'' (Oxford University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0195222449). </ref> References are also made to a pygmy brought to Egypt during the reign of King Isesi, approximately 200 years earlier. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Later, more [[mythology|mythological]] references to Pygmies are found in the Greek literature of [[Homer]], [[Herodotus]], and [[Aristotle]]. Homer described them as: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>Three-Span (Trispithami) Pygmae who do not exceed three spans, that is, twenty-seven inches, in height; the climate is healthy and always spring-like, as it is protected on the north by a range of mountains; this tribe Homer has also recorded as being beset by cranes. It is reported that in springtime their entire band, mounted on the backs of rams and she-goats and armed with arrows, goes in a body down to the sea and eats the cranes' eggs and chickens, and that this outing occupies three months; and that otherwise they could not protect themselves against the flocks of cranes would grow up; and that their houses are made of mud and feathers and egg-shells (Pliny Natural History 7.23-29). </blockquote> | |

| − | + | Aristotle also wrote of Pygmies, stating that they came from the "marshlands south of Egypt where the Nile has its source." He went on to state that the existence of the Pygmies is not fiction, "but there is in reality a race of dwarfish men, and the horses are little in proportion, and the men live in caves underground." | |

| − | In 1904, an American explorer | + | In 1904, Samual Verner, an American explorer, was hired by the St. Louis World's Fair to bring back African pygmies for exhibition. Afterwards, he took the Africans back to their country. One Pygmy, named Ota Benga, returned to find that his entire [[tribe]] had been wiped out during his absence, and asked Verner to take him back to the [[United States]]. In September of 1906, he became part of a new exhibit at the Bronx Zoo, and was displayed in a cage in the Monkey House. The exhibit attracted up to forty thousand visitors a day, and sparked a vehement protest from African American ministers. Attempts to help Ota Benga live a normal life failed in March of 1916, when the African borrowed a gun from his host family, went into the woods, and shot himself.<ref> NPR, [http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5787947 From the Belgian Congo to the Bronx Zoo.] Retrieved August 4, 2018. </ref> |

==African Pygmies== | ==African Pygmies== | ||

| + | [[Image:Pygmy_house_inside_fire.JPG|left|250px|thumb|Inside view of Pygmy house northern Republic of the Congo]] | ||

| − | There are many African Pygmy tribes throughout central Africa, including the [[Mbuti]], [[Bayaka |Aka]], [[BaBenzelé]], [[Baka | + | There are many African Pygmy tribes throughout central [[Africa]], including the [[Mbuti]], [[Bayaka|Aka]], [[BaBenzelé]], [[Baka]], [[Efé]], [[Twa]] (also known as Batwa), and [[Wochua]]. Most Pygmies are [[nomad]]ic, and obtain their food through a mix of foraging, [[hunting]], [[fishing]], and [[trade|trading]] with inhabitants of neighboring villages. Their cultural identity is very closely tied to the rainforest, as are their spiritual and [[religion|religious]] views. [[Music]], as well as [[dance]], is an important aspect of Pygmy life, and features various instruments and intricate vocal polyphony. |

| − | + | Pygmies are often romantically portrayed as both [[utopia]]n and "pre-modern," which overlooks the fact that they have long had relationships with more "modern" non-Pygmy groups (such as inhabitants of nearby villages, agricultural employers, logging companies, evangelical missionaries, and commercial hunters.) It is often said that Pygmies have no language of their own, speaking only the language of neighboring villagers, but this is not true. Both the Baka and Bayaka (also known as the Aka), for example, have their own unique language distinct from that of neighboring villagers; the Bayaka speak Aka amongst themselves, but many also speak the Bantu language of the villagers.<ref> Daniel Duke, Aka as a Contact Language: Sociolinguistic and Grammatical Evidence. </ref> Two of the more studied tribes are the [[Pygmy#The Baka|Baka]] and the [[Pygmy#The Mbuti|Mbuti]], who were the subject of the well known book ''The Forest People'' (1962) by [[Colin Turnbull]]. | |

| − | + | [[Image:Pygmy_house_outsideview.JPG|right|250px|thumb|Pygmy houses made with sticks and leaves in northern Republic of the Congo]] | |

| − | |||

| − | The | + | ===The Baka=== |

| + | The '''Baka''' Pygmies inhabit the rain forests of [[Cameroon]], [[Congo]], and [[Gabon]]. Because of the difficulty in determining an accurate number, population estimates range from 5,000 to 28,000 individuals. Like other Pygmy groups, they have developed a remarkable ability to use all that the forest has to offer. | ||

| − | + | They live in relative symbiosis with neighboring Bantu farmers, [[trade|trading]] goods and services for that which cannot be obtained from the forest. The Baka speak their own language, also called Baka, as well as the language of neighboring Bantu. Most adult men also speak French and Lingala, the main [[lingua franca]] of central Africa.<ref> Daiji Kimura, Utterance Overlap and Long Silence Among the Baka Pygmies: Comparison with Bantu Farmers and Japanese University Students.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | ====Lifestyle==== |

| + | The Baka traditionally live in single family huts called ''mongulu,'' made of branches and leaves and built predominantly by women, although more and more rectangular homes, like those of their Bantu neighbors, are being built. [[Hunting]] is one of the most important activities in Baka culture; not only for the food it provides (as many Baka live mainly by [[fishing]] and gathering), but also because of the prestige and [[symbol]]ic meaning attached to the hunt. The Baka use bows, poisoned arrows, and traps to hunt game, and are well versed in the use of plants for medicine as well as poison. | ||

