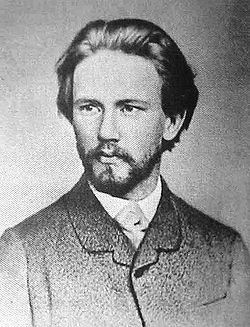

Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Pyotr (Peter) Ilyich Tchaikovsky (Russian: Пётр Ильич Чайкoвский, Pjotr Il’ič Čajkovskij; listen ▶ (7 May [O.S. 25 April] 1840 – 6 November [O.S. 25 October] 1893), also transliterated Piotr Ilitsch Tschaikowski, Petr Ilich Tschaikowsky, Piotr Illyich Tchaikovsky, as well as many other versions, was a Russian composer of the Romantic era. Although not a member of the group of nationalistic composers usually known in English-speaking countries as 'The Five', his music has come to be known and loved for its distinctly Russian character as well as for its rich harmonies and stirring melodies. His works, however, were much more western than those of his Russian contemporaries as he effectively used international elements in addition to national folk melodies.

Early life

Pyotr Tchaikovsky was born on April 25, 1840 (Julian calendar) or May 7 (Gregorian calendar) in Votkinsk, a small town in present-day Udmurtia (at the time the Vyatka Guberniya under Imperial Russia), the son of a mining engineer in the government mines and the second of his three wives, Alexandra, a Russian woman of French ancestry. He was the older brother (by some ten years) of the dramatist, librettist, and translator Modest Ilyich Tchaikovsky. Musically precocious, Pyotr began piano lessons at the age of five, and in a few months he was already proficient at Friedrich Kalkbrenner's composition Le Fou. In 1850, his father was appointed director of the St Petersburg Technological Institute. There, the young Tchaikovsky obtained an excellent general education at the School of Jurisprudence, and furthered his instruction on the piano with the director of the music library. Also during this time, he made the acquaintance of the Italian master Luigi Piccioli, who influenced the young man away from German music, and encouraged the love of Rossini, Bellini, and Donizetti. His father indulged Tchaikovsky's interest in music by funding studies with Rudolph Kündinger, a well-known piano teacher from Nuremberg. Under Kündinger, Tchaikovsky's aversion to German music was overcome, and a lifelong affinity with the music of Mozart was seeded. When his mother died of cholera in 1854, the 14-year-old composed a waltz in her memory.

Tchaikovsky left school in 1858 and received employment as an under-secretary in the Ministry of Justice, where he soon joined the Ministry's choral group. In 1861, he befriended a fellow civil servant who had studied with Nikolai Zaremba, who urged him to resign his position and pursue his studies further. Not ready to give up employment, Tchaikovsky agreed to begin lessons in musical theory with Zaremba. The following year, when Zaremba joined the faculty of the new St Petersburg Conservatory, Tchaikovsky followed his teacher and enrolled, but still did not give up his post at the ministry, until his father consented to support him. From 1862 to 1865, Tchaikovsky studied harmony, counterpoint and the fugue with Zaremba, and instrumentation and composition under the director and founder of the Conservatory, Anton Rubinstein, who was both impressed by and envious of Tchaikovsky's talent.

Musical career

ewen: hies early works gave every indication of serving the cause of Russian nationalism: Little Russian, The Voyevoda, The Oprichnik, Vakula the SMith made copious and effective use of Russian folk songs and dances. the national element is still pronounced in teh first acto fo Eugene Onegin. then he began drawing away from folk sources toward a mroe cosmpolitan style, allowed himself to be influenced by German Romanticism; he sought to bring to his writing the elegance, sophistsication, and good breeding of the WEstern world. For these strong European leanings he was violently attacked by the die-hard nationalists. THey found him a negation of the principles for which they stood.

Yet it was Tchaikovsky who was the first to bring about a genuine appreciation of Russian music in the Western world and he is the one who represents Russian music. Even though he abandoned Russian nationalism, nationalism never abandoned him, as evidenced in his Russian melodies and rhythmsas well as the Russian tendency toward brooding and melancholia dominated his moods.

