Chukovsky, Korney

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (14 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{copyedited}} |

| + | {{epname|Chukovsky, Korney}} | ||

{{Infobox Writer | {{Infobox Writer | ||

| name = Korney Chukovsky | | name = Korney Chukovsky | ||

| Line 25: | Line 26: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | '''Korney Ivanovich Chukovsky''' ({{lang-ru|Корней Иванович Чуковский}}, March 31 | + | '''Korney Ivanovich Chukovsky''' ({{lang-ru|Корней Иванович Чуковский}}, March 31, 1882 - October 28, 1969) was one of the most popular children's [[poet]]s in the [[Russian language]]. His poems, "[[Doctor Aybolit]]" (Айболит), ''The Giant Roach'' (Тараканище), ''The Crocodile'' (Крокодил), and ''[[Moidodyr|Wash'em'clean]]'' (Мойдодыр) have been favorites with many generations of [[Russophone]] children. He also was an influential [[Literary criticism|literary critic]] and [[essay|essayist]]. |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| + | Chukovsky survived the imposition of [[Socialist realism]] at the 1934 Writers' Congress and the [[Stalinism|Stalinization]] of literary and cultural life. Later, after the end of the [[Krushchev Thaw]] and [[Leonid Brezhnev|Brezhnev]] retrenchment, Chukovsky worked on behalf of some of the writers who were attacked by the government. He joined [[Andrei Sakharov]] and others in signing a letter on the behalf of [[Andrei Sinyavsky]] and [[Yuli Daniel]] after their arrest and conviction. | ||

==Early life== | ==Early life== | ||

| + | Nikolay Vasilyevich Korneychukov (Russian: Николай Васильевич Корнейчуков) was born in [[Saint Petersburg|St. Petersburg]]. He reworked his original name into his now familiar pen-name while working as a journalist at ''[[Odessa]] News'' in 1901. Chukovksy was the illegitimate son of Ekaterina Osipovna Korneychukova, a peasant girl from the [[Poltava]] region of [[Ukraine]], and Emmanuil Solomonovich Levinson, a man from a wealthy Jewish family. (His legitimate grandson was mathematician [[Vladimir Abramovich Rokhlin]]). Levinson's family did not permit his marriage to Korneychukova, and they eventually separated. Korneychukova moved to Odessa with Nikolay and his sibling. Levinson supported them financially for some time until his marriage to another woman. Nikolay studied at the Odessa [[Gymnasium (school)|gymnasium]], where one of his classmates was Vladimir [[Zeev Jabotinsky]]. Later, Nikolay was expelled from the gymnasium for his "low origin" (an euphemism for illegitimacy). He had to get his [[secondary school]] and [[university]] diplomas by correspondence. | ||

| − | + | He taught himself English, and, in 1903-05, he served as the [[London]] [[correspondent]] at an Odessa newspaper, although he spent most of his time at the British Library instead of the press gallery in the Parliament. Back in [[Russia]], Chukovsky started translating English works, notably [[Walt Whitman]], and published several analyses of contemporary European authors, which brought him in touch with leading personalities of [[Russian literature]] and secured the friendship of noted [[Russian Symbolism|Symbolist]] poet,[[Alexander Blok]]. His influence on Russian literary society of the 1890s is immortalized by satirical verses of [[Sasha Cherny]], including ''Korney Belinsky'' (an allusion to the famous nineteenth century literary and social critic, [[Vissarion Belinsky]]). Later, he published several notable literary titles including ''From Chekhov to Our Days'' (1908), ''Critique Stories'' (1911), and ''Faces and Masks'' (1914). He also published a satirical magazine called ''Signal'' (1905-1906) and was arrested for "insulting the ruling house," but was acquitted after six months. | |

| − | |||

| − | He taught himself English, and, in 1903-05, he served as the [[London]] [[correspondent]] at an Odessa newspaper, although he spent most of his time at the British Library instead of the press gallery in the Parliament. Back in [[Russia]], Chukovsky started translating English works, notably [[Walt Whitman]], and published several analyses of contemporary European authors, which brought him in touch with leading personalities of [[Russian literature]] and secured the friendship of noted [[Russian Symbolism|Symbolist]] poet,[[Alexander Blok]]. His influence on Russian literary society of the 1890s is immortalized by satirical verses of [[Sasha Cherny]], including ''Korney Belinsky'' (an allusion to the famous | ||