| − | + | Like most Pygmy groups, they move to follow the available food supply. When not camped in their permanent camp, the Baka rarely stay in one spot for longer than one week. During the rainy season, the Baka go on long expeditions into the forest to search for the wild [[mango]], or ''peke,'' in order to produce a valued and delicious oil paste.<ref> Laurent Maget and Baptiste Bouleau, [https://news.cnrs.fr/slideshows/a-mango-harvest-with-the-baka-pygmies A Mango Harvest with the Baka Pygmies] ''CNRS News'', May 11, 2016. Retrieved August 4, 2018. </ref> | |

| − | + | ====Social Structure and Daily Life==== | |

| + | In Baka society, men and women have fairly defined roles. Women build the huts, or ''mongulus,'' and dam small streams to catch [[fish]]. When the Baka roam the forest, women carry their few possessions and follow their husbands. Baka men have the more prestigious (and hazardous) task of [[hunting]] and trapping. | ||

| − | + | The Baka have no specific [[marriage]] ceremonies. The man builds a mud house for himself and his future wife and then brings gifts to his intended's parents. After that they live together but are not considered a permanent couple until they have children. Unlike nearby Bantu, the Baka are not [[polygamy|polygamists]].<ref>[https://kwekudee-tripdownmemorylane.blogspot.com/2013/08/baka-pygmy-people-renowned-pygmy-people.html Baka (Pygmy) People] ''Trip Down Memory Lane'', August 15, 2013. Retrieved August 4, 2018.</ref> | |

| + | [[Image:Marquardt & Baka dancers.jpg|thumb|left|250 px|Baka dancers in the East Province of Cameroon, June 2006.]] | ||

| + | [[Music]] plays an integral role in Baka society. As with other Pygmy groups, Baka music is characterized by complex vocal polyphony, and, along with [[dance]], is an important part of healing [[ritual]]s, [[initiation]] rituals, group games and tales, and pure entertainment. In addition to traditional instruments like the [[flute]], floor standing bow, and musical bow (which is played exclusively by women), the Baka also use instruments obtained from the Bantu, such as cylindrical [[drum]]s and the harp-zither.<ref> Mauro Campagnoli, [http://www.pygmies.info/baka/music.html Baka Pygmies—Music and Musical Instruments.] Retrieved August 4, 2018. </ref> As a result of the influence of visiting European musicians, some Baka have formed a band and released an album of music, helping to spread cultural awareness and protect the forest and the Baka culture.<ref> BBC, [http://www.bbc.co.uk/tyne/content/articles/2006/04/07/roots_baka_feature.shtml Who are the Baka Pygmies? And What are They Doing in Gateshead?] Retrieved August 4, 2018.</ref> | ||

| − | + | The rite of initiation into manhood is one of the most sacred parts of a male Baka's life, the details of which are kept a closely guarded secret from both outsiders and Baka women and children. Italian [[ethnology|ethnologist]] Mauro Campagnoli had the rare opportunity to take part in a Baka initiation, and is one of the only white men to officially become a part of a Baka tribe. The initiation takes place in a special hut deep in the forest, where they eat and sleep very little while undergoing a week long series of rituals, including public dances and processions as well as more secret and dangerous rites. The initiation culminates in a rite where the boys come face to face with the Spirit of the Forest, who "kills" them and then brings them back to life as adults, bestowing upon them special powers.<ref> Mauro Campagnoli, [http://www.pygmies.info/baka/initiation.html Baka Pygmies—Rite of Initiation to the Spirit of the Forest.] Retrieved August 4, 2018. </ref> | |

| − | + | ====Religion==== | |

| + | Baka [[religion]] is [[animism|animist]]. They revere a supreme god called ''Komba,'' who they believe to be the creator of all things. However, this supreme god does not play much of a part in daily life, and the Baka do not actively pray to or worship ''Komba.'' ''Jengi,'' the spirit of the forest, has a much more direct role in Baka life and ritual. The Baka view ''Jengi'' as a parental figure and guardian, who presides over the male rite of [[initiation]]. ''Jengi'' is considered an integral part of Baka life, and his role as protector reaffirms the structure of Baka society, where the forest protects the men and the men in turn protect the women. | ||

| − | The | + | ===The Mbuti=== |

| + | The '''Mbuti''' inhabit the [[Congo]] region of [[Africa]], mainly in the Ituri forest in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and live in bands that are relatively small in size, ranging from 15 to 60 people. The Mbuti population is estimated to be about 30,000 to 40,000 people, though it is difficult to accurately assess a [[nomad]]ic population. There are three distinct [[culture]]s, each with their own [[dialect]], within the Mbuti; the Efe, the Sua, and the Aka. | ||

| − | + | ====Environment==== | |

| + | The forest of Ituri is a tropical [[rain forest]], encompassing approximately 27,000 square miles. In this area, there is a high amount of rainfall annually, ranging from 50 to 70 inches. The dry season is relatively short, ranging from one to two months in duration. The forest is a moist, humid region strewn with rivers and lakes.<ref> Christopher Ehret, ''The Civilizations of Africa.'' (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 2002). </ref> [[Disease]]s such as [[sleeping sickness]], are prevalent in the forests and can spread quickly, not only killing humans, but animal and plant food sources as well. Too much rainfall or [[drought]] can also affect the food supply. | ||

