William Blake

William Blake (November 28, 1757 â August 12, 1827) was an English poet, painter and printmaker. Largely unrecognized during his lifetime, Blake is regarded today as an major, if iconoclastic figure, a religious visionary whose art and poetry prefigured, and came to influence, the Romantic movement.

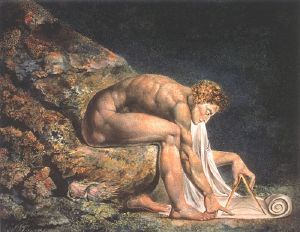

Blake valued imagination above reason, but unlike later Romantics, he deferred to inner visions and spiritual perception as surer denoters of the truth than sentiment or emotional response to nature. "If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, infinite," Blake wrote in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. "For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things throâ narrow chinks of his cavern."

Blake's explorations of good and evil, heaven and hell, knowledge and innocence, and outer versus inner reality were unorthodox and perplexing to eighteen-century sensibilities. His well-known works, Songs of Innocence (1789) and Songs of Experience (1794), contrast benign perceptions of life from the perspective of innocent children with a mature person's experience of pain, ignorance, and vulnerability. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who received a copy of Songs of Innocence and Experience, considered Blake a "man of Genius."

Blake admired and studied the Renaissance masters, and he experimented by combining his own poetry and engravings on the same plate to produce a composite artistic statement. His illustrations often included fantastic, metaphorical creatures drawn from Greek and Roman mythology, with characters representing inspiration and creativity battling against arbitrary and unjust forces like law and religion.

Blake's antagonism toward established religion, the authority of government, and social and sexual conventions have influenced liberal thought and attitudes to the present day. His openness to spiritual inspiration largely bypassed Romantic emotional preoccupations and can be seen as an early influence on the modern New Age movement. Though Blake lived in poverty and died largely unrecognized, his works present a unique and significant contribution to European art and literature.

Early life

Childhood and family

Blake was born at 28a Broad Street, Golden Square, London into a middle-class family. He was one of four children (an older brother died in infancy). His father was a hosier. The Blakes are believed to have belonged to a radical religious sect called Dissenters; however, the exact identity of the sect is a mystery. The Bible was an early and profound influence on Blake, and would remain a crucial source of inspiration throughout his life.

From a young age, Blake is said to have had visions. The earliest certain instance was when, at the age of about eight or ten in Peckham Rye, London, he saw a tree filled with angels "bespangling every bough like stars." According to his Victorian biographer Gilchrist, Blake returned home and reported this vision, only escaping a thrashing from his father by the intervention of his mother. Though all the evidence suggests that Blake's parents were supportive and of a broadly liberal bent, his mother seems to have been especially supportive; several of Blake's early drawings and poems decorated the walls of her chamber.

On another occasion, Blake beheld haymakers at work, and saw angelic figures walking among them. It is possible that other visions occurred before these incidents. Later in his life, Blake's wife Catherine would recall to him the time he beheld God's head "put to the window."

Blake began engraving copies of drawings of Greek antiquities purchased for him by his father (a further indication of the support Blake's parents lent their son), a practice that was then preferred to real-life drawing. Within these drawings Blake found his first exposure to classical forms through the work of Raphael, Michelangelo, Martin Hemskerck and Albert DĂŒrer (Blake Record, 422). His parents knew enough of his headstrong temperament that he was not sent to school but was instead enrolled in drawing classes. He read avidly on subjects of his own choosing. During this period, Blake was also making explorations into poetry; his early work displays knowledge of Ben Johnson and Edmund Spenser.

Apprenticeship to Basire

On August 4, 1772, Blake became apprenticed to an engraver, James Basire of Great Queen Street, for the term of seven years. At the end of this period, (when Blake would have reached the age of 21), it was presumed that Blake would become a professional engraver.

While there is no record of any serious disagreement between the two during the period of Blake's apprenticeship, Ackroyd's biography notes that Blake was later to add Basire's name to a list of artistic adversaries - and then cross it out (Ackroyd 1995). This aside, Basire's style of engraving was considered to be old-fashioned at the time, and Blake's instruction in this outmoded form may have had a detrimental effect on his efforts to acquire work or recognition during his lifetime.

