Difference between revisions of "Israelites" - New World Encyclopedia

m |

|||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

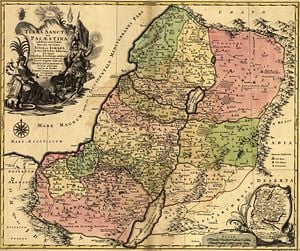

[[Image:1759_map_Holy_Land_and_12_Tribes.jpg|thumb|300px|1759 map of the tribal allotments of Israel]] | [[Image:1759_map_Holy_Land_and_12_Tribes.jpg|thumb|300px|1759 map of the tribal allotments of Israel]] | ||

| − | The final chapters of the [[Book of Numbers]] and the entire [[Book of Joshua]] describe the initial conquest of [[Canaan]] by the Israelites under the leadership first of [[Moses]], and then [[Joshua]]. The Book of Judges describes the Israelites' struggle to establish a national foundation as they face military opposition from the native peoples, temptation from Canaanite religious practices, and war among themselves. The prophet Samuel emerges at the end of the period of judges and creates a sense of national unity, anointing the Benjaminite Saul as the first king of "Israel." Soon, however, God rejects Saul and Samuel anoints David, who leads a band Judahite outlaws that ally themselves with the Philistines until Saul's death. Through a long civil war with Saul's son, Ish-bosheth, David eventually becomes king of | + | The final chapters of the [[Book of Numbers]] and the entire [[Book of Joshua]] describe the initial conquest of [[Canaan]] by the Israelites under the leadership first of [[Moses]], and then [[Joshua]]. The Book of Judges describes the Israelites' struggle to establish a national foundation as they face military opposition from the native peoples, temptation from Canaanite religious practices, and war among themselves. The prophet [[Samuel]] emerges at the end of the period of judges and creates a sense of national unity, anointing the Benjaminite [[Saul]] as the first king of "Israel." Soon, however, God rejects Saul, and Samuel anoints [[David]], who leads a band Judahite outlaws that ally themselves with the [[Philistines]] until Saul's death. Through a long civil war with Saul's son, [[Ish-bosheth]], David eventually becomes the second king of Israel, although he faces several rebellions in which the northern tribes and even elements of Judah reject his leadership. David's son [[Solomon]] succeeds in creating a more truly united kingship, although the northern tribes bristle under heavy taxation and forced labor for building projects in his capital of [[Jerusalem]]. After Solomon's death, a labor dispute occasions the loss of the ten northern tribes by his son [[Rehoboam]]. Thereafter, the nothern tribes are known as "Israel" while the southern kingdom is known as "Judah." A religious dispute between the two kingdoms centers on the question of whether all Israelites must worship in the Temple of Jerusalem, or whether northern tribes can make their offerings and pilgrimages a northern shrines and local high places. |

| − | [[Kingdom of Judah|Judah]]l was populated by the | + | [[Kingdom of Judah|Judah]]l was populated by the tribe of Judah, most of Benjamin, some of Levi (who acted as priests and guardians at the [[Solomon's Temple|Temple of Jerusalem]]) and also remnants of the Simeon, most of whom probably were assimilitaed into Judah early on. The northern kingdom was the more prosperous and powerful of the two, but the southern kingdom—according to the biblical writers—possessed a stronger sense of spiritual devotion to Yahweh. |

| − | In 722 B.C.E. the [[Assyrian people|Assyrians]] under [[Shalmaneser V]] conquered the northern [[Kingdom of Israel]], destroyed its capital of [[Samaria]] and sent the northern Israelites into exile and captivity. The so-called [[Ten Lost Tribes]] are those who were deported. In Jewish popular culture, the ten tribes disappeared from history, leaving only the tribes of [[Tribe of Benjamin|Benjamin]] and [[Tribe of Judah|Judah]] and the [[Tribe of Levi|Levi]] | + | In 722 B.C.E. the [[Assyrian people|Assyrians]] under [[Shalmaneser V]] conquered the northern [[Kingdom of Israel]], destroyed its capital of [[Samaria]] and sent the northern Israelites into exile and captivity. The so-called [[Ten Lost Tribes]] are those who were deported. In Jewish popular culture, the ten tribes disappeared from history, leaving only the tribes of [[Tribe of Benjamin|Benjamin]] and [[Tribe of Judah|Judah]] and the [[Tribe of Levi|Levi]] to eventually become the modern day Jews. |

