Encyclopedia, Difference between revisions of "Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky" - New World

| Line 145: | Line 145: | ||

===Symphonies=== | ===Symphonies=== | ||

| − | Tchaikovsky's earlier [[symphony|symphonies]] are generally optimistic works of | + | Tchaikovsky's earlier [[symphony|symphonies]] are generally optimistic works of a |

| − | + | nationalist character; the latter are more dramatic, particularly ''The Fourth'', ''Fifth'', and ''Sixth'', recognized for the uniqueness of their format. He also left behind four orchestral suites originally intended as a "symphony" but was persuaded to alter the title. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * ''Symphony No. 1 in G Minor,'' Op. 13, ''Winter Daydreams'' – 1866 | |

| + | * ''Symphony No. 2 in C Minor,'' Op. 17, ''Little Russian'' – 1872 | ||

| + | * ''Symphony No. 3 in D Minor,'' Op. 29, ''Polish'' (for its use of [[polonaise]]) – 1875 | ||

| + | |||

| + | * ''Symphony No. 4 in F Minor,'' Op. 36 – 1877–1878 | ||

| + | :Conceived after he fled his wife and began friendship with von Meck. He dedicated it to von Meck, describing the symphony to her as “ours”, confessing “how much I thought of you with every bar.” <ref> Ewen, 1966 p. 751 ''The Complete Book of Classical Music'' </ref> | ||

| + | * Manfred, Symphony in B Minor, Op. 58 – 1885 | ||

| + | :Inspired by [[George Gordon Byron|Byron]]'s poem "Manfred" | ||

| + | * ''Symphony No. 5 in E minor,'' Op. 64 – 1888 | ||

| + | :Written while haunted by fears of the work’s failure, having lost confidence in his musical prowess. The Fifth is interpreted as a story of the Fate and labeled by critics as his most unified symphony in purpose and design. | ||

| + | * ''Symphony No. 7'': see [[#Concerti|below]], ''Piano Concerto No. 3'') | ||

| + | * ''Symphony No. 6 in B Minor,'' Op. 74, ''Pathétique'' – 1893 | ||

| + | :Composed amidst the torment of depression; considered as the most pessimistic and dramatic of his pieces. He considered it the best and most sincere work he has written and was very satisfied and proud of it. Being the most tragic piece he ever wrote, originally it was to be entitled ''The Program Symphony'', which was interpreted by some as an effort at his own requiem. He confessed that he repeatedly burst into tears when writing it. This is his greatest symphony and his most popular as well as the most celebrated symphony in Russian music and possibly in Romantic music. | ||

=== Concerti === | === Concerti === | ||

| − | * | + | * ''Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-flat Minor,'' Op. 23 – 1874–1875 |

| − | * | + | : One of the most popular piano concertos ever written, dedicated to the pianist [[Nikolai Grigoryevich Rubinstein]]. When he played it for Rubinstein in an empty classroom in the Conservatory, Rubinstein was silent, and when the performance ended, he told Tchaikovsky that it was worthless and unplayable for its commonplace passages that were beyond improvement, for its triviality and vulgarity, and for borrowing from other composers and sources. Tchaikovsky's response was, "I shall not change a single note, and I shall publish the concerto as it is now. And this, indeed, I did." <ref> Ewen, 1966 p. 745 ''The Complete Book of Classical Music'' </ref> [[Hans von Bülow]] introduced it to the world in [[Boston, Massachusetts]] in 1875, with a phenomenal success. Rubinstein later admitted his error of judgment and included the work in his repertoire. |

| − | * | + | * ''Violin Concerto in D Major,'' Op. 35 – 1878 |

| − | * | + | :Composed in less than a month in 1878 but its first performance was delayed until 1881 because Leopold Auer, the violinist to whom Tchaikovsky had intended to dedicate it, refused to perform it for its technical difficulty. Austrian violinist Adolf Brodsky later played it to a public that was apathetic due to the violin’s out-of-fashion status. Presently one of the most popular concertos for the violin. |

| + | * ''Piano Concerto No. 2,'' Op. 44 – 1879 | ||

| + | * ''Piano Concerto No. 3'' – 1892 | ||

| + | : Commenced after the ''Symphony No. 5,'' it was intended to be the next numbered symphony but he set it aside after nearly finishing the first movement. In 1893, after beginning work on ''Pathétique'', he reworked the sketches of the first movement and completed the instrumentation to create a piece for piano and orchestra known as ''Allegro de concert'' or ''Konzertstück'' (published posthumously as Op. 75). Tchaikovsky also produced a piano arrangement of the slow movement (Andante) and last movement (Finale) of the symphony. He turned the scherzo into another piano piece, the ''Scherzo-fantasie in E-flat minor'', Op. 72, No. 10. After his death, composer Sergei Taneyev completed and orchestrated the ''Andante and Finale'', published as ''Op. 79''. A reconstruction of the original symphony from the sketches and various revisions was accomplished during 1951–1955 by the Soviet composer Semyon Bogatyrev, who brought the symphony into finished, fully orchestrated form and issued the score as ''Symphony No 7 in E-flat major''.<ref>Wiley, Roland. 'Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Il′yich, §6(ii): Years of valediction, 1889–93: The last symphony'; Works: solo instrument and orchestra; Works: orchestral, Grove Music Online (Accessed 07 February 2006), <http://www.grovemusic.com> (subscription required). Brown, David. ''Tchaikovsky: the Final Years (1885-1893).'' New York: W.W. Norton, 1991, pp. 388-391, 497.</ref> | ||