| + | ====Lifestyle==== | ||

| + | The Mbuti live much as their ancestors must have lived, leading a very traditional way of life in the forest. They live in territorially defined bands, and construct villages of small, circular, temporary huts, built from poles, rope made of vines, and covered with large leaves. Each hut houses a [[family]] unit. At the start of the dry season, they begin to move through a series of camps, utilizing more land area for maximum foraging. | ||

| + | The Mbuti have a vast knowledge about the forest and the foods it yields. They hunt small [[antelope]] and other game with large nets, traps, and bows.<ref name=mukenge>Tshilemalea Mukenge, ''Culture and Customs of the Congo.'' (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2002). </ref> Net hunting is done primarily during the dry season, as the nets are weakened and ineffectual when wet. | ||

| + | ====Social Structure==== | ||

| + | There is no ruling group or [[lineage]] within the Mbuti, and no overlying political organization. The Mbuti are an egalitarian society where men and women basically have equal power. Issues in the community are solved and decisions are made by consensus, and men and women engage in the conversations equally. Little political or [[social structure]] exists among the Mbuti. | ||

| + | Whereas hunting with bow and arrow is predominately a male activity, hunting with nets is usually done in groups, with men, women, and children all aiding in the process. In some instances, women may hunt using a net more often than men. The women and the children try to herd the animals to the net, while the men guard the net. Everyone engages in foraging, and both women and men take care of the children. Women are in charge of cooking, cleaning, repairing the hut, and obtaining water. | ||

| + | The cooperative relationship between the sexes is illustrated by the following description of a Mbuti playful "ritual:" | ||

| + | <blockquote>The tug-of-war begins with all the men on one side and the women on the other. If the women begin to win, one of them leaves to help out the men and assumes a deep male voice to make fun of manhood. As the men begin to win, one of them joins the women and mocks them in high-pitched tones. The battle continues in this way until all the participants have switched sides and have had an opportunity to both help and ridicule the opposition. Then both sides collapse, laughing over the point that neither side gains in beating the other.<ref> Everyculture.com, [http://www.everyculture.com/wc/Brazil-to-Congo-Republic-of/Efe-and-Mbuti.html Efe and Mbuti.] Retrieved August 4, 2018.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | = | + | Sister exchange is the common form of [[exchange marriage|marriage]] among the Mbuti. Based on reciprocal exchange, men from other bands exchange their sister or another female that they have ties to, often another relative.<ref name=mukenge/> In Mbuti society, [[bride wealth]] is not customary, and there is no formal marriage ceremony. [[Polygamy]] does occur, but is uncommon. |

| − | + | The Mbuti have a fairly extensive relationship with their Bantu villager neighbors. Never completely out of touch with the villagers, the Mbuti trade forest items such as meat, [[honey]], and animal hides for agricultural products and tools. They also turn to the village tribunal in cases of violent [[crime]]. In exchange, the villagers turn to the Mbuti for their spiritual connection to the land and forest. Mbuti take part in major ceremonies and festivals, particularly those that have to do with harvests or the fertility of the land.<ref> John Hart and Terese Hart, [https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/mbuti-zaire The Mbuti of Zaire.] ''Cultural Survival'', September 1984. Retrieved August 4, 2018. </ref> | |

| + | ====Religion==== | ||

| + | Everything in the Mbuti life is centered on the forest; they consider themselves "children of the forest," and consider the forest to be a sacred place. An important part of Mbuti spiritual life is the ''molimo.'' The ''molimo'' is, in its most physical form, a [[musical instrument]] most often made from wood, (although, in ''The Forest People,'' [[Colin Turnbull]] described his disappointment that such a sacred instrument could also easily be made of old drainpipe). | ||

| + | To the Mbuti, the ''molimo'' is also the "Song of the Forest," a festival, and a live thing when it is making sound. When not in use, the ''molimo'' is kept in a tree, and given food, water, and warmth. The Mbuti believe that the balance of "silence" (meaning peacefulness, not the absence of sound) and "noise" (quarreling and disharmony) is important; when the "noise" becomes out of balance, the youth of the tribe bring out the ''molimo.'' The ''molimo'' is also called upon whenever bad things happen to the tribe, in order to negotiate between the forest and the people.<ref name=Mark> Joan T. Mark, ''The King of the World in the Land of the Pygmies'' (University of Nebraska Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0803282506). </ref> | ||

| + | This sense of balance is evident in the song that the Mbuti sing over their dead: | ||

| + | <blockquote>There is darkness upon us; | ||

| + | <br/>Darkness is all around, | ||

| + | <br/>There is no light. | ||

| + | <br/>But it is the darkness of the forest, | ||

| + | <br/>So if it really must be, | ||

| + | <br/>Even the darkness is good.<ref name=Mark/></blockquote> | ||

| + | ==Negrito== | ||

| + | {{readout||right|250px|The Spanish term "Negrito" (little black) refers to pygmy populations in [[Asia]]}} | ||

| + | First used by early [[Spain|Spanish]] explorers to the [[Philippines]], the term ''Negrito'' (meaning "little black") is used to refer to pygmy populations outside Africa: in [[Malaysia]], the Philippines, and southeast [[Asia]]. Much like the term "Pygmy," the term "Negrito" is a blanket term imposed by outsiders, unused and often unheard of by the people it denotes, who use tribal names to identify themselves. Among the Asian groups are the [[Pygmy#The Aeta of the Phillipines|Aeta]] and the [[Batak]] (in the Philippines), the [[Semang]] (on the [[Malay Peninsula]]) and the residents of the [[Pygmy#Andaman Island Negritos|Andaman Islands]]. | ||