"As to the Russian element in my music generally, its melodic and hamronic relation to folk music—I grew up in a quiet place and was drenched from the earliest childhood with the wonderful beauty of Russian popular songs. I am, therefore, passionately devoted to every expression of the Russian spirit. In brief, I am a Russian, through and through." ewen 737

Stravinsky: "Tchaikovsky's music, which does not appear Russian to everybody, is often more profoundly Russian than music which has long since been awarded the facile label of Muscovite picturesqueness. THis music is quite as Russian as Pushkin's verse or Glinka's song. Whilst not specially cultivating in his art the 'soul of the Russian peasonat,' Tchaikovsky drew unconsciously from the true, popular sources of our race." ewen 737-738

rephrased - An interesting phenomenon occurred: Russian contemporaries attacked him for being too European, while Europeans criticized him for being too russian. His sentimentality that tends to slide towards bathos as well as his style, seen by some as superficial at times, and a pathos and pessimism that boil down to hysteria, and melancholia that evokes self-pity. (this is evident in works of other Eastern Europeans as well). Although these are credible accusations to a degree, he is the most popular Russian composer for the ability to speak from heart to heart and convey beuaty in sadness.

Richard Anthony Leonard: ...expressive and communicative in the highest degree. That is is also comparatively easy to absorb and appreciate shouodl be accounted among its virtues instead of its faults." ewen 738

After graduating, Tchaikovsky was approached by Anton Rubinstein's younger brother Nikolai Grigoryevich Rubinstein to become professor of harmony, composition, and the history of music. Tchaikovsky gladly accepted the position, as his father had retired and lost his property. The next ten years were spent teaching and composing. Teaching proved taxing, and in 1877 he suffered a breakdown. After a year off, he attempted to return to teaching, but retired his post soon after. He spent some time in Italy and Switzerland, but eventually took residence with his sister, who had an estate just outside Kiev.

Tchaikovsky took to orchestral conducting after filling in at a performance in Moscow of his opera The Enchantress (Russian: Чародейка) (1885-7). Overcoming a life-long stage fright, his confidence gradually increased to the extent that he regularly took to conducting his pieces.

Tchaikovsky visited America in 1891 in a triumphant tour to conduct performances of his works. On May 5, he conducted the New York Music Society's orchestra in a performance of Marche Solennelle on the opening night of New York's Carnegie Hall. That evening was followed by subsequent performances of his Third Suite on May 7, and the a cappella choruses Pater Noster and Legend on May 8. The US tour also included performances of his Piano Concerto No. 1 and Serenade for Strings.

Just nine days after the first performance of his Symphony No. 6, Pathétique, in 1893, in St Petersburg, Tchaikovsky died (see section below).

Some musicologists (e.g. Milton Cross, David Ewen) believe that he consciously wrote his Sixth Symphony as his own Requiem. In the development section of the first movement, the rapidly progressing evolution of the transformed first theme suddenly "shifts into neutral" in the strings, and a rather quiet, harmonized chorale emerges in the trombones. The trombone theme bears absolutely no relation to the music that preceded it, and none to the music which follows it. It appears to be a musical "non sequitur", an anomaly — but it is from the Russian Orthodox Mass for the Dead, in which it is sung to the words: "And may his soul rest with the souls of all the saints." Tchaikovsky was interred in Tikhvin Cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery in St Petersburg.

His music included some of the most renowned pieces of the romantic period. Many of his works were inspired by events in his life.