==Later life== | ==Later life== | ||

| − | |||

[[Image:Mayakovsky Chukovsky.GIF|frame|[[Vladimir Mayakovsky|Mayakovsky]]'s caricature of Korney Chukovsky]] | [[Image:Mayakovsky Chukovsky.GIF|frame|[[Vladimir Mayakovsky|Mayakovsky]]'s caricature of Korney Chukovsky]] | ||

| − | It was during that period that Chukovsky produced his first fantasies for children. Chukovsky's verses helped to revolutionize the way that children's poetry was written; "their clockwork rhythms and air of mischief and lightness in effect dispelled the plodding stodginess that had characterized pre-revolutionary children's poetry." | + | It was during that period that Chukovsky produced his first fantasies for children. Chukovsky's verses helped to revolutionize the way that children's poetry was written; "their clockwork rhythms and air of mischief and lightness in effect dispelled the plodding stodginess that had characterized pre-revolutionary children's poetry." Subsequently, they were adapted for theater and [[animation|animated films]], with Chukovsky as one of the collaborators. [[Sergei Prokofiev]] and other composers even adapted some of his poems for [[opera]] and [[ballet]]. His works were popular with emigre children as well, as [[Vladimir Nabokov]]'s complimentary letter to Chukovsky attests. |

[[Image:Pastchuk.jpg|thumb|left|275px|[[Boris Pasternak]] (L) and Korney Chukovsky at the first Congress of the [[Union of Soviet Writers]] in 1934.]] | [[Image:Pastchuk.jpg|thumb|left|275px|[[Boris Pasternak]] (L) and Korney Chukovsky at the first Congress of the [[Union of Soviet Writers]] in 1934.]] | ||

| − | In addition to his children's verses, Chukovsky was an important critic, translator and editor. During the [[Soviet Union|Soviet period]], Chukovsky edited the complete works of | + | In addition to his children's verses, Chukovsky was an important critic, translator and editor. During the [[Soviet Union|Soviet period]], Chukovsky edited the complete works of nineteenth century poet and journalist, [[Nikolay Nekrasov]], who together with Belinski edited ''Sovremennik''. He also published ''From Two to Five'' (1933), (first published under the title ''Small Children''), a popular guidebook to the language of children. It was translated into many languages and printed in numerous editions. Chukovsky was also a member of the group of writers associated with the movement known as ''Factography''. |

===Factography=== | ===Factography=== | ||

| − | Factography was associated with the ''Left Front of the Arts'' ( | + | Factography was associated with the ''Left Front of the Arts'' (''Levyi Front Iskusstv''--''Левый фронт искусств''), a widely ranging association of avant-garde writers, photographers, critics and designers in the [[Soviet Union]], and their journal, ''LEF'' (''ЛЕФ''). It had two runs, one from 1923 to 1925, as LEF, and later from 1927 to 1929, as ''Novyi LEF'' (''New LEF''). The journal's objective, as set out in one of its first issues, was to "re-examine the ideology and practices of so-called leftist art, and to abandon individualism to increase art's value for developing [[communism]]." |

| − | The later New LEF, which was edited by Mayakovsky along with the playwright, screenplay writer and photographer [[Sergei Tretyakov]], tried to popularize the idea of | + | The later New LEF, which was edited by Mayakovsky along with the playwright, screenplay writer and photographer [[Sergei Tretyakov]], tried to popularize the idea of "Factography:" The idea that new technologies such as photography and film should be utilized by the working class for the production of "factographic" works. Chukovsky was one of its practitioners, along with [[Russian Formalism|Formalist]] critics [[Viktor Shklovsky]] and [[Yuri Tynyanov]] and poets [[Boris Pasternak]], [[Vladimir Mayakovsky]], and [[Osip Mandelshtam]]. |

Starting in the 1930s, Chukovsky lived in the writers' village of [[Peredelkino]] near [[Moscow]], where he is now buried. | Starting in the 1930s, Chukovsky lived in the writers' village of [[Peredelkino]] near [[Moscow]], where he is now buried. | ||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