| − | [[ | + | References to "Black Dwarfs" can be found as early as the Three Kingdoms period of [[China]] (around 250 C.E..), describing a race of short, dark-skinned people with short, curly hair. Similar groups have been mentioned in [[Japan]], [[Vietnam]], [[Cambodia]], and [[Indonesia]], making it likely that there once was a band of Negritos covering much of Asia.<ref> Runoko Rashidi, [https://atlantablackstar.com/2014/06/28/the-black-presence-in-the-philippines%E2%80%8F/ The Black Presence in The Philippines] ''Atlanta Black Star'', June 28, 2014. Retrieved August 4, 2018. </ref> |

| − | [[ | ||

| + | ===The Aeta of the Philippines=== | ||

| + | The Aeta, (also known as Ati, Agta, or Ita) are the indigenous people of the [[Philippines]], who theoretically migrated to the islands over land bridges approximately thirty thousand years ago. Adept at living in the rainforest, many groups of Aeta believe in a Supreme Being, as well as environmental spirits that inhabit the rivers, sky, mountains, and so forth. | ||

| − | + | They perform [[ritual]] [[dance]]s, many connected with the hunt, otherwise there are no set occasions for prayer or ritual activities. They are excellent [[weaving|weavers]], producing beautiful baskets, rattan hammocks, and other containers. The Aeta practice scarification, the act of decorating one’s body with scars as well as rattan necklaces and neckbands.<ref>Camperspoint Philippines, [https://www.africanamerica.org/topic/the-aeta-people-indigenous-tribe-of-the-philippines The Aeta People: Indigenous Tribe of the Philippines] November 15, 2012. Retrieved August 4, 2018. </ref> | |

| − | The | + | ===Andaman Island Negritos=== |

| + | The [[Andaman Islands]], off the coast of [[India]], are home to several tribes of Negritos, including the Great Andamanese, the Onge, the Jarawa, and the Sentineli. The Great Andamanese first came into contact with outsiders in 1858 when [[Great Britain]] established a [[penal colony]] on the islands. Since then, their numbers have decreased from 3,500 to little more than 30, all of whom live on a reservation on a small island. | ||

| − | The [[ | + | The Onge live further inland, and were mostly left alone until Indian independence in 1947. Since 1850, their numbers have also decreased, though less drastically then the Great Andamanese, from 150 to 100. [[Alcoholism|Alcohol]] and [[drug abuse|drug]]s supplied by Indian "welfare" staff have become a problem amongst the Onge. |

| − | + | In the interior and west coasts of southern Great Andaman, the Jarawa live a reclusive life apart from Indian settlers. After a Jarawa boy was found and hospitalized in 1996 with a broken leg, contact between the "hostile" Jarawa and the Indians increased, but tensions grew, and in 2004, the Jarawa realized that they were better off without "civilized society," and once again withdrew from most contact with the outside world. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | The Sentineli live on North Sentinel Island, and are one of the world's most isolated and least-known people. Their numbers are said to be about one hundred, but this is little more than a guess, as no one has been able to approach the Sentineli. After the 2004 [[tsunami]], helicopters sent to check on the Sentineli and drop food packets were met with stone throwing and arrows.<ref> Subir Bhaumik, [http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/4181855.stm Tsunami folklore 'saved islanders'] ''BBC News'', January 20, 2005. Retrieved August 4, 2018. </ref> | ||

| + | Despite living on a group of islands, the Andamanese pygmies remain people of the forest. Groups that live along the shore never developed any strong connection with the sea, and never dare to take their outrigger canoes out of sight of land. Despite the abundance of seafood, it contributes surprisingly little to their diets, which focus mainly on pork.<ref> [https://theuniverseandman.wordpress.com/2012/09/10/the-little-people-of-the-andaman-islands/ The Little People of the Andaman Islands] September 10, 2012. Retrieved August 4, 2018. </ref> Although rumors have circulated about [[cannibalism|cannibalistic]] practices of the Andamanese, these have no basis in fact. | ||

| + | ==The Future of the Pygmies== | ||

| + | In [[Africa]], the Pygmies are in very real danger of losing their forest home, and consequently their cultural identity, as the forest is systematically cleared by logging companies. In some situations, like that in the Democratic Republic of [[Congo]], there exists a sad irony: civil war and uprisings that create a dangerous environment for the Pygmies and their neighbors are in fact responsible for keeping the logging companies at bay. Whenever a more peaceful situation is created, the logging companies judge the area safe to enter and destroy the forest, forcing resident Pygmies to leave their home and that which gives them their sense of cultural and spiritual identity. | ||

| + | In addition to the persistent loss of the rain forest, African Pygmy populations must deal with exploitation by neighboring Bantu, who often consider them equal to [[monkey]]s, and pay them for their [[labor]] in [[alcohol]] and [[tobacco]]. Many Bantu view the Pygmies as having supernatural abilities, and there is a common belief that sexual intercourse with a Pygmy can prevent or cure [[disease]]s such as [[AIDS]]; a belief that is causing AIDS to be on the rise among Pygmy populations. Perhaps most disturbing of all are the stories of [[cannibalism]] from the Congo; soldiers eating Pygmies in order to absorb their forest powers. Although this is an extreme example, it graphically illustrates the attitude that Pygmies are often considered subhuman, making it difficult for them to defend their [[culture]] against obliteration. | ||

