Difference between revisions of "Ojibwa" - New World Encyclopedia

m (Robot: Remove claimed tag) |

(updated & fixed) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | |||

:'''''Chippewa''' redirects here'' | :'''''Chippewa''' redirects here'' | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{otheruses4|the native North American people|other uses of "Ojibwa," "Ojibway," or "Ojibwe"|Ojibway (disambiguation)}} |

| + | {{redirect|Chippewa}} | ||

| + | {{Infobox Ethnic group| | ||

|group=Ojibwa | |group=Ojibwa | ||

| − | |image=[[Image: | + | |image=[[Image:Anishinabe.svg|200px]]<br/> Crest of the Ojibwa people |

|poptime=175,000 | |poptime=175,000 | ||

|popplace=[[United States]], [[Canada]] | |popplace=[[United States]], [[Canada]] | ||

| Line 11: | Line 12: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | The '''Ojibwa | + | {{Commons|Category:Ojibwa}} |

| + | |||

| + | The '''Ojibwa''' or '''Chippewa''' (also '''Ojibwe''', '''Ojibway''', '''Chippeway''') is the largest group of [[Native Americans in the United States|Native Americans]]-[[First Nations]] north of [[Mexico]], including [[Métis people (Canada)|Métis]]. They are the third largest in the [[United States]], surpassed only by [[Cherokee]] and [[Navajo Nation|Navajo]]. They are equally divided between the United States and [[Canada]]. Because they were formerly located mainly around [[Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario|Sault Ste. Marie]], at the outlet of [[Lake Superior]], the [[French people|French]] referred to them as '''Saulteurs'''. Ojibwa who subsequently moved to the [[prairie provinces]] of Canada have retained the name [[Saulteaux]]. Ojibwa who were originally located about the [[Mississagi River]] and made their way to [[southern Ontario]] are known as the [[Mississaugas]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As a major component group of the [[Anishinaabe]] peoples—which includes the [[Algonquin]], [[Nipissing First Nation|Nipissing]], [[Oji-Cree]], [[Ottawa (tribe)|Odawa]] and the [[Potawatomi]]—the Ojibwe peoples number over 100,000 in the U.S., living in an area stretching across the north from [[Michigan]] to [[Montana]]. Another 76,000, in 125 bands, live in Canada, stretching from western [[Québec]] to eastern [[British Columbia]]. They are known for their [[birch bark]] [[canoe]]s, sacred [[birch bark scrolls]], the use of [[cowrie]] shells, [[wild rice]], copper points, and for their use of gun technology from the British to defeat and push back the [[Dakota]] nation of the [[Sioux]] (1745). The Ojibwe Nation was the first to set the agenda for signing more detailed treaties with Canada's leaders before many settlers were allowed too far west. The [[Midewiwin]] Society is well respected as the keeper of detailed and complex scrolls of events, history, songs, maps, memories, stories, geometry, and mathematics.[http://emuseum.mnsu.edu/history/mncultures/anishinabe.html] | ||

==Name== | ==Name== | ||

| − | The [[autonym]] for this group of | + | The [[Exonym and endonym|autonym]] for this group of Anishinaabeg is "''Ojibwe''" (plural: ''Ojibweg''). This name is commonly anglicized as "Ojibwa." The name "Chippewa" is an anglicized corruption of "Ojibwa." Although [[Ojibwa ethnonyms|many variations]] exist in literature, "Chippewa" is more common in the United States and "Ojibwa" predominates in Canada, but both terms do exist in both countries. The exact meaning of the name "Ojibwe" is not known; the most common explanations on the name derivations are: |

| + | * from ''ojiibwabwe'' (/o/ + /jiibw/ + /abwe/), meaning "those who cook\roast until it puckers," referring to their fire-curing of [[moccasin (footwear)|moccasin]] seams to make them water-proof<ref>[http://www.humiliationstudies.org/documents/DaffernMultilingualDictionary.pdf Multilingual Dictionary for Multifaith and Multicultural Mediation and Education]</ref>, though some sources instead say this was a method of torture the Ojibwe implemented upon their enemies.<ref>Warren, William W. (1885; reprint: 1984) ''History of the Ojibway People''. ISBN 087351162X.</ref> | ||

| + | * from ''ozhibii'iwe'' (/o/ + /zhibii'/ + /iwe/), meaning "those who keep records [of a Vision]," referring to their form of pictorial writing, and [[pictograph]]s used in [[Midewiwin]] rites<ref>[http://www.ereader.com/product/book/excerpt/23450?book=Books_and_Islands_in_Ojibwe_Country L. Erdrich, ''Books and Islands in Ojibwe Country'' (2003)]</ref> | ||

| + | * from ''ojiibwe'' (/o/ + /jiib/ + /we/), meaning "those who speak-stiffly"\"those who stammer," referring to how the Ojibwe sounded to the [[Cree]]<ref>Johnston, Basil. (2007) ''Anishinaubae Thesaurus'' ISBN-10: 0870137530</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | However, in many Ojibwa communities throughout Canada and the U.S., the more generalized name "''Anishinaabe(-g)''" is becoming more common. | ||

==Language== | ==Language== | ||

{{main|Anishinaabe language}} | {{main|Anishinaabe language}} | ||

| − | + | The Ojibwe language is known as ''Anishinaabemowin'' or ''Ojibwemowin'', and is still widely spoken. The language belongs to the [[Algonquian languages|Algonquian]] linguistic group, and is descended from [[Proto-Algonquian language|Proto-Algonquian]]. Its sister languages include [[Blackfoot]], [[Cheyenne]], [[Cree]], [[Fox (tribe)|Fox]], [[Menominee]], [[Potawatomi]], and [[Shawnee]]. ''Anishinaabemowin'' is frequently referred to as a "Central Algonquian" language; however, Central Algonquian is an areal grouping rather than a genetic one. ''Ojibwemowin'' is the fourth most spoken Native language in [[North America]] (after [[Navajo language|Navajo]], [[Cree language|Cree]], and [[Inuktitut language|Inuktitut]]). Many decades of [[Fur trade|fur trading]] with the French established the language as one of the key trade languages of the [[Great Lakes]] and the northern [[Great Plains]]. | |

| + | |||

| + | The Ojibwe presence was made highly visible among non-Native Americans and around the world by the popularity of the [[epic poem]] ''[[The Song of Hiawatha]]'', written by [[Henry Wadsworth Longfellow]] in 1855. The epic contains many [[toponym]]s that originate from Ojibwa words. | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | ===Pre-contact | + | ===Pre-contact=== |

| − | According to their tradition, and from recordings in [[birch bark scrolls]], many | + | According to their tradition, and from recordings in [[birch bark scrolls]], many Ojibwe came from the eastern areas of North America, or [[Turtle Island (North America)|Turtle Island]], and from along the east coast. They traded widely across the continent for thousands of years and knew of the canoe routes west and a land route to the west coast. According to the oral history, seven great ''miigis'' (radiant/iridescent) beings appeared to the peoples in the [[Abenaki|''Waabanakiing'']] (Land of the Dawn, i.e. Eastern Land) to teach the peoples of the [[midewiwin|''mide'' way]] of life. However, one of the seven great ''miigis'' beings was too spiritually powerful and killed the peoples in the ''Waabanakiing'' when the people were in its presence. The six great ''miigis'' beings remained to teach while the one returned into the ocean. The six great ''miigis'' beings then established ''doodem'' (clans) for the peoples in the east. Of these ''doodem'', the five original [[Anishinaabe]] ''doodem'' were the ''Wawaazisii'' ([[Brown bullhead|Bullhead]]), ''Baswenaazhi'' (Echo-maker, i.e., [[Crane (bird)|Crane]]), ''Aan'aawenh'' ([[Pintail]] Duck), ''Nooke'' (Tender, i.e., [[Bear]]) and ''Moozoonsii'' (Little [[Moose]]), then these six ''miigis'' beings returned into the ocean as well. If the seventh ''miigis'' being stayed, it would have established the [[Thunderbird (mythology)|Thunderbird]] ''doodem''. |