=== Babylonian captivity and after=== | === Babylonian captivity and after=== | ||

| − | In 607 B.C.E. the | + | In 607 B.C.E. the [[kingdom of Judah]] was conquered by [[Babylon]], and leading Judeans were deported to Babylon and its environs in several stages. Some 70 years later, the [[Cyrus the Great]] of [[Persia]], who had recently conquered Babylon, allowed Jews to return to [[Jerusalem]] in 537 B.C.E. and rebuild the [[Temple in Jerusalem|Temple]]. By the end of this era, members of the Judean tribes, with the exception of the Levite priests, seem to have abandoned their individual identities in favor of a common one and were henceforth known as Jews. |

While Jewish history refers to the norther tribes as "lost" after this, the northern tribes, who had largely intermarried with people brought in by Assyria, were reconstituted as the nation of Samaria. Disdained by Jews because of their mixed lineage, they refused to worship in the rebuilt Temple of Jerusalem, believe that God had commanded the Israelites to establish a central sancturay at Mount Gerizim in the north. Samaria continued to exist as Judah/Judea's rival for several centuries, and its people were known as [[Samaritans]]. Suffering persecution under Rome, then under the Christian empires, and finally by Muslim rulers, the Samaritans nearly died out. Today a small population of Samaritans, with its priesthood and sacrificial traditions still intact, continues to exist in Israel and Palestine. | While Jewish history refers to the norther tribes as "lost" after this, the northern tribes, who had largely intermarried with people brought in by Assyria, were reconstituted as the nation of Samaria. Disdained by Jews because of their mixed lineage, they refused to worship in the rebuilt Temple of Jerusalem, believe that God had commanded the Israelites to establish a central sancturay at Mount Gerizim in the north. Samaria continued to exist as Judah/Judea's rival for several centuries, and its people were known as [[Samaritans]]. Suffering persecution under Rome, then under the Christian empires, and finally by Muslim rulers, the Samaritans nearly died out. Today a small population of Samaritans, with its priesthood and sacrificial traditions still intact, continues to exist in Israel and Palestine. | ||

Revision as of 23:33, 1 May 2007

An Israelite is a member of the Twelve Tribes of Israel, descended from the twelve sons of the Biblical patriarch Jacob who was renamed Israel by God in the book of Genesis, 32:28. The Israelites were a group of Hebrews, as described in the Hebrew Bible. There are modern historical debates about the origins of the Hebrews/Israelites.

The English word Israelite derives from ישראל (Standard Yisraʾel Tiberian Yiśrāʾēl, "Upright (with) God"); see the article Israel for details on the word's definition.

Biblical origins

According to the Hebrew Bible, the Israelites were the descendants of the sons of Jacob, later known as Israel. His twelve male children were Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Judah, Issachar, Zebulun, Dan, Gad, Naphtali, Asher, Joseph, and Benjamin.

In the biblical narrative, the sons of Jacob all migrate to Egypt where one of them, Joseph, has become the prime minister. They remain there for 400 years, during which time they multiply to become the twelve "tribes of Israel." Together, they leave Egypt under the leadership of Moses, during the Exodus. The Tribe of Levit is set apart during this time as a priestly class to assist the sons of Aaron and attend the Tabernacle which the Israelites carried through the wilderness. After 40 years of wandering through the wilderness, the Israelites finally reach Canaan and conquer it. The Tribe of Joseph was divided into the two half-tribes of Benjamin and Manasseh and the Tribe of Levi, rather than possessing its own territory, served as a priestly group scattered among the other Israelite tribes.

Strictly speaking, therefore, there were actually 13 tribes, but 12 tribal areas. When the tribes are listed in reference to their receipt of land, as well as to their encampments during the 40 years of wandering in the desert, the Tribe of Joseph is replaced by the tribes of Ephraim and Manasseh, while the Tribe of Levi disappears from the list. Thus, the tribes are listed in the following ways:

|

Original division:

|

Division according to apportionment of land in Israel:

|

Israelite tribes in of Canaan

The final chapters of the Book of Numbers and the entire Book of Joshua describe the initial conquest of Canaan by the Israelites under the leadership first of Moses, and then Joshua. The Book of Judges describes the Israelites' struggle to establish a national foundation as they face military opposition from the native peoples, temptation from Canaanite religious practices, and war among themselves. The prophet Samuel emerges at the end of the period of judges and creates a sense of national unity, anointing the Benjaminite Saul as the first king of "Israel." Soon, however, God rejects Saul, and Samuel anoints David, who leads a band Judahite outlaws that ally themselves with the Philistines until Saul's death. Through a long civil war with Saul's son, Ish-bosheth, David eventually becomes the second king of Israel, although he faces several rebellions in which the northern tribes and even elements of Judah reject his leadership. David's son Solomon succeeds in creating a more truly united kingship, although the northern tribes bristle under heavy taxation and forced labor for building projects in his capital of Jerusalem. After Solomon's death, a labor dispute occasions the loss of the ten northern tribes by his son Rehoboam. Thereafter, the nothern tribes are known as "Israel" while the southern kingdom is known as "Judah." A religious dispute between the two kingdoms centers on the question of whether all Israelites must worship in the Temple of Jerusalem, or whether northern tribes can make their offerings and pilgrimages a northern shrines and local high places.