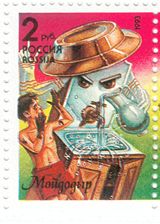

Moidodyr (1923) is a poem for children by [[Korney Chukovsky]] about a magical creature by the same name. The name may be translated as "Wash'em'clean." | Moidodyr (1923) is a poem for children by [[Korney Chukovsky]] about a magical creature by the same name. The name may be translated as "Wash'em'clean." | ||

| − | The poem is about a small boy who does not want to wash. He gets so dirty that all his toys, clothes and other possessions decide to magically leave him. Suddenly, from the boy's mother's bedroom appears Moidodyr - an anthropomorphic washstand. He claims to have powers over all washstands, soap bars and sponges. He scolds the boy and calls his soap bars and sponges to wash him. The boy tries to run away, chased by a vicious sponge. The chase is described as happening on [[St. Petersburg]] streets. Finally they meet another recurring character from Chukovsky's books - the Crocodile. The Crocodile swallows the sponge and becomes angry with the boy for being so dirty. Scared by the Crocodile, the boy goes back to Moidodyr and takes a bath. The poem ends with a moralistic note to children on the virtue of [[hygiene]]. | + | The poem is about a small boy who does not want to wash. He gets so dirty that all his toys, clothes and other possessions decide to magically leave him. Suddenly, from the boy's mother's bedroom appears Moidodyr--an anthropomorphic washstand. He claims to have powers over all washstands, soap bars and sponges. He scolds the boy and calls his soap bars and sponges to wash him. The boy tries to run away, chased by a vicious sponge. The chase is described as happening on [[St. Petersburg]] streets. Finally they meet another recurring character from Chukovsky's books--the Crocodile. The Crocodile swallows the sponge and becomes angry with the boy for being so dirty. Scared by the Crocodile, the boy goes back to Moidodyr and takes a bath. The poem ends with a moralistic note to children on the virtue of [[hygiene]]. |

Moidodyr character became a symbol of clearness in Russia and is often used to advertise detergents and other products. | Moidodyr character became a symbol of clearness in Russia and is often used to advertise detergents and other products. | ||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

Doctor Aybolit (Russian: Доктор Айболит, ''Aibolit'') is a [[fictional character]] from the ''Aybolit'' ''(Doctor Aybolit)'' poem for children by [[Korney Chukovsky]], that was followed by several more books by the same author. The name may be translated as "Ow, it hurts!" | Doctor Aybolit (Russian: Доктор Айболит, ''Aibolit'') is a [[fictional character]] from the ''Aybolit'' ''(Doctor Aybolit)'' poem for children by [[Korney Chukovsky]], that was followed by several more books by the same author. The name may be translated as "Ow, it hurts!" | ||

| − | The origins of ''Aybolit'' can be traced to [[Doctor Dolittle]] by [[Hugh Lofting]]. Like [[Buratino]] by Aleksey Tolstoy or [[The Wizard of the Emerald City]] by Alexander Volkov, ''Aybolit'' is a loose adaptation of a foreign book by a Russian author. For example, the adaptation includes a [[Pushmi-pullyu]], {{lang|ru|тяни-толкай}} (tyani-tolkay) in Russian. | + | The origins of ''Aybolit'' can be traced to ''[[Doctor Dolittle]]'' by [[Hugh Lofting]]. Like ''[[Buratino]]'' by Aleksey Tolstoy or ''[[The Wizard of the Emerald City]]'' by Alexander Volkov, ''Aybolit'' is a loose adaptation of a foreign book by a Russian author. For example, the adaptation includes a [[Pushmi-pullyu]], {{lang|ru|тяни-толкай}} (tyani-tolkay) in Russian. |

| − | A living prototype of the character may have been Chukovskys acquaintance, Vilnian [[Ashkenazi Jews|Jewish]] doctor Zemach Shabad (1864-1935), to whom a monument was uncovered in [[Vilnius]] on | + | A living prototype of the character may have been Chukovskys acquaintance, Vilnian [[Ashkenazi Jews|Jewish]] doctor Zemach Shabad (1864-1935), to whom a monument was uncovered in [[Vilnius]] on May 16, 2007. |

| − | The character has become a recognizable feature of [[Russian culture]]. There are films based on Doctor Aybolit (''Doktor Aybolit'' (black and white, 1938), ''[[Aybolit 66]]'' ([[Mosfilm]], 1967, English title: ''Oh How It Hurts 66''), ''Doctor Aybolit'' ([[animated film]], [[Kievnauchfilm]], 1985)). His appearance and name are used in names, logos, and slogans of various medical establishments, candies, | + | The character has become a recognizable feature of [[Russian culture]]. There are films based on Doctor Aybolit (''Doktor Aybolit'' (black and white, 1938), ''[[Aybolit 66]]'' ([[Mosfilm]], 1967, English title: ''Oh How It Hurts 66''), ''Doctor Aybolit'' ([[animated film]], ''[[Kievnauchfilm]],'' 1985)). His appearance and name are used in names, logos, and slogans of various medical establishments, candies, and so on. |