| − | + | ====For Orchestra==== | |

| − | ====For | ||

[[Image:1812 overture.jpg|thumb|250px|The 1812 overture complete with cannon fire was performed at the 2005 Classical Spectacular]] | [[Image:1812 overture.jpg|thumb|250px|The 1812 overture complete with cannon fire was performed at the 2005 Classical Spectacular]] | ||

| − | * | + | * ''Romeo and Juliet'' ''Fantasy Overture'' – 1869, revised in 1870 and 1880 |

| − | * | + | :Written on suggestion from Balakirev. Balakirev was not satisfied with its first version and suggested numerous changes; after the revision, he declared that it was Tchaikovsky’s best work. Later on Tchaikovsky revised it again, which is the version enjoyed by modern audiences. Its melodies are used in movies and commercials. |

| − | * | + | * ''The Tempest'' "Symphonic Fantasia After Shakespeare,” Op. 18 – 1873 |

| − | * | + | * ''Slavonic March'' (''Marche Slave''), Op. 31 – 1876 |

| − | * | + | :Written for a beneficial concert for Serbian soldiers wounded in the war against Turkey, it expresses his sympathies for the Slavs and predicts their ultimate victory. The melody borrows from an old Serbian song and the Russian National Anthem. Commonly referenced in cartoons, commercials, and the media. |

| − | + | * ''Francesca da Rimini,'' Op. 32 – 1876 | |

| − | * | + | :The inspiration came from Dante Aligieri’s Inferno. He provided a program for it, explaining that the first section describes the gateway to the Inferno and the agonies suffered by those who reside there, while the middle part relates the tragic love story of Paolo and Francesca. The third part is a return to the Inferno. |

| − | * | + | * ''Capriccio Italien,'' Op. 45 – 1880 |

| − | * | + | :A traditional caprice (capriccio) in an Italian style. Tchaikovsky stayed in [[Italy]] from the late 1870s to early 1880s and during the various festivals he heard many themes featured in the piece. It has a lighter character than many of his works, even "bouncy" in places, and is often performed today in addition to the ''1812 Overture''. The title is a linguistic hybrid: it contains an Italian word ("Capriccio") and a French word ("Italien"). A fully Italian version would be ''Capriccio Italiano''; a fully French version would be ''Caprice Italien''. |

| − | + | * ''Serenade in C for String Orchestra,'' Op. 48 – 1880 | |

| − | + | :The first movement, in the form of a [[sonatina]], was a homage to Mozart. The second movement is a [[waltz]], followed by an [[elegy]] and a spirited Russian finale, Tema Russo. | |

| + | * ''1812 Overture,'' Op. 49 – 1880 | ||

| + | : Written reluctantly to commemorate the Russian victory over [[Napoleon]] in the [[Napoleonic Wars]]. Known for its traditional [[Music of Russia|Russian]] themes, such as the old Tsarist National Anthem, as well as its triumphant and bombastic coda at the end, which makes use of 16 cannon shots and a [[chorus]] of church bells. | ||

| + | * ''Coronation March,'' Op. 50 – 1883 | ||

| + | :The mayor of Moscow commissioned this piece for performance in May 1883 at the coronation of [[Aleksandr III of Russia|Alexander III]]. | ||

| + | * ''Mozartiana'', op. 61 – 1887 | ||

| + | :Devoted to the composer he admired above all ; adapts for orchestra some of Mozart’s less familiar compositions. He wished to revive the study of those “little masterworks, whose succinct form contains incomparable beauties.”<ref> Ewen, 1966 p. 759 ''The Complete Book of Classical Music'' </ref> | ||

| − | ====For | + | ====For Orchestra, Choir and Vocal Soloists==== |

| − | * | + | * ''Snegurochka (The Snow Maiden)'' – 1873 |

| + | :Incidental music for [[Alexander Ostrovsky]]'s play of the same name. | ||

| − | ====For | + | ====For Orchestra, Soprano, and Baritone==== |

| − | * | + | * ''Hamlet'' – 1891 |

| + | :Incidental music for Shakespeare's play. | ||

| − | ====For | + | ====For Choir, Songs, Chamber Music, and For Solo Piano and Violin==== |

| − | * | + | * ''String Quartet No. 1 in D Major,'' Op. 11 – 1871 |

| − | * | + | * ''Variations on a Rococo Theme for Cello and Orchestra,'' Op. 33. – 1876 |

| − | * | + | :Reflects his adoration of [[Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart|Mozart]] and [[Baroque]] music. |

| − | * ''Three pieces: Meditation, Scherzo and Melody | + | * Piano suite ''The Seasons,'' Op. 37a – 1876 |

| − | * | + | * ''Three pieces: Meditation, Scherzo and Melody'', Op. 42, for violin and piano |

| − | * | + | * ''Russian Vesper Service,'' Op. 52 – 1881 |

| − | * | + | * ''Piano Trio in A minor,'' Op. 50 – 1882 |

| − | * | + | :Commissioned by Madame von Meck as a chamber music work for her household trio, including pianist [[Claude Debussy]]. At the same time, it is an elegy on the death of Nikolai Rubinstein. |

| + | * ''Dumka'', Russian rustic scene in C minor for piano, Op. 59 – 1886 | ||

| + | * String sextet ''Souvenir de Florence,'' Op. 70 – 1890 | ||

For a complete list of works by opus number, see [http://w3.rz-berlin.mpg.de/cmp/tchaikovsky_works.html]. For more detail on dates of composition, see [http://www.geocities.com/Vienna/5648/DCalend.htm]. | For a complete list of works by opus number, see [http://w3.rz-berlin.mpg.de/cmp/tchaikovsky_works.html]. For more detail on dates of composition, see [http://www.geocities.com/Vienna/5648/DCalend.htm]. | ||

