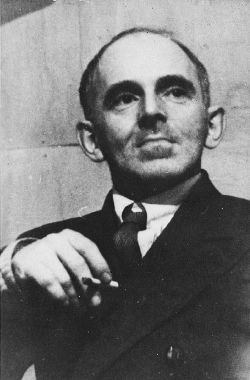

Osip Mandelshtam

| |

| Born: | January 15 [O.S. January 3] 1891 Warsaw, Congress Poland |

|---|---|

| Died: | December 27, 1938 transit camp "Vtoraya Rechka" (near Vladivostok), Soviet Union |

| Occupation(s): | poet, essayist, political prisoner |

| Literary movement: | Acmeist poetry |

Osip Emilyevich Mandelshtam (also spelled Mandelstam) (Russian: О́сип Эми́льевич Мандельшта́м) (January 15 [O.S. January 3] 1891 – December 27, 1938) was a Russian poet and essayist, one of the foremost members of the Acmeist school of poets. Acmeism, or the Guild of Poets, was a transient poetic school which emerged in 1910 in Russia under the leadership of Nikolai Gumilyov and Sergei Gorodetsky. The term was coined after the Greek word acme, i.e., "the best age of man." The Acmeist mood was first announced by Mikhail Kuzmin in his 1910 essay "Concerning Beautiful Clarity." The Acmeists contrasted the ideal of Apollonian clarity (hence the name of their journal, Apollo) to "Dionysian frenzy" propagated by the Russian Symbolist poets like Bely and Ivanov. To the Symbolists' preoccupation with "intimations through symbols" they preferred "direct expression though images".[1]

In his later manifesto "The Morning of Acmeism" (1913), Mandelshtam defined the movement as "a yearning for world culture." As a "neo-classical form of modernism" which essentialized "poetic craft and cultural continuity"[2], the Guild of Poets placed Alexander Pope, Theophile Gautier, Rudyard Kipling, Innokentiy Annensky, and the Parnassian poets among their predecessors. Major poets in this school include Gumilyov, Anna Akhmatova, Kuzmin, Mandelshtam, and Georgiy Ivanov. The group originally met in The Stray Dog Cafe in Saint Petersburg, then a celebrated meeting place for artists and writers. Mandelshtam's collection of poems Stone (1912) is considered the movement's finest accomplishment.

Life and work

Mandelshtam was born in Warsaw, to a wealthy Jewish family. His father, a tanner by trade, was able to receive a dispensation freeing the family from the pale of settlement, and soon after Osip's birth they moved to Saint Petersburg. In 1900 Mandelshtam entered the prestigious Tenishevsky school, which also counts Vladimir Nabokov and other significant figures of Russian (and Soviet) culture among its alumni. His first poems were printed in the school's almanac in 1907.

In April 1908 Mandelstam decided to enter the Sorbonne to study literature and philosophy, but he left the following year to attend the University of Heidelberg, and in 1911 for the University of Saint Petersburg. He never finished any formal post-secondary education. The year 1911 is also the year of Mandelstam's conversion to Christianity.

Mandelstam's poetry, acutely populist in spirit after the first Russian revolution, became closely associated with symbolist imagery, and in 1911 he and several other young Russian poets formed "Poets' Guild" (Russian: Цех Поэтов, Tsekh Poetov), under the formal leadership of Nikolai Gumilyov and Sergei Gorodetsky. The nucleus of this group would then become known as Acmeists. Mandelstam had authored The Morning Of Acmeism (1913, published in 1919), the manifesto for the new movement. 1913 also saw the publication of the first collection of poems, The Stone (Russian: Камень, Kamyen), to be reissued in 1916 in a greatly expanded format, but under the same title.

In 1922 Mandelstam arrived in Moscow with his newlywed wife, Nadezhda. At the same time his second book of poems, Tristia, was published in Berlin. For several years after that, he almost completely abandoned poetry, concentrating on essays, literary criticism, memoirs (The Din Of Time, Russian: Шум времени, Shum vremeni; Феодосия, Feodosiya - both 1925) and small-format prose (The Egyptian Stamp, Russian: Египетская марка, Yegipetskaya marka - 1928). To support himself, he worked as a translator (19 books in 6 years), then as a correspondent for a newspaper.