| − | + | At a later time, one of these ''miigis'' beings appeared in a vision to relate a prophecy. The prophecy stated that if more of the Anishinaabeg did not move further west, they would not be able to keep their traditional ways alive because of the many new settlements and European immigrants that would arrive soon in the east. Their migration path would be symbolized by a series of smaller Turtle Islands, which was confirmed with ''miigis'' shells (i.e., [[cowry]] shells). After receiving assurance from the their "Allied Brothers" (i.e., [[Mi'kmaq]]) and "Father" (i.e., [[Abnaki]]) of their safety in having many more of the Anishinaabeg move inland, they advanced along the [[St. Lawrence River]] to the [[Ottawa River]] to [[Lake Nipissing]], and then to the [[Great Lakes]]. First of these smaller Turtle Islands was ''Mooniyaa'', which ''Mooniyaang'' ([[Montreal, Quebec]]) now stands. The "second stopping place" was in the vicinity of the ''Wayaanag-gakaabikaa'' (Concave Waterfalls, i.e. [[Niagara Falls]]). At their "third stopping place" near the present-day city of [[Detroit, Michigan]], the Anishinaabeg divided into six divisions, of which the Ojibwa was one of these six. The first significant new Ojibwa culture-centre was their "fourth stopping place" on ''Manidoo Minising'' ([[Manitoulin Island]]). Their first new political-centre was referred as their "fifth stopping place," in their present country at ''Baawiting'' (Sault Ste. Marie). | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Continuing their westward expansion, the Ojibwa divided into the "northern branch" following the north shore of [[Lake Superior]], and "southern branch" following the south shore of the same lake. In their expansion westward, the "northern branch" divided into a "westerly group" and a "southerly group." The "southern branch" and the "southerly group" of the "northern branch" came together at their "sixth stopping place" on Spirit Island ({{coord|46|41|15|N|092|11|21|W|region:US}}) located in the [[Saint Louis River|St. Louis River]] estuary of [[Duluth, Minnesota|Duluth]]/[[Superior, Wisconsin|Superior]] region where the people were directed by the ''miigis'' being in a vision to go to the "place where there is food (i.e. [[wild rice]]) upon the waters." Their second major settlement, referred as their "seventh stopping place," was at Shaugawaumikong (or ''Zhaagawaamikong'', French, ''[[Chequamegon Bay|Chequamegon]]'') on the southern shore of Lake Superior, near the present [[La Pointe, Wisconsin|La Pointe]] near [[Bayfield, Wisconsin]]. The "westerly group" of the "northern branch" continued their westward expansion along the [[Rainy River]], [[Red River of the North]], and across the northern [[Great Plains]] until reaching the [[Pacific Northwest]]. Along their migration to the west they came across many ''miigis'', or cowry shells, as told in the prophecy. | |

| − | + | ===Post-contact with Europeans=== | |

| + | The first historical mention of the Ojibwe occurs in the [[Jesuit]] Relation of 1640. Through their friendship with the French traders, they were able to obtain guns and thus successfully end their hereditary wars with the Sioux and Fox on their west and south. The Sioux were driven out from the Upper [[Mississippi River|Mississippi]] region, and the Fox were forced down from northern [[Wisconsin]] and compelled to ally with the [[Sac (people)|Sauk]]. By the end of the 18th century, the Ojibwa were the nearly unchallenged owners of almost all of present-day Michigan, northern Wisconsin, and Minnesota, including most of the [[Red River of the North|Red River]] area, together with the entire northern shores of Lakes [[Lake Huron|Huron]] and Superior on the Canadian side and extending westward to the [[Turtle Mountain (plateau)|Turtle Mountains]] of [[North Dakota]], where they became known as the Plains Ojibwa or Saulteaux. | ||

| − | + | The Ojibwa were part of a long term alliance with the [[Ottawa (tribe)|Ottawa]] and [[Potawatomi]] peoples, called the [[Council of Three Fires]] and which fought with the [[Iroquois Confederacy]] and the Sioux. The Ojibwa expanded eastward, taking over the lands alongside the eastern shores of Lake Huron and [[Georgian Bay]]. The Ojibwa allied with the French in the [[French and Indian War]], and with the [[United Kingdom|British]] in the [[War of 1812]]. | |

| − | + | In the U.S., the government attempted to [[Indian removal|remove]] all the Ojibwa to Minnesota west of Mississippi River, culminating in the [[Sandy Lake Tragedy]] and several hundred deaths. Through the efforts of [[Kechewaishke|Chief Buffalo]] and popular opinion against Ojibwa removal, the bands east of the Mississippi were allowed to return to permanent reservations on ceded territory. A few families were removed to [[Kansas]] as part of the Potawatomi removal. | |

| − | + | In British North America, the cession of land by [[treaty]] or purchase was governed by the [[Royal Proclamation of 1763]], and subsequently most of the land in [[Upper Canada]] was ceded to [[Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland|Great Britain]]. Even with the [[Jay Treaty]] signed between the Great Britain and the United States, the newly formed United States did not fully uphold the treaty, causing illegal immigration into Ojibwa and other Native American lands, which culminated in the [[Northwest Indian War]]. Subsequently, much of the lands in [[Ohio]], [[Indiana]], Michigan, parts of [[Illinois]] and Wisconsin, and northern Minnesota and North Dakota were ceded to the United States. However, provisions were made in many of the land cession treaties to allow for continued hunting, fishing and gathering of natural resources by the Ojibwe even after the land sales. In northwestern Ontario, [[Manitoba]], [[Saskatchewan]], and [[Alberta]], the numbered treaties were signed. [[British Columbia]] had no signed treaties until the late 20th century, and most areas have no treaties yet. There are ongoing treaty land entitlements to settle and negotiate. The treaties are constantly being reinterpreted by the courts because many of them are vague and difficult to apply in modern times. However, the numbered treaties were some of the most detailed treaties signed for their time. The Ojibwa Nation set the agenda and negotiated the first numbered treaties before they would allow safe passage of many more settlers to the prairies. | |

| − | + | Often, earlier treaties were known as "Peace and Friendship Treaties" to establish community bonds between the Ojibwa and the European settlers. These earlier treaties established the groundwork for cooperative resource sharing between the Ojibwa and the settlers. However, later treaties involving land cessions were seen as territorial advantages for both the United States and Canada, but the land cession terms were often not fully understood by the Ojibwa because of the cultural differences in understanding of the land. For the governments of the US and Canada, land was considered a commodity of value that could be freely bought, owned and sold. For the Ojibwa, land was considered a fully-shared resource, along with air, water and sunlight; concept of land sales or exclusive ownership of land was a foreign concept not known to the Ojibwa at the time of the treaty councils. Consequently, today in both Canada and the US, legal arguments in treaty-rights and treaty interpretations often bring to light the differences in cultural understanding of these treaty terms in order to come to legal understanding of the treaty obligations.[http://atlas.nrcan.gc.ca/site/english/maps/historical/indiantreaties/historicaltreaties]. | |

| − | + | During [[Indian Removal]], US government attempted to relocate tribes from to west of the [[Mississippi River]] as the white pioneers colonized the areas. But in the late 19th century, the government instead moved the tribes onto [[Indian reservation|reservations]]. The government attempted to do this to the Anishinabe in the [[Keweenaw Peninsula]] in the [[Upper Peninsula of Michigan]]. | |