Revision as of 00:57, 29 January 2007

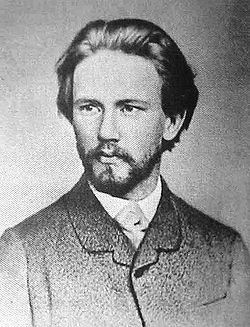

Pyotr (Peter) Ilyich Tchaikovsky (Russian: Пётр Ильич Чайкoвский, Pjotr Il’ič Čajkovskij; listen ▶ (7 May [O.S. 25 April] 1840 – 6 November [O.S. 25 October] 1893), also transliterated Piotr Ilitsch Tschaikowski, Petr Ilich Tschaikowsky, Piotr Illyich Tchaikovsky, as well as many other versions, was a Russian composer of the Romantic era. Although not a member of the group of nationalistic composers usually known in English-speaking countries as 'The Five', his music has come to be known and loved for its distinctly Russian character as well as for its rich harmonies and stirring melodies. His works, however, were much more western than those of his Russian contemporaries as he effectively used international elements in addition to national folk melodies.

Early life

Pyotr Tchaikovsky was born on April 25, 1840 (Julian calendar) or May 7 (Gregorian calendar) in Votkinsk, a small town in present-day Udmurtia (at the time the Vyatka Guberniya under Imperial Russia), the son of a mining engineer in the government mines, who had the rank of major-general, and the second of his three wives, Alexandra, a Russian woman of French ancestry. He was the older brother (by some ten years) of the dramatist, librettist, and translator Modest Ilyich Tchaikovsky. The family name came from his Kazakh great-grandfather, who could imitate the call of a seagull (a tchaika) and had fought for Peter the Great when he defeated teh Swedes in 1709. The family enjoyed music and played Mozart, Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti on a large musical box called an orchestrion. Tchaikovsky remarked later on that he was fortunate not to have been brought up in a very musical family that would spoil him with music imitating Beethoven. Tchaikovsky received piano lessons from a freed serf.

Musically precocious, Pyotr began piano lessons at the age of five, and in a few months he was already proficient at Friedrich Kalkbrenner's composition Le Fou. In 1850, his father was appointed director of the St Petersburg Technological Institute. There, the young Tchaikovsky obtained an excellent general education at the School of Jurisprudence, and furthered his instruction on the piano with the director of the music library. Also during this time, he made the acquaintance of the Italian master Luigi Piccioli, who influenced the young man away from German music, and encouraged the love of Rossini, Bellini, and Donizetti. His father indulged Tchaikovsky's interest in music by funding studies with Rudolph Kündinger, a well-known piano teacher from Nuremberg. Under Kündinger, Tchaikovsky's aversion to German music was overcome, and a lifelong affinity with the music of Mozart was seeded. When his mother died of cholera in 1854, the 14-year-old composed a waltz in her memory.

Tchaikovsky left school in 1858 and received employment as an under-secretary in the Ministry of Justice at the time when the Ministry was drafting legislation for emancipation of hte serfs and implmentation of various reforms. He soon joined the Ministry's choral group. The atmosphere was one of intellectual excitement but he wrote in a letter to his sister that he had hoped to obtain a different post with higher income yet fewer duties. The cultural and musical life of St. Petersburg was rich, and the composer made serveral friendhips, among them with an openly homosexual poet Alexei Apukhtin and with a middle-aged singing teacher who dyed his hair and wore rouge.

In 1861, he befriended a fellow civil servant who had studied with Nikolai Zaremba, who urged him to resign his position and pursue his studies further. Not ready to give up employment, Tchaikovsky agreed to begin lessons in musical theory with Zaremba. The following year, when Zaremba joined the faculty of the new St Petersburg Conservatory, Tchaikovsky followed his teacher and enrolled, but still did not give up his post at the ministry, until his father consented to support him. From 1862 to 1865, Tchaikovsky studied harmony, counterpoint and the fugue with Zaremba, and instrumentation and composition under the director and founder of the Conservatory, Anton Rubinstein. However, neither Anton Rubinstein nor Cesar Cuit appreciated his graduation cantata Ode to Joy.

Musical career

ewen: hies early works gave every indication of serving the cause of Russian nationalism: Little Russian, The Voyevoda, The Oprichnik, Vakula the SMith made copious and effective use of Russian folk songs and dances. the national element is still pronounced in teh first acto fo Eugene Onegin. then he began drawing away from folk sources toward a mroe cosmpolitan style, allowed himself to be influenced by German Romanticism; he sought to bring to his writing the elegance, sophistsication, and good breeding of the WEstern world. For these strong European leanings he was violently attacked by the die-hard nationalists. THey found him a negation of the principles for which they stood.

Yet it was Tchaikovsky who was the first to bring about a genuine appreciation of Russian music in the Western world and he is the one who represents Russian music. Even though he abandoned Russian nationalism, nationalism never abandoned him, as evidenced in his Russian melodies and rhythmsas well as the Russian tendency toward brooding and melancholia dominated his moods.