Personal life

During his education at the School of Jurisprudence, he was infatuated with a soprano, but she married another man. One of his conservatory students, Antonina Miliukova, a neurotic woman, who in fell on her knees in adoration before him during her first interview with him, began writing him passionate letters around the time that he had made up his mind to "marry whoever will have me." He did not even remember her from his classes, but her letters were very persistent, and he hastily married her on July 18, 1877. In a letter to his brother he mentioned that he did not love her but wanted to make a statement to quell the rumors that he was homosexual. Within days, while still on their honeymoon, he deeply regretted his decision. Two weeks after the wedding the composer supposedly attempted suicide by putting himself into the freezing Moscow River, and then he left Russia for a yearlong travel around Europe. He never returned to his wife after that but did send her a regular allowance through the years. Though they never again cohabitated with each other, they remained legally married until his death. Three years after his death, Antonina was consigned to a mental hospital.

The composer's homosexuality, as well as its importance to his life and music, has long been recognized, though any proof of it was suppressed during the Soviet era.[1] Although some historians continue to view him as heterosexual, many others — such as Rictor Norton and Alexander Poznansky — accept that some of Tchaikovsky's closest relationships may have been homosexual, (citing his servant Aleksei Sofronov and perhaps even his nephew, Vladimir "Bob" Davydov.) Evidence that Tchaikovsky was homosexual is drawn from his letters and diaries, as well as the letters of his brother, Modest, who was also homosexual.

A far more influential woman in Tchaikovsky's life was a wealthy widow and a musical dilettante, Nadezhda von Meck, with whom he exchanged over 1,200 letters between 1877 and 1890. At her insistence they never met; they did encounter each other on two occasions, purely by chance, but did not converse. As well as financial support in the amount of 6,000 rubles a year, she expressed interest in his musical career and admiration for his music. The relationship evolved into love, and Tchaikovsky spoke to her freely about his innermost feelings and aspirations. However, after 13 years she ended the relationship unexpectedly, claiming bankruptcy. Other sources attribute this to the social gap between them and her love of her children, which she would not jeopardize by any means. He sent an an anxious letter pleading for the continued friendship, stating that he was no longer in need of her finances, but his letter went unanswered. Then he discovered that she had not suffered any reverse in fortune. The two were related by marriage in their families— one of her sons, Nikolay, was married to Tchaikovsky's niece Anna Davydova.During this period, Tchaikovsky had already achieved success throughout Europe and by 1891, even greater accolades in the United States, where he was the conductor of his 1812 Overture at the opening night of Carnegie Hall on May 5th, 1891.

Upon return to Russia, his spleen grew to the point that he thought he was on the verge of lunacy. Tchaikovsky's life is the subject of Ken Russell's poorly researched and highly fictionalized motion picture The Music Lovers (1970). Two other motion pictures were based on his life - the low-budgeted, sanitized and also highly fictionalized Song of My Heart, released in 1948, and the 1969 Russian-language "Tchaikovsky" , which was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

His last name derives from the word chaika (чайка), meaning seagull in a number of Slavic languages. His family origins may not have been entirely Russian. In an early letter to Nadezhda von Meck, Tchaikovsky wrote that his name was Polish and his ancestors were "probably Polish." (In fact, the Polish equivalent of his name, Czajkowski, is a not uncommon Polish surname.)

Tchaikovsky's death

Until recent years it had been generally assumed that Tchaikovsky died of cholera after drinking contaminated water, particularly because he was careless enough to drink unboiled water during a cholera epidemic. However, a controversial theory published in 1980 by Aleksandra Orlova and based only on oral history (i.e., without documentary evidence), explains Tchaikovsky's death as a suicide.

In this account, Tchaikovsky committed suicide by consuming small doses of arsenic following an attempt to blackmail him over his homosexuality. His alleged death by cholera (whose symptoms have some similarity with arsenical poisoning) is supposed to have been a cover for this suicide. According to the theory, Tchaikovsky's own brother Modest Tchaikovsky, also homosexual, helped conspire to keep the secret. There are many circumstantial events that some say lend credence to the theory, such as wrong dates on the death certificate, conflicting testimony from Modest and the doctor about the timeline of his death, the fact that Tchaikovsky's funeral was open casket, and that the sheets from his deathbed were merely laundered instead of being burned. There are also passages in Rimsky-Korsakov's autobiography years later about how people at the funeral kissed Tchaikovsky on the face, even though he had died from cholera. These passages were deleted by Russian authorities from later editions of Rimsky-Korsakov's book.