| − | The | + | ==Culture== |

| − | + | [[Image:Eastman Johnson - Ojibwe Wigwam at Grand Portage - ebj - fig 22 pg 41.jpg|thumb|200px|left|Details of ''Ojibwe Wigwam at Grand Portage'' by [[Eastman Johnson]] ]] | |

| − | The | + | The Ojibwa live in groups (otherwise known as "bands"). Most Ojibwa, except for the Plains bands, lived a sedentary lifestyle, engaging in [[fishing]], [[hunting]], the [[farming]] of [[maize]] and [[Squash (vegetable)|squash]], and the harvesting of Manoomin ([[wild rice]]). Their typical dwelling was the '''wiigiwaam''' ([[wigwam]]), built either as a '''waaginogaan''' (domed-lodge) or as a '''nasawa'ogaan''' (pointed-lodge), made of [[birch bark]], [[juniper]] bark and [[willow]] saplings. They also developed a form of pictorial writing used in religious rites of the [[Midewiwin]] and recorded on birch bark [[scroll]]s and possibly on rock. The many complex pictures on the sacred scrolls communicate a lot of historical, geometrical, and mathematical knowledge. Ceremonies also used the ''miigis'' shell (cowry shell), which is naturally found in far away coastal areas; this fact suggests that there was a vast trade network across the continent at some time. The use and trade of [[copper]] across the continent is also proof of a very large area of trading that took place thousands of years ago, as far back as the [[Hopewell culture]]. Certain types of rock used for spear and arrow heads were also traded over large distances. The use of [[petroforms]], [[petroglyphs]], and [[pictographs]] was common throughout their traditional territories. Petroforms and [[medicine wheels]] were a way to teach the important concepts of four directions, astronomical observations about the seasons, and as a memorizing tool for certain stories and beliefs. |

| − | |||

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | During the summer months, the people attend '''jiingotamog''' for the spiritual and '''niimi'idimaa''' for a social gathering ([[pow-wow]]s or "pau waus") at various reservations in the ''Anishinaabe-Aki'' (Anishinaabe Country). Many people still follow the traditional ways of harvesting [[wild rice]], picking berries, hunting, making medicines, and making [[maple sugar]]. Many of the Ojibwa take part in [[sun dance]] ceremonies across the continent. The sacred scrolls are kept hidden away until those that are worthy and respect them are given permission to see them and interpret them properly. | |

| − | The | + | The Ojibwa would bury their dead in a [[burial mound]]; many erect a ''jiibegamig'' or a "spirit-house" over each mound. Instead of a headstone with the deceased's name inscribed upon it, a traditional burial mound would typically have a wooden marker, inscribed with the deceased's ''doodem''. Because of the distinct features of these burials, Ojibwa graves have been often looted by grave robbers. In the United States, many Ojibwa communities safe-guard their burial mounds through the enforcement of the [[Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act]]. |

| − | + | The Ojibwa viewed the world in two genders: animate and inanimate, rather than male and female. As an animate a person could serve the society as a male-role or a female-role. [[John Tanner (narrator)|John Tanner]] and anthropologist Hermann Baumann have documented that Ojibwa peoples do not fall into the European ideas of gender and its gender-roles, called ''egwakwe'' (or Anglicised to "agokwa"). Though these ''egwakweg'' may contribute to their community in whatever way brings out their best character, sometimes these documented male-to-female [[transsexual]] [[Midewiwin|''Midew'']] among the Ojibwa were more readily noticed by the non-Anishinaabe documenters.<ref>Feinberg, Leslie: Transgender Warriors, page 40. Beacon Press, 1996.</ref> A well-known ''egwakwe'' warrior and guide in Minnesota history was ''[[Ozaawindib]]''. | |

| − | |||

| − | — | + | Several Ojibwa bands in the United States cooperate in the [[Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission]], which manages their treaty hunting and fishing rights in the Lake Superior-[[Lake Michigan]] areas. The commission follows the directives of U.S. agencies to run [[List of U.S. state and tribal wilderness areas|several wilderness areas]]. Some Minnesota Ojibwa tribal councils cooperate in the [[1854 Treaty Authority]], which manages their treaty hunting and fishing rights in the [[Arrowhead Region]]. In Michigan, the [http://www.1836CORA.org 1836 Chippewa-Ottawa Resource Authority] manages the hunting, fishing and gathering rights about Sault Ste. Marie, and the waters of Lake Michigan and Lake Huron. In Canada, the [http://www.treaty3.ca/adminoffice/natural-resources.php Grand Council of Treaty #3] manages the [[Treaty 3]] hunting and fishing rights around [[Lake of the Woods]]. |

| − | + | ===Kinship and clan system=== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | ===Kinship and | ||

{{main|Anishinaabe clan system}} | {{main|Anishinaabe clan system}} | ||

| + | Ojibwa understanding of kinship is complex, and includes not only the immediate family but also the extended family. It is considered a modified [[Iroquois kinship|bifurcate merging]] [[Kinship and descent|kinship system]]. As with any bifurcate merging kinship system, siblings generally share the same term with [[parallel cousin|parallel-cousin]]s, because they are all part of the same clan. But the modified system allows for younger siblings to share the same kinship term with younger cross-cousins. Complexity wanes further from the speaker's immediate generation, but some complexity is retained with female relatives. For example, ''ninooshenh'' is "my mother's sister" or "my father's sister-in-law"—i.e., my parallel-aunt—but also "my parent's female cross-cousin." Great-grandparents and older generations, as well as great-grandchildren and younger generations are collectively called ''aanikoobijigan''. This system of kinship speaks of the nature of the Anishinaabe's philosophy and lifestyle, that is of interconnectedness and balance between all living generations and all generations of the past and of the future. | ||

| − | + | The Ojibwe people were divided into a number of '''odoodeman''' (clans; singular: ''odoodem'') named primarily for animal [[totem]]s (pronounced ''[[doodem]]''). The five original totems were ''Wawaazisii'' ([[Brown bullhead|Bullhead]]), ''Baswenaazhi'' ("Echo-maker," i.e., [[Crane (bird)|Crane]]), ''Aan'aawenh'' ([[Pintail]] Duck), ''Nooke'' ("Tender," i.e., [[Bear]]) and ''Moozwaanowe'' ("Little" [[Moose]]-tail). The Crane totem was the most vocal among the Ojibwa, and the Bear was the largest—so large, in fact, that it was sub-divided into body parts such as the head, the ribs and the feet. | |

| − | |||

| − | The Ojibwe people were divided into a number of '''odoodeman''' (clans; singular: ''odoodem'') named primarily for animal [[totem]]s ( | ||

| − | Traditionally, each band had a self-regulating council consisting of leaders of the communities' clans or ''odoodeman'', with the band often identified by the principle ''doodem''. | + | Traditionally, each band had a self-regulating council consisting of leaders of the communities' clans or ''odoodeman'', with the band often identified by the principle ''doodem''. In meeting others, the traditional greeting among the Ojibwe peoples is "What is your ''doodem''?" ''(Aaniin odoodemaayan?)'' in order to establish a social conduct between the two meeting parties as family, friends or enemies. Today, the greeting has been shortened to "''Aaniin''." |