After two years, Basire sent him to copy images from the Gothic churches in London. It is possible that this task was set in order to break up a quarrel between Blake and James Parker, his fellow apprentice. Blake's experiences in Westminster Abbey in particular first informed his artistic ideas and style. It must be remembered that the Abbey was a different environment entirely from its more somber modern aspect: it was festooned with suits of armor, painted funeral effigies and varicolored waxworks, and "the most immediate [impression] would have been of faded brightness and colour" (Ackroyd 1995). During the many long afternoons Blake spent sketching in the cathedral, he was occasionally interrupted by the boys of Westminster School, one of whom tormented Blake so much one afternoon that he knocked the boy off a scaffold to the ground, "upon which he fell with terrific Violence." Blake beheld more visions in the Abbey, of a great procession of monks and priests, while he heard "the chant of plain-song and chorale."

The Royal Academy

In 1779, Blake became a student at the Royal Academy in Old Somerset House, near the Strand. The terms of his study required him to make no payment; he was, however, required to supply his own materials throughout the six-year period. There, Blake rebelled against what he regarded as the unfinished style of fashionable painters such as Rubens, championed by the school's first president, Joshua Reynolds. Over time, Blake came to detest Reynold's attitude to art, especially his pursuit of "general truth" and "general beauty." During an address given by Reynolds in which he maintained that the tendency to abstraction is "the great glory of the human mind," Blake reportedly responded, "to generalise is to be an idiot to particularize is alone the distinction of merit." Blake also disliked Reynoldsâ apparent humility, which he held to be a form of hypocrisy. Against Reynoldsâ fashionable oil painting, Blake preferred the Classical exactness of his early influences, Michelangelo and Raphael.

In July 1780, Blake was walking towards Basire's shop in Great Queen Street when he was swept up by a rampaging mob that stormed Newgate Prison in London. The mob was wearing blue cockades (ribbons) on their caps, to symbolize solidarity with the insurrection in the American colonies. They attacked the prison gates with shovels and pickaxes, before setting the building ablaze. The rioters than clambered onto the roof of the prison and tore away at it, releasing the prisoners inside. Blake was reportedly in the very front rank of the mob during this attack, though it is unlikely that he was forced into attendance. More likely, according to Ackroyd, he accompanied the crowd impulsively.

These riots were in response to a Parliamentary bill designed to advance Roman Catholicism. This disturbance, later known as the Gordon riots after Lord George Gordon whose Protestant Association incited the riots, provoked a flurry of paranoid legislation from the government of George III, as well as the creation of the first police force.

Marriage

In 1782, Blake met John Flaxman, who was to become his patron. In the same year he met Catherine Boucher. At the time, Blake was recovering from an unhappy relationship that had ended with a refusal of his marriage proposal. Telling Catherine and her parents the story, she expressed her sympathy, whereupon Blake asked her 'Do you pity me?' To Catherine's affirmative response he himself responded 'Then I love you.' Blake married Catherine, who was five years his junior, on August 18, 1782. Catherine, who was illiterate, signed her wedding contract with an 'X.' Later, Blake taught Catherine to read and write and trained her as an engraver. Throughout his life she would prove to be an invaluable aide to him, helping to print his illuminated works and maintaining his spirits following his numerous misfortunes. Their marriage, though unblessed by children, remained close and loving throughout the remainder of Blake's life.

At this time, George Cumberland, one of the founders of the National Gallery, became an admirer of Blake's work. Blake's first collection of poems, Poetical Sketches, was published in 1783. After his father's death, William and brother Robert opened a print shop in 1784 and began working with radical publisher Joseph Johnson. At Johnson's house, he met some of the leading intellectual dissidents in England, including Joseph Priestley, scientist; Richard Price, philosopher; John Henry Fuseli, a painter with whom Blake became friends; Mary Wollstonecraft, an early feminist; and Thomas Paine, American revolutionary. Along with William Wordsworth and William Godwin, Blake had great hopes for the American and French Revolutions. Blake wore a red liberty cap in solidarity with the French revolutionaries, but despaired with the rise of Robespierre and the Reign of Terror.