Aybolit's antagonist, an evil robber Barmaley, became an archetypal [[villain]] in Russian culture. Actually, Barmaley debuted in Chukovsky's book ''Crocodile'' in 1916, 13 years before the first appearance of Aybolit. | Aybolit's antagonist, an evil robber Barmaley, became an archetypal [[villain]] in Russian culture. Actually, Barmaley debuted in Chukovsky's book ''Crocodile'' in 1916, 13 years before the first appearance of Aybolit. | ||

| − | The poem is a source a number of Russian [[catch phrase]]s, such as "Nu spasibo tebe, Aybolit" | + | The poem is a source a number of Russian [[catch phrase]]s, such as "Nu spasibo tebe, Aybolit" ("Thanks to you, Aybolit"), "Ne hodite deti v Afriku gulyat" ("Children, don't go to Africa for a walk"). It was also the inspiration for the [[Barmaley Fountain]] in [[Stalingrad]]. |

==Legacy== | ==Legacy== | ||

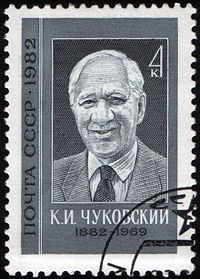

| + | [[Image:USSR stamp K.Chukovsky 1982 4k.jpg|thumb|right|200px|A [[USSR|Soviet]] [[Stamp]] commemorating Korney Chukovsky, 1982 (Michel 5164, Scott 5033)]] | ||

As his invaluable diaries attest, Chukovsky used his popularity to help the authors persecuted by the regime including [[Anna Akhmatova]], [[Mikhail Zoshchenko]], [[Alexander Galich]], and [[Alexander Solzhenitsyn|Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn]]. He was the only Soviet writer who officially congratulated [[Boris Pasternak]] on his having been awarded the [[Nobel Prize]] for [[literature]]. His daughter, [[Lydia Chukovskaya]], is remembered as a lifelong companion and secretary of the poet Anna Akhmatova, as well as an important writer herself. Chukovskaya's ''Sofia Petrovna'' was a courageous novella that was critical of the [[Stalinism|Stalinist]] [[Great Purges]], written during the time of [[Joseph Stalin|Stalin]]. | As his invaluable diaries attest, Chukovsky used his popularity to help the authors persecuted by the regime including [[Anna Akhmatova]], [[Mikhail Zoshchenko]], [[Alexander Galich]], and [[Alexander Solzhenitsyn|Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn]]. He was the only Soviet writer who officially congratulated [[Boris Pasternak]] on his having been awarded the [[Nobel Prize]] for [[literature]]. His daughter, [[Lydia Chukovskaya]], is remembered as a lifelong companion and secretary of the poet Anna Akhmatova, as well as an important writer herself. Chukovskaya's ''Sofia Petrovna'' was a courageous novella that was critical of the [[Stalinism|Stalinist]] [[Great Purges]], written during the time of [[Joseph Stalin|Stalin]]. | ||

| − | Chukovsky, too, did not escape scrutiny. His writings for children | + | Chukovsky, too, did not escape scrutiny. His writings for children endured severe criticism. [[Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya|Nadezhda Krupskaya]], wife of the leader of the [[Russian Revolution of 1917|Bolshevik Revolution]] and first Party Chairman of the Russian Communist Party, was an initiator of this campaign, but criticism also came also from [[Children's literature|children's writer]] [[Agniya Barto]], a patriotic writer who wrote anti-Nazi poetry during [[World War II]], often directly addressed to Stalin. |

| − | For his works on the life of Nekrasov he was awarded a [[Doktor Nauk|Doctor of Science degree]] in philology. He also received the [[Lenin Prize]] in 1962 for his book, ''Mastery of Nekrasov'' and an [[honorary doctorate]] from [[Oxford University]] in 1962. | + | For his works on the life of Nekrasov he was awarded a [[Doktor Nauk|Doctor of Science degree]] in [[philology]]. He also received the [[Lenin Prize]] in 1962, for his book, ''Mastery of Nekrasov'' and an [[honorary doctorate]] from [[Oxford University]] in 1962. |