===Spiritual beliefs=== | ===Spiritual beliefs=== | ||

{{main|Anishinaabe traditional beliefs}} | {{main|Anishinaabe traditional beliefs}} | ||

| + | The Ojibwa have a number of spiritual beliefs passed down by [[oral tradition]] under the [[Midewiwin]] teachings. These include a [[Creation myth#Ojibwa|creation myth]] and a recounting of the origins of ceremonies and rituals. Spiritual beliefs and rituals were very important to the Ojibwa because spirits guided them through life. Birch bark scrolls and petroforms were used to pass along knowledge and information, as well as used for ceremonies. Pictographs were also used for ceremonies. The [[sweatlodge]] is still used during important ceremonies about the four directions and to pass along the oral history of the people. Teaching lodges are still common today to teach the next generations about the language and ancient ways of the past. These old ways, ideas, and teachings are still preserved today with these living ceremonies. | ||

| − | The | + | ===Popular culture=== |

| + | The legend of the Ojibwa "[[Wendigo]]," in which tribesmen identify with a cannibalistic monster and prey on their families, is a story with many meanings, one of them points to the consequences of greed and the destruction that results from it. It is mentioned in the fiction of [[Thomas Pynchon]]. In his story ''Of Father's and Sons'', [[Ernest Hemingway]] uses two Ojibway as secondary characters. | ||

| − | + | Novelist [[Louise Erdrich]] is Anishinabe and has written about characters from her culture in ''Tracks'', ''Love Medicine'', and ''The Bingo Palace.'' Medicine woman [[Keewaydinoquay Peschel]] has written books on ethnobotany and books for children. [[Winona LaDuke]] is a popular political and intellectual voice for the Anishinabe people. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Novelist [[Louise Erdrich]] is Anishinabe and has written about characters from her culture in ''Tracks'', ''Love Medicine'', and ''The Bingo | ||

Literary theorist and writer [[Gerald Vizenor]] has drawn extensively on Anishinabe philosophies of language. | Literary theorist and writer [[Gerald Vizenor]] has drawn extensively on Anishinabe philosophies of language. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Bands== |

| + | Warren, in his ''History of the Ojibway People'', records 10 major divisions of the Ojibwa in the United States, omitting the Ojibwa located in Michigan, western Minnesota and westward, and all of Canada; if major historical bands located in Michigan and Ontario are added, the count becomes 14: | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | These 10 major divisions and other major groups that Warren did not record developed into these Ojibwa Bands and First Nations of today. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | == Notable people == | |

| − | + | *[[Hanging Cloud|Ah-shah-way-gee-she-go-qua (''Aazhawigiizhigokwe''/Hanging Cloud)]] (Warrioress) | |

| − | + | *[[David W. Anderson|David Wayne "Famous Dave" Anderson]] (Business Entrepreneur) | |

| + | *[[Edward Benton Banai]] (Writer) | ||

| + | *[[Dennis Banks]] (Political Activist) | ||

| + | *[[James Bartleman]] (Diplomat, Author) | ||

| + | *[[Adam Beach]] (Actor, Writer) | ||

| + | *[[Jason Behr]] (Writer) | ||

| + | *[[Grey Owl|Archibald "Grey Owl" Belaney]] (Naturalist and Writer) - English, but presented himself an Ojibwa | ||

| + | *[[Clyde Bellecourt]] (Social Activist) | ||

| + | *[[Vernon Bellecourt]] (Social Activist) | ||

| + | *[[Chief Bender]] (Baseball player) | ||

| + | *[[Benjamin Chee Chee]] (Artist) | ||

| + | *[[Carl Beam]] (Artist) | ||

| + | *[[George Copway]] (Missionary and Writer) | ||

| + | *[[Eddy Cobiness]] (Artist) | ||

| + | *[[Patrick DesJarlait]] (Commercial Artist) | ||

| + | *[[Louise Erdrich]] (Writer) | ||

| + | *[[Bill Gardner (Untouchables)|William Gardner]] - one of the [[Untouchables (law enforcement)|Untouchables]] | ||

| + | *[[Gordon Henry Jr.]] (Writer) | ||

| + | *[[Drew Hayden Taylor]] (Playwright, Author and Journalist) | ||

| + | *[[Virgil Hill]] (Boxer) | ||

| + | *[[Basil Johnston]] (Historian and Cultural Essayist) | ||

| + | *[[Peter Jones (missionary)|Peter Jones]] (Missionary and Writer) | ||

| + | *[[Kechewaishke|Ke-che-waish-ke (''Gichi-Weshkiinh''/Buffalo)]] (Chief) | ||

| + | *[[Maude Kegg]] (Author, Cultural Embassidor) | ||

| + | *[[Winona LaDuke]] (Activist and Writer) | ||

| + | *[[Carole LaFavor]] (Writer, ) | ||

| + | *[[Joe Lumsden]] (Chairman, Sault Tribe of Chippewa Indians) | ||

| + | *[[Loma Lyns]] (Singer, Songwriter) | ||

| + | *[[Rod Michano]] (AIDS Activist/Educator) | ||

| + | *[[Norval Morrisseau]] (Artist) | ||

| + | *[[Ted Nolan]] (Hockeyplayer) | ||

| + | *[[Jim Northrup]] (Columnist) | ||

| + | *[[Yellow_Head_%28person%29#Yellow_Head.2C_the_berdache|O-zaw-wen-dib (''Ozaawindib''/Yellow Head)]] (Warrioress, Guide) | ||

| + | *[[Leonard Peltier]] (Political Activist, Prisoner) | ||

| + | *[[Pogonegishik|Po-go-ne-gi-shik (''Bagonegiizhig''/Hole in the Day)]] (Chief) | ||

| + | *[[Buffy Sainte-Marie]] (Singer) | ||

| + | *[[Keith Secola]] (Rock and Blues Singer) | ||

| + | *[[Chris Simon]] (Hockey player) | ||

| + | *[[Drew Hayden Taylor]] (Playwright, Humorist, Columnist) | ||

| + | *[[Roy Thomas]] (Artist) | ||

| + | *[[David Treuer]] (Writer) | ||

| + | *[[Shania Twain]] (Singer) - non-Ojibwa of [[Cree]] heritage adopted by her Ojibwa stepfather | ||

| + | *[[E. Donald Two-Rivers]] (Poet, Playwright) | ||

| + | *[[Gerald Vizenor]] (Writer) | ||

| + | *[[Wawatam]] (Chief) | ||

| + | *[[William Whipple Warren]] (Historian) | ||

| + | *Henry Boucha (Hockey Player) | ||

| + | *[[Arron Asham]] (Hockey player) | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==Gallery== | ||

| + | <gallery> | ||

| + | Image:A-na-cam-e-gish-ca.jpg|[[A-na-cam-e-gish-ca]] (''Aanakamigishkaa''/"[Traces of] Foot Prints [upon the Ground]"), Ojibwa chief, painted by [[Charles Bird King]] | ||

| + | Image:Aysh-ke-bah-ke-ko-zhay.jpg|Bust of [[Aysh-ke-bah-ke-ko-zhay]] (''Eshkibagikoonzhe'' or "Flat Mouth"), a Leech Lake Ojibwa chief | ||

| + | Image:Nanongabe.jpg|Chief [[Beautifying Bird]] (''Nenaa'angebi''), by Benjamin Armstrong, 1891 | ||

| + | Image:Be sheekee.jpg|Bust of [[Beshekee]], war chief, modeled 1855, carved 1856 | ||

| + | Image:Caa-tou-see.jpg|''Caa-tou-see'', an Ojibwa, painted by Charles Bird King | ||

| + | Image:Hangingcloud.jpg|[[Hanging Cloud]], a female Ojibwa warrior | ||

| + | Image:Jack-O-Pa.jpg|[[Jack-O-Pa]] (''Shák'pí''/"Six"), an Ojibwa/Dakota chief, painted by Charles Bird King | ||

| + | Image:Eastman_Johnson_-_Kay_be_sen_day_way_We_Win_-_ejb_-_fig_101_-_pg_225.jpg|''Kay be sen day way We Win'', by [[Eastman Johnson]], 1857 | ||