"As to the Russian element in my music generally, its melodic and hamronic relation to folk music—I grew up in a quiet place and was drenched from the earliest childhood with the wonderful beauty of Russian popular songs. I am, therefore, passionately devoted to every expression of the Russian spirit. In brief, I am a Russian, through and through."[1]

Stravinsky: "Tchaikovsky's music, which does not appear Russian to everybody, is often more profoundly Russian than music which has long since been awarded the facile label of Muscovite picturesqueness. THis music is quite as Russian as Pushkin's verse or Glinka's song. Whilst not specially cultivating in his art the 'soul of the Russian peasonat,' Tchaikovsky drew unconsciously from the true, popular sources of our race." [2]

rephrased - An interesting phenomenon occurred: Russian contemporaries attacked him for being too European, while Europeans criticized him for being too russian. His sentimentality that tends to slide towards bathos as well as his style, seen by some as superficial at times, and a pathos and pessimism that boil down to hysteria, and melancholia that evokes self-pity. (this is evident in works of other Eastern Europeans as well). Although these are credible accusations to a degree, he is the most popular Russian composer for the ability to speak from heart to heart and convey beuaty in sadness.

Richard Anthony Leonard: ...expressive and communicative in the highest degree. That is is also comparatively easy to absorb and appreciate shouodl be accounted among its virtues instead of its faults." [3]

After graduating, Tchaikovsky was approached by Anton Rubinstein's younger brother Nikolai Grigoryevich Rubinstein to become professor of harmony, composition, and the history of music. Tchaikovsky gladly accepted the position, as his father had retired and lost his property. The next ten years were spent teaching and composing. Teaching proved taxing, and in 1877 he suffered a breakdown. After a year off, he attempted to return to teaching, but retired his post soon after. He spent some time in Italy and Switzerland, but eventually took residence with his sister, who had an estate just outside Kiev.

Tchaikovsky took to orchestral conducting after filling in at a performance in Moscow of his opera The Enchantress (Russian: Чародейка) (1885-7). Overcoming a life-long stage fright, his confidence gradually increased to the extent that he regularly took to conducting his pieces.

Tchaikovsky visited America in 1891 in a triumphant tour to conduct performances of his works. On May 5, he conducted the New York Music Society's orchestra in a performance of Marche Solennelle on the opening night of New York's Carnegie Hall. That evening was followed by subsequent performances of his Third Suite on May 7, and the a cappella choruses Pater Noster and Legend on May 8. The US tour also included performances of his Piano Concerto No. 1 and Serenade for Strings.

Just nine days after the first performance of his Symphony No. 6, Pathétique, in 1893, in St Petersburg, Tchaikovsky died (see section below).

Some musicologists (e.g. Milton Cross, David Ewen) believe that he consciously wrote his Sixth Symphony as his own Requiem. In the development section of the first movement, the rapidly progressing evolution of the transformed first theme suddenly "shifts into neutral" in the strings, and a rather quiet, harmonized chorale emerges in the trombones. The trombone theme bears absolutely no relation to the music that preceded it, and none to the music which follows it. It appears to be a musical "non sequitur", an anomaly — but it is from the Russian Orthodox Mass for the Dead, in which it is sung to the words: "And may his soul rest with the souls of all the saints." Tchaikovsky was interred in Tikhvin Cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery in St Petersburg.

His music included some of the most renowned pieces of the romantic period. Many of his works were inspired by events in his life.

Personal life

He was tall, distinguished and elegant with a diastrous marriage, relattionship with a patroness, alcoholism, and likeness for young boys. His exhibitionism in music was regarded as defuncty and vulgar at his time, yet his popularity beguiles experts' opinions because the public has loved his music regardless the judgment expressed by the cognoscenti. his During his education at the School of Jurisprudence, he was infatuated with a soprano, but she married another man. One of his conservatory students, Antonina Miliukova, a neurotic woman, who in fell on her knees in adoration before him during her first interview with him, began writing him passionate letters around the time that he had made up his mind to "marry whoever will have me." He did not even remember her from his classes, but her letters were very persistent, and he hastily married her on July 18, 1877. In a letter to his brother he mentioned that he did not love her but wanted to make a statement to quell the rumors that he was homosexual. Within days, while still on their honeymoon, he deeply regretted his decision. Two weeks after the wedding the composer supposedly attempted suicide by putting himself into the freezing Moscow River, and then he left Russia for a yearlong travel around Europe. He never returned to his wife after that but did send her a regular allowance through the years. Though they never again cohabitated with each other, they remained legally married until his death. Three years after his death, Antonina was consigned to a mental hospital.

He would spend many summers with his sister Sasha in a village in the Ukraine where she lived with her husband. He enjoyed the local woods and fields, picked violets and lily-of-the-valley, visit a village fair, and wrote an early version of Swan Lake for the children. The composer's homosexuality, as well as its importance to his life and music, has long been recognized, though any proof of it was suppressed during the Soviet era.[4] Although some historians continue to view him as heterosexual, many others — such as Rictor Norton and Alexander Poznansky — accept that some of Tchaikovsky's closest relationships may have been homosexual, (citing his servant Aleksei Sofronov and perhaps even his nephew, Vladimir "Bob" Davydov.) Evidence that Tchaikovsky was homosexual is drawn from his letters and diaries, as well as the letters of his brother, Modest, who was also homosexual.