===Sinyavsky-Daniel Trial=== | ===Sinyavsky-Daniel Trial=== | ||

| − | ' | + | In the mid-1960s, after the [[Khrushchev Thaw]] was reversed by the [[Leonid Brezhnev|Brezhnev]] regime's crackdown, two authors were arrested and tried for anti-Soviet activities. The Sinyavsky-Daniel trial ({{lang-ru|процесс Синявского и Даниэля}}) became a ''cause celèbre''. Russian writers [[Andrei Sinyavsky]] and [[Yuli Daniel]] were tried in the [[Moscow]] Supreme court, between autumn 1965 and February 1966, presided over by [[L.P. Smirnov]]. The writers were accused of having published anti-Soviet material in foreign editorials using the [[pseudonym]]s '''Abram Terz''' or Абрам Терц (Sinyavsky) and '''Nikolay Arzhak''' or Николай Аржак (Daniel). The court sentenced the writers to 5 and 7 years of forced labor. |

| − | [[pseudonym]]s '''Abram Terz''' or Абрам Терц (Sinyavsky) and '''Nikolay Arzhak''' or Николай Аржак (Daniel). The court sentenced the writers to 5 and 7 years of forced | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | The affair was accompanied by harsh [[propaganda]] campaign in the media. A group of Soviet luminaries sent a letter to Brezhnev asking that he not rehabilitate [[Stalinism]]. Chukovsky, already in his 70s, was among the distinguished signatories, which also included academicians [[Andrei Sakharov]], [[Igor Tamm]], [[Lev Artsimovich]], [[Pyotr Kapitsa]], [[Ivan Maysky]], the writer [[Konstantin Paustovsky]], actors [[Innokenty Smoktunovsky]], [[Maya Plisetskaya]], [[Oleg Yefremov]], directors [[Georgy Tovstonogov]], [[Mikhail Romm]], and [[Marlen Khutsiyev]], among others. | |

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * Brown, Edward J. | + | * Brown, Edward J. ''Russian Literature Since the Revolution.'' Harvard University Press, 1982. ISBN 0674782046. |

| − | * Terras, Victor | + | * Brown, Edward J. ''Major Soviet Writers: Essays in Criticism.'' Oxford University Press, 1973. ISBN 978-0195016840. |

| − | + | * Terras, Victor. ''A History of Russian Literature.'' Yale University Press, 1991. ISBN 0300059345. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[category:Art, music, literature, sports and leisure]] | [[category:Art, music, literature, sports and leisure]] | ||

Latest revision as of 14:50, 24 April 2018

| |

| Born: | April 31 1882 |

|---|---|

| Died: | 28 October 1969 (aged 87) |

Korney Ivanovich Chukovsky (Russian: Корней Иванович Чуковский, March 31, 1882 - October 28, 1969) was one of the most popular children's poets in the Russian language. His poems, "Doctor Aybolit" (Айболит), The Giant Roach (Тараканище), The Crocodile (Крокодил), and Wash'em'clean (Мойдодыр) have been favorites with many generations of Russophone children. He also was an influential literary critic and essayist.

Chukovsky survived the imposition of Socialist realism at the 1934 Writers' Congress and the Stalinization of literary and cultural life. Later, after the end of the Krushchev Thaw and Brezhnev retrenchment, Chukovsky worked on behalf of some of the writers who were attacked by the government. He joined Andrei Sakharov and others in signing a letter on the behalf of Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel after their arrest and conviction.

Early life

Nikolay Vasilyevich Korneychukov (Russian: Николай Васильевич Корнейчуков) was born in St. Petersburg. He reworked his original name into his now familiar pen-name while working as a journalist at Odessa News in 1901. Chukovksy was the illegitimate son of Ekaterina Osipovna Korneychukova, a peasant girl from the Poltava region of Ukraine, and Emmanuil Solomonovich Levinson, a man from a wealthy Jewish family. (His legitimate grandson was mathematician Vladimir Abramovich Rokhlin). Levinson's family did not permit his marriage to Korneychukova, and they eventually separated. Korneychukova moved to Odessa with Nikolay and his sibling. Levinson supported them financially for some time until his marriage to another woman. Nikolay studied at the Odessa gymnasium, where one of his classmates was Vladimir Zeev Jabotinsky. Later, Nikolay was expelled from the gymnasium for his "low origin" (an euphemism for illegitimacy). He had to get his secondary school and university diplomas by correspondence.