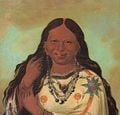

| + | Image:George Catlin 003.jpg|Kei-a-gis-gis, a Plains Ojibwa woman, painted by [[George Catlin]] | ||

| + | Image:Leech Lake Chippewa delegation to Washington 1899.png|Leech Lake Ojibwa delegation to Washington, 1899 | ||

| + | Image:23882 Ojibwe Woman1.jpg|[[Milwaukee]] Ojibwa woman and baby, courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society | ||

| + | Image:Ojibwa Chief.gif|[[Ne-bah-quah-om]], Ojibwa chief | ||

| + | Image:One-Called-From-A-Distance Chippewa.jpg|"One Called From A Distance" ''(Midwewinind)'' of the [[White Earth Band of Chippewa|White Earth Band]], 1894. | ||

| + | Image:PeeCheKir.jpg|[[Pee-Che-Kir]], Ojibwa chief, painted by [[Thomas Loraine McKenney]], 1843 | ||

| + | Image:Rocky Boy Chippewa chief.jpg|Ojibwa chief [[Rocky Boy]] | ||

| + | Image:Squawandchild.jpg|Ojibwa woman and child, painted by Charles Bird King | ||

| + | Image:Tshusick.jpg|''Tshusick'', an Ojibwa woman, painted by Charles Bird King | ||

| + | </gallery> | ||

| + | ==Notes== | ||

| + | <references /> | ||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | * F. Densmore, ''Chippewa Customs'' (1929, repr. 1970) | ||

| + | * H. Hickerson, ''The Chippewa and Their Neighbors'' (1970) | ||

| + | * [[Ruth Landes|R. Landes]], ''Ojibwa Sociology'' (1937, repr. 1969) | ||

| + | * R. Landes, ''Ojibwa Woman'' (1938, repr. 1971) | ||

| + | * F. Symington, ''The Canadian Indian'' (1969) | ||

| + | ==Further reading== | ||

| + | * Bento-Banai, Edward (2004). Creation- From the Ojibwa. The Mishomis Book. | ||

| + | * Danziger, E.J., Jr. (1978). ''The Chippewa of Lake Superior''. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. | ||

| + | * Densmore, F. (1979). ''Chippewa customs''. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press. (Ursprünglich 1929 veröffentlicht) | ||

| + | * Grim, J.A. (1983). ''The shaman: Patterns of religious healing among the Ojibway Indians''. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. | ||

| + | * Gross, L.W. (2002). ''The comic vision of Anishinaabe culture and religion''. American Indian Quarterly, 26, 436-459. | ||

| + | * Howse, Joseph. ''A Grammar of the Cree Language; With Which Is Combined an Analysis of the Chippeway Dialect''. London: J.G.F. & J. Rivington, 1844. | ||

| + | * Johnston, B. (1976). ''Ojibway heritage''. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart. | ||

| + | * Long, J. ''Voyages and Travels of an Indian Interpreter and Trader Describing the Manners and Customs of the North American Indians, with an Account of the Posts Situated on the River Saint Laurence, Lake Ontario, & C., to Which Is Added a Vocabulary of the Chippeway Language ... a List of Words in the Iroquois, Mehegan, Shawanee, and Esquimeaux Tongues, and a Table, Shewing the Analogy between the Algonkin and the Chippeway Languages''. London: Robson, 1791. | ||

| + | * Nichols, J.D., & Nyholm, E. (1995). ''A concise dictionary of Minnesota Ojibwe''. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. | ||

| + | * Vizenor, G. (1972). ''The everlasting sky: New voices from the people named the Chippewa''. New York: Crowell-Collier Press. | ||

| + | * Vizenor, G. (1981). ''Summer in the spring: Ojibwe lyric poems and tribal stories''. Minneapolis: The Nodin Press. | ||

| + | * Vizenor, G. (1984). ''The people named the Chippewa: Narrative histories''. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. | ||

| + | * Warren, William W. (1851). ''History of the Ojibway People.'' | ||

| + | * White, Richard (July 31, 2000). Chippewas of the Sault. The Sault Tribe News. | ||

| + | * Wub-e-ke-niew. (1995). ''We have the right to exist: A translation of aboriginal indigenous thought''. New York: Black Thistle Press. | ||

| + | ==External links== | ||

| + | * [http://www.glifwc.org/ Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission] | ||

| + | * [http://www.treatyland.com/ Midwest Treaty Network] | ||

| + | * [http://www.tolatsga.org/ojib.html Ojibwe culture and history], a lengthy and detailed discussion | ||

| + | * [http://www.freelang.net/dictionary/ojibwe.html Freelang Ojibwe Dictionary], an extensive electronic Ojibwe-English/English-Ojibwe language dictionary | ||

| + | * [http://www.geocities.com/Athens/Acropolis/5579/ojibwa.html Kevin L. Callahan's ''An Introduction to Ojibway Culture and History''] | ||

| + | * [http://www.ubu.com/ethno/visuals/chip.html Ojibwe Song Pictures], recorded by Frances Desmore | ||

| + | * [http://www.prairienet.org/prairienations/chippewa.htm Digital recreation of the 'Chippewa' entry] from ''Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico'', edited by Frederick Webb Hodge | ||

| + | * [http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/transactions/3/indianmigrations.shtml Ojibwa migration through Manitoba] | ||

| + | * [http://nativedrums.ca/index.php/video?tp=a&bg=1&ln=e video: The Making of an Ojibwe Hand Drum] | ||

| + | * [http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/wm/63.1/bohaker.html Nindoodemag: The Significance of Algonquian Kinship Networks in the Eastern Great Lakes Region, 1600–1701] | ||

| + | * [http://www.glifwc.org/pub/fall99/clansystem.htm Ojibwe clan systems: A cultural connection to the natural world] | ||

| + | * [http://www.aaronpayment.com/ Aaron Payment Tribal Chairman Sault Tribe Chippewas] | ||

| + | * [http://www.bemaadizing.org/ Bemaadizing: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Indigenous Life] (An online journal) | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{ | + | {{Credits|Ojibwa|248109913|}} |

Revision as of 18:50, 28 October 2008

- Chippewa redirects here

- This article is about the native North American people. For other uses of "Ojibwa," "Ojibway," or "Ojibwe", see Ojibway (disambiguation).

- "Chippewa" redirects here.

| Ojibwa |

|---|

Crest of the Ojibwa people |

| Total population |

| 175,000 |

| Regions with significant populations |

| United States, Canada |

| Languages |

| English, Ojibwe |

| Religions |

| Catholicism, Methodism, Midewiwin |

| Related ethnic groups |

| Ottawa, Potawatomi and other Algonquian peoples |

The Ojibwa or Chippewa (also Ojibwe, Ojibway, Chippeway) is the largest group of Native Americans-First Nations north of Mexico, including Métis. They are the third largest in the United States, surpassed only by Cherokee and Navajo. They are equally divided between the United States and Canada. Because they were formerly located mainly around Sault Ste. Marie, at the outlet of Lake Superior, the French referred to them as Saulteurs. Ojibwa who subsequently moved to the prairie provinces of Canada have retained the name Saulteaux. Ojibwa who were originally located about the Mississagi River and made their way to southern Ontario are known as the Mississaugas.