Mary Wollstonecraft became a close friend, and Blake illustrated her Original Stories from Real Life (1788). They shared similar views on sexual equality and the institution of marriage. In the Visions of the Daughters of Albion in 1793, Blake condemned the cruel absurdity of enforced chastity and marriage without love, and defended the right of women to complete self-fulfillment. In 1788, at the age of 31, Blake began to experiment with relief etching, which was the method used to produce most of his books of poems. The process is also referred to as illuminated printing, and final products as illuminated books or prints. Illuminated printing involved writing the text of the poems on copper plates with pens and brushes, using an acid-resistant medium. Illustrations could appear alongside words in the manner of earlier illuminated manuscripts. He then etched the plates in acid in order to dissolve away the untreated copper and leave the design standing. The pages printed from these plates then had to be hand-colored in watercolors and stitched together to make up a volume. Blake used illuminated printing for four of his works: the Songs of Innocence and Experience, The Book of Thel, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, and Jerusalem.

Later life and career

Blake's marriage to Catherine remained a close and devoted one until his death. There were early problems, however, such as Catherine's illiteracy and the couple's failure to produce children. At one point, in accordance with the beliefs of the Swedenborgian Society, Blake suggested bringing in a concubine. Catherine was distressed at the idea, and he dropped it. Later in his life Blake sold a great number of works, particularly his Bible illustrations, to Thomas Butts, a patron who saw Blake more as a friend in need than an artist. Around 1800, Blake moved to a cottage at Felpham in Sussex (now West Sussex) to take up a job illustrating the works of William Hayley, a mediocre poet. It was in this cottage that Blake wrote Milton: a Poem (which was published later between 1805 and 1808).

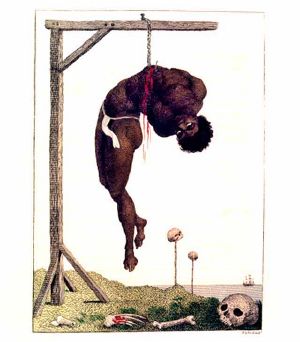

Blake abhorred slavery and believed in racial and sexual equality. Several of his poems and paintings express a notion of universal humanity: "As all men are alike (tho' infinitely various)." He retained an active interest in social and political events for all his life, but was often forced to resort to cloaking social idealism and political statements in protestant mystical allegory. Blake rejected all forms of imposed authority; indeed, he was charged with assault and uttering seditious and treasonable expressions against the King in 1803 but was cleared of the charges in the Chichester assizes.

Blake's views on what he saw as oppression and restriction of rightful freedom extended to the Church. Blake was a follower of Unitarian philosophy, and he is also said to have been the Chosen Chief of the Ancient Druid Order from 1799 to 1827. His spiritual beliefs are evidenced in Songs of Experience (1794), in which Blake showed his own distinction between the Old Testament God, whose restrictions he rejected, and the New Testament God (Jesus Christ), whom he saw as a positive influence.

Blake returned to London in 1802 and began to write and illustrate Jerusalem (1804-1820). George Cumberland introduced him to a young artist named John Linnell. Through Linnell he met Samuel Palmer, who belonged to a group of artists who called themselves the Shoreham Ancients. This group shared Blake's rejection of modern trends and his belief in a spiritual and artistic New Age. At the age of sixty-five Blake began work on illustrations for the Book of Job. These works were later admired by John Ruskin, who compared Blake favorably to Rembrandt.

William Blake died in 1827 and was buried in an unmarked grave at Bunhill Fields, London. Much later, a proper memorial was erected for Blake and his wife. Perhaps Blakeâs life is best summed up by his statement that "The imagination is not a State: it is the Human existence itself." Blake is also recognized as a Saint in Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica. The Blake Prize for Religious Art was established in his honor in Australia in 1949.

Works

Blake was amazingly productive during his lifetime, despite his financial difficulties and the lack of recognition that troubled him throughout his career. His complete poetry is a massive volume of nearly one thousand pages. Most of these poems were illuminated, so for every page of text Blake also printed canvases upon canvases of paintings.

Blake's tremendous output is partly one of the reasons why he has been so often misunderstood. Blake conceived of all his poetry as being analogous to the Bible, in that it was made of disparate elements that are nonetheless part of a coherent narrative. Blake's works can in fact be broken up into categories similar to those in the Bible: there are Blake's shorter and accessible "wisdom books," such as The Marriage of Heaven and Hell; his popular Songs of Innocence and Experience; and his immense and tremendously challenging "prophetic books," such as the epic poem Jerusalem and the book-length chronicle The Four Zoas that to this day have been largely neglected due to their complexity. All of these works, however, are in conversation with one another, because Blake saw himself as constantly writing and rewriting the same poems. Most of his works are, in a sense, unfinished, because in the midst of writing one book Blake often discovered that he was running into a problem that could only be resolved by taking off in a completely different direction.