A far more influential woman in Tchaikovsky's life was a wealthy widow and a musical dilettante, Nadezhda von Meck, with whom he exchanged over 1,200 letters between 1877 and 1890. At her insistence they never met; they did encounter each other on two occasions, purely by chance, but did not converse. As well as financial support in the amount of 6,000 rubles a year, she expressed interest in his musical career and admiration for his music. The relationship evolved into love, and Tchaikovsky spoke to her freely about his innermost feelings and aspirations. However, after 13 years she ended the relationship unexpectedly, claiming bankruptcy. Other sources attribute this to the social gap between them and her love of her children, which she would not jeopardize by any means. He sent an an anxious letter pleading for the continued friendship, stating that he was no longer in need of her finances, but his letter went unanswered. Then he discovered that she had not suffered any reverse in fortune. The two were related by marriage in their families— one of her sons, Nikolay, was married to Tchaikovsky's niece Anna Davydova.During this period, Tchaikovsky had already achieved success throughout Europe and by 1891, even greater accolades in the United States, where he was the conductor of his 1812 Overture at the opening night of Carnegie Hall on May 5th, 1891.

Upon return to Russia, his spleen grew to the point that he thought he was on the verge of lunacy. Tchaikovsky's life is the subject of Ken Russell's poorly researched and highly fictionalized motion picture The Music Lovers (1970). Two other motion pictures were based on his life - the low-budgeted, sanitized and also highly fictionalized Song of My Heart, released in 1948, and the 1969 Russian-language "Tchaikovsky" , which was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

His last name derives from the word chaika (чайка), meaning seagull in a number of Slavic languages. His family origins may not have been entirely Russian. In an early letter to Nadezhda von Meck, Tchaikovsky wrote that his name was Polish and his ancestors were "probably Polish." (In fact, the Polish equivalent of his name, Czajkowski, is a not uncommon Polish surname.)

Tchaikovsky's death

Until recent years it had been generally assumed that Tchaikovsky died of cholera after drinking contaminated water, particularly because he was careless enough to drink unboiled water during a cholera epidemic. However, a controversial theory published in 1980 by Aleksandra Orlova and based only on oral history (i.e., without documentary evidence), explains Tchaikovsky's death as a suicide.

In this account, Tchaikovsky committed suicide by consuming small doses of arsenic following an attempt to blackmail him over his homosexuality. His alleged death by cholera (whose symptoms have some similarity with arsenical poisoning) is supposed to have been a cover for this suicide. According to the theory, Tchaikovsky's own brother Modest Tchaikovsky, also homosexual, helped conspire to keep the secret. There are many circumstantial events that some say lend credence to the theory, such as wrong dates on the death certificate, conflicting testimony from Modest and the doctor about the timeline of his death, the fact that Tchaikovsky's funeral was open casket, and that the sheets from his deathbed were merely laundered instead of being burned. There are also passages in Rimsky-Korsakov's autobiography years later about how people at the funeral kissed Tchaikovsky on the face, even though he had died from cholera. These passages were deleted by Russian authorities from later editions of Rimsky-Korsakov's book.

The suicide theory is hotly disputed by others, including Alexander Poznansky, who argues that Tchaikovsky could easily have drunk tainted water because his class regarded cholera as a disease that afflicted only poor people, or because restaurants would mix cool boiled water with unboiled; that the circumstances of his death are entirely consistent with cholera; and that homosexuality ("gentlemanly games") was widely tolerated among the upper classes of Tsarist Russia. To this day, no one knows how Tchaikovsky truly died.

The English composer Michael Finnissy has composed a short opera, Shameful Vice, about Tchaikovsky's last days and death.

Musical works

Songs

- "Again, as Before, Alone," op. 73, no. 6

- "Deception," op. 65, no. 2

- "Don Juan's Serenade," op. 38, no. 1

- "Gypsy's Song," op. 60, no. 7

- "I Bless You, Forests," op. 47, no. 5

- "If I had Only Known," op. 47, no. 1

- "In This Moonlight," op. 73, no. 3

- "It Was in Early Spring," op. 38, no. 2

- "A Legend" ("Christ in His Garden"), op. 54, no. 5

- "Lullaby," op. 54, no. 1

- "None But the Lonely Heart," op. 6, no. 6

- "Not a Word, O My Friend," op. 6, no. 2

- "Only Thou," op. 57, no. 6

- "Pimpinella," op. 38, no. 6

- "Tears," op. 65, no. 5

- "Was I Not a Little Blade of Grass," op. 47, no. 7

- "We Sat Together," op. 73, no. 1

- "Why?" op. 6, no. 5

Tchaikovsky’s song-writing methods came under the ax of his fellow composers and contemporaries for altering the text of the songs to suit his melody, inadequacy of his musical declamation, carelessness, and outdated techniques. Cesar Cui was at the helm of these criticisms, and Tchaikovsky's dismissal was very insightful: "Absolute accuracy of musical declamation is a negative quality, and its importance should not be exaggerated. What does the repetition of words, even of whole sentences, matter? There are cases where such repetitions are completely natural and in harmony with reality. Under the influence of strong emotion a person repeats one and the same exclamation and sentence very often.... But even if that never happened in real life, I should feel no embarrassment in impudently turning my back on 'real' truth in favor of 'artistic' truth."[5]

Edwin Evans found his melodies a blend of two cultures: Teutonic and Slavonic, as his melodies are more emotional than those found in songs originating in Germany and express more of the physical than the intellectual beauty.[6] He was an outstanding lyricist, well versed in a plethora of styles, moods, and atmosphere.