As a major component group of the Anishinaabe peoples—which includes the Algonquin, Nipissing, Oji-Cree, Odawa and the Potawatomi—the Ojibwe peoples number over 100,000 in the U.S., living in an area stretching across the north from Michigan to Montana. Another 76,000, in 125 bands, live in Canada, stretching from western Québec to eastern British Columbia. They are known for their birch bark canoes, sacred birch bark scrolls, the use of cowrie shells, wild rice, copper points, and for their use of gun technology from the British to defeat and push back the Dakota nation of the Sioux (1745). The Ojibwe Nation was the first to set the agenda for signing more detailed treaties with Canada's leaders before many settlers were allowed too far west. The Midewiwin Society is well respected as the keeper of detailed and complex scrolls of events, history, songs, maps, memories, stories, geometry, and mathematics.[1]

Name

The autonym for this group of Anishinaabeg is "Ojibwe" (plural: Ojibweg). This name is commonly anglicized as "Ojibwa." The name "Chippewa" is an anglicized corruption of "Ojibwa." Although many variations exist in literature, "Chippewa" is more common in the United States and "Ojibwa" predominates in Canada, but both terms do exist in both countries. The exact meaning of the name "Ojibwe" is not known; the most common explanations on the name derivations are:

- from ojiibwabwe (/o/ + /jiibw/ + /abwe/), meaning "those who cook\roast until it puckers," referring to their fire-curing of moccasin seams to make them water-proof[1], though some sources instead say this was a method of torture the Ojibwe implemented upon their enemies.[2]

- from ozhibii'iwe (/o/ + /zhibii'/ + /iwe/), meaning "those who keep records [of a Vision]," referring to their form of pictorial writing, and pictographs used in Midewiwin rites[3]

- from ojiibwe (/o/ + /jiib/ + /we/), meaning "those who speak-stiffly"\"those who stammer," referring to how the Ojibwe sounded to the Cree[4]

However, in many Ojibwa communities throughout Canada and the U.S., the more generalized name "Anishinaabe(-g)" is becoming more common.

Language

The Ojibwe language is known as Anishinaabemowin or Ojibwemowin, and is still widely spoken. The language belongs to the Algonquian linguistic group, and is descended from Proto-Algonquian. Its sister languages include Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Cree, Fox, Menominee, Potawatomi, and Shawnee. Anishinaabemowin is frequently referred to as a "Central Algonquian" language; however, Central Algonquian is an areal grouping rather than a genetic one. Ojibwemowin is the fourth most spoken Native language in North America (after Navajo, Cree, and Inuktitut). Many decades of fur trading with the French established the language as one of the key trade languages of the Great Lakes and the northern Great Plains.

The Ojibwe presence was made highly visible among non-Native Americans and around the world by the popularity of the epic poem The Song of Hiawatha, written by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in 1855. The epic contains many toponyms that originate from Ojibwa words.

History

Pre-contact

According to their tradition, and from recordings in birch bark scrolls, many Ojibwe came from the eastern areas of North America, or Turtle Island, and from along the east coast. They traded widely across the continent for thousands of years and knew of the canoe routes west and a land route to the west coast. According to the oral history, seven great miigis (radiant/iridescent) beings appeared to the peoples in the Waabanakiing (Land of the Dawn, i.e. Eastern Land) to teach the peoples of the mide way of life. However, one of the seven great miigis beings was too spiritually powerful and killed the peoples in the Waabanakiing when the people were in its presence. The six great miigis beings remained to teach while the one returned into the ocean. The six great miigis beings then established doodem (clans) for the peoples in the east. Of these doodem, the five original Anishinaabe doodem were the Wawaazisii (Bullhead), Baswenaazhi (Echo-maker, i.e., Crane), Aan'aawenh (Pintail Duck), Nooke (Tender, i.e., Bear) and Moozoonsii (Little Moose), then these six miigis beings returned into the ocean as well. If the seventh miigis being stayed, it would have established the Thunderbird doodem.

At a later time, one of these miigis beings appeared in a vision to relate a prophecy. The prophecy stated that if more of the Anishinaabeg did not move further west, they would not be able to keep their traditional ways alive because of the many new settlements and European immigrants that would arrive soon in the east. Their migration path would be symbolized by a series of smaller Turtle Islands, which was confirmed with miigis shells (i.e., cowry shells). After receiving assurance from the their "Allied Brothers" (i.e., Mi'kmaq) and "Father" (i.e., Abnaki) of their safety in having many more of the Anishinaabeg move inland, they advanced along the St. Lawrence River to the Ottawa River to Lake Nipissing, and then to the Great Lakes. First of these smaller Turtle Islands was Mooniyaa, which Mooniyaang (Montreal, Quebec) now stands. The "second stopping place" was in the vicinity of the Wayaanag-gakaabikaa (Concave Waterfalls, i.e. Niagara Falls). At their "third stopping place" near the present-day city of Detroit, Michigan, the Anishinaabeg divided into six divisions, of which the Ojibwa was one of these six. The first significant new Ojibwa culture-centre was their "fourth stopping place" on Manidoo Minising (Manitoulin Island). Their first new political-centre was referred as their "fifth stopping place," in their present country at Baawiting (Sault Ste. Marie).

Continuing their westward expansion, the Ojibwa divided into the "northern branch" following the north shore of Lake Superior, and "southern branch" following the south shore of the same lake. In their expansion westward, the "northern branch" divided into a "westerly group" and a "southerly group." The "southern branch" and the "southerly group" of the "northern branch" came together at their "sixth stopping place" on Spirit Island () located in the St. Louis River estuary of Duluth/Superior region where the people were directed by the miigis being in a vision to go to the "place where there is food (i.e. wild rice) upon the waters." Their second major settlement, referred as their "seventh stopping place," was at Shaugawaumikong (or Zhaagawaamikong, French, Chequamegon) on the southern shore of Lake Superior, near the present La Pointe near Bayfield, Wisconsin. The "westerly group" of the "northern branch" continued their westward expansion along the Rainy River, Red River of the North, and across the northern Great Plains until reaching the Pacific Northwest. Along their migration to the west they came across many miigis, or cowry shells, as told in the prophecy.

Post-contact with Europeans

The first historical mention of the Ojibwe occurs in the Jesuit Relation of 1640. Through their friendship with the French traders, they were able to obtain guns and thus successfully end their hereditary wars with the Sioux and Fox on their west and south. The Sioux were driven out from the Upper Mississippi region, and the Fox were forced down from northern Wisconsin and compelled to ally with the Sauk. By the end of the 18th century, the Ojibwa were the nearly unchallenged owners of almost all of present-day Michigan, northern Wisconsin, and Minnesota, including most of the Red River area, together with the entire northern shores of Lakes Huron and Superior on the Canadian side and extending westward to the Turtle Mountains of North Dakota, where they became known as the Plains Ojibwa or Saulteaux.

The Ojibwa were part of a long term alliance with the Ottawa and Potawatomi peoples, called the Council of Three Fires and which fought with the Iroquois Confederacy and the Sioux. The Ojibwa expanded eastward, taking over the lands alongside the eastern shores of Lake Huron and Georgian Bay. The Ojibwa allied with the French in the French and Indian War, and with the British in the War of 1812.

In the U.S., the government attempted to remove all the Ojibwa to Minnesota west of Mississippi River, culminating in the Sandy Lake Tragedy and several hundred deaths. Through the efforts of Chief Buffalo and popular opinion against Ojibwa removal, the bands east of the Mississippi were allowed to return to permanent reservations on ceded territory. A few families were removed to Kansas as part of the Potawatomi removal.

In British North America, the cession of land by treaty or purchase was governed by the Royal Proclamation of 1763, and subsequently most of the land in Upper Canada was ceded to Great Britain. Even with the Jay Treaty signed between the Great Britain and the United States, the newly formed United States did not fully uphold the treaty, causing illegal immigration into Ojibwa and other Native American lands, which culminated in the Northwest Indian War. Subsequently, much of the lands in Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, parts of Illinois and Wisconsin, and northern Minnesota and North Dakota were ceded to the United States. However, provisions were made in many of the land cession treaties to allow for continued hunting, fishing and gathering of natural resources by the Ojibwe even after the land sales. In northwestern Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta, the numbered treaties were signed. British Columbia had no signed treaties until the late 20th century, and most areas have no treaties yet. There are ongoing treaty land entitlements to settle and negotiate. The treaties are constantly being reinterpreted by the courts because many of them are vague and difficult to apply in modern times. However, the numbered treaties were some of the most detailed treaties signed for their time. The Ojibwa Nation set the agenda and negotiated the first numbered treaties before they would allow safe passage of many more settlers to the prairies.