Judahl was populated by the tribe of Judah, most of Benjamin, some of Levi (who acted as priests and guardians at the Temple of Jerusalem) and also remnants of the Simeon, most of whom probably were assimilitaed into Judah early on. The northern kingdom was the more prosperous and powerful of the two, but the southern kingdom—according to the biblical writers—possessed a stronger sense of spiritual devotion to Yahweh.

In 722 B.C.E. the Assyrians under Shalmaneser V conquered the northern Kingdom of Israel, destroyed its capital of Samaria and sent the northern Israelites into exile and captivity. The so-called Ten Lost Tribes are those who were deported. In Jewish popular culture, the ten tribes disappeared from history, leaving only the tribes of Benjamin and Judah and the Levi to eventually become the modern day Jews.

Babylonian captivity and after

In 607 B.C.E. the kingdom of Judah was conquered by Babylon, and leading Judeans were deported to Babylon and its environs in several stages. Some 70 years later, the Cyrus the Great of Persia, who had recently conquered Babylon, allowed Jews to return to Jerusalem in 537 B.C.E. and rebuild the Temple. By the end of this era, members of the Judean tribes, with the exception of the Levite priests, seem to have abandoned their individual identities in favor of a common one and were henceforth known as Jews.

While Jewish history refers to the norther tribes as "lost" after this, the northern tribes, who had largely intermarried with people brought in by Assyria, were reconstituted as the nation of Samaria. Disdained by Jews because of their mixed lineage, they refused to worship in the rebuilt Temple of Jerusalem, believe that God had commanded the Israelites to establish a central sancturay at Mount Gerizim in the north. Samaria continued to exist as Judah/Judea's rival for several centuries, and its people were known as Samaritans. Suffering persecution under Rome, then under the Christian empires, and finally by Muslim rulers, the Samaritans nearly died out. Today a small population of Samaritans, with its priesthood and sacrificial traditions still intact, continues to exist in Israel and Palestine.

The Jews, meanwhile were scattered after a rebellions against Rome 66 C.E. ended in the desruction of the Temple of Jerusalem and the expulsion of the Jews from the capital. A further rebellion in the second century under the messianic leader Bar Kochba led to a near complete diaspora in which Jews moved east to the cities of the Eastern Roman Empire, west to Alexandria and Africa, and north into Asia Minor and southern Europe, eventually making their way to northern and eastern Europe and the United States. The Jews of Europe face near annihlation in World War II when Adolf Hitler's Third Reich planned their complete extermination. Due to the victory of the Allies, however, they survived, and the state of Israel was established in 1948 as a have for holocaust survivors and other Jewish refugees.

Modern views

Archaeology and modern biblical criticism challenge the biblical view. Rather than migrating en masse together out of Egypt and conquering Canaan in a short period, a much more gradual process is envisioned. Moreover, many scholars believe that several, perhaps most, of the Israelite tribes never migrated to Egypt at all. The archaelogical record is missing any evidence of a large migration from Egypt to Canaan (said the Bible to include 600,000 men of fighting age or at least 2 million people in all), while even relatively small bands of migrants usually leave some evidence of their travels. Moreover, the supposed period of Israelite conquest shows little evidence of what is described in the Bible. Rather, it seems that Caananite and Israelite cultures were virtually indistinguishable during the period in question, and what appears to have occured was a process of gradual infilitration or assimilation of Israelite culture into Canaanite society.

In addition, the existence of a group known as "Israel" in Canaan is confirmed by a stele left by the Egyptian ruler Merneptah, (reigned 1213 to 1203 B.C.E.) who boasts of having devastated "Israel" and several other peoples in Canaan at a time when most scholars believe the Exodus had not yet occurred.

Accordingly, many of the so-called Israelites did not come from Egypt but must have lived in the area of Canaan and later joined the emerging Israelite federation at a later date. The process is hinted at the Book of Judges where the Israelite tribes appear as very distinct from one another and often live in peace with their Canaanite neighbors. That non-Israelite people federated with Israel in Canaan is confirmed in Judges 1, where the Kenites join Judah. Another example of "adoption" may be seen in the Perizzites, who are usually named as a Canaanite tribe against whom Israel must fight (Gen. 3:8 and 15:19, etc.), but in Num. 26:20 are identified as part of the lineage and tribe of Judah, through his son Perez. Meanwhile, the biblical story of the conquest of Canaan may represent the memories of Apiru victories written down several centuries after the fact and filtered through the religious viewpoint of that later time.