Ballets

Although Tchaikovsky is well known for his ballets, only the last two were appreciated by his contemporaries.

- (1875–1876): Swan Lake, Op. 20

- His first ballet was first performed (with some omissions) at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow in 1877, with a fiasco, as he was forced to delete some passages that were then replaced with inferior ones. It was only in 1895, when the original deleted parts were restored in a revival by choreographs Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov that the ballet was recognized for its eminence.

- (1888–1889): The Sleeping Beauty, Op. 66

- Tchaikovsky considered this one of his best works. It was commissioned by the director of the Imperial Theatres Ivan Vsevolozhsky and first performed in January1890, at the Mariinsky Theatre in St Petersburg.

- (1891–1892): The Nutcracker, Op. 71

- He was less satisfied with this, his last, ballet, likewise commissioned by Vsevolozhsky, worked on it reluctantly. It makes use of celesta as the solo instrument in the "Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy" in Act II, an instrument also employed in The Voyevoda. ^ This was the only ballet from which Tchaikovsky himself derived a suite (the suites that followed the other ballets were devised by other composers). The Nutcracker Suite is often mistaken for the ballet, but it consists of only eight selections from the score intended for concert performance.

Operas

Tchaikovsky completed ten operas, of which one has been largely mislaid and the other exists in two disparate versions. The Western audiences find most delight in Eugene Onegin and The Queen of Spades.

- Voyevoda (Воевода – The Voivode), Op. 3 – 1867–1868

- Tchaikovsky destroyed the score, which was reconstructed from sketches and orchestral parts posthumously.

- Undina (Ундина or Undine) – 1869

- It was never completed. He revised its Second Symphony twice but did not alter the second movement. Only a march sequence saw the light of day; the rest he destroyed.

- The Oprichnik] (Опричник) – 1870–1872

- Premiered in April 1874 in Saint Petersburg|

- Vakula the Smith (Кузнец Вакула – Kuznets Vakula), Op. 14 – 1874

- Later revised as Cherevichki, premiered in December 1876 in Saint Petersburg

- Eugene Onegin (Евгений Онегин – Yevgeny Onegin), Op. 24 – 1877–1878

- Premiered in March 1879 at the [Moscow Conservatory. Based on the novel in verse by Alexander Pushkin, which satirizes Russia’s Europeanized aristocracy and is more of an introspection and psychological insight, drawing on the lyricism of the poem rather than theatrical effects an opera lends itself to. Tchaikovsky’s comment: “It is true that the work is deficient in theatrical opportunities; but the wealth of poetry, the humanity, and the simplicity of the story… will compensate for what is lacking in other respects.” [7] That is why he made Tatiana, not Onegin, the principal character, as that allowed him to develop the romantic aspect of the poem. Initially belittled as monotonous, it is now recognized as his operatic masterwork.

- The Maid of Orleans (Орлеанская дева – Orleanskaya deva) – 1878–1879

- Premiered in February 1881 in Saint Petersburg

- Mazeppa (Мазепа) – 1881–1883

- Premiered in February 1884 in Moscow

- Cherevichki (Черевички; revision of Vakula the Smith) – 1885

- Premiered in January 1887 in Moscow

- The Enchantress (also The Sorceress, Чародейка – Charodeyka) – 1885–1887

- Premiered in November 1887 in St Petersburg

- The Queen of Spades (Пиковая дама - Pikovaya dama), Op. 68 – 1890

- Premiered in December 1890 in St Petersburg

- Iolanthe (Иоланта – Iolanthe), Op. 69 – 1891

- First performed in Saint Petersburg in 1892.

- Planned opera Mandragora (Мандрагора), of which only a "Chorus of Insects" was composed in 1870

Symphonies

Tchaikovsky's earlier symphonies are generally optimistic works of a nationalist character; the latter are more dramatic, particularly The Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth, recognized for the uniqueness of their format. He also left behind four orchestral suites originally intended as a "symphony" but was persuaded to alter the title.

- Symphony No. 1 in G Minor, Op. 13, Winter Daydreams – 1866

- Symphony No. 2 in C Minor, Op. 17, Little Russian – 1872

- Symphony No. 3 in D Minor, Op. 29, Polish (for its use of polonaise) – 1875

- Symphony No. 4 in F Minor, Op. 36 – 1877–1878

- Conceived after he fled his wife and began friendship with von Meck. He dedicated it to von Meck, describing the symphony to her as “ours”, confessing “how much I thought of you with every bar.” [8]

- Manfred, Symphony in B Minor, Op. 58 – 1885

- Inspired by Byron's poem "Manfred"

- Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Op. 64 – 1888

- Written while haunted by fears of the work’s failure, having lost confidence in his musical prowess. The Fifth is interpreted as a story of the Fate and labeled by critics as his most unified symphony in purpose and design.

- Symphony No. 7: see below, Piano Concerto No. 3)

- Symphony No. 6 in B Minor, Op. 74, Pathétique – 1893

- Composed amidst the torment of depression; considered as the most pessimistic and dramatic of his pieces. He considered it the best and most sincere work he has written and was very satisfied and proud of it. Being the most tragic piece he ever wrote, originally it was to be entitled The Program Symphony, which was interpreted by some as an effort at his own requiem. He confessed that he repeatedly burst into tears when writing it. This is his greatest symphony and his most popular as well as the most celebrated symphony in Russian music and possibly in Romantic music.