Often, earlier treaties were known as "Peace and Friendship Treaties" to establish community bonds between the Ojibwa and the European settlers. These earlier treaties established the groundwork for cooperative resource sharing between the Ojibwa and the settlers. However, later treaties involving land cessions were seen as territorial advantages for both the United States and Canada, but the land cession terms were often not fully understood by the Ojibwa because of the cultural differences in understanding of the land. For the governments of the US and Canada, land was considered a commodity of value that could be freely bought, owned and sold. For the Ojibwa, land was considered a fully-shared resource, along with air, water and sunlight; concept of land sales or exclusive ownership of land was a foreign concept not known to the Ojibwa at the time of the treaty councils. Consequently, today in both Canada and the US, legal arguments in treaty-rights and treaty interpretations often bring to light the differences in cultural understanding of these treaty terms in order to come to legal understanding of the treaty obligations.[2].

During Indian Removal, US government attempted to relocate tribes from to west of the Mississippi River as the white pioneers colonized the areas. But in the late 19th century, the government instead moved the tribes onto reservations. The government attempted to do this to the Anishinabe in the Keweenaw Peninsula in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

Culture

The Ojibwa live in groups (otherwise known as "bands"). Most Ojibwa, except for the Plains bands, lived a sedentary lifestyle, engaging in fishing, hunting, the farming of maize and squash, and the harvesting of Manoomin (wild rice). Their typical dwelling was the wiigiwaam (wigwam), built either as a waaginogaan (domed-lodge) or as a nasawa'ogaan (pointed-lodge), made of birch bark, juniper bark and willow saplings. They also developed a form of pictorial writing used in religious rites of the Midewiwin and recorded on birch bark scrolls and possibly on rock. The many complex pictures on the sacred scrolls communicate a lot of historical, geometrical, and mathematical knowledge. Ceremonies also used the miigis shell (cowry shell), which is naturally found in far away coastal areas; this fact suggests that there was a vast trade network across the continent at some time. The use and trade of copper across the continent is also proof of a very large area of trading that took place thousands of years ago, as far back as the Hopewell culture. Certain types of rock used for spear and arrow heads were also traded over large distances. The use of petroforms, petroglyphs, and pictographs was common throughout their traditional territories. Petroforms and medicine wheels were a way to teach the important concepts of four directions, astronomical observations about the seasons, and as a memorizing tool for certain stories and beliefs.

During the summer months, the people attend jiingotamog for the spiritual and niimi'idimaa for a social gathering (pow-wows or "pau waus") at various reservations in the Anishinaabe-Aki (Anishinaabe Country). Many people still follow the traditional ways of harvesting wild rice, picking berries, hunting, making medicines, and making maple sugar. Many of the Ojibwa take part in sun dance ceremonies across the continent. The sacred scrolls are kept hidden away until those that are worthy and respect them are given permission to see them and interpret them properly.

The Ojibwa would bury their dead in a burial mound; many erect a jiibegamig or a "spirit-house" over each mound. Instead of a headstone with the deceased's name inscribed upon it, a traditional burial mound would typically have a wooden marker, inscribed with the deceased's doodem. Because of the distinct features of these burials, Ojibwa graves have been often looted by grave robbers. In the United States, many Ojibwa communities safe-guard their burial mounds through the enforcement of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

The Ojibwa viewed the world in two genders: animate and inanimate, rather than male and female. As an animate a person could serve the society as a male-role or a female-role. John Tanner and anthropologist Hermann Baumann have documented that Ojibwa peoples do not fall into the European ideas of gender and its gender-roles, called egwakwe (or Anglicised to "agokwa"). Though these egwakweg may contribute to their community in whatever way brings out their best character, sometimes these documented male-to-female transsexual Midew among the Ojibwa were more readily noticed by the non-Anishinaabe documenters.[5] A well-known egwakwe warrior and guide in Minnesota history was Ozaawindib.

Several Ojibwa bands in the United States cooperate in the Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission, which manages their treaty hunting and fishing rights in the Lake Superior-Lake Michigan areas. The commission follows the directives of U.S. agencies to run several wilderness areas. Some Minnesota Ojibwa tribal councils cooperate in the 1854 Treaty Authority, which manages their treaty hunting and fishing rights in the Arrowhead Region. In Michigan, the 1836 Chippewa-Ottawa Resource Authority manages the hunting, fishing and gathering rights about Sault Ste. Marie, and the waters of Lake Michigan and Lake Huron. In Canada, the Grand Council of Treaty #3 manages the Treaty 3 hunting and fishing rights around Lake of the Woods.

Kinship and clan system

Ojibwa understanding of kinship is complex, and includes not only the immediate family but also the extended family. It is considered a modified bifurcate merging kinship system. As with any bifurcate merging kinship system, siblings generally share the same term with parallel-cousins, because they are all part of the same clan. But the modified system allows for younger siblings to share the same kinship term with younger cross-cousins. Complexity wanes further from the speaker's immediate generation, but some complexity is retained with female relatives. For example, ninooshenh is "my mother's sister" or "my father's sister-in-law"—i.e., my parallel-aunt—but also "my parent's female cross-cousin." Great-grandparents and older generations, as well as great-grandchildren and younger generations are collectively called aanikoobijigan. This system of kinship speaks of the nature of the Anishinaabe's philosophy and lifestyle, that is of interconnectedness and balance between all living generations and all generations of the past and of the future.

The Ojibwe people were divided into a number of odoodeman (clans; singular: odoodem) named primarily for animal totems (pronounced doodem). The five original totems were Wawaazisii (Bullhead), Baswenaazhi ("Echo-maker," i.e., Crane), Aan'aawenh (Pintail Duck), Nooke ("Tender," i.e., Bear) and Moozwaanowe ("Little" Moose-tail). The Crane totem was the most vocal among the Ojibwa, and the Bear was the largest—so large, in fact, that it was sub-divided into body parts such as the head, the ribs and the feet.

Traditionally, each band had a self-regulating council consisting of leaders of the communities' clans or odoodeman, with the band often identified by the principle doodem. In meeting others, the traditional greeting among the Ojibwe peoples is "What is your doodem?" (Aaniin odoodemaayan?) in order to establish a social conduct between the two meeting parties as family, friends or enemies. Today, the greeting has been shortened to "Aaniin."

Spiritual beliefs

The Ojibwa have a number of spiritual beliefs passed down by oral tradition under the Midewiwin teachings. These include a creation myth and a recounting of the origins of ceremonies and rituals. Spiritual beliefs and rituals were very important to the Ojibwa because spirits guided them through life. Birch bark scrolls and petroforms were used to pass along knowledge and information, as well as used for ceremonies. Pictographs were also used for ceremonies. The sweatlodge is still used during important ceremonies about the four directions and to pass along the oral history of the people. Teaching lodges are still common today to teach the next generations about the language and ancient ways of the past. These old ways, ideas, and teachings are still preserved today with these living ceremonies.

Popular culture

The legend of the Ojibwa "Wendigo," in which tribesmen identify with a cannibalistic monster and prey on their families, is a story with many meanings, one of them points to the consequences of greed and the destruction that results from it. It is mentioned in the fiction of Thomas Pynchon. In his story Of Father's and Sons, Ernest Hemingway uses two Ojibway as secondary characters.