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

| − | == | + | ==References== |

| − | *Fanso, V.G. | + | *Cline, Eric H., and Jill Rubalcaba. ''The Ancient Egyptian World''. Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0195222449 |

| − | *Neba, Aaron | + | *Ehret, Christopher. ''The Civilizations of Africa''. Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 2002. ISBN 081392085X |

| + | *Fanso, V.G. ''Cameroon History for Secondary Schools and Colleges, Vol. 1: From Prehistoric Times to the Nineteenth Century.'' Hong Kong: Macmillan Education Ltd, 1989. ISBN 0333487567 | ||

| + | *Jackson, Dorothy. [https://wrm.org.uy/articles-from-the-wrm-bulletin/section2/central-africa-nowhere-to-go-land-loss-and-cultural-degradation-the-twa-of-the-great-lakes/ Central Africa: Nowhere to go; land loss and cultural degradation. The Twa of the Great Lakes]. WRM's ''Bulletin'' Nº 87, October 2004. Retrieved February 23, 2019. | ||

| + | *Mark, Joan T. ''The King of the World in the Land of the Pygmies''. University of Nebraska Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0803282506 | ||

| + | *Mukenge, Tshilemalea. ''Culture and Customs of the Congo''. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2002. ISBN 0313314853 | ||

| + | *Neba, Aaron. ''Modern Geography of the Republic of Cameroon.'' 2nd ed. Bamenda: Neba Publishers, 1987. ISBN 0941815005 | ||

| + | *Samani, Vishva. [http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-11601101 Uganda's first Batwa pygmy graduate]. BBC News, Uganda, October 29, 2010. Retrieved February 23, 2019. | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| + | All links retrieved December 6, 2022. | ||

| + | *[http://www.pygmies.org/ African Pygmies] - Mauro Campagnoli | ||

| + | *[http://www.survivalinternational.org/tribes/pygmies The Pygmies] - Survival International | ||

| − | + | {{Credits|Pygmy|62190861|Baka_(Cameroon_and_Gabon)|55304552|Mbuti|53104648|Negrito|61451737|}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{ | ||

Latest revision as of 20:58, 14 April 2023

In anthropology, a Pygmy is a member of a hunter-gatherer people characterized by short stature. They are found in central Africa as well as parts of southeast Asia. Pygmy tribes maintain their own culture according to their own beliefs, traditions, and languages, despite interaction with neighboring tribes and various colonists.

The greatest threats to Pygmy survival in Africa comes from threatened loss of habitat due to extensive logging of the rainforests, and spread of diseases such as AIDS from neighboring tribes who regard them as subhuman.

Definition

Generally speaking, pygmy can refer to any human or animal of unusually small size (e.g. pygmy hippopotamus). In an anthropological context, however, a Pygmy is specifically a member of one of the hunter-gatherer people living in equatorial rainforests, characterized by their short height (less than 4.5 feet, on average). Pygmies are found throughout central Africa, with smaller numbers in south-east Asia, New Guinea, and the Philippines. Members of so-called Pygmy groups often consider the term derogatory, instead preferring to be called by the name of their ethnic group (for example, Baka or Mbuti). The terms "forest foragers," "forest dwellers," and "forest people" have also been used, but, for lack of an alternative, "Pygmy" remains the predominant term used throughout scientific circles.

Pygmies are smaller because in early adolescence they do not experience the growth spurt normal in most other humans. Endocrinologists consider low levels of growth hormone binding proteins to be at least partially responsible for the Pygmies' short stature.[1]

Pygmy References in History

The Pygmies are thought to be the first inhabitants of the African continent. The earliest reference to Pygmies is inscribed on the tomb of Harkuf, an explorer for the young King Pepi II of Ancient Egypt. The text is from a letter sent from Pepi to Harkuf around 2250 B.C.E., which described the boy-king's delight at hearing that Harkuf would be bringing back a pygmy from his expedition, urging him to take particular care, exclaiming, "My Majesty longs to see this pygmy more than all the treasure of Sinai and Punt!"[2] References are also made to a pygmy brought to Egypt during the reign of King Isesi, approximately 200 years earlier.

Later, more mythological references to Pygmies are found in the Greek literature of Homer, Herodotus, and Aristotle. Homer described them as:

Three-Span (Trispithami) Pygmae who do not exceed three spans, that is, twenty-seven inches, in height; the climate is healthy and always spring-like, as it is protected on the north by a range of mountains; this tribe Homer has also recorded as being beset by cranes. It is reported that in springtime their entire band, mounted on the backs of rams and she-goats and armed with arrows, goes in a body down to the sea and eats the cranes' eggs and chickens, and that this outing occupies three months; and that otherwise they could not protect themselves against the flocks of cranes would grow up; and that their houses are made of mud and feathers and egg-shells (Pliny Natural History 7.23-29).

Aristotle also wrote of Pygmies, stating that they came from the "marshlands south of Egypt where the Nile has its source." He went on to state that the existence of the Pygmies is not fiction, "but there is in reality a race of dwarfish men, and the horses are little in proportion, and the men live in caves underground."

In 1904, Samual Verner, an American explorer, was hired by the St. Louis World's Fair to bring back African pygmies for exhibition. Afterwards, he took the Africans back to their country. One Pygmy, named Ota Benga, returned to find that his entire tribe had been wiped out during his absence, and asked Verner to take him back to the United States. In September of 1906, he became part of a new exhibit at the Bronx Zoo, and was displayed in a cage in the Monkey House. The exhibit attracted up to forty thousand visitors a day, and sparked a vehement protest from African American ministers. Attempts to help Ota Benga live a normal life failed in March of 1916, when the African borrowed a gun from his host family, went into the woods, and shot himself.[3]

African Pygmies

There are many African Pygmy tribes throughout central Africa, including the Mbuti, Aka, BaBenzelé, Baka, Efé, Twa (also known as Batwa), and Wochua. Most Pygmies are nomadic, and obtain their food through a mix of foraging, hunting, fishing, and trading with inhabitants of neighboring villages. Their cultural identity is very closely tied to the rainforest, as are their spiritual and religious views. Music, as well as dance, is an important aspect of Pygmy life, and features various instruments and intricate vocal polyphony.