Part of the difficulty with reading any of Blake's works (outside his early, short lyrics) are that not only are his poems in conversation with one another, but are also part of an extensive mythology that Blake himself imagined. Take for instance this brief excerpt from Milton: Book The First:

Mark well my words! they are of your eternal salvation:

Three Classes are Created by the Hammer of Los, & Woven By Enitharmons Looms when Albion was slain upon his Mountains And in his Tent, thro envy of Living Form, even of the Divine Vision And of the sports of Wisdom in the Human Imagination Which is the Divine Body of the Lord Jesus. blessed for ever. Mark well my words. they are of your eternal salvation: Urizen lay in darkness & solitude, in chains of the mind lock'd up Los seizd his Hammer & Tongs; he labourd at his resolute Anvil

Among indefinite Druid rocks & snows of doubt & reasoning.

Such names as Urizen, Los, Enitharmon, and even Albion (an ancient name of England) are all members of a menagerie that make up Blake's mythos. They each stand for different aspects of the ideal human being (what Blake called the "Eternal Human Imagination Divine"), that through strife, pity, and jealousy have been torn apart and become individual deities, (analogous, in a way, to the Greek gods) each lacking the aspects needed to make them whole.

Although this technique strikes the initial reader as impenetrably abstruseâand was the principle reason why most of Blake's contemporaries considered him insaneâone finds, reading across Blake's vast poetic output, that there is a "fearful symmetry" (as Northrop Frye called it, borrowing a line from Blake's famous poem The Tyger) running throughout Blake's convoluted mythos. Familiarity with Blake's mythology (there are countless glossaries and handbooks available now online and in print), shows that Blake's poetryâfrom its deceptively simple beginnings to its impossibly complex endsâis the work of a profound mind grappling with immense philosophical inquiries.

Blake, although often labeled a Romantic poet, in reality transcended romanticism. Nor was he, really, akin to any of the other schools of English poetry that would come before or after him. Blake was truly a literature unto himself.

Bibliography

Illuminated Books

- c.1788: All Religions are One

- There is No Natural Religion

- 1789: Songs of Innocence

- The Book of Thel

- 1790-1793: The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

- 1793: Visions of the Daughters of Albion

- America: a Prophecy

- 1794: Europe: a Prophecy

- The First Book of Urizen

- Songs of Experience (The sequel to Songs of Innocence, with many of its poems intended as counterpoints from the Fallen world to those in the first book, this was Blake's only Illuminated book to achieve even limited success in his lifetime. It includes the poems The Tyger and The Sick Rose)

- 1795: The Book of Los

- The Song of Los

- The Book of Ahania

- c.1804-c.1811: Milton: a Poem

- 1804-1820: Jerusalem: The Emanation of The Giant Albion

Non-Illuminated Material

- Never seek to tell thy love

- Tiriel (circa 1789)

Illustrated by Blake

- 1788: Mary Wollstonecraft, Original Stories from Real Life

- 1797: Edward Young, Night Thoughts

- 1805-1808: Robert Blair, The Grave

- 1808: John Milton, Paradise Lost

- 1819-1820: John Varley, Visionary Heads

- 1821: R.J. Thornton, Virgil

- 1823-1826: The Book of Job

- 1825-1827: Dante, The Divine Comedy (Blake died in 1827 with these watercolors still unfinished)

On Blake

- Jacob Bronowski (1972). William Blake and the Age of Revolution. Routledge and K. Paul. ISBN 0710072775

- Jacob Bronowski (1967). William Blake, 1757-1827; a man without a mask. Haskell House Publishers.

- S. Foster Damon (1979). A Blake Dictionary. Shambhala. ISBN 0394736885.

- Northrop Frye (1947). Fearful Symmetry. Princeton Univ Press. ISBN 0691061653.

- Peter Ackroyd (1995). Blake. Sinclair-Stevenson. ISBN 1856192784.

- E.P. Thompson (1993). Witness against the Beast. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521225159.

- Victor N. Paananen (1996). William Blake. Twayne Publishers. ISBN 0805770534.

- George Anthony Rosso, Jr. (1993). Blake's Prophetic Workshop: A Study of The Four Zoas. Associated University Presses. ISBN 0838752403.