Novelist Louise Erdrich is Anishinabe and has written about characters from her culture in Tracks, Love Medicine, and The Bingo Palace. Medicine woman Keewaydinoquay Peschel has written books on ethnobotany and books for children. Winona LaDuke is a popular political and intellectual voice for the Anishinabe people.

Literary theorist and writer Gerald Vizenor has drawn extensively on Anishinabe philosophies of language.

Bands

Warren, in his History of the Ojibway People, records 10 major divisions of the Ojibwa in the United States, omitting the Ojibwa located in Michigan, western Minnesota and westward, and all of Canada; if major historical bands located in Michigan and Ontario are added, the count becomes 14:

These 10 major divisions and other major groups that Warren did not record developed into these Ojibwa Bands and First Nations of today.

Notable people

- Ah-shah-way-gee-she-go-qua (Aazhawigiizhigokwe/Hanging Cloud) (Warrioress)

- David Wayne "Famous Dave" Anderson (Business Entrepreneur)

- Edward Benton Banai (Writer)

- Dennis Banks (Political Activist)

- James Bartleman (Diplomat, Author)

- Adam Beach (Actor, Writer)

- Jason Behr (Writer)

- Archibald "Grey Owl" Belaney (Naturalist and Writer) - English, but presented himself an Ojibwa

- Clyde Bellecourt (Social Activist)

- Vernon Bellecourt (Social Activist)

- Chief Bender (Baseball player)

- Benjamin Chee Chee (Artist)

- Carl Beam (Artist)

- George Copway (Missionary and Writer)

- Eddy Cobiness (Artist)

- Patrick DesJarlait (Commercial Artist)

- Louise Erdrich (Writer)

- William Gardner - one of the Untouchables

- Gordon Henry Jr. (Writer)

- Drew Hayden Taylor (Playwright, Author and Journalist)

- Virgil Hill (Boxer)

- Basil Johnston (Historian and Cultural Essayist)

- Peter Jones (Missionary and Writer)

- Ke-che-waish-ke (Gichi-Weshkiinh/Buffalo) (Chief)

- Maude Kegg (Author, Cultural Embassidor)

- Winona LaDuke (Activist and Writer)

- Carole LaFavor (Writer, )

- Joe Lumsden (Chairman, Sault Tribe of Chippewa Indians)

- Loma Lyns (Singer, Songwriter)

- Rod Michano (AIDS Activist/Educator)

- Norval Morrisseau (Artist)

- Ted Nolan (Hockeyplayer)

- Jim Northrup (Columnist)

- O-zaw-wen-dib (Ozaawindib/Yellow Head) (Warrioress, Guide)

- Leonard Peltier (Political Activist, Prisoner)

- Po-go-ne-gi-shik (Bagonegiizhig/Hole in the Day) (Chief)

- Buffy Sainte-Marie (Singer)

- Keith Secola (Rock and Blues Singer)

- Chris Simon (Hockey player)

- Drew Hayden Taylor (Playwright, Humorist, Columnist)

- Roy Thomas (Artist)

- David Treuer (Writer)

- Shania Twain (Singer) - non-Ojibwa of Cree heritage adopted by her Ojibwa stepfather

- E. Donald Two-Rivers (Poet, Playwright)

- Gerald Vizenor (Writer)

- Wawatam (Chief)

- William Whipple Warren (Historian)

- Henry Boucha (Hockey Player)

- Arron Asham (Hockey player)

Gallery

- Aysh-ke-bah-ke-ko-zhay.jpg

Bust of Aysh-ke-bah-ke-ko-zhay (Eshkibagikoonzhe or "Flat Mouth"), a Leech Lake Ojibwa chief

- Nanongabe.jpg

Chief Beautifying Bird (Nenaa'angebi), by Benjamin Armstrong, 1891

- Be sheekee.jpg

Bust of Beshekee, war chief, modeled 1855, carved 1856

- Squawandchild.jpg

Ojibwa woman and child, painted by Charles Bird King

- Tshusick.jpg

Tshusick, an Ojibwa woman, painted by Charles Bird King

Notes

- ↑ Multilingual Dictionary for Multifaith and Multicultural Mediation and Education

- ↑ Warren, William W. (1885; reprint: 1984) History of the Ojibway People. ISBN 087351162X.

- ↑ L. Erdrich, Books and Islands in Ojibwe Country (2003)

- ↑ Johnston, Basil. (2007) Anishinaubae Thesaurus ISBN-10: 0870137530

- ↑ Feinberg, Leslie: Transgender Warriors, page 40. Beacon Press, 1996.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- F. Densmore, Chippewa Customs (1929, repr. 1970)

- H. Hickerson, The Chippewa and Their Neighbors (1970)

- R. Landes, Ojibwa Sociology (1937, repr. 1969)

- R. Landes, Ojibwa Woman (1938, repr. 1971)

- F. Symington, The Canadian Indian (1969)

Further reading

- Bento-Banai, Edward (2004). Creation- From the Ojibwa. The Mishomis Book.

- Danziger, E.J., Jr. (1978). The Chippewa of Lake Superior. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Densmore, F. (1979). Chippewa customs. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press. (Ursprünglich 1929 veröffentlicht)

- Grim, J.A. (1983). The shaman: Patterns of religious healing among the Ojibway Indians. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Gross, L.W. (2002). The comic vision of Anishinaabe culture and religion. American Indian Quarterly, 26, 436-459.

- Howse, Joseph. A Grammar of the Cree Language; With Which Is Combined an Analysis of the Chippeway Dialect. London: J.G.F. & J. Rivington, 1844.

- Johnston, B. (1976). Ojibway heritage. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart.

- Long, J. Voyages and Travels of an Indian Interpreter and Trader Describing the Manners and Customs of the North American Indians, with an Account of the Posts Situated on the River Saint Laurence, Lake Ontario, & C., to Which Is Added a Vocabulary of the Chippeway Language ... a List of Words in the Iroquois, Mehegan, Shawanee, and Esquimeaux Tongues, and a Table, Shewing the Analogy between the Algonkin and the Chippeway Languages. London: Robson, 1791.

- Nichols, J.D., & Nyholm, E. (1995). A concise dictionary of Minnesota Ojibwe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Vizenor, G. (1972). The everlasting sky: New voices from the people named the Chippewa. New York: Crowell-Collier Press.

- Vizenor, G. (1981). Summer in the spring: Ojibwe lyric poems and tribal stories. Minneapolis: The Nodin Press.

- Vizenor, G. (1984). The people named the Chippewa: Narrative histories. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Warren, William W. (1851). History of the Ojibway People.

- White, Richard (July 31, 2000). Chippewas of the Sault. The Sault Tribe News.

- Wub-e-ke-niew. (1995). We have the right to exist: A translation of aboriginal indigenous thought. New York: Black Thistle Press.

External links

- Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission

- Midwest Treaty Network

- Ojibwe culture and history, a lengthy and detailed discussion

- Freelang Ojibwe Dictionary, an extensive electronic Ojibwe-English/English-Ojibwe language dictionary

- Kevin L. Callahan's An Introduction to Ojibway Culture and History

- Ojibwe Song Pictures, recorded by Frances Desmore

- Digital recreation of the 'Chippewa' entry from Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, edited by Frederick Webb Hodge

- Ojibwa migration through Manitoba

- video: The Making of an Ojibwe Hand Drum

- Nindoodemag: The Significance of Algonquian Kinship Networks in the Eastern Great Lakes Region, 1600–1701

- Ojibwe clan systems: A cultural connection to the natural world

- Aaron Payment Tribal Chairman Sault Tribe Chippewas

- Bemaadizing: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Indigenous Life (An online journal)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.