The suicide theory is hotly disputed by others, including Alexander Poznansky, who argues that Tchaikovsky could easily have drunk tainted water because his class regarded cholera as a disease that afflicted only poor people, or because restaurants would mix cool boiled water with unboiled; that the circumstances of his death are entirely consistent with cholera; and that homosexuality ("gentlemanly games") was widely tolerated among the upper classes of Tsarist Russia. To this day, no one knows how Tchaikovsky truly died.

The English composer Michael Finnissy has composed a short opera, Shameful Vice, about Tchaikovsky's last days and death.

Musical works

Songs

- “Again, as Before, Alone,” op. 73, no. 6

- "Deception," op. 65, no. 2

- "Don Juan's Serenade," op. 38, no. 1

- "Gypsy's Song," op. 60, no. 7

- "I Bless You, Forests," op. 47, no. 5

- "If I had Only Known," op. 47, no. 1

- "In This Moonlight," op. 73, no. 3

- "It Was in Early Spring," op. 38, no. 2

- "A Legend" ("Christ in His Garden"), op. 54, no. 5

- "Lullaby," op. 54, no. 1

- "None But the Lonely Heart," op. 6, no. 6

- "Not a Word, O My Friend," op. 6, no. 2

- "Only Thou," op. 57, no. 6

- "Pimpinella," op. 38, no. 6

- "Tears," op. 65, no. 5

- "Was I Not a Little Blade of Grass," op. 47, no. 7

- "We Sat Together," op. 73, no. 1

- "Why?" op. 6, no. 5

Tchaikovsky was criticized by some of his fellow composers and contemporaries for his song-writing methods, such as altering text of the songs to suit his melody, for the inadequacy of his musical declamation, for carelessness, and for outdated techniques. Cesar Cui was at the helm of these criticisms, but Tchaikovsky's dismissal was very insightful: "Absolute accuracy of musical declamation is a negative quality, and its importance should not be exaggerated. What does the repetition of words, even of whole sentences, matter? There are cases where such repetitions are completely natural and in harmony with reality. Under the influence of strong emotion a person repeats one and the same exclamation and sentence very often.... But even if that never happened in real life, I should feel no embarrassment in impudently turning my back on 'real' truth in favor of 'artistic' truth. ewen 741

Edwin Evans found him straddling two cultures: Teutonic and Slavonic, as his melodies are more emotional than those found in songs that originated in Germany and they express more of the physical than the intellectual beauty. ewen 742 His strength lay in his lyricism and a plethora of styles, moods, and atmosphere.

Ballets=

Tchaikovsky is well known for his ballets, although it was only in his last years, with his last two ballets, that his contemporaries came to really appreciate his finer qualities as ballet music composer.

- (1875–1876): Swan Lake, Op. 20. Tchaikovsky's first ballet, it was first performed (with some omissions) at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow in 1877. It was not until 1895, in a revival by Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov that the ballet was presented in the definitive version it is still danced in today (the music for this revival was much revised by the composer Riccardo Drigo in a version still used by most ballet companies today).

- (1888–1889): The Sleeping Beauty, Op. 66. This work Tchaikovsky considered to be one of his best. Commissioned by the director of the Imperial Theatres, Ivan Vsevolozhsky, its first performance was in January,1890 at the Mariinsky Theatre in St Petersburg.