- G.E. Bentley Jr. (2001). The Stranger From Paradise: A Biography of William Blake. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300089392.

- David V. Erdman (1977). Blake: Prophet Against Empire: A Poet's Interpretation of the History of His Own Times. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0486267199.

- James King (1991). William Blake: His Life. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312075723.

- W.J.T. Mitchell (1978). Blake's Composite Art: A Study of the Illuminated Poetry. Yale University Press. ISBN 0691014027.

- Peter Marshall (1988). William Blake: Visionary Anarchist. ISBN 090038477.

- Malkin, A Father's Memories of his Child. (1806)

- Alexander Gilchrist. Life and Works of William Blake. (second edition, London, 1880)

- Algernon Charles Swinburne. William Blake: A Critical Essay. (London, 1868)

- W.M. Rossetti, ed. Poetical Works of William Blake. (London, 1874)

- Basil de SĂ©lincourt, William Blake. (London, 1909)

- A.G.B. Russell, Engravings of William Blake. (1912)

- W. B. Yeats, Ideas of Good and Evil. (1903), contains essays.

- Joseph Viscomi. Blake and the Idea of the Book. Princeton Univ. Press, 1993. ISBN 069106962X.

Inspired by Blake

- The Fugs put Ah, Sunflower and other Blake poems to music. Also used a Blake painting as part of the cover to the bootleg record, Virgin Fugs.

- Tyger, an album by electronic music artists Tangerine Dream, features a number of William Blake poems set to music.

- Tiger (ca. 1928), a tone-cluster piano piece by Henry Cowell

- Red Dragon, a novel by Thomas Harris, whose title refers to Blake's painting The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed in the Sun, the original of which is eaten by the novel's antihero.

- The 1981 film The Evil Dead, directed by Sam Raimi, also contains Blake's painting The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed in the Sun,as a page in the Book of the Dead.

- Themes from William Blake's The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, an album by the Norwegian musical group Ulver from 1998, utilizes the complete text of the Blake poem lyrically.

- The Songs of Innocence and Experience have been set to music by Ralph Vaughan-Williams, and more recently by William Bolcom. Albums using them as lyrics include Greg Brown's "Songs of Innocence and Experience" and Jah Wobble's "The Inspiration of William Blake." Allen Ginsberg also released an album of Blake songs.

- A series of poems and texts chosen by Peter Pears from Songs of Innocence, Songs of Experience, Auguries of Innocence, and The Marriage of Heaven and Hell was made into the song cycle, Songs and Proverbs of William Blake, by Benjamin Britten in 1965.

- The Sick Rose from Songs of Experience is one of the poems by several authors set to music by Benjamin Britten in Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings.

- Spring, by Finn Coren

- The World of Tiers books by Philip José Farmer

- Quotations from Blake form the climax of Jerry Springer - The Opera

- Dead Man, a film written and directed by Jim Jarmusch, features a character named William Blake and includes many references to Blake's work.

- Love's Secret Domain an electronic album by Coil, quotes Blake numerous times in the lyrics. The title track is also a reinterpretation of The Sick Rose. Various other albums by Coil carry many Blake references and allusions.

- The book The Doors of Perception by Aldous Huxley draws its title from a line in Blake's The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. The title of Huxley's book, in turn, inspired the naming of the rock band The Doors who turned Blake's "Auguries of Innocence" into their "End of the Night."

- The Amber Spyglass, the third book from the collection His Dark Materials, by Philip Pullman, has several quotations from Blake's works.

- The Chemical Wedding album by Bruce Dickinson.

- Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience, album by David Axelrod

- The character Blake Williams in the Schrödinger's Cat trilogy by Robert Anton Wilson is named after William Blake.

- Grendel, by John Gardner, quotes a verse from Blake's "The Mental Traveller" before the book begins. It also has many references to Blake throughout the novel.

- William Blake also is the name of the main protagonist in Jim Jarmusch's Movie "Dead Man," where Blake's "tongue will be the gun" and where the poetry of the author Blake plays a crucial role in understanding the movie's logic.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Marshall, Peter. William Blake: Visionary Anarchist, revised ed. Freedom Press, [1988] 1994. ISBN 0900384778

External links

All links retrieved May 6, 2023.

- William Blake - Cybersongs of Innocence

- The William Blake Archive

- Poetry Archive: 169 poems of William Blake

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.