According to this theory, the late-comers were adopted in the "people of Israel" and in turn adopted the Israelite national origin stories in a similar manner to the way more recent American immigrants identify with the story of the British colonists coming to the new world in search of freedom and prosperity.

A number of theories have been put for regarding the identity of the Israelites and the process by which Israel became a nation. The tribe of Joseph (later Ephraim and Manasseh) is often identified as a group which did spend time in Egypt and later came to Canaan.[1] The "Israel" refered to in the Merneptah Stele may be the Bedouin-like wanderers known to elsewhere as Shasu who, according the archaelogical record were the first group leaving evidence of worship the Israelite GodYahweh.

Other groups that may have been known later as Israelites include the Hyksos and the Apiru. The Hyksos were a large population of Semitic people who for a time ruled Egypt but were driven north during the reign of Ahmose I in the sixteenth century B.C.E. The Apiru (also called Habiru) constituted groups of nomadic raiders who sometimes attacked and occasionally conquered Canaanite towns in the period roughly equivalent to the period of the Israelite conquest of Canaan up until the reign of King David. One theorgy holds that David himself was the last and greatest of the Apiru bandit leaders. (Finkelstein 2002)

Non-Jewish "Israelite" traditions

Some modern religions maintain that their followers are "Israelites" or "Jews" although the meaning of these claims differs widely. In some cases, the claim is spiritual, but in other cases groups believe themselves to be actual physical descendants of the Israelites. In addition there are a number of anti-Semitic groups who claim that they alone are the "true" Israelites, while the Jews are evil imposters.

Spiritual "Israelites"

The largest group claiming spiritual Israelite status is Christianity. This viewpoint is based New Testament teachings such as "Through the gospel the Gentiles are heirs together with Israel" (Ephesians 3:6) and "It is not the natural children who are God's children, but it is the children of the promise who are regarded as Abraham's offspring (Romans 9:8). Jesus himself is quoted in the Gospels as saying to the Jews who opposed him: "I tell you that the kingdom of God will be taken away from you and given to a people who will produce its fruit." (Matthew 21:43)

The Latter Day Saint movement (Mormons) believe that through baptism and receiving the Gift of the Holy Ghost, they become "regathered" Israelites.

Unificationists see Christianity as a "second Israel" while the Unification is a "third Israel." Thus, Reverend Sun Myung Moon once said:

- Judaism, centered upon the Old Testament, was the first work of God and is in an elder brother's position. Christianity, centered upon the New Testament, is in the position of the second brother. The Unification Church, through which God has given a new revelation, the Completed testament, is in the position of the youngest brother. ("America and God's Will" September 18, 1976 Washington DC)

Physical "Israelites"

Samaritans are a group claiming physical descent from the Israelites. Like the Jews, the Samaritans accept the five books of the Torah and the Book of Joshua, but they reject the later Jewish writers, as well as the later Israelite prophets, kings, and priesthood as illegimate. They regard themselves as the descendants primarily of the tribes of Ephraim and Mannasseh. Recent genetic surverys suggest that their claim to lineal descent from the Israelites may indeed be valid (see Samaritans).

Karaite Judaism includes people who once were accepted a regular Jews during the talmudic period rejected Judaism emerging tradition of Oral Law (the Mishnah and the Talmuds). There are approximately 50,000 adherents of Karaite Judaism, most of whom reside in Israel. Some communities of Karaites are also present in Eastern Europe.

Rastafarians believe that the black races are the true Children of Israel, or Israelites. A number of other black Israelite movements also exist. The African Hebrew Israelites of Jerusalem (known in Israel as the Black Hebrews) is a small spiritual group whose members believe they are descended from the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel. Most members live in their own community in Dimona, Israel.

A number of other groups claim to be the only "true Israelites" an condemn the Jews as imposters to that status.

See also

- Kingdom of Israel

- Kingdom of Judah

- History of ancient Israel and Judah

- Gentile

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Redford, Donald. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton University Press, 1992. ISBN 0-691-00086-7.

External links

- The Israelite census, of the book of numbers, in isolation, at wikisource

Template:Israelites Template:Credit:119143710

- ↑ In the biblical narrative Joseph's time in Egypt is told in detail, while the story of the migration of the other tribes to Egypt has the character of an addendum explaining how the Israelites all came to be in Egypt even though Jacob was known to be buried in Canaan.