- (1891–1892): The Nutcracker, Op. 71. Tchaikovsky himself was less satisfied with this, his last ballet. Though he accepted the commission (again granted by Ivan Vsevolozhsky), he did not particularly want to write it (though he did write to a friend while composing the ballet: "I am daily becoming more and more attuned to my task.") This ballet premiered on a double-bill with his last opera, Iolanta (Iolanthe). Among other things, the score of Nutcracker is noted for its use of the celesta, an instrument that the composer had already employed in his much lesser known symphonic poem The Voyevoda (premiered 1891).^ Although well-known in Nutcracker as the featured solo instrument in the "Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy" from Act II, it is employed elsewhere in the same act.

- Note: This was the only ballet from which Tchaikovsky himself derived a suite (the "suites" from the other ballets were devised by other hands). The Nutcracker Suite is often mistaken by novice listeners as the ballet itself, but it consists of only eight selections from the score intended for concert performance.

Operas

Tchaikovsky completed ten operas, although one of these is mostly lost and another exists in two significantly different versions. In the West his most famous are Eugene Onegin and The Queen of Spades.

- Voyevoda (Воевода – The Voivode, Op. 3, 1867 – 1868)

- Full score destroyed by composer, but posthumously reconstructed from sketches and orchestral parts

- Undina (Ундина or Undine, 1869)

- Was not completed. Only a march sequence from this opera saw the light of day, as the second movement of his Symphony #2 in C Minor and a few other segments are occasionally heard as concert pieces. Interestingly, while Tchaikovsky revised the Second symphony twice in his lifetime, he did not alter the second movement (taken from the Undina material) during either revision. The rest of the score of Undina was destroyed by the composer.

- The Oprichnik] (Опричник), 1870–1872

- Premiere April 24 [OS April 12], 1874, St Petersburg

- Vakula the Smith (Кузнец Вакула – Kuznets Vakula), Op. 14, 1874;

- Revised later as Cherevichki, premiere December 6 [OS November 24], 1876, Saint Petersburg

- Eugene Onegin (Евгений Онегин – Yevgeny Onegin), Op. 24, 1877–1878

- Premiere March 29 [OS March 17] 1879 at the Moscow Conservatory

- The Maid of Orleans (Орлеанская дева – Orleanskaya deva), 1878–1879

- Premiere February 25 [OS February 13], 1881, Saint Petersburg

- Mazeppa (Мазепа), 1881–1883

- Premiere February 15 [OS February 3] 1884, Moscow

- Cherevichki (Черевички; revision of Vakula the Smith) 1885

- Premiere January 31 [OS January 19], 1887, Moscow

- The Enchantress (or The Sorceress, Чародейка – Charodeyka), 1885–1887

- Premiere November 1 [OS October 20] 1887, St Petersburg

- The Queen of Spades (Пиковая дама - Pikovaya dama), Op. 68, 1890

- Premiere December 19 [OS December 7] 1890, St Petersburg

- Iolanthe (Иоланта – Iolanthe), Op. 69, 1891

- First performance: Maryinsky Theatre, Saint Petersburg, 1892. Originally performed on a double-bill with The Nutcracker

(Note: A "Chorus of Insects" was composed for the projected opera Mandragora [Мандрагора] of 1870).

Symphonies

Tchaikovsky's earlier symphonies are generally optimistic works of nationalistic character, while the later symphonies are more intensely dramatic, particularly in the Sixth, a clear declaration of despair. The last three of his numbered symphonies (the fourth, fifth and sixth) are recognized as highly original examples of symphonic form and are frequently performed.

- (1866): Symphony No. 1 in G minor, Op. 13, Winter Daydreams

- (1872): Symphony No. 2 in C minor, Op. 17, Little Russian

- (1875): Symphony No. 3 in D major, Op. 29, Polish

- (1877–1878): Symphony No. 4 in F minor, Op. 36

- (1885): Manfred Symphony, B minor, Op. 58. Inspired by Byron's poem "Manfred"

- (1888): Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Op. 64

- (Symphony No. 7: see below, Piano Concerto No. 3)

- (1893): Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 74, Pathétique – considered as his best. Written under the torment of an intense depression.