Stalin Epigram

Mandelstam's non-conformist, anti-establishment tendencies always simmered not far from the surface, and in the autumn of 1933 these tendencies broke through in form of the famous Stalin Epigram:

We live, but we do not feel the land beneath us,

Ten steps away and our words cannot be heard,

And when there are just enough people for half a dialogue,

Then they remember the Kremlin mountaineer.

His fat fingers are slimy like slugs,

And his words are absolute, like grocers' weights.

His cockroach whiskers are laughing,

And his boot tops shine.

And around him the rabble of narrow-neched chiefs –

He plays with the services of half-men.

Who warble, or miaow, or moan.

He alone pushes and prods.

Decree after decree he hammers them out like horseshoes,

In the groin, in the forehead, in the brows, or in the eye.

When he has an execution it's a special treat,

And the Ossetian chest swells.

The poem, sharply criticizing the "Kremlin highlander," was described elsewhere as a "sixteen line death sentence," likely prompted by Mandelshtam's personal observation in the summer of that year, while vacationing in Crimea, the effects of the Great Famine, a result of Stalin's collectivization in the USSR and his drive to exterminate the "kulaks." Six months later Mandelshtam was arrested.

However, after the customary pro forma inquest he not only was spared his life, but the sentence did not even include labor camps—a miraculous occurrence, usually explained by historians as due to Stalin's personal interest in his fate. Mandelshtam was "only" exiled to Cherdyn in the Northern Urals with his wife. After an attempt to commit suicide his regime was softened. While still banished from the largest cities, he was otherwise allowed to choose his new place of residence. He and his wife chose Voronezh.

This proved a temporary reprieve. In the coming years, Mandelstam would (as was expected of him) write several poems which seemed to glorify Stalin (including Ode To Stalin), but in 1937, at the outset of the Great Purges, the literary establishment began the systematic assault on him in print, first locally and soon after that from Moscow, accusing him of harboring anti-Soviet views. Early the following year Mandelshtam and his wife received a government voucher for a vacation not far from Moscow; upon their arrival he was promptly arrested again.

Four months later Mandelstam was sentenced to hard labor. He arrived at transit camp near Vladivostok. He managed to pass on a note to his wife back home with a request for warm clothes; he never received them. The official cause of his death is an unspecified illness.

Mandelstam's own prophecy was fulfilled:

"Only in Russia poetry is respected – it gets people killed. Is there anywhere else where poetry is so common a motive for murder?" [3]

Nadezhda Mandelshtam

Nadezhda Yakovlevna Mandelstam (Russian: Надежда Яковлевна Мандельштам, née Hazin; October 18, 1899 — December 29, 1980) was a writer in her own right. Born in Saratov into a middle-class Jewish family, she spent her early years in Kiev. After the gymnasium she studied art.

After their marriage in 1921, Nadezhda and Osip Mandelstam lived in Ukraine, Petrograd, Moscow, and Georgia. When Osip was arrested in 1934 for his Stalin epigram she travelled with him to Cherdyn and later to Voronezh.

After Osip Mandelstam's second arrest and his subsequent death at a transit camp "Vtoraya Rechka" near Vladivostok in 1938, Nadezhda Mandelstam led almost nomadic way of life, dodging her expected arrest and frequently changing places of residence and temporary jobs. On at least one occasion, in Kalinin, the NKVD (precursor to the KGB) came for her the next day after she fled.

As her mission in life, she determined to preserve and publish her husband's poetic heritage. She managed to keep most of it memorized because she didn't trust paper.

After the death of Stalin, Nadezhda Mandelstam completed her dissertation (1956) and was allowed to return to Moscow (1958).

In her memoirs, first published in the West, she gives an epic analysis of her life and criticizes the moral and cultural degradation of the Soviet Union of the 1920s and after.

In 1979 she gave her archives to Princeton University. Nadezhda Mandelstam died in 1980 in Moscow, aged 81.