Pygmies are often romantically portrayed as both utopian and "pre-modern," which overlooks the fact that they have long had relationships with more "modern" non-Pygmy groups (such as inhabitants of nearby villages, agricultural employers, logging companies, evangelical missionaries, and commercial hunters.) It is often said that Pygmies have no language of their own, speaking only the language of neighboring villagers, but this is not true. Both the Baka and Bayaka (also known as the Aka), for example, have their own unique language distinct from that of neighboring villagers; the Bayaka speak Aka amongst themselves, but many also speak the Bantu language of the villagers.[4] Two of the more studied tribes are the Baka and the Mbuti, who were the subject of the well known book The Forest People (1962) by Colin Turnbull.

The Baka

The Baka Pygmies inhabit the rain forests of Cameroon, Congo, and Gabon. Because of the difficulty in determining an accurate number, population estimates range from 5,000 to 28,000 individuals. Like other Pygmy groups, they have developed a remarkable ability to use all that the forest has to offer.

They live in relative symbiosis with neighboring Bantu farmers, trading goods and services for that which cannot be obtained from the forest. The Baka speak their own language, also called Baka, as well as the language of neighboring Bantu. Most adult men also speak French and Lingala, the main lingua franca of central Africa.[5]

Lifestyle

The Baka traditionally live in single family huts called mongulu, made of branches and leaves and built predominantly by women, although more and more rectangular homes, like those of their Bantu neighbors, are being built. Hunting is one of the most important activities in Baka culture; not only for the food it provides (as many Baka live mainly by fishing and gathering), but also because of the prestige and symbolic meaning attached to the hunt. The Baka use bows, poisoned arrows, and traps to hunt game, and are well versed in the use of plants for medicine as well as poison.

Like most Pygmy groups, they move to follow the available food supply. When not camped in their permanent camp, the Baka rarely stay in one spot for longer than one week. During the rainy season, the Baka go on long expeditions into the forest to search for the wild mango, or peke, in order to produce a valued and delicious oil paste.[6]

Social Structure and Daily Life

In Baka society, men and women have fairly defined roles. Women build the huts, or mongulus, and dam small streams to catch fish. When the Baka roam the forest, women carry their few possessions and follow their husbands. Baka men have the more prestigious (and hazardous) task of hunting and trapping.

The Baka have no specific marriage ceremonies. The man builds a mud house for himself and his future wife and then brings gifts to his intended's parents. After that they live together but are not considered a permanent couple until they have children. Unlike nearby Bantu, the Baka are not polygamists.[7]

Music plays an integral role in Baka society. As with other Pygmy groups, Baka music is characterized by complex vocal polyphony, and, along with dance, is an important part of healing rituals, initiation rituals, group games and tales, and pure entertainment. In addition to traditional instruments like the flute, floor standing bow, and musical bow (which is played exclusively by women), the Baka also use instruments obtained from the Bantu, such as cylindrical drums and the harp-zither.[8] As a result of the influence of visiting European musicians, some Baka have formed a band and released an album of music, helping to spread cultural awareness and protect the forest and the Baka culture.[9]

The rite of initiation into manhood is one of the most sacred parts of a male Baka's life, the details of which are kept a closely guarded secret from both outsiders and Baka women and children. Italian ethnologist Mauro Campagnoli had the rare opportunity to take part in a Baka initiation, and is one of the only white men to officially become a part of a Baka tribe. The initiation takes place in a special hut deep in the forest, where they eat and sleep very little while undergoing a week long series of rituals, including public dances and processions as well as more secret and dangerous rites. The initiation culminates in a rite where the boys come face to face with the Spirit of the Forest, who "kills" them and then brings them back to life as adults, bestowing upon them special powers.[10]

Religion

Baka religion is animist. They revere a supreme god called Komba, who they believe to be the creator of all things. However, this supreme god does not play much of a part in daily life, and the Baka do not actively pray to or worship Komba. Jengi, the spirit of the forest, has a much more direct role in Baka life and ritual. The Baka view Jengi as a parental figure and guardian, who presides over the male rite of initiation. Jengi is considered an integral part of Baka life, and his role as protector reaffirms the structure of Baka society, where the forest protects the men and the men in turn protect the women.

The Mbuti

The Mbuti inhabit the Congo region of Africa, mainly in the Ituri forest in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and live in bands that are relatively small in size, ranging from 15 to 60 people. The Mbuti population is estimated to be about 30,000 to 40,000 people, though it is difficult to accurately assess a nomadic population. There are three distinct cultures, each with their own dialect, within the Mbuti; the Efe, the Sua, and the Aka.

Environment

The forest of Ituri is a tropical rain forest, encompassing approximately 27,000 square miles. In this area, there is a high amount of rainfall annually, ranging from 50 to 70 inches. The dry season is relatively short, ranging from one to two months in duration. The forest is a moist, humid region strewn with rivers and lakes.[11] Diseases such as sleeping sickness, are prevalent in the forests and can spread quickly, not only killing humans, but animal and plant food sources as well. Too much rainfall or drought can also affect the food supply.