Concerti

- Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-flat Minor, Op. 23 – 1874–1875

- One of the most popular piano concertos ever written, dedicated to the pianist Nikolai Grigoryevich Rubinstein. When he played it for Rubinstein in an empty classroom in the Conservatory, Rubinstein was silent, and when the performance ended, he told Tchaikovsky that it was worthless and unplayable for its commonplace passages that were beyond improvement, for its triviality and vulgarity, and for borrowing from other composers and sources. Tchaikovsky's response was, "I shall not change a single note, and I shall publish the concerto as it is now. And this, indeed, I did." [9] Hans von Bülow introduced it to the world in Boston, Massachusetts in 1875, with a phenomenal success. Rubinstein later admitted his error of judgment and included the work in his repertoire.

- Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 35 – 1878

- Composed in less than a month in 1878 but its first performance was delayed until 1881 because Leopold Auer, the violinist to whom Tchaikovsky had intended to dedicate it, refused to perform it for its technical difficulty. Austrian violinist Adolf Brodsky later played it to a public that was apathetic due to the violin’s out-of-fashion status. Presently one of the most popular concertos for the violin.

- Piano Concerto No. 2, Op. 44 – 1879

- Piano Concerto No. 3 – 1892

- Commenced after the Symphony No. 5, it was intended to be the next numbered symphony but he set it aside after nearly finishing the first movement. In 1893, after beginning work on Pathétique, he reworked the sketches of the first movement and completed the instrumentation to create a piece for piano and orchestra known as Allegro de concert or Konzertstück (published posthumously as Op. 75). Tchaikovsky also produced a piano arrangement of the slow movement (Andante) and last movement (Finale) of the symphony. He turned the scherzo into another piano piece, the Scherzo-fantasie in E-flat minor, Op. 72, No. 10. After his death, composer Sergei Taneyev completed and orchestrated the Andante and Finale, published as Op. 79. A reconstruction of the original symphony from the sketches and various revisions was accomplished during 1951–1955 by the Soviet composer Semyon Bogatyrev, who brought the symphony into finished, fully orchestrated form and issued the score as Symphony No 7 in E-flat major.[10]

For Orchestra

- Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture – 1869, revised in 1870 and 1880

- Written on suggestion from Balakirev. Balakirev was not satisfied with its first version and suggested numerous changes; after the revision, he declared that it was Tchaikovsky’s best work. Later on Tchaikovsky revised it again, which is the version enjoyed by modern audiences. Its melodies are used in movies and commercials.

- The Tempest "Symphonic Fantasia After Shakespeare,” Op. 18 – 1873

- Slavonic March (Marche Slave), Op. 31 – 1876

- Written for a beneficial concert for Serbian soldiers wounded in the war against Turkey, it expresses his sympathies for the Slavs and predicts their ultimate victory. The melody borrows from an old Serbian song and the Russian National Anthem. Commonly referenced in cartoons, commercials, and the media.

- Francesca da Rimini, Op. 32 – 1876

- The inspiration came from Dante Aligieri’s Inferno. He provided a program for it, explaining that the first section describes the gateway to the Inferno and the agonies suffered by those who reside there, while the middle part relates the tragic love story of Paolo and Francesca. The third part is a return to the Inferno.

- Capriccio Italien, Op. 45 – 1880

- A traditional caprice (capriccio) in an Italian style. Tchaikovsky stayed in Italy from the late 1870s to early 1880s and during the various festivals he heard many themes featured in the piece. It has a lighter character than many of his works, even "bouncy" in places, and is often performed today in addition to the 1812 Overture. The title is a linguistic hybrid: it contains an Italian word ("Capriccio") and a French word ("Italien"). A fully Italian version would be Capriccio Italiano; a fully French version would be Caprice Italien.

- Serenade in C for String Orchestra, Op. 48 – 1880

- The first movement, in the form of a sonatina, was a homage to Mozart. The second movement is a waltz, followed by an elegy and a spirited Russian finale, Tema Russo.

- 1812 Overture, Op. 49 – 1880

- Written reluctantly to commemorate the Russian victory over Napoleon in the Napoleonic Wars. Known for its traditional Russian themes, such as the old Tsarist National Anthem, as well as its triumphant and bombastic coda at the end, which makes use of 16 cannon shots and a chorus of church bells.

- Coronation March, Op. 50 – 1883

- The mayor of Moscow commissioned this piece for performance in May 1883 at the coronation of Alexander III.

- Mozartiana, op. 61 – 1887

- Devoted to the composer he admired above all ; adapts for orchestra some of Mozart’s less familiar compositions. He wished to revive the study of those “little masterworks, whose succinct form contains incomparable beauties.”[11]

For Orchestra, Choir and Vocal Soloists

- Snegurochka (The Snow Maiden) – 1873

- Incidental music for Alexander Ostrovsky's play of the same name.

For Orchestra, Soprano, and Baritone

- Hamlet – 1891

- Incidental music for Shakespeare's play.

For Choir, Songs, Chamber Music, and For Solo Piano and Violin

- String Quartet No. 1 in D Major, Op. 11 – 1871

- Variations on a Rococo Theme for Cello and Orchestra, Op. 33. – 1876

- Piano suite The Seasons, Op. 37a – 1876

- Three pieces: Meditation, Scherzo and Melody, Op. 42, for violin and piano

- Russian Vesper Service, Op. 52 – 1881

- Piano Trio in A minor, Op. 50 – 1882

- Commissioned by Madame von Meck as a chamber music work for her household trio, including pianist Claude Debussy. At the same time, it is an elegy on the death of Nikolai Rubinstein.