He taught himself English, and, in 1903-05, he served as the London correspondent at an Odessa newspaper, although he spent most of his time at the British Library instead of the press gallery in the Parliament. Back in Russia, Chukovsky started translating English works, notably Walt Whitman, and published several analyses of contemporary European authors, which brought him in touch with leading personalities of Russian literature and secured the friendship of noted Symbolist poet,Alexander Blok. His influence on Russian literary society of the 1890s is immortalized by satirical verses of Sasha Cherny, including Korney Belinsky (an allusion to the famous nineteenth century literary and social critic, Vissarion Belinsky). Later, he published several notable literary titles including From Chekhov to Our Days (1908), Critique Stories (1911), and Faces and Masks (1914). He also published a satirical magazine called Signal (1905-1906) and was arrested for "insulting the ruling house," but was acquitted after six months.

Later life

It was during that period that Chukovsky produced his first fantasies for children. Chukovsky's verses helped to revolutionize the way that children's poetry was written; "their clockwork rhythms and air of mischief and lightness in effect dispelled the plodding stodginess that had characterized pre-revolutionary children's poetry." Subsequently, they were adapted for theater and animated films, with Chukovsky as one of the collaborators. Sergei Prokofiev and other composers even adapted some of his poems for opera and ballet. His works were popular with emigre children as well, as Vladimir Nabokov's complimentary letter to Chukovsky attests.

In addition to his children's verses, Chukovsky was an important critic, translator and editor. During the Soviet period, Chukovsky edited the complete works of nineteenth century poet and journalist, Nikolay Nekrasov, who together with Belinski edited Sovremennik. He also published From Two to Five (1933), (first published under the title Small Children), a popular guidebook to the language of children. It was translated into many languages and printed in numerous editions. Chukovsky was also a member of the group of writers associated with the movement known as Factography.

Factography

Factography was associated with the Left Front of the Arts (Levyi Front Iskusstv—Левый фронт искусств), a widely ranging association of avant-garde writers, photographers, critics and designers in the Soviet Union, and their journal, LEF (ЛЕФ). It had two runs, one from 1923 to 1925, as LEF, and later from 1927 to 1929, as Novyi LEF (New LEF). The journal's objective, as set out in one of its first issues, was to "re-examine the ideology and practices of so-called leftist art, and to abandon individualism to increase art's value for developing communism."

The later New LEF, which was edited by Mayakovsky along with the playwright, screenplay writer and photographer Sergei Tretyakov, tried to popularize the idea of "Factography:" The idea that new technologies such as photography and film should be utilized by the working class for the production of "factographic" works. Chukovsky was one of its practitioners, along with Formalist critics Viktor Shklovsky and Yuri Tynyanov and poets Boris Pasternak, Vladimir Mayakovsky, and Osip Mandelshtam.

Starting in the 1930s, Chukovsky lived in the writers' village of Peredelkino near Moscow, where he is now buried.

Works

Wash'em'clean

Moidodyr (1923) is a poem for children by Korney Chukovsky about a magical creature by the same name. The name may be translated as "Wash'em'clean."

The poem is about a small boy who does not want to wash. He gets so dirty that all his toys, clothes and other possessions decide to magically leave him. Suddenly, from the boy's mother's bedroom appears Moidodyr—an anthropomorphic washstand. He claims to have powers over all washstands, soap bars and sponges. He scolds the boy and calls his soap bars and sponges to wash him. The boy tries to run away, chased by a vicious sponge. The chase is described as happening on St. Petersburg streets. Finally they meet another recurring character from Chukovsky's books—the Crocodile. The Crocodile swallows the sponge and becomes angry with the boy for being so dirty. Scared by the Crocodile, the boy goes back to Moidodyr and takes a bath. The poem ends with a moralistic note to children on the virtue of hygiene.

Moidodyr character became a symbol of clearness in Russia and is often used to advertise detergents and other products.

Ow, it hurts!

Doctor Aybolit (Russian: Доктор Айболит, Aibolit) is a fictional character from the Aybolit (Doctor Aybolit) poem for children by Korney Chukovsky, that was followed by several more books by the same author. The name may be translated as "Ow, it hurts!"