Lifestyle

The Mbuti live much as their ancestors must have lived, leading a very traditional way of life in the forest. They live in territorially defined bands, and construct villages of small, circular, temporary huts, built from poles, rope made of vines, and covered with large leaves. Each hut houses a family unit. At the start of the dry season, they begin to move through a series of camps, utilizing more land area for maximum foraging.

The Mbuti have a vast knowledge about the forest and the foods it yields. They hunt small antelope and other game with large nets, traps, and bows.[12] Net hunting is done primarily during the dry season, as the nets are weakened and ineffectual when wet.

Social Structure

There is no ruling group or lineage within the Mbuti, and no overlying political organization. The Mbuti are an egalitarian society where men and women basically have equal power. Issues in the community are solved and decisions are made by consensus, and men and women engage in the conversations equally. Little political or social structure exists among the Mbuti.

Whereas hunting with bow and arrow is predominately a male activity, hunting with nets is usually done in groups, with men, women, and children all aiding in the process. In some instances, women may hunt using a net more often than men. The women and the children try to herd the animals to the net, while the men guard the net. Everyone engages in foraging, and both women and men take care of the children. Women are in charge of cooking, cleaning, repairing the hut, and obtaining water.

The cooperative relationship between the sexes is illustrated by the following description of a Mbuti playful "ritual:"

The tug-of-war begins with all the men on one side and the women on the other. If the women begin to win, one of them leaves to help out the men and assumes a deep male voice to make fun of manhood. As the men begin to win, one of them joins the women and mocks them in high-pitched tones. The battle continues in this way until all the participants have switched sides and have had an opportunity to both help and ridicule the opposition. Then both sides collapse, laughing over the point that neither side gains in beating the other.[13]

Sister exchange is the common form of marriage among the Mbuti. Based on reciprocal exchange, men from other bands exchange their sister or another female that they have ties to, often another relative.[12] In Mbuti society, bride wealth is not customary, and there is no formal marriage ceremony. Polygamy does occur, but is uncommon.

The Mbuti have a fairly extensive relationship with their Bantu villager neighbors. Never completely out of touch with the villagers, the Mbuti trade forest items such as meat, honey, and animal hides for agricultural products and tools. They also turn to the village tribunal in cases of violent crime. In exchange, the villagers turn to the Mbuti for their spiritual connection to the land and forest. Mbuti take part in major ceremonies and festivals, particularly those that have to do with harvests or the fertility of the land.[14]

Religion

Everything in the Mbuti life is centered on the forest; they consider themselves "children of the forest," and consider the forest to be a sacred place. An important part of Mbuti spiritual life is the molimo. The molimo is, in its most physical form, a musical instrument most often made from wood, (although, in The Forest People, Colin Turnbull described his disappointment that such a sacred instrument could also easily be made of old drainpipe).

To the Mbuti, the molimo is also the "Song of the Forest," a festival, and a live thing when it is making sound. When not in use, the molimo is kept in a tree, and given food, water, and warmth. The Mbuti believe that the balance of "silence" (meaning peacefulness, not the absence of sound) and "noise" (quarreling and disharmony) is important; when the "noise" becomes out of balance, the youth of the tribe bring out the molimo. The molimo is also called upon whenever bad things happen to the tribe, in order to negotiate between the forest and the people.[15]

This sense of balance is evident in the song that the Mbuti sing over their dead:

There is darkness upon us;

Darkness is all around,

There is no light.

But it is the darkness of the forest,

So if it really must be,

Even the darkness is good.[15]

Negrito

First used by early Spanish explorers to the Philippines, the term Negrito (meaning "little black") is used to refer to pygmy populations outside Africa: in Malaysia, the Philippines, and southeast Asia. Much like the term "Pygmy," the term "Negrito" is a blanket term imposed by outsiders, unused and often unheard of by the people it denotes, who use tribal names to identify themselves. Among the Asian groups are the Aeta and the Batak (in the Philippines), the Semang (on the Malay Peninsula) and the residents of the Andaman Islands.

References to "Black Dwarfs" can be found as early as the Three Kingdoms period of China (around 250 C.E.), describing a race of short, dark-skinned people with short, curly hair. Similar groups have been mentioned in Japan, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Indonesia, making it likely that there once was a band of Negritos covering much of Asia.[16]

The Aeta of the Philippines

The Aeta, (also known as Ati, Agta, or Ita) are the indigenous people of the Philippines, who theoretically migrated to the islands over land bridges approximately thirty thousand years ago. Adept at living in the rainforest, many groups of Aeta believe in a Supreme Being, as well as environmental spirits that inhabit the rivers, sky, mountains, and so forth.

They perform ritual dances, many connected with the hunt, otherwise there are no set occasions for prayer or ritual activities. They are excellent weavers, producing beautiful baskets, rattan hammocks, and other containers. The Aeta practice scarification, the act of decorating one’s body with scars as well as rattan necklaces and neckbands.[17]

Andaman Island Negritos

The Andaman Islands, off the coast of India, are home to several tribes of Negritos, including the Great Andamanese, the Onge, the Jarawa, and the Sentineli. The Great Andamanese first came into contact with outsiders in 1858 when Great Britain established a penal colony on the islands. Since then, their numbers have decreased from 3,500 to little more than 30, all of whom live on a reservation on a small island.

The Onge live further inland, and were mostly left alone until Indian independence in 1947. Since 1850, their numbers have also decreased, though less drastically then the Great Andamanese, from 150 to 100. Alcohol and drugs supplied by Indian "welfare" staff have become a problem amongst the Onge.