He also wrote four orchestral suites in the ten years between the 4th and 5th symphonies. He originally intended to designate one or more of these as a "symphony" but was persuaded to alter the title. The four suites are nonetheless symphonic in character, and, compared to the last three symphonies, are undeservedly neglected.

Concerti

- (1874–1875): Of his three piano concerti, it is Piano Concerto No. 1 in [[B-flat minor, Op. 23, which is best known and most highly regarded, and one of the most popular piano concertos ever written. He dedicated it to the pianist Nikolai Rubinstein. When he played it for Rubinstein in an empty classroom in the Conservatory, Rubinstein was silent, and when the performance ended, Rubinstein told Tchaikovsky that his concerto was worthless and unplayable for its commonplace passages that were beyond improvement, for its triviality and vulgarity and borrowings from other composers and sources. Tchaikovsky's response was, "I shall not change a single note." Ewen 745 This It was initially rejected by its dedicatee, as poorly composed and unplayable, and subsequently premiered by Hans von Bülow (who was delighted to find such a piece to play) in Boston, Massachusetts on 25 October, 1875. Rubinstein later admitted his error of judgment, and included the work in his own repertoire.

- (1878): His Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 35, was composed in less than a month during March and April 1878, but its first performance was delayed until 1881 because Leopold Auer, the violinist to whom Tchaikovsky had intended to dedicate the work, refused to perform it: he stated that it was unplayable. Instead it was first performed by the relatively unknown Austrian violinist Adolf Brodsky, who received the work by chance. This violin concerto is one of the most popular concertos for the instrument and is frequently performed today.

- (1879): Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto No. 2, Op. 44, is an eloquent, less extroverted piece with a violin and cello added as soloists in the second movement.

- (1892): The so-called Piano Concerto No. 3 has a curious and complicated history. Commenced after the Symphony No. 5, it was intended initially to be the composer's next (i.e., sixth) symphony. However, after nearly finishing the sketches and some orchestration of the first movement, Tchaikovsky abandoned work on this score as a symphony. However, in 1893, after beginning work on what is now known as Symphony No. 6 (Pathétique), he reworked the sketches of the first movement and completed the instrumentation to create a piece for piano and orchestra known as Allegro de concert or Konzertstück (published posthumously as Op. 75). Tchaikovsky also produced a piano arrangement of the slow movement (Andante) and last movement (Finale) of the symphony. He turned the scherzo into another piano piece, the Scherzo-fantasie in E-flat minor, Op. 72, No. 10. After Tchaikovsky's death, the composer Sergei Taneyev completed and orchestrated the Andante and Finale, published as Op. 79. A reconstruction of the original symphony from the sketches and various reworkings was accomplished during 1951–1955 by the Soviet composer Semyon Bogatyrev, who brought the symphony into finished, fully orchestrated form and issued the score as Tchaikovsky's Symphony No 7 in E-flat major.[2]

Other works

For orchestra

- (1869 revised 1870, 1880): Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture]]. Written on suggestion from Balakirev. Balakirev was not satisfied with its first version and suggested numreous changes; after the revision, Balakirev declared that it was his best work. Later on Tchaikovsky revised it again, which is the version enjoyed by present audiences. This piece contains one of the world's most famous melodies. The tremendously famous love theme in the middle of this long symphonic poem has been used countless times in commercials and movies, frequently as a spoof to traditional love scenes.

- (1873): The Tempest "Symphonic Fantasia After Shakespeare, Op. 18"

- (1876): Slavonic March (Marche Slave), Op. 31. This piece is another well-known Tchaikovsky piece and is often played in conjunction with the 1812 Overture. This work uses the Tsarist National Anthem. It is mostly in a minor key and is yet another very recognizable piece, commonly referenced in cartoons, commercials and the media. The piece is much in the style of a Capriccio.