Osip's selected works

- Kamen – Stone, 1913

- Tristia, 1922

- Shum vremeni – The Din Of Time, 1925 – The Prose of Osip Mandelstam

- Stikhotvoreniya 1921 – 1925 – Poems, publ. 1928

- Stikhotvoreniya, 1928

- O poesii – On Poetry, 1928

- Egipetskaya marka 1928 – The Egyptian Stamp

- Chetvertaya proza, 1930 – The Forth Prose

- Moskovskiye tetradi, 1930 – 1934 – Moskow Notebooks

- Puteshestviye v Armeniyu, 1933 – Journey to Armenia

- Razgovor o Dante, 1933 – Conversation about Dante

- Vorovezhskiye tetradi – Voronezh Notebooks, publ. 1980 (ed. by V. Shveitser)

Notes

- ↑ Mark Willhardt, and Alan Michael Parker. Who's Who in 20th Century World Poetry. (ondon: Routledge, 2001. ISBN 0415163552), 8.

- ↑ Michael Wachtel. The Cambridge Introduction to Russian Poetry. (Cambridge University Press, 2004. ISBN 0521004934), 8.

- ↑ Nadezhda Mandelstam presented her account of the events surrounding her husband's life in Hope against Hope ISBN 1860466354 and later continued with Hope Abandoned ISBN 0890549.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Nadezhda's Memoirs

- Hope against Hope (ISBN 1860466354) (wordplay: nadezhda means "hope" in Russian)

- Hope Abandoned (ISBN 0689105495)

- Wachtel, Michael, The Cambridge Introduction to Russian Poetry. Cambridge University Press, 2004. ISBN 0521004934

- Willhardt, Mark and Alan Michael Parker. Who's Who in 20th Century World Poetry. Routledge, 2001. ISBN 0415163552.

Bibliography

- Coetzee, J.M. "Osip Mandelstam and the Stalin Ode," Representations, No. 35, Special Issue: Monumental Histories. (Summer, 1991), pp. 72–83

- Davie, Donald: "In the Stopping Train." Carcanet (Manchester), 1977.

- Dutli R. Meine Zeit, mein Tier. Ossip Mandelstam. Eine Biographie. Zürich, 2003.

- Mandelstam, Osip: "Poems," chosen and translated by James Greene. Elek Books, 1977; revised and enlarged edition, Granada/Elek, 1980.

- Mandelstam, Osip: "Selected Poems," translated by David McDuff. Farrar, Strauss and Giroux (New York) and, with minor corrections, Rivers Press (Cambridge), 1973.

- Mandelstam, Osip: "50 Poems," translated by Bernard Meares with an Introductory Essay by Joseph Brodsky. Persea Books (New York), 1977.

- Mandelstam, Osip: "The Complete Poetry of Osip Emilevich Mandelstam," translated by Burton Raffel and Alla Burago. State University of New York Press (USA), 1973.

- Mandelstam, Osip: "Stone," translated by Robert Tracy. Princeton University Press (USA), 1981.

- Mandelstam, Osip: "Octets" 66-76, translated by Donald Davie, "Agenda," vol. 14, no. 2, 1976.

- Mandelstam, Osip: "The Goldfinch." Introduction and translations by Donald Rayfield. The Menard Press, 1973.

- Mandelstam, Osip: The Noise of Time: Selected Prose (European Classics) (Paperback), translated by Clarence Brown.

- Nilsson N. A. Osip Mandel’štam: Five Poems. Stockholm, 1974. Northwestern University Press; Reprint edition, 2002. ISBN 0-8101-1928-5

- Riley, John: "The Collected Works." Grossteste (Derbyshire), 1980.

- Ronen O. An Аpproach to Mandelstam. Jerusalem, 1983..

External links

All links retrieved November 17, 2022.

- 24 Poems by Mandelstam, translated by A. S. Kline

- 44 More Poems by Mandelstam, translated by A. S. Kline

- Osip Mandelstam. Tristia (tranlsation by Ilya Shambat)

- Poet Page: Osip Emelievich Mandelshtam

- by Osip Mandelstam Stalin Epigram translated by Darran Anderson

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.