- Dumka, Russian rustic scene in C minor for piano, Op. 59 – 1886

- String sextet Souvenir de Florence, Op. 70 – 1890

For a complete list of works by opus number, see [1]. For more detail on dates of composition, see [2].

Media

|

See also

- Nadezhda von Meck

- Antonina Miliukova Tchaikovskaya

- Nikolai Grigoryevich Rubinstein

- Tchaikovsky International Competition

- Tchaikovsky Symphony Orchestra of Moscow Radio

- Category:Compositions by Pyotr Tchaikovsky

- Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians

Citations

- ↑ Ewen, 1966 p. 737 The Complete Book of Classical Music

- ↑ Ewen, 1966 p. 737-738 The Complete Book of Classical Music

- ↑ Ewen, 1966 p. 738 The Complete Book of Classical Music

- ↑ http://www.glbtq.com/arts/tchaikovsky_pi.html

- ↑ Ewen, 1966 p. 741 The Complete Book of Classical Music

- ↑ Ewen, 1966 p. 742 The Complete Book of Classical Music

- ↑ Ewen, 1966 p. 752 The Complete Book of Classical Music

- ↑ Ewen, 1966 p. 751 The Complete Book of Classical Music

- ↑ Ewen, 1966 p. 745 The Complete Book of Classical Music

- ↑ Wiley, Roland. 'Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Il′yich, §6(ii): Years of valediction, 1889–93: The last symphony'; Works: solo instrument and orchestra; Works: orchestral, Grove Music Online (Accessed 07 February 2006), <http://www.grovemusic.com> (subscription required). Brown, David. Tchaikovsky: the Final Years (1885-1893). New York: W.W. Norton, 1991, pp. 388-391, 497.

- ↑ Ewen, 1966 p. 759 The Complete Book of Classical Music

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Poznansky, Alexander & Langston, Brett The Tchaikovsky Handbook: A guide to the man and his music. (Indiana University Press, 2002) Vol. 1. Thematic Catalogue of Works, Catalogue of Photographs, Autobiography. 636 pages. ISBN 0-253-33921-9. Vol. 2. Catalogue of Letters, Genealogy, Bibliography. 832 pages. ISBN 0-253-33947-2.

- Greenberg, Robert "Great Masters: Tchaikovsky — His Life and Music"

- Holden, Anthony Tchaikovsky: : A Biography Random House; 1st U.S. ed edition (February 27, 1996) ISBN 0-679-42006-1

- Kamien, Roger. Music : An Appreciation. Mcgraw-Hill College; 3rd edition (August 1, 1997) ISBN 0-07-036521-0

- ed. John Knowles Paine, Theodore Thomas, and Karl Klauser (1891). Famous Composers and Their Works, J.B. Millet Company.

- Meck Galina Von, Tchaikovsky Ilyich Piotr, Young Percy M. Tchaikovsky Cooper Square Publishers; 1st Cooper Square Press ed edition (October, 2000) ISBN 0-8154-1087-5

- Meck, Nadezhda Von Tchaikovsky Peter Ilyich, To My Best Friend: Correspondence Between Tchaikovsky and Nadezhda Von Meck 1876-1878 Oxford University Press (January 1, 1993) ISBN 0-19-816158-1

- Poznansky, Alexander, Tchaikovsky's Last Days, Oxford University Press (1996), ISBN 0-19-816596-X

- Poznansky, Alexander Tchaikovsky: the Quest for the Inner Man Lime Tree (1993) ISBN 0-413-45721-4 (hb), ISBN 0-413-45731-1 (pb)

- Poznansky, Alexander. Tchaikovsky through others' eyes. (Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press, 1999). ISBN 0-253-35545-0.

- Tchaikovsky, Modest The Life And Letters Of Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky University Press of the Pacific (2004) ISBN 1-4102-1612-8

- Tchaikovsky's sacred works by Polyansky

- Biography of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts

External links

- Tchaikovsky research (active site)

- Tchaikovsky (inactive site)

- Tchaikovsky page (inactive site)

- PBS Great Performances biography of Tchaikovsky

- Tchaikovsky cylinder recordings, from the Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara Library.

Public Domain Sheet Music:

- IMSLP - International Music Score Library Project's Tchaikovsky page.

- Mutopia Project Tchaikovsky Sheet Music at Mutopia

- WIMA Tchaikovsky Sheet Music at Werner Icking Music Archive

| Romanticism | |

|---|---|

| Eighteenth century - Nineteenth century | |

| Romantic music: Beethoven - Berlioz - Brahms - Chopin - Grieg - Liszt - Puccini - Schumann - Tchaikovsky - The Five - Verdi - Wagner | |

| Romantic poetry: Blake - Burns - Byron - Coleridge - Goethe - Hölderlin - Hugo - Keats - Lamartine - Leopardi - Lermontov - Mickiewicz - Nerval - Novalis - Pushkin - Shelley - Słowacki - Wordsworth | |

| Visual art and architecture: Brullov - Constable - Corot - Delacroix - Friedrich - Géricault - Gothic Revival architecture - Goya - Hudson River school - Leutze - Nazarene movement - Palmer - Turner | |

| Romantic culture: Bohemianism - Romantic nationalism | |

| << Age of Enlightenment | Victorianism >> Realism >> |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.