- (1876): Francesca da Rimini, Op. 32. This piece has been described as "pure melodrama" similar to stretches of Verdi operas; [1] some passages are similar to sword-fight clashes in Romeo and Juliet. When Francesca da Rimini was conducted by Leonard Bernstein in 1989, slowed from 20 minutes to 30, it was reviewed in the New York Times as a "masterpiece". [2]

- (1880): Capriccio Italien, Op. 45. This piece is a traditional caprice or capriccio in an Italian style. Tchaikovsky stayed in Italy in the late 1870s to early 1880s and throughout the various festivals he heard many themes, some of which were played by trumpets, samples of which can be heard in this caprice. It has a lighter character than many of his works, even "bouncy" in places, and is often performed today in addition to the 1812 Overture.

- The title used in English-speaking countries is a linguistic hybrid: it contains an Italian word ("Capriccio") and a French word ("Italien"). A fully Italian version would be Capriccio Italiano; a fully French version would be Caprice Italien.

- (1880): Serenade in C for String Orchestra, Op. 48. The first movement, In the form of a sonatina, was an homage to Mozart. The second movement is a Waltz, followed by an Elegy and a spirited Russian finale, Tema Russo. In his score, Tchaikovsky supposedly wrote, "The larger the string orchestra, the better will the composer's desires be fulfilled."

- (1880): 1812 Overture, Op. 49. This piece was reluctantly written by Tchaikovsky to commemorate the Russian victory over Napoleon in the Napoleonic Wars. It is known for its traditional Russian themes (such as the old Tsarist National Anthem) as well as its famously triumphant and bombastic coda at the end which uses 16 cannon shots and a chorus of church bells. Despite its popularity, Tchaikovsky wrote that he "did not have his heart in it".

- (1883): Coronation March, Op. 50. The mayor of Moscow commissioned this piece for performance in May 1883 at the coronation of Aleksandr III. Tchaikovsky's arrangement for solo piano and E. L. Langer's arrangement for piano duet were published in the same year.

For orchestra, choir and vocal soloists

- (1873) Snegurochka (The Snow Maiden) , incidental music for Alexander Ostrovsky's play of the same name. Ostrovsky adapted and dramatized a popular Russian fairy tale, (http://clover.slavic.pitt.edu/~tales/snow_maiden.html) and the score that Tchaikovsky wrote for it was always one of his own favorite works. It contains much vocal music, but it is not a cantata, nor an opera.

For orchestra, soprano, and baritone

- (1891) Hamlet , incidental music for Shakespeare's play. The score uses music borrowed from Tchaikovsky's overture of the same name, as well as from his Symphony No. 3, and from The Snow Maiden, in addition to original music that he wrote specifically for a stage production of Hamlet. The two vocal selections are a song that Ophelia sings in the throes of her madness, and a song for the First Gravedigger to sing as he goes about his work.

For choir, songs, chamber music, and for solo piano and violin

- (1871) String Quartet No. 1 in D major, Op. 11

- (1876) Variations on a Rococo theme for cello and orchestra, Op. 33.

- (1876) Piano suite The Seasons, Op. 37a

- Three pieces: Meditation, Scherzo and Melody op. 42, for violin and piano

- (1881) Russian Vesper Service, Op. 52

- (1882) Piano Trio in A minor, Op. 50

- (1886) Dumka, Russian rustic scene in C minor for piano, Op. 59

- (1890) String sextet Souvenir de Florence, Op. 70

For a complete list of works by opus number, see [3]. For more detail on dates of composition, see [4].