In the interior and west coasts of southern Great Andaman, the Jarawa live a reclusive life apart from Indian settlers. After a Jarawa boy was found and hospitalized in 1996 with a broken leg, contact between the "hostile" Jarawa and the Indians increased, but tensions grew, and in 2004, the Jarawa realized that they were better off without "civilized society," and once again withdrew from most contact with the outside world.

The Sentineli live on North Sentinel Island, and are one of the world's most isolated and least-known people. Their numbers are said to be about one hundred, but this is little more than a guess, as no one has been able to approach the Sentineli. After the 2004 tsunami, helicopters sent to check on the Sentineli and drop food packets were met with stone throwing and arrows.[18]

Despite living on a group of islands, the Andamanese pygmies remain people of the forest. Groups that live along the shore never developed any strong connection with the sea, and never dare to take their outrigger canoes out of sight of land. Despite the abundance of seafood, it contributes surprisingly little to their diets, which focus mainly on pork.[19] Although rumors have circulated about cannibalistic practices of the Andamanese, these have no basis in fact.

The Future of the Pygmies

In Africa, the Pygmies are in very real danger of losing their forest home, and consequently their cultural identity, as the forest is systematically cleared by logging companies. In some situations, like that in the Democratic Republic of Congo, there exists a sad irony: civil war and uprisings that create a dangerous environment for the Pygmies and their neighbors are in fact responsible for keeping the logging companies at bay. Whenever a more peaceful situation is created, the logging companies judge the area safe to enter and destroy the forest, forcing resident Pygmies to leave their home and that which gives them their sense of cultural and spiritual identity.

In addition to the persistent loss of the rain forest, African Pygmy populations must deal with exploitation by neighboring Bantu, who often consider them equal to monkeys, and pay them for their labor in alcohol and tobacco. Many Bantu view the Pygmies as having supernatural abilities, and there is a common belief that sexual intercourse with a Pygmy can prevent or cure diseases such as AIDS; a belief that is causing AIDS to be on the rise among Pygmy populations. Perhaps most disturbing of all are the stories of cannibalism from the Congo; soldiers eating Pygmies in order to absorb their forest powers. Although this is an extreme example, it graphically illustrates the attitude that Pygmies are often considered subhuman, making it difficult for them to defend their culture against obliteration.

Notes

- ↑ G. Baumann, M.A. Shaw, and T.J. Merimee, Low levels of high-affinity growth hormone-binding protein in African pygmies. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- ↑ Eric H. Cline and Jill Rubalcaba, The Ancient Egyptian World (Oxford University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0195222449).

- ↑ NPR, From the Belgian Congo to the Bronx Zoo. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- ↑ Daniel Duke, Aka as a Contact Language: Sociolinguistic and Grammatical Evidence.

- ↑ Daiji Kimura, Utterance Overlap and Long Silence Among the Baka Pygmies: Comparison with Bantu Farmers and Japanese University Students.

- ↑ Laurent Maget and Baptiste Bouleau, A Mango Harvest with the Baka Pygmies CNRS News, May 11, 2016. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- ↑ Baka (Pygmy) People Trip Down Memory Lane, August 15, 2013. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- ↑ Mauro Campagnoli, Baka Pygmies—Music and Musical Instruments. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- ↑ BBC, Who are the Baka Pygmies? And What are They Doing in Gateshead? Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- ↑ Mauro Campagnoli, Baka Pygmies—Rite of Initiation to the Spirit of the Forest. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- ↑ Christopher Ehret, The Civilizations of Africa. (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 2002).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Tshilemalea Mukenge, Culture and Customs of the Congo. (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2002).

- ↑ Everyculture.com, Efe and Mbuti. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- ↑ John Hart and Terese Hart, The Mbuti of Zaire. Cultural Survival, September 1984. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Joan T. Mark, The King of the World in the Land of the Pygmies (University of Nebraska Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0803282506).

- ↑ Runoko Rashidi, The Black Presence in The Philippines Atlanta Black Star, June 28, 2014. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- ↑ Camperspoint Philippines, The Aeta People: Indigenous Tribe of the Philippines November 15, 2012. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- ↑ Subir Bhaumik, Tsunami folklore 'saved islanders' BBC News, January 20, 2005. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- ↑ The Little People of the Andaman Islands September 10, 2012. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cline, Eric H., and Jill Rubalcaba. The Ancient Egyptian World. Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0195222449

- Ehret, Christopher. The Civilizations of Africa. Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 2002. ISBN 081392085X

- Fanso, V.G. Cameroon History for Secondary Schools and Colleges, Vol. 1: From Prehistoric Times to the Nineteenth Century. Hong Kong: Macmillan Education Ltd, 1989. ISBN 0333487567

- Jackson, Dorothy. Central Africa: Nowhere to go; land loss and cultural degradation. The Twa of the Great Lakes. WRM's Bulletin Nº 87, October 2004. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- Mark, Joan T. The King of the World in the Land of the Pygmies. University of Nebraska Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0803282506

- Mukenge, Tshilemalea. Culture and Customs of the Congo. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2002. ISBN 0313314853

- Neba, Aaron. Modern Geography of the Republic of Cameroon. 2nd ed. Bamenda: Neba Publishers, 1987. ISBN 0941815005

- Samani, Vishva. Uganda's first Batwa pygmy graduate. BBC News, Uganda, October 29, 2010. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

External links

All links retrieved December 6, 2022.

- African Pygmies - Mauro Campagnoli

- The Pygmies - Survival International

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.