The origins of Aybolit can be traced to Doctor Dolittle by Hugh Lofting. Like Buratino by Aleksey Tolstoy or The Wizard of the Emerald City by Alexander Volkov, Aybolit is a loose adaptation of a foreign book by a Russian author. For example, the adaptation includes a Pushmi-pullyu, тяни-толкай (tyani-tolkay) in Russian.

A living prototype of the character may have been Chukovskys acquaintance, Vilnian Jewish doctor Zemach Shabad (1864-1935), to whom a monument was uncovered in Vilnius on May 16, 2007.

The character has become a recognizable feature of Russian culture. There are films based on Doctor Aybolit (Doktor Aybolit (black and white, 1938), Aybolit 66 (Mosfilm, 1967, English title: Oh How It Hurts 66), Doctor Aybolit (animated film, Kievnauchfilm, 1985)). His appearance and name are used in names, logos, and slogans of various medical establishments, candies, and so on.

Aybolit's antagonist, an evil robber Barmaley, became an archetypal villain in Russian culture. Actually, Barmaley debuted in Chukovsky's book Crocodile in 1916, 13 years before the first appearance of Aybolit.

The poem is a source a number of Russian catch phrases, such as "Nu spasibo tebe, Aybolit" ("Thanks to you, Aybolit"), "Ne hodite deti v Afriku gulyat" ("Children, don't go to Africa for a walk"). It was also the inspiration for the Barmaley Fountain in Stalingrad.

Legacy

As his invaluable diaries attest, Chukovsky used his popularity to help the authors persecuted by the regime including Anna Akhmatova, Mikhail Zoshchenko, Alexander Galich, and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. He was the only Soviet writer who officially congratulated Boris Pasternak on his having been awarded the Nobel Prize for literature. His daughter, Lydia Chukovskaya, is remembered as a lifelong companion and secretary of the poet Anna Akhmatova, as well as an important writer herself. Chukovskaya's Sofia Petrovna was a courageous novella that was critical of the Stalinist Great Purges, written during the time of Stalin.

Chukovsky, too, did not escape scrutiny. His writings for children endured severe criticism. Nadezhda Krupskaya, wife of the leader of the Bolshevik Revolution and first Party Chairman of the Russian Communist Party, was an initiator of this campaign, but criticism also came also from children's writer Agniya Barto, a patriotic writer who wrote anti-Nazi poetry during World War II, often directly addressed to Stalin.

For his works on the life of Nekrasov he was awarded a Doctor of Science degree in philology. He also received the Lenin Prize in 1962, for his book, Mastery of Nekrasov and an honorary doctorate from Oxford University in 1962.

Sinyavsky-Daniel Trial

In the mid-1960s, after the Khrushchev Thaw was reversed by the Brezhnev regime's crackdown, two authors were arrested and tried for anti-Soviet activities. The Sinyavsky-Daniel trial (Russian: процесс Синявского и Даниэля) became a cause celèbre. Russian writers Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel were tried in the Moscow Supreme court, between autumn 1965 and February 1966, presided over by L.P. Smirnov. The writers were accused of having published anti-Soviet material in foreign editorials using the pseudonyms Abram Terz or Абрам Терц (Sinyavsky) and Nikolay Arzhak or Николай Аржак (Daniel). The court sentenced the writers to 5 and 7 years of forced labor.

The affair was accompanied by harsh propaganda campaign in the media. A group of Soviet luminaries sent a letter to Brezhnev asking that he not rehabilitate Stalinism. Chukovsky, already in his 70s, was among the distinguished signatories, which also included academicians Andrei Sakharov, Igor Tamm, Lev Artsimovich, Pyotr Kapitsa, Ivan Maysky, the writer Konstantin Paustovsky, actors Innokenty Smoktunovsky, Maya Plisetskaya, Oleg Yefremov, directors Georgy Tovstonogov, Mikhail Romm, and Marlen Khutsiyev, among others.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brown, Edward J. Russian Literature Since the Revolution. Harvard University Press, 1982. ISBN 0674782046.

- Brown, Edward J. Major Soviet Writers: Essays in Criticism. Oxford University Press, 1973. ISBN 978-0195016840.

- Terras, Victor. A History of Russian Literature. Yale University Press, 1991. ISBN 0300059345.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Korney_Chukovsky history

- Moidodyr history

- Doctor_Aybolit history

- Agniya_Barto history

- LEF_(Journal) history

- Sinyavksy-Daniel_trial history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.