Media

|

See also

- Nadezhda von Meck

- Antonina Miliukova Tchaikovskaya

- Nikolai Grigoryevich Rubinstein

- Tchaikovsky International Competition

- Tchaikovsky Symphony Orchestra of Moscow Radio

- Category:Compositions by Pyotr Tchaikovsky

- Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians

Citations

- ↑ http://www.glbtq.com/arts/tchaikovsky_pi.html

- ↑ Wiley, Roland. 'Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Il′yich, §6(ii): Years of valediction, 1889–93: The last symphony'; Works: solo instrument and orchestra; Works: orchestral, Grove Music Online (Accessed 07 February 2006), <http://www.grovemusic.com> (subscription required). Brown, David. Tchaikovsky: the Final Years (1885-1893). New York: W.W. Norton, 1991, pp. 388-391, 497.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Poznansky, Alexander & Langston, Brett The Tchaikovsky Handbook: A guide to the man and his music. (Indiana University Press, 2002) Vol. 1. Thematic Catalogue of Works, Catalogue of Photographs, Autobiography. 636 pages. ISBN 0-253-33921-9. Vol. 2. Catalogue of Letters, Genealogy, Bibliography. 832 pages. ISBN 0-253-33947-2.

- Greenberg, Robert "Great Masters: Tchaikovsky — His Life and Music"

- Holden, Anthony Tchaikovsky: : A Biography Random House; 1st U.S. ed edition (February 27, 1996) ISBN 0-679-42006-1

- Kamien, Roger. Music : An Appreciation. Mcgraw-Hill College; 3rd edition (August 1, 1997) ISBN 0-07-036521-0

- ed. John Knowles Paine, Theodore Thomas, and Karl Klauser (1891). Famous Composers and Their Works, J.B. Millet Company.

- Meck Galina Von, Tchaikovsky Ilyich Piotr, Young Percy M. Tchaikovsky Cooper Square Publishers; 1st Cooper Square Press ed edition (October, 2000) ISBN 0-8154-1087-5

- Meck, Nadezhda Von Tchaikovsky Peter Ilyich, To My Best Friend: Correspondence Between Tchaikovsky and Nadezhda Von Meck 1876-1878 Oxford University Press (January 1, 1993) ISBN 0-19-816158-1

- Poznansky, Alexander, Tchaikovsky's Last Days, Oxford University Press (1996), ISBN 0-19-816596-X

- Poznansky, Alexander Tchaikovsky: the Quest for the Inner Man Lime Tree (1993) ISBN 0-413-45721-4 (hb), ISBN 0-413-45731-1 (pb)

- Poznansky, Alexander. Tchaikovsky through others' eyes. (Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press, 1999). ISBN 0-253-35545-0.

- Tchaikovsky, Modest The Life And Letters Of Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky University Press of the Pacific (2004) ISBN 1-4102-1612-8

- Tchaikovsky's sacred works by Polyansky

- Biography of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts

External links

- Tchaikovsky research (active site)

- Tchaikovsky (inactive site)

- Tchaikovsky page (inactive site)

- PBS Great Performances biography of Tchaikovsky

- Tchaikovsky cylinder recordings, from the Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara Library.

Public Domain Sheet Music:

- IMSLP - International Music Score Library Project's Tchaikovsky page.

- Mutopia Project Tchaikovsky Sheet Music at Mutopia

- WIMA Tchaikovsky Sheet Music at Werner Icking Music Archive

| Romanticism | |

|---|---|

| Eighteenth century - Nineteenth century | |

| Romantic music: Beethoven - Berlioz - Brahms - Chopin - Grieg - Liszt - Puccini - Schumann - Tchaikovsky - The Five - Verdi - Wagner | |

| Romantic poetry: Blake - Burns - Byron - Coleridge - Goethe - Hölderlin - Hugo - Keats - Lamartine - Leopardi - Lermontov - Mickiewicz - Nerval - Novalis - Pushkin - Shelley - Słowacki - Wordsworth | |

| Visual art and architecture: Brullov - Constable - Corot - Delacroix - Friedrich - Géricault - Gothic Revival architecture - Goya - Hudson River school - Leutze - Nazarene movement - Palmer - Turner | |

| Romantic culture: Bohemianism - Romantic nationalism | |

| << Age of Enlightenment | Victorianism >> Realism >> |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.